Violence against HCWs Working in COVID-19 Health-Care Facilities in Three Big Cities of Pakistan

Received: 06-Apr-2021 / Accepted Date: 07-May-2021 / Published Date: 14-May-2021 DOI: 10.4172/2329-6879.1000355

Abstract

Objectives: The main objectives of the study were to determine the magnitude of violence experienced by health-care workers (HCWs) working in COVID 19 healthcare facilities, learn from the experiences of HCWs and persons accompanying the patients and identify interventions that can help in protecting HCWs.

Methodology: This was a mixed-methods study with a concurrent triangulation design. A cross sectional survey was conducted with 356 HCWs including doctors, paramedics and laboratory technicians in 24 COVID-19 healthcare facilities in three provincial capital cities of Pakistan. To explore the experiences of HCWs regarding violence and stigma associated with treating COVID-19 patients, eighteen in-depth interviews (IDIs) were conducted with doctors and laboratory technicians. To explore the positive and negative perceptions of community, 15 IDIs were conducted with general public and persons accompanying the admitted patients.

Results: Overall 41.9% reported having experienced some form of violence in the last two months. More commonly experienced forms of violence included verbal (33.1%), being falsely accused (12.9%), being stigmatized (12.4%) while less commonly reported forms included physical violence (6.5%) and being threatened (6.2%). According to experiences of the interviewees, the root cause of violence was the misconception spread on social media that COVID-19 was a conspiracy and people were being unnecessarily tested and admitted.

Conclusion: A high proportion of HCWs shared their experiences of violence against them during the peak days of the outbreak. Specific strategies need to be adopted to protect the frontline workers which include dispelling the existing myths and improving gaps in quality of care.

Keywords: COVID 19 Care; Health workers; Violence; Safety and security

Introduction

The pandemic of COVID-19 originated from Wuhan, China in late 2019 [1]. Healthcare Workers (HCWs) are at the frontline of this response against the pandemic and are dealing with a new and unusual challenge, psychologically making them vulnerable to reduced work performance [2]. The stress of getting infected and the stigma of working in a potentially infectious environment has affected the mental health of health-care workers (HCWs) negatively [3]. While in highincome countries an outpour of public support towards the HCWs has been observed, reports on violence and discrimination against HCWs continue to emerge in low-resource contexts.

In countries like Pakistan with meagre resources and overburdened health systems, it poses major public health challenges for the community and all professions and policy makers [4]. Because of proliferation in cases and deaths and the strict isolation protocols of managing the cases and dealing with deaths, the HCWs are vulnerable to encountering events of verbal and physical violence against them [5,6]. An already stressed HCW, due to tough nature of job and social stigma, is faced with another challenge of dealing with angry attendants who lack understanding and knowledge of protocols of treating a highly infectious disease and the management of dead bodies in this situation.

No focused study has investigated the issue of violence against HCWs providing COVID-19 health-care services. Only a few commentaries have highlighted this issue in the peer reviewed journals [7-9]. The purpose of this study was to determine the magnitude of violence experienced by HCWs working in COVID-19 health-care facilities in three cities of Pakistan, learn from their experiences and identify interventions that can help in protecting HCWs.

Methodology

This was a mixed methods study with a concurrent triangulation design (QUAL-QUAN).

Quantitative Survey

A cross sectional survey was conducted with HCWs including doctors, paramedics and staff in screening and diagnostic laboratories in public and private COVID-19 health-care facilities in three provincial capital cities of Pakistan i.e. Karachi, Lahore and Peshawar. From each city, HCWs from 8 health-care facilities were approached, 4 from public sector and 4 from private sector, and 15 HCWs (5 doctors, 5 paramedics and 5 laboratory technicians) were surveyed from each unit. A total of 360 HCWs were included i.e. 120 from each city.

The list of doctors and paramedics working in the selected units was developed by obtaining their email addresses and contact numbers from their peers. All of them were invited online or through phone and those consenting to participate were interviewed. Only those HCWs were included who had worked for at least 15 days in a COVID-19 care isolation ward or intensive care unit or screening and diagnostic laboratory. A structured questionnaire was used to obtain information on frequency of violence experienced, its nature, causes and consequences. Questionnaire was adopted from previous survey done on violence against HCWs at national level [10]. Violence was defined as experience of any event of verbal violence or physical violence or facility damage, false accusation or stigma. Recall period of last two months was based on high burden of COVID-19 patients in Pakistan in months of May and June. Data was collected by trained data collectors and all trainings were conducted online. Data was entered and analyzed on SPSS version 20.

The relationship of different factors including age, gender, work experience, type of hospital, place of posting, cadre of HCWs, number of days worked in COVID-19 health-care facility and psychosocial effect index with experience of physical violence, verbal violence, being falsely accused and being stigmatized were analyzed using multivariate logistic regression. Adjusted odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals were computed to express the relationship.

Qualitative Methods

To explore the experiences of HCWs regarding violence associated with treating COVID-19 patients and its psychosocial effects, indepth interviews (IDIs) were conducted with doctors and laboratory technicians. In all 12 IDIs were conducted with doctors in the 3 cities and 6 IDIs were conducted with laboratory technicians after which point of saturation was reached. All the HCWs interviewed were included if they had experienced some form of violence in the last two months. To explore the positive and negative perceptions of community, 9 IDIs were conducted i.e. 3 in each city with general public and 6 IDIs were conducted with persons accompanying the admitted patients in COVID-19 isolation units and intensive care units after which point of saturation was reached.

The IDIs were conducted online by three trained research fellows who had training in qualitative research and had previous experience of conducting IDIs. All the participants were formally approached and informed consent was obtained from all participants. The IDIs were recorded online and transcribed in local language and later translated in English. Thematic content analysis was done by two qualitative research experts.

Results

Data was collected from 360 participants and final analysis was done on 356 excluding 4 participants with missing information. The mean age of the participants was 30.17 years, with 61.2% males and 38.8% females. Overall 41.9% reported having experienced some form of violence in the last two months (Table 1).

| Verbal Violence | 33.1% (118) |

| Falsely Accused | 12.9% (46) |

| Stigma | 12.4% (44) |

| Physical Violence | 6.5% (23) |

| Threat | 6.2% (22) |

| Damage to facility | 1.7% (6) |

| Shown Weapon | 0.6% (2) |

| Any Form of Violence | 41.9% (149) |

Table 1: Nature of Violence Experienced by HCWs working in COVID-19 health-care facilities in the last two months (n=356).

Main reasons and perpetrators for the last event of different types of violence experienced in the last two months

According the quantitative data, the most common reasons of physical and verbal violence included emotional reaction to death, concern about critical patient or sudden collapse of patient, dissatisfaction with quality of care and treatment, delay in care and unwillingness of the attendants to admit the patient. Attendants were the main perpetrators followed by patients. The reasons of being falsely accused included worsening of the condition of patient, doing unnecessary admissions or tests, giving wrong treatment, giving false positive report and overcharging for care.

According to findings of qualitative interviews, the root cause of violence was the misconception spread on social media. A resident doctor from private hospital of Peshawar expressed, “There was one news that went viral that the doctors in COVID-19 treatment units are giving poisonous injections to kill patients. Even my own relatives were of the point of view that we are intentionally admitting patients and are paid for falsely admitting them”. The misperception created distrust in HCWs and there was reluctance among people to undergo screening test or admit the patients to COVID-19 care units to avoid social stigma or being victimized.

Among the issues related to patient shifting and admission, most important was that people were not aware of where to take the patient/ suspected patient of COVID-19. There were also complains of helplines not responding to calls of the people. Besides that, another factor that agitated the people was reaching the hospital and being refused for admission during the peak days of the outbreak. While admissions and tests were not charged in public hospitals, interviewees also complained about high costs of admissions and tests in private facilities.

The issues related to patient care aroused due to patient behaviour and quality of care. Specific behavioural reasons included resistance to compliance with extremely strict patient access and infection prevention control protocols in the hospitals. One of the doctors from Peshawar complained, “When we stopped them to meet their patient physically, they shouted and abused us”. Specific factors related to quality of care included confusion on treatment protocols, reluctance of HCWs to spend time with COVID-19 patients to protect themselves and lack of periodic updates on patient condition due to high burden further exacerbated the situations. An attendant from Lahore raised the point of lack of communication on patient progress, “We did not get any information about the patient, we did not know what is going on, and this made us restless”.

Finally, the issues related to service outcomes also aroused due to patient behaviour and quality of care. Specific reasons related to behaviour in COVID-19 care units were demands of attendants of handing over dead body immediately and not mentioning COVID-19 as cause of death. Similarly, among reasons related to the quality of care, due to high burden of patients, there were complains of premature discharge of the patients to make space for new patients and delays in test reports of patients.

Predictors of violence against HCWs working in COVID-19 facilities

Table 2 shows the finding of multivariate logistic regression analysis on adjusted relationship of different groups of HCWs with four main types of violence experienced. Age, work experience and type of hospital did not show any significant relationship with any form of violence experienced. Females were significantly less likely (OR=0.29; 95% CI=0.08-0.97) to experience physical violence. In reference to lab workers, HCWs in intensive care units were significantly more likely (OR=2.11; 95%CI=1.01-4.41) to experience verbal violence. Higher numbers of workdays in the last two months in COVID-19 care facilities were significantly positively associated with experiencing verbal violence.

| Verbal Violence OR (95% CI) |

Physical Violence OR (95% CI) |

Stigma OR (95% CI) |

Falsely Accused OR (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years 21-29 (n=213) 30 and above (n=143) |

1.00 1.08 (0.57-2.06) |

1.00 0.51 (0.14-1.83) |

1.00 1.18 (0.46-3.03) |

1.00 0.65 (0.23-1.77) |

| Gender Male (n=218) |

1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Female (n=138) | 0.68 (0.39-1.19) | 0.29 (0.08-0.97) • | 1.22 (0.56-2.66) | 0.92 (0.42-1.99) |

| City Karachi (n=115) Peshawar (n=123) Lahore (n=118) |

1.00 0.80 (0.44-1.46) 0.77 (0.42-1.40) |

1.00 0.46 (0.15-1.40) 0.30 (0.08-1.07) |

1.00 2.21 (0.89-5.51) 1.95 (0.76-5.03) |

1.00 |

| 0.36 (0.15-0.88) • 0.36 (0.15-0.85) • |

||||

| Hospital Public (n=184) Private (n=172) |

1.00 0.96 (0.59-1.57) |

1.00 1.09 (0.44-2.72) |

1.00 0.67 (0.33-1.38) |

1.00 |

| 1.06 (0.52-2.16) | ||||

| Place of Posting Diagnostic Laboratory (n=98) Isolation Ward (n=144) Intensive Care Unit (n=114) |

1.00 1.28 (0.61-2.67) 2.11 (1.01-4.41)• |

1.00 0.99 (0.24-3.99) 1.80 (0.39-5.65) |

1.00 2.06 (0.71-5.97) 1.82 (0.60-5.45) |

1.00 0.75 (0.21-2.68) 2.53 (0.79-8.08) |

| Nature of Job Lab Workers (n=98) Doctors (n=133) Paramedics (n=125) |

1.00 1.63 (0.93-2.87) 1.23 (0.69-2.21) |

1.00 1.24 (0.43-3.55) 0.91 (0.29-2.79) |

1.00 1.35 (0.57-3.20) 1.77 (0.76-4.11) |

1.00 |

| 4.27 (1.69-10.75) 1.48 (0.52-4.15) |

||||

| Work experience in years 1-4 (n=212) 5-9 (n=76) 10 and above (n=68) |

1.00 1.40 (0.72-2.72) |

1.00 1.41 (0.40-4.99) |

1.00 1.08 (0.40-2.87) |

1.00 1.66 (0.58-4.76) |

| 1.01 (0.43-2.36) | 1.63 (0.31-8.58) | 1.28 (0.41-4.01) | 3.21 (0.91-11.34) | |

| Number of days worked in COVID-19 care facility 15-29 (n=103) 30-44 (n=107) 45-59 (n=146) |

1.00 2.91(1.48-5.69) •• 3.01 (1.56-5.79) •• |

1.00 2.47 (0.56-10.81)) 3.80 (0.93-15.48) |

1.00 0.80 (0.20-2.19) 3.80 (0.93-15.48) |

|

| 1.00 0.71 (0.27-1.83) |

||||

| 1.55 (0.65-3.65) |

Table 2: Relationship of different groups of HCWs with different types of violence (n=356).

Discussion

No focused studies on COVID-19 workers are available to compare the figures on magnitude of violence faced by COVID-19 workers with other countries. However, the figures on burden of different types of violence are consistent with recently published large scale multi city surveys in Pakistan and Turkey [10,11]. However, it should be noted that this survey is based on only two month recall while the large scale surveys quoted above had recall periods of six months and one year respectively. It is likely that frequencies of experiencing violence could have been much higher given longer recall time in this study. The multivariate logistic regression also shows that HCWs who spent higher number of days in COVID-19 care facilities were significantly more likely to experience both physical and verbal forms of violence.

Apart from specific reason of violence against HCWs due to COVID-19 mentioned in the results, general reasons reported in this study are similar to reasons reported in previous studies in low resource settings [12-17]. However, it is assumed that these factors were compounded during the peak months of the outbreak with heavy burden on an already weak health system.

Among the predictors of violence, age and work experience did not show any significant relationship with any form of violence experienced although positive trends were observed for the more experienced. This could be due to the fact that senior HCWs were more involved in decision making and interaction with COVID-19 suspects and patients. Previous studies have also shown mixed results on relationship of work experience and violence with some reporting positive association [18,19] while others reporting negative association [20,21]. Females were significantly less likely to experience physical violence and the trend was also negative for verbal violence as well. This is consistent with findings of studies in Asian and African countries [22-24]. The occurrence of events was strikingly similar in both public and private facilities. Previously, public facilities have reported higher occurrence of violence in comparison to private facilities in Pakistan [10,12] owing to better facilities and security policies. However, high burden and costs of COVID-19 care in private facilities may have neutralized this effect in this study. Unsurprisingly, events of violence were significantly higher experienced by HCWs working in intensive care units. Literature also reports higher occurrences of violence in emergency settings [25,26].

As per our literature review, this is the first study which has investigated the reasons and effects of violence against COVID-19 workers in a developing country. The inclusion of persons utilizing the services along with HCWs also brings in conflicting perspectives of provider and user together.

Limitations of this study include convenience sampling, which reduces the overall generalizability. Second, in response-based studies, there is always a chance of under-reporting and over-reporting bias. However, since the recall period in this study was only two months, it is likely that the incidents reported would have a minimum memory bias.

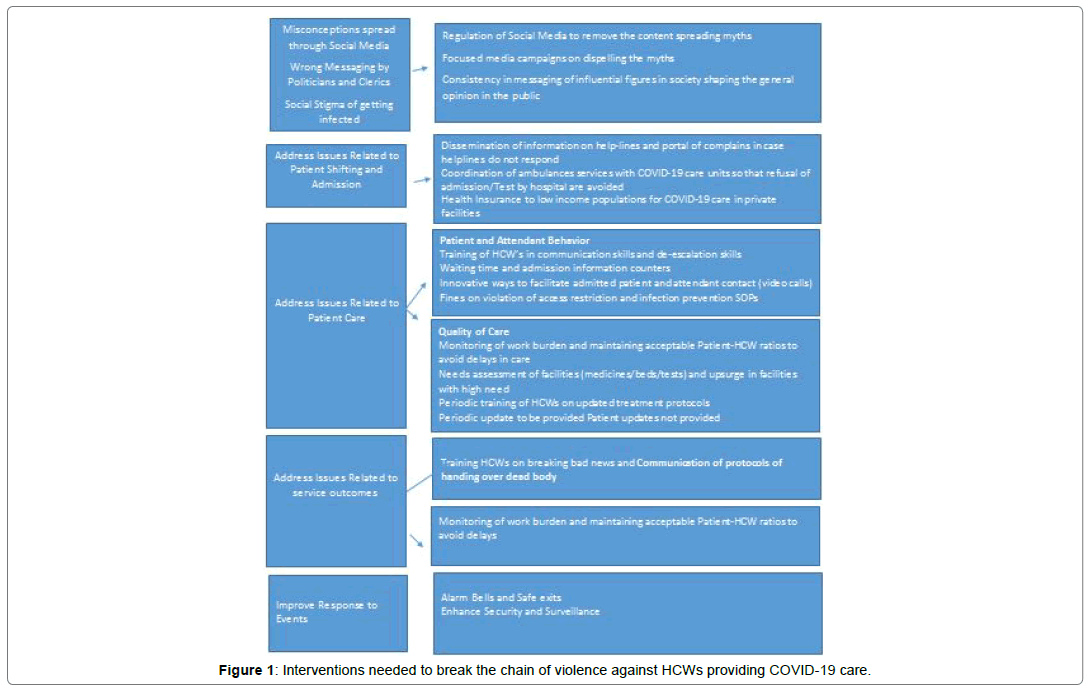

Although infection rates have come down in Pakistan, the chances of recurrence remain. Therefore preparing for prevention of possible upsurge of events of violence should be a top priority to keep the HCWs motivated. These recommendations may also be applied in similar developing countries where infection rates are high currently. Figure 1 summarizes the set of interventions needed to protect the HCWs in COVID-19 care facilities.

Conclusion

A high proportion of HCWs shared their experiences of violence against them during the peak days of the outbreak. Specific strategies need to be adopted to protect the frontline workers which include dispelling the existing myths and improving gaps in in quality of care.

Ethical Considerations

The study was approved by ethical review committee of Jinnah Sindh Medical University. Informed consent was obtained from all the HCWs who participated in the study. The identities of all individuals and institutions have been kept anonymous and confidential.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests

Funding

The research was funded by Health Care in Danger project of International Committee of Red cross.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the contribution of our data collectors, institutions and all participants of the study

Author Contributions

Shiraz Shaikh, Mirwais Khan and Lubna Ansari Baig conceived the idea, developed the first draft of the proposal, conducted the trainings of data collectors, supervised and analyzed the data and wrote the first draft of discussion.

Muhammad Naseem Khan and Mahwish Arooj assisted in development of methodology of the proposal, supervision of data collection, monitored data entry and contributed in interpretation of data.

Sana Hayat and Hira Tariq facilitated trainings, supervised and checked data and provided technical input in analysis and interpretation of data. They also conducted literature search, assisted in development of the research tool and designing the trainings. They also did the data entry and contributed in developing tables and graphs of the results.

References

- Gorbalenya AE, Baker SC, Baric RS, de Groot RJ, Drosten C, et al. (2020) "The species Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2. Nat Microbiol5: 536.

- Liu TB, Chen XY, Miao GD. (2003) Recommendations on diagnostic criteria and prevention of SARS-related mental disorders. J Clin Psychol Med 13:188–191.

- Xiang TY, Yang Y, Li W, Zhang L. (2020) Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel corona-virus outbreak is urgently needed. J Lancet Psychiatry 7: 228-229.

- Bastani P, Bahrami MA. (2020) COVID-19 related misinformation on social media: a qualitative study from Iran. J Med Internet Res.

- Bhatti MW (2020) Why are Karachi’s hospitals getting more DOAs, near-death patients? The News

- Dawn News. (2020) Mob vandalizes JPMC ward after hospital’s refusal to hand over Covid-19 patient’s body.

- Gan Y, Chen Y, Wang C, Latkin C, Hall BJ. (2020) The fight against COVID-19 and the restoration of trust in Chinese medical professionals. Asian J Psychiatr 51:102072.

- McKay D, Heisler M, Mishori R, Catton H, Kloiber O. (2020) Attacks against health-care personnel must stop, especially as the world fights COVID-19. Lancet 395:1743-1745.

- RodrÃguez BR, Cartujano BF, Cartujano B, Flores YN, Cupertino AP, et al. (2020) The Urgent Need to Address Violence Against Health Workers During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Med Care 58:663.

- Shaikh S, Baig LA, Hashmi I, Khan M, Jamali S, et al. (2020) The magnitude and determinants of violence against healthcare workers in Pakistan. BMJ global health 5:e002112.

- Pinar T, Acikel C, Pinar G, Karabulut E, Saygun M, et al. (2017) Workplace violence in the health sector in Turkey: A national study. J Interpers Violence 32:2345-2365.

- Baig LA, Shaikh S, Polkowski M, Ali SK, Jamali S, et al. (2018) Violence against health care providers: a mixed-methods study from Karachi, Pakistan. J Emerg Med 54:558-566.

- Baig LA, Ali SK, Shaikh S, Polkowski MM. (2018) Multiple dimensions of violence against healthcare providers in Karachi: results from a multicenter study from Karachi. J Pak Med Assoc 68:1157-1165.

- Mirza NM, Amjad AI, Bhatti AB, Shaikh KS, Kiani J, et al. (2012) Violence and abuse faced by junior physicians in the emergency department from patients and their caretakers: a nationwide study from Pakistan. J Emerg Med 42:727-733.

- Algwaiz WM, Alghanim SA. (2012)Violence exposure among health care professionals in Saudi public hospitals. A preliminary investigation. Saudi Med J 33:76-82.

- Kumar PN, Betadur D, Chandermani. (2020) Study on mitigation of workplace violence in hospitals. Med J Armed Forces India 76(3):298-302.

- Shafran TS, Chinitz D, Stern Z, Feder BP (2017). Violence against physicians and nurses in a hospital: How does it happen? A mixed-methods study. Israel journal of health policy research. 6:1-2.

- Hamdan M, Asma AH, Abu Hamra A. (2015) Workplace violence towards workers in the emergency departments of palestinian hospitals: a cross-sectional study. Hum Resour Health 13:28.

- Li Z, Yan CM, Shi L, Mu HT, Li X, et al. (2017) Workplace violence against medical staff of Chinese children's hospitals: a cross-sectional study. PloS one. 12:e0179373.

- Zafar W, Siddiqui E, Ejaz K, Shehzad MU, Khan UR, et al. (2013) Health care personnel and workplace violence in the emergency departments of a volatile metropolis: results from Karachi, Pakistan. J Emerg Med 45:761-772.

- Yenealem DG, Woldegebriel MK, Olana AT, Mekonnen TH. (2019) Violence at work: determinants & prevalence among health care workers, northwest Ethiopia: an institutional based cross sectional study. Annals Occup Environ Med 31:1-7.

- Muzembo BA, Mbutshu LH, Ngatu NR, Malonga KF, Eitoku M, et al. (2014) Workplace violence towards Congolese health care workers: a survey of 436 healthcare facilities in Katanga province, Democratic Republic of Congo. J Occup Health 14-0111.

- Alâ€Omari H. (2015) Physical and verbal workplace violence against nurses in Jordan. Int Nurs Rev 62:111-118.

- Sun P, Zhang X, Sun Y, Ma H, Jiao M, et al. (2017) Workplace violence against health care workers in North Chinese hospitals: a cross-sectional survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health 14:96.

- Behnam M, Tillotson RD, Davis SM, Hobbs GR. (2011) Violence in the emergency department: a national survey of emergency medicine residents and attending physicians. J Emerg Med 40:565-579.

- Zhang L, Wang A, Xie X, Zhou Y, Li J, et al. (2017) Workplace violence against nurses: A cross-sectional study. Int J Nurs Stud 72:8-14.

Citation: Shaikh S, Khan M, Baig LA, Khan MN, Arooj M, et al. Violence against HCWs Working in COVID-19 Health-Care Facilities in Three Big Cities of Pakistan. Occup Med Health Aff 9.355. DOI: 10.4172/2329-6879.1000355

Copyright: © 2021 Shaikh S, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 2803

- [From(publication date): 0-2021 - Oct 04, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 1979

- PDF downloads: 824