Large Ulcerating Congenital Infantile Fibrosarcoma of the Lower Leg: Case Report and Literature Review

Received: 08-Jun-2020 / Accepted Date: 22-Jun-2020 / Published Date: 29-Jun-2020 DOI: 10.4172/2472-016X.1000136

Abstract

Congenital infantile fibrosarcoma (CIFS) is a rare pediatric soft-tissue sarcoma and is typically detected in children <1 year of age. They usually present at birth but some present late up to the third moth of life. Histologically composed of relatively uniform spindle-shaped cells often organized in a herring-bone pattern, with a range of mitotic activity and differentiation.

Keywords: Congenital; Tumours; Gene fusion

Background

Well-differentiated tumors are typically composed of slender, elongated cells while poorly differentiated tumors have more round cells and tend to have less collagen deposition [1-3]. CIFS is highly associated with (12;15) (p13;q25) translocation, which creates an ETV6/NTRK3 gene fusion, although ETV6/NTRK3 fusion negative cases also have been described [4,5].

Case Presentation

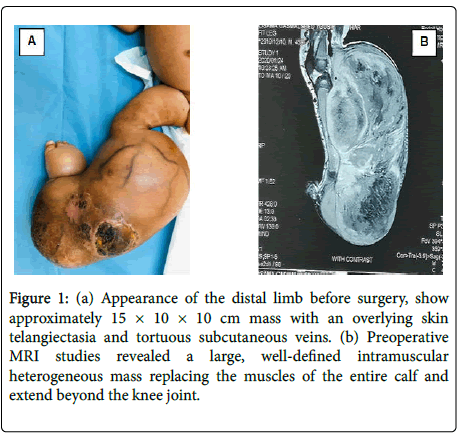

A 45 days old full-term boy presented with a large mass over the right leg. He was born by normal vaginal delivery 40 weeks after uncomplicated pregnancy. At the time of delivery, he was noted to have approximately 5 × 5 cm mass on his right leg. Initially it was misdiagnosed and treated conservatively as congenital hemangioma. However, the mass had rapidly increased in size, upon presentation examination show a firm, non-pulsatile mass approximately 15 × 10 × 10 cm in size, with an overlying skin telangiectasia and tortuous subcutaneous veins (Figure 1A). There was no lymph node swelling in the inguinal region. Musculoskeletal ultrasound revealed huge mass involving almost all flexor compartment of the leg with scattered necrotic zone. Mass was negative on Doppler study. MRI revealed a large, well-defined intramuscular mass replacing the muscles of the entire calf and extend beyond the knee joint, mass was heterogeneous with area of high T1? Hemorrhage, high T2 necrosis and enhancing solid mass completely encasing the neurovascular bundles (Figure 1B). The MRI findings were interpreted as being consistent with rhabdomyosarcoma. A biopsy was performed to ascertain the diagnosis. The histopathological examination showed dense cellular neoplastic spindle cells arranged in short interlacing fascicles with mild pleomorphism, and frequent mitoses. Immunohistochemistry stains were negative for SMA, myogenin and CD34, and positive for vimentin, scattered view cells show immune reactivity for S100. Based on these findings, a diagnosis of CIF was made. A staging with CT scan of the chest was performed and revealed (2 mm) nodules within the left upper and right lower lobes the rest is unremarkable. Her initial full blood count also showed hemoglobin of 6.3 g/patient receive packed RBCs before surgery. Above knee amputation was done, resection margin was involving with tumor the child was kept on close follow-up only, patient currently on remission with no evidence of local recurrence.

Figure 1: (a) Appearance of the distal limb before surgery, show approximately 15 × 10 × 10 cm mass with an overlying skin telangiectasia and tortuous subcutaneous veins. (b) Preoperative MRI studies revealed a large, well-defined intramuscular heterogeneous mass replacing the muscles of the entire calf and extend beyond the knee joint.

Discussion

Congenital infantile fibrosarcoma (CIFS) is a rare pediatric softtissue sarcoma and is typically detected in children <1 year of age [1,2]. Although 40% present of the cases present at birth some present late up to the third moth of life, as well as the antenatal period [3-7]. With some rare cases reported late in childhood [8], CIFS most frequently occur in the extremities with lower limbs more often affected than upper limbs [1,9]. But it also has been reported in the trunk and other extra skeletal locations [10-12]. Clinically, CIFS is classically presents at birth or shortly after as a growing mass that progressively enlarges into a firm, shiny tumor, often ulcerate and fixed to underlying tissues, as in our case [13]. CIFS is usually slow-growing, and tends to be more benign than fibrosarcoma in older children, which behaves more like the type found in adults although they are histologically similar [14]. Large ulcerating tumor early in life (Table 1) can present with significant hemorrhage or disseminated intravascular coagulopathy requiring emergency resuscitation [15]. The incidence of metastatic spread of disease is 5%-8%, rises to 26% when considering patients with axial tumors [16]. The organs commonly affected in metastasis are the lungs and lymph nodes. Metastatic disease may be verified on fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography [17]. Being vascular lesions, in addition to occasional cutaneous clinical presentation, CIFS may mimic vascular lesions on clinical grounds and in ultrasound evaluation, most frequently misdiagnosed as an infantile hemangioma or congenital hemangioma, contributing to a delay in diagnosis and treatment as was seen in the present case [18]. Other common differential diagnosis includes spindle cell rhabdomyosarcoma, infantile myofibroma and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans may also resemble CIFS clinically and histologically.

| References | Gender | Age | Location | Size, cm | Surgical procedure | Chemotherapy | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salman et al. [30,31] | Male | 2 months | Left arm | 8.3 × 5 × | Gross resection | Neo-adjuvant, VAC; 2 cycles | In remission at 3 |

| 2.7 cm | years of treatment | ||||||

| Kraneburg et al. [13] | Male | 36 w | Left lower leg | 11.8 × | Knee disarticulation amputation | No | In remission at 2 |

| 9.3 × 8.5 cm | years old | ||||||

| Dumont et al. [7] | Male | Prenatal | Right leg | 10.7 × 7.3 | Leg amputation | No | Died at day 8 of life |

| × | |||||||

| 8.6 cm | |||||||

| Kerl et al. [32] | Female | Newborn | Left elbow | 10 cm (in diameter) | Resection | Yes, VAC; 9 | In remission at 4 |

| cycles | years old | ||||||

| Duan et al. [33] | Male | 4 days | Left forearm, recurrent | 8 × 7 × | Resection; Amputation at | No | In remission |

| 6 cm | Supracondylar level at | ||||||

| Recurrence | |||||||

| Hashemi A et al. [8] | Female | 9 year | left hand recurrent | 4 × 5 cm | Resection | Yes oncovin, actinomycin | In remission |

| and endoxan. | |||||||

| Hamidah Alias [15] | Female | 7-week | right arm | 6 × 5 × 7 | Resection | Yes, Yes, neo- adjuvant VAC; 5 cycles | In remission at 3 years |

| cm | postopraive |

Table 1: Case report of large CIFS of extremity.

While there are no particular imaging findings to differentiate CIFS from other soft tissue tumors, MRI can often help to discriminate CIFS from benign vascular lesions, and is important for defining the extent of the lesion [19]. Furthermore, histologic evaluation remains critical for the early detection of CIFS, and FISH for The ETV6/NTRK3 gene fusion plays a vital role in uncovering the correct diagnosis and ultimately the proper therapy when microscopic appearance is equivocal. Histopathologic characteristics include a solid, dense proliferation of spindle cells in interlacing bundles; positive for vimentin, and occasionally for desmin, SMA, and cytokeratin [20]. Our case it was positive for vimentin, and negative for SMA, and myogenin, in addition to positive immune reactivity to S-100 protein. We could not test for the ETV6-NTRK3 gene fusion due to technical resource constraints. ETV6-NTRK3 transcript was present in 87.2% of patients where the investigation was performed by the European Pediatric Soft Tissue Sarcoma Study Group [21]. Previously, therapy for CIFS consisted primarily of surgical resection, often necessitating amputation in patients with extremity involvement [22]. Both neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapies have been used to reduce the risk of metastasis [23-25]. Recently, dual neoadjuvant therapy with vincristine actinomycin-D has been shown to be effective in a conservative, multidisciplinary approach to preserve functionality in the involved tissues by avoiding mutilating surgery [21]. Wide local excision, without any mutilating surgery, is the mainstay of management [26]. In cases of huge tumor size, where functional or anatomical derangement might jeopardize the quality of life in these children, neoadjuvant chemotherapy with vincristine and actinomycin-D (VA) might prove beneficial [6,27]. In cases, where a tumor-free margin is achieved, close follow-up without any adjuvant chemotherapy is sufficient.

Although the role of adjuvant chemotherapy has not been established, chemotherapy has been used postoperatively in cases with positive surgical margins or with residual tumor [24,28]. The European Pediatric Soft Tissue Sarcoma Study Group (Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study; IRS) has developed conservative treatment recommendations according to initial resectability of the tumor [21]. Initial surgery is suggested only if possible without mutilation. Patients with initial complete (IRS group I/R0) or microscopic incomplete (group II/R1) resection have no further therapy. Patients with initial inoperable tumor (group III/ R2) receive first-line VA chemotherapy. Delayed conservative surgery is planned after tumor reduction. Aggressive local therapy (mutilating surgery or external radiotherapy) is discouraged. The VA regimen is recommended as the first-line therapy in order to reduce long-term effects [21]. The risk of Local recurrence is considerably high, being 17%-43% of patients after conservative surgery alone [29]. Fortunately, they are usually treatable and rarely metastasize; with a reported curative rate of greater than 80% [30]. In the present case, complete gross excision with microscopic incomplete (group II/R1) tumor resection was the result of surgery the child was kept on close follow-up only, no evidence of local recurrence until date.

Conclusion

In conclusion, CIFSs should be kept in the differential diagnoses of soft tissue tumors in infants, even in congenital cases. The clinical picture is similar to some more common lymph vascular malformations which might lead to misdiagnosis. Surgical resection still the main treatment option aiming for complete excision. However, chemotherapy does have a good response and can be considered to avoid Aggressive local therapy (mutilating surgery or external radiotherapy). Overall survival in these tumors is excellent.

References

- Soule EH, Pritchard DJ, Pritchard DJ (1977) Fibrosarcoma in infants and children a review of 110 cases. Cancer 40:1711-1721.

- Coffin CM, Dehner LP (1990) Soft tissue tumors in ï¬rst year of life: A report of 190 cases. Pediatr Pathol 10:509-526.

- Goldblum JR, Folpe AL (2010) Borderline and malignant fibroblastic/myofibroblastic tumors. Bone Soft Tissue Patho Chapter 3:43-96.

- Knezevich SR, McFadden DE, Tao W, Lim JF, Sorensen PH (1998) A novel ETV6-NTRK3 gene fusion in congenital fibrosarcoma. Nat Genet 18:184-187.

- Eguchi M, Eguchi-Ishimae M, Tojo A, Morishita K, Suzuki K, et al. (1999) Fusion of ETV6 to neurotrophin-3 receptor TRKC in acute myeloid leukemia with t(12;15)(p13;q25) Blood 93:1355-1363.

- Minard-Colin V, Orbach D, Martelli H, Bodemer C (2009) Oberlin O. Soft tissue tumors in neonates. Arch Pediatr 16:1039-1048.

- Dumont C, Monforte M, Flandrin A, Couture A, Tichit R, et al. (2011) Prenatal management of congenital infantile fibrosarcoma: unexpected outcome. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 37:733-735.

- Hashemi A, Tefagh S, Seifadini A, Moghimi M (2013) Infantile Fibrosarcoma in a Child: A Case Report. Iran J Ped Hematol Oncol 3:135-137.

- Kimura C, Kitamura T, Sugihara T (1998) A case of congenital infantile fibrosarcoma of the right hand. J Dermatol 25:735-741.

- Wahid FI, Zada B, Rafique G (2016) Infantile Fibrosarcoma of Tongue: A Rare Tumor. APSP J Case Rep 7:23.

- Pandey A, Kureel SN, Bappavad RP (2016) Chest Wall Infantile Fibrosarcomas -A Rare Presentation. Indian J Surg Oncol 7:127-129.

- Al-Salem AH (2011) Congenital-infantile fibrosarcoma masquerading as sacrococcygeal teratoma. J Pediatr Surg 46:2177-2180.

- Yan AC, Chamlin SL, Liang MG, Hoffman B, Attiyeh EF, et al. (2006) Congenital infantile fibrosarcoma: a masquerader of ulcerated hemangioma. Pediatr Dermatol 23:330-334.

- Gupta A, Sharma S, Mathur S, Yadav DK, Gupta DK (2019) Cervical congenital infantile fibrosarcoma: a case report. Journal of medical Case Reports 13.

- Alias H, Rashid AHA, Lau SCD, Loh CK, Sapuan J, et al. (2019) Early Surgery Is Feasible for a Very Large Congenital Infantile Fibrosarcoma Associated with Life Threatening Coagulopathy: A Case Report and Literature Review. Frontiers in Pediatr 7.

- Tiraje C, Alp O, Hilmi A, Birol H, Sergulen D, et al. (2000 ) Two different clinical presentations of infantile fibrosarcoma. Turk J Cancer 30:81-85.

- Bedmutha A, Singh N, Shivdasani D, Gupta N (2016) Unusual case of infantile fibrosarcoma evaluated on F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography. Indian J Nucl Med 31:201-203.

- Enos T, HoslerGA, Uddin N, Mir A (2017) Congenital infantile fibrosarcoma mimicking a cutaneous vascular lesion: a case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol 44:193-200.

- Ainsworth KE, Chavhan GB, Gupta AA, Hopyan S, Taylor G (2014) Congenital infantile fibrosarcoma: review of imaging features. Pediatr Radiol 44:1124-1129.

- Kihara S, Nehlsen-Cannarella S, Kirsch WM, Chase D, Garvin AJ (1996) A comparative study of apoptosis and cell proliferation in infantile and adult fibrosarcomas. Am J Clin Pathol 106:493-497.

- Orbach D, Brennan B, De Paoli A, Gallego S, Mudry P, et al. (2016) Conservative strategy in infantile fibrosarcoma is possible: The European Paediatric Soft Tissue Sarcoma Study Group experience. Eur J Cancer 57:1-9.

- Blocker S, Koenig J, Ternberg J (1987) Congenital fibrosarcoma. J Pediatr Surg 22:665.

- McCahon E, Sorensen PHB, Davis JH, Rogers PCJ, Schultz KR (2003) Non-resectable congenital tumors with the ETV6-NTRK3 gene fusion are highly responsive to chemotherapy. Med Pediatr Oncol 40:288-292.

- Loh ML, Ahn P, Perez-Atayde AR, Gebhardt MC, Shamberger RC, et al. (2002) Treatment of infantile fibrosarcoma with neoadjuvant chemotherapy: results from the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Children’s Hospital Boston. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 24:722-726.

- Grohn ML, Borzi P, Mackay A, Suppiah R (2004) Management of extensive congenital fibrosarcoma with preoperative chemotherapy. ANZ J Surg 74:919-921.

- Chung EB, Enzinger FM (1976) Infantile fibrosarcoma. Cancer 38:729-739.

- Orbach D, Rey A, Cecchetto G, Oberlin O, Casanova M, et al. (2010) Infantile fibrosarcoma: management based on the European experience. J Clin Oncol 28:318-323.

- Ninane J, Rombouts JJ, Cornu G (1991) Chemotherapy for infantile fibrosarcoma. Med Pediatr Oncol 19:209.

- Shetty AK, Yu LC, Gardner RV, Warrier RP (1999) Role of chemotherapy in the treatment of infantile fibrosarcoma. Med Pediatr Oncol 33:425-427.

-  Salman M, Khoury NJ, Khalifeh I, Abbas HA, Majdalani M, et al (2013) Congenital infantile ï¬brosarcoma: association with bleeding diathesis. Am J Case Rep. 14:481-485.

- Cecchetto G, Carli M, Alaggio R, Dall’Igna P, Bisogno G, et al. (2001) Fibrosarcoma in pediatric patients: results of the Italian Cooperative Group studies (1979-1995). J Surg Oncol 78:225-231.

- Kerl K, Nowacki M, Leuschner I, Masjosthusmann K, Fruhwald MC (2012) Infantile ï¬brosarcoma -an important differential diagnosis of congenital vascular tumors. Pediatr Hematol Oncol 29:545-548.

- Duan S, Zhang X, Wang G, Zhong J, Yang Z, et al. (2013) Primary giant congenital infantile ï¬brosarcoma of the left forearm. Chir Main 32:265-267.

Citation: Awadelkarim ME, Elbahri H (2020) Large Ulcerating Congenital Infantile Fibrosarcoma of the Lower Leg: Case Report and Literature Review. J Orthop Oncol 6: 136. DOI: 10.4172/2472-016X.1000136

Copyright: © 2020 Awadelkarim ME, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 3904

- [From(publication date): 0-2020 - Dec 21, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 2986

- PDF downloads: 918