Case Report Open Access

T-Cell/Histiocyte-Rich Large B-Cell Lymphoma Masquerading as Autoimmune Hepatitis with Clinical Features of Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis

Minesh Mehta1*, Jiang Wang2, Ross McHenry1 and Stephen Zucker1

1Division of Digestive Diseases and University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati OH 45267-0595, USA

2Department of Pathology, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati OH 45267-0595, USA

- *Corresponding Author:

- Minesh Mehta

Department of Internal Medicine

231 Albert Sabin Way, Cincinnati

OH 45267, USA

Tel: 706-248-9331

E-mail: mehtame@ucmail.uc.edu

Received date: March 14, 2015; Accepted date: April 16, 2015;Published date: April 28, 2015

Citation: Mehta M, Wang J, McHenry R, Zucker S (2015) T-Cell/Histiocyte-Rich Large B-Cell Lymphoma Masquerading as Autoimmune Hepatitis with Clinical Features of Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis. J Gastrointest Dig Syst 5:283. doi:10.4172/2161-069X.1000283

Copyright: ©2015 Mehta M, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Gastrointestinal & Digestive System

Abstract

We report the case of a 20-year-old male who presented with acute hepatitis resembling autoimmune hepatitis, but subsequently found to be T-Cell Rich/Histiocyte Rich Large B-Cell Lymphoma. Our patient was mistakenly diagnosed with autoimmune hepatitis based on liver histology demonstrating a pronounced lobular and portal infiltrate comprised predominately of polyclonal T cells, in the setting of negative serologic testing. This conclusion was reinforced by a compelling biochemical response to standard immunosuppressive therapy. The correct diagnosis of T/HRBCL subsequently was established by bone marrow biopsy (and confirmed by lymph node biopsy) when the patient presented with clinical features of HLH. In conclusion, our case elucidates a unique clinical spectrum of T/HRBCL. This patient initially presented with acute hepatitis, before mistakenly being diagnosed with autoimmune hepatitis and finally exhibited clinical features of HLH, which led to the diagnosis of T/HRBCL. It is critical to consider lymphoma in the differential for acute hepatopathy and clinical features of HLH.

Keywords

Autoimmune hepatitis; T-Cell/Histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma; Hemophagocytosis

Case Report

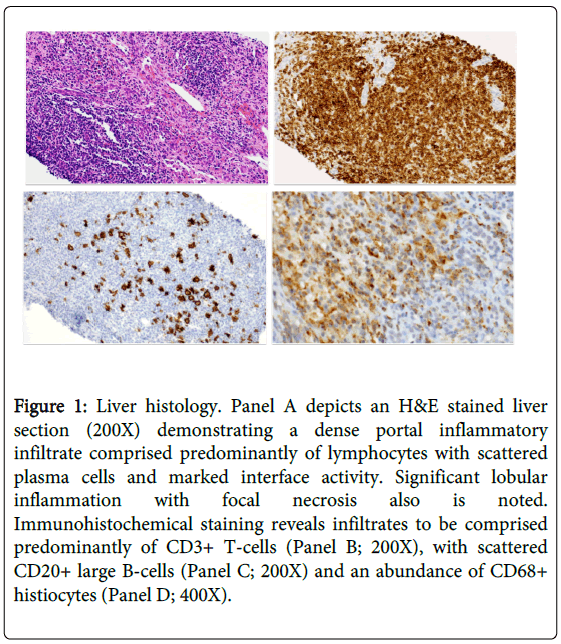

A 20-year-old man was seen for evaluation of abnormal liver tests. Six months previously, the patient presented to an outside facility with new onset jaundice and dark urine following a 2-week prodrome of malaise, fatigue, and abdominal discomfort. Serologic analysis was notable for ALT (alanine transaminase) 2338 U/L, AST (aspartate transaminate) 2129 U/L, alkaline phosphatase 267 U/L, total bilirubin 8.4 mg/dL, direct bilirubin 6.5 mg/dL, albumin 3.7 g/L, and INR 1.4. Testing for hepatitis A, B, C, EBV (Epstein-barr virus), and CMV (cytomegalovirus) was negative. His symptoms gradually abated over several weeks. At two months follow-up, the patient reported feeling well. Physical examination was notable for splenomegaly. Serologic testing revealed: ALT 197 U/L, AST 120 U/L, alkaline phosphatase 162 U/L, total bilirubin 1.7 mg/dL, albumin 4.2 g/L, INR 1.5, WBC (white blood cells) 4.4, hemoglobin 13.9, platelets 118. Serum ceruloplasmin, ANA, anti-smooth muscle antibody, total IgG, anti-LKM (liver-kidney-muscle) antibody, alpha-1-antitrypsin, iron saturation, and ferritin were normal. A subsequent transjugular liver biopsy demonstrated histologic findings that were consistent with autoimmune hepatitis (Figure 1). Oral prednisone 40 mg and azathioprine (2 mg/kg) daily were initiated, resulting in prompt biochemical improvement: ALT 40 U/L, AST 47 U/L, AP 127 U/L, total bilirubin 1.2 mg/dL, INR 1.2, WBC 4.4, hemoglobin 11.4, platelets 132.

Figure 1: Liver histology. Panel A depicts an H&E stained liver section (200X) demonstrating a dense portal inflammatory infiltrate comprised predominantly of lymphocytes with scattered plasma cells and marked interface activity. Significant lobular inflammation with focal necrosis also is noted. Immunohistochemical staining reveals infiltrates to be comprised predominantly of CD3+ T-cells (Panel B; 200X), with scattered CD20+ large B-cells (Panel C; 200X) and an abundance of CD68+ histiocytes (Panel D; 400X).

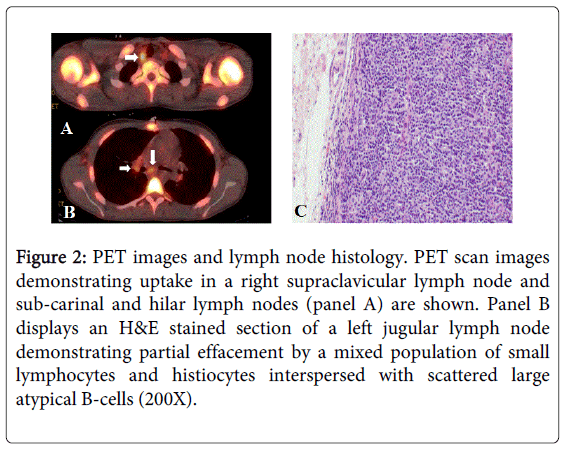

One month later, the patient presented with acute onset malaise, fatigue, fever (102°F), and pancytopenia: WBC 1.1, hemoglobin 8.5, platelets 56, ferritin 5290 ng/mL, TG 223. Soluble IL2 receptor (sIL-2R) level was markedly elevated at 31,000 U/mL. The diagnosis of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) was entertained. Bone marrow biopsy revealed a hypercellular marrow diffusely infiltrated by sheets of small lymphocytes that stained positive for CD3, CD5, CD7 and CD45 and were interspersed with scattered large atypical lymphocytes that were positive for CD20 and PAX-5 and negative for CD15, ALK-1, and CD30. The histologic findings were indicative of T-cell/Histiocyte rich large B-Cell lymphoma (T/HRBCL). A PET scan demonstrated diffuse lymph node uptake (Figure 2A), and the diagnosis was confirmed by jugular lymph node biopsy (Figure 2B). Retrospective immunohistochemical staining of the patient’s liver biopsy was consistent with T/HRBCL (Figure 1B-1D).

Figure 2: PET images and lymph node histology. PET scan images demonstrating uptake in a right supraclavicular lymph node and sub-carinal and hilar lymph nodes (panel A) are shown. Panel B displays an H&E stained section of a left jugular lymph node demonstrating partial effacement by a mixed population of small lymphocytes and histiocytes interspersed with scattered large atypical B-cells (200X).

Discussion

This patient was initially thought to have autoimmune hepatitis based on liver histology and a compelling biochemical response to immunosuppressive therapy. The correct diagnosis of T/HRBCL subsequently was established by bone marrow biopsy after the patient presented with clinical features of HLH, the diagnostic criteria for which include at least five of the following eight findings: fever >38.5°C, splenomegaly, peripheral blood cytopenia, hypertriglyceridemia and/or hypofibrinogenemia, hemophagocytosis (in bone marrow, spleen, lymph node, or liver), low or absent NK cell activity, ferritin >500 ng/mL, and elevated sIL-2R (also termed soluble CD25) [1]. Hematological malignancies, particularly non-Hodgkin lymphoma, are the most common underlying disease in adults who present with the hemophagocytic syndrome [2,3]. Moreover, the patient manifested a level of sIL-2R >5000 U/ml and an sIL-2R/ferritin ratio (>2.0) that have been strongly associated with lymphoma [4].

T/HRBCL is a rare subset of Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL). It occurs predominately in middle-aged men, and more commonly involves the liver, spleen, and bone marrow than does DLBCL [5-7]. Typical clinical manifestations of T/HRBCL include generalized fatigue, varying degrees of abnormal liver tests, and organomegaly [8-11]. T/HRBCL is characterized histologically by the presence of fewer than 10% neoplastic B cells interspersed within a robust inflammatory response comprised of small T-lymphocytes, with or without histiocytes [12]. Liver involvement is characterized by infiltration of the portal tracts with large numbers of small, reactive lymphocytes and histocytes, the confluence of which can lead to a “geographic map” appearance [9]. Because the T-cell infiltrate is polyclonal, interface activity is not uncommon, and the scattered neoplastic B cells are easily overlooked, the histologic features seen on liver biopsy can be difficult to distinguish from autoimmune hepatitis. Further confounding the diagnosis in our patient was the excellent biochemical response to immunosuppressive therapy. Khan et al. described eight cases of T/HRBCL presenting as liver disease, one of which was mistakenly diagnosed with “chronic active hepatitis” [11]. Notably, only a single patient in that series was suspected of having lymphoma on the basis of liver histology. In additional small series [10,13], liver disease initially was ascribed to acute hepatitis B, alcoholic hepatitis, choledocholithiasis, primary biliary cirrhosis, or granulomatous hepatitis. A number of these patients succumbed to their illness in short order, highlighting the critical importance of awareness of the diagnosis. Our patient presently remains in remission after receiving 6 cycles of rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisolone (RCHOP), along with intrathecal methotrexate.

References

- Henter JI, Horne A, Aricó M, Egeler RM, Filipovich AH, et al. (2007) HLH-2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer 48: 124-131.

- Riviere S, Galicier L, Coppo P, Marzac C, Aumont C, et al. (2014) Reactive hemophagocytic syndrome in adults: A multicenter retrospective analysis of 162 patients. Am J Med 2014.

- Takahashi N, Chubachi A, Kume M, Hatano Y, Komatsuda A, et al. (2001) A clinical analysis of 52 adult patients with hemophagocytic syndrome: the prognostic significance of the underlying diseases. Int J Hematol 74: 209-213.

- Tabata C, Tabata R (2012) Possible prediction of underlying lymphoma by high sIL-2R/ferritin ratio in hemophagocytic syndrome. Ann Hematol 91: 63-71.

- Achten R, Verhoef G, Vanuytsel L, De Wolf-Peeters C (2002) T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma: a distinct clinicopathologic entity. J Clin Oncol 20: 1269-1277.

- Bouabdallah R, Mounier N, Guettier C, Molina T, Ribrag V, et al. (2003) T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphomas and classical diffuse large B-cell lymphomas have similar outcome after chemotherapy: a matched-control analysis. J Clin Oncol 21: 1271-1277.

- Aki H, Tuzuner N, Ongoren S, Baslar Z, Soysal T, et al. (2004) T-cell-rich B-cell lymphoma: a clinicopathologic study of 21 cases and comparison with 43 cases of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Leuk Res 28: 229-236.

- Dargent JL, De Wolf-Peeters C (1998) Liver involvement by lymphoma: identification of a distinctive pattern of infiltration related to T-cell/histiocyte-rich B-cell lymphoma. Ann Diagn Pathol 2: 363-369.

- Harris AC, Ben-Ezra JM, Contos MJ, Kornstein MJ (1996) Malignant lymphoma can present as hepatobiliary disease. Cancer 78: 2011-2019.

- Castroagudin JF, Gonzalez-Quintela A, Fraga M, Forteza J, Barrio E (1999) Presentation of T-cell-rich B-cell lymphoma mimicking acute hepatitis. Hepatogastroenterology 46: 1710-1713.

- Khan SM, Cottrell BJ, Millward-Sadler GH, Wright DH (1993) T-cell-rich B-cell lymphoma presenting as liver disease. Histopathology 23: 217-224.

- Campo E, Swerdlow SH, Harris NL, Pileri S, Stein H, et al. (2011) The 2008 WHO classification of lymphoid neoplasms and beyond: evolving concepts and practical applications. Blood 117: 5019-5032.

- Harris AC, Kornstein MJ (1993) Malignant lymphoma imitating hepatitis. Cancer 71: 2639-2646.

Relevant Topics

- Constipation

- Digestive Enzymes

- Endoscopy

- Epigastric Pain

- Gall Bladder

- Gastric Cancer

- Gastrointestinal Bleeding

- Gastrointestinal Hormones

- Gastrointestinal Infections

- Gastrointestinal Inflammation

- Gastrointestinal Pathology

- Gastrointestinal Pharmacology

- Gastrointestinal Radiology

- Gastrointestinal Surgery

- Gastrointestinal Tuberculosis

- GIST Sarcoma

- Intestinal Blockage

- Pancreas

- Salivary Glands

- Stomach Bloating

- Stomach Cramps

- Stomach Disorders

- Stomach Ulcer

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 15292

- [From(publication date):

June-2015 - Sep 22, 2024] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 10858

- PDF downloads : 4434