Children and Nature in Tukum Village: Indigenous Education and Biophilia

Received: 04-Oct-2016 / Accepted Date: 11-Nov-2016 / Published Date: 18-Nov-2016 DOI: 10.4172/2375-4494.1000320

Abstract

Objective: Currently there is a consensus that the actual environmental crisis is resulting from intensive human appropriation of the environment and its creatures and processes. These disconnect between people and nature, characteristic of Western urban culture, also generates consequences on children's quality of life. The general objective of this study is to access indigenous children's environmental perception in its cognitive and affective aspects. In this direction we highlight the role of indigenous school practices in the improvement of biophilia and environmental awareness. Methods: Our qualitative survey adopt a multimethod approach that access children environmental perception from drawing sessions and interviews. The participants are 15 students and their teacher from the Tukum School, one of the 10 indigenous schools from the Tupinambá of Olivença visited in our research from 2014 to 2016. The Tupinambá community is located in Ilhéus, Bahia in Northeast region of Brazil. Results: Our results demonstrate that daily life in natural environments promoted both by culture and by indigenous school promote biophilia and, consequently, environmental awareness among children. The drawings also proved to be a suitable tool to access the feelings and children's knowledge about nature. Conclusion: Western education model that promoted the gap between children and nature can take inspiration in indigenous education in order to promote biophilia and the prevention of health and mental problems among urban children.

Keywords: Indigenous education, Tupinambá of olivença, Environmental perception, Biophilia, Drawings

218374Introduction

The physical and symbolic distance between nature and Western human societies is both cause and consequence of growing urbanization since the late nineteenth century. In general, this process consolidated a hierarchy between humans and other beings and natural processes; and inside of man himself, between what the mind rationalizes and what the body feels. The concept of rational education also crystallized the supremacy of intellectual, managerial and bureaucratic activity over menial and manual jobs. This detachment from nature is accompanied by a series of social changes, which have enabled a range of technological achievements, allowing man to initiate and lead an avid exploitation of the natural resources in a consumerist and unequal model of development. As a result, problems arose from various sources, especially environmental ones which have been aggravated by the frenetic pace of consumption and misuse of natural resources adopted by contemporary societies [1]. In short, the crisis we are experiencing is a result of this rampant appropriation of the environment and its creatures by humanity.

In the same direction Western or conventional school model is characterized by isolation from the surround context and, above all, natural environments. Today there is a growing research field that points out problems in child development caused by the deprivation of free and direct interactions with the creatures and environments of nature [2,3]. Other investigations were also able to confirm that children who interact recurrently with nature tend to better know it and esteem it [4-6]. In this sense, many educators have sought to value approaches that enable children to interact more often and so little mediated with other beings and living systems of the planet. In this sense, much has been learned from the education models of traditional and indigenous communities that integrate nature and culture in their life style and pedagogical orientation. These communities give us the insight that environmental and childhood issues are intrinsically connected.

This paper is about a survey with Tupinambá’s community, specifically their interaction with the natural environments in school period. As we will see below, this Brazilian indigenous community faces many challenges to preserve their ethnic identity from the first contact with Europeans in the sixteenth century. Our general objective was describing children’s perception and knowledge about the natural beings and systems. For this goal we access children’s perception and feelings about nature from their drawings and interviews. We also analyze video records of interaction between children and their natural environments during the school period. Teachers of indigenous schools were also interviewed so that we might better understand what teaching strategies are used in daily activities in the natural environment around the school.

This article first highlights some theoretical issues that guide our survey, especially the relationship between childhood and environmental issues. The biophilia concept helps us to understand the closeness between children and nature in an ecological approach of developmental psychology. Thereafter, we present our method and tools and describe the historical and local background. Then we present and discuss our results and advance some ideas about children-nature interactions and the adequate strategies to access children environment perception and feelings about nature and living beings. Finally, we advance some issues that we consider important for the improvement of pedagogical practices that include the natural environment in everyday school life.

Childhood and Biophilia

From the discussion initiated in "The Social History of Childhood and Family" by the French historian Philippe Aries, it was possible to determine the historicity of the concept of childhood and that of the child's world [6]. According to Ariès, the lack of a history of childhood and its late historical record are a sign of failure on the part of the Western adult to see the child in its historical perspective. Thus, both education and research about childhood understood it as a natural and universal phenomenon in its development. For a long time, at least in the Western world, every child in any social-historical and cultural context was merely considered as the past of adult life, a being whose biopsychosocial goal was to develop into maturity. In other words, for a long time, researchers, doctors and educators shared an adult centred perspective. Today there is an academic agreement that the concept of childhood is determined according to culture, its value is directly linked to the role it plays in the community and the social context. However, we now know that not every culture or society sees children as potential adults. In recent years, the historical field of childhood broke with the strict rules of traditional, institutional and political research to address issues and problems related to social history [7]. A more child centred perspective is now available to researchers and educators who want to build a new approach to child development and natural environmental participation in this process.

In this order, influenced by the important environmental wave already addressed in the introduction which urges us to seek other points of view and approaches, we have taken a holistic, ecological and interdisciplinary perspective. In the field known as Ecological Psychology, we seek to highlight the importance of the environment during the process of cognitive development in children, given that in addition to exposing the different ecological dimensions of this context, Ecological Psychology updates the active character of the child's participation in their environment and consequently in their development. The peculiarity of the child and their way of learning is no longer seen as immaturity or a distortion of reality but reveals the inventive process that guides cognition [8].

Thus, from the perspective of Ecological Psychology, the development of children is a multidimensional phenomenon; it affects the immediate context in their biophysical and social aspects but also the environment in its broader and even global dimensions. Human children have a history of co-evolution with other natural beings and processes which brings us to the concept of biophilia formulated by Wilson to refer to people’s attachment to what is alive, an innate tendency to affiliating to natural things [9]. Therefore, biophilia is characterized as a spontaneous attachment to nature and all living things on Earth, a natural feeling in biological organisms that coevolved in natural environments.

However, this does not mean that we are pre-programmed to always seek natural areas but prone to certain preferences. Our biophilic condition takes place in a socio-historical and cultural context that can either promote the interactions between people and beings and the natural environment in their different phases of the life cycle or not [4,10,11]. According to Wilson, there are sensitive periods during childhood and adolescence in which it is very easy to learn new things and develop preferences or antipathies towards natural environments, their beings and processes [9]. Hence, critical stages of stimulating biophilia are conditioned to interactive experiences with nature, promoted by the cultural context of which the subject is part. Although we share the idea that certain stages of childhood are more conducive to strengthening biophilia we will not in this work seek to define these periods. We start from the idea that the indigenous cultural context reinforces the biophilia at all stages of life, since its cosmology understands human beings and their culture as an integral part of nature. Thus, we believe that the daily and direct contact with the natural environment and nature beings leads to a pro-environmental predisposition. In the same direction Pyle argues for the centrality of direct contact with nature for children's environmental attitudes and thus to the future sustainability of the planet [2].

Strategies and Methodological Tools

Research with children and not researching the children themselves becomes an expanded exercise in terms of the conception of infancy or childhood that we will focus on, given the idea that to understand their experiences one must not only observe and interrogate them but in addition to our questions, allow them to formulate new questions they consider relevant to the issue that we bring, for example the interaction with nature.

In order to understand this wide generational group from a biological and socio-cultural point of view, it is essential for the relationship between the theoretical assumptions (who is the child in the world?) and the methodological devices (how to research them?), which underpin the entire research trajectory [8,12]. This work is the result of an extensive research project whose main objective is to describing Tupinambá children’s perception and knowledge about the natural beings and systems. This study met all ethical requirements required by Brazilian law and obtained informed consent from all participants and their parents. We research ten schools and interviewed 117 and 15 teachers.

Generally speaking, the research set out to conduct a descriptive study of what is "being a child" in this context, describing the interactions between children, educators, school space and natural environments. To this end we have adopted a multi-method strategy, aiming to "describe and assess, as accurately as possible, one or more characteristics and their relationships in a particular group" [13], given the complexity of the studied phenomenon, the interaction between children and educators within the indigenous school context.

The multi-method strategy basically puts different techniques of observation of environmental interactions into action, looking for different ways to approach the problem in order to reduce the bias of the researcher and pave the way for a qualitatively significant research [14]. The methods and tools used were drawings produced by children, interviews with children and teachers about their feelings and attitudes in regard to nature and indigenous belonging, as well as video record of educational activities in natural surroundings close to the school. The analysis of drawings to approach perception and environmental knowledge has already been adopted in various investigations and proved to be an appropriate tool of expression for children of what they consider relevant and significant in relation to the proposed theme [5].

As we described below our study involved 10 schools but in this article we will concentrate mainly on the analysis of the drawings and interviews produced by the children of the Tukum village. Our focus in this article will be directed to the feelings and environmental attitudes of children. Some excerpts from an interview conducted with their teacher about the choice of natural environments as a place for educational activities will also be presented and discussed. In this article we will not have the analysis performed on the video recordings that will be the subject of another article still in production.

The research team was composed of the authors of this article and other undergraduate students. Our survey took place after an initial introductory visit which was accompanied by a member of the Tupinambá community. During our visits we proposed to children a drawing session on the theme of environment and nature. Squareshaped paper and a box of crayons in 12 different colours were made available. It is important to note that in schools is not common availability of drawing materials. Still we did not observe any resistance or difficulty by children in relation to the proposed activity. After each drawing was done, the children were interviewed about the contents of their work, their knowledge on the subject as well as their experience and feelings in regard to nature and indigenous condition. On all occasions the children had the opportunity to add what seem to them appropriate and important. During the interviews we used audio recorder devices and, sometimes, the meeting was video recorded.

On a different occasion previously agreed with the teachers of each school, we have performed video records of the children’s outdoors activities. These activities were carried out by teachers in their respective school hours. Teachers, often accompanied by other members of the community whom they consider relatives, brought the children to natural spaces outside the school such as the river, hills, farming areas and socializing spaces such as clearings under the shade of jackfruit and other trees of the Atlantic Forest. On these occasions the teachers were interviewed as previously reported.

During our months in the field, we have faced many challenging situations that extended from institutional bureaucracy of our university for the provision of the required four-wheel drive cars to get to the villages, the successive stoppages and strikes by the staff working in the indigenous schools due to late payments from the third parties and contractors hired by the state of Bahia, to the bad weather that hampered access to roads and activities outside the classroom. However, the always affable reception from teachers and especially the children was a strong motivator for us to continue with the field work and to feel welcomed by the leaders and other community members in the best possible way.

Tupinambá’s Schools

The school is an achievement of the struggle of Tupinambá people by affirming their ethnic identity and resistance in recognition of their territory, totaling 47,000 hectares and extending across the towns of Ilhéus, Una and Buerarema in Bahia, in the Northeast region of Brazil. This strip of land was determined by FUNAI, the government agency of indigenous issues, since 2009 but has not yet been ratified by the Brazilian justice. This judicial leniency has raised conflicts between the Tupinambá people, landowners and small farmers. Over time, about 23 schools were implemented in the communities in order to contemplate the over 5 thousand indigenous people living in the area [15]. The outlines of the Brazilian indigenous differentiated education determined by national guidelines are: inter-culturalism, which provides access to technical and scientific knowledge of the national society, without ignoring the cultural aspects of their communities; bilingualism, in this case learning the native language Tupi, as encouraged by the songs and teaching elements present in the daily lives of students; an equally specific education, with the development of curricula and programs containing cultural aspects of the community; and finally a differentiated education scheme to offer educational materials unlike those of other education systems. Therefore, it is important to note that indigenous education, commonly interpreted as something reserved to isolated tribes, in the case of Tupinambá, clashes with that interpretation since they live in relationship with non-indigenous groups since the year of 1500. Is this sense, the exchanges with other cultures and their indigenous traditions begets a dialectical context where "indigenous schools produce a certain kind of Indigenous tradition and education" [16], making the boundaries between traditional and school education increasingly flexible and even non-existent at times.

In sum, the daily life of children Tupinambá is marked by children's games involving natural environment and its elements. The trees, the beach, the river, mangroves, these are life scenarios and also the play sites of children of that community. This immersion in the natural world makes playful situations and provides improvement of knowledge and skills about nature [11]. As Nunes, the indigenous childhood is marked by a huge freedom in the experience of time and space, and equity through the relationships whit the other members of the tribe, prior to the transition to adulthood which then opens and limits very precise constraints [17]. Early childhood is therefore a time of sociability and informal education, predominantly playful character, and lived according to the cultural peculiarities of the contexts in which it unfolds. In everyday, community activities are carried out without strict deadlines, often organized by seasonality and weather conditions, allowing children to participate playfully tasks of their group, at different levels of integration.

Tukum School

The Tukum School, analyzed in this paper, was founded in 2007 to meet the educational demands of indigenous children and adults inhabitants of the Tukum Village land recovery. It holds a significant area of the preserved Atlantic Forest, containing species of wild fauna and flora, especially native piaçava palms whose entire extraction process was run by Indigenous people at the behest of farmers; the latters, in addition to paying low wages to their workforce, created debt mechanisms in order to maintain their cheap and reliable indigenous labor. With the straw piaçava they are made rustic roofing for houses and beach huts and brooms. According to Ramon Tupinambá, the current cacique, these lands were traditionally occupied by his family and were expropriated by the Brazilian State during the last century and sold to large farmers.

This territorial recovery took place on October 8th, 2005 at 4:30 am, and the initiative was carried out by 22 indigenous. After their meetings, the village elders saw the expediency of placing their children and grandchildren in a school that were closer to their homes and requested the Brazilian State to host a school within their settlement. In present times, the Tukum School works in morning and afternoon shifts, the class that participated in our survey is composed of 15 students, aged between 8 to 10 years, which are in the second to fifth grade. The school obeys the indigenous guidelines as described before and has been establishing a close affective and practical link with the culture and traditional knowledge, in resistance to the colonizer and integrationist educational model put in place since Brazil was a colony. However, even if the guidelines of indigenous education are clear and mandatory, often, especially in communities with long continuous contact with the non-Indian world, teachers have a tendency to adopt pedagogical practices of Western conventional schools. In the case of Tupinambá schools, this occurs largely because teachers themselves were educated in mainstream schools and without specific training, and so tend to reproduce the pedagogical practices they experienced as students.

As highlighted in the introduction, schools are distancing their students from the natural environments since education become compulsory. This process especially affects children in kindergarten and the first grades; under the prerogative of hygiene and health, the practice of walling has become a reality ever more present in educational institutions in urban contexts and also in rural areas [11]. Going against this logic, the Tukum School extends beyond the physical limits of educational and learning spaces as they are commonly accepted such as the classroom, and stretches beyond the walls of taipa (mud house), which sustain the small building responsible for housing students and teachers; in addition to classes, it is used to host meetings from the movement against the struggle for land as well as space for medical care.

This space which is a "shapeshifter" in its features and with "fluid" borders allows the indigenous teacher Elenildes to explore the landscapes found in the Atlantic Forest biome, where the school and the village are both located. This precious location allows unique initiatives during the process of teaching and learning by the students, allying the transmission of disciplinary knowledge (Geography, Biology, Portuguese, and Mathematics) with the construction of ethnic knowledge in direct contact with the environment.

In the teacher’s words,

when I conduct some kind of activity I usually go under the trees in a cooler place in the shade (...) because it generates a feeling of safety and puts them more at ease (...) usually we work with music, sometimes that are tree songs, for example the jurema tree song speaks of the Earth. There are often times when I go outdoors with them and don’t touch the subject; if I'm going to talk about the trees or the Earth then we will sing and discuss the subject through music. Elenildes, age 28 (indigenous name Cendy, that means Light in tupi language).

Certain natural resources such as the jurema tree, present in the cultural universe of many indigenous populations of the Northeast; or the river that cuts through the village are part of everyday life, creating sustainable relationships between the ethical values of environmental protection and the ethnic identity of the community members, converging again for a sense of belonging to the territory and the living elements of the ecosystem.

Tupinambá Childhood and Nature

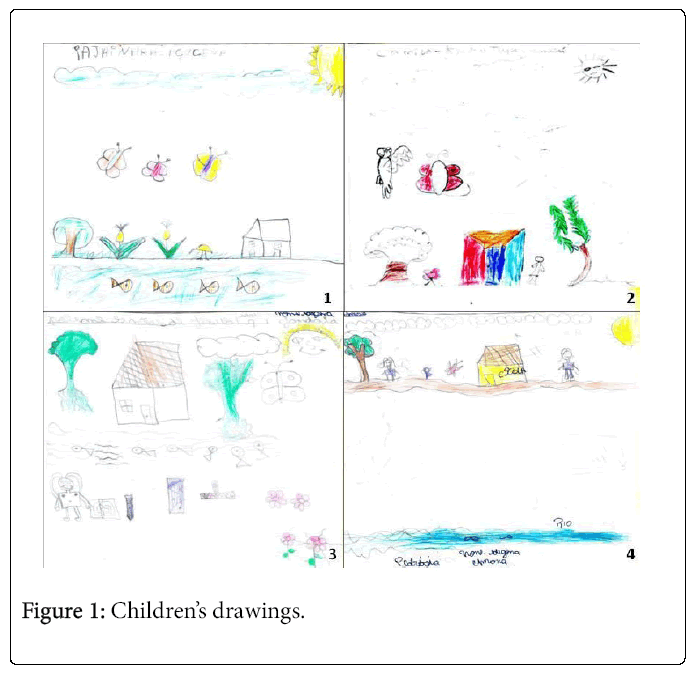

In this session we bring some drawings and interviews of children in order to identify their perceptions and feelings about the natural environment, and to highlight some aspects of their ecological knowledge and their ethnic belonging. As we noted above, the Tukum School group who participated in our research has among eight to ten years old. Based on a number of drawings made by the students, we could see how the elements of the biotic and abiotic environment are represented by the children. Especially the trees, the river and the school are constituted as preponderant elements in the drawings, denoting their importance in the universe of these children (Figure 1).

An important feature that we can see in these drawings is the indigenous and non-indigenous names signature in each artwork. This detail reveals their feeling of identity with dual belonging, since the legal ethnic recognition process of this group is still very new and does not complete the time span of a full generation, as we described. The significance of indigenous names was clarified by the teacher Elenildes and the young chief of Tukum community, Ramon. A ten years old girl named Jainara (1) also signed her indigenous name Açucena, that means a flower that grows in the river bank in the tupi language; Camila (2), aged eighth, signed Kyara, a little marsupial animal from the Rain Forest; Poliane (3), ten years old, signed her indigenous name Jandaia that means a species of bird form the parrot family; and finally Pedrisia (4), also with ten years old, signed Amona that means rain in the original indigenous language. As we can see the names of the children in the Tupi language refers to animals, plants and natural phenomena, reinforcing people’s closeness and belonging to the natural world and, in that sense, strengthening biophilia.

Another feature that should be taken into consideration is the size scale that the authors of the drawings chose to represent the natural elements, anthropomorphic figures and built structures. They represent the elements of fauna and flora on a larger scale and position, the river and its inhabitants in the south of the school, where in fact it is located. When they leave school, in order to get to the river bank, the students need to go down by a slope through the village. Therewith, the children allow us to understand that these same elements are endowed with greater importance to them in relation to others, revealing their geographical knowledge, but at the same time, their appreciation and sense of belonging which is characteristic of the concept of biophilia. The piaçava tree is also shown in two drawings brought in this article (2 and 3). It is, as we have seen, an important species both for the cultural reproduction of Tupinambá as to the local economy.

Even if the theme proposed for the drawings was the nature, almost all children included the school and people in their landscapes. This shows that for the research participants the natural world and the human world are not mutually exclusive. In contrast, traditional communities, including indigenous, do not present a dichotomous worldview that separates people from other living beings, characteristic of Western urban societies. This way of thinking about the relationship between nature and people seems more harmonious and close to sustainability.

In the words of children, when asked about the utility of nature, we can see a particular concern for their being which is characteristic of our biophilic condition promoted through the close contact with the natural world. The following is an excerpt from the interview with Camilla eight years old.

[Question] What’s your feeling about the nature? (Camila) To belong to nature.

[Question] What is the purpose of nature? (Camila)To take care of the people, give water to people, give many things for us.

[Question] What's good in nature? (Camila) Fruits, we play in nature.

[Question] What's bad in nature? (Camila) Nothing.

[Question] How do you think man’s relationship with nature should be like? (Camila) I don’t know, we have to take care of nature, we have to take good care, cannot mistreat, because nature brings everything to us, right?

In the course of Rafael’s speech we can testify a significant ecological knowledge that is able to identify the negative environmental impacts of human activities, such as drought in the sources of rivers due to deforestation of the riparian forests. He is ten years and his indigenous name is Kaya that means cajá, a tropical fruit from Rain Forest:

[Question] What’s your feeling about the nature? (Rafael)You cannot destroy. They cannot cut down the trees.

[Question] What is the purpose of nature? (Rafael) It’s for us, if we don’t destroy nature, the water is fuller but if man destroys nature, the river dries out.

[Question] What's good in nature? (Rafael) Birds singing.

[Question] What's bad in nature? (Rafael) Nothing.

[Question] How do you think man’s relationship with nature should be like? (Rafael) Man should not destroy as otherwise we will have no water.

In light of the above, we can conclude the kind of role that this school is playing in the educational process of Tupinambá children, not a rupture between the scholar and the indigenous knowledge, but a continuity in the direction of sustainable socio-environmental interactions, promoting the biophilia and the set of feelings that underlie our belonging to nature and its other living beings.

The outdoor activities described in the educator’s speech and the children drawings and interviews also allow us to infer that the use of unconventional teaching-learning methodologies, such as music, reinforces not only the cognitive aspects of knowledge but also their emotional dimension and belonging to the natural world. As previous studies have indicated, the drawing is an appropriate research tool for the assessment of children's environmental perception, even when the participating children do not have much practice. We can even advance the idea that drawing is a universal language capable of revealing both knowledge and feelings in relation to the proposed theme.

Final Considerations

Throughout this paper we discuss the environmental perception of children Tupinambá, more specifically what they feel for nature and also their ecological knowledge. All these aspects are crossed by ethnic and community belonging sponsored by the school and its teachers. Even if in the recent history school education has been a mischaracterization instrument of indigenous culture, currently the school is an important institution of cultural reaffirmation and transmission of traditional knowledge. After centuries, this institution brought by the colonizers was transformed into a major struggle and resistance tool by the Indigenous populations themselves. Nowadays, even under the conciliatory contradictions of the current government that advances in educational policies for indigenous people and to the same extent evades juridical issues related to demarcation of territories, the schooling institution protested as a bulwark of protection for cultural traditions and the fight to preserve biodiversity, transforming themselves into trusted teaching-learning spaces for the social transformations necessary for the continuity of the group itself and the quality of the environment.

We could highlight here the distance between what is communicated by national guidelines for indigenous differentiated education and the real schools and their actual effectiveness. Indigenous schools, despite their greater management autonomy, do not escape the problems of basic public education in Brazil, especially in the countryside and in the Northeast region. As we told, many times in our visits we could not execute such procedures, especially because of the suspension of classes for reasons such as lack of transportation to bring children to the school, no meals, non-payment of teachers and others employees such cooks. The conditions of school buildings are not always the best, many have no water supply or toilets, their equipment is scrapped, the available educational material is scarce and materials such as children's books, paper, toys, crayons, paint, glue, etc. are frequently missing. They are provided very sporadically. The remuneration of teachers is very low, in addition is often performed by temporary and precarious contracts with recurring delays. All these negatives would serve to justify the impossibility of indigenous education as stated in the national guidelines. However, our experience researching the Tupinambá schools led us to see beyond these limitations. We have in our data and memories the mark of an education that evades the difficulties that sabotage their viability, firmness and the commitment of teachers and other community contributors for it to happen and, above all, the enormous respect and reverence in relation to nature, its beings and processes. From the experience and the record of the school activities, it was possible to reflect on the role of schools, their formal and informal members and especially the children, who render "fluid" the boundaries between the classroom and nature, adapting them in the best possible way to group goals in their daily lives.

Based on this brief retrospective, the quality of the schools and the indigenous education can certainly be improved and this has been the struggle of the teachers and the community that we witnessed during our investigation. As for the quality of life for children, even with the economic precariousness we can say that when compared to the individually isolated and digital-connected urban children, they are marked by their freedom. Freedom of movement in the territory, affective proximity to educators, development of skills in recurrent interaction with nature, body presence in the production of knowledge, appreciation of manual skills and oral knowledge; in short, a positive statement of their culture. The Tupinambá childhood has much to teach us about how to prevent and combat illnesses and problems that are typical to the urban context as a sedentary lifestyle and the diseases that derive from it such as childhood diabetes and hypertension, let alone mental suffering as attention deficit disorder and depression, increasingly common in children. It also points us ways that seem obvious to promote the biophilic condition among all people and cultures, and also commitment to the protection of nature, its creatures and processes. Being in nature, interact with and learn from it, just so the link between people and natural environments can be strengthened, and the knowledge produced from these relationships will certainly be mobilized significantly to their conservation.

References

- Pereira F (2014) Educação Ambiental e Interdisciplinaridade: Avanços e retrocessos. Braz Geogr J: Geosci Humanities Res Med 5: 575594.

- Pyle R (2003) Nature matrix: reconnecting people and nature. Oryx 37: 206214.

- Crain W (2003) Reclaiming Childhood – Letting Children be children in our achievement oriented society. Times Books, New York.

- Chawla L (2006) Learning to love the natural world enough to protect it. Barn 2: 5778.

- Profice C, Pinheiro, J, Fandi A, Gomes A (2015) Children’s environmental perception of protected areas in the Atlantic Rainforest. Psyecol 6: 131.

- Ariès P (1962) Centuries of Childhood: A Social History of Family Life. Vintage, New York.

- Stearns P (2005) Growing up - The history of childhood in a global context. Bayleor University Press, Texas.

- Profice C, Pinheiro J (2015) Explorar com crianças - reflexões teóricas e metodológicas para os pesquisadores. Arquivos Brasileiros de Psicologia 61: 1122.

- Kahn P, Kellert S (2002) Children and nature: psychological, sociocultural and evolutionary investigations. MIT Press, Cambridge.

- Tiriba L, Profice C (2014) O Direito Humano à interação com a Natureza. In: Silva A, Tiriba L (Org.) Direito ao ambiente como direito à vida: desafios para a educação em direitos humano. Cortez, São Paulo 4777.

- Castro L, Besset, V (2008) Pesquisa-intervenção na infância e juventude. Trarepa/FAPERJ, Rio de Janeiro.

- Zeisel J (1981) Inquiry by design: tools for environment-behavior research. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Barker R (1965) Explorations in ecological psychology. Am Psychologist 20: 114.

- Brazil (1998) National Guidelines for Indigenous Schools. Ministry of Education, BrasÃlia.

- Cohen C, Santana V (2016) A Antropologia e as Experiências Escolares IndÃgenas. Repocs 13: 6186.

- Nunes A (2002) Crianças indÃgenas: ensaios antropológicos. Global, São Paulo.

Citation: Profice C, Santos GM, dos Anjos NA (2016) Children and Nature in Tukum Village: Indigenous Education and Biophilia. J Child Adolesc Behav 4:320. DOI: 10.4172/2375-4494.1000320

Copyright: © 2016 Profice C, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 5300

- [From(publication date): 12-2016 - Aug 24, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 4207

- PDF downloads: 1093