Beliefs in Effectiveness of Various Smoking Cessation Interventions among Chinese Adult Smokers

Received: 15-Sep-2011 / Accepted Date: 31-Oct-2011 / Published Date: 16-Nov-2011 DOI: 10.4172/2161-1165.1000106

Abstract

Background: Formal smoking cessation interventions including pharmacologic and behavioral interventions have been well known among Chinese smokers, however, the utilization of such interventions is not widely adopted. Lack of belief in the effectiveness of these interventions may be a probable reason. The objective of this study was to identify potential predictors affecting smokers’ beliefs in the effectiveness of smoking cessation interventions among Chinese adult smokers.

Methods: A self-reported survey was distributed using convenience sampling among adult smokers over 18 years at two sites in China. Potential predictors, including socio-demographic characteristics, health conditions, and addiction level that affect smokers’ beliefs in the effectiveness of either pharmacologic or behavioral smoking cessation interventions were explored using multivariate logistic regression.

Results: A total of 365 smokers were identified and considered as cohort in this analysis. Higher income ($450/ month or more vs. less than $450) (odds ratio (OR): 3.05, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.38-6.72), studying in private schools (OR: 4.87, 95% CI: 1.06-22.39) and preferring to inhale when smoking (OR: 1.95, 95% CI: 1.07-3.57) were associated with having beliefs in the effectiveness of pharmacological products. Heavy smokers (smoke 20 cigarettes/ day or more vs. less than 20) (OR: 0.36, 95% CI: 0.18-0.71) and age group (≥40 years old vs. 18-40 years old) (OR: 0.36, 95% CI: 0.18-0.72) were negatively associated with having beliefs in the effectiveness of behavioral methods.

Conclusions: The rates of believing in the effectiveness of various smoking cessation interventions among Chinese adult smokers ranged from approximately 30% to 60%. The utilization of formal cessation interventions including both pharmacologic and behavior methods can be limited by smokers’ beliefs which should be considered when choosing a smoking cessation intervention.

Keywords: Predictor; Smoking cessation interventions; Effectiveness; China.

Abbreviations

NRT: Nicotine Replacement Therapy; OTC: Over- The-Counter; OR: Odds Ratio; CI: Confidence Interval; WHO: World Health Organization; CDC: Centers for Disease Control

Introduction

Smoking remains the leading preventable cause of morbidity and mortality [1]. With an estimated 1.22 billion smokers worldwide, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported that the global mortality of smoking was 5.4 million in year 2004 [2]. Cigarette smoking greatly increases the risk of lung cancer and heart attacks (coronary heart disease and acute myocardial infarction) [3-6]. It is also a risk factor for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cancers, including pharyngeal, esophageal, bladder, laryngeal, and pancreatic cancer [7-9]. Life expectancy of a regular smoker is roughly 7-13 years shorter than that of a non-smoker on average [10].

In China, approximately 3000 deaths/day were attributable to smoking in 2005, reaching almost seven million deaths caused by smoking [11,12]. With a prevalence of 67% among males in China, smoking is estimated to kill approximately one-third of Chinese men who are under 30 years old [12]. Annually, over 320 million smokers consume an approximate 1.7 trillion cigarettes accounting for 40% of cigarettes smoked all over the world, and costing five billion U.S. dollars in 2000, 3.1% of China’s national health expenditures [12-14].

Smoking cessation is highly recommended by public health departments of various organizations, like WHO and Centers for Disease Control (CDC) [15,16]. However, it leads to physiological symptoms of withdrawal caused by nicotine dependence, which involves craving for tobacco and may lead to failing an attempt to quit smoking [17].

There are mainly two categories of available smoking cessation interventions, pharmacologic and behavioral interventions [18]. Pharmacologic methods consist of five forms of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) and two prescription medications, an antidepressant and a nicotinic receptor agonist [19]. Behavioral methods consist of consulting from health care programs or/and educational programs, and mass media interventions [20]. Both of these two methods have been reported successful in helping a smoker quit smoking [21,22].

The International Tobacco Control (ITC) China project conducted by Yang et al. [23] showed that in China, many smokers were aware of pharmacologic and behavioral interventions, however, underutilization remains common, mainly caused by lack of belief in effectiveness of these pharmacologic and behavioral interventions [24-26]. As suggested by the theory of planned behavior [27], having beliefs in effectiveness of an intervention such as a positive attitude may directly influence the decision to use that intervention. To our knowledge, literature evaluating the beliefs of smokers regarding effectiveness of smoking cessation interventions is scarce [24]. The objective of this study was to examine smokers’ beliefs in potential effectiveness of available smoking cessation interventions among Chinese adults. Understanding these opinions from a smoker’s perspective within the unique Chinese culture are important in determining subpopulations where specific interventions can be effective and are critical in designing and advocating cuturally appropriate interventions to help smokers quit smoking.

Methods

Study design and data source

A cross-sectional, convenience sampling study utilizing a selfreported survey was conducted among adults (over 18 years), in China between October 30, 2009 and February 5, 2010.

The questionnaire was adapted from previously used surveys [28,29], translated into Chinese. Translation and back-translation were used to obtain a conceptual equivalence from English to Chinese. The survey was distributed at two sites in China, a government agency and a trading company. These two sites were used to include adult participants of diverse socio-demographic characteristics. Adults who visited these two sites were asked if they were willing to anonymously participate in completing a 15-20 minute survey regarding smoking. If they agreed, they were given a survey and asked to drop the completed survey in a sealed box that was available at each of these sites. Informed consent was provided with the survey and participation was voluntary. The study was approved by the Institution Review Board of University of Houston for the Protection of Human Subjects.

The questionnaire inquired about: socio-demographic characteristics, health conditions, addiction level, as well as beliefs regarding effectiveness of different smoking cessation interventions. Various socio-demographic characteristics including gender, age, marital status, residence, monthly income, employment status, and educational level were examined. Addiction level consisted of six questions: ‘How many cigarettes do you smoke every day?’, ‘How soon after you wake up do you smoke your first cigarette?’, ‘Which cigarette would you most hate to give up?’, ‘Do you find it hard to keep from smoking cigarettes in places where you are not allowed to smoke?’, ‘Do you smoke if you are sick in bed?’, and ‘Do you smoke more during the first two hours of the day than during the rest of the day?’. ‘Smokers’ were defined as those who smoked at least one cigarette in the past 30 days.

Outcome measures

Two main outcome variables were identified. The first outcome variable was whether or not smokers believed that pharmacologic methods (including either NRT products or cessation medications) were effective smoking cessation strategies. The second outcome variable was whether or not smokers believed that behavioral methods (including consulting from health care programs or/and educational programs, and mass media interventions) were effective smoking cessation strategies.

In pharmacologic methods, NRT products are over-the-counter (OTC) drugs, while cessation medications need prescriptions. To further analyze the beliefs in pharmacologic methods, the first outcome that whether smokers believed that NRT (including gum, patch, lozenge, spray, and inhaler) or cessation medications (including antidepressant, Bupropion, and nicotinic receptor agonist, Varenicline) was effective in smoking cessation was tested individually. Beliefs in the effectiveness of various interventions were defined as ‘yes’ if they ‘agree’ or ‘strongly agree’ that ‘the smoking cessation intervention would be effective in helping their ability to quit smoking’, while ‘no’ if they ‘disagree’ or ‘strongly disagree’.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics and chi-square test were performed to examine the association of smokers’ beliefs in effectiveness of different smoking cessation interventions with socio-demographic characteristics, including age, gender, marital status, residency, employment status, education levels, smoking status and addictive levels.

Univariate logistic regression analyses were carried out between participants’ characteristics and outcome variables. Independent variables at a priori significance level of 0.05 were selected and results were presented as unadjusted odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were carried out to determine predictors of beliefs in effectiveness of smoking cessation interventions, including NRT products, smoking cessation medications, pharmacologic and behavioral interventions. Variables with a probability of less than 0.2 in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate logistic regression models and backward elimination to arrive at the final models after assessing colinearity between the independent variables. Results of multivariate logistic regression models were presented as adjusted OR with 95% CI. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) statistical package at a priori significance level of 0.05.

Results

A total of 1100 surveys were distributed. The response rate was 67.3% with 780 surveys returned. Forty inefficient surveys were removed because 12 participants returned a blank survey, two participants submitted the survey with pages removed, 19 participants returned partially completed surveys, and the seven remaining completed surveys could not be included due to inconsistency in responses. Among the 710 completed surveys, 51.4% (n=365) smokers were identified and considered as a cohort in our analysis.

Sample characteristics

In our study, majority of respondents were male smokers (90.0%, n=314), aged between 18 and 24 years (66.0%, n=241), and married (72.9%, n=266). The residency distribution consisted of 43.8% (n=160) of respondents living in rural areas and 56.2% (n=205) of respondents living in urban areas. Majority of respondents were employed (71.5%, n=261) and had an average monthly income from all sources of less than $450 (81.4%, n=297). Approximately 31% (n=113) of respondents were categorized as heavy smokers, measured as ‘reported taking 20 cigarettes or more per day’, whereas 69% (n=252) of respondents reported taking less than 20 cigarettes per day. Socio-demographic characteristics of the sample population are shown in Table 1.

| Participant Charateristics | Frequency (N=365) | Percentage (%) |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 35 | 10.0 |

| Male | 330 | 90.0 |

| Age | ||

| ≥40 | 124 | 34.0 |

| 18-40 | 241 | 66.0 |

| Marital status | ||

| Not married | 99 | 27.1 |

| Married | 266 | 72.9 |

| Residency | ||

| Urban | 205 | 56.2 |

| Rural | 160 | 43.8 |

| Monthly income | ||

| <$450 | 297 | 81.4 |

| ≥$450 | 68 | 18.6 |

| Employment status | ||

| Employed | 261 | 71.5 |

| Unemployed | 104 | 28.5 |

| Education level | ||

| Less than College | 233 | 63.8 |

| College/University and above | 132 | 36.2 |

| High school attribute | ||

| Public | 277 | 89.3 |

| Private | 33 | 10.7 |

| Smoking status | ||

| Heavy smoker (≥20 cigarettes/day) | 113 | 31.0 |

| <20 cigarettes/day | 252 | 69.0 |

Table 1: Social-Demographic Characteristics of Chinese Adult Smokers of the Sample Population

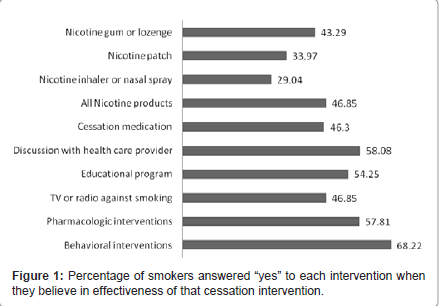

Figure 1 shows the frequency distribution of the beliefs in effectiveness of different smoking cessation interventions among smokers. Among 365 smokers, 46.9% (n=171) believed NRT products (nicotine gum, patch, and/or inhaler) would be effective and 46.3% (n=169) believed cessation medications would be beneficial, respectively. Nicotine gum or lozenge was favorable in 43.3% (n=158) of smokers, followed by nicotine patch (34.0%, n=124) and nicotine inhaler or nasal spray only (29%, n=106). More than half of the smokers (58.1%, n=212) believed that discussions with health care providers would be effective, followed by educational program (54.3%, n=198), and TV or radio program against smoking (46.9%, n=171). Smokers' characteristics are summarized in Table 2 including results of chi-square test with previous defined outcome variables.

| Participant Characteristics | Total N (%) | NRT Products | Cessation Medications | Pharmacologic Methods | Behavioral Methods | ||||

| N (%) | p-value | N (%) | p-value | N (%) | p-value | N (%) | p-value | ||

| Gender | |||||||||

| Male | 314(90.0) | 152(48.4) | 0.53 | 150(47.8) | 0.93 | 188(59.9) | 0.34 | 221(70.4) | 0.57 |

| Female | 35(10.0) | 15(42.9) | 17(78.6) | 18(51.4) | 23(65.7) | ||||

| Age | |||||||||

| 18-40 | 241(66.0) | 129(53.5) | 0.01** | 118(49.0) | 0.16 | 151(62.7) | 0.01 | 178(73.9) | 0.01** |

| ≥40 | 124(34.0) | 42(33.9) | 51(41.1) | 60(48.4) | 71(57.3) | ||||

| Marital status | |||||||||

| Married | 266(72.9) | 119(44.8) | 0.18 | 125(47.0) | 0.66 | 151(56.8) | 0.51 | 175(65.8) | 0.10 |

| Not married | 99(27.1) | 52(52.5) | 44(44.4) | 60(60.6) | 74(74.8) | ||||

| Residency | |||||||||

| Urban | 205(56.2) | 95(46.3) | 0.83 | 86(42.0) | 0.06 | 109(53.2) | 0.04 | 136(66.3) | 0.38 |

| Rural | 160(43.8) | 76(47.5) | 83(51.9) | 102(63.8) | 113(70.6) | ||||

| Monthly income | |||||||||

| <$450 | 297(81.4) | 126(42.4) | 0.01** | 127(42.8) | 0.01** | 162(54.6) | 0.01 | 197(66.3) | 0.11 |

| ≥$450 | 68(18.6) | 45(66.2) | 42(61.8) | 49(72.1) | 52(76.5) | ||||

| Employment status | |||||||||

| Employed | 261(71.5) | 136((53.1) | 0.01** | 120(46.0) | 0.84 | 157(60.2) | 0.15 | 184(70.5) | 0.14 |

| Unemployed | 104(28.5) | 35(33.7) | 49(47.1) | 54(51.9) | 65(62.5) | ||||

| Education level | |||||||||

| College/University and above | 132(36.2) | 83(62.9) | 0.01** | 65(49.2) | 0.40 | 88(66.7) | 0.01 | 110(83.3) | 0.01** |

| Less than College | 233(63.8) | 88(37.8) | 104(44.6) | 123(52.8) | 139(59.7) | ||||

| High school attribute | |||||||||

| Private | 33(10.7) | 27(81.8) | 0.01** | 16(48.5) | 0.74 | 28(84.9) | 0.01** | 28(84.9) | 0.05* |

| Public | 277(89.6) | 117(42.2) | 126(45.5) | 151(54.5) | 189(68.2) | ||||

| Smoking status | |||||||||

| Heavy smoker (≥20/day) | 113(31.0) | 51(45.1) | 0.66 | 51(45.1) | 0.76 | 62(64.9) | 0.45 | 65(57.5) | 0.01** |

| <20 cigarettes/day | 252(69.0) | 120(47.6) | 118(46.8) | 149(59.1) | 184(73.0) | ||||

| Inhale when smoking | |||||||||

| Yes | 190(56.4) | 99(52.1) | 0.01 | 103(54.2) | 0.01 | 121(63.7) | 0.01 | 136(71.6) | 0.14 |

| No | 147(43.6) | 56(38.1) | 59(40.1) | 73(49.7) | 94(64.0) | ||||

| * p<0.05 ** p<0.005 Abbreviations: NRT: Nicotine Replacement Therapy |

|||||||||

Table 2: Characteristics of Beliefs in Different Smoking Cessation Interventions among Chinese Adult Smokers.

Logistic regression results

Univariate (unadjusted OR) and multivariate logistic regression (adjusted OR) results with the beliefs regarding the effectiveness of each intervention category are presented in Table 3 and Table 4.

| Participant Characteristics | NRT Products | Cessation Medications | ||

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) |

Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

Unadjusted OR (95% CI) |

Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | Reference | Reference | ||

| Female | 0.80(0.39-1.62) | 1.03 (0.51-2.08) | ||

| Age | ||||

| 18-40 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |

| ≥40 | 0.44(0.28-0.70) | 0.73(0.47-1.13) | 0.42(0.22-0.79) | |

| Monthly income | ||||

| <$450 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| ≥$450 | 2.66(1.53-4.61) | 2.80(1.32-5.92) | 2.16(1.26-3.71) | 2.53(1.28-5.00) |

| Education | ||||

| Below | Reference | Reference | Reference | |

| College and above | 2.79(1.80-4.34) | 2.24(1.21-4.14) | 1.20(0.78-1.85) | |

| High school type | ||||

| Public | Reference | Reference | Reference | |

| Private | 6.15(2.46-15.38) | 6.79(1.89-24.43) | 1.13(0.55-2.32) | |

| Inhale when smoking | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | |

| Yes | 1.77(1.14-2.74) | 1.95(1.07-3.54) | 1.77(1.14-2.73) | |

Insignificant results are not shown

Table 3: Univariate and Multivariate Logistic Regression Results of Predictors of Beliefs in Effectiveness of Different Interventions among Chinese.

| Participant Characteristics | Pharmacologic Methods | Behavioral Methods | ||

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) |

Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

Unadjusted OR (95% CI) |

Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | Reference | Reference | ||

| Female | 0.71(0.35-1.43) | 0.81(0.39-1.69) | ||

| Age | ||||

| <40 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| ≥40 | 0.56(0.36-0.87) | 0.36(0.19-0.71) | 0.47(0.30-0.75) | 0.36(0.18-0.72) |

| Residence | ||||

| Rural | Reference | Reference | Reference | |

| Urban | 0.65(0.42-0.99) | 0.49(0.26-0.93) | 0.82(0.52-1.28) | |

| Monthly income | ||||

| <$450 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |

| ≥$450 | 2.15(1.21-3.83) | 3.05(1.38-6.72) | 1.65(0.90-3.04) | |

| Education | ||||

| Below | Reference | Reference | Reference | |

| College and above | 1.79(1.15-2.79) | 3.38(2.00-5.73) | 3.58(1.67-7.66) | |

| High school type | ||||

| Public | Reference | Reference | Reference | |

| Private | 4.67(1.75-12.46) | 4.87(1.06-22.39) | 2.61(1.00-6.98) | |

| Heavy smoker | ||||

| <20/day | Reference | Reference | Reference | |

| ≥20/day | 0.84(0.54-1.31) | 0.50(0.31-0.80) | 0.36(0.18-0.71) | |

| Inhale when smoking | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | |

| Yes | 1.78(1.15-2.76) | 1.95(1.07-3.57) | 1.42(0.90-2.25) | |

| Abbreviations: NRT: Nicotine Replacement Therapy; OR: Odds Ratio; CI: Confident Interval Insignificant results are not shown |

||||

Table 4: Univariate and Multivariate Logistic Regression Results of Predictors of Beliefs in Effectiveness of Different Interventions among Chinese Adult Smokers.

In Table 3, the results showed that in China, smokers aged above 40 years were less likely to believe in the effectiveness of cessation medications (OR: 0.42, 95% CI: 0.22-0.79) as compared with those aged between 18 and 40 years. Smokers with monthly income of $450 and more, were more likely to believe in the effectiveness of NRT products (OR: 2.80, 95% CI: 1.32-5.92) as compared with those with monthly income less than $450. Smokers with an education level of college or more, (OR: 2.24, 95% CI: 1.21-4.14) were more likely to believe in the effectiveness of NRT products than those who had an education level of high school or less. Smokers who studied in private school were more likely to hold the beliefs regarding the effectiveness of NRT products (OR: 6.79, 95% CI: 1.89-24.43) than those who studied in public school. Smokers who preferred to inhale while smoking were more likely to believe the effectiveness of NRT products (OR: 1.95, 95% CI: 1.07-3.54) than those who did not inhale while they smoked.

In Table 4, the results showed that in China, smokers aged above 40 years were less likely to believe in the effectiveness of pharmacologic methods (OR: 0.36, 95% CI: 0.19-0.71), and behavioral methods (OR: 0.36, 95% CI: 0.18-0.72), as compared with those aged between 18 and 40 years. Smokers who reside in urban area were less likely to believe in the effectiveness of pharmacologic methods (OR: 0.49, 95% CI: 0.26-0.93) than those who reside in rural area. Smokers with monthly income of $450 and more, were more likely to believe in the effectiveness of pharmacologic methods (OR: 3.05, 95% CI: 1.38-6.72) as compared with those with monthly income less than $450. Smokers with an education level of college or more were more likely to believe in the effectiveness of behavioral interventions (OR: 3.58, 95% CI: 1.67- 7.66) than those who had an education level of high school or less. Smokers who studied in private school were more likely to hold the beliefs regarding the effectiveness of pharmacologic interventions (OR: 4.87, 95% CI: 1.06-22.39) than those who studied in public school. Smokers who smoke more than 20 cigarettes per day were less likely to believe the effectiveness of behavioral methods (OR: 0.36, 95% CI: 0.18- 0.71) than those who smoke less than 20 cigarettes per day. Smokers who preferred to inhale while smoking were more likely to believe the effectiveness of pharmacologic methods (OR: 1.95, 95% CI: 1.07-3.57) than those who did not inhale while they smoked.

Discussion

In our study, we found that nearly half of respondents believed in the effectiveness of NRT products, cessation medications, nicotine gum or lozenge, and TV or radio program against smoking, while about 30% of respondents believed in the effectiveness of nicotine patch and nicotine inhaler or nasal spray only. More than half of the smokers believed that discussions with health care providers would be effective, followed by educational program.

Smokers with higher socioeconomic status in terms of higher education level, being employed, higher monthly income, smokers aged above 40 years were more likely to believe the effectiveness of smoking cessation interventions (both pharmacologic and behavioral interventions). Smokers that reside in rural areas, who had higher addiction level, were more likely to believe in the effectiveness of pharmacologic methods were more likely to believe in effectiveness of pharmacologic methods than those who reside in urban areas, and who had lower addiction level, respectively. Heavy smokers (≥20 cigarettes per day) were found less likely to believe the effectiveness of behavioral methods than smokers smoking less than 20 cigarettes per day.

Findings of the study show that smokers with higher socioeconomic status (higher education level, being employed, higher monthly income) were more likely to believe the effectiveness of smoking cessation interventions (both pharmacologic and behavioral interventions). Among the smokers in our sample, those who were employed and had higher income ($450 and more vs. less than $450) were more likely to believe the effectiveness of pharmacologic methods than those who were not employed and had lower income. This might be explained by economic factors, as affordability can play a role in the smokers’ judgment regarding the effectiveness of cessation interventions. Their beliefs in effectiveness might be offset by the cost of the interventions. This finding is consistent with the study by Lee et al. [30] where affordability affected smokers with lower socioeconomic status to become reluctant to use pharmacologic interventions.

Higher education level (college degree or more) of smoker was another predictor of believing in effectiveness of interventions in this study. Likewise, private high schools nomally provide better education, therefore, smokers who graduated from private schools had better education and were more likely to believe in those formal cessation interventions. A study conducted in four countries, Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States, also found that better educated smokers were more likely to use pharmacologic methods [31]. It might be because they were more likely to be aware of the effectiveness of those advanced cessation interventions including NRT products and behavioral intervetions, and thereby have more favourable beliefs regarding effectiveness of these interventions. From a public health perspective, reporting success rates for various interventions may increase a smoker’s belief in the effectiveness of the interventions.

We found that smokers aged above 40 years were less likely to believe pharmacologic and behavioral methods than those aged between 18 and 40 years in China. This might be because older people in China were less likely to accept the new concept of smoking cessation interventions and might be opposed to the idea of taking medications when no illness was diagosed. This finding is consistent with the results from previous studies that higher age of the smokers showed lower intention to quit smoking using any intervention [32,33].

We found that respondents that reside in urban areas were less likely to believe in the effectiveness of pharmacologic methods than those residing in rural areas, which was unexpected. This might be reflective of the social behavior of smoking in urban areas, or concerns about the adverse effect of cessation medications, because of the traditional prejudice against all chemical drugs due to perceived toxicity.

In this study, heavy smokers (≥20 cigarettes per day) were found less likely to believe the effectiveness of behavioral methods than smokers smoking less than 20 cigarettes per day. (24]. Therefore, the intensity and effectiveness of the behavioral interventions are always likely to be quesitioned by Chinese smokers. Similarly, advice from health professionals played limited role in promoting an attempt to quit [24,34]. Hence, demonstrating the effectiveness of behavioral interventions by reporting successful quitting among smokers who used behaviral interventions can be influential in China.

Smokers who had higher addiction level, defined as inhale when smoking, as previously reported [35], were more likely to believe in effectiveness of pharmacologic methods than those who had lower addiction level. This finding suggests that smokers with high addiction level might believe that they may need aids such as a medication to relieve the withdral symptoms associated with quitting as they feel dependent on the cigarette. Further research is needed to identify specific medications that could be benficial among Chinese smokers.

This study has some limitations. First, the study was conducted using convenience sampling, thus, we are not able to describe nonparticipants. Generalizability might be limited to similar subpopulations as the surveys were collected from only two sites in China, but participants were randomly picked during the time the survey was administered. There were some missing values for some participants. We removed partially completed surveys to minimize inconsistency and bias due to missing value. Information bias may be generated when the survey was administered. Translation back-translation method was conducted before distribution of the survey, to decrease information bias.

Despite these limitations, this is the first study to identify factors associated with Chinese smokers’ beliefs regarding effectiveness of various available cessation interventions. To increase the utilization of the cessation interventions, smokers’ beliefs should be considered. Increasing accessibility of pharmacological interventions can be directly beneficial, to smokers with younger age, higher education, higher income, higher addiction and who reside in rural area. While behavioral interventions can be mostly beneficial to smokers with younger age, higher education and light smokers. Our findings suggest the urgent need to: (1) increase awareness of the effectiveness of pharmacologic and behavioral methods by healthcare provider, government and mass media; (2) encourage the utilization of pharmacologic and behavioral methods; (3) provide resources and access for obtaining smoking cessation assistance; (4) additional efforts are needed among smokers of older age, low educational level, low income, high level of addiction, and heavy smoking.

Conclusion

The rates of believing in the effectiveness of available smoking cessation interventions among Chinese adult smokers ranged from approximately 30% to 60%. The utilization of formal cessation interventions including both pharmacologic and behavior methods can be limited by smokers’ beliefs which should be considered in choosing a smoking cessation intervention.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Ronald J. Peters for his permission to use the self-report survey.

References

- Papadakis S, McDonald P, Mullen KA, Reid R, Skulsky K, et al. (2010) Strategies to increase the delivery of smoking cessation treatments in primary care settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med 51: 199-213.

- WHO (2008) The Global Burden of Disease 2004 Update. WHO Press, World Health Organization, Switzerland.

- Wynder EL, Graham EA (1985) Landmark article May 27, 1950: Tobacco Smoking as a possible etiologic factor in bronchiogenic carcinoma. A study of six hundred and eighty-four proved cases. JAMA 253: 2986-2994.

- Wynder EL, Stellman SD (1977) Comparative epidemiology of tobacco-related cancers. Cancer Res 37: 4608-4622.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2009) State-specific secondhand smoke exposure and current cigarette smoking among adults - United States, 2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 58: 1232-1235.

- Walser T, Cui X, Yanagawa J, Lee JM, Heinrich E, et al. (2008) Smoking and lung cancer: the role of inflammation. Proc Am Thorac Soc 5: 811-815.

- Dennish GW, Castell DO (1971) Inhibitory effect of smoking on the lower esophageal sphincter. N Engl J Med 284: 1136-1137.

- Van Hemelrijck MJ, Michaud DS, Connolly GN, Kabir Z (2009) Tobacco use and bladder cancer patterns in three western European countries. J Public Health (Oxf) 31: 335-344.

- Fuchs CS, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Giovannucci EL, Hunter DJ, et al. (1996) A prospective study of cigarette smoking and the risk of pancreatic cancer. Arch Intern Med 156: 2255-2260.

- Bronnum-Hansen H, Juel K (2001) Abstention from smoking extends life and compresses morbidity: a population based study of health expectancy among smokers and never smokers in Denmark. Tob Control 10: 273-278.

- Gu D, Kelly TN, Wu X, Chen J, Samet JM, et al. (2009) Mortality attributable to smoking in China. N Engl J Med 360: 150-159.

- WHO (2007) WHO Tobacco Fact sheet: World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific. World Health Organization.

- Sarna L, Cooley ME, Danao L (2003) The global epidemic of tobacco and cancer. Semin Oncol Nurs 19: 233-243.

- Sung HY, Wang L, Jin S, Hu TW, Jiang Y (2006) Economic burden of smoking in China, 2000. Tob Control 15 Suppl 1: i5-i11.

- Judith M, Michael E (2002) The Tobacco Atlas. World Health Organization.

- Schuck K, Otten R, Engels RC, Kleinjan M (2011) The relative role of nicotine dependence and smoking-related cognitions in adolescents' process of smoking cessation. Psychol Health 26: 1310-1326.

- Marlow SP, Stoller JK (2003) Smoking cessation. Respir Care 48: 1238-1254.

- Liu J (2010) A revolutionary approach for the cessation of smoking. Sci China Life Sci 53: 631-632.

- Murthy P, Subodh BN (2010) Current developments in behavioral interventions for tobacco cessation. Curr Opin Psychiatry 23: 151-156.

- Rosen LJ, Ben Noach M (2010) Systematic reviews on tobacco control from Cochrane and the Community Guide: different methods, similar findings. J Clin Epidemiol 63: 596-606.

- Stead LF, Bergson G, Lancaster T (2008) Physician advice for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD000165.

- Yang J, Hammond D, Driezen P, O'Connor RJ, Li Q, et al. (2011) The use of cessation assistance among smokers from China: Findings from the ITC China Survey. BMC Public Health 11: 75.

- Yu DK, Wu KK, Abdullah AS, Chai SC, Chai SB, et al. (2004) Smoking cessation among Hong Kong Chinese smokers attending hospital as outpatients: impact of doctors' advice, successful quitting and intention to quit. Asia Pac J Public Health 16: 115-120.

- Vogt F, Hall S, Marteau TM (2008) Understanding why smokers do not want to use nicotine dependence medications to stop smoking: qualitative and quantitative studies. Nicotine Tob Res 10: 1405-1413.

- Everson-Hock ES, Taylor AH, Ussher M (2010) Readiness to use physical activity as a smoking cessation aid: a multiple behaviour change application of the Transtheoretical Model among quitters attending Stop Smoking Clinics. Patient Educ Couns 79: 156-159.

- Schifter DE, Ajzen I (1985) Intention, perceived control, and weight loss: An application of the theory of planned behavior. J Pers Soc Psychol 49: 843-851.

- Peters RJ Jr, Kelder SH, Prokhorov A, Amos C, Yacoubian GS Jr, et al. (2005) The relationship between perceived youth exposure to anti-smoking advertisements: how perceptions differ by race. J Drug Educ 35: 47-58.

- Peters RJ, Kelder SH, Prokhorov A, Springer AE, Yacoubian GS, et al. (2006) The relationship between perceived exposure to promotional smoking messages and smoking status among high school students. Am J Addict 15: 387-391.

- Westmaas JL, Abroms L, Bontemps-Jones J, Bauer JE, Bade J (2011) Using the internet to understand smokers' treatment preferences: informing strategies to increase demand. J Med Internet Res 13: e58.

- Fix BV, Hyland A, Rivard C, McNeill A, Fong GT, et al. (2011) Usage patterns of stop smoking medications in Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States: findings from the 2006-2008 International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health 8: 222-233.

- Lillard DR, Plassmann V, Kenkel D, Mathios A (2007) Who kicks the habit and how they do it: socioeconomic differences across methods of quitting smoking in the USA. Soc Sci Med 64: 2504-2519.

- Djikanovic B, Marinkovic J, Jankovic J, Vujanac V, Simic S (2010) Gender differences in smoking experience and cessation: do wealth and education matter equally for women and men in Serbia? J Public Health (Oxf) 33: 31-38.

- Abdullah AS, Ho LM, Kwan YH, Cheung WL, McGhee SM, et al. (2006) Promoting smoking cessation among the elderly: what are the predictors of intention to quit and successful quitting? J Aging Health 18: 552-564.

- Hoffmann D, Melikian AA, Wynder EL (1996) Scientific challenges in environmental carcinogenesis. Prev Med 25: 14-22.

Citation: Yu Y, Yang M, Sansgiry SS, Essien EJ, Abughosh S (2011) Beliefs in Effectiveness of Various Smoking Cessation Interventions among Chinese Adult Smokers. Epidemiol 1:106. DOI: 10.4172/2161-1165.1000106

Copyright: © 2011 Yu Y, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 14365

- [From(publication date): 11-2011 - Sep 22, 2024]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 9949

- PDF downloads: 4416