Molecular Biology Applications in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery.

Received: 01-May-2018 / Accepted Date: 11-May-2018 / Published Date: 17-May-2018

Keywords: Cystic fibrosis; Pharmacogenomics; Maxillofacial surgery; Northern blotting; Periplasmic glucans

Introduction

Genetics is now considered the most acknowledged field in studying human disease causes and considered a rich field in medical researches. Pharmacogenomics is a product of that researches and getting attention to personalize medicine to individuals through investing in the DNA based drug therapy [1,2]. Of all malignancies 1% is mainly caused by single-gene inheritance. Single gene, chromosomal, and multifactorial were used to describe hereditary conditions until the understanding of the interaction between different genes (polygenic inheritance) and including acquired somatic genetic disease category. About 5% of population after age of 25 years will have a disorder with a genetic basis [3].

Genetic Impact on Maxillofacial Surgery: Basic DNA Structure

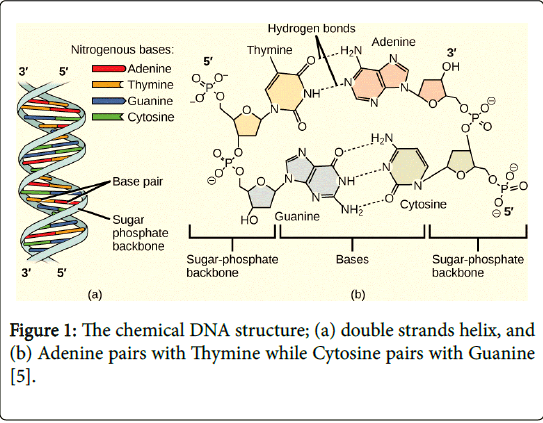

DNA is a long polymer forming a chain of series of nucleotide molecules. Each nucleotide molecules has one molecule of deoxyribose sugar, one molecule of phosphoric acid and one nitrogenous base on the side of the sugar. There are four types of nucleotides in the DNA following the types of nitrogenous bases: Adenine (A), Thymine (T), Cytosine (C) and Guanine (G). The DNA helix model was first suggested by Watson and Crick in which the two polynucleotide chains run besides and opposite to each other. They are attached together by the nitrogen bases through hydrogen bonds with two types. The nitrogen base of the two attached stands of the DNA are paired in a constant arrangement in which Adenine always binds with Thymine and Cytosine always binds with Guanine. This will leads to stable hydrogen bonds between the pairs. The two DNA's stands are complementary twist around forming the double helix (Figure 1). A single turn of the helix is 3.4 nm in length with 10 base pairs and the helix diameter is 2 mm [4].

Figure 1: The chemical DNA structure; (a) double strands helix, and (b) Adenine pairs with Thymine while Cytosine pairs with Guanine [5].

Practical Genetic Methods

DNA sequencing

It was first developed by Walter Gilbert then Frederick Sanger’s on 1975 [6]. It is a process of accurately determining the nucleotide order in a strand of DNA. The initiation of rapid DNA sequencing methods has critically advances the medical researches. A great step proposed by a team of scientists in United State to lead an international program for sequencing the entire human genome in 1988 [7]. In 2000 the team completed the preliminary human DNA sequence of three billion base pairs and in 2004 the complete human DNA sequence was published. In addition they noted that many genes can have multiple functions. The ability to identify the gene that is responsible of an inherited single gene disorder and its diagnostic application will allow better understanding of diseases pathogenesis as well as possible therapeutic applications. This could be achieved through the identification of the human disease candidate gene by the use of animal models of disease or by homology. New disease genes can now be identified using genetic databases [8,9]. During 1980s recombinant DNA techniques allowed mapping through positional cloning which lead to purely identification of the gene by its location without knowing its function [10]. Sequencing technology developed to Exome sequencing which is the analysis of the coding regions of all known genes allowed direct identification of the causal mutation in a family within days to weeks instead of years [11]. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulatory gene (CFTR ) is one of the early identified disease genes during 1980s [12].

Linkage analysis

The adjacent loci on one chromosome are usually inherited together and are called linked alleles. These two close alleles are difficult to be separated during meiosis, crossover or recombination [7]. Linkage analysis was used largely before publication of the complete DNA sequence, development of next generation sequencing methods and microarrays with possibility to analyze multiple million single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) [12].

The Human Genome Project (HGP)

Victor McKusick in 1969 proposed the idea of mapping the human genome. The Human Genome Project concept came in the meeting on 1986 and started in 1991. Its idea is to make a human genome organization which coordinates the individual national genome projects and harbor interaction between genetic scientists [13].

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

PCR facilitates DNA analysis using easily accessible sources such as saliva, buccal smear, blood, and pathological stored tissue. It can be used for detection of gene rearrangement, pathogenic mutation and also for the presence of infectious agent. The evolutionary techniques for analyzing an interesting DNA sequences are DNA sequencing, Southern and Northern blotting, mutation screening, microarray analysis, and real-time PCR. It is therefore resulted in advances in understanding the structure and function of normal gene besides exposing the inherited disease's molecular pathology which offers prenatal diagnosis, presymptomatic diagnosis of genetic diseases and detection of carrier cases that are difficult to detect clinically without symptoms [14-16].

Next-generation sequencing is called a clonal sequencing provided by in vitro cloning using emulsion or bridge PCR to produce large amount of DNA molecules. It lets on concurrent testing of all monogenic disease causative genes having mutations. The specific gene can be targeted by hybridization or gene selected PCR, or by sequencing the entire exome while analyzing only limited genes in single gene [6,13,17]. In infectious diseases, the advancement of molecular biology shifted the conventional laboratory methods that depend on molecular methods providing rapid detection of infectious agents [18]. For example in virology the molecular methods provided ability for genotyping, resistance testing, and quantification of the virus load. In bacteriology in comparison to conventional methods molecular methods provided fast identification of serious bacterial infections, resistance testing, fastidious bacterial infection detection, and bacterial infection identification following antibiotics administration. More improvements are also found in fields of mycology and parasitology leading to fast diagnosis of fungal infection for example in cases of neutropenia. Additional applications of molecular biology involve biosecurity agents' identification, infection control and epidemiology [12,19-27].

Genetic counseling

Genetic counseling is another field in molecular biology that has considerable importance and applications, it has been defined as "The use of genetic counseling to understand and adapt to the medical, psychological, and familial implications of the genetic contributions to disease including:

• Interpretation of family and medical histories to assess the chance of disease occurrence or recurrence.

• Education about inheritance, testing, management, prevention, resources and research.

• Counseling to promote informed choices and adaptation to the risk or condition" [28].

The Table 1 describes the stages of genetic technology development:

| Decade | Development | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| 1980s | Southern blot, Sanger sequencing, and Recombinant DNA technology | DNA sequence of Epstein–Barr virus genome (1984), DNA fingerprinting (1984), and Recombinant erythropoietin (1987). |

| 1990s | Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) | Genetic disorders diagnosis |

| 2000s | Microarray technology and capillary sequencing | Human genome sequence (2003) |

| 2010s | Next-generation sequencing | Human genome sequenced First acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cancer genome sequenced (2008) |

Table 1: Stages of genetic technology development.

Application of Genetics in the Detection, Diagnosis, Pathogenesis, Etiology, Possible Therapeutic and Preventive Methods of Some Maxillofacial Related Conditions

Genetic of cleft lip and palate

Normal palate development is under tight genetic control. The genes that regulate the development of the palate are the sonic hedgehog (SHH), fibro blast growth factors, bone morphogenic proteins and some classes of transforming growth factor β gene [11]. During the palate development the palatal shelves fuse at the midline where the intermingling epithelial cells resorb by apoptosis and the rest of cells transform to mesenchymal cells. But in certain conditions, these cells doesn’t transform as a result of mutations of the genes transforming growth factors B3 which are normally expressed in epithelial cells just before palatal shelves fusion. That will lead to cleft palate [29].

The cleft lip and or palate could be part of a syndrome as a result of single gene disorder or in few situations, as a result of multigene abnormalities. Cleft lip and or palate also might be an isolated defect which is more common. The possible genes related to nonsyndromic clefts are: Blood clotting factor XIII gene (F13A ), endothelin-1 gene and other involved genes. An example of syndromic clefting is Di George Syndrome where its pathogenesis is attributed to failure of neural crest cells to migrate in the areas of 3rd and 4th bracheal arches. It is related to the deletion in the chromosome number 22 and mutation in TBX22 gene [30,31]. Another example is holoprosencephaly syndrome which is caused by mutation in SHH leading to midline defects [9,32,33].

Genetic of MFS syndromes

Several craniofacial disorders and syndromes should maxillofacial manifestations and have genetics behind their pathogenesis:

• Ectodermal dysplasia is a heritable disorder caused by abnormal development of ectodermal tissues including sweat glands, teeth, hair and other related structures. It has features of salivary and lacrimal glands hypoplasia with oral dryness and difficult swallowing, thick lips and prominent forehead. Its genetics related to mutation in EDA, EDAR and EDARADD genes which play an important role in signaling pathway during ectoderm and mesoderm interactions which are critical for the formation of the ectodermal structures [8].

• Mandibulofacial dysostosis or Treacher Collins-Franceschetti syndrome is characterized by hypoplastic zygoma, hypoplastic mandible, downward slanting of the eye. Cleft palate and some cases have absent palatine bone, and auditory structures malformation. It is an inherited autosomal dominant syndrome, related to mutations in Treacher Collins-Franceschetti syndrome 1 (TCOF1 ) gene that is located on long arm of chromosome number 5. This gene encodes a treacle protein that is essential for craniofacial development [29].

• Apert syndrome characterized by premature fusion of coronal suture called craniosynostosis leading to brachycephly and frontal bossing of the skull. Under developed maxilla, cleft palate, hypertelorism, downward slanting of the eyes, syndactyly together with GIT defects and other associated features. It is an autosomal dominant inherited syndrome related to mainly to a substitution mutations in fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 genes located on long arm of chromosome number 10. This will result in increased stimulation of (FGFR2 ) and ossification of bone subperiosteally and leads premature suture union [34].

• Crouzon syndrome or craniofacial dysostosis has some features of apert syndrome with exclusion of syndactyly. It is an autosomal dominant inherited syndrome and can occur as a new mutation without inheritance. It is caused by mutation in FGFR2 gene [35].

• Pfeiffer syndrome is characterized by craniosynostosis, turribrachycephaly, hypertelorism, maxillary hypoplasia, hands and feet are also affected with brachydactyly and syndactyly. It is an autosomal inherited syndrome related to mutations in FGFR1 and FGFR2 genes located on the short arm of chromosome number 8 and long arm of chromosome number 10 respectively [36]. This mutation will cause continuous signaling the bone cells for maturation leading to early fusion of bones affected by the syndrome [11].

Many inherited diseases and syndromes affecting the maxillofacial regions require genetic investigation. Those include metabolic and autoimmune syndromes such as Fabry disease, Williams syndrome, Hurler syndrome, Hunter syndrome, Heerfordt syndrome, Sjogren syndrome [6,15,35,37-40].

Genetics of maxillomandibular occlusion

The malocclusion could be due to mismatch in the sizes of jaws and teeth which are affected by inheritance. Also, could be due to irregular shape of the maxilla and or mandible and the presence of palatal and/or alveolar clefts. Researches revealed that the shapes of craniofacial bones are tightly controlled by genetics [41]. Many genes have been found to contribute to mandibular prognathism [42,43].

With respect to skeletal class II malocclusion pattern, researchers found it to be inherited [44,45]. Both class II and III skeletal malocclusion have been found to have high familial inheritance ability [46]. These findings were confirmed by an Australian twin research on the maxilla and mandible development.

Genetic investigations using linkage analysis to detect the responsible genes and chromosomes for malocclusion

In males with Klinefelter syndrome have significant mandibular prognathism are associated with decrease in cranial base angle while in females with Turner syndrome have retrognathic mandible and increase in cranial base angle. This finding indicated the presence of a relation between X-chromosome and the growth of the cranial base which will affect the facial shape [45,47].

A gene or genes were found responsible about the shape of the maxilla in a study on mice. The genes are located on chromosome number 12 in the mice [48]. With linkage analysis also they suggested that class III malocclusion is related to a gene located on chromosome 1 [36]. A study done on Chinese population found that singlenucleotide polymorphism of the growth hormone receptors gene is related to height of the mandible [49].

Genetic in bone diseases

Benign fibro-osseous Lesion of the Craniofacial Complex: If the polyostotic fibro-osseous lesions that are seen in fibrous dysplasia are presented with endocrinopathy and other disorders then it is called McCune-Albright syndrome (MAS). The genetic alteration is mutation in the G-protein alpha-subunit encoding gene that binds cAMP to hormone receptors [19,27,32,50-54].

A benign fibro-osseous lesion that occurs in association with hyperparathyroidism is ossifying fibroma or hyperparathyroidism-jaw tumor syndrome. In addition to ossifying fibroma of the jaws the syndrome shows other features including Wilms tumors, renal cysts, hamartomas and multiple parathyroid adenomas. Investigations showed that the gene responsible for this syndrome is HRPT2 tumor suppressor gene that maps to chromosome 1q25-q31 and found to be mutated [55]. Disturbances in HRPT2 gene have been found in nonsyndromic ossifying fibromas of the jaws. As a result of linkage analysis methods and shared-haplotype, they reduced the candidate region of this gene to 0.7 cm. [46].

Cytogenetic studies showed deletions in chromosome 2q31-32 q35-36 in a case of cemento-ossifying fibroma of the mandible [23] and chromosomal break points at Xq26 and 2q33 with (X;2) translocations in cases of psammomatoid juvenile ossifying fibroma of the orbit [56].

Osteitis deformans or can be called Paget disease of bone is a form of osseous dysplasia with increased bone turnover in all body bones [20,24,57]. Its genetic mechanism is through a gene called Sequestosome 1 gene (SQSTM1 ) which is a scaffold protein in the NF kappaB pathway resulting in inactivation mutations in TNFRSF11B that encodes osteoprotegerin [13,16,52,58-60].

Cherubism is an autosomal dominant inherited disease [61,62]. The responsible gene is located on chromosome 4p16, which is the adaptor protein 3BP2 location that regulates the high affinity IgE receptor leading to activation of mast cells degranulation [49,63].

In addition to genetic contribution in maxillofacial bone disorders and conditions, genetics is applicable in the prediction of the disease occurrence and diagnosis of diseases that are identical in aspects other than genetics. For example:

• Genetic susceptibility to MRONJ: MRONJ is defined as the presence of an exposed bone in the jaw persisting for more than 8 weeks with no history of radiation therapy while the patient is taking a bisphosphonate or other anti-resorptive drug therapy [64]. Its incidence has been reported to be related to certain Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs). Most of these SNPs are located in genes related to bone turnover, collagen formation, or certain metabolic bone diseases, such as collagen type I alpha1, receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa B (RANK), matrix metallopeptidase 2, osteoprotegerin, and osteopontin [56]. Accordingly, it was suggested that the incidence of MRONJ has a genetic susceptibility [57].

• Distinguishing ossifying fibromas from fibrous dysplasia showed a great challenge to pathologist and clinicians as they share same histopathologic and sometimes radiographic features. Molecular studies now can solve this challenge providing the definitive diagnosis through the identification of Gs-alpha mutations which are found in fibrous dysplasia of the jaws and not in ossifying fibromas [65].

Genetics in significant benign lesions and cysts of the jaws

Odontogenic Keratocyst (OKC) is a developmental odontogenic cyst originated from cell rest of dental lamina and characterized by an aggressive behavior. It is lined by a thin epithelium that has great growth potential, satellite cysts, cords and islands of odentogenic epithelium are usually present in the wall and may contribute to its high recurrence rate. Multiple OKC can be part of a syndrome known as Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (NBCCS) or Gorlin syndrome. It is an autosomal dominant inherited syndrome consists chiefly of OKCs, multiple basal cell carcinomas of the skin, frontal and temporoparietal bossing, hypertelorism, mandibular prognathism, rib and vertebral defects and intracranial calcifications [42,58]. It is caused by mutations in protein patched homolog 1 gene (PTCH1 ) which is a tumor suppressor gene that is mapped to chromosome 9q22.3-31 [44,53]. PTCH1 is considered a receptor for the Drosophila Hedgehog protein thus it controls the Hedgehog signaling pathway that is essential in embryonic cell differentiation and development for the embryo but in adult life it is involved in tumorigenesis such as NBCCS [66,67].

Sonic hedgehog (SHH) pathway has been found to be related to many odontogenic tumors development [50,14,55]. For the pathogenesis of OKC and Ameloblastoma (AB) a study showed activation of SHH pathway through Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) leads to overexpression of upstream genes (PTCH1 and SMO ) and downstream genes (GLI1 , CCND1 and BCL2 ) genes in these two lesions. This finding provided important predictive and therapeutic application for OKC and AB by approaches that can block the SHH pathway before surgical intervention [19,43].

One of the less common benign lesions of the jaws is the central giant cell lesion (CGCL). It was suggested to has a neoplastic source with variable features ranging from mild to locally aggressive, occurs in young age [26,17,25]. A clinically relevant genomic alterations (CRGAs) could be detected by comprehensive genomic profiling (CGP) concurrently with many cancer-related genes.

A high incidence of CRGAs (37.5%) was detected in CGCLs in a pilot study which also showed 25% of somatic mutations that could stimulate the mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway, thus proposing a source of aggressive feature of some CGCLs. Therefore, the presence of mutations is predictive for the lesion aggressiveness and its response to therapy [10].

Another maxillofacial benign tumor is pleomorphic adenoma (PA) of the parotid gland. In a case report of a middle aged female had parotid PA excision then developed PA in the upper lip 6 months later. Multiple chromosomal aberrations was found in the parotid PA using comprehensive genomic hybridization assay, while it was absent in the labial PA. In the parotid PA the assay showed more gains than losses in recognized chromosomal locations [68].

Application of Genetics in Maxillofacial Cancer

Etiology could be genetic and environmental factors. Environmental factors include radiation, chemicals such as arsenical, viruses such as human papilloma virus, and other microorganisms such as Helicobacter pylori . Genes control cells proliferation and those which are related to cancer development called oncogenes which are around 100 in number. There are genes that inhibit tumor growth called tumor suppressor genes. Cancer might occur as a result of mutation on those genes. The cell growth is controlled by signal transduction of the growth factors. Any mutation to the genes that encodes growth factors and growth factor receptors might results in cancer. An example of those oncogenes is mutated ras gene and mutated myc gene. The cell cycle is four phases G1, S, G2 and M. The movement between the phases is controlled by checkpoints and the cell cycle is regulated by cdk/cyclin.

That control of checkpoint will identify any damaged DNA which might be from chemicals or x-rays. One of the monitors at checkpoint in G/S is tumor suppressor gene TP 53 which encodes P 53 protein. P53 level in the cells is normally maintained low. P 53 produced when DNA is damaged and P 53 secreted outside the nucleus to cytoplasm by Mdm2 and then degraded after repair of the DNA. If DNA not repaired the P 53 modified remains in the nucleus leading normally to activation of cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. In case of loss of P 53 no identifier of DNA damage in the cells and cell cycle will escape the checkpoints and leads to tumor formation. From this role P 53 got the name of "guardian of genome". P 53 gene is located in chromosome 17 P13.1 and mutation in TP 53 gene is responsible of 50% of human cancer [69].

Many carcinomas including oral cancers are largely associated with accumulation of genetic mutations. Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is related to multiple molecular genetic aberrations, the most important are DNA copy number aberrations (DCNAs), oncogenes, tumor suppressor genes, mitochondrial mutations, epigenetic changes, microRNAs, genomic instability, and loss of heterozygosity. Using microarray methods the array-based comparative genomic hybridization (A-CGH) provided high-resolution and genome-wide screening of DCNAs. Consequently an extensive analysis of DCNAs in OSCCs became possible by applying A-CGH [5,70-72].

Gene therapy in oral and maxillofacial surgery

Gene defects cause diseases and there are many strategies to treat them. Interventions can be indirect by treating the results of those diseases or direct by treating their causes. This can be attempted by gene defect correction, or gene replacement [73,74]. Steps of gene therapy start with defective gene identification, followed by normal healthy gene cloning, identification of the target tissue, then normal functional gene insertion in the host DNA. Chemical and physical gene transfer can be through DNA microinjection using electroporation, cationic liposome gene transfer, or by using viral vector such as adenoviruses and retroviruses [22,75].

Uses of gene therapy in repair of bone

An example in case of surgical wounds a transfer of gene is applied using adenoviruses vector to transfer bone morphogenic protein gene that encodes BMP-7 into the site of bone defect. This will lead to increase in bone fraction and help large wound healing. This will be temporary in which the host cells increase expression of BMP then generally decrease. A gene has been found to regulate cell differentiation called bone sialoprotein (BSP) is usually expressed during bone regeneration. BSP can be applied at the bone defect site.

NTF-hydrogel can transfer non-viral gene together with hyaluronic acid non-immunogenic gel which will stimulate the cells surrounding the bone defect for repair.

An investigation has been done on rat at site of condyles of the mandible the adeno-associated virus was used to deliver vascular endothelial growth factor resulted in increase in condyles bone and cartilage size [34].

Uses of gene therapy in dental implant

For development of biocompatible dental implants they use of polymers coats that transfer anti apoptotic genes processed by gene activated matrix methods [28].

Uses of gene therapy in salivary glands

They are susceptible to the effect of radiation or immune disease. Their repair can be done by the water channel protein aquaporin-1 encoding gene insertion inside cells of salivary gland ducts which will convert the cells into secretary cells in the gland [75].

Another application is the use of a gene that is synthesizing polypeptide histatin and inserting it into the salivary gland cells leading to increase in saliva production. In case of autoimmune diseases, specific genes activation works as immune modulators and control the autoimmune disease of the salivary glands [76-80].

A gene transfer product

Ex-vivo investigations are done to provide a gene transfer product. They used keratinocytes mixed with retroviruses which can be delivered easily for treatment in oral mucosa or other sites [81].

Uses of gene therapy in head and neck cancer

Researches are directed to provide adenoviruses that are able to multiply and specifically the malignant cells containing mutated P 53 gene [82].

Uses of gene therapy in antibiotic resistant microorganisms

This resistance might be caused by definite genes activation that contributes to glycosyl transferase enzyme synthesis. This enzyme produces periplasmic glucans that provide resistance to antibiotics. Therefore, researchers found that the replication of the mutated definite gene makes the microorganisms susceptible to antibiotics [68].

Uses of gene therapy in host defense

The host defense can be supported by genes encoding antimicrobial protein. It can be supplemented in the host cell at the infection vulnerable sites [47].

Genetic in Special Conditions

There are many inherited diseases commonly occur in families but does not follow the Mendelian inheritance and their occurrence among relatives is low. Those diseases have multifactorial inheritance ranging from mostly environmental to entirely genetic in causation. Examples: Cleft lip and palate, multiple sclerosis, psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, osteogenesis imperfecta. Finding genetic susceptibility in common conditions:

Through twin studies, families share related genetics but also same environment, therefore to identify the susceptibility of a disorder that occur in a family whether it is caused by genetic or environmental is by comparing its frequency between identical and non-identical (dizygotic) twins. By heritability calculation: it gives the proportional contributions of environmental and genetic factors to a trait. It is symbolized as h²

H2=ratio between proportion of a trait of a genetic cause and trait variation in a population

Also the estimation of familial clustering can be calculated by

λ2=ratio between sibling risk of affected individuals and incidence in general population

As per polymorphism association studies, about 10 million Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) have been identified in human genome. These studies provided the possibility to find disease susceptibility loci for many diseases [2,72,83-95].

Genetics in Personalized Medicine

Drugs are shown to be more effective in some individuals than others, in addition, some individuals developed drug side effects more than others. Pharmacogenomics is the study of the interaction between people’s genetic and drug response [96-102]. By the use of genome sequencing, it will be possible to provide personalized pharmacogenomics making optimum drug choice, dose, and estimating side effects [103-114]. Personalized medicine or precision medicine is aiming to provide treatment of a specific disease according to the individual genetic subtype [115-123]. An example of a drug response is malignant hyperthermia with muscle rigidity and raised body temperature occurred rarely as a complication of using halothane anesthesia and succinylcholine for muscle relaxant. Its prediction requires muscle biopsy to test the reaction with the anesthesia. The most likely cause is mutation in ryanodine receptor gene (RYR1 ).

References

- Glodstein DB, Tate SK, Sisodiya SM (2003) Pharmacogenetics goes genomic. Nat Rev Genet 4: 937-947.

- William N, Katherine P (2008) Removing barriers to a clinical pharmacogenetics service. Pers Med 5: 471-480.

- Albert FW, Kruglyak L (2015) The role of regulatory variation in complex traits and disease. Nature Rev Genet 16:197-212.

- Watson JD, Crick FH (1953) Molecular structure of nucleic acids. Nature 171: 737-738.

- Voulgarelis M, Tzioufas AG (2010) Current aspects of pathogenesis in Sjogren’s syndrome. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis 2: 325-334.

- Ruggiero SL, Dodson TB, Fantasia J, Goodday R, Aghaloo T, et al. (2014) American association of oral and maxillofacial surgeons position paper on medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw-2014 update. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 72: 1938-1956.

- Aartsma A, Ommen GJ (2010) Progress in therapeutic antisense applications for neuromuscular disorders. Eur J Hum Genet 18: 146-153.

- Chong B, Hegde M, Fawkner M, Simonet S, Cassinelli H, et al. (2003) Idiopathic hyperphosphatasia and TNFRSF11B mutations: Relationships between phenotype and genotype. J Bone Miner Res 18: 2095-2104.

- Maiden MC, Bygraves JA, Feil E, Morelli G, Russell JE, et al. (1998) Multilocus sequence typing: A portable approach to the identification of clones within populations of pathogenic microorganisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci 95: 3140-3145.

- Qu J, Yu F, Hong Y, Guo Y, Sun L, et al. (2015) Underestimated PTCH1 mutation rate in sporadic keratocystic odontogenic tumors. Oral oncol 51: 40-45.

- Meng XM, Yu SF, Yu GY (2005) Clinicopathologic study of 24 cases of cherubism. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 34: 350-356.

- Nakasima A, Ichinose M, Nakata S, Takahama Y (1982) Hereditary factors in the craniofacial morphology of Angle's Class II and Class III malocclusions. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 82: 150-156.

- Lopez Rangel E, Maurice M, McGillivray B, Friedman JM (1992) Williams syndrome in adults. Am J Med Genet A 44: 720-729.

- Dal P, Sciot R, Fossion E, Van Damme B, Berghe H (1993) Chromosome abnormalities in cementifying fibroma. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 71: 170-172.

- Cohen Jr MM (2010) Hedgehog signaling update. Am J Med Genet A 152: 1875-1914.

- Speers DJ (2006) Clinical applications of molecular biology for infectious diseases. Clin Biochem Rev 27: 39.

- de Sanctis L, Delmastro L, Russo MC, Matarazzo P, Lala R, et al. (2006) Genetics of McCune-Albright syndrome. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 19: 577-582.

- Allyse M, Minear MA, Berson E, Sridhar S, Rote M, et al. (2015) Non-invasive prenatal testing: A review of international implementation and challenges. Int J Womens Health Wellness 7: 113.

- Daroszewska A, Ralston SH (2005) Genetics of Paget's disease of bone. Clin Sci 109: 257-263.

- de Lange J, Akker HP (2005) Clinical and radiological features of central giant-cell lesions of the jaw. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 99: 464-470.

- de Lange J, van den Akker HP, van den Berg H (2007) Central giant cell granuloma of the jaw: A review of the literature with emphasis on therapy options. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 104: 603-615.

- Yang S, Rothman RE (2004) PCR-based diagnostics for infectious diseases: Uses, limitations, and future applications in acute-care settings. Lancet Infect Dis 4: 337-348.

- Cockerill FR, Smith TF (2004) Response of the clinical microbiology laboratory to emerging (new) and reemerging infectious diseases. J Clin Microbiol 42: 2359-2365.

- Kim KM, Rhee Y, Kwon YD, Kwon TG, Lee JK, et al. (2015) Medication related osteonecrosis of the jaw: 2015 position statement of the Korean Society for Bone and Mineral Research and the Korean Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. J Bone Metab 22: 151-165.

- Fredricks DN, Relman DA (1999) Application of polymerase chain reaction to the diagnosis of infectious diseases. Clin Infect Dis 1: 475-486.

- Ng SB, Buckingham KJ, Lee C, Bigham AW, Tabor HK, et al. (2010) Exome sequencing identifies the cause of a Mendelian disorder. Nature genetics. 42: 30-35.

- T Strachan, AP Read (1996) Human molecular genetics. Ann Hum Genet 61: 283-285.

- Murray JC (1995) Face facts: Genes, environment, and clefts. Am J Hum Genet 57: 227-232.

- Reddy SV (2006) Etiologic factors in Paget’s disease of bone. Cell Mol Life Sci 63: 391-398.

- Harris JE (1975) Genetic factors in the growth of the head. Inheritance of the craniofacial complex and malocclusion. Dent Clin North Am 19: 151-160.

- Janssens K, de Vernejoul MC, de Freitas F, Vanhoenacker F, Van Hul W (2005) An intermediate form of juvenile Paget's disease caused by a truncating TNFRSF11B mutation. Bone 36: 542-548.

- Kraus BS, Wise WJ, Frei RH (1959) Heredity and the craniofacial complex. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 45: 172-217.

- Whyte MP, Hughes AE (2002) Expansile skeletal hyperphosphatasia is caused by a 15 base pair tandem duplication in TNFRSF11A encoding RANK and is allelic to familial expansile osteolysis. J Bone Miner Res 17: 26-29.

- Peltomaki T, Alvesalo L, Isotupa K (1989) Shape of the craniofacial complex in 45, X females: Cephalometric study. J Craniofac Genet Dev Biol 9: 331-338.

- Francke U (1999) Williams-Beuren syndrome: Genes and mechanisms. Hum Mol Gen 8: 1947-1954.

- Baldwin C, Garnis C, Zhang L, Rosin MP, Lam WL (2005) Multiple microalterations detected at high frequency in oral cancer. Cancer Res 65: 7561-7567.

- Gorlin RJ (1987) Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. Neurocutaneous Diseases 7: 67-79.

- Cavey JR, Ralston SH, Sheppard PW, Ciani B, Gallagher TR, et al. (2006) Loss of ubiquitin binding is a unifying mechanism by which mutations of SQSTM1 cause Paget’s disease of bone. Calcif Tissue Int 78: 271-277.

- Tiziani V, Reichenberger E, Buzzo CL, Niazi S, Fukai N, et al. (1999) The gene for cherubism maps to chromosome 4p16. Am J Hum Genet 65: 158-166.

- Pinkel D, Albertson DG (2005) Comparative genomic hybridization. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet 6: 331-354.

- Frazier-Bowers S, Rincon-Rodriguez R, Zhou J, Alexander K, Lange E (2009) Evidence of linkage in a Hispanic cohort with a Class III dentofacial phenotype. J Dent Res 88: 56-60.

- Shillitoe EJ, Chen Z, Kamath P, Zhang S (1994) Anti-papilloma virus ribozymes for gene therapy of oral cancer. Head Neck 16: 506.

- Baird PA, Anderson TW, Newcombe HB, Lowry RB (1988) Genetic disorders in children and young adults: A population study. Am J Hum Genet 42: 677.

- Kalfa N, Philibert P, Audran F, Ecochard A, Hannon T, et al. (2006) Searching for somatic mutations in McCune-Albright syndrome: A comparative study of the peptidic nucleic acid versus the nested PCR method based on 148 DNA samples. Eur J Endocrinol 155: 839-843.

- Lindsay EA, Vitelli F, Su H, Morishima M, Huynh T, et al. (2001) Tbx1 haploinsufficiency in the DiGeorge syndrome region causes aortic arch defects in mice. Nature 410: 97-101.

- Kimonis VE, Goldstein AM, Pastakia B, Yang ML, Kase R, et al. (1997) Clinical manifestations in 105 persons with nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. Am J Med Genet 69: 299-308.

- Zhou J, Lu Y, Gao XH, Chen YC, Lu JJ, et al. (2005) The growth hormone receptor gene is associated with mandibular height in a Chinese population. J Dent Res 84: 1052-1056.

- Uchida K, Oga A, Nakao M, Mano T, Mihara M, et al. (2011) Loss of 3p26. 3 is an independent prognostic factor in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol Rep 26: 463-469.

- Lannon DA, Earley MJ (2001). Cherubism and its charlatans. Br J Plast Surg 54: 708-711.

- ENCODE Project Consortium (2012) An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature 489: 57-74.

- Elles R, Mountford R (2003) Molecular diagnosis of genetic diseases. Springer Science & Business Media.

- Basic V, Cesarik M, Zavoreo I, Madzar Z, Demarin V (2012) Anderson-Fabry disease: Developments in diagnosis and treatment. Acta Clin Croat 51: 411-417.

- Sanger F, Coulson AR (1975) A rapid method for determining sequences in DNA by primed synthesis with DNA polymerase. J Mol Biol 94: 441-448.

- Baum BJ, Kok M, Tran SD, Yamano S (2002) The impact of gene therapy on dentistry: a revisiting after six years. J Am Dent Associat 133: 35-44.

- Louie L, Goodfellow J, Mathieu P, Glatt A, Louie M, et al. (2002) Rapid detection of methicillin-resistant staphylococci from blood culture bottles by using a multiplex PCR assay. J Clin Microbiol 40: 2786-2790.

- Witte JS, Visscher PM, Wray NR (2014) The contribution of genetic variants to disease depends on the ruler. Nature Rev Genet 15: 765-776.

- Toyosawa S, Yuki M, Kishino M, Ogawa Y, Ueda T, et al. (2007) Ossifying fibroma vs fibrous dysplasia of the jaw: Molecular and immunological characterization. Modern Pathol 20: 389-396.

- AlexaW, Brian E, George N (1993) Dna & indigeneity. DNA and Indigeneity 22: 2.

- Mulligan RC (1993) The basic science of gene therapy. Science 260: 926-932.

- Eversole R, Su L, ElMofty S (2008) Benign fibro-osseous lesions of the craniofacial complex a review. Head Neck Pathol 2: 177-202.

- Rutland P, Pulleyn LJ, Reardon W, Baraitser M, Hayward R, et al. (1995) Identical mutations in the FGFR2 gene cause both Pfeiffer and Crouzon syndrome phenotypes. Nature genet 9: 173-176.

- Lietman SA, Ding C, Levine MA (2005) A highly sensitive polymerase chain reaction method detects activating mutations of the GNAS gene in peripheral blood cells in McCune-Albright syndrome or isolated fibrous dysplasia. J Bone Joint Surg 87: 2489-2494.

- Scambler PJ (2000) The 22q11 deletion syndromes. Hum Mol Gen 9: 2421-2426.

- Oh J, Wang CJ, Poole M, Kim E, Davis RC, et al. (2007) A genome segment on mouse chromosome 12 determines maxillary growth. J Dent Res 86: 1203-1206.

- Royer-Pokora B, Kunkel LM, Monaco AP, Goff SC, Newburger PE, et al. (1986) Cloning the gene for an inherited human disorder-Chronic granulomatous disease-on the basis of its chromosomal location. Nature 322: 32-38.

- Bayes M, Hartung AJ, Ezer S, Pispa J, Thesleff I, et al. (1998) The anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia gene (EDA) undergoes alternative splicing and encodes ectodysplasin-A with deletion mutations in collagenous repeats. Human Mol Genet 7: 1661-1669.

- Gagnon A, Wilson RD, Allen VM, Audibert F, Blight C, et al. (2009) Evaluation of prenatally diagnosed structural congenital anomalies. J Obstet Gynaecol 31: 875-881.

- Chr S, Meadow W (1965) For progeny inheritance: Advances of orthodontist. J Orofac Orthop 26: 213-229.

- Gurgel CA, Buim ME, Carvalho KC, Sales CB, Reis MG, et al. (2014) Transcriptional profiles of SHH pathway genes in keratocystic odontogenic tumor and ameloblastoma. J Oral Pathol Med 43: 619-626.

- Lumbroso S, Paris F, Sultan C (2004) Activating Gsα mutations: Analysis of 113 patients with signs of McCune-Albright syndrome-A European Collaborative Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89: 2107-2113.

- Mastrangeli A, O'Connell BR, Aladib WA, Fox PC, Baum BJ, et al. (1994) Direct in vivo adenovirus-mediated gene transfer to salivary glands. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 266: G1146-G1155.

- Belloni E, Muenke M, Roessler E, Traverse G, Siegel-Bartelt J, et al. (1996) Identification of Sonic hedgehog as a candidate gene responsible for holoprosencephaly. Nature genet 14: 353-356.

- Bezak B, Lehrke H, Elvin J, Gay L, Schembri-Wismayer D, et al. (2017) Comprehensive genomic profiling of central giant cell lesions identifies clinically relevant genomic alterations. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 75: 955-961.

- Carlson BM (2012) Human embryology and developmental biology E-book: With Student Consult Online Access. Elsevier Health Sciences.

- Carrol ED, Thomson AP, Riordan FA, Fellick JM, Shears P, et al. (2000) Increasing microbiological confirmation and changing epidemiology of meningococcal disease on Merseyside, England. Clin Microbiol Infect 6: 259-262.

- Chari NS, McDonnell TJ (2007) The sonic hedgehog signaling network in development and neoplasia. Adv Anatom Pathol 14: 344-352.

- Chinawa JM, Adimora GN, Obu HA, Tagbo B, Ujunwa F, et al. (2012) Clinical presentation of mucopolysaccharidosis type II (Hunter’s syndrome). Ann Med Health Sci Res 2: 87-90.

- Chuong R, Kaban LB, Kozakewich H, Perez-Atayde A (1986) Central giant cell lesions of the jaws: A clinicopathologic study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 44: 708-713.

- Katz J, Gong Y, Salmasinia D, Hou W, Burkley B, et al. (2011) Genetic polymorphisms and other risk factors associated with bisphosphonate induced osteonecrosis of the jaw. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 40: 605-611.

- Weinstein LS, Liu J, Sakamoto A, Xie T, Chen M (2004) Minireview: GNAS: Normal and abnormal functions. Endocrinol 145: 5459-5464.

- Collet C, Michou L, Audran M, Chasseigneaux S, Hilliquin P, et al. (2007) Paget's disease of bone in the French population: Novel SQSTM1 mutations, functional analysis, and genotype-phenotype correlations. J Bone Miner Res 22: 310-317.

- Cornetta K, Morgan RA, Anderson WF (1991) Safety issues related to retroviral-mediated gene transfer in humans. Human Gene Ther 2: 5-14.

- Dunn CA, Jin Q, Taba Jr M, Franceschi RT, Rutherford RB, et al. (2005) BMP gene delivery for alveolar bone engineering at dental implant defects. Mol Ther 11: 294-299.

- Edwards SJ, Gladwin AJ, Dixon MJ (1997) The mutational spectrum in Treacher Collins syndrome reveals a predominance of mutations that create a premature-termination codon. Am J Human Genet 60: 515-524.

- Fitzgerald TW, Gerety SS, Jones WD, Van Kogelenberg M, King DA, et al. (2015) Large-scale discovery of novel genetic causes of developmental disorders. Nature 519: 223-228.

- Franceschi RT, Wang D, Krebsbach PH, Rutherford RB (2000) Gene therapy for bone formation: In vitro and in vivo osteogenic activity of an adenovirus expressing BMP7. J Cellular Biochem 78: 476-486

- Gilbert GL, James GS, Sintchenko V (1999) Culture shock. Molecular methods for diagnosis of infectious diseases. Med J Aust 171: 536-539.

- Giugliani R, Federhen A, Munoz Rojas MV, Vieira T, Artigalas O, et al. (2010) Mucopolysaccharidosis I, II, and VI: Brief review and guidelines for treatment. Genet Mol Biol 33: 589-604.

- Hahn H, Wicking C, Zaphiropoulos PG, Gailani MR, Shanley S, et al. (1996) Mutations of the human homolog of Drosophila patched in the nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. Cell 85: 841-851.

- Hobbs MR, Pole AR, Pidwirny GN, Rosen IB, Zarbo RJ, et al. (1999) Hyperparathyroidism-jaw tumor syndrome: The HRPT2 locus is within a 0.7 cm region on chromosome 1q. Am J Human Genet 64: 518-525.

- Huang GT, Zhang HB, Kim D, Liu L, Ganz T (2002) A model for antimicrobial gene therapy: Demonstration of human β-defensin 2 antimicrobial activities in vivo. Human Gene Ther 13: 2017-2025.

- Iannuzzi MC, Rybicki BA (2007) Genetics of sarcoidosis: Candidate genes and genome scans. Proc Am Thorac Soc 4: 108-116.

- Imai Y, Kanno K, Moriya T, Kayano S, Seino H, e al. (2003) A missense mutation in the SH3BP2 gene on chromosome 4p16. 3 found in a case of nonfamilial cherubism. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 40: 632-638.

- Ingham PW, McMahon AP (2001) Hedgehog signaling in animal development: Paradigms and principles. Genes Dev 15: 3059-3087.

- Ivnitski D, O Neil DJ, Gattuso A, Schlicht R, Calidonna M, et al. (2003) Nucleic acid approaches for detection and identification of biological warfare and infectious disease agents. Biotechniques 35: 862-869.

- Johnson RL, Rothman AL, Xie J, Goodrich LV, Bare JW, et al. (1996) Human homolog of patched, a candidate gene for the basal cell nevus syndrome. Science 272: 1668-1671.

- Katoh Y, Katoh M (2009) Hedgehog target genes: Mechanisms of carcinogenesis induced by aberrant hedgehog signaling activation. Current molecular medicine 9: 873-886.

- Lajeunie E, Ma HW, Bonaventure J, Munnich A, Le Merrer M, et al. (1995) FGFR2 mutations in Pfeiffer syndrome. Nature genetics 9: 108-108.

- Litton SF, Ackermann LV, Isaacson RJ, Shapiro BL (1970) A genetic study of Class III malocclusion. Am J Orthodon Dentofac Orthoped 58: 565-577.

- Mah TF, Pitts B, Pellock B, Walker GC, Stewart PS, et al. (2003) A genetic basis for Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm antibiotic resistance. Nature 426: 306-310.

- Marsh KL, Dixon J, Dixon MJ (1998) Mutations in the Treacher Collins syndrome gene lead to mislocalization of the nucleolar protein treacle. Human Mol Genet 7: 1795-1800.

- McCarthy MI, Abecasis GR, Cardon LR, Goldstein DB, Little J, et al. (2008) Genome-wide association studies for complex traits: consensus, uncertainty and challenges. Nature Rev Genet 9: 356-369.

- McKusick VA (1998) Mendelian inheritance in man: A catalog of human genes and genetic disorders. JHU Press.

- BC O’Connell, A Mastrangeli, FG Oppenheim, RG Crystal, BJ Baum (1993) Adenovirus mediated gene transfer ofhistatin 3 to rat salivary glands in vivo. J Dent Res, 73: 310.

- Perdigao PF, Pimenta FJ, Castro WH, De Marco L, Gomez RS (2004) Investigation of the GSα gene in the diagnosis of fibrous dysplasia. International journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery 33: 498-501.

- Peruski LF, Peruski AH (2003) Rapid diagnostic assays in the genomic biology era: Detection and identification of infectious disease and biological weapon agents. Biotechniques. 35: 840-849.

- Proetzel G, Pawlowski SA, Wiles MV, Yin M, Boivin GP, et al. (1995) Transforming growth factor-β3 is required for secondary palate fusion. Nature genetics 11: 409.

- Resta R, Biesecker BB, Bennett RL, Blum S, Hahn SE, et al. (2006) A new definition of genetic counseling: National Society of Genetic Counselors’ task force report. J Genet Counsel 15: 77-83.

- Sawyer JR, Tryka AF, Bell JM, Boop FA (1995) Nonrandom chromosome breakpoints at Xq26 and 2q33 characterize cement-ossifying fibromas of the orbit. Cancer 76: 1853-1859.

- Snijders AM, Schmidt BL, Fridlyand J, Dekker N, Pinkel D, et al. (2005) Rare amplicons implicate frequent deregulation of cell fate specification pathways in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oncogene 24: 4232.

- Southorn B, Manor E, Bodner L, Spedding AV, Brennan PA (2013) Metachronous pleomorphic adenomas occurring in the parotid and a minor salivary gland with genetic changes detected by comparative genomic hybridization. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 71: 805-808.

- Stone DM, Hynes M, Armanini M, Swanson TA, Gu Q, et al. (1996) The tumour-suppressor gene patched encodes a candidate receptor for Sonic hedgehog. Nature 384: 129.

- Szabo J, Heath B, Hill VM, Jackson CE, Zarbo RJ, et al. (1995) Hereditary hyperparathyroidism-jaw tumor syndrome: The endocrine tumor gene HRPT2 maps to chromosome 1q21-q31. Am J Human Genet 56: 944.

- Taichman LB (1993) Keratinocyte gene therapy: Using genetically altered keratinocytes to deliver new gene products. Dermatology: Progress and perspectives. Pearl River, NY: Parthenon 53-56.

- Tarasevich IV, Shaginyan IA, Mediannikov OY (2003) Problems and perspectives of molecular epidemiology of infectious diseases. Ann N Y Acad Sci 990: 751-756.

- Toftgard R (2000) Hedgehog signalling in cancer. Cell Mol Life Sci 57: 1720-1731.

- James D Watson (1968) The double helix: Being a personal account of the discovery of the structure of dna. New York, Atheneum 159: 1448-1449.

- Whyte MP (2006) Paget's Disease of Bone and Genetic Disorders of RANKL/OPG/RANK/NF-κB Signaling. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1068: 143-164.

- Wilkie AO, Slaney SF, Oldridge M, Poole MD, Ashworth GJ, et al. (1995) Apert syndrome results from localized mutations of FGFR2 and is allelic with Crouzon syndrome. Nature genetics 9: 165-172.

- Yip KH, Feng H, Pavlos NJ, Zheng MH, Xu J (2006) p62 ubiquitin binding-associated domain mediated the receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand-induced osteoclast formation: A new insight into the pathogenesis of Paget's disease of bone. Am J Pathol 169: 503-514.

Citation: Al-Eid R (2018) Molecular Biology Applications in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. Cosmetol & Oro Facial Surg 4: 131.

Copyright: © 2018 Al-Eid R. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Open Access Journals

Article Usage

- Total views: 11248

- [From(publication date): 0-2018 - Dec 22, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 9957

- PDF downloads: 1291