Concept of Recovery from Mental Illness

Received: 02-Jan-2023 / Manuscript No. jart-23-88063 / Editor assigned: 05-Jan-2023 / PreQC No. jart-23-88063 (PR) / Reviewed: 19-Jan-2023 / QC No. jart-23-88063 / Revised: 23-Jan-2023 / Manuscript No. jart-23-88063 (R) / Published Date: 30-Jan-2023

Abstract

Recovery from a mental disorder can have different meanings and can be defined differently by researchers. We defined recovery from mental disorder as used currently and its characteristics for improving quality of life of individuals with mental disorders and obtaining suggestions regarding nursing practice for them.

We used the method of conceptual analysis by Rodgers and Knafl to examine the use of the term “recovery.” This method focuses on concepts that change in response to time or situation and attempts to elucidate these continually evolving characteristics rather than visualizing concepts as fixed or static phenomena.

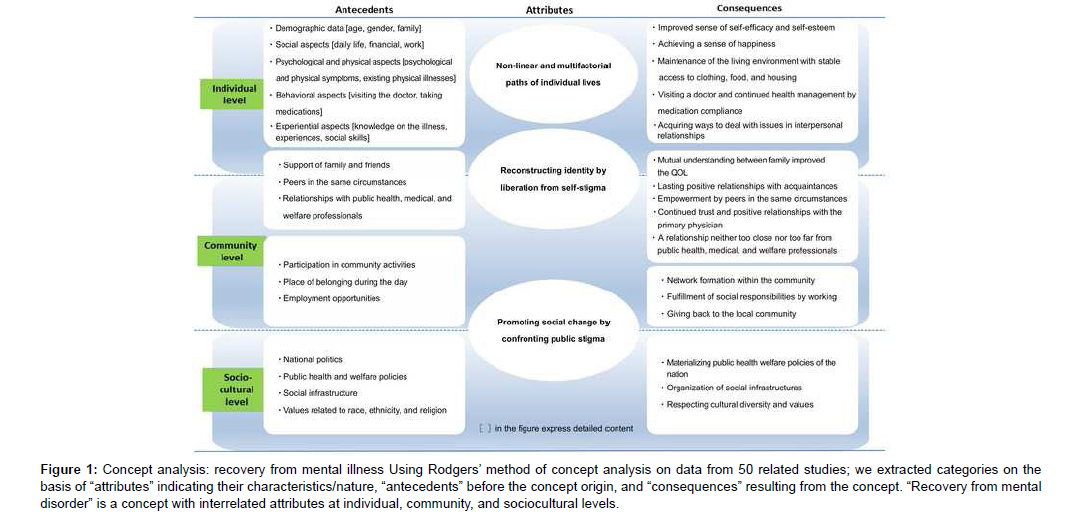

We used the database EBSCOhost (Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, MEDLINE, CINAHL Plus). We used Rodgers’ method of concept analysis on data from 50 related studies and extracted characteristic categories on the basis of “attributes” indicating their characteristics/nature, “antecedents” before the concept origin, and “consequences” resulting from the concept. Our concepts were broadly divided at the individual, community, and sociocultural levels, with each level overlapping with one another; there were involutions of attributes, and these processes formed the concepts. The concept of recovery from mental disorder was redefined. We propose its definition as “the nonlinear and multifactorial life journey of affected individuals to reconstruct identity through interpersonal, group, and community activities, helping to promote awareness on mental disorders through periodic context-based sociocultural interactions with the greater society.” The redefined concept of recovery is not limited to personal factors. This could become a fundamental material demonstrating the basis for mental health nursing intervention.

Keywords

Concept formation; Mental health recovery; Public health; Addiction

List of Abbreviations

OECD, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development QOL, Quality of life

Background

Matters related to mental health pose as serious problems worldwide. Although resources are insufficient and psychiatric care is given low priority in many countries, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [1], it is necessary for each country’s government to further enhance initiatives to improve psychiatric care. The mean number of beds at psychiatric hospitals of OECD member countries was 68 per 100,000 patients in 2011; this number is decreasing. Numerous issues are associated with providing regional care, with many people not receiving appropriate care. Recovery is related to returning individuals with mental illness to the community.

Since 1950, recovery for individuals with mental illness has been actively debated in developed countries, such as the USA. Recovery of individuals with mental illness was mentioned in the 2003 report of the President’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health [2]; interest in recovery-based activities, including the deinstitutionalization of those with mental illness and community reintegration, has been growing. Regarding multi-professional cooperation, nurses play a role in the support of mentally ill individuals.

Since 1950, recovery for individuals with mental illness has been actively debated in developed countries, such as the USA. Recovery of individuals with mental illness was mentioned in the 2003 report of the President’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health [2]; interest in recovery-based activities, including the deinstitutionalization of those with mental illness and community reintegration, has been growing. Regarding multi-professional cooperation, nurses play a role in the support of mentally ill individuals. mainly focuses on young individuals. Some seek to popularize the use of the term “recovery” without limiting it to individuals with mental illness [5].

Recovery can have many meanings depending on the context and is defined differently by different researchers.

Here we focused on recovery for individuals with mental illness and defined it for drawing suggestions for improving the quality of life (QOL) of individuals with mental disorders, while providing suggestions for nursing practice.

Approach to Concept Analysis

We used the method of conceptual analysis by Rodgers and Knafl to examine the use of the term “recovery.” Rodgers & Knafl’s approach focuses on concepts because they change in response to time or situation. The method attempts to elucidate these continually evolving characteristics rather than seeing concepts as fixed or static phenomena [6].

Data Sources

A literature review, using EBSCOhost (Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, MEDLINE with Full Text, CINAHL Plus with Full Text), explored the use of the term “recovery” from various perspectives, including nursing, medicine, psychology, and sociology. In examining the search range of the data, we considered historical backgrounds wherein this term was used. It possibly originated in autobiographical reports of individuals with mental illness. Since 2000, the US government offices began referring to the recovery of mentally ill individuals in public. Additionally, to promote recovery, the number of implementation research reports increased [7]. Notions of recovery spread globally, starting in developed nations; it is frequently debated, and many academic papers have been published on the topic. Therefore, we performed our literature search from 2000 (start of public debates) to 2015. The search identified 151 peer-reviewed articles containing the term “recovery” (mental disorders or mental illness) in the title, of which 33 were identified after checking the title and abstracts and judging the adequacy of each paper and inclusion criteria, corresponding to 20% of the total number of results necessary for data collection. We included autobiographical reports authored by individuals with mental illness before 1999 and papers and books frequently referenced in extracted literature. Review papers deemed necessary for concept analysis were incorporated; ultimately, our research focused on a corpus of 50 sources.

We focused on the manner in which this term was used in papers and collected data on categories representing the attributes or nature of phenomena; subcategories, which are antecedents of these phenomena; and codes, which result from the occurrence of phenomena. Data were organized based on Rodgers and Knafl’s [8] approach using an original coding sheet. Qualitative analysis was performed on extracted data in the framework of antecedents, attributes, and consequences to define the concept of recovery.

Evaluation of Findings

Our concepts were broadly divided at the individual, community, and sociocultural levels (Figure 1). Each level overlapped; there were involutions of attributes, and these processes formed the concepts. Herein, the conceptual attributes are mentioned in double quotes and specific examples in brackets.

Figure 1:Concept analysis: recovery from mental illness Using Rodgers’ method of concept analysis on data from 50 related studies; we extracted categories on the basis of “attributes” indicating their characteristics/nature, “antecedents” before the concept origin, and “consequences” resulting from the concept. “Recovery from mental disorder” is a concept with interrelated attributes at individual, community, and sociocultural levels.

Attributes

The concepts were classified into individual, individual-community, and community- sociocultural levels. The individual, community, and sociocultural levels intertwined with each other to form the attributes.

Individual level: A nonlinear and multifactorial path of life: Recovery is a life path itself and is described as nonlinear. Others suggest that recovery is a stage or an element. Recovery can be described as a process or a stage and is multifactoral.

Individual-community level: Reconstructing identity by liberation from self-stigma: Individuals with mental illness often have negative feelings about themselves. The ultimate obstacle for overcoming stigma is the challenge of self-stigma, i.e., re-writing a previously underevaluated identity into one granting individual rights in the process of identity formation. The self is capable of change and success is possible, while reaffirming one’s existence [9].

Specifically, there were statements about becoming conscious of possible and impossible things, such as confronting the illness and elderly individuals becoming aware of the purpose of work and achieving work-life balance [10]. Gaining a sense of life control, making choices, and selecting activities are important. Individuals strive to find hope by pursuing goals with a hopeful attitude regarding their lives or illnesses, even if symptoms continue. Negative and positive feelings coexist throughout these processes.

Community-sociocultural level: Promoting social change by confronting public stigma: Stigmas related to mental disorders are evident in all levels of society; there are similar stigmas in developed countries. Families fear how mental illness is perceived by the society and are generally fearful of having a family member’s mental illness exposed. Stigma at the sociocultural level has been referred to as the basis of stigma at the individual level and has a large impact on the construction of identity. Conversely, there are movements attempting to dispel the stigma of mental disorders worldwide that seek to increase the awareness of mental illnesses to counter public stigma [11].

Antecedents

Concepts of “recovery” were categorized into individual, individual-community, community, and sociocultural levels.

Individual level: [Age] relates to “demographic statistical data,” and there were descriptions of developmental tasks according to age group. [Gender] relates to these as well; men emphasized on work or money, whereas women emphasized on dealing with stress from interpersonal relationships. Comparative research seeks thought patterns that vary according to gender. We also extracted descriptions of [family configuration].

In terms of “social aspects,” [living environment], [economic condition], and [employment status] were extracted as attributes.

With regard to “physical and psychological aspects,” [psychological symptoms], [physical symptoms], and [existing physical illnesses] were extracted.

In terms of “behavioral aspects,” [visiting a doctor] and [taking medications] were extracted. There was a mixture of positive and negative opinions on taking medications.

In terms of “experiential aspects,” as seen in [knowledge on the illness] and [social experiences], upbringing and experiences such as specific diseases or treatment experiences had an impact. Furthermore, descriptions related to [social skills] were extracted.

Individual-community level: Some concepts fell under individual and community levels, including “support from family and friends”; “presence of peers in the same circumstances”; and “interactions with public health, medical, and welfare professionals” [12].

Community level: Recovery is promoted by “participation in community activities”. “Place of belonging during the day” was related to recovery, specifically in terms of performing daily tasks, sports or club activities, and life-long learning [6]. In terms of “employment opportunities,” many reports focused on securing employment opportunities and a place to work; the act of working promotes recovery.

Sociocultural level: In terms of “national politics, health, and welfare policies, and social infrastructures,” political or health and welfare policies affect recovery. In terms of descriptions on cultural background, descriptions related to “values associated with race, ethnicity, and religion” were extracted.

Consequences

We categorized concepts according to the individual, individualcommunity, community, and sociocultural levels.

Individual level: Recovery outcomes include “improved sense of self-efficacy and self-worth” and were also related to finding a new meaning and purpose to one’s life. Achieving goals gave individuals a sense of “acquiring happiness.” Gaining work- related skills and receiving monetary compensation were also linked to a sense of happiness.

“Maintenance of the living environment with stable access to clothing, food, and housing” included financial support and excellent assurance and arranging a stable living environment [13].

In terms of “continued health management by a visiting doctor and medication compliance,” continued doctor visits and understanding the importance of medications and medication compliance decreased psychiatric symptoms and sufficiently controlled symptoms.

In terms of “acquiring ways to deal with issues in interpersonal relationships,” there were reports on support system use, ways in which an individual interacts with others, managing and compensating chaotic situations that arise from illness, and recognizing how to perceive oneself, i.e., how to face oneself and come to terms with oneself.

In the qualitative research, the “routinization” of recovery was presented, which suggested that recovery is not a static point in time but a continuing and routinizing process [14].

Individual-community level: In terms of “mutual understanding between family and improved QOL,” there have been descriptions on parent-child relationships and family understands. “Continuing positive relationships with acquaintances” is also an element of social support. Having family or friends who knew the individual with mental illness prior to disease onset is also significant. Furthermore, in terms of “empowerment by peers in the same circumstances,” recovery was encouraged by making new connections with peers in the same circumstances [15].

In terms of “continuing trust and positive relationship with the primary care physician,” there are descriptions related to medications and continuing relationships by the cooperative approach of clinical physicians. “A relationship neither too close nor too far from public health, medical, and welfare professionals” involves keeping a reasonable distance as a team from people with mental illness and allowing them to make choices. As care methodologies, initiatives for employment with individual placement and support and evidencebased practice standards for people with mental illness have been reported. Furthermore, comprehensive support with assertive community treatment and descriptions on illness management and recovery has been reported. Health, medical, and welfare professionals provide support to people with mental disorders and their families [16].

Community level: Regarding “network formation in the community,” authors have described the spreading of community activities and links between peers in the same circumstances. Regarding “fulfillment of social responsibilities by working,” having a sense of meaning or purpose by being able to offer a work-related skill and giving something to others have been described. In terms of “giving back to the local community,” authors have described the importance and joy of meaningfully contributing to others’ lives.

Sociocultural level: Recovery depends on public health welfare policies in a nation.

Political initiatives also have an effect, and policy development varies among countries. Differences between social infrastructures in urban and rural areas exist; in developed nations, the “organization of social infrastructures” is also being promoted[17].

We found many descriptions of “cultural diversity and respecting values,” such as differences in Western and Eastern medical perspectives, including traditional Indian treatment methods, the Japanese culture of respecting others, and other attitudes or values specific to various ethnic groups [4]. Although faith is related to active recovery, it also plays a role in mental health disturbances. Faith is multifactorial and includes theoretical (financial or material support) and emotional support (empathy or advice).

Synthesis of Findings

Trend in the literature and spread of the concept of recovery: From the individual to sociocultural level

Research on the recovery of people with mental illness is found in various fields including nursing, psychology, and sociology, thereby confirming the expansiveness of the concept of recovery in psychiatry. Recovery mostly indicates that the disease is cured. However, in the present study, medical literature describing QOL and the meaning of living was also noted. Academic papers that describe the intrinsic nature of recovery and papers based on notions of recovery were found, with descriptions of actual initiatives and their results, from all over the world.

Many landmark references have described the intrinsic nature of recovery and presented recovery as an individualized activity. Conversely, concepts and practical reports based on the concept of recovery that spread worldwide since 2000 showed that in the background of individualized activity, there were impacts of sociocultural aspects, local communities or collectivities, and interactions with others [18].

The living environment, health management, and ability to maintain adequate human relationships are important; they form the basis for maintaining life in the individual level of people with mental disorders and healthy individuals. These concepts are fundamental to life. Life stability enhances a sense of happiness, self-efficacy, and selfesteem.

Networks widen through community interactions, and making contributions to a local community leads to self-satisfaction. By having a place of belonging during the day, individuals are able to discover a place of belonging other than their home, bringing them one step closer to social participation. Furthermore, by finding employment opportunities, individuals receive the support of others and also become the provider of labor, service, and products to the society [19].

The presence of family, friends, and peers in the same circumstances and health, medical, and welfare professionals who provide a link between the individual and the community is invaluable. These relationships themselves, indicated as consequences, lead to developing and reinforcing mutual relationships, while relationships with an adequate distance were also shown. Although the frequency of interaction with or the influences on people with mental illness varied, these interactions are significant in maintaining daily life [20].

In developed countries, the concept of recovery developed through cyclical relationships in policy-making processes and compromises at the individual and community levels. However, simultaneously, stigma against people with mental illness resulting from national, human rights, ethnic, and religious beliefs disrupted the concept of recovery.

Particularly, the concept of recovery has prevailed worldwide since 2000, and inconsistencies have become more apparent. Although the notion of recovery has many personal and individual aspects, it varies according to differences inherent to a country, society, or culture [21].

Descriptions regarding differences in sociocultural backgrounds are consistent with results of the systematic review by Leamy et al. [6] and this study further specified and emphasized this point.

The concept of recovery continues to evolve, not only as an individualized concept but also as a changing and diverse process.

Because of concept analysis in this study, we hereby define recovery of individuals with mental illness as follows:

The nonlinear and multifactorial life journey of affected individuals to reconstruct identity through interpersonal, group, and community activities, helping to promote awareness on mental disorders through periodic context- based sociocultural interactions with the greater society [22].

Utilization of the concept in nursing practice

Understanding and encouraging individuals with mental illness to utilize their strengths is essential in improving their QOL. These strengths may include the distinct features of the community, region, nation’s policies, or ethnic values. They may also include participating in community activities; visiting a place of belonging during the day; employment opportunities; the presence of family and friends; and public health, medical, or welfare professionals. Recovery of individuals with mental illness cannot be achieved single- handedly. We must consider differences in values, based on national policies or ethnicities [9]. It is important to consider the individual’s surroundings as strength.

The role of mental health nurses in the health care workforce is well placed; they have been considered as providers of productive and effective care [6]. Additionally, they play an important role in mental health nursing. Therefore, the role of public health nursing is also increasingly important.

Nursing care methods currently exist in various forms in local communities. Nurses may directly interact with individuals with mental illness, along with significant others such as family and friends, peers in the same circumstances, and physicians. Nurses may be directly involved with local residents or in the forming of networks. Nursing practices that make the best use of community and individual strengths are required [23,24].

Conclusion

Our concepts were broadly divided at the individual, community, and sociocultural levels, with each level overlapping with one another; there were involutions of attributes, and these processes formed the concepts.

Based on concept analysis, we defined recovery of individuals with mental illness as the nonlinear and multifactorial life journey of affected individuals to reconstruct identity through interpersonal, group, and community activities, helping to promote awareness on mental disorders through periodic context-based sociocultural interactions with the greater society.

These results suggested the importance of improving QOL of individuals with mental illness and helping them rediscover their strengths by considering the surrounding environment as strength in the current nursing practice.

The redefinition of recovery in individuals with mental illness, which was clarified in this study, holds strong significance for those involved in mental health nursing in mental health care, which involves various occupations. In particular, the viewpoint of approaching the patient themselves, their families, local communities, and governments could form a fundamental material demonstrating the basis for nursing intervention ranging from the treatment of psychiatric symptoms to proposals for government policies.

Conflict of Interest

There is no conflict of interest in this study.

References

- Vallieres EF, Vallerand RJ (1990) Traduction et validation Canadienne-Française de l’échelle de l’estime de soi de Rosenberg. Int J Psychol 25: 305-316.

- Walburg V, Laconi S, Van Leeuwen N, Chabrol H (2014) Relations entre la consommation de cannabis, le jugement moral et les distorsions cognitives liées à la délinquance. Neuropsychiatr. Enfance Adolesc 62: 163-167.

- García JA, Olmos FC, Matheu ML, Carreño TP (2019) Self esteem levels vs global scores on the Rosenberg self-esteem scale. Heliyon 5: e01378.

- Aluja A, Rolland JP, García LF, Rossier J (2007) Dimensionality of the Rosenberg self-esteem scale and its relationships with the three-and the five-factor personality models. J Pers Assess 88: 246‑249.

- De Aquino JP, Sherif M, Radhakrishnan R, Cahill JD, Ranganathan M, et al. (2018) The psychiatric consequences of cannabinoids. Clin Ther 40: 1448-1456.

- Karila L, Roux P, Rolland B, Benyamina A, Reynaud M, et al. (2014) Acute and Long-Term Effects of Cannabis Use: A Review. Curr Pharmaceutical Design 20: 4112‑4118.

- Guillem E, Pelissolo A, Vorspan F, Bouchez-Arbabzadeh S, Lépine JP (2009) Facteurs sociodémographiques, conduites addictives et comorbidité psychiatrique des usagers de cannabis vus en consultation spécialisée. L’Encéphale 35: 226-233.

- Guillem E, Arbabzadeh-Bouchez S, Vorspan F, Bellivier F (2015) Comorbidités chez 207 usagers de cannabis en consultation jeunes consommateurs. L’Encéphale 41: S7-S12.

- Dugas EN, Sylvestre MP, Ewusi-Boisvert E, Chaiton M, Montreuil A, et al. (2019) Early risk factors for daily cannabis use in young adults. Can J Psychiatry 64: 329-337.

- Sideli L, Quigley H, La Cascia C, Murray RM (2020) Cannabis use and the risk for psychosis and affective disorders. J Dual Diagn 16: 22-42.

- Glowacz F, Schmits E (2017) Changes in cannabis use in emerging adulthood: the influence of peer network, impulsivity, anxiety and depression. Eur Rev Soc Psychol 67: 171-179.

- Stapinski LA, Montgomery AA, Araya R (2016) Anxiety, depression and risk of cannabis use: examining the internalising pathway to use among Chilean adolescents. Drug Alcohol Depend 166: 109-115.

- Roberts B (2019) Legalized cannabis in Colorado emergency departments: a cautionary review of negative health and safety effects. West JEM 20 : 557-572.

- Blanco C, Hasin DS, Wall MM, Flórez-Salamanca L, Hoertel N, et al. (2016) Cannabis use and risk of psychiatric disorders: prospective evidence from a US national longitudinal study. JAMA Psychiatry 73: 388-395.

- Esmaeelzadeh S, Moraros J, Thorpe L, Bird Y (2018) The association between depression, anxiety and substance use among Canadian post-secondary students. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 14: 3241-3251.

- Van Damme P (2006) Dépression et addiction: Dans : Gestalt 2006/2 (no 31). Société française de Gestalt 1: 121-135.

- Leadbeater BJ, Ames ME, Linden-Carmichael AN (2019) Age-varying effects of cannabis use frequency and disorder on symptoms of psychosis, depression and anxiety in adolescents and adults. Addiction 114: 278-293.

- Hengartner MP, Angst J, Ajdacic-Gross V, Rossler W (2020) Cannabis use during adolescence and the occurrence of depression, suicidality and anxiety disorder across adulthood: findings from a longitudinal cohort study over 30 years. J Affect Disord 272: 98-103.

- Gage SH, Hickman M, Heron J, Munafò MR, Lewis G, et al. (2015) Associations of cannabis and cigarette use with depression and anxiety at age 18: findings from the Avon longitudinal study of parents and children. PLoS ONE 10: e0122896.

- Halladay JE, MacKillop J, Munn C, Jack SM, Georgiades K (2020) Cannabis use as a risk factor for depression, anxiety, and suicidality: epidemiological associations and implications for nurses. J Addict Nurs 31: 92-101.

- Danielsson AK, Lundin A, Agardh E, Allebeck P, Forsell Y (2016) Cannabis use, depression and anxiety: a 3-year prospective population-based study. J Affect Disord 193: 103-108.

- Delforterie MJ, Lynskey MT, Huizink AC, Creemers HE, Grant JD, et al. (2015) The relationship between cannabis involvement and suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Drug Alcohol Depend 150: 98-104.

- Duperrouzel J, Hawes SW, Lopez-Quintero C, Pacheco-Colón I, Comer J, et al. (2018) The association between adolescent cannabis use and anxiety: a parallel process analysis. Addict Behav 78: 107-113.

- Leweke FM, Koethe D (2008) Cannabis and psychiatric disorders: it is not only addiction. Addict Biol 13: 264-275.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Citation: Olabisi PB, Olanrewaju MK (2023) Concept of Recovery from Mental Illness. J Addict Res Ther 14: 507.

Copyright: © 2023 Olabisi PB, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Usage

- Total views: 2349

- [From(publication date): 0-2023 - Nov 09, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 1876

- PDF downloads: 473