A Prognostic Model To Predict the Risk of Cesarean Delivery after Induction of Labour; Development, Validation and Clinical Utility

Received: 28-May-2024 / Manuscript No. JPCH-24-137436 / Editor assigned: 31-May-2024 / PreQC No. JPCH-24-137436 (PQ) / Reviewed: 15-Jun-2024 / QC No. JPCH-24-137436 / Revised: 03-Jun-2024 / Manuscript No. JPCH-24-137436 (R) / Published Date: 10-Jun-2025

Abstract

Background: Induction of Labour (IoL) is an increasingly used obstetric procedure and cesarean delivery is regarded as a major complication. Evaluating the risk of cesarean delivery after IoL is crucial in making informed decisions between labor induction and pre-labor cesarean delivery. Therefore, this study aims to develop and validate a risk prediction model for Cesarean Section (CS) after IoL and evaluate its clinical utility.

Methods: A prospective cohort study was conducted at the University of Gondar Specialized and Tertiary Hospital, Ethiopia, involving 612 pregnant women with an indication for IoL. Univariable and multivariable analyses were used to select predictors and model selection was based on the loglikelihood ratio test and Bayesian information criterion. Model accuracy was evaluated by the area under the receiver operating characteristics curve (AUC) and a calibration plot. Internal validation was performed using bootstrapping and clinical utility was evaluated using decision curve analysis. A simplified risk score and web calculator were developed for practical use.

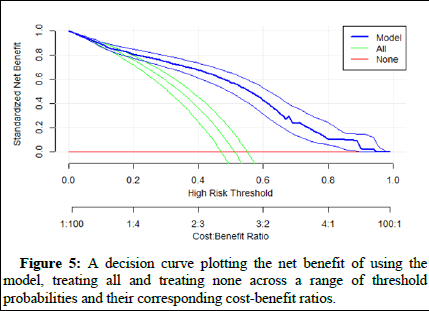

Results: The incidence of CS among women who underwent IoL was 51%. The final risk prediction model included three predictors: Parity, history of stillbirth and Bishop score. The model exhibited good discrimination (AUC: 0.82 (95% CI: 0.79 to 0.87) and calibration. After internal validation the model had a similar performance (AUC: 0.82) to the original model, indicating low chances of overfitting. The decision curve analysis demonstrated the higher net benefit of treatment decisions guided by the model across the range of threshold probabilities.

Conclusion: The risk prediction model based on parity, history of stillbirth and Bishop score, demonstrated good discrimination, calibration and clinical utility in stratifying women with an indication for IoL according to their risk of CS. This model has the potential to guide clinicians in making informed decisions regarding IoL and pre-labour CS, thereby improving labour outcomes.

Keywords: Cesarean delivery; Induction of labour; Risk prediction; Prognostic model

Abbreviation

95% CI: 95% Confidence Interval; AOR: Adjusted Odds Ratio; ANC: Antenatal Care; APH: Antepartum Hemorrage; AUC: Area Under the Curve; BIC: Bayesian Information Criterion; BMI: Body Mass Index; CS: Cesearan Section; GDM: Gestaional Diabetes Millitus; HDP: Hypertensive Disorders in Pregnancy; IoL: Induction of Labour; IQR: Interquartile Range; IUGR: Intrauterine Growth Restriction; LMIC: Low and Middle Income Countries; LNMP: Last Normal Menstural Period; LR+: Postive Liklihood Ratio; LR-: Negative Liklihood Ratio; LRT: Liklhood Ratio Test; NPV: Negative Predictive Value; NS: Normal Saline; PPV: Positive Predictive Value; PROM: Premature Rapture of Membrane; RL: Ringer Lactate; ROC: Receiver Operating Characteristics; SD: Standard Deviation; SVD: Spontaneous Vaginal Delivery; UGSTH: University of Gondar Specialized and Tertiary Hospital; US: United States; VIF: Variable Inflation Factor; WHO: World Health Organization

Introduction

Induction of Labour (IoL) is a process of artificially stimulating the uterus to initiate labour that enables women to deliver expeditiously when the natural onset of labour is unlikely or risky. IoL is indicated for various obstetric, medical and fetal conditions including post-term pregnancy, Pre-labour Rupture of the Membrane (PROM), chorioamnionitis, Intrauterine Fetal Growth Restriction (IUGR), oligohydramnios, Gestational Diabetes Millets (GDM) and Hypertensive Disorder of Pregnancy (HDP) [1]

The decision between IoL and pre-labor Cesarean Section (CS) involves evaluating the potential risk of CS following an attempted vaginal delivery. However, there has been a significant increase in the number of women undergoing IoL in recent decades irrespective of their risk for emergency CS. In the United States (US), the rate of IoL rose from 9.6% in 1990 to 27.1% in 2018. Similar trends have been observed in other developed countries, with induction involved in one in every four to ten deliveries. In developing countries like Ethiopia, IoL is also becoming a common obstetric procedure [2].

IoL is recognized as a significant contributor to the escalating incidence of CS worldwide, surpassing the World Health Organization’s (WHO) recommended rate of 5%-15% of all deliveries in 2009. Multiple factors can increase the risk of CS after IoL, including maternal age, obesity, cervical status, parity, gestational age and medical conditions like diabetes and hypertension. CS following IoL imposes a dual burden on women, subjecting them to prolonged labor only to end up with a CS, a procedure that may introduce additional complications [3-5].

Beyond the significant health impact, undergoing CS following IoL has a substantial financial burden. According to a recent study conducted in Spain, the average total cost of IoL and CS following IoL was € 3589.87 and € 4830.45, respectively. These costs are significantly higher than the cost of Spontaneous Vaginal Delivery (SVD), which is € 3037.45. Given these implications, it would be both clinically and economically advantageous to be able to predict the likelihood of CS following IoL induction among women with an indication for this procedure.

Even though some studies have been conducted to predict the risk of CS following IoL, their applicability in diverse contexts is limited due to various factors. These studies have consistently been conducted in developed countries, recruited specific women population, and used variables that are not routinely collected in standard care. This makes it difficult to implement the models in resource-limited settings and for heterogeneous women populations with different indications of IoL.

Therefore, this study aimed to develop and validate a prognostic model for predicting CS and evaluate its clinical utility among women with an indication of IoL in low and middle-income countries. The model used variables that can be obtained from routine obstetric history and physical examination before conducting the procedure, making it a practical tool for clinical decision-making. Through calculating the risk of CS, the model could prevent subsequent CS after IoL and help consider alternative intervention like pre-labour CS. Furthermore, it will promote women-centered care by facilitating informed decision-making about IoL [6-8].

Materials and Methods

Study design and period

This study applied a prospective cohort study design to investigate predictors of CS following IoL between October 10th, 2021 and March 2023.

Study setting: The study was conducted at the University of Gondar Specialized and Tertiary Hospital (UGSTH) located in the Amhara region, Ethiopia. The hospital is one of the biggest hospitals in the region and provides service for more than 5 million populations in the catchment area. On average 5-8 women deliver daily in the hospital, where about 25% of all deliveries require IoL. The rate of CS is also reported to be high in the hospital. IoL at UGSTH is carried out in accordance with the national induction protocol, where women are administered with 5 IU of oxytocin added to either Normal Saline (NS) or Ringer Lactate (RL) solution. Having previous CS scar is an absolute contraindication for IoL in UGSTH.

Population and data collection: All women who have undergone IoL between October 10th, 2021, and March 2023 were the study population and enrolled in this study.

Data were collected by three midwives working in the labour unit. Medical characteristics were extracted from the medical records that were validated by interviewing the women and physical examination. Variables related to the procedure like membrane status, type of induction and indication of induction was recorded from the patient assessment sheet. A physical examination was considered if the information about the variables is not available. The time when the procedure is initiated was recorded, all complications that occurred throughout the procedure were collected, and the mode of delivery was indicated in the data collection form [9,10].

Variables of the study: The outcome of the study was CS following IoL. Predictors such as maternal age, Body Mass Index (BMI), gestational age, gravidity, parity, history of abortion, history of stillbirth, history of neonatal morality, ANC visit, history of antepartum complications, type of induction, Bishop score, indication for induction, membrane status, cervical ripening, fetal sex and birth weight were included in the prediction model.

The age and previous obstetric history of the women was obtained from their medical record, which was validated by asking the participants. The number of previous pregnancies was counted and categorized into primigravida (if the current pregnancy is her first) and multigravida (for women who have more than one pregnancy). The number of prior births was also counted and women were categorized into nulliparous (women who have never given birth) and parous (women who have given birth previously).

To obtain the indication for IoL, the medical, obstetric, or fetal complication that was the main reason to consider the procedure was recorded. History of antepartum complications was measured by taking the occurrence of complications in the current pregnancy such as GDM, hyperemesis gravidarum, iron deficiency anemia and others. If the woman had one of the listed complications it was recorded as “Yes” and “No” otherwise. The gestational age was calculated from the date of early ultrasound/Last Menstrual Period (LNMP) and categorized into pre-term (<37 weeks), term (37-40 weeks) and postterm (>40 weeks). History of abortion (yes, no), history of stillbirth (yes, no), antenatal care (ANC) visit (yes, no), fetal sex (female, male), height and weight were also collected and coded accordingly. The BMI was then calculated from the height and weight measure.

The type of induction was categorized into emergency (if the procedure is considered for an emergency case) and elective (if it was previously planned). The Bishop score was calculated from cervical effacement, fetal station, position, cervical consistency and cervical dilation. It ranges from 0 to 13 and was categorized into “favorable” (score greater or equal to six) and “unfavorable” (if the value is less than six). The status of the membrane was examined and recorded as “intact” if it was not ruptured at the start of the procedure and “ruptured” otherwise. Cervical ripening was also measured by physical examination and coded as “Yes” if ripened and “No”

Data processing and analysis: R statistical programming language version 4.3.2 was used for data cleaning, processing and analysis. The proportion of missing values was calculated both for the outcome and all predictors. The missingness pattern was investigated using correlation analysis and Little’s Missing Completely At Random (MCAR) test. Multiple imputation was considered if the assumption of MCAR doesn’t hold [11,12].

The outcome variable was coded as “Yes” if the women had CS and “No” otherwise. Descriptive statistics, including mean and Standard Deviations (SD), median and Inter-Quartile Range (IQR), percentages and rates were carried out. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used for continuous variables to test for the normal distribution and choose the appropriate measure of central tendency and dispersion. The number of women with CS (event) was divided by the total number of women undergone IoL during the study period (population at risk) to obtain the incidence of cesarean delivery.

Model development and validation: To select predictors the univariable model was compared with the null model using the Log Likelihood Ratio test (LLR). A p-value of 0.15 was applied to identify the candidate variable for the multivariable regression model. The Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) was used for backward and stepwise model reduction to select the final model and the model with the lowest BIC value was selected. Multicollinearity between the included variables was tested using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). In the multivariable model, a p-value corresponding to the 5% significance level was used to determine an association. The Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) with 95% CI was calculated.

The model’s accuracy i.e., its discrimination was evaluated using area under the Receiver Operating Characteristics (ROC) curve (AUC) and its calibration using the calibration plot and the Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test [13].

The model was internally validated using a bootstrapping technique that estimates how well the prediction model developed in the development set (original dataset) would perform on a hypothetical set of new subjects. We created 1000 datasets by constructing a random sample of women “with replacement” from the original dataset. The model performance was calculated for each bootstrap sample and the mean value was compared with the original model. The overoptimism coefficient was also computed to estimate the degree of overfitting.

Risk score calculation: For practical utility, a simplified risk score was generated from the prediction model. The regression coefficient of each predictor variable in the final model was dived by the smallest coefficient and rounded to the nearest integer. For each score, the proportion of women and the risk of CS were calculated. A regressionbased model was also built using the simplified risk score and the model accuracy measures were evaluated. To obtain the optimal cutoff value of the predicted risk and risk score the “Youden” index was used. The performance of each risk score was compared using their corresponding sensitivity, specificity, Positive Predictive Value (PPV), Negative Predictive Value (NPV), positive (LR+) and negative Likelihood Ratio (LR-). A nomogram was also to make ease of calculate the risk score.

Moreover, a web-calculator was developed using the shiny package in R to input data and receive a risk estimate in real-time with a more user-friendly and intuitive way.

Decision curve analysis: Decision curve analysis was used to assess the clinical utility of the model in identifying women who have high risk of CS following IoL. The analysis incorporates the consequence of each decision by considering the relative weight of false positive and false negative cases (w). It estimates the net benefit of the model across a range of threshold probabilities, which represent the probabilities of CS above which treating with an alternative intervention than IoL is considered superior. In the analysis 10,000 bootstrap samples were used to reduce bias and provide a more accurate estimate of the net benefit of the predictive model. The cost benefit ratio was then compared between our model and the default strategies such as treating all and treating none [14].

The reporting of this study adheres to the Transparent Reporting of a Multivariable Prediction Model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis (TRIPOD) statement.

Results

Participant characteristics

A total of 628 women were enrolled in the study. There was missing information for variables such as weight (0.16%), height (0.5%), parity (0.16%), gravidity (0.16%) and gestational age (1.8%) with the overall missing of 0.1%. No missing values were recorded for the outcome variable. Little’s test for MCAR indicated no evidence of non-random missing pattern with p-value of 0.43. There was also no marked difference in the baseline characteristics of participants with and without missing information (Table 1 and S2). Therefore, a complete case analysis was performed with 612 women [15,16].

The median (IQR) age and BMI of women was 27 (6) and 26.9 (3.3) kg/m2 , respectively. The median gestational age of women was 40 weeks with a minimum of 30 and maximum of 43 completed weeks.

Hypertensive disorder during pregnancy was an indication of induction for nearly one-third of the women and 75% (464) of the procedure was electively done. A significant proportion of the women (78%) had their membranes intact at the start of the procedure. The Bishop score was unfavorable in 60.9% of the women and at least one antepartum complication was recorded in 76.3% of the women (Table 1).

Incidence of cesarean section after IoL

Following IoL, 313 (51%) of the women had a cesarean delivery while 299 (49%) of the women delivered vaginally (Table 1).

| Variables | Outcome of induction | ||

| Cesarean-section (n=313) | Vaginal delivery (n=299) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Age | --- | --- | 0.99 (0.96-1.02) |

| BMI | --- | --- | 1.05 (0.99-1.11) |

| History of abortion | |||

| Yes | 46 (14.7%) | 40 (13.4%) | 1.12 (0.71-1.77) |

| No | 267 (85.3%) | 259 (86.6%) | Ref |

| History of stillbirth | |||

| Yes | 39 (12.5%) | 11 (3.7%) | 3.73 (1.93-7.78) |

| No | 274 (87.5%) | 288 (96.3%) | Ref |

| History of neonatal mortality | |||

| Yes | 26 (8.3%) | 26 (8.7%) | 0.95 (0.54-1.68) |

| No | 287 (91.7%) | 273 (91.3%) | Ref |

| ANC visit | |||

| Yes | 297 (95%) | 282 (94.3%) | 1.12 (0.55-2.28) |

| No | 16 (5%) | 17 (5.7%) | Ref |

| History of antepartum complication | |||

| Yes | 233 (74.4%) | 236 (79%) | 0.78 (0.53-1.13) |

| No | 80 (25.6%) | 63 (21%) | Ref |

| Parity | |||

| Nulliparous | 113 (36.1%) | 68 (22.7%) | 1.92 (1.35-2.75) |

| Parous | 200 (63.9%) | 231 (77.3%) | Ref |

| Gravidity | |||

| Primigravida | 173 (55.3%) | 127 (42.4%) | 1.67 (1.22-2.31) |

| Multigravida | 140 (44.7%) | 172 (57.5%) | Ref |

| Gestational age | |||

| Preterm | 6 (1.9%) | 9 (3%) | 0.57 (0.19-1.61) |

| Term | 291 (93%) | 250 (83.6%) | Ref |

| Post-term | 16 (5.1%) | 40 (13.4) | 0.34(0.18-0.62) |

| Bishop score | |||

| <6 | 277 (84.5%) | 95 (31.8%) | 16.5 (10.9-25.6) |

| ≥ 6 | 36 (11.5%) | 204 (68.2%) | Ref |

| Type of induction | |||

| Elective | 238 (76.1%) | 226 (76.6%) | 1.03 (0.71-1.48) |

| Emergency | 75 (23.9%) | 73 (23.4%) | Ref |

| Cervical ripening | |||

| Yes | 200 (63.9%) | 197 (65.9%) | 0.92 (0.66-1.28) |

| No | 113 (36.1%) | 102 (34.1%) | Ref |

| Membrane status | |||

| Ruptured | 75 (24%) | 57 (19.1%) | Ref |

| Intact | 238 (76%) | 242 (80.9%) | 0.75 (0.51-1.10) |

| Infant sex | |||

| Female | 197 (62.9%) | 187 (62.5%) | Ref |

| Male | 116 (37.1%) | 112 (37.5%) | 0.98 (0.71-1.36) |

| Birth weight (g) | - | - | 1.03 (0.91-1.25) |

| Indication for induction | |||

| APH | 9 (2.9%) | 14 (4.7%) | Ref |

| GDM | 33 (10.5%) | 15 (5%) | 3.42 (1.24-9.97) |

| HDP | 100 (32%) | 83 (27.8%) | 1.87 (0.78-4.51) |

| IUGR | 42 (13.4%) | 17 (5.7%) | 3.84 (1.42-10.9) |

| Oligohydramnios | 38 (12.1%) | 74 (24.7%) | 0.80 (0.32-2.07) |

| Post-term | 22 (7%) | 40 (13.4%) | 0.86 (0.32-2.35) |

| PROM | 69 (22%) | 56 (18.7%) | 1.92 (0.78-4.91) |

Table 1: Baseline demographic, obstetric and clinical characteristics of pregnant women by the outcome of induction at the University of Gondar Hospital, Ethiopia from 10th of October 2021 to March 2023; (n=612).

Univariable and multivariable analysis

Variables such as parity, gravidity, history of stillbirth, gestational age, type of induction, indication for induction, Bishop score and membrane status were fitted in to the multivariable model on their significance in the LLR test (p-value<0.15). The VIF values range from 1.5 to a maximum of 2.3 suggesting negligible multicollinearity.

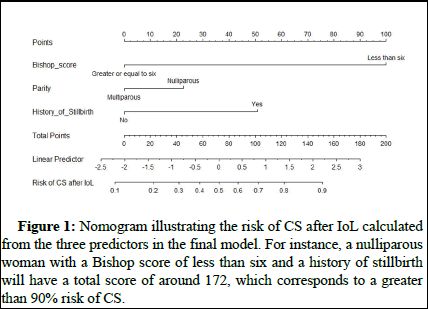

After LLR test, backward and stepwise model reduction the model containing three predictors such as Bishop score, parity and history of stillbirth showed best performance with lowest BIC value (632). The simplified risk scores were calculated in the final reduced model. (Table 2 and Figure 1) [17].

|

Variable |

Multivariable analysis |

P-value |

Simplified risk score |

|

|

AOR (95%CI) |

Regression coefficient |

|||

|

Bishop score |

||||

|

≥ 6 |

Ref |

Ref |

<0.001 |

5 |

|

<6 |

16.1 (10.6-25.2) |

2.78 |

||

|

Parity |

||||

|

Parous |

Ref |

Ref |

0.005 |

1 |

|

Nulliparous |

1.87 (1.21-2.92) |

0.62 |

||

|

History of stillbirth |

||||

|

No |

Ref |

Ref |

<0.001 |

2 |

|

Yes |

4.11 (1.85-9.82) |

1.41 |

||

|

Note: Risk of CS=(5*Bishop score (less than six))+(1*Parity (nulliparous))+(2*History of stillbirth (Yes)) |

||||

Table 2: Multivariable regression coefficients of variables included in the final model with their corresponding simplified risk score.

Figure 1: Nomogram illustrating the risk of CS after IoL calculated from the three predictors in the final model. For instance, a nulliparous woman with a Bishop score of less than six and a history of stillbirth will have a total score of around 172, which corresponds to a greater than 90% risk of CS.

Model performance

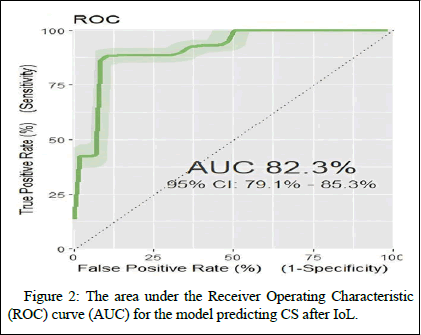

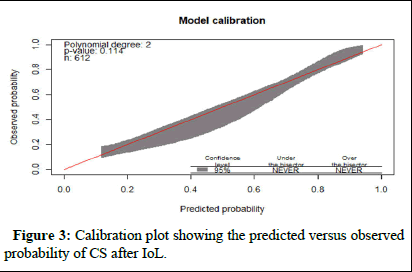

The discrimination capacity (AUC) of the final model was 0.82 (95%CI: 0.79 to 0.85) (Figure 1). The model also showed good calibration ability (Figure 2). The p-value from Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test was 0.95 (Figure 3).

Figure 2: The area under the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC) for the model predicting CS after IoL.

Figure 3: Calibration plot showing the predicted versus observed probability of CS after IoL.

Risk classification using simplified risk score model

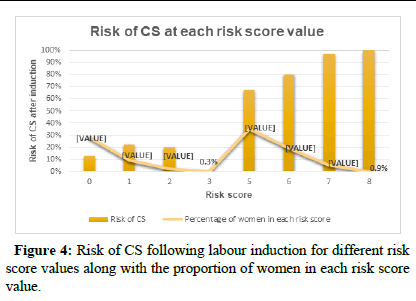

Using the simplified risk model, the calculated risk score ranged from 0 to 8 corresponding to distinct risk of CS between 0 and 100%. The cut-off value for the predicted risk of CS was 0.56. Similarly, the optimal cut-off point for the risk score was five with a sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, LR+, and LR- of 88.5%, 68%, 74.5%, 85%, 2.78 and 0.16, respectively. Detailed information on the risk score performance at different possible cut-off points is available in Table S1 (supplementary materials). The Pearson correlation coefficient between the risk score and incidence of CS was 0.88. The risk of CS corresponding to each risk score is presented in Figure 4 [18].

Figure 4: Risk of CS following labour induction for different risk score values along with the proportion of women in each risk score value.

The simplified risk score model yielded a similar discrimination (AUC=0.82 (95%CI: 0.81 to 0.87) as the original model, with a good calibration ability (p-value of 0.73).

Model validation

The mean AUC value calculated from 1000 bootstrapping samples shows nearly similar performance with the original model (0.82 (95%CI: 0.816-0.828). The over-optimism coefficient was found to be 0.003.

Decision curve analysis

The decision curve analysis showed the importance of using the model to stratify high risk women for alternative intervention over treating all and none of the women. The model has the highest net benefit across the entire range (0 to 1) of threshold probabilities (Figure 5).

Figure 5: A decision curve plotting the net benefit of using the model, treating all and treating none across a range of threshold probabilities and their corresponding cost-benefit ratios.

Discussion

Our study, conducted at a Tertiary Hospital in Ethiopia, revealed a high incidence of CS among women who underwent IoL, with a rate of (51% (95% CI: 47%-55%)). The risk prediction model for CS, using parity, history of stillbirth and Bishop score as predictors, demonstrated good discrimination and calibration. The overoptimism coefficient in the bootstrapping sample was also very low, suggesting the model is not overfitted to the training dataset. The simplified risk score model also showed similar discrimination and calibration to the original model.

A positive correlation was also observed between the simplified risk score and the risk of CS. The selected optimal cut-off points for the risk score and predicted risk showed best performance based on the accuracy measures. These values can be adjusted according to resource availability and clinical decision-making.

The web-calculator developed from the model could provide users with a more user-friendly and intuitive way to input data and receive calculated results in real-time. This enables clinicians to easily access and interacts with the model. However, the model needs to be externally validated before applying the web-calculator into actual clinical practice.

The decision curve analysis depicts higher net benefit of using our model across a range of threshold probabilities above which treating with an alternative intervention than IoL is warranted. However, it is worth noting that the default strategies of treating all or none of the women might not be the most realistic comparisons.

This model showed better performance than the predictive model built by Levine et.al (AUC 0.73 vs. 0.82). The discrepancy in performance could be attributed to the difference in the study population. The latter model recruited women with unfavorable cervix, who may have an elevated risk of unsuccessful IoL regardless of other predictors. Although the performance of our model is similar with the prognostic model developed in US (0.82 95% CI, 0.81-0.83), the latter model recruited only women with term pregnancy, limiting its generalizability. It is also worth noting that our model demonstrated comparable performance using routinely collected variables compared to the US model, which included predictors such as excessive fetal growth and fibroids.

Strength and limitations

This model has several strengths that overcome the limitations of previously developed predictive models. Including all women with different indications for induction, increases the generalizability of our model compared to models that are specific to a certain women population. Additionally, including easily obtainable variables that require less skill and resource to collect makes the model applicable in resource-limited settings.

However, the study is not without limitations. It is important to note that this model was developed under the circumstance where women underwent induction with oxytocin. Considering various induction methods are used in different settings, each with varying potency, the model needs validation for other methods of induction before it can be applied to clinical practice. In addition, women with previous CS scar are not eligible to IoL in the hospital, which limits the model's applicability to this population. Furthermore, important variables, such as gestational weight, were not included in the current prediction model, despite its known impact on the success of IoL and the risk of CS.

Conclusion

This risk prediction model, based on parity, history of stillbirth and Bishop score, provides a valuable tool for clinicians to identify women who are at higher risk of CS after IoL. The model demonstrated good discrimination, calibration, clinical utility and outperforms other prediction models. The model's strength lies in its applicability to resource limited settings and its ease of use with easily obtainable variables. The simplified risk score and web-based calculator developed in the study can also facilitate its implementation.

However, further validation is needed for other methods of induction and women with previous CS scar and the inclusion of additional predictors, such as gestational weight, may improve the model’s performance. Nonetheless, our model has the potential to improve clinical decision making among women with an indication for IoL that may ultimately lead to better maternal and neonatal outcomes in LMICs.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Ethical clearance was obtained from the ethical review board of the University of Gondar; Ref No/IPH/2054/2014. A written informed consent was taken from participants after explaining the purpose of the study.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Availability of Data and Materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

This study has not received any funding.

Author’s Contributions

EGM conceived the study, assisted with data collection, conducted the statistical analysis, drafted the first version of the manuscript and revised the final version. EGM and SC contributed to the study design and the development of the analysis plan. SC provided overall guidance, collaborated in drafting the article, assisted with the statistical analysis, edited and reviewed the final version. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the article.

Acknowledgements

EGM would like to acknowledge the VLIR-UOS ICP program for awarding her a full scholarship and travel grant to visit the study site. The authors would like to acknowledge the study participants and data collectors involved in the study.

References

- Coates D, Homer C, Wilson A, Deady L, Mason E, et al. (2020) Induction of labour indications and timing: A systematic analysis of clinical guidelines. Women Birth 33: 219-230.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Coulm B, Blondel B, Alexander S, Boulvain M, Le Ray C (2016) Elective induction of labour and maternal request: a national population‐based study. BJOG 123: 2191-2197.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- López‐Jiménez N, García‐Sánchez F, Hernández‐Pailos R, Rodrigo‐Álvaro V, Pascual‐Pedreño, et al. (2021) Risk of caesarean delivery in labour induction: A systematic review and external validation of predictive models. BJOG 129: 685-695.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yosef T, Getachew D (2021) Proportion and outcome of induction of labor among mothers who delivered in teaching hospital, Southwest Ethiopia. Front Public Health 9: 686682.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Canavan ME, Brault MA, Tatek D, Burssa D, Teshome A, et al. (2017) Maternal and neonatal services in Ethiopia: Measuring and improving quality. Bull World Health Organ 95: 473-477.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Ventura SJ (2009) Births: Preliminary data for 2007. Natl Vital Stat Rep 57: 1-23.

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kerbage Y, Senat MV, Drumez E, Subtil D, Vayssiere C, et al. (2020) Risk factors for failed induction of labor among pregnant women with Class III obesity. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 99: 637-643.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Demssie EA, Deybasso HA, Tulu TM, Abebe D, Kure MA, et al. (2022) Failed induction of labor and associated factors in Adama hospital medical College, Oromia regional state, Ethiopia. SAGE Open Med 10: 20503121221081009.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Abalos E, Oladapo OT, Chamillard M, Díaz V, Pasquale J, et al. (2018) Duration of spontaneous labour in ‘low-risk’women with ‘normal’perinatal outcomes: A systematic review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 223: 123-132.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Allen VM, O'Connell CM, Farrell SA, Baskett TF (2005) Economic implications of method of delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 193: 192-197.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Simon R, Montañes A, Clemente J, Del Pino MD, Romero MA, et al. (2016) Economic implications of labor induction. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 133: 112-115.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Danilack VA, Hutcheon JA, Triche EW, Dore DD, Muri JH, et al. (2020) Development and validation of a risk prediction model for cesarean delivery after labor induction. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 29: 656-669.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rossi RM, Requarth E, Warshak CR, Dufendach KR, Hall ES, et al. (2020) Risk calculator to predict cesarean delivery among women undergoing induction of labor. Obstet Gynecol 135: 559-568.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Levine LD, Downes KL, Parry S, Elovitz MA, Sammel MD, et al. (2018) A validated calculator to estimate risk of cesarean after an induction of labor with an unfavorable cervix. Am J Obstet Gynecol 218: 254-e1.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vickers AJ, Holland F (2021) Decision curve analysis to evaluate the clinical benefit of prediction models. Spine J 21: 1643-1648.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Collins GS, Reitsma JB, Altman DG, Moons KG (2015) Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD) the TRIPOD statement. Circulation 131: 211-219.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chen W, Xue J, Peprah MK, Wen SW, Walker M, et al. (2016) A systematic review and network meta‐analysis comparing the use of Foley catheters, misoprostol and dinoprostone for cervical ripening in the induction of labour. BJOG 123: 346-354.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ellis JA, Brown CM, Barger B, Carlson NS (2019) Influence of maternal obesity on labor induction: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Midwifery Womens Health 64: 55-67.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Citation: Mekonnen EG, Coenen S (2025) A Prognostic Model to Predict the Risk of Cesarean Delivery after Induction of Labour: Development, Validation and Clinical Utility. J Preg Child Health 12: 698.

Copyright: 2025 Mekonnen EG, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Usage

- Total views: 173

- [From(publication date): 0-0 - Dec 08, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 125

- PDF downloads: 48