Addressing Predictors of Obstetric Violence among Postpartum Women in Public Hospitals of Jimma Zone, Southwest Ethiopia: Call For Action

Received: 02-May-2024 / Manuscript No. JPCH-24-133908 / Editor assigned: 06-May-2024 / PreQC No. JPCH-24-133908 (PQ) / Reviewed: 21-May-2024 / QC No. JPCH-24-133908 / Revised: 03-Jun-2025 / Manuscript No. JPCH-24-133908 (R) / Published Date: 10-Jun-2025

Abstract

Background: Obstetric violence is a serious public health problem that arises from the unprofessional or dehumanized treatment of women by obstetric care providers. This includes verbal abuse, violation of women's autonomy and rights, performing unnecessary or non-consensual care, discrimination against women based on their background, physical abuse, non-dignified care and a lack of privacy and confidentiality during childbirth. It is therefore a complicated issue that impacts women's health and their behavior related to seeking medical attention. Thus, the purpose of this study was to investigate the factors linked to obstetric violence among postpartum women in Jimma public hospitals.

Method: An institutional-based cross-sectional study was conducted among 407 postpartum women in the Jimma zone public hospitals from August 12 to October 12, 2022. A simple random sampling technique was used to select the study subjects for structured, pre-tested face-to-face exit interviews. Data were entered into Epi-Data version 3.1 and exported to SPSS version 23 for analysis. Then, factors that showed significant associations in a simple linear regression model were added to multivariable linear regression models. Variables that had a P-value of <0.05 in the multivariable model were considered statistically significant.

Results: Overall, every woman experienced at least one form of obstetric violence during the labour and childbirth process. On multivariable linear regression analysis, knowledge of the women towards universal rights of childbearing women (β=-0.644, 95% CI=-0.916,-0.372) and the number of ANC contacts (β=-0.135, 95% CI=-0.232,-0.038) were negatively associated with obstetric violence score. In contrast, the unfavorable attitude of health care providers (β=0.600, 95% CI=0.422, 0.777) and intention to deliver at home (β=0.375, 95% CI=0.167, 0.584) are positively associated with increased obstetric violence.

Conclusion: The findings demonstrated that Obstetric Violence (OV) is a complicated phenomenon that can be impacted by several variables, including frequent ANC contacts, the cultural attitudes of healthcare professionals and women's awareness of their universal rights as childbearing women. We urge all parties involved-healthcare professionals, organizations, the community, women and civil society-to take action to address the issues by transforming the culture surrounding obstetric care, advocating for the new WHO ANC model and promoting optimal respectful maternity care, as well as evidence-based practices that follow a right-based framework and educating women about their rights to universal healthcare.

Keywords: Women; Obstetric violence; Predictors; Ethiopia

Introduction

Reducing maternal mortality through institutional birth uptake is a primary goal of the global health community, as is widely known; covering all births in facilities is the intermediate goal. Despite worldwide efforts to promote facility-based deliveries with trained attendants, sub-Saharan Africa still has facility delivery rates of about 50% [1].

Similar to this, the Federal Ministry of Health (EFMOH) of Ethiopia has put in place a complex plan to improve access and facility-based maternal services, but only 48% of births in medical facilities are attended by qualified medical professionals, which is a much lower percentage than in some other SSA countries. For example, the Oromia Region, where this study is being conducted, has a lower institutional delivery service use rate (40.9%) than the other six regions of Ethiopia.

The infrastructure and human resources have been the main targets of interventions over the last 20 years that have attempted to lower maternal mortality and increase facility-based childbirth. Nevertheless, studies indicate that improving maternity health care on its own is ineffective. The reasons why women opt to give birth at home have not received enough attention, despite improvements to the maternal health services and the strengthening of the health system.

Evidence from many countries in sub-Saharan Africa suggests that women may want to give birth there but decide not to do so because they have heard from friends or relatives about inadequate care, poor care or disrespect and abusive care from healthcare professionals in the past. Furthermore, the research findings indicate that a number of African women, including those from Ethiopia, are unable to effectively and efficiently access institutional delivery due to a variety of factors, including staff attitudes, privacy concerns, cultural and traditional norms, abusive language, violation of women’s rights, a lack of compassion and willingness to provide appropriate assistance, patterns of decision-making power within the household and mistreatment [2].

A growing body of research links this hesitation to search for healthcare facilities to abusive and disrespectful provider behaviors during facility-based care for mothers and newborns, as well as obstetric violence. The woman may be deterred from seeking help in the future by her own past experiences. Research indicates that communities and neighbors exchange firsthand obstetric violence experience of healthcare institutions and that a negative experience with one facility can discourage other neighbors from seeking healthcare service.

Obstetric Violence (OV) is a serious public health problem that violates women`s rights. It is when obstetric medical staff treat women in an unprofessional or disrespectful way that consists of verbal abuse, denying women their autonomy/rights, performing unnecessary or non-consenting medical procedures, discriminating against women based background, showing disrespect for the needs and pains of women, physical abuse, invasive practices and a lack of privacy and confidentiality during childbirth. OV can impact the experience of labour and birth and includes situations involving dehumanized care, communication failures, disempowerment, abuse of medicalization and pathogenesis of reproductive physiological processes. Therefore it is a complex problem that affects women's health and can lead to physical harm and psychological problems to both birthing people and their babies [3].

In addition, It can also have an impact on the decision-making process of women to seek care (for example, if they fear that they won't be treated well), as well as the standard of care (for example, if they receive mistreatment or inadequate care). The provision of respectful maternity care is impacted by a number of factors, including physical abuse, non-confidential care, non-consented care, detention, abandonment, physical abuse, sexual abuse, verbal abuse, stigma and discrimination, failure to meet professional standards of care, poor rapport between women and providers and limitations and conditions within the health system. Apart from the potential consequences for skilled delivery attendance at medical facilities, acts of disrespect and abuse also lead to needless suffering for women and constitute basic breaches of their human rights.

Recent data unequivocally revealed that women have been the victims of obstetric violence, mistreatment and abused at healthcare facilities all around the world. As a result, researches from Asian and African nations, including Ethiopia, revealed that the percentage of women who experience obstetric violence varies from 49.4% to 98%. Furthermore, the prevalence of obstetric violence, mistreatment and abusive are not only observed in developing nations but also observed in developed nations like the United States and Canada.

One of the biggest obstacles to improve health care is still training medical professionals to be courteous practitioners. Respect for patients' autonomy, dignity and respect are fundamental human rights that must be included in the treatment that health professionals deliver. As per the UN Human Rights Declaration, every individual is entitled to equal rights and dignity from birth. The rights to equality and privacy are also stated in Ethiopia's constitution's articles 25 and 26.

Many medical personnels in Ethiopia's healthcare system are wellliked by the people they serve since they have dedicated their entire careers to providing public services. But a sizable percentage of medical personnel treat patients and their families like nothing more than "cases," and they lack empathy and respect for them. A number of research carried out in Ethiopia investigate the unethical behaviors health practitioners, including sending hurtful messages, yelling at patients, mistreating, hitting and insulting them. Pregnant women prefer to give birth at home as a result of this mistreatment [4].

According to a 2018 WHO report, interpersonal, facility and health system interventions are necessary to promote respectful maternity care and lessen obstetric violence or mistreatment of women during labor and delivery. Addressing obstetric violence, mistreatment and abuse in facility-based childbirth is crucial for the international community, including Ethiopia, to meet sustainable development goals for skilled care coverage and maternal mortality reduction. Thus, an urgent action is needed to overcome the challenges of disrespect and abuse in facility child birth especially in Ethiopia. Thus, this research attempted to address the factors that contribute to obstetric violence among postpartum women in public hospitals of Southwest Ethiopia [5].

Materials and Methods

Study setting and population

A facility based cross-sectional study was conducted in public hospitals in the Jimma zone from August 12, 2022 (start date) to October 12, 2022 (end date) to recruit study participants. It is one of the zones of Oromia Regional State, which has an estimated total population of more than 3,538,463. Of these, males account for 1,779,834 and females 1, 758, 629. In Jimma zone, there is one university hospital, 6 primary hospitals, 115 health centers and 520 health posts. These hospitals namely include Jimma Medical Center, Shenen Gibe Hospital, Limmu Hospital, Agaro Hospital, Dimitu Hospital, Seka Chokorsa Hospital and Nada Hospital. For this study, Seka Hospital and Agaro Hospital were selected. In both hospitals, different health services including MCH services are provided. Seka hospital is one of the zonal hospitals which are serving more than 2 million populations per year. The hospital is accountable to the Seka Woreda Health Office whereas Agaro hospital is accountable to the Agaro Town Health office. The two hospitals are 60 km away from each other. The monthly ANC, institution delivery and PNC coverage in both study areas is 350, 432 and 456, respectively. The number of staff in Seka hospital and Agaro hospital is 32 and 27, respectively. All postnatal mothers who gave facility-based childbirth at the study hospitals during the study period were part of the study population [6].

Sample size and sampling procedure

The sample size was determined using a single population proportion formula based on the following assumptions: The proportion of mothers who experienced disrespect and abuse in service delivery points of 49.7%, 95% level of confidence level, 0.05 margin of error between the sample and the population and 6% non retrieval rate. Therefore, the final sample size for the study was 407 [7].

Two hospitals (Agaro hospital and Seka hospital) out of six public hospitals in the Jimma zone were selected purposively based on the number of clients they registered in the last year (proportion of women deliveries per year), the type of facility, similarity of health care providers distribution and the socio-demographic characteristics of the community. Jimma University Medical Center and other non-selected hospitals were excluded because of the high turnover of students, distance, COVID-19 issue, low case flow and instability/securityrelated problems. Accordingly; a simple random sampling technique was used to select the study subjects. Health care providers working in the MCH unit have a registration with a list and number of postpartum women who visited the respective hospitals they are working at. Hence, the sampling frame having a list of participants was prepared by the providers together with the data collectors. The enumerators used this sampling frame to select eligible women who meet the inclusion criteria for this study. The data were collected randomly from postnatal women who delivered in the study hospitals until the desired sample size was achieved. All postnatal mothers who have a history of facility childbirth and who gave consent to participate in the study were enrolled into the study, irrespective of their marital status and other background information.

Operational definition

Obstetric violence consists of six domains and 29 items: Nonconfidential care (4 items), non-consented care (4 items), nondignified care (10 items), discrimination care (4 items), detention in the health facilities (2 items) and physical abuse (5). The responses are as follows: Never (0), rarely (1), sometimes (2), frequently (3), always (4). Statements with negative conceptions were scored negatively. High median scores on this scale indicate participants have experienced obstetric violence care during childbirth [8].

Knowledge of women towards universal rights of childbearing: Twelve (12) items were prepared to assess women`s knowledge towards universal rights of childbearing. A continuous outcome variable is created for knowledge towards the universal rights of childbearing women. To better assess, characteristics with knowledge of participants were measured based on their mean score on universal rights of childbearing women. High mean scores on this scale indicate participants know the universal rights of childbearing women.

Attitudes of health care providers towards women were measured using a five-point Likert scale ranging from strongly agree with a 5- point scale to strongly disagree with one-point scale. The tool has 13 items. It was measured based on their mean score on childbearing women. The higher mean score is reflective of a more unfavorable attitude toward situations associated with obstetric violence.

The wealth index is measured using 18 survey questions about household assets, which was developed by Filmer and Prichett. Thus, a wealth index indicator variable was created to represent socioeconomic status based on questions assessing a woman’s household ownership of specific items (radio, television, bicycle, phone, refrigerator, scooter, automobile) as well as household characteristics (flooring and roofing materials, water sources, toilet facilities, electricity). The wealth index was generated using the final asset scores, which were based on an analysis of the whole sample to poorest, second, middle, fourth and richest.

Data collection and measurement

The data collection was undertaken using questions adapted from surveys and previous similar research which were validated in Kenya and Tanzania and from MCSP Maternal and Newborn Programs. The experts in the local language first translate the questions into the local language (Affan Oromo and Amharic) in the study location. To check the validity of the questionnaire, the local translated items were translated back into English to avoid its inconsistencies in the meaning and intentions [9].

Data were collected via face-to-face exit interviews to collect the socio-demographic and economic characteristics of the women, maternal-related factors and provider-related factors. Four data collectors and two supervisors participated in this data collection for 2 months in the study area. Before real data collection, two enumerators collected the data on 5% of the sample size for the pretest in Limmu Hospital which is 35 km away from the study area. At least the data collectors should have BSc/MSc/MPH and graduates in the field of health or sociology with effective communication of the local language (Afan Oromo and Amharic). The role of the supervisors is to oversee the data collection process and troubleshoot problems encountered by the research assistants.

To ensure the quality of items and data, three-day training was given to data collectors and supervisors about techniques of data collection. After the training was given, a pre-test was conducted on 5% of the sample size to ensure the validity of the tool, then correction was made before the actual data collection. The reliability test was considered particularly for knowledge and attitude, having the scores of Cronbach's alphas of 0.960 and 0.788 respectively.

Data management and statistical analysis

The data were entered in double into Epi-data version 3.1 and exported to SPSS version 23 software for analysis. Any errors identified during data entry were corrected by reviewing the original completed questionnaire. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the socio-demographic/economic, maternal characteristics of mothers and provider-related factors. Simple and multivariable linear regression analyses were used to identify the predictors correlated with the outcome variable. For the outcome variable, the Median score was used. The multicollinearity assumption was checked through the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) (the acceptable range is less than 10). Hence, the maximum VIF score for this research was 1.8, which showed no evidence for multicollinearity. Then, factors that showed significant associations in a simple linear regression model were added to multiple linear regression models to control the potential confounding factors using the enter method. Adjusted unstandardized beta coefficient (β) with 95% CI was calculated for each independent variable to see the adjusted association between exposure variables and the outcome variable. Variables that had a P-value of <0.05 in the multivariable model were considered statistically significant. Finally, results were compiled and presented using tables, graphs and text. Principal component analysis was used to compute the economic status of the study population using wealth index. Assumptions of PCA (Linearity, correlation) were checked prior to computing the wealth quantile [10].

Ethical and environmental considerations

To safeguard patients' rights and not harm, do good (beneficence) to patients and observe other, principles important to protect human participants were observed. Ethical approval for the study is sought from Jimma university IRB ethics committees before the commencement of data collection. The researcher provided prospective participants with sufficient information to make an informed decision to participate in the study. Written informed consent was obtained after an agreement was made by the participant to participate in the study after being informed about the purpose, benefits, risks and the process of data collection and confidentiality. Informed consent is part of autonomy as the participants are supposed to make informed choices without being coerced to participate in the study. For this study, participants were informed that participation was voluntary and it was obtained without any form of coercion undue influence or promise for any special kind of remuneration. The participants were informed that they could withdraw at any time without giving a reason and that there was no penalty or sanction for withdrawal [11].

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics

A total of 402 postnatal women were interviewed and completed the survey, with an overall average response rate of 98.8%.

The mean age of the women was 25.41 SD ± 4.89 years old. The majority 282 (70.1%) of the respondents were between 20-34 years old, followed by age group 19-20, 99 (24.6%). About 70.1% of the study participants were rural residents and more than eighty percent 329 (81.8%) of women were Muslim by religion. Almost all respondents 395 (98.3%) were married and greater than two out of five 165 (41%) of the study participants attended primary education. Regarding the occupational status of the women, more than three out of five 315 (78.4%) were housewives. As to the wealth status of the women, a majority 20.90% of them were in the poorest category of wealth quantile, which was followed by fourth, accounting for 19.65% (Table 1) [12].

| Variable | Category | Frequency | Percent |

| Age | 19-20 | 99 | 24.6 |

| 20-34 | 282 | 70.1 | |

| 35-49 | 21 | 5.2 | |

| Mean age | 25.41 SD ± 4.89 | ||

| Residence | Rural | 227 | 56.5 |

| Urban | 175 | 43.5 | |

| Religion | Muslim | 329 | 81.8 |

| Orthodox | 54 | 13.4 | |

| Protestant | 16 | 4 | |

| Other | 3 | 0.7 | |

| Marital status | Never married | 5 | 1.2 |

| Married | 395 | 98.3 | |

| Divorced | 2 | 0.5 | |

| Educational status | No education | 113 | 28.1 |

| Primary | 165 | 41 | |

| Secondary | 92 | 22.9 | |

| More than secondary | 32 | 8 | |

| Occupational status | Housewife | 315 | 78.4 |

| Farmer | 22 | 5.5 | |

| Business | 23 | 5.7 | |

| Student | 12 | 3 | |

| Employed | 30 | 7.5 | |

| Wealth | Poor | 84 | 20.9 |

| Second | 77 | 19.2 | |

| Middle | 80 | 19.9 | |

| Fourth | 82 | 20.4 | |

| Richest | 79 | 19.7 | |

| Note: Other: Pagan, Jehovah | |||

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of women in Jimma Zone public hospitals, South West Ethiopia, 2023 (n=402).

Maternal characteristics

All women who underwent the study research had received antenatal care. Among women who received antenatal care, 291 (72.4%) of them visited health facilities 2-3 times during their entire pregnancy. The median antenatal care visit was three. Hundred fifty (37.3%) of the study subjects had at least parity the same number of mothers (150) had a parity of 2-3. One hundred twenty (29.9%) of the respondents had a history of home delivery before the index birth. As to the referral status of the mothers, the majority 282 (70.9%) of them were self-referral. Greater than two-fifths (41.5%) of the women reported the distance from home to the health facility location to be not long at all. Among the women who gave birth in the study facilities, 244 (60.7%) of deliveries were conducted by males, 76 (18.9%) births were on Sunday and the majority 235 (58.5%) of births were conducted at nighttime. Regarding mother complications, 287 (71.4%) of the women had not experienced any type of obstetrics complications during or after childbirth but approximately three out of ten (28.6%) mothers developed complications that arise during the intrapartum and postpartum period. Regarding the intention of women on birth, most of the women 340 (84.6%) had a plan to have more children. Out of the women who had an intention to have more children, 227 (56.5%) were planning to deliver in the facility where they gave birth before. According to the report from women, the majority of disrespect and abuse the women experienced during labour and childbirth were committed by female health care providers, 148 (36.8%). Concerning companion utilization, a greater number of women 379 (94.3%) was not allowed to have a companion during childbirth in the delivery room (Table 2) [13].

| Variable | Category | Frequency | Percent |

| No. of ANC contact | 1 | 54 | 13.4 |

| 2-3 | 291 | 72.4 | |

| ≥ 4 | 57 | 14.2 | |

| Median ANC contact | 3 | ||

| Parity (Birth order) | 1 | 150 | 37.3 |

| 2-3 | 150 | 37.3 | |

| 4-5 | 68 | 16.9 | |

| >6 | 34 | 8.5 | |

| History of home delivery | No | 282 | 70.1 |

| Yes | 120 | 29.9 | |

| Referral status of the mother | Self-referred | 285 | 70.9 |

| Referred from other HFs | 117 | 29.1 | |

| Distance from home to this health facility | Very long | 32 | 8 |

| Long | 98 | 24.4 | |

| Not very long | 105 | 26.1 | |

| Not long at all | 167 | 41.5 | |

| Sex of health care provider conducted delivery | Male | 244 | 60.7 |

| Female | 158 | 39.3 | |

| Day of the week mother gave birth | Sunday | 76 | 18.9 |

| Monday | 67 | 16.7 | |

| Tuesday | 62 | 15.4 | |

| Wednesday | 60 | 14.9 | |

| Thursday | 48 | 11.9 | |

| Friday | 48 | 11.9 | |

| Saturday | 41 | 10.2 | |

| Time of birth | Day time | 167 | 41.5 |

| Night time | 235 | 58.5 | |

| Obstetric complications during delivery | Yes | 115 | 28.6 |

| No | 287 | 71.4 | |

| Sex of the abuser | Male | 126 | 31.3 |

| Female | 148 | 36.8 | |

| Both | 128 | 31.8 | |

| Intention to have more children | Yes | 340 | 84.6 |

| No | 62 | 15.4 | |

| Future place of delivery (n=340) | This facility | 227 | 56.5 |

| Another facility | 54 | 13.4 | |

| Home | 59 | 14.7 | |

| Companion utilization during childbirth | No | 379 | 94.3 |

| Yes | 23 | 5.7 | |

| Knowledge of the women toward universal rights of childbearing | 0.5431 ± SD 0.40630 | ||

| Healthcare providers attitudes towards women | 2.4734 SD ± 0.45499 | ||

Table 2: Obstetric characteristics of women in Jimma zone public hospitals, South West Ethiopia, 2023 (n=402).

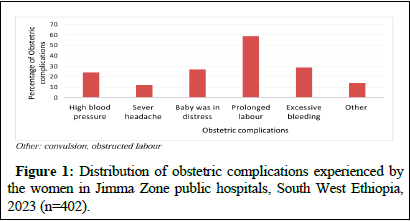

Among women who developed obstetrics complications, 59 (14.7%) of them experienced pronged labour, which was followed by excessive virginal bleeding, 29 (7.2%) (Figure 1) [14].

Figure 1: Distribution of obstetric complications experienced by the women in Jimma Zone public hospitals, South West Ethiopia, 2023 (n=402).

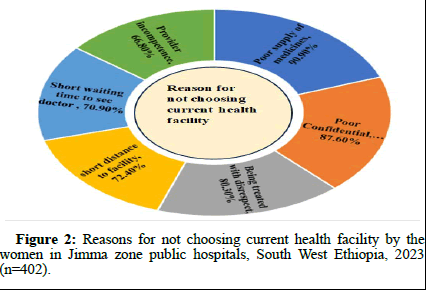

When it came to women who hadn't planned to give birth in a service delivery point, their main complaints were about the lack of privacy and confidentiality they experienced as well as the being treated with disrespect/poor treatment they received while giving birth (Figure 2) [15].

Figure 2: Reasons for not choosing current health facility by the women in Jimma zone public hospitals, South West Ethiopia, 2023 (n=402).

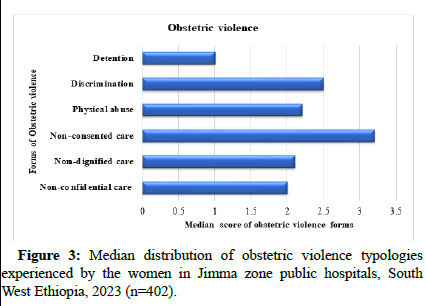

Status of obstetric violence

As per the report from the women; all the study participants experienced at least one form of obstetric violence. The median score of obstetric violence score was 2 with a range scale of 1 to 5. To be reliable in the report, the total scores were converted to a scale of 30 to 150. Accordingly, the overall median of obstetric violence score was 69. The typologies of obstetric violence median scores were: Nonconfidential care 2, non-dignified care 2.1, non-consented care 3.2, physical abuse 2.2, discrimination 2.5 and detention 1 on the scale rage of 1-5. The highest obstetric violence referred to non-consented care followed by discrimination and non-dignified care and the least reported one was detention (Figure 3) [16].

Figure 3: Median distribution of obstetric violence typologies experienced by the women in Jimma zone public hospitals, South West Ethiopia, 2023 (n=402).

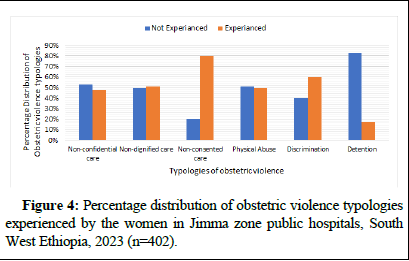

Manifestations of obstetric violence typologies

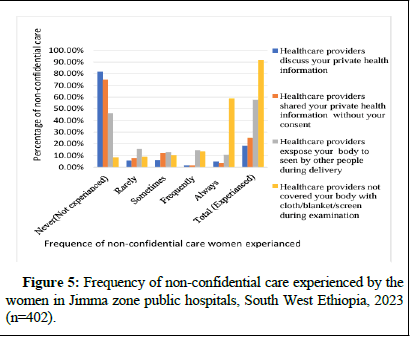

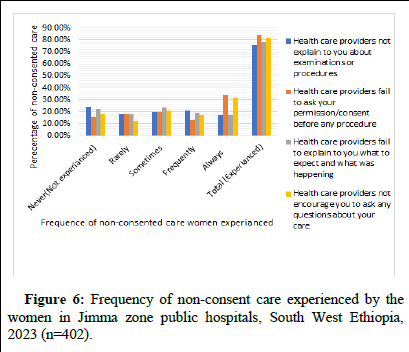

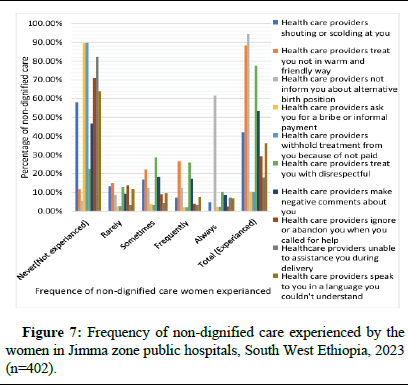

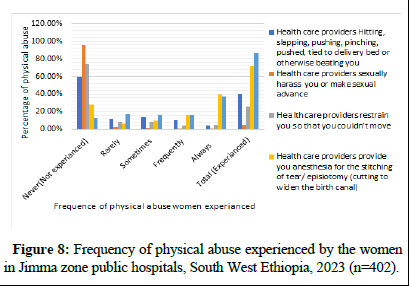

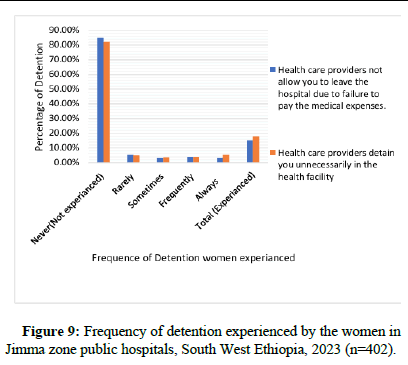

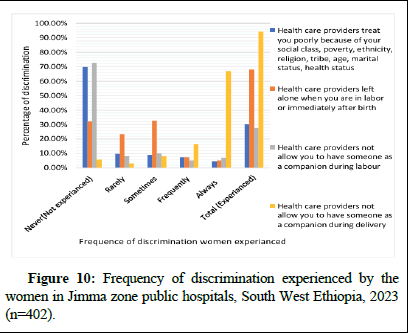

According to the study's findings, non-consented care was the most frequent form of obstetric violence that the women encountered. "Failure to ask mothers permission/consent before any procedure during labor and childbirth, which accounts (340 (84.6%))" was the most frequently reported mistreatment among the non-consented subscale manifestations, followed by "failure to encourage the mother to ask any questions about her care," 330 (82.1%). Discrimination was the second most frequently reported type of obstetric violence. In this category, the most common complaints from women about mistreatment were from medical professionals who refused to let the mother have a companion during childbirth (379, 94.3%). The results of this study showed that physical abuse and inhumane treatment were the third and fourth most often reported forms of obstetric violence, respectively. According to these typologies, failing to inform a mother about alternate birth positions (380; 94.5%) and not doing everything in their power to alleviate a mother's pain (348; 86.6%) were the most common forms of disrespect and abuse. Non-confidential care and detention were the categories of obstetric violence that were least reported in the current study. The prevalent mistreatments reported by the women under these subscales include: 368 (91.5%) of not covering the mother's body with cloth, blankets or screens during examinations or childbirth; and 72 (17.9%) of mothers being unnecessarily detained in medical facilities by healthcare providers respectively (Figures 4-10) [17].

Figure 4: Percentage distribution of obstetric violence typologies experienced by the women in Jimma zone public hospitals, South West Ethiopia, 2023 (n=402).

Figure 5: Frequency of non-confidential care experienced by the women in Jimma zone public hospitals, South West Ethiopia, 2023 (n=402).

Figure 6: Frequency of non-consent care experienced by the women in Jimma zone public hospitals, South West Ethiopia, 2023 (n=402).

Figure 7: Frequency of non-dignified care experienced by the women in Jimma zone public hospitals, South West Ethiopia, 2023 (n=402).

Figure 8: Frequency of physical abuse experienced by the women in Jimma zone public hospitals, South West Ethiopia, 2023 (n=402).

Figure 9: Frequency of detention experienced by the women in Jimma zone public hospitals, South West Ethiopia, 2023 (n=402).

Figure 10: Frequency of discrimination experienced by the women in Jimma zone public hospitals, South West Ethiopia, 2023 (n=402).

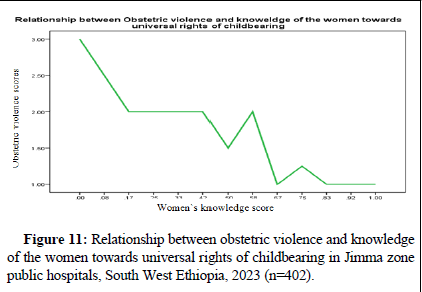

This study revealed that obstetric violence scores decreased as the knowledge of the women towards universal rights to childbearing scores increased. This indicates women's knowledge about their universal healthcare rights to childbearing significantly reduced their obstetric violence (Figure 11) [18].

Figure 11: Relationship between obstetric violence and knowledge of the women towards universal rights of childbearing in Jimma zone public hospitals, South West Ethiopia, 2023 (n=402).

Factors correlated with obstetric violence

On multivariable linear regression analysis, several ANC contacts, knowledge of the women towards universal rights of childbearing women, intention to deliver at home and unfavorable attitude of health care providers remained to have statistically significant association with obstetrics violence.

The amount of obstetric violence that women experienced decreased by 0.135 times (β=-0.135, 95% CI=-0.232,-0.038) when the number of antenatal care contacts was increased by one. When women's awareness of the universal rights of childbearing women increased by one unit, there was a 0.644-fold decrease in experience of obstetric violence (β=-0.644, 95% CI=-0.916, -0.372). Keeping other variables constant, mothers who have been victims of obstetric violence intend to give birth at home. Thus, among women whose intention was to give birth at home, obstetric violence scores have increased by a factor of 0.375 (β=0.375, 95% CI=0.167, 0.584). The women's report indicated that the obstetric violence score of healthcare providers with negative attitudes was higher by a factor of 0.60 when compared to those with positive attitudes (β=0.600, 95% CI=0.422, 0.777). (Table 3) [19].

| Variables | Unstandardized adjusted (β) coefficient | 95.0% CI for coefficient (β) |

| Age of the mother | 0.006 | (-0.004, 0.017) |

| Rural residence | 0.025 | (-0.085, 0.134) |

| Frequency of ANC contact | -0.135 | (-0.232, -0.038)* |

| Night time birth | 0.07 | (-0.039. 0.178) |

| Duration of hospital stay | 0.006 | (-0.007,0.019) |

| Knowledge of women's universal right to childbirth | -0.644 | (-0.916, -0.372)* |

| Intention to deliver in this health facility | 0.012 | (-0.144, 0.168) |

| Intention to deliver in other health facilities | 0.0186 | (-0.013, 0.385) |

| Intention to deliver at home | 0.375 | (0.167, 0.584)* |

| Not experiencing obstetrics complications | -0.07 | (-0.223, 0.084) |

| Unfavorable attitude of healthcare providers | 0.6 | (0.422, 0.777)* |

| Presence of companion during delivery | -0.04 | (-0.197, 0.117) |

| Note: CI: Confidence Interval; *significant at P-value<0.001 | ||

Table 3: Multivariable linear regression analysis factors for obstetric violence scale in Jimma zone public hospitals, Southwest Ethiopia, 2022.

Discussion

This study examined obstetric violence as a detrimental practice and human rights violation within the healthcare system that negatively impacts the health-seeking behavior of innocent women who are pregnant, in labor or have recently given birth. On a national and international scale, this practice may increase maternal mortality and morbidity. In addition to suggesting potential interventional strategies to lessen the obstetric violence committed by health cadres, the study sought to address factors associated with obstetric violence among postpartum women in public hospitals of the Jimma zone.

The study highlighted that for every woman, there was at least one form of obstetric violence experience, with scores ranging from 44 to 109 on thirty (30) items. Comparable research carried out in various regions of Ethiopia, Nepal and India also revealed that every woman reported at least one type of mistreatment and disrespect during labor and delivery. Because of this, obstetric violence has been identified in multiple studies as a barrier to the uptake of maternal healthcare services, particularly facility childbirth.

The study's results indicate that the range of obstetric violence scores was 1 to 5, with a median of 2.00. The subscale for nonconsented care had the highest rate of obstetric violence (median=3.2), followed by the subscale for discrimination (median=2.5) and the subscale for detention had the lowest rate of obstetric violence. In the non-consented subscale manifestations, "failure to ask mothers permission/consent before any procedure during labor and childbirth, which accounts for (340 (84.6%))" was the most frequently reported mistreatment. This is consistent with research carried out in Gondar city, Ethiopia, south Wallo, Ethiopia and Arban Minch, Ethiopia. Corroborating our findings, research from Amhara, Ethiopia revealed that non-consented care accounted for the majority of reported cases of obstetric violence. This was explained by the researcher as "failure to obtain consent/permission before any procedure (185, (63.8%))". The similar standard tool used in both studies-which used comparable domains of obstetric violence indicators and studies conducted on the same types of public health facilities-may be the cause of the consistent findings.

The final model's findings demonstrated that when the score for obstetric violence increased, the score for prenatal care significantly dropped. This suggests that the likelihood of women experiencing obstetric violence increases as the frequency of ANC contact decreases. This is in good agreement with a study from the Gedeo zone in South Ethiopia which found that obstetric violence was more common among mothers who did not receive ANC follow-up. Likewise, the research carried out in Gondar city, Ethiopia, demonstrated that women who had fewer than four ANC follow-up contacts were more likely to experience mistreatment than those who had four or more. Furthermore, an Ethiopian study found that women who received ANC follow-up had a higher chance of receiving Respectful Maternity Care (RMC). This could be the case because ANC follow-up gave mothers the opportunity to track down the various forms of violence that women could experience. An alternative hypothesis would be that women who make more frequent contacts with healthcare providers develop stronger bonds and connections with healthcare professionals, which in turn help them, develop self-confidence and trust. The similarity in the methodological approaches and culture of the health setting could be the reason for the consistent results across the findings.

According to Article IV of the UN's Universal Declaration of the Rights of Childbearing Women, every woman has the right to be treated with respect and dignity. The framework of mistreating women during childbirth also involves a number of human rights, such as the right to privacy, confidentiality, information and nondiscrimination, the right to the best possible standard of health and the right to be free from violence. A study carried out in the West Bank, Palestine, suggests that raising awareness of women's fundamental rights during childbirth, normalizing the process and enhancing the working environment and conditions of childbirth facilities can all help reduce the incidence of mistreatment. According to a different study by Okedo Alex, et al., women who are less conscious of their rights are more likely to encounter obstetric violence during labor and delivery. This is in line with our finding that obstetric violence during childbirth in medical facilities is considerably reduced when women are aware of their universal right to bear children. Obstetric violence can be lessened to a greater extent by women who are aware of their universal rights as childrearing and who skillfully and efficiently exercise those rights when using maternal health services.

In comparison to their counterparts, respondents who intended to give birth at home scored higher on obstetric violence. This result is in line with the earlier Ethiopian study that showed that women who had been the victims of obstetric violence were unable to seek professional assistance during childbirth and instead opted to give birth at home. These consistent results could be explained by the psychological trauma that the women went through during childbirth as a result of the negative attitudes and perceptions of healthcare professionals toward providing care for women giving birth. However, a study done in the city of Bahir Dar revealed that women there intended to use medical facilities for childbirth three times more frequently in the future than did women counterparts. This difference may be the result of different study settings and women's varying degrees of awareness regarding the significance of giving birth in a facility. The study area's nearly 100% obstetric violence prevalence contrasts with Bahir Dar city's 43% research, suggesting another explanation for the variation.

The occurrence of obstetric violence is triggered by a negative, unfriendly and poor provider attitude, according to a systematic review and qualitative study on the factors that predispose women to disrespect and abuse during childbirth. This negatively affects the women's behavior when seeking health care, ultimately endangering the lives of the mothers and fetus. This supports the results of the current study, which found that there was a 0.6 increase in obstetric violence scores among healthcare professionals with negative attitudes toward their patients. Lack of training in respectful maternity care and the demanding nature of the healthcare industry-which includes seeing a lot of patients, working long hours, and having heavy workloads-are major causes of negative behavior. The findings have wider practical implications such that obstetric violence-related issues in facilitybased childbirth are not addressed, it is unlikely that the global community including Ethiopia can achieve SDG goals for skilled care coverage and reduction of maternal mortality rate. Cognizant of these facts, the Federal Ministry of Health (FMOH) Ethiopia incorporated compassionate and respectful care in the Health Sector Transformation Plan (HSTP). Thus, urgent action is needed to overcome the challenges of obstetric violence in facility childbirth especially in Ethiopia.

Conclusion

Every woman who took part in this study experienced at least one type of obstetric violence, despite the fact that the median OV score was two. A woman's knowledge of the universal rights of childbearing women, her intention to give birth at home, the number of ANC contacts she has and the negative attitudes of healthcare professionals are all independently linked to obstetric violence. We call on all stakeholders-healthcare providers, institutions, the community, women and civil society-to take action in order to address the obstacles. We propose transforming the culture and norms surrounding obstetric care, advocating for the new WHO ANC model and evidence-based practices and optimal respectful maternity care through a right-based framework and educating women about their rights to universal healthcare. The relevant authorities must also take a comprehensive approach to obstetric violence, taking into account the common understanding of gender-based violence. Furthermore, it is crucial to foster a culture of respect, trust and understanding between healthcare providers and birthing women in health facilities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: AT and TB

Data curation: AT

Formal analysis: AT

Methodology: AT and TB

Supervision: TB

Writing-original draft: AT

Writing-review and editing: AT and TB

Acknowledgements

First and foremost, praises and thanks to God, the almighty, for his showers of blessings throughout my research work. Next, I would like to thank all mothers who participated in the study for their cooperation in providing the necessary information. I would also thank data collectors and supervisors for their commitment, devotion and quality work during the data collection period. Lastly, I am extremely grateful to my parents, my brothers and my sisters for their love, prayers, caring and sacrifices in educating and preparing me for my future.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethic Statement

The study was approved by Institutional Ethical Review Board, Institute of Health, Jimma University, Ethiopia, (Protocol no. IRB/ 000/200/2020)). The respondent's identity was maintained anonymous. Before each interview, participants were asked for permission and they had the option to withdraw at any moment.

Transparency Statement

The lead author Ayanos Taye affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

References

- Mrisho M, Schellenberg JA, Mushi AK, Obrist B, Mshinda H, et al. (2007) Factors affecting home delivery in rural Tanzania. Trop Med Int Health 12: 862-872.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Eshete T LM, Ayana M (2019) Utilization of institutional delivery and associated factors among mothers in rural community of Pawe Woreda northwest Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes 12.

[Crossref]

- Wilson-Mitchell K EL, Robinson J, Shemdoe A, Simba S (2018) Overview of literature on RMC and applications to Tanzania. Reprod Health 15: 167.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kruk ME, Paczkowski M, Mbaruku G, de Pinho H, Galea S (2009) Women's preferences for place of delivery in rural Tanzania: A population-based discrete choice experiment. Am J Public Health 99: 1666-1672.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kruk ME, Paczkowski MM, Tegegn A, Tessema F, Hadley C, et al. (2010) Women's preferences for obstetric care in rural Ethiopia: A population-based discrete choice experiment in a region with low rates of facility delivery. J Epidemiol Community Health 64: 984-988.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shiferaw SS, Godefrooij, Melkamu M, Tekie Y (2013) Why do women prefer home births in Ethiopia? BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 13.

[Crossref]

- Karanja S, Gichuki R, Igunza P, Muhula S, Ofware P, et al. (2018) Factors influencing deliveries at health facilities in a rural Maasai Community in Magadi sub-County, Kenya. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 18: 1-11.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Afulani PA, Kelly AM, Buback L, Asunka J, Kirumbi L, et al. (2020) Providers’ perceptions of disrespect and abuse during childbirth: A mixed-methods study in Kenya. Health Policy Plan 35: 577-586.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kassa ZY, Husen S (2019) Disrespectful and abusive behavior during childbirth and maternity care in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Res Notes 12: 1-6.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Abuya TWC, Miller N, Njuki R, Ndwiga C, Maranga A, et al. (2015) Exploring the prevalence of disrespect and abuse during childbirth in Kenya. PLoS One 10.

[Crossref]

- Jardim DM, Modena CM (2018) Obstetric violence in the daily routine of care and its characteristics. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem 26: e3069.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Feldman N, Padoa A (2022) Obstetric violence-since when and where to: implications and preventive strategies. Harefuah 161: 556-561.

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ferrão AC, Sim-Sim M, Almeida VS, Zangão MO (2022) Analysis of the concept of obstetric violence: Scoping review protocol. J Pers Med 12: 1090.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Galiano JM, Martinez-Vazquez S, Rodríguez-Almagro J, Hernández-Martinez A (2021) The magnitude of the problem of obstetric violence and its associated factors: A cross-sectional study. Women Birth 34: e526-536.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Asefa A, Bekele D, Morgan A, Kermode M (2018) Service providers’ experiences of disrespectful and abusive behavior towards women during facility based childbirth in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Reprod Health15: 1-8.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wassihun B, Zeleke S (2018) Compassionate and respectful maternity care during facility based child birth and women's intent to use maternity service in Bahir Dar, Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 18: 294.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Okafor II, Ugwu EO, Obi SN (2015) Disrespect and abuse during facility-based childbirth in a low-income country. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 128: 110-113.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sando D, Ratcliffe H, McDonald K, Spiegelman D, Lyatuu G, et al. (2016) The prevalence of disrespect and abuse during facility-based childbirth in urban Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 16: 1-10.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Siraj A, Teka W, Hebo H (2019) Prevalence of disrespect and abuse during facility based child birth and associated factors, Jimma University Medical Center, Southwest Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 19: 185.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Citation: Taye A, Belachew T (2025) Addressing Predictors of Obstetric Violence among Postpartum Women in Public Hospitals of Jimma Zone, Southwest Ethiopia: Call For Action. J Preg Child Health 12: 697.

Copyright: © 2025 Taye A, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Usage

- Total views: 147

- [From(publication date): 0-0 - Dec 08, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 98

- PDF downloads: 49