ECT Dilemma: Should We Start This Treatment Earlier?

Received: 03-Oct-2018 / Accepted Date: 10-Nov-2018 / Published Date: 17-Nov-2018

Keywords: Psychosis; Benzodiazepines; ECT; Behaviour

Introduction

Catatonia is a complex condition, rare in young people and in Western countries, where it may therefore be difficult to recognize or may be misdiagnosed by inexperienced staff. Early detection is the key to starting a life-saving treatment such as (ECT) in a timely manner.

Early intervention with ECT should be encouraged to avoid undue deterioration of the patient’s physical condition in those with catatonic states [1-3]. However, evidence suggests that the commencement of ECT is often procrastinated and thus it may be underused [3].

Case Presentation

The subject is a 31-year-old man who had been diagnosed with HIV during routine check-up in 2005.

He used drugs in a social context, mainly crystal methamphetamine and had a history of trauma, having been sexually assaulted early in 2015.

He was unknown to mental health services, but in October 2015 he was brought to the emergency department (A&E) by his mother. This had been precipitated by weeks of abnormal behaviour, with suspiciousness and veiled threats towards his mother. His behaviour had progressively deteriorated and he had become unreliable, irritable and bizarre [4]. He had been dismissed from work and had lost his shared tenancy due to a fight with another resident and had to move back with his mother. In A&E he was assessed as not meeting the threshold for admission to a psychiatric hospital and discharged back home with the recommendation to be follow up by the home treatment team [5].

However, the following day, he committed his index offence of arson with intent to endanger life. This consisted of setting multiple fires into his mother’s house, locking his mother inside a room and let the house dogs free. He was immediately charged and remanded to prison.

In February 2016, he was transferred from prison to our medium secure unit due to concerns about his mental health. On admission, he presented as mute with no eye contact and no response to verbal commands. He was observed to be staring at fixed points, or lying in uncomfortable-looking positions. A catatonic-state was diagnosed, but disputed by many staff [6].

Due to unresponsiveness, he had to be restrained to provide blood tests, which indicated a mild lymphocytosis with normal CRP, in keeping with the chronic inflammatory process of progressive HIV [7]. Based on these blood results, it was concluded that prior to the current clinical presentation i.e. unresponsiveness, he had been grossly compliant with his HIV medications [8].

He tested positive for syphilis, for which antibiotic therapy was prescribed.

MRI and LP showed normal results.

He did not present with any physical complication of HIV and his vital signs and other blood results were normal.

Given the possible catatonic presentation, He was treated with i.m. 2 mg lorazepam, to which he responded rapidly and started interacting with staff and enquiring ‘what is that stuff you gave me? I’ve got so much more energy’. However, within a few hours, he returned to a catatonic-like state.

SOAD (second opinion appointed doctor) approval for ECT was considered and discussed with the subject’s mother and the clinical team. Both felt very uneasy, refused the use of ECT and thought other options should be tried first, despite SOAD approval.

After two weeks of no improvement, ongoing catatonia interspersed with evidence of suspiciousness, poor memory (he couldn’t remember his index offence or the faces and names of staff) and continuous refusal of oral medication, an oral/i.m. olanzapine regime was started (i.e. a daily i.m. dose of olanzapine was administered when it had not been taken orally).

Lorazepam 2 mg daily was administered meanwhile with the same modality only on those days when he appeared more withdrawal. Following each administration of lorazepam, he was observed interacting well with staff, attending to his personal hygiene and eating the food provided. At this point he also agreed for the nurses to do his physical observations and accepted oral medication [9]. Due to his response to lorazepam, the idea of emergency ECT was put to one side.

By this time some members of the team, due to his “on-off” presentation following lorazepam administrations, became convinced that he was actually “choosing” to shut down at times, and that his presentation was due to an emerging personality disorder. This idea, coupled with the fact that many team members still considered it a barbaric procedure, contributed to a strong and vociferous opposition to ECT [10].

Due to continued concerns about ECT and repeated injections (the subject had a history of trauma and had been sexually assaulted prior to being arrested) olanzapine depot was introduced but its effects were, as expected, not immediate.

Further deterioration and refusal of any oral intake led to a regime of daily i.m. lorazepam (2-4 mg) which resulted in a rapid but shortlived improvement. He became able to divulge his mental state including depressed mood, suicidal thoughts, anhedonia, and communicated to staff that he was hearing an authoritarian judgemental voice, commanding him to self-harm. He described at times feeling like he “froze” as though he was paralysed and had to fight for any simple movement, to “get started”.

Informative meetings were held and Catatonia and ECT’s use and side effects were discussed. As the subject became able to communicate more, staff accepted that his symptoms were not faked and they come around to the idea that he might be catatonic after all. His lack of improvement meant that his mother also began to accept that he was catatonic. This understanding was crucial to staff and his’s mother ceasing to oppose ECT.

In differential diagnosis with bipolar disorder and neurological causes for catatonia, it was concluded that his presentation was in keeping with a severe depressive episode with psychotic symptoms and catatonia.

Following the first session of ECT in April, his level of activity appeared increased and longer lived throughout the day as opposed to one or two hours of activities after lorazepam.

As ECT sessions continued, his oral intake increased, his paranoia lessened and his interaction with ward staff and occupational activities improved. In May, all his oral medications were gradually re-started and his olanzapine depot was switched to oral medication as by this time he had become fully compliant with his oral medications. Soon after he was able to take up psychological therapy too. His mental state continued to steadily improve up until full remission of symptoms in July 2016. He required 5 ECT sessions in total; it was felt not necessary to complete a usual cycle of 6 sessions of ECT as his mental state had gone back to normal and he was fully compliant with all his oral medications. For other 4 months he remained in our unit where his mental state maintained stable.

Discussion

This subject developed catatonia despite his HIV infection being well controlled. A background of recent life stressors and illicit substances’ use may have contributed to the progress of his depressive psychosis and the prolonged period with no treatment in prison, most likely contributed to his catatonic symptoms. In keeping with catatonia, his symptoms responded well to i.m. lorazepam, however the improvements were short-lived. Complete and sustained remission of his catatonic psychosis only occurred with the use of ECT.

Several issues need to be acknowledged regarding the use of ECT. First of all, probably related to the fact that it has been used inappropriately in the past, including as a torture, there is a collective view that the practice of ECT is horrid and barbaric. Negative representations of ECT in the media and in films such as in “One flew over the Cuckoo's nest” have contributed to the increased stigma around ECT. In addition, ECT is indeed associated with some side effects, for example short memory loss, which can be particularly worrying for recipients. However, according to the evidence this side effect is only short-lived [11].

Inaccurate representation, exaggeration of its side effects and concerns about overuse and inappropriate use may increase the apprehension and stigma around ECT and result in reluctance for ECT to be used when it is appropriate and necessary to do so. This may contribute to individuals affected by treatable mental illness being held back from appropriate treatment and timely recovery [12], with obvious ethical and economic impact. Of note, most patients have a positive response and attitude towards ECT [13]. In his case, even though a catatonic state was suggested early into his admission, ECT treatment was resisted by the team and his relatives. This was primarily due to the stigma around ECT, which was seen as a very cruel, barbaric option. Our view is that the stigma surrounding ECT is so profound that staff preferred to believe that that he was “choosing to switch-onand- off” which made some staff dispute he was actually catatonic.

When in hospital, catatonia was suspected and diagnosed in our patient, but the idea of the best treatment i.e. ECT, was rejected because his relatives and many staff felt uneasy about this procedure, resulting in him remaining unwell possibly for longer than necessary [14]. This indicates that more training and education about ECT is required. Many staff had no knowledge of ECT other than what they had learned from the media or films. ECT use is rarer than before and this is most likely related to earlier treatment of severe mental health problems. It is imperative, however, that when ECT is appropriate, it should be used to reduce the longer-term risk to patients’ outcomes. Disclosure of scientific evidence, including its side effects, and guidelines on ECT should form part of the essential training for staff working on psychiatric wards. This is required to reduce the stigma and misinformation around the use of ECT, allowing patients to receive the best available treatment for their condition [15,16].

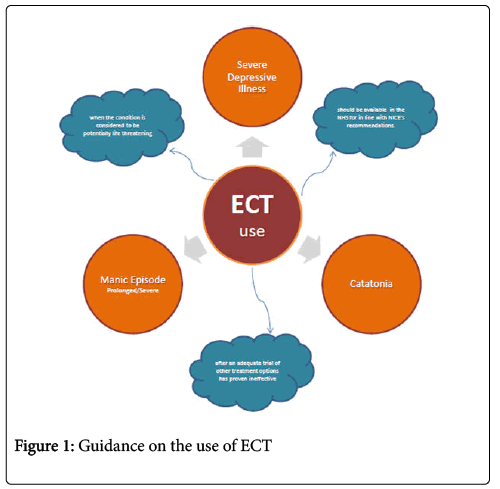

Our study suggests and confirms previous evidence that ECT should be considered in the early stages of treatment and it may be safer than antipsychotic therapy in HIV-positive patients. Patients should be treated with the best evidence-based treatment regardless of individual preconceptions and sensibilities (Figure 1).

References

- Bing EG, Burnam MA, Longshore D, Fleishman JA, Sherbourne CD, et al. (2001) Psychiatric disorders and drug use among human immunodeficiency virus-infected adults in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry 58: 721-728.

- Nebhinani N, Mattoo SK (2013) Psychotic Disorders with HIV Infection: A Review. German Journal of Psychiatry 16: 43-48.

- Sewell DD, Jeste DV, Atkinson JH, Heaton RK, Hesselink, JR et al (1994) HIV-associated psychosis: a study of 20 cases. San Diego HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center Group. American Journal of Psychiatry 151: 237-242.

- Volkow ND, Harper A, Munnisteri D, Clother J (1987) AIDS and catatonia. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 50: 104.

- Sienaert P (2011) What we have learned about electroconvulsive therapy and its relevance for the practising psychiatrist. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 56: 5-12.

- Reed J (2017) Why are we still using electroconvulsive therapy?. BBC Newsnight.

- Davis N, Duncan P (2017) Electroconvulsive therapy on the rise again in England. The Guardian.

- Pemberton M (2017) Dr Max the Mind Doctor: Barbaric? Electric shocks can save lives and are an invaluable weapon in the arsenal to fight depression. Daily Mail.

- Hriso E, Kuhn T, Masdeu JC (1991) Extrapyramidal symptoms due to dopamine-blocking agents in patients with AIDS encephalopathy. American Journal of Psychiatry 148: 1558-1561.

- McDaniel JS, Brown L, Cournos F, Forstein M, Goodkin K, et al. (2000) Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with HIV/AIDS. American Journal of Psychiatry 157: 1-62.

- Arshad M, Arham AZ, Arif M, Bano M, Bashir A, et al. (2007) Awareness and perceptions of electroconvulsive therapy among psychiatric patients: a cross-sectional survey from teaching hospitals in Karachi, Pakistan. BMC Psychiatry 7: 27.

- Luchini F, Medda P, Giorgi MM, Mauri M, Toni C, et al. (2015) Electroconvulsive therapy in catatonic patients: Efficacy and predictors of response. World Journal of Psychiatry 5: 182-192.

- Choy MM, Farber KG, Kellner CH (2017) Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT) in the News: Balance Leads to Bias. Journal of ECT 33: 1–2.

- Maguire S, Rea SM, Convery P (2016) Electroconvulsive Therapy - What do patients think of their treatment? Ulster Medical Journal 85: 182-186.

- Cohen D, Taieb O, Flament M, Benoit N, Chevret S, et al. (1997) Absence of cognitive impairment at long-term follow-up in adolescents treated with ECT for severe mood disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 157: 460-462.

Citation: Cappai A, Smith S (2018) ECT Dilemma: Should We Start This Treatment Earlier?. Psych Clin Ther J 1: 103.

Copyright: © 2018 Cappai A, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Usage

- Total views: 3728

- [From(publication date): 0-2018 - Dec 11, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 2831

- PDF downloads: 897