Recruitment and Retention in mhealth Interventions for Addiction and Problematic Substance Use: A Systematic Review

Received: 18-Sep-2023 / Manuscript No. jart-23-117788 / Editor assigned: 20-Sep-2023 / PreQC No. jart-23-117788 / Reviewed: 04-Oct-2023 / QC No. jart-23-117788 / Revised: 09-Oct-2023 / Manuscript No. jart-23-117788 / Accepted Date: 15-Nov-2023 / Published Date: 16-Oct-2023 QI No. / jart-23-117788

Abstract

Background: Disordered and problematic addictions are significant public health issues. It has been proposed that mHealth interventions can provide new models and intervention delivery modalities. However, research shows that studies that evaluate mHealth interventions for addiction disorders have low recruitment and high attrition. This study aims to identify published peer-reviewed literature on the recruitment and retention of participants in studies of mHealth interventions for people with addiction or problematic use and to identify successful recruitment and retention strategies.

Methods: Relevant studies were identified through Medline, Embase, PsychINFO, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) after January 1998. Studies were limited to peer-reviewed literature and English language published up to 2023. The revised Cochrane Risk of Bias RoB 2 tool was used to assess the risk of bias.

Results: Of the 2135 articles found, 60 met the inclusion criteria and were included. The majority of studies were for smoking cessation. Only three studies retained 95% of participants at the longest follow-up, with ten studies retaining less than 80% at the longest follow-up, indicating a high risk of retention bias. Those studies with high retention rates used a variety of recruitment modalities; however, they also recruited from populations already partially engaged with health support services rather than those not accessing services.

Conclusions: This review of recruitment and retention outcomes with mHealth interventions highlights the need for multimodal recruitment methods. However, significant gaps in effective engagement and retention strategies limit the positive outcomes expected from mHealth interventions.

Keywords

Addiction disorders; Substance abuse; mHealth interventions; mHealth recruitment strategies; Retention

Background

Addiction disorders and problematic substance use are significant public health problems, requiring a cross-disciplinary and multi-level action approach to effective interventions. The prevalence of addictive disorders and problematic substance use varies by the substance or Behaviour of concern and across population groups. For example, international standardized prevalence rates of gambling disorders range from 0.5% to 7.6%, with an average rate across all countries of 2.3% [1]. While the global prevalence of alcohol use disorders is estimated at 8.6% (95% Confidence Interval (CI) 8.1-9.1) in men and 1.7% (95% CI 1.6-1.9) in women [2 ].

Age-standardized prevalence of dependent cannabis use is 3.5% [3] and an estimated 22% of the global population smoke tobacco daily and 0.77% use amphetamines daily [4]. The misuse and abuse of drugs contribute significantly to the global burden of disease. For example, 4.2% (3.7-4.6) of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) are attributable to alcohol use. Despite the disease burden and individual harms experienced, and irrespective of the disorder, many people with gambling or substance use disorders are not receiving treatment. Access is a major barrier to care, especially when treatment interventions are primarily delivered face-to-face [5 ,6]. Financial issues can also be a barrier to treatment; for example, a USA survey of 9000 people with mental health and substance use disorders reported that 15% of respondents did not seek help at all and 17% left treatment early due to financial costs [7] Geographic location has also been found to be a barrier where people living in rural locations have less service provision or fewer choices than their urban counterparts [8]. Other barriers to seeking and receiving help include reports of a feeling of shame or stigma as well as a fear of government agencies [9]. Cultural appropriateness of services delivered and innate racial bias have also been reported as barriers [10]. As a result, significant proportions are without treatment or flexible treatment options [11 ,12].

mHealth interventions have been suggested as an alternative to overcome many barriers that deter individuals from seeking help. mHealth interventions are typically shorter and found to be more costeffective, enable immediate treatment access, and have a greater and more diverse reach than analogue interventions [13] Thus, they have the potential to reach a more significant number of those in need of help than traditional intervention models.

mHealth tools

mHealth is a catchall term that encompasses and refers to the many different capabilities of mobile phone technology, such as talking,texting, on and offline internet content and sensors within or tethered to mobile phones and applies them to health across the continuum [14].

Smartphone applications (apps) are among the more common mHealth tools developed for health interventions. Many have been designed and developed to support self-management and behaviour change for smoking cessation [15 ] cardiac rehabilitation, 16 healthy lifestyles [16 ], Diabetes [17 ], Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) [18] nutrition [19 ] mental illness [20] and even youth driving [21] mHealth interventions designed and developed using good evidence collectively show promise [22], and mHealth and app use is growing in other health domains, including other forms of addiction and problematic substance use [23] However, relatively few mHealth interventions regarding problem, disordered or harmful gambling have been developed. In contrast, in alcohol and substance misuse, many of the apps that have been developed are not based on empirically supported interventions, have not been empirically tested and are often not readily available [24] This lack of evidence can lead to unintended negative consequences, such as delaying help-seeking or promoting information inconsistent with current health advice [25] However, apps that have been evaluated, such as those for alcohol Step Away A-CHESS [26] Promillekol [27] and SMS programmer with and without web-based support or feedback, [28-30] have been found effective in reducing substance use long-term. SMS aftercare programmes have also been evaluated in adults discharged from rehabilitation facilities [31] and to help adults reduce marijuana use [32].

Recruiting hard-to-reach populations

mHealth tools can potentially reach more hard-to-reach populations, such as those with comorbid mental health or substance use disorder and marginalized groups. In smoking cessation trials, retention of participants with mental health or substance use disorders or problematic substance use can be poor compared to other population groups [33,34] with some trials losing more than twothirds of their participants at follow-up. In general, people of colour, people from minority groups, and those from lower socioeconomic groups are underrepresented as research participants in clinical trials despite often having an increased disease burden due to socioeconomic determinants of health [35,36].

In 2019 it was estimated that 5 billion people worldwide had mobile devices, over half of which were smartphone [37]. In parallel, mobile technology has been proliferating. New capabilities such as GPS, augmented and virtual reality, wearable and implantable sensors, and biometric authentication are difficult to ignore. These capabilities have highlighted the role mobile devices such as smartphones can play in the addiction intervention space.

Rationale

This systematic review aimed to identify published peer-reviewed literature on the recruitment and retention of participants in studies of mHealth interventions for people with addiction and/or problematic substance use and to identify successful recruitment strategies. This systematic review focuses on different types of addictive disorders or problematic substance use, such as gambling, tobacco, problematic drinking and the use of these addictive substances.

Methods

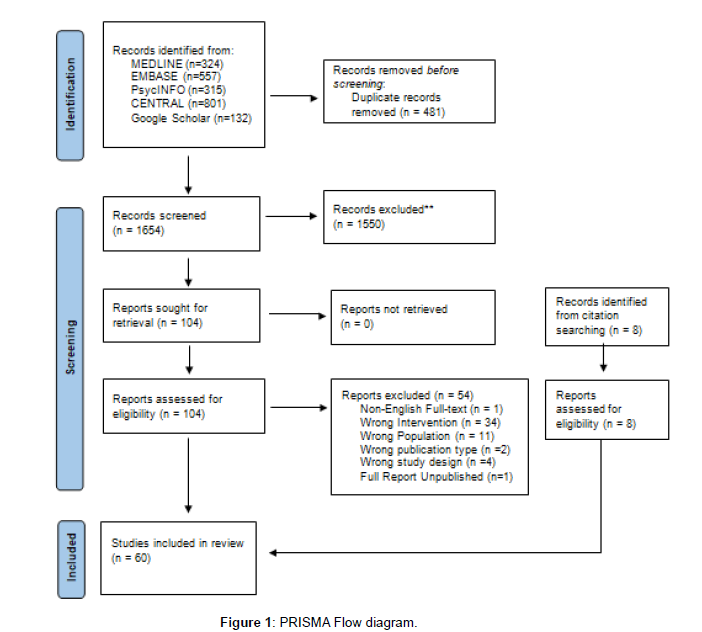

We conducted a systematic review following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [38] the review protocol was prospectively registered with PROSPERO (CRD 42021279724).

Search strategy

We conducted an electronic search of Medline, Embase, PsychINFO, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL). Search terms combined addiction-related terms with mHealth, treatment terms, participant recruitment and retention (see Appendix 1). An electronic search using Google Scholar to check for missed publications (limited to the first 200 results) was also conducted.

We limited the search to peer review literature and English language abstracts or text. Our search was limited to publications after January 1998, when text messaging became mainstream. All searches were conducted up until 02 August 2023.

In addition to our database search, we hand-searched the references of eligible publications for additional references.

Screening and data extraction

All search results were exported to Rayyan.ai, and duplicates were removed automatically. Titles and abstracts were screened independently by two authors (BK and JCM) against the screening criteria for potential relevance (Table 1). Only results papers were included, although protocol papers, lessons learned, and formative papers could be included as sources of additional information if the results paper was also included. Any disagreements between reviewers were resolved by a third reviewer (GH).

| Criteria | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Study design | RCT, cluster-RCT, quasi-RCT, and non- randomized controlled trials | Studies without a control arm Observational studies |

| Participants | Adults (18 years or older) with:

|

Mobile phone, social media, and internet addiction |

| Setting | No limits are placed on setting | |

| Intervention | Any mHealth intervention to manage addiction or problematic substance use, including: smartphone apps, text or SMS programmes, programmes explicitly using smartphone technology as part of an intervention. | Interventions not primarily delivered via a mobile device |

| Control | No limits on the type of control | No control arm |

| Outcome | No limits on outcome measured |

Table 1:Study inclusion criteria.

We retrieved the full-text articles of all relevant articles for further screening by both reviewers. All articles that were not excluded were imported to NVivo for data extraction.

Study quality

For all RCTs, the ROB-2 assessment [39] was conducted by one reviewer (BK or AO) (Table 2). For all non-randomized and quasirandomized studies, ROBINs-I [40] was used to evaluate quality (Table 3). A second reviewer (JM) assessed 20% of included studies. Any disagreements in the scoring between reviewers were resolved by discussion. If disagreements were unresolved by discussion, they were arbitrated (GH).

| Authors, Year | Criteria | Overall Bias | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomization process | Deviations from intended interventions | Missing outcome data | Measurement of the outcome | Selection of the reported result | ||

| Abroms 201441 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns | Some concerns |

| Abroms 201742 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns | Some concerns |

| Affret 202043 | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns |

| Agyapong 201228 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns | Some concerns |

| Agyapong 201844 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns | Some concerns |

| Aigner 201745 | Some concerns | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns | Some concerns |

| Asayut 2022 | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns | Low risk | Some concerns | Some concerns |

| Bindhim 201815 | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns | Low risk | Some concerns | Some concerns |

| Bricker 201446 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Bricker 202047 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns | Some concerns |

| Chen 202048 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Cheung 201549 | High risk | Some concerns | Some concerns | Low risk | Some concerns | High risk |

| Demartini 201850 | Low risk | Some concerns | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns |

| Destasio 201851 | Some concerns | Some concerns | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns | Some concerns |

| Farren 2022 | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns |

| Forinash 201852 | Low risk | Some concerns | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns | Some concerns |

| García Pazo 2021 | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Low risk | Some concerns | Some concerns |

| Goldenhersch 202053 | Low risk | Some concerns | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | High risk |

| Graham 202054 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Graham 202155 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Gustafson 201456 | Low risk | Some concerns | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Haug 201757 | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Hébert 202058 | Low risk | Some concerns | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns | Some concerns |

| Hicks 201759 | Some concerns | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | High risk |

| Hides 201860 | Some concerns | Some concerns | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | High risk |

| Hoeppner 201761 | High risk | Some concerns | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns | High risk |

| Keoleian 201362 | High risk | Some concerns | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns | High risk |

| Liang 201863 | Some concerns | Some concerns | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns | Some concerns |

| Lucht 202164 | Some concerns | Some concerns | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns | Some concerns |

| Masaki 202065 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Mason 201466 | Some concerns | Some concerns | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | Some concerns |

| Mason 2018b67 | Low risk | Some concerns | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns | Some concerns |

| McTavish 201268 | High risk | High risk | High risk | Some concerns | High risk | High risk |

| Muench 201769 | Low risk | Some concerns | Some concerns | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns |

| Mussener 201670 | Low risk | Some concerns | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Pechmann 201771 | Some concerns | Some concerns | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns |

| Reback 201972 | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Low risk | Some concerns |

| Rodda 201873 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns | Low risk |

| Schlam 202074 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns | Low risk |

| Scott 202075 | Some concerns | Some concerns | Low risk | Some concerns | Low risk | Some concerns |

| So 202076 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns | Low risk |

| Sridharan 201977 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns | Low risk | Low risk |

| Vilardaga 202078 | Some concerns | Some concerns | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns |

| Webb 202079 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Whittaker 201180 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Witkiewitz 201481 | Some concerns | Some concerns | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns |

| Xu 202182 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Ybarra 201383 | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

Table 2: Summary of ROB-2 quality assessment for included RCTs.

| Authors, Year | Criteria | Overall bias | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confounding | Selection of participants into the study | Classification of interventions | Deviations from intended interventions | Missing data | Measurement of outcomes | Selection of the reported result | ||

| Chen 201984 | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Eiler 202085 | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Rajani 202186 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Vilaplana 201487 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Serious | Moderate |

| Gonzalez and Dulin 201588 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Low |

Table 3: Summary of ROBIN-S quality assessment for included non-RCTs.

Data synthesis

We summarised study information and conducted a narrative review and qualitative literature synthesis to summarize the findings across studies. We used descriptive statistics to summarize the study and participant characteristics where appropriate.

The following outcomes were evaluated where possible:

· Types of recruitment strategies used

· Effectiveness of different recruitment strategies

· Population groups targeted

· Effectiveness of recruitment strategies for different

population groups and different disorders

· Explanation for differential recruitment

We also compared different recruitment methods on recruitment and retention numbers and how effective strategies were with different population groups.

Results

Study selection

The electronic search results in 2135 papers. After duplicates were removed, 1654 papers were screened for eligibility. After initial screening by title and abstract, 1550 papers were excluded, and 104 were included, including eight additional results papers identified from protocol papers meeting criteria. After full-text screening, there were 60 relevant papers (Figure 1). Of these papers, 53 were primary analyses, five secondary analyses and two protocols (Table 4). Study designs for the primary analyses included 45 randomized controlled trials; one pseudo-randomized trial, five non-randomized trials, and one cluster randomized controlled trial.

| Authors, Year | Study Design | Country | Topic | Population | Intervention | Recruitment | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size^ | Methods^ | |||||||

| Target | Actual | |||||||

| Abroms et al., 2014 [38] | RCT | US | Smoking | Adult Smokers (18+ y/o) | Text messaging program (Text2Quit) | -- | -- | No Information (--) |

| Abroms et al., 2017 [39] | RCT | US | Smoking | Pregnant women | Text messaging program (Text2Quit) | -- | -- | -- |

| Affret et al., 2020 [40] |

RCT | France | Smoking | Adult Smokers | Web & Mobile application (e-Tabac Info Service (e-TIS)) |

-- | -- | -- |

| Agyapong et al., 2012 [25] | RCT | Ireland | Alcohol | Adults with Major Depressive Disorder and Alcohol Dependency | Text message program | -- | -- | -- |

| Agyapong et al., 2018 [41] | RCT | Canada | Alcohol | Adults with Alcohol Use Disorder, final week of addiction treatment program |

Text message program | 60 | 59 | In-person (Addiction treatment program at Rehabilitation Centre) |

| Aigner et al., 2017 [42] | RCT | US | Smoking | Smokers with HIV+ status | Cell-phone-based counselling sessions | -- | -- | -- |

| Asayut et al., 2022 [89] | RCT | Thailand | Smoking | Thai Smokers | The “PharmQuit” app | -- | -- | In-person (invitation by pharmacy students, community pharmacists, health care providers, and health care volunteers) |

| Bindhim et al., 2018 [12] | RCT | US Australia SingaporeUK | Smoking | Adult Smokers (18+ y/o) | Mobile application (Smartphone Smoking Cessation App (SSC APP)) | -- | -- | -- |

Table 4: Overview of included studies, characteristics and recruitment

| Authors, Year | Study Design | Country | Topic | Population | Intervention | Recruitment | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size^ | Methods^ | |||||||

| Target | Actual | |||||||

| Bricker et al., 2014 [43] | RCT | US | Smoking | Adult Smokers (18+ y/o) | Mobile application(SmartQuit) | 196 | 196 | Online (Facebook advertisements, website advertisements, and search engine ads) Traditional (television, newspaper and radio advertisements) |

| Bricker et al., 2020 [44] | RCT | US | Smoking | Adult Smokers (18+ y/o) | Mobile application (iCanQuit) | 2500 | 2503 | Online (Facebook advertisements, survey sampling company, search engine advertisements) |

| Cambon et al., 2017 [85]* | RCT- Protocol |

France | Smoking | Adult Smokers (18+ y/o) | Web & Mobile application (e-Tabac Info Service (e-TIS)) |

3000 | NA | Online (advertisement onFrench Mandatory National Health Insurance website) |

| Chen et al.,2019 [81] | RCT | China | Alcohol | Adults 20-50 y/o, diagnosed with Alcohol Dependence | CBT on the WeChat platform | -- | -- | -- |

| Chen et al.,2020 [45] | Non-RCT | China | Smoking | Adult Smokers (25-44 y/o) | CBT on the WeChat platform (Smoking Cessation Intervention (SCAMPI)) | -- | -- | -- |

| Cheung et al., 2015 [46] | Cluster-RCT | China | Smoking | Adult Smokers (18+ y/o) | WhatsApp or Facebook online social group |

-- | -- | -- |

| Demartini etal., 2018 [47] | RCT | US | Alcohol | Recent drinking episode in past year (1+) | Text messaging program | -- | -- | -- |

| Destasio et al., 2018 [48] | RCT | US | Smoking | General Public not diagnosed with substance use, psychiatric or neurological disorder | Text messaging program | -- | -- | -- |

| Authors, Year | Study Design | Country | Topic | Population | Intervention | Recruitment | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size^ | Methods^ | |||||||

| Target | Actual | |||||||

| Eiler et al.,2020 [82] | Non-RCT | Germany | Smoking | Smokers | Mobile application (Approach- Avoidance Task (app-AAT)) | -- | -- | -- |

| Farren et al., 2022 [90] |

RCT | Ireland | Alcohol | Adults 18-70 with Alcohol UseDisorder as the primary disorder, who were inpatients completing therapeutic programmes. | Mobile application "UControlDrink”. The app incorporates daily supportive text messaging and C-CBT | -- | -- | Participants were recruited in-person from St. Patrick’s University Hospital, Dublin. |

| Forinash et al., 2018 [49] |

RCT | US | Smoking | Pregnant women | Text messaging program | 60 | 49 | In-person (MaternalFetal Care Center) |

| Garcia-Pazo etal., 2021 [91] | Pseudo- Randomized Clinical Trial | Spain | Smoking | Smokers admitted to a public hospital in the Migjorn health sector in the Balearic Islands. | Mobile application“NoFumo+”. | -- | -- | In-person. Interest was gauged at admission to hospital and recruitment was completed within 48 hours of first contact. |

| Glass et al., 2017 [86] | RCT- Secondary Analysis |

US | Alcohol | Adults diagnosed with Alcohol Dependency (18+) | Mobile application (Addiction- Comprehensive Health Enhance Support System (A- CHESS)) | -- | -- | -- |

| Goldenhersch et al., 2020 [50] | RCT | Argentina | Smoking | Adult Smokers (24-65 y/o) | Mobile application | -- | -- | -- |

| Gonzalez & Dulin, 2015 [84] | Non- randomized controlled trial | US | Alcohol | Adults diagnosed with Alcohol Use Disorder (18-45 y/o) | Mobile application (Location- Based Monitoring and Intervention for Alcohol Use Disorders (LBMI-A)) | -- | -- | -- |

| Graham et al., 2020 [51] | RCT | US | Smoking | Adult Smokers (18+) | Web program (EX) and Text message program | -- | -- | -- |

| Graham2021 [52] | RCT | US | Vaping | Adolescents e-cigarette users (18-24 y/o) | Text messaging program (Thisis Quitting (TIQ)) | 2600 | 2588 | Online (advertisementson Facebook and Twitter) |

| Authors, Year | Study Design | Country | Topic | Population | Intervention | Recruitment | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size^ | Methods^ | |||||||

| Target | Actual | |||||||

| Gustafson et al., 2014 [53] | RCT | US | Alcohol | Adults (18+ y/o) | Mobile application (Addiction- Comprehensive Health Enhance Support System (A-CHESS)) |

350 | 349 | In-person (Residential treatment programs) |

| Han et al., 2018 [87] | RCT- Secondary analysis |

China | Substance Use | Adults diagnosed with heroin dependence or amphetamine- type stimulants (ATS) dependence | Mobile application (S-Health) | -- | -- | -- |

| Haug et al., 2017 [54] | Cluster-RCT | Switzerland | Smoking & Alcohol | Smokers | Web and text messaging program | -- | -- | -- |

| Hébert et al., 2020 [55] | RCT | US | Smoking | Adult Smokers (18+ y/o) | Mobile application (Smart-T2) | -- | -- | -- |

| Hicks et al., 2017 [56] | RCT | US | Smoking | Adult Smokers with diagnosed PTSD (18-70 y/o) | Mobile contingency management smoking cessation counselling and medication as and Mobile application (Stay Quit Coach) | -- | -- | -- |

| Hides et al., 2018 [57] | RCT | Australia | Alcohol | Adolescents with monthly alcohol use (16-25 y/o) | Mobile application (Ray’sNight Out) | -- | -- | -- |

| Hoeppner etal., 2017 [58] | RCT | US | Smoking | Adult Smokers (18+ y/o) | Text messaging program (Text2Quit) | -- | -- | -- |

| Keoleian et al., 2013 [88] | RCT | US | Substance Use | Methamphetamine users seeking treatment | Text messaging program | -- | -- | -- |

| Liang et al., 2018 [60] | RCT | China | Substance Use | Adults, used heroin or other substance use in past 30 days | Mobile application (S-Health) | -- | -- | -- |

| Lucht et al., 2021 [61] | RCT | Germany | Alcohol | Adults diagnosed with alcoholdependence, ongoing inpatient alcohol detoxification (18+ y/o) | Text messaging program (Continuity of care among alcohol-dependent patients (CAPS)) | 462 | 463 | In-person (Psychiatric hospitals) |

| Authors, Year | Study Design | Country | Topic | Population | Intervention | Recruitment | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size^ | Methods^ | |||||||

| Target | Actual | |||||||

| Luk et al., 2019* [89] | Cluster-RCT- Protocol | China | Smoking | Adults Smokers | WhatsApp chat-based support | 1172 | NA | NA |

| Masaki et al., 2020 [62] | RCT | Japan | Smoking | Adults diagnosed with nicotine dependence | Mobile application (Cure App Smoking Cessation (CASC)) | 580 | 584 | In-person (Smoking cessation clinics) |

| Mason et al., 2014 [63] | RCT | US | Alcohol | Individuals diagnosed with problem drinking | Text messaging program (TROPO) | -- | -- | -- |

| Mason et al., 2018a [90] | RCT- Secondary analysis |

US | Substance Use | Adolescents diagnosed with cannabis use disorder (18-25 y/o) | Text messaging program (Peer Network Counseling (PNC-txt)) | -- | -- | -- |

| Mason et al., 2018b [64] | RCT | US | Substance Use | Adolescents diagnosed with cannabis use disorder (18-25 y/o) | Text messaging program (Peer Network Counseling (PNC-txt)) | -- | -- | -- |

| Mason 2020 [91] |

RCT- Secondary analysis |

US | Substance Use | Adolescents diagnosed with cannabis use disorder (18-25 y/o) | Text messaging program (Peer Network Counseling (PNC-txt)) | -- | -- | -- |

| Mctavish et al., 2012 [65] | RCT | US | Alcohol | Adults (18+ y/o) | Mobile application (Addiction- Comprehensive Health Enhance Support System (A- CHESS)) | -- | -- | -- |

| Muench et al.,2017 [66] | RCT | US | Alcohol | Adults consuming 13-15 standard drinks/week (21-65 y/o) |

Text messaging program | -- | -- | -- |

| Mussener et al., 2016 [67] | RCT | Sweden | Smoking | Smokers | Text messaging program (Nicotine Exit (NEXit)) | 1354 | 1590 | In-person (Student health care centres) |

| Pechmann etal., 2017 [68] |

RCT | US | Smoking | Adult Smokers (15-59 y/o) | Twitter peer support group | 160 | 160 | Online (Google advertisements using keywords fo quitting and support) |

| Authors, Year | Study Design | Country | Topic | Population | Intervention | Recruitment | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size^ | Methods^ | |||||||

| Target | Actual | |||||||

| Rajani et al., 2021 [83] | Non-RCT | UK | Smoking | Adult Smokers (18+ y/o) | Mobile application (Quit Genius) | 140 | 116 | Online (social media) Traditional (posters displayed across public places in London) |

| Reback et al., 2019 [69] | RCT | US | Substance Use | Adults with methamphetamine use andreported condomless anal intercourse | Text messaging program | -- | -- | -- |

| Rodda et al., 2018 [73] | RCT | Australia | Gambling | Individuals engaged with 1+ service by Gambling help online | Text messaging program | -- | -- | -- |

| Schlam & Baker, 2020 [71] |

RCT | US | Smoking | Individuals with e-cigarette use | Mobile game applications (arcade, puzzle, word, board, card, tower defense and running games) | -- | -- | -- |

| Scott et al., 2020 [72] | RCT | US | Substance Use | Individuals diagnosed with substance use disorder) | Mobile application (Addiction- Comprehensive Health Enhance Support System (A- CHESS)) | -- | -- | -- |

| So et al., 2020 73 | RCT | Japan | Gambling | Adults with Problem Gambling | Text messaging program (GAMBOT) | 198 | 197 | Online (Search engine advertisements for users searching for helpful information to stop gambling) |

| Sridharan et al., 2019 [74] | RCT | US | Smoking | Adults Smokers (18+) | Mobile application (SmartQuit) and web- de;overed growth mindsetintervention | 300 | 398 | Online (Facebook advertisements and internet survey panel) |

| Authors, Year | Study Design | Country | Topic | Population | Intervention | Recruitment | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size^ | Methods^ | |||||||

| Target | Actual | |||||||

| Tamí-maury et al. 2013 [92] | RCT- Secondary Analyses |

US | Smoking | Adult Smokers with HIV+ status (18+ y/o) | Cell-phone-based counseling sessions | -- | -- | -- |

| Vilaplana etal., 2014 [37] | Non- randomized controlled trial | Spain | Smoking | Patients at Smoking Cessation Program of Santa Maria Hospital | Web-based application (Smoker Patient Control (S- PC)) | -- | -- | -- |

| Vilardaga 2020 [75] | RCT | US | Smoking | Adult Smokers diagnosed witheither Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective, Bipolar, or recurrent major depressive disorder (18+ y/o) | Mobile applications (Learn to Quit & QuitGuide) | 90 | 92 | In-person (coordinating with primary care clinics,collaboration with smoking cessation programs and mental health clinics) Online (electronic healthrecords, patient health portal invitations) |

| Webb et al., 2020 [76] | RCT | UK | Smoking | Adult Smokers (18+ y/o) | Mobile application (Quit Genius) | 388 | 556 | In-person (Primary care practices) |

| Whittaker et al., 2011 [77] | RCT | NZ | Smoking | Young Māori Smokers (16+ y/o) |

Video-based text messagingprogram | 1300 | 226 | Online (Online magazine, Internet and mobile phone advertisements) Traditional (Advertisements to radio, paper-based magazines, Māori-specific media, local and national newspapers, and media releases) |

| Authors, Year | Study Design | Country | Topic | Population | Intervention | Recruitment | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size^ | Methods^ | |||||||

| Target | Actual | |||||||

| Witkiewitz et al., 2014 [78] | RCT | US | Smoking & Alcohol | College students with concurrent smoking and drinking and/or recent heavy drinking episode(s) | Mobile application (Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students (BASICS)) | -- | -- | -- |

| Xu et al., 2021 79 | RCT | China | Substance Use | Adults diagnosed with substance use disorder (20- 50y/o) | Web and Mobile application (Community-based addictionrehabilitation electronic system (CAREs)) and community-based rehabilitation | -- | -- | -- |

| Ybarra et al., 2013 [80] | RCT | US | Smoking | Adolescent Smokers (18-25 y/o) | Text messaging program (Text Care) and Text peer support program (Text Buddy) | -- | -- | -- |

| *Study Protocol RCT=Randomised Control Trial ^Blanks are for papers that did not report their sample size numbers and/or method. Target number of randomized participants according to either the power calculations or stated intentions of the study authors. Actual number of randomized participants included in the study. NA=Not Available | ||||||||

Study characteristics

The included studies primarily comprised primary analyses (N=53) [15,28,41-91], secondary analyses (N=5), [92-96] and study protocols (N=2) [97,98] The primary analyses were mostly RTCs (N=45) [15,28 ,41-47,50-56,58 -84], [89,90] pseudo-RCTs (N=1), [91] cluster RCTs (N=2) [49,97] and non-RCTs (N=5) [ 48,85-88] Secondary analyses were all based on RCTs, and the study protocols were based on an RCT and cluster RCT design each.

Most of the included studies were concerned with smoking cessation (N=33) [15,41-43], [45-49], [51-54], [58,59], [61,65,70,71,74 ,77-80,83,85-87,89,91,92,97,98] of which 30 were primary analyses, one secondary analysis, and two study protocols. Nine studies were concerned with problematic substance use (i.e., heroin, cannabis) [62,63, 67, 72, 75, 82, 93-95] of which six were primary analyses and three secondary analyses. Twelve studies were concerned with alcohol use [28, 44, 50, 56, 60] [64, 66, 68, 69, 84, 88, 96] of which 11 were primary analyses and one a secondary analysis. Two studies were concerned with co-occurring alcohol use and smoking, [57,81] all of which were primary analyses. Two primary analyses were found of interventions for problem gambling.73 75 one study was concerned with vaping cessation [55] as the primary analysis.

More than half of the included studies were from the United States (US) (n=32) [41,42,45-47,50-52 ,54-56,58,59,61,62,66- 69,71,72,74,75,77,78,81,83,88,92-94,96] Twelve studies were from Europe (including two from the United Kingdom (UK)) [28,43,57,64,70,79,85-87,98] ten from Asia [48,49,63,65]. [76,82,84,95,97 89] and one from South America [53 ] Two studies were from Australia [60,73] one from New Zealand (NZ) [80 ] and one from Canada.[44] The remaining study was a multi-site study that included participants from the USA, Australia, Singapore, and the UK [44] The most common mHealth intervention was text message programs (n=20) [28,41,42,44,50-52,55,61,62 ,64,66,67,69,70,72,73,76,93,94] and mobile applications (n=25) [15,46,47,53,56,58-60,63,65,68,74,75,77- 79,81,85,86,88,95,96 89-91 ] followed by social media groups (Facebook, Twitter, Whatsapp, and WeChat) (n=5) [48,49,71,84,97] web and mobile applications (n=3) [43,82,98] web and text messaging program (n=2) [54,57] video-based text message program (n=1) [80], text message and text peer support program (n=-1) [83] web application (n=1)87 and cell-phone based counseling sessions (n=2) [45,92] The number of participants ranged from 5 to 2806. Twenty-one studies had less than 100 participants, twelve were 100-199 participants, and fourteen had 200-499 participants. Eleven studies had more than 500 participants, of which six had more than 1000 participants (Table 4).

Risk of bias

The quality and risk of bias assessment for the RCTs showed that the majority of papers were deemed as ‘low risk’ or ‘some concerns’ for overall bias. The main areas of concern were limited information on the selection of the reported result and potential deviations for intended interventions. The few RCTs deemed ‘high risk’ were mainly for providing little information on the selection of the reported result, randomization process, or concealment process.

For the non-RCTs, the quality and risk of bias assessment revealed the papers as ‘low’ for overall bias except for Vilaplana [42] deemed as ‘moderate’. Within each criteria domain, each criterion was mainly deemed as ‘low’ for the papers except for the missing data, measurement of outcomes, confounding, and deviations from intended intervention domains

References

- Volberg RA, Williams R (2012) Developing a Short Form of the PGSI: Report to the Gambling Commission. Birmingham, England.

- World Health Organisation (2018). Global status report on alcohol and health. Report no. 978-92-4-156563- 9 World Health Organisation.

- Degenhardt L, Charlson F, Ferrari A (2018) The global burden of disease attributable to alcohol and drug use in 195 countries and territories 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. The Lancet Psychiatry 5: 987-1012.

- Peacock A, Leung J, Larney S (2018) Global statistics on alcohol, tobacco and illicit drug use: 2017 status report. Addiction (Abingdon, England) 113: 1905-1926.

- Ministry of Health. Preventing and Minimising Gambling Harm: Practitioner’s Guide. 2019. Wellington: Ministry of Health.

- Galea-Singer S, Newcombe D, Farnsworth-Grodd V (2020) Challenges of virtual talking therapies for substance misuse in New Zealand during the COVID-19 pandemic: an opinion piece. The New Zealand Med J 133: 104.

- Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Sampson NA (2011) Barriers to mental health treatment: results from the NationalComorbidity Survey Replication. Psychol Med 41: 1751-1761.

- Pullen E and Oser C (2014) Barriers to substance abuse treatment in rural and urban communities: counselor perspectives. Substance use & misuse 49: 891-901.

- Rizzo D, Mu T, Cotroneo S (2022) Barriers to Accessing Addiction Treatment for Women at Risk of Homelessness. Frontiers in Global Women’s Health 3.

- Rockville MD (2021) Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality cR MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Racial/ethnic differences in substance use, substance use disorders, and substance use treatment utilization among people aged 12 or older (2015-2019) Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

- Suurvali H, Cordingley J, Hodgins DC (2009) Barriers to Seeking Help for Gambling Problems: A Review of the Empirical Literature. J Gambl Stud 25: 407-424.

- Cumming C, Troeung L, Young JT (2016) Barriers to accessing methamphetamine treatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug and Alcohol Depend 168: 263-273.

- Schweitzer J, Synowiec C (2012) the Economics of Health and Health. J Health Commun17: 73-81.

- Cameron JD, Ramaprasad A, Syn T (2017) ontology of and roadmap for mHealth research. Int J Med Inform; 100: 16-25.

- Bindhim NF, McGeehan K, Trevena L (2018) Smartphone Smoking Cessation Application (SSC App) trial: a multicounty double-blind automated randomized controlled trial of a smoking cessation decision-aid ‘app’ 8: e017105.

- Pfaeffli L, Maddison R, Whittaker R (2012) A mHealth cardiac rehabilitation exercise intervention: findings from content development studies. BMC cardio dis 12: 36.

- Gimbel R, Shi L, Williams JE (2017) Enhancing mHealth Technology in the Patient-Centered Medical Home Environment to Activate Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Multisite Feasibility Study Protocol. JMIR Res Proto 6: e38.

- Muessig KE, Nekkanti M, Bauermeister J (2015) A Systematic Review of Recent Smartphone, Internet and Web 2.0 Interventions to Address the HIV Continuum of Care. Current HIV/AIDS Rep 12: 173- 190.

- Volkova E, Li N, Dunford E (2016) Smart RCTs: Development of a Smartphone App for Fully Automated Nutrition-Labeling Intervention Trials. JMIR mHealth uHealth 4: e23.

- Manji H, Saxena S (2019).The power of digital tools to transform mental healthcare.

- Warren I, Meads A, Whittaker R (2018) Behavior Change for Youth Drivers: Design and Development of a Smartphone-Based App. JMIR Formativ Res2: e25.

- Payne HE, Lister C, West JH (2015) Behavioral functionality of mobile apps in health interventions: a systematic review of the literature. J Med Internet Res3.

- Martínez PB, Torre-Díez I, López CM (2013) Mobile health applications for the most prevalent conditions by the world health organization: Review and analysis. JMIR 15.

- Tofighi B, Chemi C, Ruiz VJ (2019) Smartphone Apps Targeting Alcohol and Illicit Substance Use: Systematic Search in in Commercial App Stores and Critical Content Analysis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth7: e11831.

- Cohn AM, Hunter-Reel D, Hagman BT (2011) Promoting Behavior Change from Alcohol Use Through Mobile Technology: The Future of Ecological Momentary Assessment. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 35: 2209-2215.

- Gustafson DH, McTavish FM, Chih M-Y (2014) a Smartphone Application to Support Recovery from Alcoholism: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry 71: 566-572.

- Gajecki M, Berman AH, Sinadinovic K (2014) Mobile phone brief intervention applications for risky alcohol use among university students: a randomized controlled study. Addict Sci Clin Pract 9: 11.

- Agyapong VIO, Ahern S, McLoughlin DM (2012) Supportive text messaging for depression and comorbid alcohol use disorder: single-blind randomized trial. J Affect Disord 141: 168-176.

- Haug S, Schaub MP, Venzin V (2013) A pre-post study on the appropriateness and effectiveness of a Web- and text messaging-based intervention to reduce problem drinking in emerging adults. J Med Internet Res 15: 196.

- Suffoletto B, Callaway C, Kristan J (2012) Text-Message-Based Drinking Assessments and Brief Interventions for Young Adults Discharged from the Emergency Department. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 36: 552-560.

- Lucht MJ, Hoffman L, Haug S (2014) A Surveillance Tool Using Mobile Phone Short Message Service to Reduce Alcohol Consumption Among Alcohol-Dependent Patients. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 38: 1728-1736.

- Shrier LA, Rhoads A, Burke P (2014) Real-time, contextual intervention using mobile technology to reduce marijuana use among youth: A pilot study. Addict Behav 39: 173-180.

- Apollonio D, Philipps R, Bero L (2016) Interventions for tobacco use cessation in people in treatment for or recovery from substance use disorders. CDSR.

- Van der Meer RM, Willemsen MC, Smit F, (2013) Smoking cessation interventions for smokers with current or past depression. CDSR.

- Gilmore-Bykovskyi AL, Jin Y, Gleason C (2019) Recruitment and retention of underrepresented populations in Alzheimer’s disease research: A systematic review. TRCI 5: 751-770.

- Heller C, Balls-Berry JE, Nery JD (2014) Strategies addressing barriers to clinical trial enrollment of underrepresented populations: A systematic review. Contemp Clin Trials 39: 169-182.

- Silver L (2019) Smartphone Ownership Is Growing Rapidly Around the World, but Not Always Equally. Pew Research Center.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372: 71.

- Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE (2008) GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 336: 924.

- Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC (2016) ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomized studies of interventions. BMJ 355.

- Abroms LC, Boal AL, Simmens SJ (2014) A randomized trial of Text2Quit: A text messaging program for smoking cessation. Am J Prev Med 47: 242-250.

- Abroms LC, Johnson PR, Leavitt LE (2017) A Randomized Trial of Text Messaging for Smoking Cessation in Pregnant Women. Am J Prev Med 53: 781-790.

- Affret A, Luc A, Baumann C, (2020) Effectiveness of the e-Tabac Info Service application for smoking cessation: A pragmatic randomized controlled trial. BMJ Open 10.

- Agyapong VIO, Juhás M, Mrklas K, (2018) Randomized controlled pilot trial of supportive text messaging for alcohol use disorder patients. J Subst Abuse Treat 94: 74-80.

- Aigner CJ, Gritz ER, Tamí-Maury I (2017) the role of pain in quitting among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–positive smokers enrolled in a smoking cessation trial. Substance Abuse 38: 249-252.

- Bricker JB, Mull KE, Kientz JA (2014) Randomized, controlled pilot trial of a smartphone app for smoking cessation using acceptance and commitment therapy. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 143: 87-94.

- Bricker JB, Watson NL, Mull KE (2020) Efficacy of Smartphone Applications for Smoking Cessation: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med 180: 1472-1480.

- Chen J, Ho E, Jiang Y (2020) Mobile social network-based smoking cessation intervention for Chinese male smokers: Pilot randomized controlled trial. JMIR mHealth uHealth 8.

- Derek Cheung YT, Helen Chan CH, Lai CKJ (2015) Using Whatsapp and Facebook online social groups for smoking relapse prevention for recent quitters: A pilot pragmatic cluster randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 17.

- DeMartini KS, Schilsky ML, Palmer A, (2018) Text Messaging to Reduce Alcohol Relapse in Prelisting Liver Transplant Candidates: A Pilot Feasibility Study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 42: 761-769.

- DeStasio KL, Hill AP and Berkman ET (2018) Efficacy of an SMS-Based Smoking Intervention Using Message Self- Authorship: A Pilot Study. J Smok Cessat 13: 55-58.

- Forinash AB, Yancey A, Chamness D, (2018) Smoking Cessation Following Text Message Intervention in Pregnant Women. Ann Pharmacother 52: 1109-1116.

- Goldenhersch E, Thrul J, Ungaretti J (2020) Virtual reality smartphone-based intervention for smoking cessation: Pilot randomized controlled trial on initial clinical efficacy and adherence. J Medical Internet Res 22.

- Graham AL, Papandonatos GD, Jacobs MA (2020) Optimizing Text Messages to Promote Engagement With Internet Smoking Cessation Treatment: Results From a Factorial Screening Experiment. J Med Internet Res 22: e17734.

- Graham AL, Amato MS, Cha S (2021) Effectiveness of a Vaping Cessation Text Message Program among Young Adult e-Cigarette Users: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med 181: 923-930.

- Gustafson DH, McTavish FM, Chih MY (2014) A smartphone application to support recovery from alcoholism a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 71: 566-572.

- Haug S, Paz Castro R, Kowatsch T (2017) Efficacy of a technology-based, integrated smoking cessation and alcohol intervention for smoking cessation in adolescents: Results of a cluster-randomized controlled trial. J Subst Abuse Treat 82: 55-66.

- Hébert ET, Ra CK, Alexander AC (2020) a mobile just-in-time adaptive intervention for smoking cessation: Pilot randomized controlled trial. J. Medical Internet Res 22.

- Hicks TA, Thomas SP, Wilson SM (2017) A Preliminary Investigation of a Relapse Prevention Mobile Application to Maintain Smoking Abstinence Among Individuals With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. J Dual Diagn 13: 15-20.

- Hides L, Quinn C, Cockshaw W (2018) Efficacy and outcomes of a mobile app targeting alcohol use in young people. Addictive Behaviors 77: 89-95.

- Hoeppner BB, Hoeppner SS, Abroms LC (2017) how do text-messaging smoking cessation interventions confer benefit? A multiple mediation analysis of Text2 Quit. Addiction; 112: 673-682.

- Keoleian V, Alex Stalcup S, Polcin DL A (2013) Cognitive Behavioral Therapy-Based Text Messaging Intervention for Methamphetamine Dependence. J Psych Drugs 45: 434-442.

- Liang D, Han H, Du J (2018) a pilot studies of a smartphone application supporting recovery from drug addiction. J Sub Abu Treat 88: 51-58.

- Lucht M, Quellmalz A, Mende M (2021) Effect of a 1-year short message service in detoxified alcohol-dependent patients: a multi-center, open-label randomized controlled trial. Addiction 116: 1431-1442.

- Masaki K, Tateno H, Nomura A (2020) A randomized controlled trial of a smoking cessation smartphone application with a carbon monoxide checkers. npj Digital Med 3.

- Mason M, Benotsch EG, Way T (2014) Text messaging to increase readiness to change alcohol use in college students. J Primary Prev 35: 47-52.

- Mason MJ, Zaharakis NM, Moore M (2018) who responds best to text-delivered cannabis use disorder treatment? A randomized clinical trial with young adults. Psychology of addictive behaviors: J Soc Psych Add Beh 32: 699-709.

- McTavish FM, Chih MY, Shah D (2012) How patients recovering from alcoholism use a smartphone intervention. J Dual Diag 8: 294-304.

- Muench F, Van Stolk-Cooke K, Kuerbis A (2017) A randomized controlled pilot trial of different mobile messaging interventions for problem drinking compared to weekly drink tracking 12.

- Müssener U, Bendtsen M, Karlsson N (2015) Effectiveness of short message service text-based smoking cessation intervention among university students a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Int Med 176: 321-328.

- Pechmann C, Delucchi K, Lakon CM (2017) Randomized controlled trial evaluation of tweet2quit: A social network quit-smoking intervention. Tobacco Control 26: 188-194.

- Reback CJ, Fletcher JB, Swendeman DA (2019) Theory-Based Text-Messaging to Reduce Methamphetamine Use and HIV Sexual Risk Behaviors among Men Who Have Sex with Men: Automated Unidirectional Delivery Outperforms Bidirectional Peer Interactive Delivery. AIDS and Behavior; 23: 37-47.

- Rodda SN, Dowling NA, Knaebe B (2018) Does SMS improve gambling outcomes over and above access to other e-mental health supports? A feasibility study. Int Gambl Stud; 18: 343-357. Article.

- Schlam TR, Baker TB (2020) Playing Around with Quitting Smoking: A Randomized Pilot Trial of Mobile Games as a Craving Response Strategy. Games Health J 9: 64-70.

- Scott CK, Dennis ML, Johnson KA (2020) A randomized clinical trial of smartphone self-managed recovery support services. J Substance Abuse Treat 117.

- So R, Furukawa TA, Matsushita S (2020) Unguided Chatbot-Delivered Cognitive Behavioural Intervention for Problem Gamblers Through Messaging App: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Gambling Stud 36: 1391-1407.

- Sridharan V, Shoda Y, Heffner J (2019) a pilot randomized controlled trial of a web-based growth mindset intervention to enhance the effectiveness of a smartphone app for smoking cessation. JMIR mHealth and uHealth 7.

- Vilardaga R, Rizo J, Palenski PE (2020) Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial of a Novel Smoking Cessation App Designed for Individuals With Co-Occurring Tobacco Use Disorder and Serious Mental Illness. Nicotine & tobacco research: official J Soc Res Nicotine and Tobacco 22: 1533-1542.

- Webb J, Peerbux S, Smittenaar P (2020) Preliminary outcomes of a digital therapeutic intervention for smoking cessation in adult smokers: Randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mental Health 7.

- Whittaker R, Dorey E, Bramley D (2011) a theory-based video messaging mobile phone intervention for smoking cessation: Randomized controlled trial. J Med Int Res13.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at , Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at , Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at , Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at , Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at , Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at , Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Citation: Kidd B, McCormack JC, Newcombe D, Garner K, O’Shea A, et al. (2023)Recruitment and Retention in mhealth Interventions for Addiction and ProblematicSubstance Use: A Systematic Review. J Addict Res Ther 14: 582.

Copyright: © 2023 Kidd B, et al. This is an open-access article distributed underthe terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricteduse, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author andsource are credited.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Usage

- Total views: 2579

- [From(publication date): 0-2023 - Dec 18, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 2218

- PDF downloads: 361