Paediatric Advance Life Support (PALS)

Received: 02-Oct-2023 / Manuscript No. tpctj-23-116314 / Editor assigned: 06-Sep-2023 / PreQC No. tpctj-23-116314(PQ) / Reviewed: 20-Oct-2023 / QC No. tpctj-23-116314(QC) / Revised: 27-Oct-2023 / Manuscript No. tpctj-23-116314(R) / Accepted Date: 31-Oct-2023 / Published Date: 31-Oct-2023 DOI: 10.4172/tpctj.1000209

Readers should be able to:

1. Distinguish between the components of a pediatric assessment.

2. Describe techniques for childhood assessment.

3. Explain the components of the pediatric evaluation triangle and why you formed a broad impression of the patient.

4. Summarize the purpose and components of the primary assessment.

5. Identify normal age group related vital signs.

6. Discuss the benefits of pulse oximetry and capnometry or capnography during patient assess- ment.

7. Make the distinction between central and peripheral pulses.

8. Summarize the purpose and components of the secondary assessment.

9. Discuss how to obtain a patient history using the SAMPLE mnemonic.

10. Describe the diagnostic test and lab results.

11. Recognize the value of collaboration during a resuscitation effort.

12. While working as the team leader of a resuscitation effort, discuss the key roles of team members.

Introduction

A methodical strategy to assessing an unwell or ill child is required, as is knowledge of growth and de- velopmental pathways, as well as a comprehension of the anatomic and physiologic variations between children and adults. Obtaining historical information and doing a physical examination differ based on the child’s age and appearance [1]. Patient care is delivered by a team of professionals regardless of the healthcare environment in which you work.

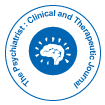

Rapid assessment: pediatric assessment triangle

When dealing with emergency situations, it is critical to do a quick visual examination of children and in- fants before gathering data and administering assistance. This visual assessment allows you to ensure that the surroundings is safe and to evaluate if the situation is life-threatening and requires immediate inter- vention. The Pediatric Assessment Triangle (PAT), which employs an A-B-C strategy (Appearance, Work of Breathing, Circulation) during the initial assessment, is considered as the cornerstone of emergency case assessment and care.

Appearance

The first step in PAT is to analyze the patient’s appearance and attentiveness (if the child or infant is inter- acting with the environment, parents, and caregiver, if he crying or speaking, and if he looks lethargic of flaccid, limps, or has poor muscle tone).

Work of Breathing

The patient’s work of breathing is evaluated in the second step of PAT by:

1. Observing any signs of increased respiratory efforts like using of accessory muscles, nasal flaing, and retractions.

2. Listening to any audible breath sounds such as wheezing, stridor, or grunting).

3. Respiratory rate (rapid, slow, or apneic).

Circulation

The last assessment part of PAT is the circulation. in this part, the healthcare provider will observe the signs of inadequate perfusion, mostly assess the mucus membranes and skin color (Flushing, Cyanosis, Pallor, or Mottling).

Pediatric resuscitation

Use the shout-tap-shout process to see if the patient is responsive. For a child, tap the shoulder, and for an infant, tap the bottom of the foot.

If the patient not responding:

1. Activate emergency mobile services (EMS), the rapid response team (RRT), or the Code team, and request a cardiac monitor, defibrillator, or automated external defibrillator (AED) .

2. Open airway using head tilt chin lift technique or jaw thrust technique.

3. Check pulse and breathing simultaneously (carotid for children; brachial for infants) for at least 5 seconds, but no more than 10.

4. If patient is pulseless and apneic, start basic life support.

5. If the patient is breathing and has a pulse, proceed to primary and secondary examination, of- fer care as needed, and monitor and notice any changes while waiting for the resuscitation team

6. If the patient is apneic but still has a pulse, give bag-mask ventilation (BMV) and check the pulse every 2 minutes.

Primary assessment

Complete a primary assessment after the rapid assessment has been completed and you have determined that the patient is not experiencing a life-threatening emergency. This includes gathering physical and physiological data to help identify the underlying cause(s) of the patient’s emergency condition [2].

The primary assessment’s purpose is to identify potentially lifethreatening conditions and correct them as soon as possible to keep the patient’s condition from worsening. The primary assessment processes should be repeated until the patient is stabilized, transferred to a higher level of care, or both. Once Sequence for the Primary Assessment the Primary Assessment Sequence the A-B-C-D-E mnemonic is used in the primary assessment to emphasize the strategy to evaluating the kid or infant.

Airway: Determine the patency of the patient’s upper airway.

You will notice normal breathing and breath noises in the patient if the airway is patent. The following in- dications may be present if the airway is not patent: Respiratory discomfort or increased work of breathing (i .e., nasal flaring, use of accessory muscles, intercostal or suprasternal retractions) Stridor, grunting, and wheezing are all examples of abnormal breath noises. Patency must be restored and maintained immedi- ately if the patient’s airway is not open and clear. Simple interventions include moving the patient or conducting manual procedures to open the airway (e.g., head-tilt/chin-lift technique or modified jaw-thrust maneuver) can keep an occluded but sustainable airway open manually.

It is also critical to clear the airway by suctioning or removing any apparent foreign materials (do not do a blind finger sweep). To keep the airway open, a basic airway (oropharyngeal or nasopharyngeal airway) may be essential. When an airway is clogged and cannot be maintained with manual maneuvers, suctioning, or a basic air- way, CPAP, noninvasive ventilation, or an advanced airway must be used. If the child’s or infant’s airway is clogged and you suspect a foreign body is to blame, take the following steps: Encourage coughing to clear The airway if the child or newborn is choking but can cough, speaks, cry, or breathe (Figure 1).

Breathing: Examine the patient’s breathing to see if ventilation and oxygenation are adequate. In order to evaluate a child’s or infant’s respiration, look for:

Breathing rate, depth, and rhythm: Is the patient breathing slowly or quickly? Is it usual to have chest and abdominal movements?

Is the beat regular or irregular? Take note of the chest expansion and air movement. Is there an increase in work of breathing, such as nasal flaring, auxiliary muscle usage, and intercostal or suprasternal retractions?

Listen for breath sounds: Have you heard sounds like wheezing, grunting, stridor, gurgling, or crackling? Changes in voice or cry: Are there any changes in voice or cry (e.g., hoarseness, hot potato voice)?

Oxygen saturation: What is the patient’s oxygen saturation based on a pulse oximeter reading?

Supplemental oxygen should be given as needed to maintain an oxygen saturation of more than 94%. Support breathing if necessary by using a bag valve-mask (BVM) resuscitator to administer ventilations. If necessary, use noninvasive or invasive ventilation (Table 1).

| Age Group | Respiratory Rate (Breaths per Minute) | Awake Heart Rate (Beats per Minute) | Systolic Blood Pressure mmHg | Diastolic Blood Pressure mmHg |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newborn | 30-60 | 100-200 | 60-85 | 35-55 |

| Infant (1 to 12 months) |

30-50 | 100-180 | 70-100 | 35-60 |

| Toddler (1 to 2 years) |

24-40 | 90-140 | 85-105 | 40-65 |

| Preschooler (3 to 5 years) | 20-30 | 80-130 | 89-115 | 45-70 |

| School Age (6 to 12 years) | 16-26 | 70-120 | 94-120 | 55-80 |

| Adolescent (13 to 17 years) | 12-20 | 60-100 | 110-135 | 60-85 |

| Quick Assessment for Hypotension | Quick Assessment for Hypoglycemia | |

|---|---|---|

| Age Group | Systolic Blood Pressure mmHg | Plasma glucose threshold: • Neonates: < 45 mg/dL Infants, children and adolescents: < 60 mg/dL |

| Neonate | < 60 | |

| Infant | < 70 | |

| Toddler to School Age | < 70 + (age in years x 2) | |

| Adolescent | < 90 | |

Table 1:Normal vital signs by age groups.

Circulation: Check for adequate perfusion. Reduced perfusion can result in decreased oxygenation (hypoxia) of tissues and essential organs, as well as a reduction in nutrition supply. Checking the following things can help you assess the patient’s circulation:

Peripheral pulses: Pulses, both central and peripheral: Is it possible to feel the pulses? Are they strong and thready or weak and thready? Are there significant differences in the properties of central and peripheral pulses?

Blood pressure (BP) levels

Is there a drop in blood pressure (hypotension)? Rhythm and heart rate: Is your heart rate faster than usual (tachycardia)? Is your heart rate slowing down (bradycardia)? Is there an abnormal ECG rhythm during cardiac monitoring?

Is the patient’s skin and mucous membranes pale (or gray/dusky), mottled, or cyanotic (centrally and/or peripherally)? Is the color of the mucous membranes pink or pale?

Skin temperature

In a normothermia atmosphere, does the skin feel chilly to the touch? Is the capillary refill time excessive (more than 2 seconds)?

As needed, provide supportive care. Establish intravenous, intraosseous, or both intravenous and intraosseous access for the delivery of fluids, medicines, or both (Figure 2).

Disability

Quickly assess the neurological status of the child or infant during the disability evaluation. Is there a drop in level of consciousness? Is the patient perplexed? Is the patient becoming increasingly agitated or diffi- cult to awaken? Is there any seizure activity?

PERRL Pupillary Response (Pupils Equal, Round, Reactive to Light). Are the pupils well- defined? Dilated? Is the patient hypoglycemic, resulting in a change in level of consciousness?

The AVPU scale is as follows:

Awake: The patient is awake and engaged.

Patient solely reacts to verbal commands and does not respond to voice stimulation (e.g. shout- ing their name, talking or yelling).

Only painful stimuli can elicit a response from the patient (e.g. pinching the trapezius area or performing a sternalrub).

Unresponsive: The patient is unresponsive to all stimuli. During

Exposure: Check the patient’s body for visible symptoms of injury or disease, and take note of skin color and tem- perature as the final phase of the primary evaluation. If not already done/available, remove clothing as needed to assess the head, ears, face, and neck; the anterior and posterior trunk; and the upper and lower extremities; and body temperature.

Secondary assessment

When performing the secondary assessment, complete a more indepth history and perform a head- to-toe examination to identify any problems that were not identified during the primary assessment. The acronym ‘SAMPLE’ may be useful during history taking.

History taking (sample)

Adult and pediatric history taking are not the same and provide different obstacles. A parent or guardian frequently reports symptoms since they are unable to provide an accurate history of the child’s illness and worries. To bridge the gaps, excellent communication skills and strategies to develop a collaborative style to interact with children and their families are fundamental elements while taking history. Additionally, it is essential to devote particular attention to growth and developmental issues characteristic typical in childhood and be cognizant of the differences in disease presentation between children and adults.

Head to toe examination

The physical examination should be detailed and focused on the symptoms of the patient. The detailed physical examination is aimed at inspecting all parts of the body for deformities, ecchymosis, lacerations and abrasions, punctures and penetrating wounds, in addition to any tenderness, edema, or burns. If pos- sible, try to examine painful areas last and try to avoid moving the affected areas.

Based on the patient’s appearance, chief complaint, primary assessment findings, and the severity of the child’s sickness or injury, a specialized physical examination may be more suitable. Compare one side of the body to the other throughout the examination. Use the unaffected side as the typical finding for com- parison if a sickness or accident affects one side of the body (Table 2).

| History Focus Areas | Information to Gather |

|---|---|

| Signs and symptoms | Altered consciousness, respiratory difficulties, vomiting, diarrhea, fever, bleed- ing episodes |

| Allergies | Environmental, food, and medication |

| Medications | Recent drugs (including dosage and administration time) and any recent medication changes |

| Past medical/surgical history | Birth history, Immunization history Medical or surgical history |

| Last meal | Meal type and time of intake |

| Events | Time of onset Description of the symptoms leading to the current episode Treatments already administered |

Table 2: History taking using the mnemonic SAMPLE.

Head and neck

Inspect the skull and face and observe for symmetry and balance.

Evaluate the patient’s of motion range

Assess the kid’s head control and neck strength; the whole range of motion can be determined by asking the older child to move their head up and down and turn their head right and left as far as possible; the examiner should gently move the head of the infant to check for any signs of neck stiffness.

Assess the fontanels: The examiner uses the flat pads of their fingers to gently feel the head surface to determine the fontanels (open or closed). Additionally, they should check for any retraction or bulging of the fontanel.

Assess the eyes: It is essential to observe the eyes for symmetry and their position with respect to the nose. Examine the eyes for signs of redness or discharge and look for evidence of rubbing. In the older child, observe their ability to focus by asking them to follow a penlight as it is moved in specific directions. An infant will also fixate on and follow a penlight with their eyes. Evaluate pupillary response to light.

Assess the ears: Examine how the ears are positioned and aligned. Draw an imag nary line from the top of the pinna to the outside corners of the eye. Observe the child’s reactions during typical conversation to assess hearing. If a youngster speaks loudly, replies improperly, or is not audible, a hearing problem should be evaluated.

Assess the nose, mouth, and throat: Draw an imaginary line down the middle of the face to check for symmetry, then inspect behind the nostrils for any deformity, discharge, or bleeding. To examine the mouth and throat in the older child, the examiner should instruct them to hold their mouth as wide as possible and move their tongue to either side. In an infant or toddler, the examiner should use a wooden tongue blade and penlight to check the oral cavity and throat. Inspect the oral cavity for color and moisture and look for signs that might suggest an infection. Inspect the teeth for abnormalities, including the number and state of the child’s teeth. Any scents that could aid in determining the source of the patient’s ailment. On the breath of a child with diabetic ketoacidosis, for example, the pleasant or fruity odor of acetone may be noticed. An odor of bitter almonds may be detected in a child with cyanide oisoning [3].

Thorax and Lungs

Chest circumference is an important anthropometric parameter in monitoring child growth.

How to perform chest circumference: Using the nipple line as a guide, wrap the tape around the chest and note the measurement. With respiration, examine the size, shape, and movement of the chest. Also look for any retractions in the chest.

Adolescents: Look for signs of breast development in school-age children or adoles- cents.

Assess respiratory characteristics: Keep an eye on the child’s breathing rate, rhythm, and depth. Note any abnormal respiratory sounds such as stertor or stridor.

How to perform breath sound assessment: The examiner should auscultate the lung fields to assesses airflow through the tracheobronchial tree and report abnormal breath sounds such as rales, rhonchi, or wheezing.

Heart: The mitral valve sound, also known as the point of greatest impulse, is best heard in some newborns and children near the fourth intercostal space on the left midclavicular line.

Evaluating heart rate and rhythm. The examiner can evaluate the child’s heart rate by counting the beats for one full minute and pay attention to the heartbeat rhythm.

Assessment for cardiac abnormalities. Abnormal heart murmurs might indicate a congenital heart disease or other abnormality that warrants clinical investigation.

Evaluating cardiac function. To determine how well the heart functions, the examiner should examine the pulses in different parts of the body.

Abdomen: Slight abdominal protrusion is common in newborns and children.

Assess bowel sounds. The examiner should auscultate all nine regions of the abdomen with a warmed stethoscope while the child is quiet to assess bowel sounds.

Inspect the abdomen for distention, bruising, use of abdominal muscles during breathing, scars, feeding tubes, and stomas or pouches.

Gently palpate each abdominal quadrant for tenderness, guarding, rigidity, and masses. If the child complains of pain in a specific abdominal area, palpate that area last. Observe the child as you palpate.

Auscultate the presence or absence of bowel sounds in all quadrants. Gently palpate each ab- dominal quadrant for tenderness, guarding, rigidity, and masses. If the child complains of pain in a specific abdominal area, palpate that area last. Observe the child as you palpate.

Genital organ and rectum

Ethical standards should be followed when performing an examination of the genital organ and rectum in children. In the older child, the examiner should clearly explain the procedure before conducting the examination.

Inspection of the genital organand rectum: The examiner should inspect the genital organ and rectum while wearing gloves. Check the genital organ and perineal region for any lesions, irritation, or discharge.

Assess the testes: Testicular descent occurs at various stages throughout childhood. If a testis cannot be palpated, the examiner must initiate an evaluation for nonpalpable testis.

Back and limbs

The back and limbs should be examined for abnormalities.

Assess the back: The examiner should look for symmetry in the shoulder height and scap- ulae. Changes in proper alignment and other structural abnormalities should also be checked on the spine. The spine of a baby is C-shaped and flexible. As neonates develop motor abilities, secondary curvature in the cervical and lumbar spine form. The spine develops further as the youngster grows. The examiner should examine the back for pain, rashes, changes in skin color, swelling, and open wounds. Auscultate the posterior chest for normal and common abnormal breath sounds. In patients with suspected spine injury, make sure the head, neck and back are aligned during the examination.

Gait and posture analysis: Watch the child as they walk and check for any issues with their posture. Assess motor function in an upper extremity in an alert patient by instructing the child to “Squeeze my fingers in your hand.” To assess motor function in a lower extremity, instruct the child to “Push down on my fingers with your toes.”

Assess the extremities: Check for symmetry and any skin changes in the upper and lower limbs. During a physical examination, the child’s motions can be used to examine foot and an- kle alignment, muscle strength, and range of motion. Check.

Neurological assessment

• A pediatric neurological amination is the most challenging part of the physical examination.

• Assess the child’s responsiveness to stimuli using the AVPU mnemonic: Alert, Response to

• Voice, Response to Painful stimuli, and Unresponsive.

• Examine the child for signs of lethargy or irritability.

• Posture assessment: Full-term infants tend to keep their keep their fists clenched, upper limbs adducted and flexed at the elbows, and lower limbs abducted and flexed at the knees.

• Tone assessment: This can be done by examining the infant’s posture and activity while they are unattended, as well as handling the youngster. Pick up the baby and listen to their tone. Place the infant in the supine position, then gradually move them to a sitting posture while keeping an eye out for signs of head lag.

• Assess pupil reaction to light.

Diagnostic Test and Lab Results

The diagnostic tests performed are often limited to pulse oximetry, capnography, and point-of-care serum glucose levels. Additional tests and procedures are performed to reach a diagnosis or determine the extent of the patient’s injuries (Table 3).

| Test | Abnormal Result | Importance | Interventions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arterial blood gas | Low arterial oxygen and pH abnormalities | Indicates adequate ventilation | Manage ventilation by increasing and decreasing the rate |

| Oxygen saturation | Venous oxygen saturation outside the 70-75% reference range | Indicates adequate venous oxygen saturation | Improve oxygenation and ventilation |

| Arterial lactate concentration | High lactate levels | A high lactate concentration is a sign of illness A decrease in lactate levels is suggestive of treatment efficacy | See Shock Sequence |

| Arterial and central venous pressur monitoring | High or low pressure | May indicate adequate or inadequate fluid resuscitation | See Shock Sequence |

| Chest radiography | Lung conditions and complications related to these conditions | Detection of respiratory problems Verification of endotracheal tube position | See Respiratory Sequence |

| Electrocardiogram | Heart arrhythmias | Detection of heart disease | Depends on arrhythmia type |

| Peak expiratory flow rate | Low peak expiratory flow rate | If the test is properly conducted, the findings may indicate an underlying respiratory problem | See Respiratory Sequence |

| Echocardiogram | Valvular heart disease Congenital heart anomalies | Detection of cardiomyopathy and contractile dysfunction | Depends on the diagnosis |

Table 3: Examples of diagnostic tests that are used to assess problems with the cardiorespiratory system.

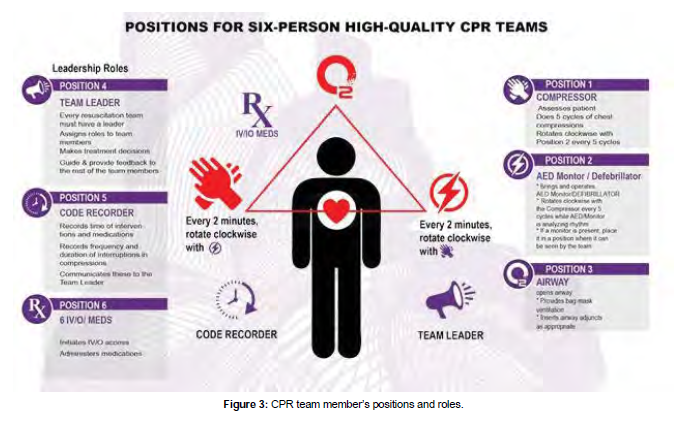

Teams and teamwork

Teamwork is important when providing patient care and is essential to patient safety. To be effective, team members must communicate, anticipate the needs of the team, coordinate their actions, and work coop- eratively. It is essential that all members of the team demonstrate respect for each other and communicate using a calm and confident tone [4 ,5 ].

Pediatric rapid response and resuscitation teams

Many hospitals have established strategies to improve patient outcomes by lowering the risk of cardiac arrest in unstable patients and lowering fatality rates when cardiopulmonary arrest occurs. These systems rely on fast response and resuscitation teams, which are made up of highly trained and skilled personnel. To achieve the best potential outcomes for each patient, healthcare providers on rapid response and re- suscitation teams must collaborate in a coordinated effort. A group of people with clearly defined tasks and duties working toward a common objective is referred to as a team.

The fast response team’s mission is to intervene promptly and efficiently to address the warning symptoms of impending cardiac arrest in order to avoid the arrest [6].

The resuscitation team’s purpose is to give pediatric advanced life support care to a youngster in respiratory or cardiac arrest as rapidly as possible. Patients in respiratory distress or shock in children may decompensate quickly, leading to respiratory and cardiac collapse. Highly trained teams are currently in place in critical care settings such as the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) or the emergency department (ED), and pediatric advanced life support treatment will be deployed soon. Patients outside of these situ- ations, owever, are also at danger of respiratory or cardiac arrest. As a result, all healthcare workers should be taught to spot early indicators of clinical deterioration in patients and to know how to swiftly launch an emergency response.

In most hospitals, the Rapid Response Team (RRT) is separate from the resuscitation team. In some facilities, RRT members may initiate resuscitation before the code team arrives if RRT members have received training in pediatric advanced life support.

Skills and best practices

Every team leader and member must demonstrate crucial abilities such as communication, critical think- ing, and problem solving in order to obtain the greatest potential results. Implementing effective and efficient teamwork, as well as demonstrating these vital core abilities, enables the team to respond quickly and effectively, improving patient outcomes.

Communication

When caring for a kid who is experiencing signs and symptoms of shock or a pediatric respiratory or cardi- ac emergency, communication is crucial. You must communicate with your colleagues, as well as the pa- tient and his or her family. Nonverbal messages given through body language, such as gestures and facial expressions, are also included in communication.

There are four important components to communication

Message: The content of the communication must be expressed clearly so that everyone involved un- derstands exactly what the message is.

Receiver: The person for whom the message is intended.

Feedback: The receiver’s confirmation that the message has been received and understood; an essential element of closed-loop communication.

Communicating with the Team

Clear and effective communication among team members is the foundation of effective teamwork. A se- lected team leader oversees the actions of the other team members when a team is working to provide care [7,8].

Effective communication

1. Be audible.

2. Clear messages

3. “Close the loop”

When receiving information

By repeating the task back to the sender, you can indicate that you received the message and that you understand it. Recognize the task’s beginning and completion. Avoid speaking over others and talk clearly in a calm tone of voice.

Healthcare Team and Family Communication

Communicate with family after the death of a patient

Despite the fact that quick reaction teams have become more common in pediatrics, there is no convinc- ing evidence that they boost survival rates. As a healthcare practitioner, you would be required to inform a patient’s family of their death. Even for healthcare professionals, dealing with death is challenging. In this situation:

1. Deliver the news in a straightforward manner and include information about upcoming activ- ities. Allow time for the family to process the facts. Allow time for the family to grieve; inquire whether they want you to contact or have you call anyone, such as other family members. Wait and respond to any inquiries the family might have.

Critical thinking

Critical thinking is the process of identifying the link between information and actions by thinking clearly and reasonably. When you utilize critical thinking, you are continually discovering new facts and situations, logically responding to the knowledge to determine your best next actions, and anticipating how those actions will affect the patient. In healthcare, critical thinking is an important skill, especially in pediatric advanced life support circumstances (Table 4).

| Disorder | Upper airway obstruction | Lower airway obstruction | Lung tissue disease | Central respiratory disorders |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Signs and Symptoms | Tachypnea | Tachypnea | Tachypnea | Variable |

| Stridor (typically inspiratory) | Barking cough Hoarseness Wheezing (typically expiratory) Prolonged expiratory phase | Grunting Crackles Decreased breath sounds | Normal | |

| Decreased airway movement | Decreased airway movement | Decreased airway movement | Variable | |

| Tachycardia (early); bradycardia (late) | ||||

| Pallor, cool skin (early); cyanosis (late) | ||||

| Anxiety, agitation (early); lethargy, unresponsiveness (late) | ||||

| Signs and Symptoms of Respiratory Distress and Respiratory Failure | ||||

| Respiratory Distress | Respiratory Failure |

|---|---|

| Airway open and maintainable | Airway not maintainable |

| Tachypnea | Bradypnea to apnea |

| Work of breathing (nasal flaring/retractions) | Increased effort progresses to decreased effort and then to apnea |

| Good air movement | Poor to absent air movement |

| Tachycardia | Bradycardia |

| Pallor | Cyanosis |

| Anxiety, agitation | Lethargy to unresponsiveness |

Table 4: Recognizing Respiratory Emergencies Flowchart.

The following refers to when you use critical thinking:

1. Make a quick assessment and decide on a line of action. Based on the patient’s health, work promptly to fill responsibility gaps in the team. Reassess the situation and adjust patient care as needed.

Problem solving

Problem solving is the capacity to use readily available resources to solve problems that are difficult or complex. Several reasons, such as a shortage of resources, might cause pandemonium during an emergency.

A device like an automated external defibrillator (AED) could not be easily available, or it might have a low battery. A parent may feel dissatisfied with the situation and try to interfere with care. Utilize any available resources, such as equipment, other team members, or other healthcare facility personnel.

Practicing and debriefing

Effective high-performance teams maintain their skills and expertise by practicing together on a regular basis. In addition, following each resuscitation incident, effective high-performance teams hold debriefing sessions. The goal of the debriefing session is to examine the decisions made and actions taken more

closely in order to discover chances for improvement at the system, team, and individual levels.

Roles and responsibilites

Every team member must be efficient in performing their roles as part of the resuscitation team, members

should bear in mind that it is imperative for them to adhere by the following standards:

1. They should understand their role.

2. Knowing their limitation.

Team leader

The main roles of a team leader are: assigning team member’s roles and responsibilities, making a decision regarding patient health, ensuring that his team members perform their duties as expected and correctingteam member’s actions if needed based on his / her proficiency in knowledge, skills, and leadership capabilities (Figure 3).

Team members

They are competent and knowledgeable in their roles.

Six-person high-performing resuscitation team

1. Team leader

2. Compressor

3. Airway manager

4. AED/defibrillator/CPR coach

5. I.V/I.O provider 6 -time recorder

Learning objectives

Readers should be able to:

• Define the terms respiratory distress, respiratory failure, and respiratory arrest.

• Describe how to deal with respiratory distress, respiratory failure, and respiratory arrest in an emergency.

• Explain the pathogenesis, symptoms, and emergency care for croup, foreign body aspiration, and anaphylactic patients.

• Go through the pathophysiology, signs and symptoms, and emergency management for asthma and bronchiolitis patients.

• Explain the etiology, pathophysiology, sign and symptom patterns, and emergency management for patients with lung tissue disease and central respiratory illnesses.

• Respiratory emergencies continue to be a leading source of morbidity and mortality in children around the world. The patient’s outcome could be greatly improved by prevention, early detection, and proper rapid care of various respiratory disorders.

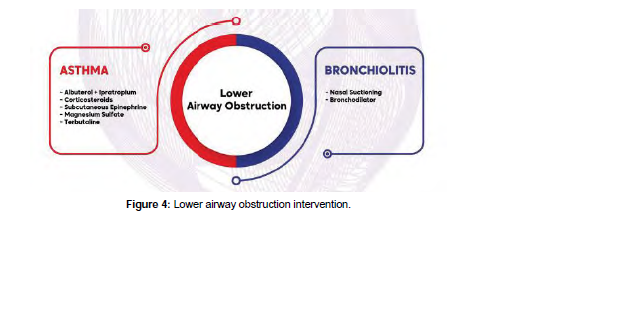

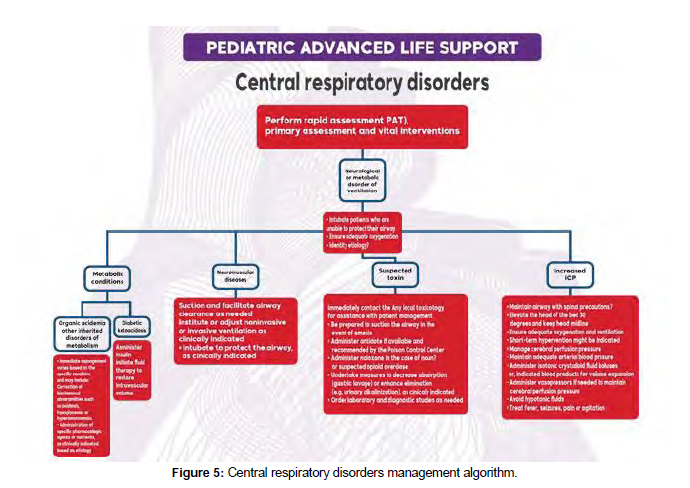

Though some specific disease processes may require special intervention, still, the main management guidelines for respiratory pathologies could be categorized into upper airway pathology, lower airway disease, lung pathology, or disordered control of breathing (Figure 4). While some patients may have a com- bination of two or more of such pathologies, still, these categories could help early recognition and fast intervention pathways for the treating team.

Definition of respiratory distress and respiratory failure

Respiratory distress is defined as a clinical state characterized by an increased respiratory rate (tachypnea) and respiratory efforts (increased work of breathing). Respiratory distress manifests as altered breathing pat- tern (tachypnea, slow respiratory rate, or weak respirations), forceful breathing efforts, obstructed breaths, or chest retractions.

In this pathophysiological state, the child attempts to maintain adequate oxygenation and gas exchange despite a respiratory pathology. However, if the child gets fatigued or the respiratory function deteriorates further and adequate gas exchange cannot be maintained, the child progresses to respiratory failure, which is defined as a paO2 50 mmHg (inadequate ventilation).

Upper airway disorders

Pathophysiology: Understanding the distinctions between adult and pediatric upper airway anatomy is critical for under- standing pathophysiology. In comparison to adults, children have larger heads and occiputs, resulting in hyperflexion of the airway when lying flat and supine. They also have a larger tongue and smaller jaw.

The pediatric larynx is funnel-shaped, the cricoid is C4 at birth, descending to C6 at age ten, and pediatric supraglottic cartilages are softer and more distensible than adult supraglottic cartilages, leading to dy- namic collapse at times. From birth to the first several months of life, babies are forced to breathe via their noses.

Children consume more oxygen at rest than adults in terms of lower airway physiology, as their resting metabolic demand is 2 to 3 times that of an adult. They also have a decreased functional residual capacity, which means hypoxemia and hypercarbia occur quicker during apnea.

Poseuille’s Law states that even a tiny reduction in the diameter of a child’s airway can be fatal. Edema, ste- nosis, a foreign body, or even mucous can cause this. Alveoli are mature in babies from 36 weeks onwards, but they continue to develop with septation and microvascular maturation from birth until roughly 8 years old. As a result, the surface area for gas exchange is less in pediatric patients [9].

Symptoms and signs

Upper airway blockage in children is a rather common cause of respiratory discomfort and failure. The nasal cavity, pharynx, and larynx are all parts of the upper airway. Infection (such as croup), airway edema (anaphylaxis), and foreign body airway obstruction are the three most common causes of upper airway blockage.

Other factors can also have an impact on upper airway patency. These could be caused by structural factors such as enlarged tonsils or adenoids, or by impaired upper airway control caused by a reduced level of consciousness.

A change in the sound of the child’s voice or cry, a barking cough, hoarseness of voice, or stridor are some key signs that will help you discover upper airway obstruction, along with other indicators of respiratory distress.

Upper airway obstruction symptoms are normally more visible during inspiration, as opposed to lower air- way obstruction symptoms, which are usually more noticeable during expiration. Marked chest retractions, significantly reduced or missing breath sounds, declining respiratory effort, weariness, and head-bobbing with each breath are all dangerous indicators of impending upper airway obstruction.

Diagnostics tests and procedures

Tests to confirm the etiology of upper airway pathology in children are usually postponed until the child’s airway patency is secured, to prevent any further airway compromise with agitation during blood sampling or other diagnostic procedures.

After the patient’s airway is stabilized, investigations may include general workups, such as CBC and renal profile, or more specific tests, such as respiratory viral screening with immune fluorescence or PCR testing for specific viral etiologies (Influenza, Parainfluenza, and respiratory syncytial virus). Radiological imaging could show the extent of upper airway compromise, but the risk: benefit ratio must be considered.

before sending the patient to the radiology department, especially since the initial management depends more on the clinical picture. If a foreign body is a potential cause for the upper airway compromise, early involvement with airway experts is warranted, in case surgical airway is needed while arranging for con- firmatory radiological imaging or endoscopy (usually rigid bronchoscopy could be both diagnostic and therapeutic in some of these children.

Emergency care of upper airway obstruction

Management of croup: Croup is a common viral respiratory illness affecting 3% of children six months to three years of age. It is managed based on its severity level, though a scoring system is not necessary, the most widely studied and commonly used is the Westley Croup Score.

In mild croup, usual symptoms are a hoarse, bark-like, brassy cough, without stridor at rest, and mild re- tractions. Intervention for mild crop consist of oral steroid (dexamethasone) and observation

The symptoms of moderate croup include inspiratory stridor and retractions at rest. The patient is usually calm but may have frequent barking or hoarse cough. Interventions for moderate croup include racemic epinephrine nebulizer and oral dexamethasone, with reassessment. Oxygen should be administered to children with hypoxemia.

In severe croup, the kid will have significant agitation or lethargy as the hypoxia worsens. Interventions are identical to those used for moderate croup, and the kid should not eat or drink anything.

Also, consider using heliox, which is a helium-oxygen mixture that helps to lower air flow resistance and so reduces the child’s work of breathing. Because of the child’s growing hypoxemia and hypercarbia, many of the early symptoms may not be as noticeable if the youngster is on the verge of respiratory failure.

The barking cough may sound weaker, the stridor may become less apparent, and retractions may become less obvious as lethargy worsens. The loss of awareness should inform the treating team that approaching respiratory failure needs to be addressed immediately.

Another red flag is a drop in oxygen saturation of fewer than 94 % despite the use of supplemental oxygen. High concentration oxygen (high FiO2) using a non-rebreathing mask or, if insufficient, assisted ventila- tion with BMV or non-invasive ventilation (NIV), if needed, for oxygen saturation of 94% is used to treat approaching respiratory failure. Airway experts for potentially difficult endotracheal intubation should be consulted ahead of time, and a surgical airway (tracheostomy) should be considered if necessary. It’s also a good idea to start with IV or IM dexamethasone and nebulized racemic epinephrine.

Management of anaphylaxis with airway edema

Following the initial basic therapies for respiratory distress and failure, the following particular interven- tions for anaphylactic management are used. Consider IM epinephrine, IV antihistamine (such diphenhy- dramine), and IV corticosteroid therapy.

As needed, administer albuterol nebulization to individuals with bronchospasm. Airway experts should be consulted early, as with any upper airway impairment, to prepare for the likelihood of endotracheal intubation if respiratory failure occurs. For patients with anaphylaxis and hypotensive shock, give fluid IV bolus with normal saline 20 mL/ kg. If hypotension persists despite the IM epinephrine and fluid bolus, consider IV epinephrine with age-appropriate dosing as a continuous infusion. Continue to utilize the Evaluate-Identify-Intervene sequence until the patient is stabilized.

Management of foreign-body airway obstruction

Following the general guidelines for the infant or child who is choking, the following interventions are employed for the management of Foreign-Body Airway Obstruction after the initial general interventions for respiratory distress and failure, as described above.

If the infant or toddler is choking but can cough and make sounds, the airway obstruction is partial, and the child should be closely monitored and given time to cough the obstruction away. Until the Foreign-Body is removed from the airway, careful surveillance is required. These interventions must be used if the infant is cognizant and has a total obstruction, as shown by the inability to cough, cry, or make noise:

1. Infants under one year: Make five back slaps and five chest thrusts.

2. Give abdominal thrusts to children under the age of one.

3. Start CPR with chest compressions if the infant or youngster becomes unresponsive.

Note that in this setting, you must provide chest compressions even if the unresponsive child has a pulse. The aim of these chest compressions is to provide positive intrathoracic pressure that can expel the For- eign-Body Airway Obstruction. After the chest compressions cycle, the mouth should be checked for the foreign body. If the foreign body is seen, remove it under direct vision, but do not make a blind finger sweep.

Lower airway disease

Lower airway obstruction may occur at the levels of the trachea, bronchi or bronchioles. Conditions of pediatric lower airway include bronchiolitis and asthma. It is characterized by wheezing and hyperinflated lungs, together with other signs of respiratory distress. Common causes in infants and children include bronchiolitis, asthma, and foreign body inhalation.

Pathophysiology

Bronchiolitis is most common in babies and toddlers (2 months to 2 years of age ). Infection with the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is the most common cause. The diagnosis is mostly clinical, with investi- gations playing a minor role. In asthma, interactions between environmental triggers and genetic factors result in airway inflammation, narrowing and excessive mucus production, which limits airflow and leads to functional and structural changes in the airways in the form of bronchospasm, mucosal edema, and mucus plugs.

Signs and symptoms

Bronchiolitis in infants present with a low-grade fever, a dry and persistent cough, difficulty feeding, and rapid or noisy breathing (wheezing).

In an acute asthma episode, symptoms vary in severity. Infants and young children suffering a severe ep- isode may display the following: breathless during rest, feeding refusal, sitting upright or tripod position, talk in words (not sentences), and maybe agitated. With impending respiratory arrest, the patient becomes confused and drowsy. However, adolescents may not exhibit these symptoms until they are in complete respiratory failure.

During a severe asthma attack, the following findings are common: respiratory rate is often greater than 30.

breaths per minute, accessory respiratory muscles are usually used, chest retractions, heart rate is greater than 120 beats per minute, loud biphasic (both expiratory and inspiratory) wheezing can be heard, pulsus paradoxus is common (20-40 mm Hg), oxygen saturation on room air is less than 91 %. In status asthmat- ics with impending respiratory arrest, findings include paradoxical thoracoabdominal movement occurs, absent wheezing (i.e., silent chest by auscultation), with severe hypoxemia leading to bradycardia.

Diagnostic test and procedures: Diagnosis is usually made on clinical basis. A chest X-ray reveals hyper inflated lungs and prominent bronchial markings; radiography may also reveal parenchymal lung disease, pneumonia, atelectasis, congenital anomaly, or a foreign body.

Screening for viral triggers for the asthma attack or bronchiolitis could help establish the pathogen, such as immunofluorescence for RSV in nasopharyngeal aspirates.

Specific emergency management: Bronchiolitis treatment with nasal suctioning, humidified oxygen and other supportive measures are the mainstays of management. A trial of inhaled racemic epinephrine or systemic steroids may be considered for non-responders. Asthma is managed with albuterol/salbutamol and ipratropium nebulization, oral corticosteroids or IV depending on the severity, and magnesium sulfate IV. In severe cases, salbutamol IV could be used in the acute care areas (ER or PICU). Noninvasive Ventilation (CPAP or NIV with bi-level settings) could help patients with severe lower airway disease, till other modalities of treatment reverse the small airway disease pathology. Early consultation and administration of CPAP / NIV with a CPAP / NIV professional is recommended, since this may prevent the need for endotracheal intubation in these patients.

Lung tissue disease

Lung tissue disease refers to conditions that affect the alveoli and interstitium of the lungs, influencing gas exchange via the alveolarpulmonary capillary interface. They also have a negative impact on lung compli- ance. Infectious and aspiration pneumonia are two common diseases in children and newborns.

Pathophysiology

Pneumonia is an infection, aspiration, or toxic agent-induced inflammation of the lung parenchyma. Bacte- ria, viruses, mycoplasma, and fungi can all cause infectious pneumonia. Pneumonia can affect one or more lobes of the lungs (lobar pneumonia) or the alveolar walls (alveolar pneumonia) (interstitial pneumonia ).

Aspiration pneumonia is caused by foreign, nongaseous material contaminating the lower respiratory tract, such as saliva, gastric contents, aspirated food, or chemicals (e.g. hydrocarbons). Bleeding, necrosis, surfactant impairment, and pulmonary edema result from the injury to the lung tissue, all of which might compromise lung compliance or create ventilation problems.

Pulmonary edema can be either noncardiogenic or cardiogenic in nature (i.e. arising from heart disease or dysfunction).

Excessive blood flow to the lungs or increased pressure in the pulmonary veins causes fluid transudate and alveolar edema in cardiogenic edema, which can compromise lung compliance or create breathing problems.

Noncardiogenic edema is a side effect of a variety of lung disorders, such as aspiration pneumonia. Exu- date of fluid into the alveoli and interstitial spaces comes from diffuse injury to lung capillaries and alveoli. Whatever the source, pulmonary edema reduces lung compliance and can induce obstruction of the lungs’ smaller airways.

Signs and symptoms

Pneumonia may present with fever, cough, decreased breath sounds, hypoxia, malaise, nasal flaring, chest pain, retractions, shortness of breath, and tachypnea.

For pulmonary edema, signs and symptoms include crackles, a moist cough, tachypnea, labored breath- ing, tachycardia, and anxiety or confusion that is associated with poor oxygenation. The sputum is may be frothy white or blood-tinged.

Diagnostic test and procedures

CXR…this test can give pictures of the structures inside your child’s chest, such as the heart, lungs, and blood vessels and can help rule out other lung diseases cause the child’s symptoms.

A high-resolution CT scan (HRCT). An HRCT scan uses X-rays to create detailed pictures of the child’s lungs and can show the location, extent, and severity of lung disease.

Lung function tests: These tests measure how much air child can breathe in and out, how fast he or she can breathe air out, and how well child’s lungs deliver oxygen to the blood. Lung function tests can assess the severity of lung disease. Infants and young children may need to have these tests at a center that has special equipment for children.

Specific emergency management

1. Perform child’s initial assessment and take focused history.

2. Put the child in a comfortable position, usually sitting up.

3. Connect ECG monitor, pulse oximeter and provide supplemental oxygen, as needed Make a first examination and get a detailed history.

4. For pneumonia patients if complaining from wheezes, we can give inhaled albuterol and clear secretions if present. Blood culture is done and antibiotics are given in case of suspected bac- terial pneumonia. Antipyretics are given for fever.

5. For patients with pulmonary edema, the management depends on source of the problem. For cardiogenic pulmonary edema, a diuretic helps with fluid removal, Giving vasopressor is important to improve BP If the patient’s condition worsens to respiratory distress or failure, we need to consider assisted ventilation (invasive or noninvasive).

General airway management

Management of respiratory emergencies may require procedures like opening the airways, airway suc- tioning, using an airway adjunct, giving supplemental oxygen or performing BMV (please confirm) (Figure 5).

General respiratory management interventions

Any pediatric respiratory illness should be treated with a variety of therapies aimed at stabilizing the pa- tient’s state. Other specialized therapies are employed to reverse and treat the underlying pathology when oxygenation and ventilation are stabilized, as will be addressed further. These general interventions are carried out as part of the “Evaluate, Identify, and Intervene” process for managing the airway, breathing, and circulation, as detailed below.

' Opening the airway

In an unresponsive youngster, the tongue might restrict the airway. The decrease of muscular tone in the neck and base of the tongue might also restrict the airway if the unconscious patient is supine. Snoring respirations are a symptom of airway blockage caused by tongue and soft tissue displacement if the child is breathing normally.

The upper airway blockage caused by the tongue in an apneic kid may go undiagnosed until ventilation is attempted. Because the tongue is linked to the mandible, the head tilt–chin lift or jaw-thrust moves the patient’s jaw forward, lifting the tongue away from the posterior pharynx.

Head tilt–chin lifts

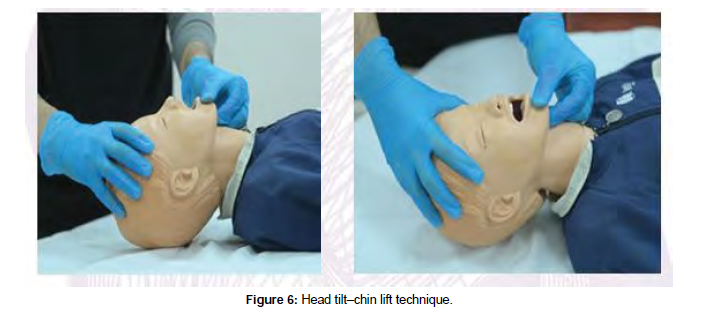

The preferred procedure for opening the airway of an unconscious child without a suspected cervical spine injury is the head tilt–chin lift. Place the youngster in a supine posture to perform the head tilt–chin lift procedure.

Apply firm backward pressure with the palm of your hand on the patient’s forehead to gently tilt the child’s head back into the neutral or slightly extended head position. Place the fingertips of your other hand be- neath the bony section of the child’s chin and gently raise the chin forward to open the airway (Figure 6).

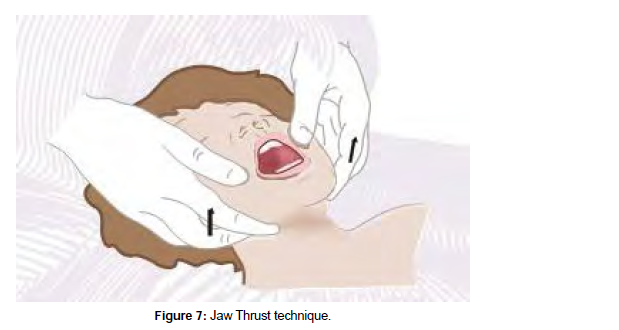

Jaw thrust

The jaw push is a manual maneuver used to access the airway of a patient who has a suspected cervical spine injury and is unable to extend his or her neck. Place the youngster in the supine posture to begin this procedure.

Grab the angles of the victim’s lower jaw with the tips of both hands’ index or middle fingers, one on each side of the child’s head, and lift, moving the mandible outward and upward, while keeping the child’s head in the neutral position (Figure 7).

Suctioning

Suctioning is the medical procedure used to remove secretions from the child’s nose (nasopharynx), mouth (oropharynx), or trachea. Indications for suctioning are signs of secretions in the airway, such as a wet cough, bubbling of mucus or mouth drooling.

Soft suction catheter: A flexible, long, narrow piece of plastic called a soft suction catheter is used to suck thin secretions. The catheter can be introduced by an oral or nasal airway, an endotracheal tube (ETT), or a tracheostomy tube. Before using the soft suction catheter, power on the suction device and ensure that suitable mechanical suction is present.

When preparing to suction through an ETT or tracheostomy tube, select a suction catheter with a diameter that is about one-half that of the tube. This will help to ensure that the ETT is not blocked or dislodged during the suctioning procedure. Measure from the tip of the nose or corner of the mouth to the bottom of the earlobe or angle of the mandible to determine the optimum catheter insertion depth for nasopharyn- geal suctioning. In infants and early children, this measurement is usually 4 to 8 cm. In older youngsters, it is 8 to 12 cm. A side opening is located at the proximal end of most suction catheters that would be cov- ered with the thumb to produce the suction effect.

Initially, gently insert the suction catheter without applying suction. Then to apply suction, cover the port on the catheter hub with your non-dominant thumb while gently withdrawing the catheter. Rotate the catheter between your other dominant thumb and forefinger as you withdraw the catheter (Table 5).

| Head Tilt-Chin Lift | Jaw Thrust without Neck Extension | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Indications | 1. Unresponsive pa tient who does not have 2. Unresponsive patient who is unable to protect his or her own airway |

1. 2. | Unresponsive patient with possible cervical spine in a mechanism for cervical spine injury Unresponsive patient who is unable to protect his or protect his or her own airway her own airway |

| Advantages | 1. Simple procedure 2. Noninvasive 3. Requires no special equipment |

1. 2. 3. |

Noninvasive Requires no special equipment May be used with cervical collar in place |

| Disadvantages | 1. Head tilt hazardous to patients with cervical spine injury 2. Neck hyperextension can cause an airway obstruction 3. Does not protect the lower air- way from aspiration |

1. 2. 3. |

Difficult to maintain Requires second rescuer for bag-mask ventilation Does not protect the lower airway against |

Table 5: Opening airway techniques.

Rigid suction catheter: The rigid suction catheters, also known as“tonsil tip” or Yanker suction catheters, are made of harder plastic and angled to aid in the removal of thick secretions and particulate materials from the oropharynx. A rigid suction

References

- Berg RA, Nadkarni VM, Clark AE (2016). Incidence and outcomes of cardiopulmonary resuscita- tion in PICUs. Crit Care Med 44:798-808.

- Brissaud O, Botte A, Cambonie G (2016). Experts’ recommendations for the management of car- diogenic shock in children. Ann Intensive Care 6:14.

- Fraser KN, Kou MM, Howell JM, Fullerton,KT, Sturek C (2014). Improper defibrillator pad usage by emergency medical care providers for children: an opportunity for reeducation. Am J Emerg Med 32: 953-957.

- Horeczko T, Enriquez B, McGrath NE, Gausche-Hill M, Lewis RJ (2013). The Pediatric Assessment Triangle: accuracy of its application by nurses in the triage of children. J Emerg Nurs 39:182.

- Marchese A, Langhan ML (2017). Management of airway obstruction and stridor in pediatric patients. Pediatr Emerg Med Pract 14:1-24.

- Mendelson J (2018). Emergency department management of pediatric shock. Emerg Med Clin North Am 36-427.

- Morgan C, Wheeler DS (2013). Obstructive shock. Open Pediatr Med Journal7:35- 37.

- Richards JB (2014). Wilcox SR. Diagnosis and management of shock in the emergency department. Emerg Med Pract 16:1-22.

- Shah S, Kaul A, Jadhav Y, Shiwarkar G (2020). Clinical outcome of severe sepsis and septic shock in critically ill children. Trop Doct. 50:186.

- Vereckei A (2014). Current algorithms for the diagnosis of wide QRS complex tachycardias. Curr Cardiol Rev. 10:262-276.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Citation: Alsohime F, Almazyad M, Shakour H, Temsah MH, Maghrabi K, et al.(2023) Paediatric Advance Life Support (PALS). Psych Clin Ther J 5: 209. DOI: 10.4172/tpctj.1000209

Copyright: © 2023 Alsohime F, et al. This is an open-access article distributedunder the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permitsunrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided theoriginal author and source are credited.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 4290

- [From(publication date): 0-2023 - Dec 08, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 3895

- PDF downloads: 395