Bacteriostatic Effect of Lemon Fruit Juice: It's Potential as an Oral Rinsing Agent

Received: 12-Jun-2018 / Accepted Date: 25-Jun-2018 / Published Date: 04-Jul-2018 DOI: 10.4172/2332-0702.1000243

Keywords: Oral rinse agent; Lemon fruit juice; Antibacterial activity

Introduction

Lemon fruit (Citrus limon) has various health-promoting effects such as suppression of an increase in blood pressure and improvement of fat metabolism [1]. It has been used in some cases to prevent the mouth thirst of patients in hospitals [2]. Furthermore, it has been reported to have antimicrobial activity [3] and confirmed effective against Vibrio cholerae [4,5]. Therefore, lemon juice is considered effective for disinfection of drinking water [6]. In addition, since lemon juice inactivates Escherichia coli O157:H7, Salmonella enteritidis, and Listeria monocytogenes, which can cause food poisoning, the rationality of cooking methods using lemon juice, has been proven [7]. The effects of lemon juice on Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus subtilis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Salmonella Kintambo, and Salmonella typhi have also been investigated [8]. Furthermore, against Candida albicans, lemon juice has been shown to be more effective than gentian violet and has been reported to be useful for the management of oral candidiasis in South Africa [9]. The citric acid in lemon juice binds to norovirus particles, which may reduce viral infectivity [10]. Povidone-iodine (PVP-I) is known to be useful for oral care. However, its frequent use can destroy mucous membranes, and thus cause invasive infections [11]. Therefore, in this study, we investigated the usefulness of lemon juice for routine oral care by comparing its antibacterial activity with that of PVP-I solutions.

Materials and Methods

Detection of the effect on oral bacteria

Concentrated, 100% reduced lemon juice (undiluted solution [uLJ]; Pokka lemon 100, Pokka Sapporo Food and Beverage Ltd., Aichi, Japan; pH 2.3) was used. An undiluted PVP-I (uPVP-I) solution (Meiji mouthwash, Meiji Seika Pharma Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) containing 7% (w/v) PVP-I with 0.7% available iodine was also used. To prepare the oral rinsing solution, uPVP-I solution was diluted 20-fold (dPVP-I) and uLJ was diluted to 30% (v/v) (dLJ) with sterile distilled water (SW).

Two healthy individuals in their twenties and without tooth decay were enrolled as subjects. The subjects brushed their teeth 1 h before the experiment and did not eat, drink, or talk until the end of the experiment. The subjects rinsed their mouth 5 times by gargling with 10 mL of sterilized physiological saline (0.9% NaCl). The expelled liquid was preserved on ice as a pre-treatment solution until culture. Thereafter, the subjects rinsed their mouth 30 times by gargling with 10 mL of rinsing solution (SW, dLJ, or dPVP-I), before spitting it out. The subjects repeated this operation 5 times. Three hours after the last rinse, the subjects rinsed their mouth by gargling with 10 mL of sterilized physiological saline, and the expelled liquid was stored on ice until culture. Each of the solutions stored on the ice was diluted 1000-fold with sterilized physiological saline and 100 μL was inoculated on blood agar medium (Pourmedia@ Blood Agar E-MP23, Eiken Chemical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). After culturing at 37°C for 48 h under aerobic conditions, the colonies formed were counted. Thirty experiments were performed for each rinsing liquid, and the rate of increase in colony formation (%) associated with each rinsing solution was determined by considering the number of colonies associated with the pretreatment solution as 100%.

Minimum inhibitory and bactericidal concentrations

The optical density of E. coli DH5α (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan) cultured in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (1% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, 1% NaCl) was determined at 550 nm (OD 550), after which the culture was inoculated on LB agar medium (1.5% agar was added to LB medium). The colonies were counted and a conversion graph for OD 550 and colony-forming units (CFUs) was drawn (data not shown). The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was determined by the macro-broth dilution method (NCCLS, 1990). The uLJ or uPVP-I solution was diluted to 50, 45, 40, 35, 30, 25, 20, 15, 10, 5, 4.5, 4, 3.5, 3, 2.5, 2, 1.5, 1, and 0.5% (v/v) using two-fold and normal concentration of Mueller Hinton (MH) medium (BBLTM Mueller Hinton II Broth, Becton, Dickinson and Company, New Jersey, USA). E. coli was seeded at each dilution to a final concentration of 5 × 105 CFU/mL. The 96- well plates were then incubated for 16 h at 37°C. One microliter of the solution was taken from each well after observation, and it was inoculated in Mueller Hinton (MH) agar medium (1.5% agar was added to MH medium). Microbial growth was investigated after culturing at 37°C for 24 h. The lowest concentration at which growth was not observed was considered as the MBC. The average concentration of twenty results was determined and compared between the uLJ and uPVP-I solutions.

Ethics statement

In compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki, we explained the study and the methods to the subjects and obtained written consent from them. The study plan was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Health and Welfare of the Prefectural University of Hiroshima (17MH007).

Results

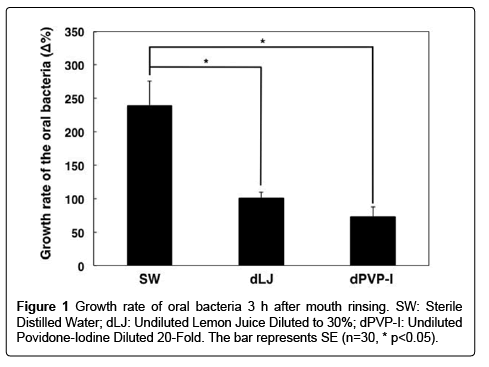

Figure 1 shows the % of bacteria after oral rinsing when the CFUs associated with pre-treatment solutions were considered as 100% (n=30). After rinsing with SW, the CFUs increased by 239.58% (standard error, ± 36.51) after 3 h. The % of bacteria associated with the dLJ solution was 101.34% (standard error, ± 8.51) and that associated with the dPVP-I solution was 73.25% (standard error, ± 13.93). Welch’s t-test showed that the % of bacteria associated with the dLJ and dPVP-I solutions were significantly different from that associated with SW (p<0.05). However, the difference in % of bacteria between the dLJ and dPVP-I solutions was not significant.

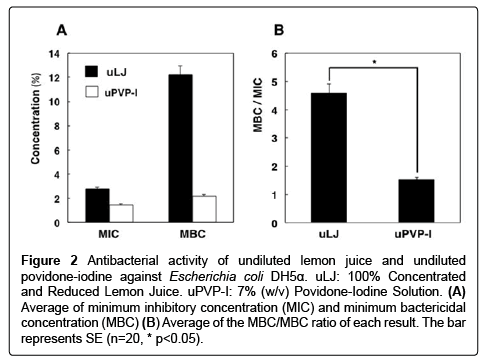

Figure 2A shows the average MIC and MBC values of uLJ and uPVP-I solutions for E. coli DH 5α (n=20). The MIC value of the uLJ solution was 2.78% (v/v, ± 0.12) whereas the MBC was 12.25% (± 0.68). The MIC value of the uPVP-I solution was 1.43% (± 0.10) whereas the MBC was 2.16% (± 0.17), corresponding to 0.01% (w/v) and 0.015% effective iodine, respectively. The mean values of the MBC/MIC ratio for individual results were calculated (Figure 2B). The mean value for the uLJ solution was 4.58 (± 0.32) whereas that for the uPVP-I solution was 1.53 (± 0.08). The mean value of the MBC/MBC ratio was significantly different between the two solutions (p<0.05).

Figure 2: Antibacterial activity of undiluted lemon juice and undiluted povidone-iodine against Escherichia coli DH5α. uLJ: 100% Concentrated and Reduced Lemon Juice. uPVP-I: 7% (w/v) Povidone-Iodine Solution. (A) Average of minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) (B) Average of the MBC/MBC ratio of each result. The bar represents SE (n=20, * p<0.05).

Discussion and Conclusion

It has been reported that the lemon fruit may be effective for various health issues such as cancer, cardiovascular disease, obesity, gastrointestinal disease, diabetes, urological diseases, psychosis, and bone protection [1]. Previously, we reported the possibility that lemon juice could suppress an increase in blood pressure [12]. Furthermore, various studies have reported the antibacterial activity of lemon juice [3-10]. However, we could not find previous studies wherein in vivo experiments were conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of lemon juice as an oral rinsing agent. Therefore, in this study, we compared the antibacterial activity of lemon juice with that of a commercially available mouthwash.

As Figure 1 shows, rinsing with lemon juice significantly suppressed bacterial growth. This study was performed in a small number of subjects and bacteria were not identified. Even for studies in a large number of subjects with different bacterial flora, the overall trend of findings is expected to be similar to that in this study. In this study, we detected bacteria of 3 h after oral care. We also preliminarily examined the bacterial culture 2 h after oral care; however, the results obtained for the rinsing liquids were not significantly different from that obtained for DW. It is conceivable that no significant difference appeared without a sufficient proliferation time. Therefore, if the incubation time is longer, the dPVP-I solution may have a significantly stronger effect than that of the dLJ solution.

The MBC/MIC ratio was significantly lower for the uPVP-I solution than for the uLJ solution (Figure 2). This means that the PVP-I solution was bactericidal, whereas lemon juice was bacteriostatic. In this study, the efficacy of lemon juice as an oral rinsing agent was evaluated against the commercially available E. coli strain DH5α, although it is better to use oral bacteria such as Streptococcus mutans for such a study. However, the results of this study afford the opportunity to determine the mode of action of lemon juice on general oral bacteria. Oral care agents with a high bactericidal activity may have stronger adverse reactions than those associated with bacteriostatic agents [13]. Frequent use of PVP-I solutions in hospitals can lead to infection due to microbial invasion of tissues. Thus, it might be advantageous to use lemon juice for oral care instead of PVP-I solutions.

It is known that organic acids have antimicrobial activity [14]. Lemon juice contains abundant citric acid [15], which has antibacterial activity [16,17]. These facts suggest that the bacteriostatic effect in this study was mainly induced by low pH due to the presence of citric acid. A report put forth by the World Health Organization (WHO)/Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) points out that acidic substance in fruit juice can cause tooth erosion without the involvement of bacteria [18].

The studies that were the basis of this report, are based on the results of frequent ingestion of many fruit juices. Since the dLJ solution used in this experiment contained 30% fruit juice and rinsing with 10 mL of the dLJ solution was repeated 5 times, the lemon juice consumed in one experiment can be considered as 0.5 fruit (30 mL/one lemon fruit). In addition, a previous study reported that exposure to citric acid for 1 h is necessary for tooth erosion to occur [19], the duration of rinsing in this study was less than 1 min on the whole. Furthermore, in this study, the subjects effectively kept their mouth closed for 3 h after rinsing. Lemon juice is known to promote salivation [20], and saliva exposure for 2 h has been reported to re-harden the citric acid-softened enamel [21]. Thus, it was considered that rinsing as performed in this study would not cause tooth erosion unless done frequently in a day.

The following two issues need to be addressed in future studies. The first is the concentration of the dLJ solution. The dLJ solution used in this study had a strong sour taste and was unsuitable for daily use. Further, it may be better not to rinse with lemon juice before sleeping because saliva flow is highly reduced during sleeping [22]. It has been also pointed out that frequent use of lemon juice may cause dry mouth [23]. Therefore, it is necessary to investigate the effect of lemon juice at a lower concentration and in a smaller amount. The second is the culture conditions for oral bacteria. Since the oral bacteria in this study were aerobically cultured, obligate anaerobes such as Porphyromonas gingivalis were not included in the results. Based on the above, further experiments are desired to use lemon juice as an oral rinsing agent.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors received generous editorial support from “Editage,” a division of Cactus Communications Co., Ltd. (Tokyo Japan).

References

- González-Molina E, DomÃnguez-Perles R, Moreno DA, GarcÃa-Viguera C (2010) Natural bioactive compounds of Citrus limon for food and health. J Pharm Biomed Anal 51: 327-345.

- Oikeh EI, Omoregie ES, Oviasogie FE, Oriakhi K (2015) Phytochemical, antimicrobial, and antioxidant activities of different citrus juice concentrates. Food Sci Nutr 4: 103-109.

- de Castillo MC, de Allori CG, de Gutierrez RC, de Saab OA, de Fernandez NP, et al. (2000) Bactericidal activity of lemon juice and lemon derivatives against Vibrio cholerae. Biol Pharm Bull 23: 1235-1238.

- Tomotake H, Koga T, Yamato M, Kassu A, Ota F (2006) Antibacterial activity of citrus fruit juices against Vibrio species. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 52: 157-160.

- D'Aquino M, Teves SA (1994) Lemon juice as a natural biocide for disinfecting drinking water. Bull Pan Am Health Organ 28: 324-330.

- Yang J, Lee D, Afaisen S, Gadi R (2013) Inactivation by lemon juice of Escherichia coli O157:H7, Salmonella Enteritidis and Listeria monocytogenes in beef marinating for the ethnic food kelaguen. Int J Food Microbiol 160: 353-359.

- Wright SC, Maree JE, Sibanyoni M (2009) Treatment of oral thrush in HIV/AIDS patients with lemon juice and lemon grass (Cymbopogon citratus) and gentian violet. Phytomedicine 16: 118-124.

- Koromyslova AD, White PA, Hansman GS (2015) Treatment of norovirus particles with citrate. Virology 485: 199-204.

- Sato S, Miyake M, Hazama A, Omori K (2014) Povidone-iodine-induced cell death in cultured human epithelial HeLa cells and rat oral mucosal tissue. Drug Chem Toxicol 37: 268-275.

- Kato Y, Domoto T, Hiramitsu M, Katagiri T, Sato K, et al. (2014) Effect on blood pressure of daily lemon ingestion and walking. J Nutr Metab 2014: 912684.

- Kalghatgi S, Spina CS, Costello JC, Liesa M, Morones-Ramirez JR, et al. (2013) Bactericidal antibiotics induce mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative damage in mammalian cells. Sci Transl Med 5: 192ra85.

- Matsuda T, Yano T, Maruyama A, Kumagai H (1994) Antimicrobial activities of organic acids determined by minimum inhibitory concentrations at different pH ranged from 4.0 to 7.0. Nippon Shokuhin Kogyo Gakkaishi 41: 687-702 (in Japanese).

- Penniston KL, Nakada SY, Holmes RP, Assimos DG (2008) Quantitative assessment of citric acid in lemon juice, lime juice, and commercially-available fruit juice products. J Endourol 22: 567-570.

- Daly CG (1982) Anti-bacterial effect of citric acid treatment of periodontally diseased root surfaces in vitro. J Clin Periodontol 9: 386-392.

- Georgopoulou M, Kontakiotis E, Nakou M (1994) Evaluation of the antimicrobial effectiveness of citric acid and sodium hypochlorite on the anaerobic flora of the infected root canal. Int Endod J 27: 139-143.

- World Health Organization (2003) Diet and dental disease. Report of a joint WHO/FAO expert consultation, WHO Technical Report Series.

- Tanishima A, Inukai J, Mukai M (2015) Effects of acid type, pH value, and immersion time on enamel hardness. Journal of Dental Health 65: 2-9.

- Murugesh J, Annigeri RG, Raheel SA, Azzeghaiby S, Alshehri M, et al. (2015) Effect of yogurt and pH equivalent lemon juice on salivary flow rate in healthy volunteers: An experimental crossover study. Interv Med Appl Sci 7: 147-151.

- Alencar CR, Mendonça FL, Guerrini LB, Jordão MC, Oliveira GC, et al. (2016) Effect of different salivary exposure times on the rehardening of acid-softened enamel. Braz Oral Res 30: e104.

- Humphrey SP, Williamson RT (2001) A review of saliva: Normal composition, flow and function. J Prosthet Dent 85: 162-169.

- O'Reilly M (2003) Oral care of the critically ill: A review of the literature and guidelines for practice. Aust Crit Care 16: 101-110.

Citation: Kato Y, Otsubo K, Furuya R, Suemichi Y, Nagayama C (2018) Bacteriostatic Effect of Lemon Fruit Juice: It’s Potential as an Oral Rinsing Agent. J Oral Hyg Health 6: 243. DOI: 10.4172/2332-0702.1000243

Copyright: © 2018 Kato Y, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 27753

- [From(publication date): 0-2018 - Dec 08, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 26192

- PDF downloads: 1561