The Action of Statins on Prostate Cancer: A Clinical Overview

Received: 28-Feb-2019 / Accepted Date: 18-Mar-2019 / Published Date: 25-Mar-2019

Abstract

Background: Statins are one of the most commonly prescribed medicines and are known to lower the level of cholesterol in blood. High cholesterol can increase your risk of developing cardiovascular disease, which includes conditions such as coronary heart disease. This is achieved by the inhibition of the HMG-CoA reductase. Prostate cancer is the most common cancer in men and usually develops slowly, so there may be no signs for many years. Genetic contributions have been associated with prostate cancer. However, no single gene is responsible for prostate cancer. Moreover, there are also reports that link prostate cancer and the use of medications including statins implicated in decreasing prostate cancer risk.

Purpose: The aim of this study is to find the clinical correlation between statins and prostate cancer, in order to conclude if there is positive or negative impact in progression of the disease.

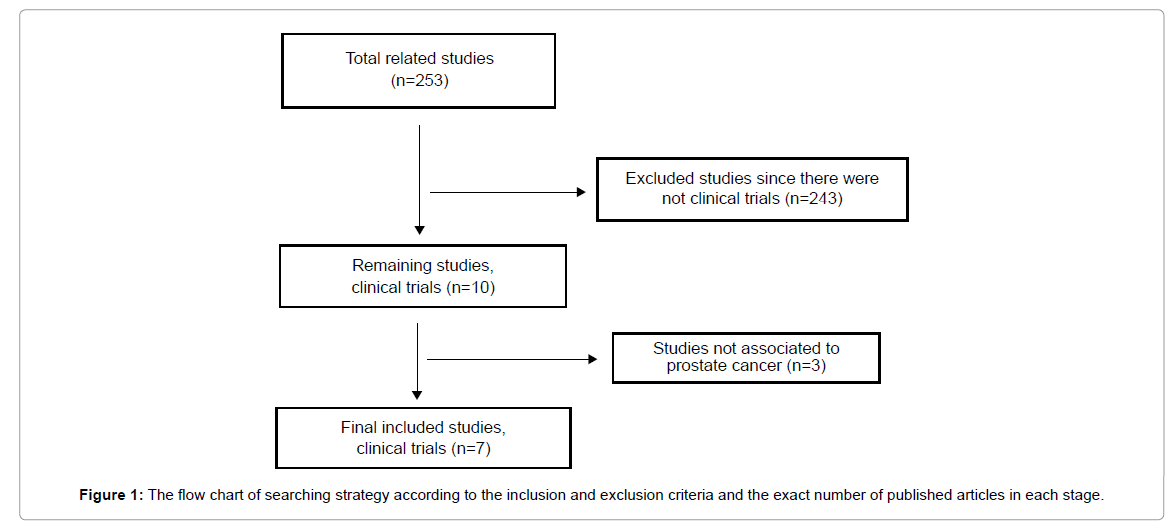

Methods: In the present study we collected only the related clinical trials (2010 to 2017) and we excluded the studies in which statins are not main parameter of the clinical trial.

Outcomes: The effects of statins in prostate cancer, according to previous clinical trials, are not well defined. Evidence suggesting a protective role of statins against prostate cancer are well documented. However, other reports indicate no association with statin medication and prostate cancer progression.

Keywords: Prostate cancer; Cardiovascular disease; Genetics; Cholesterol

Introduction

Cholesterol (lipid) is an important substance found in the human body. From the whole quantity of human cholesterol, 70% is produced by the body and 30% comes from fats that are found in our diet [1]. A small quantity of the consumed fats is absorbed by the small intestine and after metabolic processing cholesterol is produced, which is transported to the liver [2,3]. Cholesterol is then combined with proteins and the resulting complexes that are formed are classified into: chylomicrons (CM), very low density (VLDL), intermediate density (IDL), low density (LDL) and high density (HDL) lipoproteins. These complexes differ in lipid density and in the protein composition [4]. After that, cholesterol is transported to the cells and is used for the structure and the function of cell membranes, for energy, for sterol hormone formation and other important functions.

Most of cholesterol in the human body is stored in to the liver for later use. The cholesterol transported from the cells to the liver, is firstly, mixed with bile fluids and then excreted to the small intestine. Then, 95% of it, is reabsorbed by the small intestine and is transported to the liver. After that, it is stored there or transported through the bloodstream to the cells, in the form of lipoproteins. The remaining 5%, is later removed with the feces.

The most important types of cholesterol are LDL and HDL cholesterol. The first type of cholesterol is characterized as “bad cholesterol”, because when it is not kept in low levels, it causes atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease. The second type of cholesterol is characterized as “good cholesterol”, because it transports the LDL cholesterol in the liver, thus keeping its level to a normal level. The HDL type of cholesterol has, also, other positive effects in human body such as anti-inflammatory properties.

Proteins that are produced by fungi, are commonly used by physicians in order to keep human LDL (low-density lipoprotein) cholesterol to a normal level [5,6]. Statins block the pathway by which cholesterol is produced, a process located in the liver. This is achieved by the inhibition of the HMG-CoA reductase (HMGCR), an enzyme that rules the cholesterol biosynthesis [7]. This increases endothelialderived nitric oxide (NO), a factor that achieves vasodilation, platelet aggregation, vascular smooth muscle proliferation and endothelialleukocyte interactions, the stability of atherosclerotic plaques, the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and reactive oxygen species and the reactivity of platelets. Medical Doctors, mostly prescribe statins in order to help patients with cardiovascular diseases. These substances are also used for the control of a hereditary disease that causes cardiovascular disorders, called hypercholesterolemia, by increasing endothelial-derived nitric oxide (NO). Statins may also affect the regulation of high-density lipoprotein (HDL-C) cholesterol levels. Statins are characterized as pleiotropic because they may have more therapeutic roles, such as anti-inflammatory abilities. On the other hand, some side-effects, such as diabetes, cataract and muscular defects have been attributed to the supplementation of statins.

Prostate is a small, walnut-shaped gland in men, which is responsible for the transportation of sperm by the production of seminal fluids. The most common abnormality in prostate is called prostate cancer (PC). It is a heterogeneous disease with a lot of variety on its phenotype [8]. It seems to be caused by mutations that make the cells proliferate faster [9]. For the detection of prostate cancer, the prostate specific antigen (PSA) and the finger examination test of the rectum are the two most commonly used techniques [10].

Prostate cancer is a disease that draws a lot of attention worldwide. The reason is because it is the most frequently occurring cancer among men, the second type of cancer with the most deaths among men and the fourth most occurring cancer in the whole population [11]. Most men diagnosed with prostate cancer are aged 60+ and each year an average of 1.6 million men across the globe are diagnosed with it. Unfortunately, an average of 25% dies from it [11,12]. The survival rate of localized and regional stages of prostate cancer is almost 100% and the rate for distal stage of prostate cancer is found to be 30%, around 5 years after the diagnosis of it [11,13].

PSA test, measures the amount of a protein produced by both cancerous and noncancerous tissue in the prostate [14]. The prostate specific antigen velocity (PSA V), is a marker that shows the deviation of the PSA measurements, relational to the elapsed time between those measurements [15,16]. In the near future, it can be used statistically, as a predictive value in patients with risk of occurring prostate cancer, but it is yet, a pathologically unreliable source and it cannot be used as a clinical standard [17-19]. On the contrary, it can complement static PSA and through the results of the PSA V, physicians can decide, whether to perform a biopsy for a possible cancer, or not.

Whether statins are beneficial or hazardous to the normal functioning of the prostate gland or have a role in prostate cancer progression is unclear. There is evidence showing that statins may be associated with increased risk of prostate cancer [20]. However, previous studies have shown a different relationship between statin use and prostate cancer risk, which suggests that it has a protective effect against the disease. Therefore, the focus must be for a more thorough study and determine all known clinical trials that have been carried out to identify the direct relationship between prostate cancer risk and statin use.

Methods

The present study is a systematic review of the association of statins supplementation and the prostate cancer. We will try and summarize all clinical trials that evaluate the correlation of statins with prostate cancer out of the reported trials found in PubMed database. We have to admit that not much could be found on this topic.

The search was performed using the words/phrases “statins and cancer”, “statins and prostate”. Next there was a collection only of the published studies involving clinical trials and finally to the studies closely related to the topic. Figure 1 reports the total strategy of date research that has been performed.

Results

In the first study, during 2004 and 2005, a population of 4680 men aged 40 years old and above, with prostate cancer and radian prostatectomy has been selected. The study guided with criteria such as exclusion of non-stage IV disease and not neoadjuvant therapy before surgery that ensured, no resulting effect on the actual procedure according to the protocol of the study. The study was focused on two different aspects of investigation with distinct significance, but both important. In the first one, with biochemical habituation was that the PSA levels were measured as an indicatory biomarker after surgery of prostate cancer. The second type was the clinical examination and observation of the patients during their follow up period from the surgery. The follow up period of the study lasted 5 years and during that period there were regular PSA measurements and checkups of the patients. From the 4860 patients, 1342 received radical prostatectomy, 1184 were included in the analysis for biochemical recurrence and from 1200 which were used for a clinical analysis, 38% used statins before and the 55% after the prostatectomy. In the end, this study concluded that statins may have no preventive properties against prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy [21].

Another study was done regarding the association of prostate cancer in terms of PSA and PSAV and the use of statins or other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Τhey used a population of 699 men. That specific experiment followed the negative biopsy trial by using a randomized, double-blind and placebo-controlled group, to investigate if there is any association between the drugs and the prostate cancer at high risk groups. Additionally, by following the same trial, in another earlier publication they tried to find the effects of selenium significantly at prostate cancer. So, by a questionnaire at baseline and twice-yearly follow-up visits they started the experiment. They counted the PSA values and the PSAV, which are indicator factors, and by a statistical analysis with the use of t-distribution with some specific constants they found some interesting results. By mixing the PSA and PSAV values with the corresponding subjects that used aspirin, NSAIDs or statins, they concluded that there is no significant association between the medication and the high risk of prostate cancer (Algotar et al.).

One more study was trying to identify, if statins, aspirins or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), have an association with prostate cancer and more significantly, if these drugs can lower the risk of prostate cancer. For coming up with the results, they used a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, of 140 men as a data. These 140 men, they were all positive at prostate cancer and agreed to follow an average 3.2 follow up program with selenium use so to determine if the drugs that I already mentioned play a role for lowering the prostate cancer risk. The project began so to investigate the effects of two doses of salinized yeasts compared to a placebo on the progression of prostate cancer. All the data should have had some criteria so to take part at that project and more specifically not to have metastatic cancer, to be less than 85 years old, to have life expectancy for more than 3 years and not to take extra selenium supplements more than 50 μg/day. The data was randomized to placebo group (46 men), to selenium receivers of 200 μg/day (47 men) and to selenium users of 800 μg/day (47 men) for a run period of 30 days with the supplementations. The program had a follow-up for 5 years and checks every 3 months. Furthermore, they categorized the data by a baseline questionnaire that took place to aspirin, NSAIDs and statins users and non-users and also at smokers and non-smokers for each specific drug. They calculated their BMI and the race was divided into two categories. They measured the PSA levels and the PSAV values for each category. Finally, t-tests were performed and multiple linear regression models to observe the PSA before and after medication and some separate model tests for each drug separately. Then, mixed effect models randomly used to assess the effect of medication at the PSAV for each category. After mixed analysis of the results, they concluded that medications have negative association with the PSA velocity but did not achieve statistical significance for any of the three medications [22].

The research team wanted to investigate the correlation of atorvastatin and serum levels of PSA. This non-randomized controlled prospective clinical trial was performed in hypercholesterolemic male patients. Three Groups were used. The first 40 patients had LDL above 190 mg/dl and were treated with 20 mg Atorvastatin per day. The second group was 40 individuals with LDL between 130 mg/dl and 190 mg/dl and were treated with low fat diet. The last 40 patients were the control group with normal LDL levels and without any treatment. They concluded that the short period of Atorvastatin treatment lowered PSA levels. This reduction caused by the direct effect of the drug and not of effect in cholesterol [23].

Furthermore, a randomized, double-blind and placebo-group study cohort study was applied to examine the correlation of total serum cholesterol as well as HDL and prostate cancer. For reaching that conclusion, they selected 29,133 Caucasian people from southwestern Finland all of whom were smokers. All these men were between 50-69 years old and were smoking at least 5 cigarettes per day. Those that could not participate to the experiment, were men that may had experienced a previous cancer or another severe illness or they were using some vitamin supplements daily. Men were categorized by some factorial designs which were given at the beginning of the experiment. They were split to 4 categories, the α-tocopherol (dl-α-tocopherol acetate, 50mg/day), β-carotene (20 mg/day), both supplements and placebo. Then all men answered a questionnaire and some measurements took place along with blood tests. The 3 years follow-up program excluded some people with missing baseline serum information or due to the HDL cholesterol concentration. Then, the 22,836 men and 349,206 person-years followed the 3 years program until the end. Furthermore, with the help of some medical records, some cases where categorized due to level of the cancer. The TNM stage 3 or 4 was aggressive, high was named at stage 3 or higher and higher than 8 were called gleason. Moreover, the level of cholesterol was measured enzymatically with the help of CHOD-PAP method at the baseline and then at the end of the 3 years follow-up program. Finally, Cox proportional hazards modeling was used to estimate the association of the baseline severity of the cancer and the cholesterol in each category and after the 3 years follow-up program.

After result analyses, it was identified that the population of smokers and high cholesterols levels had higher risk of prostate cancer with the high-density lipoproteins found correlated to the reduction of the risk of prostate cancer. In conclusion, some existing hypothesis that statins might be able to reduce the levels of advanced prostate cancer might have a better future research ground [24].

Furthermore, there was an investigation of the serum lipids levels of total cholesterol, LDH, HDL and triglycerides with the use of statins in negative biopsies of patients with prostate cancer in the age of 50-75. Patients with history of prostate cancer or any prostate surgery, atypical small acinar proliferation, users of any lipid-lowering medication high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia and prostate volume of >80 ml, where excluded from the study. There was an association with histological prostate inflammation and the extent of chronic and acuteness of the inflammation was calculated through biopsies. Also, men with missing lipid data seemed to be more likely to have an acute prostate inflammation. The studied population were 6.655 male patients out of which 1.217 (18%) were statin users. The study showed that serum lipid levels, serum levels of total cholesterol, LDL or triglycerides were not associated with either the presence or extent of chronic prostate inflammation. On the other hand, patients with high HDL levels were less likely to have acute prostate inflammation in comparison with those of low HDL levels. Also, statin non-users were less likely to have a chronic prostate inflammation and statin users were less likely to have severe acute inflammation that non-users. The suggestion of this clinical trial was the reduction of prostate cancer risk by statins, through the correlation with inflammation mechanism [25].

Finally, the goal of this research work, was to find out if statins are associated with low-grade or high-grade levels of cancer and if statin plays a key role for prostate’s cancer diagnosis. Firstly, a randomization of 8231 people between 50-75 years old with a serum PSA of 2.5-10 ng ml performed. 4105 enrolled people were on dutasteride, which is a drug for the treatment of PSA and 4126 were on placebo, a type of medication that gives the patient the perception of a real drug. From the 8231 people, 109 were excluded from the experiment because they either did not take drugs, or they had a positive baseline without a reviewed biopsy. As a result, the group was counted 8122 of which 4049 were under dutasteride medication and 4073 under placebo. From the 8122, 1393 had no biopsy, so the population for the experiment remained 6729, that had at least one biopsy, of which 3305 were under dutasteride medication and 3423 were under placebo. At the experiment, the most important biopsies occurred between months 19-24 and 43-48. Furthermore, 1174 were statin users and 5555 were not, a measure that was very important for the experimental results. That statin, by the follow up program from people that had an elevated PSA and a negative baseline biopsy and all the subsequent biopsies that performed independent, is not associated with the diagnose or the high levels of prostate cancer in Table 1 [26].

| Study | Male Population | Follow up | Measurements | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allott et al. [25] | 6.655 | 4 years | total cholesterol, LDH, HDL and triglycerides | Reduce PC risk by statins |

| Chao et al. [21] | 1200 | 5 years | PSA | Not preventive activity of statins |

| Khosropanah et al. [23] | 120 | 1,5 years | PSA, LDL | Reduction activity |

| Algotar et al. [22] | 699 | 4 years | PSA, PSAV | No effect of statins |

| Algotar et al. [22] | 140 | 3,5 years | PSA, PSAV | No association |

| Mondul et al. [24] | 29.093 | 10 years | Total Cholesterol, HDL | Statins decrease the risk of PC |

| Freedland et al. [26] | 8.231 | 4 years | PSA | No association of statins and PC |

Table 1: Male population measurements.

Discussion

Statins are one of the most commonly used drugs by the population. The pleotropic effects of this kind of medication are obvious. Of course, the action of the statins is related with prostate cancer as we discussed previously.

First of all, in this study we summarize the evidence of correlation between statins and prostate cancer. We focused only on the published clinical trials. There were no agreements of the results in these clinical studies about the impact of statins in prevention or in development of prostate cancer. The statins in the majority of the cases are not the only factors that were examined regarding prostate cancer. Furthermore, there were few clinical trials that combined these two parameters. Finally, there were other factors which affected the results of the trials, such us the age of the patients or their smoking habit.

In previous clinical studies, statins use is associated with PSA testing and PSAV levels. In addition, it seems that cholesterol is associated to prostate cancer through androgen production. Therefore, PSA testing and PSA levels as well as castration-independent androgen production are crucial for evaluating the effect of statins on prostate cancer incidence.

From the studies that have been analyzed, two mechanisms are demonstrated about the action of statins in prostate cancer. The first and the most common mechanism is through indirect effect. More specifically, statins have cholesterol –lowering properties, which could be a significant mechanism by which these drugs might inhibit prostate carcinogenesis. Some studies have reported that prostate cancer cells in progressive disease stages, could synthesize androgens from cholesterol and therefore they are independent of testicular androgens [27]. Increasing evidence suggests that androgens and androgen receptors (AR) are significantly involved in castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) progression [28,29]. This evidence is indicated by increased levels of pregnenolone, the first cholesterol-induced steroid precursor of androgens, and by high levels of testosterone and dihydrotestosterone measured in CRPC tumors. In succession, high levels of steroidogenesis lead to androgen receptors activation as involved by the induction of protein expression levels and also by increased AR-regulated protein expression. Cholesterol and its overall regulation within the cell are altered during CRPR, suggesting the hypothesis that regulated cholesterol is likely a steroidogenesis precursor for intratumoral de novo androgen synthesis in the absence of testicular androgens.

The second way is the direct effect of these drugs in prostate cancer cells. In vivo and in vitro studies indicate an antiproliferative, as well as an apoptotic action of the statins. More specifically, statins can induce apoptosis in prostate cancer cells, through five possible mechanisms. Firstly, inhibition of mevalonate production, which is necessary for cholesterol production and isoprenoid synthesis. Secondly, inhibition of Thr-160 phosphorylation of cdk2, which in turn, inhibits its activity, leading to enhancement of P21, a molecule that is very important for apoptosis. An example is, mevastatin inhibition of cdk2 activity, in prostate cancer cell line, PC3 [30]. What’s more, trans regulation and proteosomal degradation of E2F-1, an important oncogene and tumorsuppressor gene, are very important steps in statin-induced apoptosis of prostate cancer cells. Furthermore, inhibition of fanesyl pyrophosphate and geranyl pyrophosphate, precursors of Ras and Rho translation to the cell membrane, which are needed for proliferation and migration of cancer cells. Lastly, another substance, lovastatin, has an effect on early lesions of mammary oncogenesis, through inhibitions of HMGCoA reductase, a rate-limiting enzyme of the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway. But, no such effect was observed in prostate cancer, suggesting that there might be tissue specificity at play [31].

The effects of statins in prostate cancer according to previous clinical trials are not well defined. Evidence that suggest a protective role of the statins against this type of cancer, are faced by other evidence indicative of no association of these two factors. Actually, about half of the clinical trials ended up in mechanisms that affect the prostate cancer, on the other hand the rest studies show minimal or non-correlation. Factors including the lack of statistical adjustment for PSA testing and PSA levels, the short duration of statin use, and the reduced number of prostate cancer cases made it difficult to evaluate the pre-diagnostic and post-diagnostic effects of statin use in prostate cancer.

Future studies are required to examine treatment of various PC cell lines using different statin concentrations to establish a dose and timedependent relationship. Despite a lack of a reported conclusion, some studies suggest that prescriptions of statins in healthy men may have a reduced risk for prostate cancer development. However, physicians should know about the suggested harmful effects of statins on prostate carcinogenesis. Low doses of statins may induce angiogenesis, induced tumor growth and statins may increase CD25+ CD4+ T cell levels suppressing tumor-specific T cell immune responses.

Conclusion

Statins play a crucial role in many functions of the body due to their effect on cholesterol levels that participate in many biological mechanisms. The effect of statins in prostate cancer risk is yet to be clarified. In some previously reported studies, statins have been showed to be correlated with the risk or the development of prostate cancer. In contrast, other studies report no significant status. It is worth mentioning, though, that the studies reporting the positive effects of statins in prostate cancer are the large ones, with a big number of enrolled subjects and with a long time follow up. In conclusion, the impact and the effect of statins in clinical cases of prostate cancer is not well defined to date and future properly designed protocols for double blinded clinical trials have to be performed to give the definite answer to the question.

References

- Kapourchali FR, Surendiran G, Goulet A, Moghadasian MH (2016) The Role of Dietary Cholesterol in Lipoprotein Metabolism and Related Metabolic Abnormalities: A Mini-review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 56: 2408-2415.

- Pikuleva IA, Curcio CA (2014) Cholesterol in the retina: the best is yet to come. Prog Retin Eye Res 41: 64-89.

- Yang F, Chen G, Ma M, Qiu N, Zhu L, et al. (2018) Fatty acids modulate the expression levels of key proteins for cholesterol absorption in Caco-2 monolayer. Lipids Health Dis 17: 32.

- Srivastava N, Cefalu AB, Averna M, Srivastava RAK (2018) Lack of Correlation of Plasma HDL With Fecal Cholesterol and Plasma Cholesterol Efflux Capacity Suggests Importance of HDL Functionality in Attenuation of Atherosclerosis. Front Physiol 9: 1222.

- Oesterle A, Laufs U, Liao JK (2017) Pleiotropic Effects of Statins on the Cardiovascular System. Circ Res 120: 229-243.

- Schonewille M, de Boer JF, Mele L, Wolters H, Bloks VW, et al. (2016) Statins increase hepatic cholesterol synthesis and stimulate fecal cholesterol elimination in mice. J Lipid Res 57: 1455-1464.

- Peisch SF, Van Blarigan EL, Chan JM, Stampfer MJ, Kenfield SA (2017) Prostate cancer progression and mortality: a review of diet and lifestyle factors. World J Urol 35: 867-874.

- Litwin MS, Tan HJ (2017) The Diagnosis and Treatment of Prostate Cancer: A Review. JAMA. 317: 2532-2542.

- Borley N, Feneley MR (2009) Prostate cancer: diagnosis and staging. Asian J Androl 11: 74-80.

- Haas GP, Delongchamps N, Brawley OW, Wang CY, de la Roza G (2008) The worldwide epidemiology of prostate cancer: perspectives from autopsy studies. Can J Urol 15: 3866-3871.

- Pernar CH, Ebot EM, Wilson KM, Mucci LA (2018) The Epidemiology of Prostate Cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 8.

- Ondrusova M, Ondrus D (2017) [Trends in Prostate Cancer Epidemiology in Slovakia - an International Comparison]. Klin Onkol 30: 115-20.

- Atan A, Guzel O (2013) How should prostate specific antigen be interpreted? Turk J Urol 39: 188-193.

- Mikropoulos C, Hutten Selkirk CG, Saya S, Bancroft E, Vertosick E, et al. (2018) Prostate-specific antigen velocity in a prospective prostate cancer screening study of men with genetic predisposition. Br J Cancer 118: e17.

- Vickers AJ, Brewster SF (2012) PSA Velocity and Doubling Time in Diagnosis and Prognosis of Prostate Cancer. Br J Med Surg Urol 5: 162-168.

- Gorday W, Sadrzadeh H, de Koning L, Naugler CT (2015) Prostate-specific antigen velocity is not better than total prostate-specific antigen in predicting prostate biopsy diagnosis. Clin Biochem 48: 1230-1234.

- Patel HD, Feng Z, Landis P, Trock BJ, Epstein JI, et al. (2014) Prostate specific antigen velocity risk count predicts biopsy reclassification for men with very low risk prostate cancer. J Urol. 191: 629-637.

- Vickers AJ (2013) Counterpoint: Prostate-specific antigen velocity is not of value for early detection of cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 11: 286-290.

- Babcook MA, Joshi A, Montellano JA, Shankar E, Gupta S (2016) Statin Use in Prostate Cancer: An Update. Nutr Metab Insights. 9: 43-50.

- Chao C, Jacobsen SJ, Xu L, Wallner LP, Porter KR, et al. (2013) Use of statins and prostate cancer recurrence among patients treated with radical prostatectomy. BJU Int 111: 954-62.

- Algotar AM, Thompson PA, Ranger-Moore J, Stratton MS, Hsu CH, et al. (2010) Effect of aspirin, other NSAIDs, and statins on PSA and PSA velocity. Prostate 70: 883-888.

- Khosropanah I, Falahatkar S, Farhat B, Heidari Bateni Z, Enshaei A, et al. (2011) Assessment of atorvastatin effectiveness on serum PSA level in hypercholesterolemic males. Acta Med Iran 49: 789-794.

- Mondul AM, Weinstein SJ, Virtamo J, Albanes D (2011) Serum total and HDL cholesterol and risk of prostate cancer. Cancer Causes Control 22: 1545-52.

- Allott EH, Howard LE, Vidal AC, Moreira DM, Castro-Santamaria R, et al. (2017) Statin Use, Serum Lipids, and Prostate Inflammation in Men with a Negative Prostate Biopsy: Results from the REDUCE Trial. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 10: 319-326.

- Freedland SJ, Hamilton RJ, Gerber L, Banez LL, Moreira DM, et al. (2013) Statin use and risk of prostate cancer and high-grade prostate cancer: results from the REDUCE study. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 16: 254-259.

- Dillard PR, Lin MF, Khan SA (2008) Androgen-independent prostate cancer cells acquire the complete steroidogenic potential of synthesizing testosterone from cholesterol. Mol Cell Endocrinol 295: 115-120.

- Leon CG, Locke JA, Adomat HH, Etinger SL, Twiddy AL, et al. (2010) Alterations in cholesterol regulation contribute to the production of intratumoral androgens during progression to castration-resistant prostate cancer in a mouse xenograft model. Prostate 70: 390-400.

- Mostaghel EA, Nelson PS (2008) Intracrine androgen metabolism in prostate cancer progression: mechanisms of castration resistance and therapeutic implications. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 22: 243-258.

- Ukomadu C, Dutta A (2003) Inhibition of cdk2 activating phosphorylation by mevastatin. J Biol Chem 278: 4840-4846.

- Shibata MA, Kavanaugh C, Shibata E, Abe H, Nguyen P, et al. (2003) Comparative effects of lovastatin on mammary and prostate oncogenesis in transgenic mouse models. Carcinogenesis 24: 453-459.

Citation: Boutsikos P, Dimitriadis N, Karamanis M, Dardas D, Christodoulou P, et al. (2019) The Action of Statins on Prostate Cancer: A Clinical Overview. J Oncol Res Treat 4: 137.

Copyright: © 2019 Boutsikos P, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Open Access Journals

Article Usage

- Total views: 4040

- [From(publication date): 0-2019 - Dec 19, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 3144

- PDF downloads: 896