Prostate Disorders and its Evaluation in Relation to Marital Status among Male of 40 Years and above Attending Tertiary Health Facilities Lokoja, Kogi State (2022)

Received: 10-Feb-2024 / Manuscript No. OMHA-24-127364 / Editor assigned: 13-Feb-2024 / PreQC No. OMHA-24-127364 (PQ) / Reviewed: 27-Feb-2024 / QC No. OMHA-24-127364 / Revised: 18-Apr-2025 / Manuscript No. OMHA-24-127364 (R) / Published Date: 26-Apr-2025

Abstract

Prostate cancer is a significant health concern, ranking as the most commonly diagnosed cancer in men aged 40 and above, with a mortality rate of 71 per 100,000. Early detection through Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) screening, though not entirely reliable, remains the most effective method for identifying prostate disorders. This study assessed the prevalence of prostate disorders and their association with marital status among men aged 40 and above. A total of 500 respondents (440 with prostate disorders and 60 as controls) were screened using venous blood PSA tests. Data on socio-demographics and potential risk factors were collected through face-to-face interviews using a structured questionnaire, followed by biopsy and Immuno Histo Chemical (IHC) analysis. Findings showed that among the 440 respondents, 284 were married, and 76 (26.8%) had prostate disorders. The distribution of prostate conditions included 36 cases (13.4%) of prostate cancer, 48 cases (17.9%) of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), 88 cases (32.8%) of prostatitis, while 99 (35.8%) were found normal. The highest prevalence of prostate cancer was observed in the 55–69 age group. Marital status significantly influenced prostate disorder risk, with single men having a higher odds ratio (5.8812) compared to married men (0.1700). This finding supports previous research indicating that marital status plays a crucial role in prostate cancer risk. Therefore, marriage and regular screening should be emphasized for men aged 40 and above.

Keywords: Prostate; Prevalence; Biopsy; Prostatitis; PSA

Keywords

Cancer; Metastasis; Cell proliferation; Somatic mutation; Genetic

Introduction

Cancer is a multifactorial disease influenced by a number of causes. The most feared non-communicable malignant disease affecting public health worldwide is polygenic complex genetic disease, which results from a succession of somatic mutations [1]. Malcolm and Albert, et al., have identified a class of disorders characterized by uncontrollably multiplying cells and ignoring the usual rules of cell division. Globacan states that multiple abnormal alterations in cell physiology, such as:

• Self-sufficiency in growth signal

• Insensitivity to growth inhibitory signals

• Evasion of programmed cell death

• Infinite proliferative potential

• Sustained angiogenesis

• Reprogramming of energy metabolism

• Evasion of immune destruction occurring annually and higher than 375304 (3.8%) death, are characteristics of malignancy

The countries in center and Eastern Europe have the lowest incidence rates, whereas other less developed regions have very high incident rates. Additionally, the majority of deaths among Asian communities occur in the black population. In 2012, the World Cancer Research Journal reported that there were 1.1 million cases worldwide and 307,000 deaths from cancer, accounting for 15% of all new cases in men. According to Dawam, et al., a prostate enlargement may be benign (non-cancerous) or malignant (cancerous). Benign prostatic hyperplasia or BPH for short, is an age related disorder that affects older men and is characterized by a simple expansion of the prostate gland. The most prevalent ailment that affects men is called Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH), which is present in 50% of men over 60 and has histological evidence in over 80% of men over 75. Conversely, malignant cancer is a class of disorders defined by the unchecked division and proliferation of aberrant cells. There could be fatalities if the spread is not stopped. Many cancers have known causes, including lifestyle factors like tobacco use and excess body weight, as well as non-modifiable factors like inherited genetic mutations, hormones and immune conditions. However, the exact cause of many cancers is still unknown, especially those that occur in childhood [2]. These risk factors may originate and/or encourage the progression of cancer concurrently or sequentially. Racism and ethnicity will undoubtedly be factors, since reports have indicated that black males in Africa are more likely to develop prostate cancer. Nonetheless, African-Americans of other racial groups had significantly greater incidence and death rates. According to reports, prostate cancer rates among males in the Caribbean are the highest globally. The fact that these African descendants have historically had a worse prognosis for their diseases and are more likely to present at a younger age with more advanced disease makes the situation even worse. This confirms autopsy reports that, when compared to age-adjusted cohorts of Caucasian men, African-American men aged 20 or older who passed away from other causes had a higher incidence and grade of intraepithelial prostate neoplasia. Furthermore, African-American patients have larger tumor volumes, according to multiple investigations into the pathologic features of prostate cancers. Early-stage prostate cancer often progresses undetected and shows no symptoms, so it may not even require treatment. However, nocturia, difficulty urinating, and increased frequency of urination are the most common complaints; these symptoms can also be brought on by prostatic hypertrophy. In more advanced stages of the disease, back pain and urine retention may appear because the axis skeleton is the most commonly affected site of bony metastatic disease [3].

PSA (Prostate-Specific Antigen)>4 ng/mL is a glycoprotein that is normally expressed by prostate tissue and elevated plasma levels of this protein are used to detect many prostate cancers. But since elevated PSA levels have also been reported in healthy men, a tissue biopsy is the practical gold standard for confirming prostate cancer. Not only are genes implicated in the inherited form of prostate cancer identified and detected, but studies also focus on mutations that occur in the acquired form of the disease. An extensive examination of the prostate cancer epidemiology and risk factors is required to fully understand the connection between genetic mutations and the role of the environment in causing these mutations and/or promoting tumor progression. It will be feasible to identify men who are at risk if the causes and risk factors for prostate cancer are better understood [4]. According to a 2014 IARC study, prostate cancer is becoming a more serious problem in Africa, where it was responsible for 28,006 deaths in 2010 and is expected to cause 57,048 deaths by 2030 if aggressive interventions are not put in place. Prostate cancer in men under 40 is not common. The prognosis of untreated or improperly managed cases is typically poor, particularly in developing nations and treatment modalities for prostate cancer are proving to be challenging. The high expense of the drugs and surgeries needed to treat patients who have a diagnosis may be the cause of this [5].

According to the World Health Organization, thirty percent of cancers are curable if discovered early, thirty percent can be treated with a prolonged survival if discovered early and thirty percent of cancer patients can receive palliative care and symptom management. Like many other health issues plaguing Nigeria's developing nations, early prostate cancer detection has proven difficult for a variety of reasons, the most fundamentally socioeconomic [6]. However, as of right now, there are no proven methods for preventing prostate cancer through lifestyle changes or preventive interventions. For this reason, knowing what factors influence PC uptake will be extremely helpful in preventing the disease from developing. Prostate cancer screening is not widely done in Nigeria, despite the fact that it is the most common cancer diagnosed in men and the primary intervention. Odunayo and Ogundele have shown this. Practically speaking, this means that most patients have advanced disease when they come to the hospital [7]. Men with advanced-stage tumors typically have no chance of recovery, though palliative care may be helpful. It would therefore be reasonable to assume that the morbidity and mortality associated with prostate cancer, including urinary obstruction and painful metastases, would be significantly reduced by a screening program that could accurately identify asymptomatic men with aggressive localized tumors [8]. PSA screening has made it possible to identify and treat the condition early in developed nations. However, a variety of sociocultural and political factors have kept routine screening low in developing nations, especially in Africa. These factors have resulted in lower detection rates, inadequate management and higher disease-related mortality. The work of Moses, et al., which unequivocally demonstrates the association between low education and prostatic diseases among Black Americans, further validated the study by Akwu, et al., on the low uptake of Prostate Serum Antigen (PSA) screening services among the Igala People of North Central Nigeria. However, a number of studies have established the inconsistent relationship between the risk of prostate cancer and Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs). Additionally, it is thought that abnormal prostrate growth may be encouraged by aging-related changes in the estrogen and testosterone ratio. A lower ejaculatory output in a male who is otherwise healthy is also linked to a higher risk of prostate cancer, particularly if the cancer develops in early adulthood [9]. The increased incidence of prostate cancer is again caused by longer life expectancies and modern lifestyles that delay sexual activity. This research project, however, aims to determine the prevalence of prostate cancer and the relationship between prostate disorder and marital status in Lokoja city [10].

Statement of the problem

Prostate cancer was identified as the most common cancer among men in Nigeria between 2009 and 2013, according to data collected over a three-year period by the Nigeria System of Cancer Registry (NSCR). According to studies conducted thus far, men in Nigeria are more likely than men in Western countries to develop prostate cancer, especially at ages 50 and above. Prostate cancer has emerged as a health issue and is the most common cancer diagnosed in Nigerian men, according to Ifere, et al., and WHO 2019 [11]. It is also highly associated with a mortality rate of 71/100,000. These culminate to the decision of taking drastic steps in checking the prevalence to ascertain the status of this disorder in Nigeria and Kogi state in particular using the major health facilities as tools to driven the research home.

Justification

The health effects of prostate disorders have become a scourge all over the world especially among the black men where the prevalence is said to be high. Although the causative agent of this disorder is unknown and the only way to curb out the effect is to employ a pointer diagnosis as PSA for early detection. This to some extent, helps to ameliorate the effect or total cure, hence metastasis leading to mortality rate is unraveled or prevented [12].

Aim and objectives

The overall aim of this study is to evaluate the association between prostatic tumor and marital status among males of age 40 and above attending government main health facilities within Lokoja metropolis.

Therefore, the objectives of this study are:

• To assess the prevalence of prostatic disorder among men based on age bracket in Lokoja metropolis.

• To determine the most probable age bracket affected with these medical disorders.

• To ascertain the relationship between prostate tumor and marital status.

• To investigate the prostatic tumor features by immunohistochemistry markers using Alpha-methylacetyl-coA racemase and myoepithelial (P63).

Null hypothesis

• There is no significant difference between age bracket and prostatic disorder.

• There is no significant difference between the probable age bracket and prostate disorder.

• There are no significant differences between prostatic tumor and marital status.

• There is no significant difference between the uses of immunohistochemistry markers on prostate tumor.

Scope of study

This study was limited to assess the prevalence of prostate disorder among men of age class of 40 and above [13].

To carry out a test of association between prostate cancer and marital status to see if there is any correlation between the two.

Significant of study

If an association between prostate cancer and marital status is established at the end of this study:

• Men with classes of polygamous, monogamous or without wife will be advised as the case may be.

• Male of class age 40 and above will be advised to go for regular checkup especially if their statutorily engaged.

• The use of sexual enhancer therapy or concoction should be discourage.

Literature Review

There is a significant difference in the prevalence of prostate cancer between black and white men worldwide, but there are no compelling explanations for this. This discrepancy might be explained by research looking at black men from various populations to determine whether there is a positive influence related to these men's racial backgrounds. Many black men who live outside of Africa have ancestral ties to Nigeria, so it is hoped that exploratory research projects coming out of the nation will help explain the discrepancy. According to Odedina, et al., the primary focus of this research ought to be on the genetic and environmental risk factors specific to this group. According to Ogunbiyi and associates of the Ibadan Cancer Registry, there was a noticeable increase in cap in Nigeria in 1999. It jumped up to the top spot in 1996, representing 11% of all cancer cases in males, from eighth place in 1969. Research from Maiduguri, Benin, Zaria and Kano revealed that the percentage of cancers with caps was 16.5%, 9.2%, 7.13% and 6.15%. Reports from every part of the nation highlight the pattern of late presentation among CaP patients in Nigeria. About two thirds of patients from both the South and the North presented with metastatic disease and 91% and 94.2% presented with complications. Osegbe found that mortality was generally high, with 64% of people dying within two years. Rare reports of orbital metastases from Ibadan have been made; these were usually to the spine, accompanied by paraplegia or paraparesis [14].

Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH), an enlargement of the prostate gland that is not malignant, is a condition that primarily affects older men according to their age. More than 80% of men over 80 who have histological evidence of the condition suffer from BPH, the most common condition affecting men. It affects 50% of men over 60. A portion of the BPH symptoms may be related to racial or ethnic disparities. Higher smooth muscle tone and resistance within the enlarged gland (the dynamic component) and direct Bladder Outlet Obstruction (BOO) from the enlarged tissue (the static component) have been related to overall Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (LUTS), according to Chan [15]. The term Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (LUTS) refers to a group of symptoms that can be both obstructive and irritating (e.g., straining to start urination, feeling as though the bladder is not completely empty), hesitation and weak and interrupted urine stream. Vaginal symptoms are a common side effect of prostate enlargement and they may lead to pathological alterations in the bladder. Long-lasting blockages have the potential to cause renal insufficiency, Acute Urinary Retention (AUR), bladder calculi, recurrent UTIs and hematuria. Age-related LUTS due to BPH increases in frequency. Forty percent of men experience moderate to severe symptoms between the ages of sixty and eighty and eighty percent do not. By the age of ninety-nine, nearly every man has microscopic BPH. According to studies of the US population, the moderate-to-severe LUTS increased to nearly 50% by the eighth decade of life. Men 70 years of age and older, according to Wei, et al., have moderate to severe Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (LUTS). With an overall population growth size of 34.7 divisions, AUR is emerging as a symptom of BPH progression, rising from a prevalence of 6.8 divisions per 1000 patients annually. According to a different study, 90% of men between the ages of 45 and 80 have LUTS of some kind. Androgens are crucial for the growth and development of the prostate as well as the entire male genital tract. They promote the differentiation and proliferation of the gland's stromal and epithelial compartments. Prostatic stromal and epithelial cells both express the Androgen Receptor (AR), which is activated by androgens. Since estrogen is a metabolite of testosterone as well, androgens may not be the only important hormone in BPH. Therefore, estrogens may also be responsible for the BPH induction that is ascribed to androgens.

Anatomy of the prostate gland

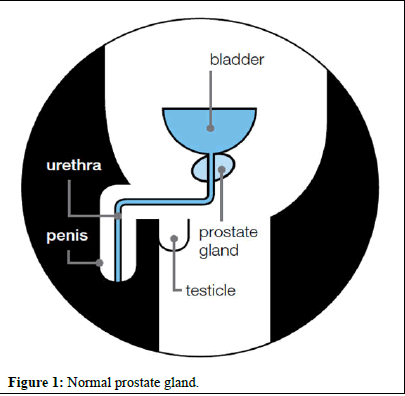

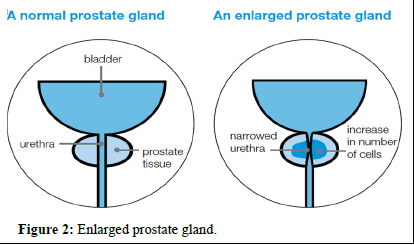

The largest accessory gland in the male reproductive system is the prostate gland. It secretes a seminal fluid, which is a thin, slightly alkaline fluid. It is made up of stromal and glandular components that are firmly fused together inside a false capsule. The prostate capsule's outer layer is covered by collagen and its inner layer is composed of smooth muscle, according to Lee et al. The prostate receives its vascular and nerve supply from the branches of the internal iliac artery and the prostatic plexus. The principal pathway for lymphatic drainage from the prostate gland is via the internal iliac nodes. Located in the subperitoneal space between the peritoneal cavity and the pelvic diaphragm, the prostate gland is situated posterior to the lower part of the symphysis pubis, anterior to the rectum and inferior to the bladder. The proximal urethra emerges from the bladder surrounded by the prostate gland, which is conical in shape and is commonly referred to as "walnut-shaped." An apex, a base, anterior, posterior and inferior-lateral surfaces comprise the prostate. The anterior fibro muscular stroma, Transition Zone (TZ), Peripheral Zone (PZ) and Central Zone (CZ) are its four zones or regions. At the end of the day, the prostate gland can be split into three sections: The base, situated directly beneath the bladder; the mid prostate, encompassing the verumontanum in the midprostatic urethra; and the apex, situated in the lower third of the gland. With its approximate 70% composition of glandular tissue, the peripheral zone is the largest of all the zones. It encircles the distal urethra and stretches along the posterior surface from the base to the apex. Compared to the other zones, the peripheral zone has a comparatively higher prevalence of post-inflammatory atrophy, carcinoma and chronic prostatitis. Because of the peripheral zone's many ductal and acinar elements and sparsely interwoven smooth muscle, T2-weighted MRI sequences frequently show a high signal intensity here. The transition and peripheral zones are positioned at the base of the prostate, with the central zone, which comprises approximately 25% of the glandular tissue. The structure that resembles a cone and narrows to an apex at the verumontanum surrounds the ejaculatory ducts. A longitudinal mucosal fold called the verumontanum, which forms an elliptical segment of the prostatic urethra, is where the ejaculatory ducts enter the urethra. Only two small lobules of glandular tissue, comprising only 5% of the glandular tissue, surround the proximal prostatic urethra, which is situated just superior to the verumontanum. Enlargement is caused by benign prostatic hyperplasia in this particular region of the glandular tissue. The peripheral zone remains unaffected when this hyperplasia occurs. An MRI's transition zone usually shows nodule areas with different intensities of signal, depending on the relative amount of glandular and stromal hyperplasia. Acinar and ductal elements as well as secretions are comparatively more abundant in glandular hyperplasia, which causes a higher sign intensity on T2-weighted MRI sequences. There are more muscular and fibrous components in stromal hyperplasia, which lowers signal intensity. According to Villiers, et al., hyperplasia of the periurethral glands may be referred to as "median lobe hyperplasia" depending on the origin of the hyperplasia. The transition zone, also known as the "surgical pseudo capsule," is then compressed to separate the transition gland from the peripheral zone. This compression can be subtle or noticeable as a faint, dark rim. The anterior fibro muscular stromal, which consists of smooth and fibrous muscular elements instead of glandular tissue, forms the convexity of the anterior external surface. The T2WI signal intensity in this region is consequently relatively low. The apical half of this region is densely packed with striated muscle, which blends into the gland and muscle of the pelvic diaphragm. As it spreads laterally and posteriorly, it thins to form the fibrous capsule that encloses the prostate gland. It typically shows up as a well-defined rim at the poster lateral aspects of the prostate on T2WI. Inside though the transition zone and the posterior zone of the prostate share similar embryologic origins, the transition zone accounts for only about 25% of cases of prostate cancer. This could be explained by the differences in the stromal component of these two zones. As fibro muscular stromal cells are more prevalent in the transition zone, it has been proposed that Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH), which predominantly affects them, is a disease of the fibro muscular stromal cells. The prostate gland is comprised of the anterior, posterior, inferior lateral surfaces, base, apex and rear. The urogenital diaphragm's superior surface is where the apex rests and makes contact with the levator ani muscle's medial surface. The prostate gland is composed of high T2 signal-intensity peripheral zone tissue that surrounds the distal prostatic urethra, according to Lepor, et al., to the bladder's neck. Digital palpation is an examination tool because the triangular, flat posterior surface of the rectum is supported by its anterior wall. A thin, film-like substance. The ratio of transition/central zone to peripheral zone tissue steadily decreases at the prostatic base, until almost all of the prostate gland is composed of mixed signal-intensity central/transition zone tissue. The prostate's base is connected to a layer of connective tissue known as Denonvillier's fascia, which divides the prostate and seminal vesicles posteriorly from the rectum. The prostatic urethra enters the prostate near its convex and narrow anterior surface. The anterior surface and inferior-lateral surface are connected above the urogenital diaphragm by the elevator fascia. Adipose and loose connective tissue surround the prostatic venous plexus, which is interspersed with lymphatics, arteries and nerves, at the poster lateral aspects of the prostate. These formations are known as neurovascular bundles because they include nerve fibers necessary for a healthy erection. Overall, the prostate is an extraordinarily well-innervated organ. The hypogastric and pelvic nerves, as well as the peripheral hypogastric ganglion, provide the prostate with both sympathetic and parasympathetic innervations. These nerves ultimately control the gland's physiology, morphology, growth, maturation, and regulation (Figures 1 and 2) [16].

Figure 1: Normal prostate gland.

Figure 2: Enlarged prostate gland.

Risk factors for prostate cancer

The following risk factors for incidence might differ from those for mortality (e.g., family history) and men with risk factors-especially those with a family history of prostate cancer-often experience elevated anxiety. If these men visit their primary care provider, it is imperative that they receive the best advice and support available to help them decide whether or not to get a PSA test. Prostate cancer does not have a known cause. A recent analysis of eighteen studies found no evidence that sex hormones influence prostate cancer risk.

Drinking and smoking: Research on nutrition and diet has found a direct link between alcohol consumption and smoking. Three meta-analyses revealed a strong association between heavy alcohol consumption and PCa incidence. According to the findings of a meta-analysis study on tobacco use, there has been a notable rise in PCa mortality and incidence as tobacco use has increased. Several studies have proposed various explanations for the relationship between smoking and tumor development and morbidity. For example, smoking has been associated with a higher risk of deaths from PCA related causes because it increases the metabolism of serum estrogens. Consequently, a more aggressive tumor phenotype is encouraged.

Lack of fresh fruit and vegetables: Several studies have shown that a diet containing certain vegetables (including tomatoes, cruciferous vegetables, soy beans and other legumes) or fruit juices (such as pomegranate) is associated with lower incidence of PCa. In this regard, results of a systematic study Jinyao 2013, showed that there is a significant association between receiving tomato-rich vegetables and tomato-rich products with reduced PCa incidence. Some case-control studies also indicated that the risk of PCa in people who take cruciferous is significantly lower than others.

Geography: Geographically, North America, Australia, New Zealand and Western and Northern Europe are the PCa-affected regions most frequently. Sub-tropical Africa, South America and the Caribbean are among the lowland middle-income regions estimated to have the highest PCa mortality rate.

Estrogens: Contrary to the early research on oestrogens, which was believed to be a protective factor against PCa and used as a treatment for advanced disease, evidence suggests that oestrogens may play a significant role in predisposing or even causing PCa. Human correlational data indicates that estrogens proliferate the prostate gland, which may play a role in the onset of cancer. Even though blood circulating estrogen levels may not correlate well with intraprostatic levels-especially in light of recent evidence regarding the intraprostatic oestrogen production-serum values offer an easily accessible surrogate marker to investigate associations between estrogens and PCa risk. Cussen, et al., found a relationship between polymorphisms in genes related to estrogen metabolism (CYP1B1 and CYP19) and PCa risk. Furthermore, an increasing amount of animal research indicates that estrogens may act as pro-carcinogens in the prostate. Studies conducted on a range of animal species suggest that estrogens through the stoma Estrogen Receptor (ER) α may contribute to the carcinogenesis and development of prostate cancer.

Race/ethnicity: The incidence of PCa was highest in African-American men from the Caribbean. Compared to white men, African-American men have a nearly twofold higher death rate from prostate cancer. Compared to non-Hispanic white men, men who identify as Asian-American or Hispanic/Latino had a lower incidence of PCa.

Occupation: Other studies' findings indicate that farmers who are exposed to diesel engine exhaust have a six-fold higher chance of PCA. According to a Taiwanese case-control study from 2016, hairdressers who used hair color were much more likely than other hairdressers to develop PCa. According to Doolan, et al., hair dye products contain about 5,000 chemicals that are mutagenic and carcinogenic.

Family history: PCa diagnosis in a family member is called family PCa. Family PCA is estimated to affect 20% of families. Genes, lifestyles and environmental factors that are similar are some of the factors that contribute to PCa in families. First-degree family members have a PCA risk that is 2.3 times higher than that of other relatives, per research by Ventimiglia, et al. Men over 75 with a family history of PCa had a 30% to 60% chance of getting a PCA, according to a nationwide study. Five percent of PCa cases are hereditary. Inherited PCa is caused by a gene mutation that is inherited and passed down from one generation to the next. Men are more likely to have inherited PCA if they possess one or more of the following characteristics: PCa affects at least three of a family's first-degree relatives, as well as two generations or more of close relatives (such as a father, brother, son, grandfather, uncle, niece and nephew).

Genetic changes: The quantity of data and documentation pertaining to the hereditary aspect of prostate cancer risk is increasing. Several genes and chromosomal regions have been linked to PCa through a variety of linkage analyses, case-control studies, Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS) and admixture mapping studies. Pathogenic variants in genes of high and moderate penetrance, such as HOXB13, BRCA1, BRCA2 and the mismatch repair genes, raise the lifetime risk of prostate cancer from modest to high. The prostate-specific TMPRSS2 gene is expressed by the prostatic epithelium of both benign and malignant prostate cancers. It has been shown that androgens induce TMPRSS2 expression in hormone-responsive PCa cell lines. Consequently, it is postulated that in PCa positive for TMPRSS2-ETS gene fusions, TMPRSS2 drives ETS gene overexpression.

Obesity: There is contradiction in the results regarding the risk of obesity. Despite having a lower incidence of low-risk diseases, obese men have been shown in numerous investigations to have an increased risk of prostate cancer (PCa) compared to non-obese men. Why this conclusion was drawn is unknown. Furthermore, compared to non-obese men, obese men had substantially greater mortality rates and PCa-related risk. However, this conclusion is not supported by any survey. Thus, additional research is needed.

Prostatitis: Certain studies have shown a strong correlation between prostatitis and PCa. However, some additional research refuted this conclusion. A 2010 cohort study conducted in California revealed that those who had prostatitis also had a higher risk of PCa (RR)=1.30; 95%, CI: 1.10-1.54). The long term effects of PCa and infectious microbes on asymptomatic inflammatory prostatitis have been shown in numerous studies. One of the bacteria connected to PCa and BPH is the E. coli infection. Furthermore, additional studies found a link between PCa, prostatitis and the protozoan infection caused by STIs, T. vaginalis. More research in this area is required as the link between prostatitis and PCa has not always been conclusively shown.

Sexual activity/sexually transmitted diseases: Numerous studies have found a strong relationship between the prevalence of STIs and PCa. People who engage in sexual activity may be more susceptible to PCa due to the infectious agents they come into contact with Huang, et al. A meta-analysis study's findings also showed a strong correlation between PCa and STI (odds ratio (OR)=1.48, 95% CI=1.26 to 1.73), human papillomavirus (OR=+1.39, 95% CI=1.12 to 2.06) and gonorrhea (OR=1.35, 95% CI=1.05 to 1.83). Leit, et al., assert that since there is a strong correlation between ejaculation frequency and PCa in other studies, there is a protective factor for ejaculation in the prevention of PCa. A lower risk of prostate cancer was also observed in men who ejaculated more than five times per week. Leitzmann, et al., found in a cohort study that ejaculating more than 21 times per week reduces the risk of developing PCa. Both the mechanism and the reasons for the protective effect of ejaculation are still unknown.

Vasectomy: Based on two sizable cohort studies, a correlation between vasectomy and PCa risk was first proposed in 1993 with an RR of 1.6. Men who had vasectomy procedures done when they were younger were at a lower risk because the risk rose with age. Numerous studies have found a strong relationship between the prevalence of STIs and PCa. People who engage in sexual activity may be more susceptible to PCa due to the infectious agents they come into contact with Huang et al. A meta-analysis study's findings also showed a strong correlation between PCa and STI (odds ratio (OR)=1.48, 95% CI=1.26 to 1.73), human papillomavirus (OR=+1.39, 95% CI=1.12 to 2.06) and gonorrhea (OR=1.35, 95% CI=1.05 to 1.83). Leit, et al., assert that since there is a strong correlation between ejaculation frequency and PCa in other studies, there is a protective factor for ejaculation in the prevention of PCa.A lower risk of prostate cancer was also observed in men who ejaculated more than five times per week. Leitzmann, et al., found in a cohort study that ejaculating more than 21 times per week reduces the risk of developing PCa.

A recent meta-analysis reported a pooled RR of 1.37, with a linear trend suggesting a 10% increase for each additional 10 years since vasectomy. On the other hand, a meta-analysis of cohort studies suggested that vasectomy was not associated with increased risk of PCa. Therefore, research on this possible association is still under way.

Symptoms of prostate diseases

An enlarged prostate is the most common cause of urinary symptoms in men as they get older. It can cause your urethra to narrow, causing symptoms such as:

• A weak urine flow

• Needing to urinate more often, especially at night

• A feeling that your bladder has not emptied properly

• Difficulty starting to urinate

• Dribbling urine

• Needing to rush to the toilet-you may occasionally leak urine before you get there • Blood in your urine

You may have only a few of these symptoms or you may not have any symptoms at all. Without treatment, some men find that the symptoms of an enlarged prostate slowly get worse. These symptoms can be caused by other medical problems, lifestyle factors or certain medicines. They may be nothing to do with the prostate. If you have any of the symptoms above, you should visit your GP to find out what is causing them.

Clinical presentation

Reports from all region of the country emphasize late presentation as the pattern in Nigeria PCa patients. From both South and North about two third of patients presented with metastatic disease and 94.2% and 91% presenting with complicating respectively. Mortality was generally high with 64% dead within 2years in a review by Osegbe.

Diagnosis

There is growing concern that medical students are not growing enough skill in DRE, such that clinical diagnosis of cap may become a dilemma for the younger generation of doctors.

Histopathology: Research from every part of the nation revealed, in line with findings across the globe, that the most common histopathology type is adenocarcinoma. A moderate percentage of prostrate biopsies involve CAP. In their comparison of the Gleason system interpretation between genitourinary pathologists in the US, Jamaica, and Nigeria, Freeman, et al., came to the conclusion that the demonstrated concordance makes the use of this grading stem in international studies possible.

PSA: PSA is a contentious screening tool, but it's still a valuable metric for treatment monitoring. According to Ukoli, et al., and Igwe et al., 85.1% of patients with prostate cancer had total PSA levels above the normal cutoff level, which were determined to be 92.6 ug/l and 106 ug/l in Ibadan and Ife, respectively. The distribution of PSA in a rural Nigerian population was found to be similar to that of the unscreened US population, with greater 4 ug/l reading in 14% of men.

Prevention

A yearly PSA and nationwide cancer screening program are not yet in place. In Nigeria, checks are not frequently used. Although it is well recognized that lifestyle choices and behavioral patterns can help prevent cancer, there is a dearth of credible and timely information about Cap in Nigeria. According to Ajape, et al., the urban population of Nigeria exhibits a remarkably low level of awareness regarding prostate cancer. Worldwide awareness of prostate cancer screening and the serum PSA test is lacking. Despite this, few people were aware of prostate cancer or its risk. Oladumeji, et al., proposed that the emigration of Nigerian men to the United States has a noteworthy effect on the knowledge and beliefs about prostate cancer among native and immigrant Nigerian men, as well as their diet, alcohol and tobacco use and physical activity. Kumar, et al., found that there were enough differences to provoke deeper search. Meanwhile, reporting from Nsukka, Ejike and Ezeanyiwa suggested that life style changes in Nigerian men leading to westernized diet and use of energy sparing devices (status symbols) may lead to increase in incidence of chronic diseases like cancer.

Combination treatment

PSA level: 5-Alpha-reductase inhibitors can conceal any abnormal PSA levels because they cut the amount of PSA in your blood in half. Always let your doctor or nurse know for some men, taking a 5-alpha-reductase inhibitor and an alpha-blocker simultaneously reduces the risk of complications and relieves symptoms more effectively than taking either medication alone. Combination therapy refers to taking both medications at once. The combination treatment comes in two or one tablet form. If your symptoms interfere with your daily activities and you have a large prostate gland or a PSA level greater than 1.4 ng/ml, you might be recommended a combination treatment plan. The possibility of experiencing side effects from both medications is a drawback of combination treatment. Compared to men taking either medication alone, men receiving combination therapy are more likely to experience certain side effects, such as decreased libido, irregular ejaculation and erection issues. if you take a 5-alpha-reductase inhibitor if you have a PSA test. To determine your PSA level more precisely, they will need to double the result of your PSA test. Any increase in your PSA level should be looked into by your physician.

Other medicines: If treating your symptoms with an alpha-blocker alone isn't working, your doctor may advise you to take an anticholinergic and an alpha-blocker simultaneously. It is also possible to take an anticholinergic by itself. Alpha-blockers and anticholinergics may have similar side effects. Anticholinergics like oxybutynin, tolterodine tartrate (marketed under the name Detrusitol XL) and solifenacin succinate (marketed under the name Vesicare) are recommended as additional medications to help manage your symptoms. They may also result in other adverse effects like constipation, dry mouth and dry eyes.

Desmopressin: If you need to pass urine a lot during the night, your doctor may recommend that you take a desmopressin tablet before you go to bed. For six to eight hours, this lowers the kidneys' output of urine. Your kidney function will be monitored with routine blood tests. If you are over, desmopressin is typically not an option. A loop diuretic reduces the likelihood of needing to get up during the night by causing you to pass a lot of urine before you go to bed. You take it in the late afternoon as a capsule.

Materials and Methods

Research methodology

This study is prospective and descriptive, with a hospital setting. It's an oncological case control design.

Area of study

The government's primary facilities in Lokoja, Kogi State (FMC and specialist hospital) were included in this study. Located at coordinates 7°30′N 6°42′E, Kogi state is one of six states that make up Nigeria's North Central geopolitical zone. With a population of 3,314,043 in 2016, the state has a land area of 29,581.9 km³ and 10 other states share interstate borders with it. In 1991, the states of Kwara and Benue were combined to form Kogi state. Located at the meeting point of the Niger and Benue rivers, the capital city of Nigeria during the colonial era was Lokoja, a notable city. There, the name "Nigeria" first appeared.

Study population

The study population consisted of all men of age 40 and above attending the government owned health facilities for prostate disorder screening.

Sampling technique

A basic random sampling technique was applied to the participant selection process.

Length of study: The study was conducted over a period of twelve months. During this time, sample collected from the respondents (patients) visiting the two hospitals for prostate disorder.

Study population

The study population comprised of four hundred and forty (440) prostate disorder respondents. Two hundred and twenty (220), prostruding to Nigeria Cancer Registry.

The control group comprised of 60 non-prostrate disorder individuals who will share every characteristics of the case group except their prostate disorder status. A total of five hundred (500) participants were recruited for this study.

Inclusion criteria

Males of the age 40 and above were considered qualified and included.

Exclusion criteria

• Males below 40 was not be included.

• Inadequate samples was not included.

• Patients other than the two mentioned facilities were not included.

Administration of questionnaires

Data related to socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents and potential factors for prostatic disorder was collected by face to face interview using a pre-tested structured questionnaire after asking for and obtaining consent from the participants.

Sample collection

Veinous blood sample was collected PSA analysis on both case and control groups to determine their respective prostatic disorder status.

The processed tissue block was sectioned and stained with H and E and demonstrated with IHC markers in the morbid anatomy department for the determination of positive and negative cases.

Sample size

The sample size was determined using the formula outlined by Thrusfield as follows: n=Z2pq/d2

Where:

n=sample

size z=value for standard normal deviate=1.96

p=anticipated prevalence

q=1-p

d=Desired precision=0.05

Taking 41.4% prevalence of prostate cancer from previous similar study reported by Onoja AO, et al., 95% confidence interval (Z =1.96) and 5% margin of error (d=0.05), the initial sample size will be two hundred and tirty-four (234) as shown below.

3.8416 0.3366/0.0025=0.5840/0.0025=(1.96)2 0.414 0.813/(0.05)2=517

The final sample size was rounded up to five hundred (500) after taking into account a 5% (26 subjects) non-response rate. As a result, 440 people with prostate cancer (the case group) and sixty (60) people without prostate cancer (the control group) were recruited for the study, bringing the total number of participants to five hundred (500).

Data analysis

Data obtained was analyzed using chi-square test to compare the frequency data. The Odds Ratio (OR) was calculated for potential risk factors.

Data presentation

Analyzed data was presented using simple percentages on tables and charts.

Ethical consideration

An ethical approval was obtained from the research and ethical committee of the College of Health Sciences Prince Abubakar Audu University, Kogi state.

PSA procedures

Materials for test:

• Test cassettes

• Droppers

• Butter

• Specimen collection containers

• Centrifuge

• Timer

• 5 mls syringes

Procedure proper:

• The pouch kit or cassette was brought to room temperature (15°C-30°C) prior to testing.

• The test cassette was removed from the sealed pouch.

• The collected venous blood was centrifuged to get serum.

• With the aid of a dropper at a vertical position a drop of venipuncture (40 ul) was placed to the specimen well of the test cassette, followed by a drop of buffer (40 ul) and was timed for 5 minutes

Interpretation of results

Positive: A Test line (T) intensity equal or close to the Reference line (R) indicate a PSA level between 4 ng/ml-l0 ng/ml.

A Test line (T) A PSA level of roughly long/ml is indicated by values that are equal to or near the Reference line (R).

Negative: The Reference (R) and Control (C) regions both have color lines. In the Test line region (T), no visible color line is visible. This suggests a PSA level of less than 3ng/ml.

Procedural control: The text incorporates a procedural control. One procedural control is the emergence of cloned lines in the Reference line region (R) and Control line region (C). It attests to sufficient membrane wicking.

Tissue processing

Materials required: Tissue capsule (or cassette), automatic tissue processor (YD-14P), Hot plate (DB-11A), Tissue floating bath (XH-1001), Rotary microme (YD-355AT), 10% formalin, dehydrating solution (prepared graded of alcohol; 70%-100%). Xylene (clearing agents) and paraffin wax (impregnating media).

Procedures: The prostate tissue formerly fixed in 10% neutral buffer formalin was transferred to 10% formol saline in auto techicon processing machine for two hours before the procedures below was strictly followed:

• 10% formalin-2 hrs

• 70% alcohol-1 hr

• 80% alcohol-1 hr

• 95%b alcohol-1 hr

• Absolute alcohol-1 hr for two stages

• Xylene-1 hr for two stages

• Paraffin wax 2 hrs for two stages.

This was embedded and cool quickly.

Microtomy: The tissue block was trimmed and sectioned at 5 micron.

Staining:

• Slide section was dewaxed for 7 mins in two stages of xylene.

• The slide section was stained with Harris haematoxylin for 15 mins.

• Slide was then rinsed in tap water for 5 mins.

• Section was differentiated briefly in 1% acid alcohol.

• The slide was briefly washed in tap water.

• Section was blued with ammonium water for 2 mins.

• Slide section was washed in running tap water for 15 mins.

• Slide section was stained in eosin for 2 mins.

• Section was dehydrated in 95% and 2 stages of absolute alcohol to remove excess eosin.

• Section was cleared in xylene and mounted in DPX.

Immunohistochemistry procedures

Equipment and reagents: Dryers and oven, water bath, electronic weighing balance, -40°C refrigerator, slides and cover slippers, modified pressure cooker (115°C) for 25 minutes, xylene, prepared graded alcohol, mayers hematoxylin, Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP), citrate buffer, moist chamber container, post-primary antibodies (AMACR or P63).

• Section was deparafinized (using organic solvent, xylene) in 2 changes for 5 min each.

• Section was rehydrated in descending graded alcohols 100%, 95%, 70% and then water.

• Sections was treated to expose antigenic epitopes by heating in low pH, citrate buffer, pH 6.0.

• Citrate buffer was pre-heated in a heat resistant container placed in water in the pressure cooker for 3 min.

• Slide section was put in the pre-warm retrieval solution and lid was closed to boil for 25 min.

• Water was added gradually to the solution to cool sections.

• This was rinsed in distilled water before proceeding with staining.

• This was treated with Hydrogen peroxide for 10 min.

• Rinsed in PBS.

• This was treated with protein blocker for 10 min.

• The protein block was drained from section or wash with PBS.

• This was diluted with primary antibodies (AMACR or P504s and P63) for 45 min.

• This was rinsed thoroughly with PBS.

• This was diluted with post primary antibody for 10 min.

• HRP Polymer was applied for 10 min.

• This was rinsed with PBS and chromogenic substrate was applied for 5 min.

• This was rinsed in water.

• This was rinsed in water and counterstained with haematoxylin for 2 min

• This was rinsed in water and blued in Scott’s tap water.

• The section was dehydrate in ascending grades of alcohol, cleared in xylene and mounted in DPX mountant.

Results

Table 1 showing the total prevalence of prostate disorders in the surveyed areas (Fmc Lokoja and Kssh Lokoja).

| Respondents | No. tested | No. of disorders | % of disorders | OR | 95% CI | p-Value |

| Age | ||||||

| 40-44 | 36 | 8 | 22.2 | 0.0152 | ||

| 45-49 | 20 | 8 | 40 | |||

| 50-54 | 80 | 28 | 35 | |||

| 55-59 | 152 | 48 | 31.6 | |||

| 60-64 | 92 | 28 | 30.4 | |||

| 65-69 | 12 | 3 | 25 | |||

| 70-74 | 8 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 75-79 | 24 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 80+ | 16 | 0 | 0 | |||

Table 1: Prostate disorders in relation to their ages in the surveyed areas.

In the age grades of 40-44, 36 were involved and the number of disorders ranging from: PCA (0), BHP (1), Prostatitis (2) and normal status (5). Age 45-49-have 20 respondents with 8 numbers of disorders raging from PCA=0, BPH 20, Prostatitis 2 and normal status 6.

Age 50-54 have 80 respondents with 28 disorders ranging from PCA=0, BPH=1, Prostatitis=6 and the normal status=21. Others were 55-59. Consisting of 152, respondents, 48 disorders of PCA=3 (6.3%), BPH=5, Prostatitis=8 and the normal status=32. Age class 60-64 consisted of 92 respondents, 28 disorders of PCA=3 (10.7%), BPH=4, Prostatitis=4 and the normal=17. More so, age class of 65-69 consisted of 12 respondents with 12 disorders numbering PCA=3(100%) and the normal=9.

In the total surveyed of 440 respondents 284 were married and 76 (26.8%) of them have various disorders while 36 respondents were not married and without any disorder. 48 respondents were divorcee with 24 (50%) disorders. Those separated were 24 with 12 (50%) disorders. Widowers were 40 with 12 (30%) disorder, those co-habiting were 8 (1000) disorders.

In terms of sexual partner, 400 respondents were involved with 116 (29%) disorders, which 32 respondents were single with 8 (23%) disorders and 8 respondents were still not married but have 4 (50%) disorders. Table 2 considers several aspects of marital status and the test of association between single and married (both D, S, W, C) were 5.8812 and 0.179.

Educational status

The respondents that attended tertiary education were 208 with 48 (23.1%) disorders. Followed by those in secondary education and primary numbering 100 with 40 (40.0%) and 80 with 20 (25%) while those that have no educations and informal education were 28 with 8 (28.6%) and 16 with 8 (50.0%) disorders.

Smoking status

Respondent with smoking habits were 20 with 12 (60%) disorders and those who did not smoke where 420 with 120 (28.6%) disorders. The strength of association between non-smokers to smokers were in OD of 2.1000 to 0.5417.

Alcohol consumption

Respondents with history of alcohol were 56 with 28 (60%) disorders and those without history of alcoholic consumption were 384 with 104 (27.1%) disorders. The strength of the association between those taken alcohol and those who did not were 0.5417 and 1.6462.

Annual income

The low, middle and high income were 212, 220 and 8 with 52 (24.5%), 76 (34.5% and 4 (50.0%) of various disorders (Table 2).

| S/No | Disorders | Frequency | Percentage |

| 1 | PCA | 36 | 13.4 |

| 2 | BPH | 48 | 17.9 |

| 3 | Prostatitis | 88 | 32.8 |

| 4 | Normal | 96 | 35.8 |

| Total | 268 | 100 |

Table 2: Prostate disorders identified in the surveyed areas.

The various disorders identified in the surveyed area ranges from 36 (13.4%) prostatic carcinoma, 48 (17.9%), benign prostatic hyperplasia and 88 (32.8%). The rest, 96 (35.8%) were normal (Table 3).

| Respondents | No. tested | No. of disorders | % of disorders |

| Age | |||

| 40–44 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 45–49 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 50–54 | 8 | 2 | 25 |

| 55–59 | 22 | 8 | 36.4 |

| 60–64 | 14 | 0 | 0 |

| 65–69 | 6 | 2 | 33.3 |

| 70–74 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 75–79 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| 80+ | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Married | 30 | 4 | 13.3 |

| Divorced | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Separated | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Widower | 8 | 2 | 25 |

| Co-habiting | 4 | 4 | 100 |

| No. sexual partner | |||

| Multiple | 36 | 10 | 27.8 |

| Single | 16 | 0 | 0 |

| None | 8 | 2 | 25 |

| Sexual enhancer | |||

| Orthodox | 20 | 2 | 10 |

| Concoction | 22 | 10 | 45.5 |

| None | 18 | 0 | 0 |

| Stds history | |||

| Yes | 20 | 6 | 30 |

| No | 40 | 6 | 15 |

| Nationality | |||

| Nigerian | 56 | 10 | 17.9 |

| Non-Nigerian | 4 | 2 | 50 |

| Occupation | |||

| Unemployed | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Civil servant | 12 | 6 | 50 |

| Business | 26 | 2 | 7.7 |

| Artisans | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Farmers | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Students | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Retiree | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Priest | 6 | 4 | 66.7 |

| Educational status | |||

| None | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Informal | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Primary | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| Secondary | 16 | 4 | 25 |

| Tertiary | 24 | 8 | 33.3 |

| Smoking status | |||

| Smoking | 10 | 2 | 20 |

| Non smoking | 50 | 10 | 20 |

| Alcohol consumption | |||

| Yes | 6 | 2 | 33.3 |

| No | 54 | 10 | 18.5 |

| Exercise | |||

| Yes | 36 | 12 | 33.3 |

| No | 24 | 0 | 0 |

| Annual income | |||

| Low | 34 | 4 | 11.8 |

| Middle high | 20 | 2 | 10 |

| High | 6 | 6 | 100 |

| Prostate status | |||

| Control | 24 | 6 | 25 |

Table 3: Control for the study areas.

Control for the study areas

Among the statutorily known respondents for control, 30 were married while 4 were single. Others were: Divorced (6), separated (2), widower (8) and co-habiting (4).

No of sexual partner

Those with multiple partners were 36 with 10 (27.8%) mild disorder. Those with single partners were 16 with (0%) disorder. Those without partner were 8 with 2 (25.0%) disorders.

Sexual enhancer

Those using orthodox and concoction were 20 with 2. (10.0) and 22 with 10 (45.5%) respectively. While 18 with 0 (0.0%) were free from sexual booster.

STD’s History

Among the control, 20 have the history of STDs while 40 were free from Stds.

Nationality

Nigerians were dominant in the control group and where merely business men. While majority of them (24) attended tertiary institution.

Smoking

Only 10 respondents with 2 (20.0%) disorders smoked.

Alcoholic consumption

Only 6 respondents with 2 (33.3%) disorder took alcohol.

Prostate status in control group

16 of the control groups were having PSA>4 ng/ml while 44 of them were normal.

Prostate disorder in relation to their marital status

Out of forty four (44) single individual having their PSA normal, other categories ranging from MDSWC were 30 with 4 (13.3%), 6 with 0 (0.0%), 2 with 0 (0.0%), 8 with 2 (25%) and 4 with 4 (100%) (Tables 4-9).

| S/No | Disorders | Frequency | Percentage |

| 1 | PSA ≥ 4 ng/ml | 16 | 26.7 |

| 2 | Normal | 44 | 73.3 |

| Total | 60 | 100 |

Table 4: Disorders identified in control for the study areas.

| Age | No. tested | No. of disorders | % of disorders | OR | 95% CI | P-value |

| 40–44 | 16 | 4 | 25 | 0.0202 | ||

| 45–49 | 8 | 4 | 50 | |||

| 50–54 | 40 | 12 | 30 | |||

| 55–59 | 84 | 28 | 33.3 | |||

| 60–64 | 44 | 12 | 27.3 | |||

| 65–69 | 4 | 4 | 100 | |||

| 70–74 | 4 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 75–79 | 12 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 80+ | 8 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0.2071 | ||

| Married | 152 | 40 | 26.3 | |||

| Divorced | 16 | 8 | 50 | |||

| Separated | 12 | 4 | 33.3 | |||

| Widower | 20 | 8 | 40 | |||

| Co-habiting | 4 | 4 | 100 | |||

| No. sexual partner | ||||||

| Multiple | 216 | 64 | 29.6 | |||

| Single | 4 | 0 | 0 | |||

| None | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Sexual enhancer | ||||||

| Orthodox/concoction | 40 | 16 | 40 | 0.6667 | 0.3 | |

| None | 180 | 48 | 26.7 | 1.5 | ||

| Stds history | ||||||

| Yes | 144 | 44 | 30.6 | 0.8612 | 0.6910-1.2710 | 0.175 |

| No | 76 | 20 | 26.3 | 1.1611 | 0.7868-1.4471 | |

| Nationality | ||||||

| Nigerian | 220 | 64 | 29.1 | 0.5 | ||

| Non-Nigerian | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Occupation | ||||||

| Unemployed | 20 | 8 | 40 | 0.0109 | ||

| Civil servant | 56 | 12 | 21.4 | |||

| Business | 76 | 32 | 42.1 | |||

| Artisans | 12 | 8 | 66.7 | |||

| Farmers | 16 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Students | 12 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Retirer | 24 | 4 | 16.7 | |||

| Priest | 4 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Educational status | ||||||

| None | 16 | 4 | 25 | 0.0677 | ||

| Informal | 8 | 4 | 50 | |||

| Primary | 40 | 12 | 30 | |||

| Secondary | 56 | 20 | 35.7 | |||

| Tertiary | 96 | 20 | 20.8 | |||

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Smoking | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | ||

| Non smoking | 220 | 64 | 29.1 | |||

| Alcohol consumption | ||||||

| Yes | 20 | 8 | 40 | 0.7 | 0.5490–1.3363 | 0.4471 |

| No | 200 | 56 | 28 | 1.4286 | 0.7483– 1.8216 | |

| Exercise | ||||||

| Yes | 152 | 36 | 23.7 | 1.6889 | 0.9260– 1.7024 | 0.3084 |

| No | 60 | 24 | 40 | 0.5921 | 0.5874– 1.0799 | |

| Annual income | ||||||

| Low | 112 | 28 | 25 | 0.1859 | ||

| Middle high | 108 | 36 | 33.3 | |||

| High | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Prostate status | ||||||

| Case | 220 | 64 | 29.1 | 0.6875 | 0.5316– 1.3587 | 0.4028 |

| Control | 30 | 6 | 20 | 1.4545 | 0.7360– 1.8813 | |

Table 5: Showing the total prevalence of prostate disorders in FMC Lokoja.

| S/No | Disorders | Frequency | Percentage |

| 1 | PCA | 16 | 12.1 |

| 2 | BPH | 24 | 18.2 |

| 3 | Prostatitis | 44 | 33.3 |

| 4 | Normal | 48 | 36.4 |

| Total | 132 | 100 |

Table 6: Prostate disorder identified in FMC Lokoja.

| Respondents | No. tested | No. of disorders | % of disorders |

| Age | |||

| 40–44 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 45–49 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 50–54 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| 55–59 | 14 | 6 | 42.9 |

| 60–64 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| 65–69 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 70–74 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 75–79 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| 80+ | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Married | 16 | 2 | 12.5 |

| Divorced | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Separated | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Widower | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Co-habiting | 2 | 2 | 100 |

| No. sexual partner | |||

| Multiple | 18 | 4 | 22.2 |

| Single | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| None | 6 | 2 | 33.3 |

| Sexual enhancer | |||

| Orthodox | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Concoction | 12 | 6 | 50 |

| None | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| Stds history | |||

| Yes | 10 | 2 | 20 |

| No | 20 | 4 | 20 |

| Nationality | |||

| Nigerian | 30 | 6 | 20 |

| Non-Nigerian | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Occupation | |||

| Unemployed | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Civil servant | 6 | 4 | 66.7 |

| Business | 14 | 0 | 0 |

| Artisans | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Farmers | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Students | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Retiree | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Priest | 2 | 2 | 100 |

| Educational status | |||

| None | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Informal | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Primary | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Secondary | 8 | 2 | 25 |

| Tertiary | 10 | 4 | 40 |

| Smoking status | |||

| Smoking | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Non smoking | 26 | 6 | 23.1 |

| Alcohol consumption | |||

| Yes | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| No | 28 | 6 | 21.4 |

| Exercise | |||

| Yes | 18 | 6 | 33.3 |

| No | 12 | 0 | 0 |

| Annual income | |||

| Low | 20 | 2 | 10 |

| Middle high | 8 | 2 | 25 |

| High | 2 | 2 | 100 |

| Prostate status | 30 | 6 | 20 |

Table 7: Control for FMC Lokoja.

| S/No | Disorders | Frequency | Percentage |

| 1 | Psa ≥ 4ng/ml | 2 | 6.7 |

| 2 | Normal | 28 | 93.3 |

| Total | 30 | 100 |

Table 8: Disorders identified in control for FMC Lokoja.

| Age group | No. tested | No of disorders | PCA | Age group | Prostatitis | Normal |

| 40–44 | 36 | 8 | 0 | 40–44 | 6 | 28 |

| 45–49 | 20 | 8 | 0 | 45–49 | 5 | 12 |

| 50–54 | 80 | 28 | 0 | 50–54 | 17 | 52 |

| 55–59 | 152 | 48 | 3 | 55–59 | 30 | 84 |

| 60–64 | 92 | 28 | 3 | 60–64 | 12 | 64 |

| 65–69 | 12 | 3 | 3 | 65–69 | 0 | 9 |

| 70–74 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 70–74 | 0 | 0 |

| 75–79 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 75–79 | 0 | 0 |

| 80+ | 16 | 0 | 0 | 80+ | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 440 | 123 | 9 | Total | 70 | 249 |

Table 9: Prostate disorders in relation to their ages in the surveyed areas.

Prostate disorders in relation to their ages in the surveyed areas

In the age grades of 40-44, 36 were involved and the number of disorders ranging from: PCA (0), (BHP (1), Prostatitis (2) and normal status (5). Age 45-49-have 20 respondents with 8 numbers of disorders raging from PCA=0, BPH 20, Prostatitis 2 and normal status 6.

Age 50-54 have 80 respondents with 28 disorders ranging from PCA=0, BPH=1, prostatitis=6 and the normal status=21. Others were 55-59. Consisting of 152, respondents, 48 disorders of PCA=3 (6.3%), BPH=5, Prostatitis=8 and the normal status=32. Age class 60-64 consisted of 92 respondents, 28 disorders of PCA=3 (10.7%), BPH=4, Prostatitis=4 and the normal=17. More so, age class of 65-69 consisted of 12 respondents with 12 disorders numbering PCA=3(100%) and the normal=9.

Other age classes of 70-74, 75-79 and 80 above consisted of 8, 24. And 16 respondent but no disorder was recorded (Table 10).

| Marital status | No. tested | No. of disorders | PCA | BPH | Prostatitis | Normal |

| Single | 36 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Married | 284 | 76 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 59 |

| Divorced | 48 | 24 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 18 |

| Separated | 24 | 12 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 10 |

| Widower | 40 | 12 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 5 |

| Co-habiting | 8 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| Total | 440 | 132 | 9 | 10 | 13 | 100 |

Table 10: Prostate disorder in relation to their marital status in the surveyed areas.

In the surveyed area of Lokoja metropolis, 284 respondents were married with 76 disorders ranging from PCA=5, BPH=5, prostatitis=7, while the single (unmarried) respondents where 36 and without records of any disorder. However, the divorcee were 48 respondents with 24 of various disorders ranging from PCA=2, BPH=2, prostatitis=2. The separated and widower were 24 and 40 respondents recorded one (1) PCA each simultaneously, and those co-habiting were 8 and have no history of any disorder (Table 11).

| Sexual enhancers | No. tested | No. of disorders | PCA | BPH | Prostatitis | Normal |

| Orthodox | 40 | 16 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 10 |

| Concoction | 56 | 32 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 22 |

| None | 344 | 84 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 64 |

| Total | 440 | 132 | 9 | 12 | 15 | 96 |

Table 11: Prostate disorder in relation to sexual enhancer in the surveyed areas.

Prostate disorder in the surveyed area: Among those using sexual enhancer, 40 respondents were indulged in orthodox and two (2) out of them were diagnosed for PCA, and those indulged in concoction were 56 respondents and three were PCA positive and 344 respondents remained natural, without enhancer and four (4) were diagnosed PCA positive (Table 12).

| No. of sexual partners | No. tested | No. of disorders | PCA | BPH | Prostatitis | Normal |

| Multiple | 400 | 116 | 8 | 11 | 11 | 86 |

| One partner | 32 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 5 |

| None | 8 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Total | 440 | 132 | 9 | 11 | 14 | 94 |

Table 12: Prostate disorder in relation to number of sex partner(s) in the surveyed areas.

Prostate disorder in relation to number of sex partner(s) showed that 400 respondents were involved in multiple sex with 116 of them having various disorders and eight (8) out of them were diagnosed PCA positive. Out of thirty two (32) respondents that maintained single partner, only one (1) was diagnosed PCA positive and those who have not married at all were 8 and have no history of PCA (Table 13).

| History of STDs | No. tested | No. of disorders | PCA | BPH | Prostatitis | Normal |

| Yes | 296 | 88 | 3 | 9 | 11 | 65 |

| No | 144 | 44 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 32 |

| Total | 440 | 132 | 9 | 11 | 15 | 97 |

Table 13: Prostate disorder in relation to sexually transmitted diseases in the surveyed areas.

Prostate disorder in relation to sexually transmitted diseases in the surveyed areas: Out of 296 respondents who had history of sexually transmitted diseases (stds) three (3) were positive for PCA, while 144 respondents who had no history of STDS produced (6) six PCA.

Staining techniques for the detection of prostate disorders

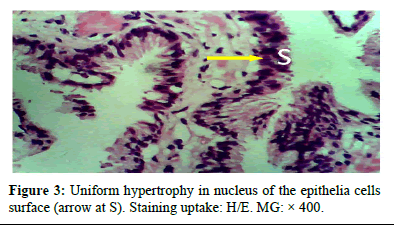

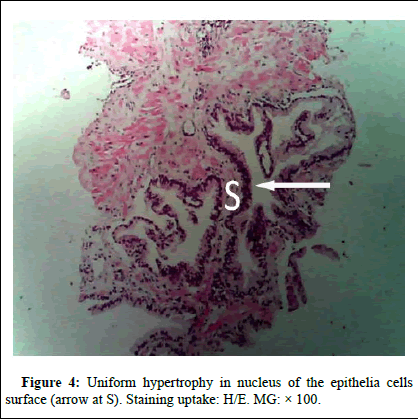

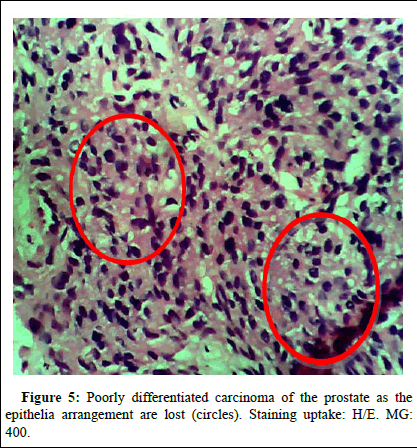

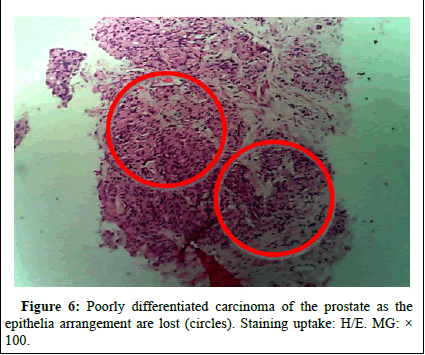

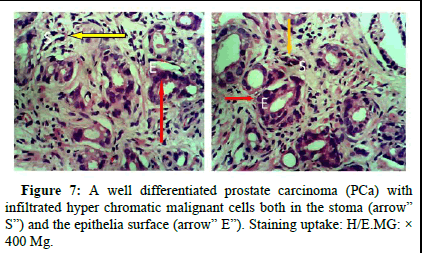

Hematozylin and eosin staining: The below figures shows different Hematozylin and eosin stainings (Figures 3-7).

Figure 3: Uniform hypertrophy in nucleus of the epithelia cells surface (arrow at S). Staining uptake: H/E. MG: 400.

Figure 4: Uniform hypertrophy in nucleus of the epithelia cells surface (arrow at S). Staining uptake: H/E. MG: 100.

Figure 5: Poorly differentiated carcinoma of the prostate as the epithelia arrangement are lost (circles). Staining uptake: H/E. MG: 400.

Figure 6: Poorly differentiated carcinoma of the prostate as the epithelia arrangement are lost (circles). Staining uptake: H/E. MG: 100.

Figure 7: A well differentiated prostate carcinoma (PCa) with infiltrated hyper chromatic malignant cells both in the stoma (arrow” S”) and the epithelia surface (arrow” E”). Staining uptake: H/E.MG: 400 Mg.

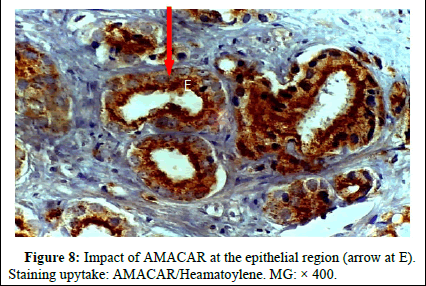

Immunohistochemical staining (AMACAR and P63 as markers)

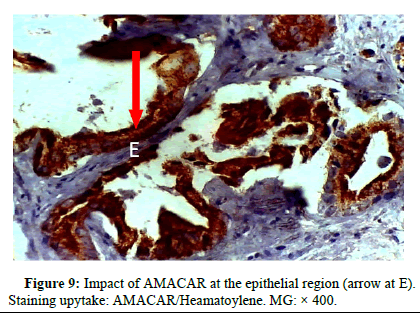

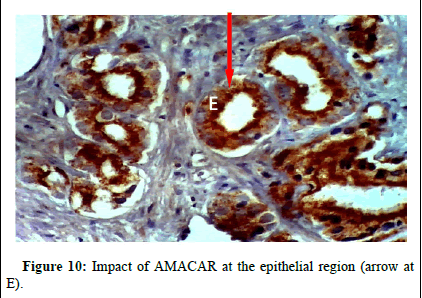

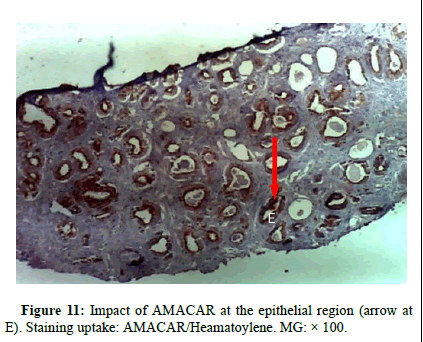

Amacar staining in well differentiated Prostate Cancer (PCa): Diagnostic method the enzyme alpha-methylacyl-CoA racemase, or p504S, belongs to the isomerases family and is involved in the production of bile acids and the metabolism of branched-chain fatty acids. It is expressed in both normal and malignant cells' mitochondria and peroxisomes. In comparison to benign prostatic glands, P504S is overexpressed in prostatic carcinoma (Figures 8-11). Nuclear staining is exhibited by the myoepithelial marker P63. Below is a picture of the p504s and p63 immunohistochemical stain:

Figure 8: Impact of AMACAR at the epithelial region (arrow at E). Staining upytake: AMACAR/Heamatoylene. MG: 400.

Figure 9: Impact of AMACAR at the epithelial region (arrow at E). Staining upytake: AMACAR/Heamatoylene. MG: 400.

Figure 10: Impact of AMACAR at the epithelial region (arrow at E).

Figure 11: Impact of AMACAR at the epithelial region (arrow at E). Staining uptake: AMACAR/Heamatoylene. MG: 100.

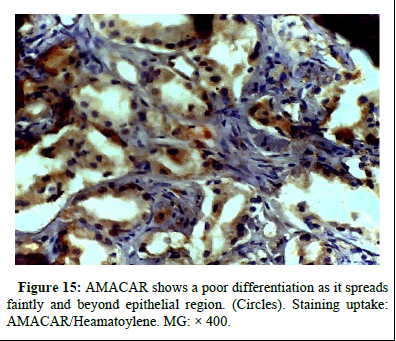

Amacar staining in poorly differentiated cap

Figures 12-15 shows poor differentiation as it spreads faintly and beyond epithelial region.

Figure 12: AMACAR shows a poor differentiation as it spreads faintly and beyond epithelial region. (Circle). Staining uptake: AMACAR/Heamatoylene. MG: 400.

Figure 13: AMACAR shows a poor differentiation as it spreads faintly and tt the stroma region. (Circle). Staining uptake: AMACAR/Hematoylene. MG: 400.

Figure 14: AMACAR shows a poor differentiation as it spreads faintly and beyond epithelial region. (Circles). Staining uptake: AMACAR/Heamatoylene. MG: 400

Figure 15: AMACAR shows a poor differentiation as it spreads faintly and beyond epithelial region. (Circles). Staining uptake: AMACAR/Heamatoylene. MG: X 400.

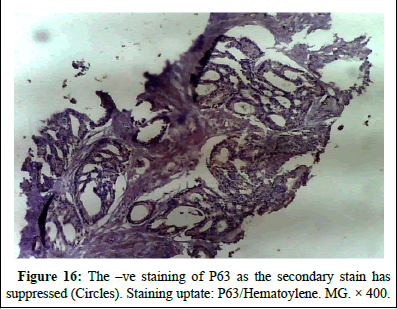

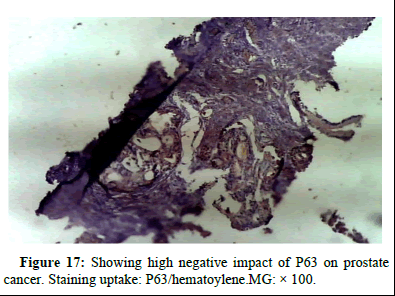

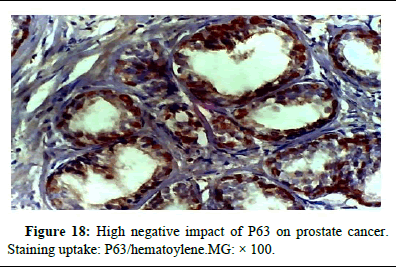

P63 as a negative staining in prostate cancer (CAP)

Figures 16-18 shows the negative impact of p63 on prostate cancer.

Figure 16: The –ve staining of P63 as the secondary stain has suppressed (Circles). Staining uptate: P63/Hematoylene. MG. × 400.

Figure 17: Showing high negative impact of P63 on prostate cancer. Staining uptake: P63/hematoylene.MG: ×100.

Figure 18: High negative impact of P63 on prostate cancer. Staining uptake: P63/hematoylene.MG: × 100.

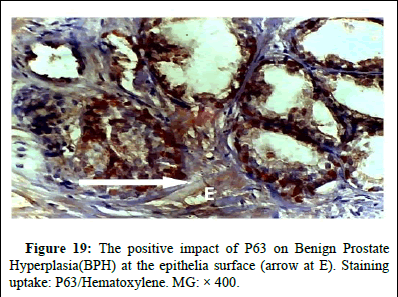

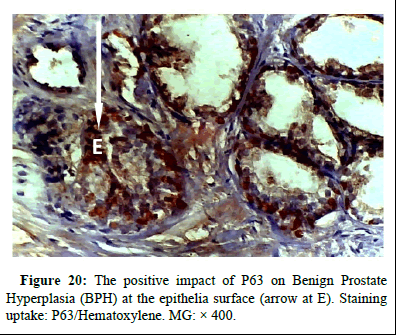

P63 positive staining in BPH

Figures 19 and 20 shows the P63 positive staining in BPH.

Figure 19: The positive impact of P63 on Benign Prostate Hyperplasia(BPH) at the epithelia surface (arrow at E). Staining uptake: P63/Hematoxylene. MG: × 400.

Figure 20: The positive impact of P63 on Benign Prostate Hyperplasia(BPH) at the epithelia surface (arrow at E). Staining uptake: P63/Hematoxylene. MG: × 400.

From the Table 14, alhpa-methylacyl coA racemase showed a strong positive for prostatic cancer and negative for benign prostatic hyperplasia. Whereas, P63 demonstrated an affinity for benign prostate hyperplasia and remain negative for prostatic cancer.

| Markers | BPH | CAP | Pattern |

| AMARC R | -ve | +ve | Nuclear |

| P63 | +ve | -ve | Nuclear |

Table 14: The summary of the expression patterns of the tumor markers used.

Discussion

It has been reviewed in the majority of research conducted thus far that prostate cancer incidence is more prevalent among the individuals between the ages of 40 and 80. The presence work has reviewed that age is a strong determinant in promoting prostrate disorders as it gradually increases in accordance with age. At 40–54, no prostate cancer was detected, 55–59 shows prevalence of 6.3%, 60–64 records 10.7%, and this picked at 65–69 with 100% prevalence of these disorders. However, the work shows a sharp declination of PCa not present among the age of 70–80 and above. This finding aligns with the hypothesis put forth by Morounke, et al., regarding the role of age related risk factors for certain cancers, such as alterations in the estrogen androgen ratio that may stimulate aberrant prostate growth. In marital status, the strength of association of being single with Odd Ratio (OD) 5.8812 is relatively high compare to married men of various categories (DSWC) with Odd Ratio (OR) 0.1700. This suggests that marital status has a significant impact, as supported by Schiffmann's 2015 research. However, in contrast to Newell, et al., and King, et al., research has shown that men without children may be more likely to develop prostate cancer than married men, although the consistency of these findings has not been established because Newell, et al., refuted these findings. The findings of Giles et al., which showed that a lower ejaculatory output in otherwise healthy men is linked to a higher risk of prostate cancer, particularly in early adulthood, provided additional support for this theory. Doolan, et al.'s findings also showed that men Therefore, having multiple or single partner may not really count a chance of having prostate cancer as the strength of the association is weak.

Conversely, the use of enhancer has shown the strength of association between those who used enhancer (orthodox or concoction) and those who did not indulge in either have odd ratio of 0.4884 and 2.0476. This has implied that the use of any type of enhancer may lead to a reduction in prostate cancer.

STds: Surprisingly, six (6) respondents out of 144 of those who did not have history of stds have 6 PCa, while those with history of stds have 3 PCa out of 296 respondents in the surveyed area. This is an indication that stds may not have been the determinant or a strong predisposing factors. Contrary to this, some studies have found that there is a significant relationship between the incidence of stds and the incidence of PCa. These have assumed the fact that sexual behavior and associated exposure to infectious agents increases the risk of PCa. The dominant groups of respondents recorded more of prostatic cancer (8 PCa) were those with multiple partners while those with single wife recorded only 1 PCa and who were not marry did not have (PCa) in this work.

However, the overall percentage prevalence of prostatic cancer in this work is 13.4% and wile in the control group only 16 out of 60 respondents asymptomatically showed a high PSA 4 ng/ml and above [17].

Conclusion

Alphamethylacyl CoA racemase used as a marker has proven the discrimination beyond doubt as it was clearly positive for Pca and negative for BPH. Whereas, P63 marker showed negative for Pca and strong affinity for Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH).

Contrary to other similar works, marital status is a strong determinant to prostatic disorders as test of association between married respondents ranging from the categories of marriages (MDSWC) and single (unmarried) respondents showed a strong indication. Therefore caution should be taken on polygamous or multiple partners as it has shown a conduit for Prostate Cancer (PCa). People above forty five (45) should go for clinical examination including the test for prostate specific antigen level. Finally, the use of alph methylacetyl coA racemase in immunohistochemistry should be encouraged.

References

- Abouassaly R, Thompson IM, Platz EA, Klein EA (2012) Epidemiology, etiology, and prevention of prostate cancer. Campbell-Walsh Urol 10: 2704.

- Badmus TA, Adesunkanmi AR, Yusuf BM, Oseni GO, Eziyi AK, et al. (2010) Burden of prostate cancer in southwestern Nigeria. Urol 76: 412-416.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Afolayan EA (2004) Five years of cancer registration at Zaria (1992-1996). Niger Postgrad Med J 11: 225-229.

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ajape AA, Babata A, Abiola OO (2010) Knowledge of prostate cancer screening among native African urban population in Nigeria. Pub Health 1.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Akang EE, Aligbe JU, Olisa EG (1996) Prostatic tumours in Benin city, Nigeria. West Afr J Med 15: 56-60.

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Akwu PB, Shaibu GO, Omotoso OD (2019) Utilization of Prostate Serum Antigen (PSA) screening services among the Igala people of North Central Nigeria. J Hum Anat Physiol 3: 5.

- Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, et al. (2008) Molecular biology of the cell. Ann Bot 91: 401.

- Ames BN, Kammen HO, Yamasaki E (1975) Hair dyes are mutagenic: Identification of a variety of mutagenic ingredients. Proc Natl Acad Sci 72: 2423-2427.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Badmus TA, Adesunkanmi AR, Yusuf BM, Oseni GO, Eziyi AK, et al. (2010) Burden of prostate cancer in Southwestern Nigeria. Urol 76: 412-416.

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Barrett-Connor E, Garland C, McPhillips JB, Khaw KT, Wingard DL (1990) A prospective, population based study of androstenedione, estrogens, and prostatic cancer. Cancer Res 50: 169-173.

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bashir MN (2015) Epidemiology of prostate cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 16: 5137-5141.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bergh J, Marklund I, Thellenberg-Karlsson C, Gronberg H, Elgh F, et al. (2007) Detection of Escherichia coli 16S RNA and cytotoxic necrotizing factor 1 gene in benign prostate hyperplasia. European Urol 51: 457-463.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Binu VS, Chandrashekhar TS, Subba SH, Jacob S, Kakria A, et al. (2007) Cancer pattern in Western Nepal: A hospital based retrospective study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 8: 183.

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bosland MC (2013) A perspective on the role of estrogen in hormone induced prostate carcinogenesis. Cancer Lett 334: 28-33.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Caini S, Gandini S, Dudas M, Bremer V, Severi E, et al. (2014) Sexually transmitted infections and prostate cancer risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol 38: 329-338.

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Calle EE, Kaaks R (2004) Overweight, obesity and cancer: Epidemiological evidence and proposed mechanisms. Nat Rev Cancer 4: 579-591.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Center MM, Jemal A, Lortet-Tieulent J, Ward E, Ferlay J, et al. (2012) International variation in prostate cancer incidence and mortality rates. European Urol 61: 1079-1092.

Citation: Ude NA (2025) Prostate Disorders and its Evaluation in Relation to Marital Status Among Male of 40 Years and above Attending tertiary Health Facilities Lokoja, Kogi State (2022). Occup Med Health 13: 568.

Copyright: © 2025 Ude NA. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Usage

- Total views: 233

- [From(publication date): 0-0 - Dec 11, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 157

- PDF downloads: 76