In Vitro Oxidative Damage Induced in Livers, Hearts and Kidneys of Rats Treated with Leachate from Battery Recycling Site: Evidence for Environmental Contamination and Tissue Damage

Received: 24-Aug-2012 / Accepted Date: 27-Sep-2012 / Published Date: 01-Oct-2012 DOI: 10.4172/2161-0681.1000129

Abstract

Abstract

The health effects of the Municipal Auto-Battery Dust Leachate (MABDL) and Elewi Odo Municipal Auto-

Battery Recycling Site Leachate (EOMABRL) on levels of Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances (TBARS) were

investigated in livers, kidneys and hearts of male albino rat-in vitro. The two varieties of leachates significantly

(p<0.05) increased MDA level in the liver, kidney and heart in a dose-dependent manner with Municipal Auto-Battery

Dust Leachate (MABDL) having stronger induction ability than Elewi Odo Municipal Auto-Battery Recycling Site

Leachate (EOMABRL). MDA levels of EOMABRL were significantly (p<0.05) elevated in the liver, kidney and heart

by 55.56%, 41.3% and 39.13% respectively compared to the corresponding control at the highest dose. Similarly,

MDA contents of MABDL were significantly (p<0.05) elevated in the kidney, heart and liver by 195.65%, 115.2% and

83.33% respectively compared to the corresponding control at the highest dose. However, the liver is highly sensitive

to EOMABRL exposure than kidney and heart. In contrast, the kidney is more susceptible to MABDL exposure than

heart and liver. Collectively, the possible mechanisms by which varieties of battery leachates exert nephritis, hepatitis

and cardiovascular malfunctioning is through high induction of lipid peroxidation and heavy metal (Cu2+ ,Fe2+ ,Pb2+ etc)

catalyzed hydrogen peroxide decomposition to produced OH• via Fenton reaction.

Keywords: Livers; Kidneys; Hearts; Lipid peroxidation; Fenton reaction; EOMABRL- MABDL

308423Introduction

Environmental pollution from municipal landfill is a growing problem in many industrialised countries that are generating waste waters. Due to the enormous number of potentially polluting substances contained in such landfill/waters effluents, a chemicalspecific approach is insufficient to provide the information about water quality. Leachate from a landfill varies widely in composition depending on the age of the landfill and the type of waste that contains [1,2]. It can usually contain both dissolved and suspended material. Threats to the groundwater from the unlined and uncontrolled landfills exist in many parts of the world, particularly in the under-developed and developing countries where the hazardous industrial waste is also co-disposed with municipal waste and no provision to separate secured hazardous landfills exists. Even if there are no hazardous wastes placed in municipal landfills, the leachate is still reported as a significant threat to the groundwater [3]. A number of incidences have been reported in the past, where leachate had contaminated the surrounding soil and polluted the underlying ground water aquifer or nearby surface water [4-8], thereby making groundwater contaminated by leachates from municipal landfills as the most commonly human health and environmental hazards [9]. These leachates which percolate into underground water may affect vital organ’s functions when ingested via water drinking or during exposure at work place or recreation centres such as swimming pool centre. This may be as a result of the presence of heavy metals or many constituents of leachate that has the potential of initiating lipid peroxidation via free radical / reactive oxygen species formation.

Lipid peroxidation primarily occurs through a free radical chain reaction, and oxygen is the most important factor on the development of lipid peroxidation in tissues resulting in many pathological processes which lead to cancer, degenerative disease, and other diseases [10-12]. Theoretically, oxygen molecule and Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid (PUFA) cannot interact with each other because of thermodynamic constraints. Ground state oxygen does not have strong enough reactivity, but can be converted to Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) such as hydroxyl radical(_OH•), superoxide anion (O2-.), hydrogen peroxide(H2O2_), hydroperoxyl radical (HO2‑), lipid peroxyl radical (LOO‑), alkoxyl radical (LO‑), iron-oxygen complexes (ferryl- and perferryl radical) and singlet oxygen (O2), some of which are highly reactive to initiate lipid peroxidation. In addition, numerous agents such as enzymes and transition metals directly or indirectly catalyze these oxidative processes through enzymatic and non-enzymatic mechanisms. Especially, iron plays a critical role in lipid peroxidation process as a major catalyst [13-16]. However, it is essential to use biological test systems with living cells or organisms that give a global response to the pool of micropollutants and macropollutants present in the sample [17]. Present study, therefore, adopts the use of biochemical test to (a) Evaluate the toxicological effects of Municipal Battery-Dust Leachate (MABDL) and Elewi Odo Municipal Battery Recycling Site Leachate (EOMABRL) on the integrity of structural membrane of livers, kidneys and hearts of male albino rats via induction of lipid peroxidation.

(b) Suggest the tissue(s) that is (are) more susceptible to oxidative damage when treated with municipal battery-dust leachate.

Materials and Methods

Battery-dust leachate preparation (MABDL)

Eight different car batteries designated as (BL1, BL2, BL3, BL4, BL5, BL6, BL7 and BL8) were randomly purchased from different workshops of Ibadan metropolis, Southwest, Nigeria in which the wetdust of the batteries was isolated. The wet dust was air-dried, finely ground with pestle and mortar and sifted through a 63 micrometer (pore size) sieve to obtain a homogenous mixture. Then, the batterydust leachate (100%) was prepared from each battery homogenous mixture using whattman filter paper, an extraction procedure known as American Society for Testing and Material (ASTM) [18], with slight modification. The filtrate was subjected to the determination of heavy metal concentration using atomic absorption spectrophotometer [19].

Environmental auto-battery recycling site leachate preparation (EOMABRL)

Battery solid (decomposed) wastes were also collected and thoroughly mixed from different points on the battery `recycling site, located at Ibadan North, South West, Nigeria and were shredded to provide representative samples for simulation in the laboratory. 100% of the mixture was mixed thoroughly and allowed to stand for 48 hours at room temperature. Continuous stirring was done manually at regular interval of 2 hours. At 48 hour, solid and liquid portion was separated, and then the liquid portion was thoroughly mixed (18). The environmental samples were filtered to remove debris, the PH was measured and the leachates stored at 4°C until use. The environmental leachate was designated as Elewi Odo Municipal Auto-Battery Recycling Site Leachate (EOMABRL).

Hydrogen peroxide (H202) assays

The ability of battery-dust leachate (0-300 μl) to induce hydrogen peroxide assessed by the method of IIhami [20]. A solution of 40mM was prepared in phosphate buffer (pH 7.4).1.0 of sample was added to 0.6ml of hydrogen peroxide solution of 40 Mm. Absorbance of hydrogen peroxide at 230 nm was determined after 10 minutes against a blank solution containing phosphate buffer solution without hydrogen peroxide. Ascorbic acid was used as positive control. The percentage induction of hydrogen peroxide of the samples were calculated using the following equation: % induced [H2O2] = [(A1-Ao)/A0]*100. Where Ao was the absorbance of the control and A1 was the absorbance of the sample.

Lipid peroxidation assay

Preparation of tissue homogenates: Male rats were decapitated under mild diethyl ether anaesthesia and the livers, hearts and kidneys were rapidly isolated and placed on ice and weighed. Each of the tissues was subsequently homogenized in cold saline (1/10 w/v) with about 10-up-and-down strokes at approximately 1200 rev/min in a Teflon glass homogenizer. The homogenate was centrifuged for 10 mins at 3000xg to yield a pellet that was discarded, and a Low-Speed Supernatant (SI) was kept for lipid peroxidation assay.

Lipid peroxidation and thiobarbituric acid reactions: The lipid peroxidation assay was carried out using the modified method of Ohkawa et al. (21). 100 μl SI fraction was mixed with a reaction mixture containing 30 μl of 0.1 M PH7.4 Tris-HCl buffer, extract (0-100 μl) and 30 μl of 70 μM freshly prepared sodium nitroprusside. The volume was made up to 300 μl with water before incubation at 37°C for 1 hr. The colour reaction was developed by adding 300 μl 8.1% SDS (Sodium Doudecyl Sulphate) to the reaction mixture containing SI, this was subsequently followed by the addition of 600 μl of acetic acid/HCl (PH 3.4) mixture and 600 μl 0.8% TBA (Thiobarbituric Acid). This mixture was incubated at 100°C for 1 h. TBARS (Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Species) produced were measured at 532 nm and the absorbance was compared with that of standard curve using MDA (Malondialdehyde).

Data analysis

The results of the replicates were pooled and expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Student t-test [22] One Way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) and the Least Significance Difference (LSD) were accepted at p ≤ 0.05.

Results

Proximate analysis

First, the proximate composition of heavy metals in the two varieties of municipal battery-dust leachates was investigated and the results are presented in (Table 1). The results revealed that mean value of all Municipal Auto Battery-Dust Leachates (MABDL) showed high significant level (p<0.05) of heavy metals than Elewi Odo Municipal Auto- Battery Recycling Site Leachate (EOMABRL). Also, both types are significantly higher than the permissible regulatory levels in the drinking water as recommended by NAFDAC, USEPA, FEPA and WHO (Table1).

| Heavy metal | MABDL | EOMABLL | WHO | USEPA | FEPA | NAFDAC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average(ppm) | (ppm) | (ppm) | (ppm) | (ppm) | (ppm) | |

| Cadmium | 1.417a | 0.003 | 0.005 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Cobalt | 1.867a | 0.049a | - | - | 0.00 | |

| Chromium | 21.833a | 0.068a | 0.005 | 0.1 | 0.05 | 0.00 |

| Copper | 28.4a | 0.341a | - | 1.0 | 0.3 | 0.00 |

| Iron | 5.04a | 2.66a | - | 0.3 | 0.05 | 0.00 |

| Manganese | 1.837a | 7.84a | - | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.00 |

| Molybdenum | 2.037a | ND | - | - | - | 0.00 |

| Nickel | 2.457a | 0.048a | - | - | - | - |

| Lead | 7.14a | 0.015a | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Selenium | 2.25a | ND | - | - | - | - |

| Zinc | 2.92a | 1.26 | 5.00 | - | - | 5.00 |

Table 1: Proximate Composition of heavy metals in Municipal battery-dust leachate (MABDL) and Elewi Odo Municipal battery recycling site leachate (EOMABRL). MABDL and EOMABRL are significantly higher (ap<0.05) than the Permissible levels of heavy metals in drinking water recommended by World Health Organization (WHO), United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA), Federal Environmental Protection Agency, 1991 (FEPA) and National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control (NAFDAC).ND= Not detected.

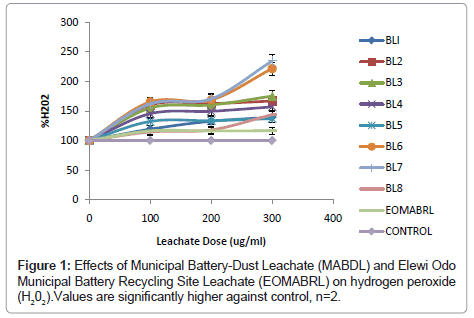

Production of reactive oxygen species: The ability of battery-dust leachate to induce hydrogen peroxide was determined and the results are presented in (Figure 1). The results revealed that all varieties of Municipal Auto Battery-Dust Leachates (MABDL) and Elewi Odo municipal auto-battery recycling site leachate (EOMABRL) showed high significant induction level (p<0.05) of H2O2in a dose-dependent manner than their corresponding control. Leachates (BL2, BL3, BL6, BL8 and EOMABRL) depicted marked elevation of H2O2 by 66.84%, 75.17%, 121.80%, 134.69% and 66.67% respectively at the highest dose.

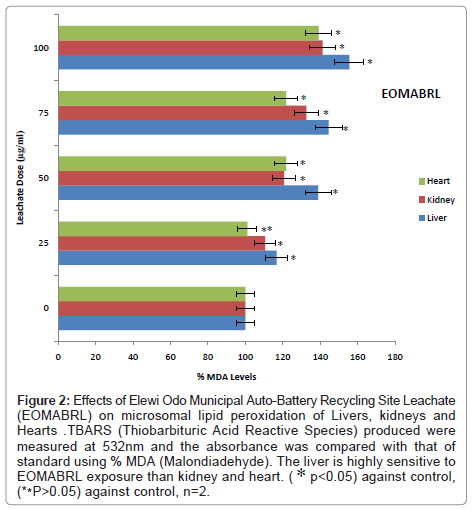

Marker of oxidative damage: In order to explore the possibility that municipal battery-dust leachate interferes with the structural cell membrane of the liver, kidney and heart. The levels of malondialdehyde (MDA) i.e. lipid degradation products, a maker of oxidative damage was evaluated. Incubation of liver, kidney and heart tissues with Elewi Odo Municipal Auto- Battery Recycling Site Leachate (EOMABRL) caused a significant (p<0.05) increase in the MDA content in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 2). MDA levels of EOMABRL were significantly (p<0.05) elevated in the liver, kidney and heart by 55.56%, 41.3% and 39.13% respectively compared to the corresponding control at the highest dose of 100 μg/ml (Figure 2). Consequently, the liver exhibited high levels of MDA contents than kidney and heart at the range of 0-100 μg/ml. The trend of susceptibility to EOMABRL exposure is as follows: Liver> Kidney> Heart.

Figure 2: Effects of Elewi Odo Municipal Auto-Battery Recycling Site Leachate (EOMABRL) on microsomal lipid peroxidation of Livers, kidneys and Hearts .TBARS (Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Species) produced were measured at 532nm and the absorbance was compared with that of standard using % MDA (Malondiadehyde). The liver is highly sensitive to EOMABRL exposure than kidney and heart. ( ∗ p<0.05) against control, (**P>0.05) against control, n=2.

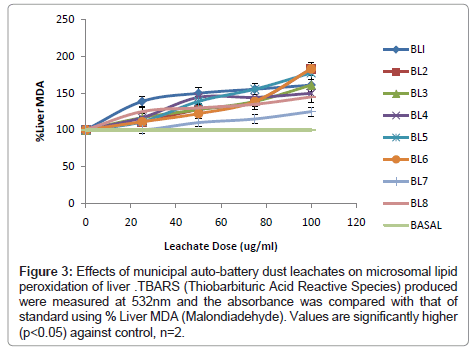

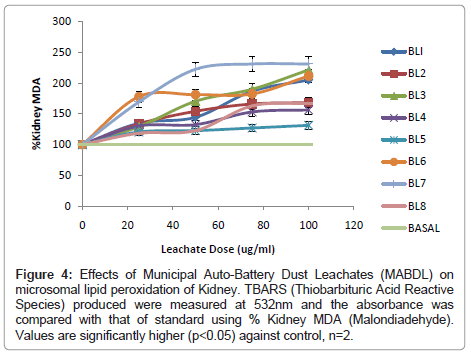

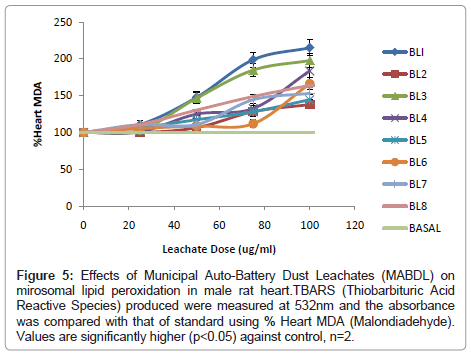

In addition, the effects of 8 Municipal Auto-Battery Dust Leachates (MABDL) on levels of Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances (TBARS) were also investigated in livers, kidneys and hearts of male albino rat and the results are presented in (Figure 3-5). Formation of MDA levels significantly (p<0.05) increased in rat livers, kidneys and hearts treated with MABDL in a dose dependent manner compared with the corresponding control. MABDL exhibited high levels of MDA contents than EOMABRL in all tissues tested. For livers, the MDA levels significantly (p<0.05) increased in a dose dependent manner. The rats treated with varieties of battery leachates such as BL4, BL6 and BL8 (MABDL) exhibited the highest MDA levels in the liver tissue by 177.78%, 183.33% and 183.3 % MDA respectively at the highest dose of 100 μg/ml (Figure 3). For kidneys, the MDA levels significantly (p<0.05) increased in a dose dependent manner. The rats treated with battery leachates (BL1, BL2, BL3 and BL4) showed the highest percent MDA levels in the kidney tissue by 205.44, 211.96, 295.65 and 231.52 respectively at the highest dose of 100 μg/ml (Figure 4). For hearts, the rat treated with battery-dust leachates (BL1 and BL3) shows the highest percentage MDA levels of 215.2 and 197.83 at the 100 μg/ml dose (Figure 5) consequently, the kidney exhibited high levels of MDA contents than heart and liver at the range of 0-100 μg/ml. The trend of susceptibility to MABDL exposure is as follows: Kidney > Heart > Liver. This then indicate that exposure to both MABDL and EOMABLL could induce oxidative damage in livers, kidneys and hearts through induced lipid peroxidation.

Figure 3: Effects of municipal auto-battery dust leachates on microsomal lipid peroxidation of liver .TBARS (Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Species) produced were measured at 532nm and the absorbance was compared with that of standard using % Liver MDA (Malondiadehyde). Values are significantly higher (p<0.05) against control, n=2.

Figure 4: Effects of Municipal Auto-Battery Dust Leachates (MABDL) on microsomal lipid peroxidation of Kidney. TBARS (Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Species) produced were measured at 532nm and the absorbance was compared with that of standard using % Kidney MDA (Malondiadehyde). Values are significantly higher (p<0.05) against control, n=2.

Figure 5: Effects of Municipal Auto-Battery Dust Leachates (MABDL) on mirosomal lipid peroxidation in male rat heart.TBARS (Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Species) produced were measured at 532nm and the absorbance was compared with that of standard using % Heart MDA (Malondiadehyde). Values are significantly higher (p<0.05) against control, n=2.

Discussion

Hydrogen peroxide is a weak oxidizing agent and can inactivate a few enzymes directly, usually by oxidation of essential thiol (-SH) groups. It can cross cell membranes rapidly and inside the cell, H2O2 probably reacts with Fe2+ or other redox metals possibly Cu2+ ions to form hydroxyl radical, which may be the origin of many of its toxic effects [23]. Our present study showed increased induction of H2O2 and OH• in a dose-dependent manner by rat treated with MABDL and EOMABRL. This indicates an increased free radical generation. Our present data are in agreement with the observation that heavy metals contained in the leachates can cause deleterious effects by catalyzing hydrogen peroxide (H202) decomposition to produce OH• via Fenton reaction. All Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) attack and damage body cells if comes in contact to get the missing electron they need. These heavy metals however, have implicated to have significant effects on some types of cancers such as primary tumours, including colon [11] and pancreatic cancer.

Lipid peroxidation, which is considered an indication of oxidative stress in animal tissues, can be induced via Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS). They are generated as a result of heavy metal toxicity in animals’ tissues. MDA is the decomposition product of polyunsaturated fatty acids of bio-membranes and its increase shows the extent of membrane lipid peroxidation [24]. Formation of MDA levels in our present study significantly increased in the treated rat- tissues (liver, kidney and heart). Both leachates exercabate MDA levels in a dose dependent manner. MABDL exhibited high levels of MDA contents than EOMABRL in all tissues. Oxidative damage to bio-membrane as a result of induced lipid peroxidation in the treated tissues with both MABDL and EOMABRL can be primarily attributed to the presence of heavy metals and other possible toxic constituents (Table 1). Higher levels of MDA contents in MABDL is equally linked to elevated concentration of heavy metals and other possible toxic compounds that are present in the leachate. These metals are redox active and catalyses the generation of hydroxyl radical and other toxic oxygen species especially Cu2+ and Fe2+ [25]. In contrast to redox, non-redox metals such as Zn, Ni, Cr and Pb cannot produce ROS directly, but generate oxidative stress by interfering with the animal’s antioxidant defence system [26-28]. Similarly, the characterised metals in the present study may have contributed to increased MDA levels. Besides disrupting membrane lipids, heavy metals are known to induce oxidative damage to proteins and DNA (25).

In addition, the production of MDA contents in our present study was significantly elevated in the liver in a dose dependent manner. The apparent increase in MDA levels of rat liver treated with both MABDL and EOMABRL suggests its predisposition to free radical damage. Our results are in agreement with the findings of Guangke et al. [29]. He said that mice exposure via drinking water from landfill leachate in Xingou elevated liver MDA levels.

Similarly, our present study caused a significant level in MDA in rat kidney tissue in a dose dependent manner compared with the corresponding control. MABDL also exhibited high levels of MDA than EOMABRL in the kidney tissue. This shows that both MABDL and EOMABRL could cause potential kidney dysfunction via lipid peroxidation of the membranes by making the kidney nephrons to compromise in their functions especially during the ultra-filtration of the blood. Consequentially, giving rise to nephritis.

Furthermore, this present study also investigated the effect of the MABDL and EOMABRL on the heart tissue of rat by measuring the MDA levels. It was observed that the MDA levels increases significantly in dose dependent manner in the two varieties of leachates compared to the corresponding control. Similarly, MABDL exhibited high levels of MDA level than EOMABRL in heart tissue. This then indicate that both MABDL and EOMABLL could induce various cardiovascular diseases such as myocardial infarction, inflammation of the heart etc.

Moreover, the incubation of the leachates with liver, kidney and heart tissues caused a significant increase in the MDA content. The mechanism by which heavy metals cause these deleterious effects is through heavy metal (Cu2+, Pb2+, Fe2+, etc.,) catalyzed hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) decomposition to produce OH• via Fenton reaction [30-32].

Conclusion

The varieties of leachates significantly (p<0.05) increased MDA level in the liver, kidney and heart in a dose-dependent manner. The Municipal Auto-Battery Dust Leachate (MABDL) has stronger induction ability of lipid peroxidation than Elewi Odo Municipal Auto-Battery Recycling Site Leachate (EOMABRL). The kidney showed high susceptibility in exposure to Municipal Battery-Dust Leachate (MABDL) than liver and heart while liver is highly sensitive to EOMABRL exposure than kidney and heart. Collectively, the possible mechanism by which both varieties of battery leachates exert nephritis, hepatitis and cardiovascular malfunctioning is through high induction of lipid peroxidation. In addition, the mechanism by which heavy metals caused these deleterious effects is through heavy metal (Cu2+, Fe2+ Pb2+ etc.,) catalyzed hydrogen peroxide decomposition to produce OH• via Fenton reaction. Hence, it is therefore imperative to provide adequate treatment measures to treat and/or prevent the exposure to MABDL and EOMABRL in order to minimize and/or eliminate their possible contamination/effluents in drinking waters.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest and that the authors of this manuscript have no financial or personal relationship with any organisation which could influence the work.

References

- Henry J, Heinke G (1996) Environmental Science and Engineering. Prentice Hall, Oxford, UK

- Yedla S, Parikh JK (2002) Development of a purpose built landfill system for the control of methane emissions from municipal solid waste. Waste Manag 22: 501-506.

- Chain E.S.K., and DeWalle F.B. (1976). “Sanitary Landfill Leachates and Their Treatment†ASCE, Journal of Environmental Engineering Division, Vol. 102, No. EE2, Pp 411-431.

- Kelley, W.E. (1976). “Ground-Water Pollution near a Landfill†ASCE, Journal of Environmental Engineering Division, Vol. 102: No. EE6: Pp 1189-1199.

- Lo IMC (1996) Characteristics and Treatment of Leachates from Domestic Landfills. Environment International 22: 433-442.

- Masters, G. M. (1998). “Introduction to Environmental Engineering and Science†Prentice-Hall of India Private Limited, New Delhi, India.

- Kumar, D., Khare, M., and Alappat, B.J. (2002). “Threat to Groundwater from the Municipal Landfills in Delhi, India†Proceedings of the 28th WEDC Conference on ‘Sustainable Environmental Sanitation and Water Services’, Kolkata (Calcutta), India Pp 377-380.

- Kumar D, Alappat BJ (2005) Analysis of leachate pollution index and formulation of sub-leachate pollution indices. Waste Manag Res 23: 230-239.

- Ahn DU, Wolfe FH, and Sim JS. (1993) The effect of metal chelators, hydroxyl radical scavengers, and enzyme systems on the lipid peroxidation of raw turkey meat. Poultry Sci 72: 1972-1980

- Cvetkovic D and Markovic D (2010) Beta-carotene suppression of benzophenone-sensitized lipid peroxidation in hexane through additional chain-breaking activities. Radiation Physics and Chemistry 80: 76-84.

- Kumpulainen, J.T and Salonen, J.T. 1996.atherosclerosis and cancer prevention,", The Royal Society of Chemistry: Cambridge, UK.

- Decker E.A, and Hultin H.O. (1992.) Lipid peroxidation in muscle foods via redox iron. In: Lipid Peroxidation in Foods. ACS

- Ladikos D, Lougovois V. (1990). Lipid peroxidation in muscle foods: A review. Food Chem. 35: 295-314

- Kanner J (1994) Oxidative processes in meat and meat products: Quality implications. Meat Sci 36: 169-189.

- St Angelo AJ (1996) Lipid oxidation on foods. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 36: 175-224.

- Wang W, Freemark K (1995) The use of plants for environmental monitoring and assessment. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 30: 289-301.

- Perket CL, Krueger JR, White hurst DA (1982) .The use of extraction test for deciding waste disposal options. Trends in Anal. Chem. 1(14): 342 – 347

- AOAC, (1990). Official methods of analysis, 15th edn Association of official Analytical

- Ohkawa H, Ohishi N, Yagi K (1979) Assay for lipid peroxides in animal tissues by thiobarbituric acid reaction. Anal Biochem 95: 351-358.

- Miller MJ, Sadowska-Krowicka H, Chotinaruemol S, Kakkis JL, Clark DA (1993) Amelioration of chronic ileitis by nitric oxide synthase inhibition. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 264: 11-16.

- Blokhina O, Virolainen E, Fagerstedt KV (2003) Antioxidants, oxidative damage and oxygen deprivation stress: a review. Ann Bot 179-194.

- Arora A, Sairam RK, Srivastava GC (2002) Oxidative stress and antioxidative system in plants. Current Science 82: 1227–1238.

- Garnczarska M, Ratajczak L (2000). Metabolic responses of Lemna minor to lead ions II. Induction of antioxidant enzymes in roots. Acta Physiol Plant 22: 429–432

- Aravind P, Prasad M.N.V (2003). Zinc alleviates cadmium-induced oxidative stress in Ceratophyllum demersum L.: a free floating freshwater macrophyte. Plant Physiol Biochem 41:391–397

- Panda S.K, Choudhury S (2005). Chromium stress in plants. Braz J Plant Physiol 17:95–102

- Guangke Li, Nan Sang, Dongsheng Guo. (2006).Oxidative damage induced in hearts, kidneys and spleens of mice by landfill leachate. Chemosphere 65: 1058-1063

- Bayir H, Kochanek PM, Kagan VE (2006) Oxidative stress in immature brain after traumatic brain injury. Dev Neurosci 28: 420-431.

- Oboh G, Shodehinde S.A (2009). Distribution of nutrients, polyphenols and antioxidant activities in the pilei and stripes of some commonly consumed edible mushrooms in Nigeria. Bulletin of Chemical Society of Ethiopia 23(3): 391-398

Citation: Akintunde JK, Oboh G (2012) In Vitro Oxidative Damage Induced in Livers, Hearts and Kidneys of Rats Treated with Leachate from Battery Recycling Site: Evidence for Environmental Contamination and Tissue Damage . J Clin Exp Pathol 2:129. DOI: 10.4172/2161-0681.1000129

Copyright: © 2012 Akintunde JK, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 16009

- [From(publication date): 11-2012 - Dec 22, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 11141

- PDF downloads: 4868