Reproductive and Productive Performance of Indigenous Cattle Breed in Bena-Tsemay District of SoutOmo, South-Western Ethiopia

Received: 09-Aug-2021 / Accepted Date: 16-Sep-2021 / Published Date: 24-Sep-2021 DOI: 10.4172/2332-2608.1000312

Abstract

The understanding the productive and reproductive potential of indigenous cattle is vital for designing an appropriate cattle breeding and management strategies. This study aims better understanding the reproductive and productive potential of indigenous cattle reared in the three cattle production system of Bena-Tsemay district of South Omo. The face-to-face household survey was conducted by interviewing 150 households of eight purposively selected Kebeles from the three cattle production systems. Age at First Services (AFS), Age at First Calving (AFC), Calving Interval (CI), Days Open (DO) and Number of Service Per Conception (NSPC) were consider as reproductive traits, while Daily Milk Yield (DMY) and Lactation Length (LL) were considered as productive traits. The collected data were analyzed by using One-Way ANOVA by using SPSS, version 20. In pastoral production system, the heifer early comes (P<0.001) at AFS and AFC than agro-pastoralist and crop-livestock production systems and however, it was non-significant (P>0.001) for later of two production systems. The result from this study also reveals that there was longer (P<0.001) numbers of DO were observed for cow reared in pastoral system than agro-pastoral and mixed crop-livestock production systems however, the shorter (P<0.001) CI was reported from pastoral production system than later of two production systems. The higher (P<0.001) average DMY and longer (P<0.001) LL were reported from crop-livestock and agro-pastoral production systems than pastoral production system. Based on the results from this study, it was concluded that the reproductive and productive performances of cattle in the study area were low and therefore, the collaborative efforts needs in the indigenous cattle breed genetic improvement, improvements in feeds and feeding systems and strengthening veterinary supply services.

Keywords: Agro-pastoral; Crop-livestock; Pastoral; Reproductive and productive traits

Introduction

Ethiopia has comprised of 60.39 million heads of cattle which consists of 98.24% indigenous, 1.45% hybrid and 0.22% exotic cattle breeds [1]. The cattle are consists of cow and oxen and have the capability to adapt various agro-ecological zones of Ethiopia and can produce milk, milk products and meat [2,3]. Similarly, in the Bena- Tsemay district, the cattle production are vital for the livelihoods small holder farmers, agro-pastoralists and pastoralists through generating cash income, source of food (milk, milk product and meat), fulfilling cultural obligations, source of organic fertilizers and animal traction [4-6]. However, with this fundamental contribution to rural communities, the traits such as age at first service, age at first calving, calving interval, number of services per conception and days open till conception are describes as reproductive traits of cattle while meat and milk, and lactation length are refers to productive traits [7-10]. The reduced availability communal grazing-land, lack of improved forage production and extensive feeding systems, poor animal health delivery system and low genetic make-up of local breeds are an important factor that challenged the cattle reproductive and productive traits in South Omo [6,11]. The understanding the productive and reproductive performance potential of cattle that have been rearing in the Bena- Tsemay district is vital for designing an appropriate cattle breeding and management strategies due to the cattle that are reared in the study district are local breeds and this recalls the any interventions in improving the productive and reproductive performance of local cattle through designing an appropriate breeding strategies after understanding their genetic potentials in their production niches. The study reported by [6] from Malle district of South Omo was demonstrated that means of age at first service was (58.75 months), calving interval (22.70 months), daily milk yield (1.40) liters and average lactation length (405.5) for midland and lowland agroecologies. Also, the study reported by [11] from the South Omo showed that the age at first breeding of male and female cattle were 3.6 and 3.4 years, respectively with average calving interval (14.5 months). However, there is no study has been conducted on reproductive and productive performances of local cattle have been rearing in the Bena- Tsemay district in order to fully utilize the existing cattle breeds in their breeding niches. Therefore, this study aimed at (1) to assess the effect of production systems on reproductive and productive performance of indigenouscattle breeds (2) to assess the effects of breeding seasons on productive performances of indigenous cattle breeds.

Materials and Methods

Description of study area

The study was conducted in Bena-Tseamy district of South Omo Zone. The Bena-Tseamy district has lied between 5001’ and 5073’ North latitude and 36038’ and 37007’ East longitude in the Southern Nations, Nationalities and People’s Region of Ethiopia. The district is characterized by semi-arid and arid climatic conditions, with mean annual rainfall averaging from 350-838 mm in bimodal distribution with the long rainy season from March to June while the small rains between September and October with an ambient temperature ranging from 26-35ºC [12]. The vegetation of the study area is dominated by varying densities of Acacia, Grewia, and Solanum woody species [4, 13]. The dominant type of land-use is agro-pastoralism [5,13] and more than 48% of the total land area of the district is used for grazing and browsing by cattle and goats, respectively [4]. Depending on the agroecologies, the agro-pastoralists in the study district are practicing rainfed agriculture and sorghum, maize, millet, bean, wheat, barley, and vegetables are the major crops grown in the study area [4]. The Bena ethnic group, who live in the higher altitude of Bena-Tsemay district are engaged more in crop production than the other pastoral groups because of the favorable climatic condition and whereas, the Tsemay pastoralists living in the lower altitude area of Bena-Tsemay district depend more on livestock production because of the unfavorable climatic condition for crop production[4]. The estimated human population of the Bena-Tsemay district was about 86, 691 of which 44,591 male and 42,100 are females [14] and whereas, the population of livestock are estimated to be 525,941 cattle, 211,818 sheep, 910, 252 goats, 235, 363 Poultry and 36, 387 donkeys [15] (Figure 1).

Study design

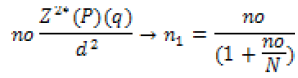

Sample selection procedure and sample size:A multistage sampling procedure was employed to select study Kebeles (lowest administrative sub-unit). The first stage involved was stratification of the 34 Kebeles of Bena-Tsemay district into three based on production systems (Pastoralists, Agro-pastoralists and mixed crop-livestock). In the second stage, purposive sampling techniques was employed to select the sample study Kebeles from each production system based on the cattle population and cattle rearing experience. The three Kebeles such as Sitemba, Luka and Anesonda from pastoral, four Kebeles namely Argo, Shaba, Gurdo and Sile from the agro-pastoral production system and Chali from mixed crop-livestock production system were purposely selected for face-to-face household interview. Lastly, a simple random sampling technique was employed to select households from each Kebeles that owned cattle. The sample size from each Kebele was determined based on proportion to the total human population in each selected Kebele and thus, a total of 150 households (57 households from pastoral, 55 households from agro-pastoral and 38 households from mixed crop-livestock production system) were selected. The [16] sampling technique was used to estimate total households.

Where, no= desired sample size according to Cochran’s (1977) when population greater than 10,000; n1 = finite population correction factors population less than10, 000; Z = standard normal deviation (1.96 for 95% confidence level); P = 0.11 (proportion of population to be included in sample i.e. 11%); q=1-0.11 i.e. (0.89); d = is degree of accuracy desired (0.05), 5% error term.

Data collection methods

Household survey:Primary data on cattle productive and reproductive performances were collected through interviewing the households using a semi-structured questionnaire prepared for this purpose. During the face-to-face interview, the information such as Age at First Service (AFS), Age at First Calving (AFC), Calving Interval (CI), Number of Services Per Conception (NSPC), Days Open Till Conception (DO), Average Daily Milk Yield(DMY) and average Lactation Length (LL) were collected from interviewed households.

Methods of data analysis:Data collected from the face-to-face interview were entered and managed using the MS excel computer program and the means of the reproductive and productive traits were analyzed using One-Way ANOVA and the significance among the means across production system and breeding seasons were compared by using Duncan’s multiple range test and values were considered significant at P<0.001 by using Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS, version20). The following models were used for analyzing the effect of livestock production systems and breeding seasons on reproductive and productive performance traits of cattle in Bena- Tsemay district.

Model 1: The statistical model for the analysis of the effect of livestock production systems on reproductive and productive traits;

Yijk = μ + PSi+ eijk; Where: Yij = reproductive and productive traits (AFS, AFC, CI, DO, NSPC, DMY and LL); μ = Overall population means; PSi = the effect of ith livestock production systems (i = Pastoral, Agro-pastoral and Mixed crop-livestock); eijk= Random error.

Model 2: The statistical model for the analysis of the effect of breeding seasons on productive performances of cattle; Yij= μ + Si + eij

Yij = Observation on productive performances (DMY and LL) of cattle; μ = Overall population mean; Si = effect of ith seasons (i = Wet and Dry).

Results and Discussion

Reproductive performances of cattle

The reproductive performances of cattle in the Bena-Tsemay district are presented in Table 1. There was non-significant (P>0.001) difference observed for age of bull and heifer at first service across the three production systems. The average ages of bull at first service in the study area was 25.3±2.31 for pastoral, 26.95±2.06 for agro-pastoral, and 25.47±2.37 for mixed crop-livestock production system. The result from the present study on age at first service of male was lower than reported values of (43.20 month) for Mursi cattle [11], (46.80 month) for Malle cattle [6], (36 months) for steers of GamoGofa cattle [17], (40.2 months) for Arsi steers [18] and (55.20 months) for Borana cattle [19]. The lower age at first service of bull in cattle in the study district as compared to other areas in the Ethiopia might be due to either Figure 1: Map of study area. breed differences [11] or poor nutrition [6,20]. In pastoral production system, the heifer early comes (P<0.001) at age first service and age at first calving as it was compared with heifers that were reared in agropastoralist and crop-livestock production system and however, there was non-significant differences (P>0.001) observed for heifers reared in later of two production systems. The reason for heifer early comes at first service and calving in pastoral system might be due fact that pastoral production system characterized by higher environmental temperature which might be initiate quickly age come at first heat. In supports to result from this study [21] reported that Dawiro cows that were reared in lowland agro-ecology comes early at first calving than cows reared in the midland and highland due to higher temperature which might be initiate quickly age at first heat. The puberty is influenced by breed difference, body weight, nutrition status, thermal stress and rearing methods. The age at first service of heifer in the present study was earlier than the value (42.52 months) reported by [22] for Ethiopian Boran heifers and cows and [23] for local Horro heifers (48.9 months). The age at fist calving for heifers in the study area was earlier than the value (55.20 months) reported for Mursi cow [11], (58.78 months) for Malle cow [6]. Day open is the interval between date of calving and date of conception and it is commonly used to measure fertility traits in cows and may affect the overall economic revenues from the cattle production systems [10]. The result from this study reveals that there was significantly longer (P<0.001) numbers of days open were observed for cows in pastoral system than agro-pastoral and mixed croplivestock production systems. The prolonged days open for pastoral production system is due to poor feeding system and prevalence of diseases and parasites loads according to respondents. The result from this study on the average days open for local cow in the study area was lower than reported value of (360days) by [24] for local cattle reared in Gurage area and (340days) reported by [25] for Boran cows that reared at Tatesa Cattle Breeding Center. The Calving Interval (CI) is the time between two successive parturitions and has a great economic importance on the life time milk production and productive life of cows, which ultimately affects the economics of the cattle owners. The result reveals that significantly shorter (P<0.001) calving interval was observed in pastoral production system than agro-pastoral and mixed crop-livestock production systems. The prolonged calving interval observed for agro-pastoral and mixed crop-livestock production than pastoral production might be due to better feed quality and feeding practices due high availability of crop residues in agro-pastoral and mixed crop-livestock production than pastoral production system. The calving interval of this study was within estimates of (12.20 to 26.60 months) for Zebu (Mursi) cattle reported by [11], (17.06 months) for Begait cow [26], (17.81 months) reported by [26] for Ethiopian Boran herd maintained at Abernossa ranch and but lower than (22.7 months) for Malle cattle by [6] and (21.24 months) for Bonga cow reported by [27]. The Number of Service Per Conception (NSPC) is shows that how many services are required for a successful conception of breeding cows and it is calculated by dividing the number of conceptions with the number of inseminations [28]. The result from this study reveals that the number of services per conception were not affected (P>0.05) among thee livestock production systems. The similarity in NSPCamong three livestock production systems from this study is due to similar in mating system (uncontrolled natural mating) used in the study area. The average NSPC of three production systems were higher than value (1.28) for Fogera cattle at Metekel Ranch [29]and (1.54) for local cows reared midland of Alefta district [10] but it was lower than value (1.82) for local cows reared in lowland from Quara district reported by same author.

| Cattle Production Systems | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reproductive Traits | Pastoral (N = 57) |

Agro-pastoral (N = 55) |

Crop-livestock (N = 38) |

Overall (N = 150) |

P-vale |

| ABFS (month ± SEM) | 25 ± 2.3 | 26.95 ± 2.1 | 25.47 ± 2.4 | 25.96 ± 1.9 | 0.84NS |

| AHFS (month ± SEM) | 38b ± 0.1 | 40.42a ± 0.2 | 40.31a ± 0.2 | 39.50 ± 0.1 | 0.001*** |

| AFC (month ± SEM) | 47b ± 0.2 | 49.58a ± 0.2 | 49.53a ± 0.20 | 48.69 ± 0.1 | 0.001*** |

| DO (days ± SEM) | 173a ± 0.1 | 168.89b ± 0.1 | 167b ± 0.21 | 170.01 ± 0.2 | 0.001*** |

| CI (month ± SEM) | 15.89b ± 0.1 | 18a ± 0.1 | 18a ± 0.18 | 17.34 ± 0.1 | 0.001*** |

| NSPC (days ± SEM) | 1.73 ± 0.07 | 1.72 ± 0.1 | 1.70 ± 0.1 | 1.72 ± 0.0 | 0.92NS |

| Means with different superscripts (a,b) within a row across cattle production system for reproductive performances are significantly different at P < 0.001; *** = highly significant differences at p < 0.001; N = Number of respondents; NS = Non-Significant difference; SEM = Standard Error of Mean; ABFM= Age of Bull at First Service; AHFS = Age of Heifer at First Service; AFC = Age at First Calving; DO = Days Open; CI = Calving Interval; NSPC= Number of Service Per Conception. | |||||

Table1: Reproductive performances of cattle (Mean ± SEM) reared in Bena-Tsemay.

Productive performances of cattle

The productive performances of local cows in the study district are presented in Table2. The Daily Milk Yield (DMY/cow) is a very important productive trait, which is a combination of milk yield and lactation length. Significantly higher (P<0.001) average daily milk yield was observed for crop-livestock and agro-pastoral production systems than pastoral production system in wet and dry seasons. According to respondents, the higher daily milk yield for agro-pastoral and mixed crop-livestock production systems are due to better feed availability and feeding systems. The respondents of agro-pastoral and mixed crop-livestock productions were reported that they have a trend of collecting and storing crop-residues and provision of feed supplements to their milking cows in addition to pasture grazing at communal grazing-land. Moreover, in mixed crop-livestock production system, respondents mentioned that they mainly supplement to their milking cows with locally available material like Atella (local Brewery byproduct) in the morning in addition to crop residues and grazing. The average daily milk yield obtained from the present study is lower than the value (1.46 litters) reported by [6] for Malle cows reared at midland agro-ecology and (1.9 liters) per days for local cows in Ethiopia [3]. Whereas, the average daily milk yield reported from the mixed crop livestockproduction system was higher than value (1.40 litters) reported by [6] for Malle cows and (1.37 litters) for local cows in Ethiopia[1]. However, the result from the present study generally is much lower than value of (2.9 liters/day) for Nuer cows reported by [30] and (2.2 litters) in highland and (2.3litters) in midland agroecologies for indigenous cows from Dawuro area [21]. Lactation length is one of factors that regulate profitability of a given cows. The significantly (P<0.001) longer lactation length was reported from agropastoral production system than pastoral production system but it was comparable (P>0.001) to mixed crop-livestock production systems in both wet and dry seasons. Therespondents of agro-pastoral and mixed crop-livestock production systems mentioned that longer lactation length for agro-pastoral and mixed crop-livestock production systems might be related with better rainfall distribution which results better range-land forage availability and hence, extend the lactation length.

| Productive performance | Production system | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pastoral (N = 57) |

Agro-pastoral (N = 55) |

Crop-livestock (N = 38) |

Overall (N = 150) |

P-Value | |

| DMY(Lt) in wet season (Mean + SEM) | 0.98b ± 0.02 | 1.21a ± 0.03 | 1.89a ± 0.05 | 1.22 ± 0.02 | 0.001*** |

| DMY (Lt) in dry season (Mean + SEM) | 0.65b ± 0.01 | 0.89a ± 0.01 | 0.92a ± 0.02 | 0.81 ± 0.01 | 0.001*** |

| LL (month) in wet season (Mean + SEM) | 5.88b ± 0.10 | 7.02a ± 0.11 | 6.89a ± 0.14 | 6.55 ± 0.08 | 0.001*** |

| LL (month) in dry season (Mean + SEM) | 2.70b ± 0.10 | 3.45a ± 0.06 | 3.55a ± 0.08 | 3.19 ± 0.05 | 0.001*** |

| (Means with different superscripts (a, b) within a row across the three cattle production system for productive performances are significantly different at P < 0.001; N = Number of Respondents; SEM = Standard Error of Mean; DMY = Daily Milk Yield; LL = Lactation Length. Lt = Liter) | |||||

Table 2: Productive performance of cattle (Mean ± SEM) reared in Bena-Tsemay district.

Similarly, [21] reported that the availability of feed and water and less impact of temperature extends the lactation length in cows. The result from the present study for lactation length is lower than reported value (8.24 months) by [6] for Malle cow, (7.8 months) by [11] for Mursi cow, (9.13 months) by [31] for local breed in North Showa Zone.

Effect of seasons on productive performance:The effects of seasons on productive performances of local cow in the study area are presented in Table 3. The higher (P<0.001) daily milk yield and lactation length were reported in wet seasons than dry seasons. According to respondents, the higher milk yield obtained in wet seasons from this study is due to sufficient rainfall amount in wet season as consequence a better quality and quantity of forages availability from the range-land in the study area. In agreement to the present study, [32] reported that dairy cows that calved in wet seasons gave greater milk yield than those calved in dry seasons due to better nutrient availability from rangeforage (3215 vs.2891kg). From this study it was observed that 0.32 litters (28.57%) of milk reduction and 1.55 months (27.34%) shorten in lactation length were observed as result ofdry season occurrences as compared to wet seasons. In agreement to result from this study also [33] and [34] reported that in the dry season the availability and quality of pasture reduced to such an extent that dairy cows may not fulfill the energy requirement to maintain their body weight and this has resulted in body weight loss and reduction of milk yield. However, the results from Italian [35], Turkish [36] and Pakistani [37] studies showed that the Holstein Friesian cows calved in wet (December to February) had similar milk yield per lactation as compared to cows calved in summary seasons which is contradicted to the result from the present study.

| Variables | Effect of seasons on productive performance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Wet Season (Means ± SE) |

Dry Season (Means ± SE) |

Over all (Means ± SE) |

P-value | |

| Daily milk yield (Liters) | 150 | 1.12A ± 0.03 | 0. 80B ± 0.02 | 0.96 ± 0.02 | 0.001*** |

| Lactation Length (month) | 150 | 5.67A ± 0.15 | 4.12B ± 0.13 | 4.89 ± 0.11 | 0.007*** |

| (Means with different superscripts (A, B) in a row for effect of season on productive performance are significantly difference at P < 0.001; N = Number of respondents; SEM = Standard Error of Mean) | |||||

Table 3: The effect of seasons on productive performance of cattle (Mean ± SEM) reared in Bena-Tsemay district.

Conclusions

In pastoral production system, the heifer early comes at AFS and AFC than agro-pastoralist and crop-livestock production systems. The result from this study also reveals that there was longer numbers of DO were observed for cow in pastoral system than agro-pastoralist and crop-livestock production systems. The higher average daily milk yield and longer lactation length were reported from crop-livestock and agro-pastoral production systems than pastoral production system. Based on the results from this study, it was that the reproductive and productive performances of cattle in the study area were low and therefore, the collaborative efforts needs in the indigenous cattle breed genetic improvement, improvements in feeds andfeeding systems and strengthening veterinary supply services.

Acknowledgments

Our special thanks and appreciation goes to Bena-Tsemay district Livestock and Fisher Resource Development Office (LFDO) and Trade and Market Development Office for providing us with all the relevant secondary information related to our study. We are also grateful to pastoralists, agro-pastoralists and farmers of Bena-Tsemay district who responded to all questions with patience and gave necessary information for our research work.

Conflict of Interests

We declared that there any no conflict of interests for this article and we read revised and approved this manuscript for publication.

References

- Central Statistical Agency (CSA) (2018) Agricultural Sample Survey, Report on livestock and livestock characteristics (Private peasant holdings), volume II, Statistical Bulletin, 587. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- Berhane H (2017) Ethiopian cattle genetic resource and unique characteristics under a rapidly changing production environment-A review. Int J Sci Res (IJSR) 6: 1959-1968.

- FAO (Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations) (2018). Africa sustainable livestock production systems spotlight Cattle sectors in Ethiopia. pp 1-11.

- Admasu T, Abule E, Tessema Z (2010) Livestock-rangeland management practices and community perceptions towards rangeland degradation in South Omo zone of Southern Ethiopia, Livestock Research for Rural Development 22.

- Berhanu T, Abebe G, Thingtham J, Tusdri S, et al. (2017) Availability of feed resources for goats in pastoral and agro-pastoral districts of south omo zone, Ethiopia. Int J Sci Res - Granthaalayah, 5: 154-160.

- Getaneh D, Banerjee S, Taye M (2019) Husbandry and Breeding Practices of Malle Cattle Reared in Malle District South Omo Zone of Southwest Ethiopia, J Anim Vet Adv 18: 323-338.

- Habtamu L, Kelay B, Desie S (2010) Study on the reproductive performance of Jersey cows at Wolaita Sodo dairy farm, Southern Ethiopia. Ethiopian Vet J 14: 53-70.

- Aynalem H, Workneh A, Noah K, Tadelle D, Azage T (2011) Breeding strategy to improve Ethiopian Boran cattle for meat and milk production. IPMS (Improving Productivity and Market Success) of Ethiopian Farmers Project Working Paper 26. Nairobi, Kenya, ILRI.

- Demissu H, Fekadu B, Gemeda D (2013) Early growth and reproductive performance of Horro cattle and their F1-Jersey crosses in and around Horro-Guduru livestock production and research center, Ethiopia. Sci Tech Art Res 3: 134-141.

- Ayeneshet B, Wondifraw Z, Abera M (2017) Survey on Farmers Husbandry Practice for Dairy Cows in Alefa and Quara Districts of North Gondar Zone, Amhara National Regional State, Ethiopia. Int J Anim Sci 1: 1010.

- Terefe E, Dessie T, Haile A, Mulatu W, Mwai O (2015) On-farm phenotypic characterization of Mursi cattle in its production environment in South Omo Zone, Southwest Ethiopia. Anim Genet Resource 57: 15-24.

- Mulugeta A, Getahun T (2002) Socio-economy of pastoral Community in Bena-Tsemay and Hammer Woredas of South Omo Zone, Southern Nations and Nationalities peoples Regional State. September 2002, Addis Abeba, Ethiopia.

- Hidosa D, Hailu S, O’Reagain J (2020) “Goat Feed Inventory and Feed Balance in Hamer and Bena-Tsemay Woreda of South Omo Zone, South Western Ethiopiaâ€. Acta Scientific Veterinary Sciences 2: 28-43.

- OFED (Office of Finance and Economic Development) (2019) Annual human population Statistical Report, Bena-Tsemay Woreda, South Omo Zone.

- LFRDO (Livestock and Fisher Resource Development Office) (2019) Annual livestock extension report, Bena-Tsemay Woreda, South Omo Zone.

- Cochran WG (1997) Sampling techniques (3rd Edn.) New York: John Wiley and Sons.

- Giorgis KH, Jimma A, Getiso A, Zeleke B (2017) Characterization of Gofa Cattle Population, Production System, Production and Reproduction Performance in Southern Ethiopia. J Fisheries Livest Prod 5: 3-7.

- Gudeto A (2018) Studies on structural, functional traits and traditional breeding Practices of Arsi cattle in East Showa and West Arsi Zone of Oromia Reginal State Ethiopia. M. Sc. Thesis, College of Agriculture, Hawassa University. Hawassa. 79p.

- Takele D (2014) Assessment of dairy cattle husbandry and breeding management practices of lowland and mid-highland agro-ecologies of Borana Zone. Anim Vet Sci 2: 62-69.

- Hidosa D, Tesfaye Y, Feleke A (2017) Assessment on Feed Resource, Feed Production Constraints and Opportunities in Salamago Woreda in South Omo Zone, in South Western Ethiopia. Acad J Nutr 6: 34-42.

- Hussein T (2018) Productive and Reproductive Performance of Indigenous Ethiopian Cow under Small Management in Dawro Zone, Southern Ethiopia. Int J Curr Res Acad Rev 6: 2347-3215.

- Kebamo M, Jergefa T, Dugassa J, Gizachew A, Berhanu, T (2019) Survival rate of calves and assessment reproductive performance of heifers and cows in Dida Tuyura Ranch, Borana Zone, Southern Ethiopia. Vet Med Open J 4: 1-8.

- Demissu H, Fekadu B, Gemeda D (2013) Early growth and reproductive performance of Horro cattle and their F1-Jersey crosses in and around Horro-Guduru livestock production and research center, Ethiopia. Sci Tech Art Res J 3: 134-141.

- Ayalew W, Feyisa T (2017). Productive and Reproductive Performance of local cows in Guraghe Zone, South West Ethiopia. J Anim Feed Res 7: 105-112.

- Yifat D, Bahilibi, Desie S (2012) Reproductive Performance of Boran Cows at Tatesa Cattle Breeding Center. Advances in Bio Res 6: 101-105.

- Gebreyohanes MF (2015) Production system and phenotypic characterization of Begait cattle and effects of supplementation with concentrate feeds on milk yield and composition of Begait cows Humera ranch, Western Tigray, Ethiopia. Ph. D. Thesis, Adiss Abeba University, Addis Abeba, Ethiopia.

- Areb E, Silase TG, Giorgis DH, Reti C, Zeleke B, et al. (2017) Phenotypic characterization and production system of Bonga Cattle in its production environment of kaffa zone, southwest Ethiopia. Sky J Agric Res 6: 62-72.

- Habib MA, Bhuiyan AKFH, Amin MR (2010) Reproductive performance of red chittagong cattle in a nucleus herd. Bang J Anim Sci 39: 9-19.

- Melaku M, Zeleke M, Getinet M, Mengistie T (2011) Reproductive Performances of Fogera Cattle at Metekel Cattle Breeding and Multiplication Ranch, North West Ethiopia. Online J Anim Feed Res 1: 99-106.

- Minuye N, Abebe G, Dessie T (2018) On-farm description and status of Nuer (Abigar) cattle breed in Gambella Regional State, Ethiopia. Int J Biodivers Conserve 10: 292-302.

- Ftiwi M (2015) Production system and phenotypic characterization of Begait cattle and effects of supplementation with concentrate feeds on milk yield and composition of Begait cows in Humeraranch, Western Tigray. Ph. D Thesis, College of Veterinary Medicine and Agriculture, Addis Ababa University. Addis Ababa 98p.

- Afridi RJ (1999) Productive performance of Holstein Friesian cattle in North West Frontier Province (NWFP) of Pakistan. Pak Vet J 19: 192-196.

- Hidosa D, Guyo M (2017) Climate Change Effects on Livestock Feed Resources: A Review. J Fisheries Livest Prod 5: 1-4.

- Galmessa U, Dessalegn J, Prasad TA, Kebede LM (2013) Dairy production potential and challenges in Western Oromia milk value chain, Oromia, Ethiopia. J Agri Sustain 22: 1-1.

- Licitra G, Blake RW, Oltenacu PA, Barresi S, Scuderi S, et al. (1998) Assessment of the dairy production needs of cattle owners in Southeastern Sicily. J Dairy Sci 81: 2510-2517.

- Koc A (2011) A study of the reproductive performance, milk yield, milk constituents and somatic cell count of Holstein-Friesian and Montbeliarde cows. Turk J Vet Anim Sci 35: 295-302.

- Javed K, Afzal M, Sattar A, Mirza RH (2004) Environmental factors affecting milk yield in Friesian cows in Punjab, Pakistan. Pak Vet J 24: 4-7.

Citation: Adane Z, Yemane N, Hidosa D (2021) Reproductive and Productive Performance of Indigenous Cattle Breed in Bena-Tsemay District of SoutOmo, South-Western Ethiopia. J Fisheries Livest Prod 9: 312. DOI: 10.4172/2332-2608.1000312

Copyright: © 2021 Adane Z, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 3264

- [From(publication date): 0-2021 - Oct 31, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 2460

- PDF downloads: 804