Architectural Identity Shaped by the Political System, Kurdistan Region Since 1991 as a Case Study

Received: 25-Oct-2017 / Accepted Date: 08-Feb-2018 / Published Date: 16-Feb-2018 DOI: 10.4172/2168-9717.1000216

Abstract

“We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us” Winston Churchill 1943. The ruling Elites utilize meaning in architectural forms to exercise their political power to unite and or manipulate people, here architectural signification plays a major role in the nationhood in creating and reaffirming the cultural identity for societies.

Kurdistan is a roughly defined geo-cultural region wherein the Kurdish people form a prominent majority population, and Kurdish culture, languages, and national identity have historically been based.

Following the discovery and exploitation of oil, paralleled with investment law in 2004, Kurdistan witnessed a bulk boom in the construction industry. Kurdistan region became architecture playground. Most of the pilot projects were prepared behind boarders by various international architectural styles, diminishing the regions local identity. One of the areas that suffered from the previous control system is neglecting and deconstructing of architectural identity.

The paper is based on case study and observations. An inductive method will be used to analyze pilot projects in Kurdistan and how they reflect the political system’s desires instead of the culture and identity of the region. Hence Architectural identity is shaped by the political system.

The paper is using Kurdistan as case study following 1991 uprising after the creation of safety zone by UN. Projects from Erbil, Sulaimania, and Duhok will be analyzed to create a clear image for the main features of architectural identity’s dilemma within the current political system. Challenges and problems facing the development of the local architecture to be addressed; recommendations will conclude the paperwork.

Keywords: Architectural Identity; Political system; Local identity; Kurdistan region

Inroduction

Architectural identity of any nation is a direct product and reflection of the applied political system in the country and how democratic is the decision making in the country. Absent of the democracy in large number of countries such as in the Middle East, Africa and several countries in Asia has reflected in creating a situation where architectural identity decided by particular groups [1].

Changing the elite groups has also associated with changing the city architecture. This phenomenon has existed during history with different consequences including demolishing and transformation of the original city shape and its architecture and building entirely new cities and applying new architecture of the elite.

The Kurdish issue continues to be one of the most complex political issues that the Middle East faces today. However, Iraqi Kurdistan, after living for decades in unstable conditions, the three northern governorates of Iraqi Kurdistan, which are Erbil, Dohuk, and Sulaimania, experienced semi-liberation for the first time in 1991 as a consequence of the successful uprising of Iraqi Kurds and the removal of Saddam’s regime [2].

In the period between1991 and 2003, in spite of the establishment of the “no fly zone” (Mufti 2008) provided by the United nation, the formulation of an emerging democratic region faced challenges in implementation. As in 1994, the civil war between the two dominant parties, concluded in 1998 by dividing the region into two different political, social, and economic systems, which belonged to two different governments led by KDP in Erbil and Dohuk, and PUK in Sulaimania [3]. With the collapse of Saddam’s regime in 2003, a new phase of Kurdish history has been recorded and the Kurdistan Regional Government has been unified in 2006 [3].

Iraqi Kurdistan has made extensive efforts to find its social, economic and political place on the global map since 2003. It is unfortunate that the built environment, which has to be the physical icon of Kurdish history, is difficult to identify. The shared oil revenues have allowed the region to start its reconstruction and development programs much earlier than other regions. That was the result of peaceful situation, economic growth, regional and global changes. Architecture in Kurdistan reflected all these layers of rapid political, economic and cultural changes. These rapid developments led to the existence of a state of chaos and confusion in the architectural forms that reflected in many cases, a strange ideological orientation forged with the specificity and privacy of the historical origin.

Thus, this paper offers a new theoretical horizon for better understanding the powerful force of architecture as central in transforming the physical image of nation’s identity. It is an attempt to initiate an effective link between architectural identity and politics to advance a new political critique of architecture capable of addressing the challenges posed by globalization by incorporating political content to architectural identity.

Identity

Identity is based on how someone or something communicates, how it ‘speaks’. There are a few main categories of which architectural identity could be classed under; aesthetics, function, historical and urban context, human impact and representation [4]. The concept of identity in the field of social and political sciences is easy yet difficult. It is easy because it makes sense for everyone. Yet, it is difficult because on the more it is elaborated it gets complicated and difficult to understand. Identity can be defined as a set of material, biological, psychological and cultural signs distinguishing every individual, group, population or culture from others. It is different depending on the society or nation in question and is an expression of a kind of unity, solidarity, uniformity, persistence, integrity, and non-divisiveness.

Identity refers to human beings’ perception, therefore, it has two aspects: first, it is an instrument to keep control of people’s mind, and second, it is a source of power for formulating new societies. The question of identity is often interpreted to be a question about people's concepts of “who they are” and how they relate to others [5]. Identity is a way of preserving the continuity of the self. It means lifestyle or life values that link the past to the present [6].

We may use identity as an instrument (or societal-guidance) to boost motivation. It is considered according to Etzioni's theory three factors, which count, as sources of identity are knowledge, commitment, and power. One may need incentives to exert those three factors. Recent literature on psychology is also prone to list identity as human needs (e.g. Maslow, Erikson, etc.). Nowadays, identity has more political overtones than psychological or even than cultural ones.

“The search for identity is a by-product of looking at our real problems, rather than trying to find identity as an end in itself, without worrying about the issues we face” [7]. Identity is a people's source of meaning and experience. Identity is the result of a self-conscious way of thinking, of separation between man and nature, an ontological one. Identity in this sense, incredibly, for better or worse, becomes a human need; it has unbelievably transformed itself into a necessity.

In general three levels can be outlined for cultural identity: - Identity is a membership to different intellectual, professional, social, political, cultural, and other groups. It is the most tangible one. The second level is conscious but is not under our control. This level of cultural identity is created during the lifetime of several generations and any change in it takes generations. Finally, Identity is unconscious and extraordinary that is the reason why it is often neglected. This order of cultural identity takes long periods of time to develop and it is richer for societies with longer historical experience and the persistence on land [8].

Identity consists of complicated characteristics and different feature. As a result, identity has taken into consideration history, heritage, culture, religion, ethnicity, language, and consciousness [9]. Identity reflects the cultural heritage and cultural common codes. It is inclined to stability over time because, as a legacy, it has been selected and reinforced by many generations. [10] Architecture can become a resource for understanding cultural identity [11]. The questions of identity are examined through the identity theory and social identity theory [12].

Architectural Identity

The construction of this identity was a highly symbolized act that used a series of elements considered to be highly symbolical themselves, such as language, folklore, historical monuments, etc. Among them, architecture occupied an important place [13]. Architecture has always been utilized as a nexus of a re-examination of the nature and definition of identity of any nation [14]. It is a feature of the environment that does not change in different situations. This feature can be physical features such as shape, size, decoration, construction style, etc. or it can be specific activities or practices in the environment or its functions [15]. History saved nations to define them, to build up their identity [16].

Architecture is a human product which symbolized human mentality in the past, present and his future opinion in a lively way to that human mentality identification. Furthermore, this is a historical truth which represented the distinguishing of architecture product between communities [17]. Argues that Identity is a key concept of the modern era; it has become a common topic in the architectural discussions of the last few years. The main reasons for this obviously sudden interest for the subject were the significance of the ‘aftermodern’ syndrome, with the crisis of modernism in architecture reinforced by the maturation effects of globalization. On the other hand, the numerous recent humanitarian studies focused on architecture as a base structure of identity through a reconsideration of architecture as a fundamental means of identity [18].

Architecture is a vehicle and an instrument of identity, it conveys the features of identity as a vehicle and functions as a model to impose a certain image of identity as an instrument [17]. For Gur, [19] identity is “a syntactic series of meanings and images assigned to a legible space as a result of perception in mind". It is the special context and meaning of an environmental image that links with the symbolic characteristics of form. It aims to express the sense of essentials of cultural values [20]. The architectural identity of particular local culture represents a living landscape with a common sense of place [14].

For Carmen [17], time and space are the main references informing architectural identity. Time is related to history and thus brings authenticity to the identity construction, whereas Space is related to geography, which grants the identity construction with an analytical spirit and suitability. Both approaches are founded on principles: time reinforces ideology whereas space prefers aesthetics, However, Tran has explained, Architectural identity is often conceived and represented as a timeless and historically stable entity. This is reflected in particular practices of building design and heritage conservation. Architectural identity is revealed as an intangible and unstable entity, rather than an aesthetically prescribed, trans-historical construct [21]. Architectural identity has two conflicting vectors; the first is the vector of similarity and continuity, whereas the second is the vector of difference and rupture. Hence, architectural identity can be defined as a link between the past and the future. For Elkadi [22], building visual elements have distinctive effects on the issue of identity.

Each particular nation has applied different methods and process to produce its modern particular national architectural identity. This process has been influenced by the applied system of decision making. Nations with open and democratic decision-making tradition have managed to give users larger influence in its architectural development process. This open process has played a vital role to decide the national architectural identity. Although, there are different critiques about how open is the process. But having the democratic system can give the society different possibilities to influence the decision making through media, education, organizations and free speech. While in other nations with not democratic systems, producing the national architectural identity has been produced largely by a small number of the decision-maker [23].

With little or no local participation, The National architect identity has been influenced by the applied decision-making system that has enabled the elite groups to decide the architectural identity of the entire country [24]. The modern national architectural identity in non-Western countries reflects a direct influence by the Western architecture. Applying this architecture in these countries was done basically by top-down decision-making process with little or no local participation. Therefore, the national architectural identity in a large number of these countries has been influenced by the applied decision-making system that has enabled the elite groups to decide the architectural identity of the entire country [23].

The change and continuity are two main forces that affect architectural identity, changing forces pushing the identity toward new horizons depending on modern technologies, in the same time stabilization forces derive its power from traditions and conventions.

The Power of Architect

The relation between the power and architecture can be constructed in two principle ways, a traditional approach follows a functional logic: buildings, urban design, and in practical official architecture for governmental use find a form which reflects both underling purposes and the underling ideology of the regime: “every architectural work can be regarded as a sign of the power, wealth, idealism, even the misery of its builders and their contemporaries” [25]. Every building not only serves its purpose but also reflects the worldview of its builders and users. It can also confer a meaning or legitimacy to the authorities that build or use it [14]. On much grander scale such perspective has typically identified the monumentalism of totalitarian regimes of interwar period (most notably fascist Italy, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union) [25,26].

The analysis of the power of architecture is the issue of politicization of space at the intersection of the fields of politics and urban planning, art, and the architecture, or more precisely the spatial relation of an official building to its built (and un-built) environment. This relationship and the conferring of meaning to it must be seen as intrinsically political: urban spaces were just as often reconfigured by such political clashes, as rival groups divided by distinctions of race, class, and politics sought to make such political divisions concrete in physical structures and orders of the city. This approach situates politics and political discourse in the spatial landscape of the city [26].

The attempts to politicize architecture have emerged from the hypothesis that architecture is a ‘social construct’, a cultural fabrication and an embodiment of political concepts, disassociated from an architecture governed by natural laws, statics and climatic demands [27]. But architecture is as much a physical construct as it is a social or political one and to understand architecture as a mere representation of the political is as problematic as to declare architecture entirely ruled by natural laws. Political meaning has a long history of being part of the equation of the built environment and continues right through to the present to be a matter for architects and politicians across the world [14].

A building speaks for what it is, and for what it stands for. It has a function/purpose, it can represent an idea thought how it looks and works; and it can represent its function [27]. It is true that the form and extent of architecture depends on factors like resources and technology, but architecture cannot happen unless somebody is willing to pay for it, and thus right from the beginning of the human civilization architecture has always depended on the vision of its patrons [28].

Architecture is a profession that is inherently engaged in public diplomacy by the nature of what it creates and who interacts with it, and that therefore, architects need to consciously participate in public diplomacy through their work rather than unwittingly be a part of it with no awareness of their significance. The fact is too many architects are seriously marginalized, intentionally isolated, from the political process that determines the zoning, funding and the complex social and legal regulations that control the building of our shared environment. This subject needs to be confronted, debated and discussed in detail [29].

The architectural profession would do well to develop the future influence of our profession in plan suggestes that our fellow architects take up leadership roles in order to balance the economic and political aspects of city/state planning more consciously. By expanding “design” from its aesthetic sense to incorporate people, society and quality of life issues, we shift the paradigm of architecture from the design of buildings to influencing the “design” process for solving problems in society. Architecture need be un-limited simply to buildings and grand constructions, but rather that architectural design and design considerations should permeate every aspect of life [29].

A building can make a statement to potential customers, clients, employees, or rivals. The architecture utilized in a corporate building can indicate general philosophies held by the corporation or principles it wishes to espouse [30]. The Chrysler building gave the Chrysler Corporation a giant piece of advertising and propaganda. Not only could Chrysler claim to the tallest building in the world at the time of its completion, but the stainless steel spire of the building was styled after the grilles of then current Chrysler road cars. This huge building served as a massive statement of the success and power of the Chrysler Corporation while at the same time advertising its products to the world through the architecture of the building [31].

Architectural policy

Architectural policy establishes guidelines for the protection of our architectural heritage, and for the maintenance and enhancement of the value of our existing building stock. It also provides opportunities for improving the existing high architectural standards of building as well as creating a suitable climate to enable our construction sector to compete effectively in a wider international setting. Careful maintenance of the built environment is the basis of the constructional culture.

In the last 30 years there has been a growing recognition of the importance of architectural quality for social and cultural development, wealth creation and economic well-being. To support this goal, several European countries have been developing architectural policies to promote spatial design excellence and raise public awareness of the importance of the built environment.

Reflecting on the wide diversity of cultures across the European Union, some Member States have developed initiatives and actions addressed to clients and stakeholders, others have produced guidance and educational programs, while others have promoted new architectural cultural agendas oriented to the general public. The differences in approaches result from the Member States still differing in many aspects: to identify a growing tendency for the development of architectural policies, with the national, regional and local governments assuming a catalytic role.

The European Forum for Architectural Policies (EFAP) is an international network devoted to foster and promote architecture and Architectural policies in Europe, bridging public governance, profession, culture and education. Among several objectives, the EFAP aims to disseminate knowledge and best practice on architectural policies through meetings of experts, public events and publications.

Inspired by the first article of the 1977 French Law on Architecture [2], the EU Directive states that “Architecture, the quality of buildings, the way in which they blend in with their surroundings, respect for the natural and urban environment and the collective and individual cultural heritage are matters of public concern” [32].

The Resolution recognizes the importance of architecture to improve the quality of the day-to-day environment in the life of European citizens. Sustainable European Cities, which calls on Member States to pay greater attention to the creation of a culture of a high quality built environment “giving particular attention to the quality of the public space, notably in terms of architectural design quality, as a means of improving the well-being of European Union citizens [32].

Architecture, as a discipline involving cultural creation and innovation, including a technological component, provides a remarkable illustration of what culture can contribute to sustainable development, in view of its impact on the cultural dimension of towns and cities, as well as on the economy, social cohesion and the environment [33].

Architectural propaganda: Architectural propaganda is the use of architecture, intentionally or unintentionally, to communicate an attitude or idea in a persuasive manner, often for an explicitly propagandic purpose. The use of architecture for propaganda purposes in order to influence attitudes, opinions, and feelings of the target audience can be found in many cultures across history. Since architecture itself is an expression of culture, the propaganda element of architecture can organically flow from the structure by nature of its being.

The psychological dimension of architecture and propaganda means that even when a group or government has no direct intent to use architecture for propaganda purposes, the nature of architecture proceeding as it does from the human mind will express something about the designer and his or her culture. The architecture itself becomes an expression of the larger opinions of a cultural or social group which may then be impressed upon others. By virtue of observation of an architectural work, an individual may come to understand something about the original builder and his or her culture. Thus, even with no prior intent, architecture by its very nature has a built-in propaganda value [34].

It is common for socialist and communist governments to use architectural propaganda. Examples are Hitler’s Cathedral of Lights, drug cartels use of large houses called mansión narco, and the Moscow Metro. Grand architecture does not automatically make it a propaganda piece but the idea behind socialist architectural propaganda is the unapologetic glorification of the totalitarian state through colossal scale of its structures [2].

Fascist architecture: The fascist style of architecture was similar to the ancient Roman style in that Fascist buildings were generally very large and symmetric with sharp non-rounded edges. The buildings purposefully conveyed a sense of awe and intimidation through their size, and were made of limestone and other durable stones in order to last the entirety of the fascist era. The buildings were also very plain with little or no decoration and lacked any complexity in design.

The fascist style of architecture reflects the values of Fascism as a political ideology that developed in the early 20th century after World War I. The philosophy is defined by a strong nationalist people governed by a totalitarian government. The vision of a strong, unified, and economically stable nation seemed appealing to Western Europe after the physical and economic destruction after World War I, which contributed to the rise of fascism and corporatism.

Fascist architecture was one of many ways for Mussolini to invigorate a cultural rebirth in Italy and to mark a new era of Italian culture under fascism. Similarly, once Hitler came to power in 1933 and transformed the German Chancellery to a dictatorship, he used fascist architecture as one of many tools to help unify and nationalize Germany under his rule (Figure 1) [35].

Dictator architecture: Under a totalitarian regime, the extent of the people’s suffering is often mirrored by the grandiose ambitions of the supreme ruler. Seldom is this clearer than in the architecture. For decades, dictators have tried to outdo each other with building projects breath-taking in their scope. The result has been monuments, landmarks and even entire cities that are ostentatious, overwhelming, and often unnerving to behold.

The dictatorial personality often dislays an obsessive fascination with architecture. Architecture promises compensation for the insufficiencies of worldly power; it offers something concrete. In the 20th century, no dictator worth his salt neglected architecture. Hitler tinkered with his model of Berlin even as the Red Army closed in; Mussolini imagined a second Imperial Rome in ferroconcrete; Saddam Hussein built palaces on the banks of the Tigris. Most of these dreams are now ruins [36]. Defined 10 feature “dictator chic” in their houses as following:- big, old style, lavish curvy style, big public rooms, gold, shiny, color, Decoration, Personal portray and Animals

In 1991 Kim Jong Il, wrote On Architecture, a 170-page treatise detailing the nature and role of architecture in the North Korean state. Much of the content is unsurprising. Stock soundbites from the Marxist-Leninist playbook are sprinkled across every page - architecture must maintain a "revolutionary outlook"; architects must display "party loyalty" and avoid "decadent reactionary bourgeois" design. Architecture, like everything else in the totalitarian state, must be "revolutionary" [37].

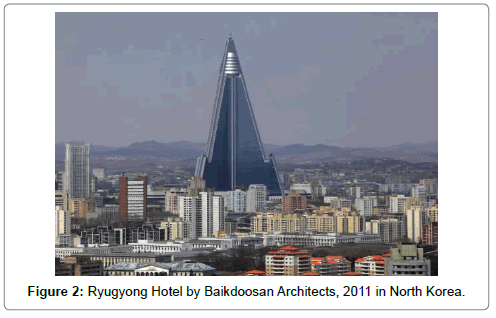

The capital of the state with the worst human rights record on Earth, Pyongyang is architecturally impressive in a terrifying way. Everything is built on a scale so grand it inspires vertigo. The building is also known as the 105 Building, a reference to its number of floors. The building has been planned as a mixed-use development, which would include a hotel. pyramidal Ryugyong Hotel. it has been called the “worst building in the history of mankind” by Esquire, It's the Ryugyong Hotel in North Korea, where the world's 22nd largest skyscraper has been vacant for two decades and is likely to stay that way forever (Figure 2) [38].

The monumental architecture: The world’s political effervescence in in the first decades of 20th century demands from the professionals linked to project and construction a political engagement, which in its turn leads architecture, at certain times or even according to certain characteristics, to be associated with movements, regimes or ideologies of strong social impact.

The architecture, seen as the ideal of representation by rulers linked to authoritarian regimes, and the slogans based on progress and modernization complement this relationship, therefore prompting these governments to invest heavily in the construction of buildings that hallmark, or even represent, their political thinking [14]. However, it is in the official architecture, representative of the authoritarian and dictatorial governments, that these characteristics will find ways to a better development. Countries such as Mexico, Cuba, Argentina, Chile, Uruguay and Brazil all assimilate the model, each of them adding its own regional flavor and thus eliciting enthusiasm from the people, as well as divulging its canons with greater intensity [39].

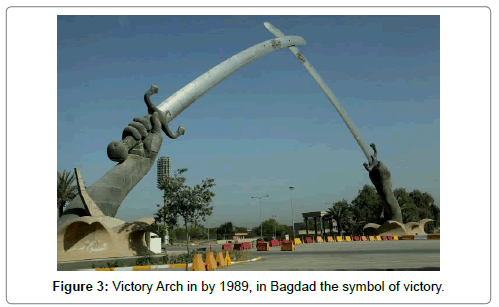

In 1985, President Saddam Hussein enunciated his vision of a victory monument and, four years later, he rode his white stallion under a pair of giant steel arches standing at either end of a huge parade ground in central Baghdad. The Victory Arch, Khalil explains in being not architectural but statuesque. Each archway is formed by two forearms ending in clenched fists grasping swords; the swords cross at the apex, forming a bow 130 feet above the ground. The swords have been built using metal smelted from the armor and weaponry of fallen Iraqi soldiers. Tumbling under nets at the base of each hand are hundreds of helmets, looted from Iranian corpses from the battlefield. Most are cracked and have bullet-holes (Figure 3) [40].

Transparent architecture: The move towards transparency lies at the heart of the federal republic of Germany in the postwar, open public access to political process especially to the elected representatives, active public participation in political system, an open market economic, a free press, and guaranteed civil liberties such as freedom to dissent [41].

Transparency acts as a metaphor in political and architecture discourse, metaphor relate to ideas and language, not things. The relation patterns formed by objects to other objects, and by ideas to objects are called “analogies”. Thus the formal, spatial, and stylistic use of transparency in postwar German architecture is analogical. Although some metaphors can be considered analogies, because they share rational information, the two are different as the authors of the Analogical Mind are careful to point out, “metaphors can be based on common object attributes” while analogies cannot [41].

The use of transparent formal and spatial systems, as well as seethrough materials in west-Germany state architecture is therefore is analogical because it suggests the relationship between physical structure of democratic government and society, and the material and spatial structure of the buildings. The structure of democratic government in this case means a political system open to public observation [41].

Berlin Reichstag building, the project’s meaning is partly drawn from the involvement of public officials and private citizens in its creation. Architects draw on that level of meaning as a matter of a course. It is not only the public use of buildings that makes architecture a social art, it is also the architect’s engagement with clients, communities, contractors and others whose participation is required to alter the material world [30]. Today, Reichstag building is the second most visited places in Germany as Koln church is the first (Figure 4).

Public urban spaces and political changes

Islamic civilizations have created some of the world’s great cities, starting with the religion’s original site of refuge and political organizing, the city of Medina, which the pious make pilgrimages in their millions every year. Public spaces stages for history because they provide the loci for urban gathering, particularly for a city’s youth. One could argue that without cities and the spaces they inspire, nations themselves would never change.

In the Middle East, how urban space, specifically spaces of public assembly, reflects the political priorities of those in power and enhances or prohibits social change. Egypt has reminded us that urban space can drive us towards a changed, perhaps unstable, but in the end better world. While Chinese believe the country should have a oneperson- one-vote democracy, and generally there is a degree of faith in the central government. In the US, we tend to take public spaces and the activities they enable for granted. From the history of protests in Tompkins Square Park, to Martin Luther King’s. The majority of democracies worldwide will continue to see their hopes and pains played out in sweeping public spaces [42].

Architecture Identity in Historical Buildings

Despite the fact that Iraqi Kurdistan has numerous unique historical and heritage sites estimated at 1,307 [43], the Kurds have failed to fully explore its origin in architecture in order to legitimize their national identity and visual image. These historical sites were formulated in different political phases according to the addition of successive regions that had been under distinct occupations for centuries. Such a cultural heterogeneity reveals additional complexity in Kurdish history. “Sharing a common history does not mean that people have shared a common experience of that history” (McNiven, Russell 2005) as cited [44].

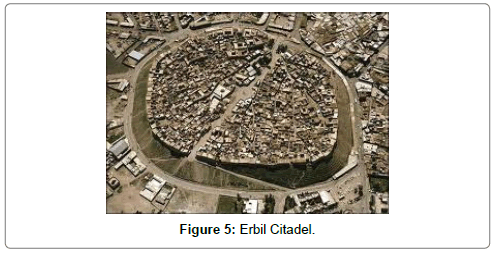

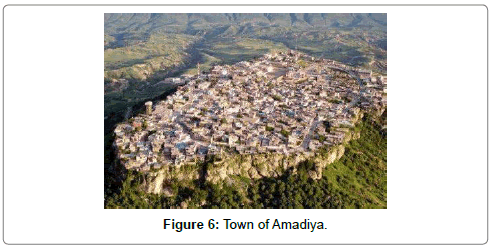

The historical architectural sites in Southern Kurdistan carry a conceptual inconsistency which has arguably resulted in the tensions between the national, regional and the universal at a number of heritage sites since the World Heritage Concept “ignores the strong link between heritage and national identity” (Figures 5 and 6) [3].

Erbil ancient city

Citadel of Erbil (Arbil) is a good example of this old and unique architectural heritage in Kurdistan. Erbil (ancient Arbela) is located in southern Kurdistan, about 360 kilometers north of Baghdad, in Iraq. It is one of the oldest urban sites in the world continuously settled for some 6000 years and has been witness to the rise and fall of major ancient and Islamic cultures as cited [23]. An important stage of Erbil’s’ history was in the 12th century it became part of the Ayyubids Empire which was a Kurdish empire that dominated the Middle East and Egypt for two centuries. Another settlement was built down in the valley beside the hill. The settlement on the hill was divided into three residential areas, Saray at the east, Top Khanah at the south, and Takiyyah at the north. The rich people settled around the edge of the city forming a ring.

This position was popular because it provided views towards the surrounding valley and better ventilation possibilities. Old descriptions of the city done by Yaqut al-Hamawi describes the city during the 12th century as a strong and large city built on the top of a hill and containing houses, markets, and mosques [45].

Amadiya town

Amadiya is a town north west of Iraqi Kurdistan Region. It is about 78 Km north east of Dohuk City. On the Administrative level, Amadiya is a district encompassing five sub districts. Amadiya exists on a huge rocky hill and is about 1640 m above sea level and its area is about 1500 m × 650 m. It is a fort town that goes more than 3000 years back into the history. The town was at some times in the hands of the Assyrians. It became later a main city of the Median State and afterwards the Bahdinan Emirate for six centuries. The town was entered by the Muslims in the 7th century. The town has two ancient gates which are still used. The city has only one access for transportation; originally it has two accesses the second is used by pedestrians now. There are at least six historical remains in the town are poorly reserved [46].

Currently, the ruins of historical sites in Southern Kurdistan function as part of the national evolution under the topic of tourism. In fact, a clear distinction of architectural identity based on Kurdish vocabularies can hardly be perceived since it is fused with the occupied patterns. Although the ruins of these historical sites are of great importance to historians, archaeologists and anthropologists to identify and preserve them as areas of outstanding value to humanity, the question that remains is the role architectural ruins in southern Kurdistan play in forming Kurdish architectural identity. geographically the historical architectural sites are distant from each other those that belong to the same political series share the same political myths and aesthetic characteristics, the aim behind the method is to find Kurdish architectural details (vocabularies) based on the relationship between the morphological structure of the archaeological sites and its political structure [47].

An Attempt to develop a clear definition for the Kurdish architectural identity have reached endless point , due to the problematic of identifying features or elements that give the archaeological sites its visual character, its tangible elements both on the exterior and interior have not been preserved and the available historical evidences are not of help to piece together an overall visual character of the historical sites. In addition to that, the architectural characteristics of the archaeological sites in southern Kurdistan vary depending on the geopolitical dimension and the historical period of each architectural site origin. Therefore its architecture can be classified as the continuity of the colonized architectural identity and thus the visual past in Kurdish region is basically part of its complexity. Lastly, In Southern Kurdistan, the symbolic and aesthetic characteristics of archaeological sites that belonged to particular semi-independent Kurdish principalities are the representations of literally anti-national designs according to the political period of their implementations. According to previous study [48], the selection events of history create a heritage.

Architectural Identity in Kurdistan in 1970-1991

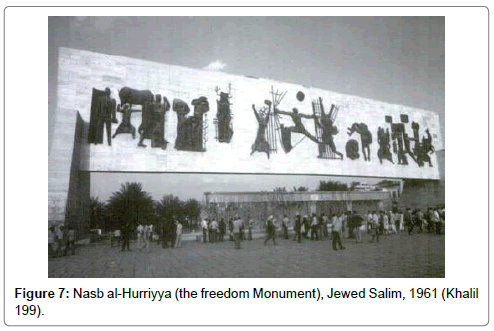

Architectural identity in northern Iraq was produced and legitimized by Iraqi state policies. Following World War I, with the country’s transformation from destruction to construction process since the government funded large infrastructure projects during this period like airports, governmental buildings, cinemas, and many more projects (Ibid). Iraq underwent political transformation processes in 1958 and changed the direction of cultivating modernism in Iraqi architecture quite distinctly to become self-conscious in their anti- Western conceptions [49]. As a result many projects that were led by international architects had been cancelled [50]. In the centre of Baghdad,“public urban space is punctuated with three symbolic monumental carrying a new iconography as a synthesis between the national repertory and a modern style: On Tahrir Square, the bas-relief of Liberty (1961), a Fresco by Faik Hassan (1960); and on Firdaous Square, the monument to the Unknown Soldier, 1959, by Rifat Chardirji, which was explicitly claimed as a symbol of the Iraqi past by referring to the Arch of Ctesiphon, but also implicitly assimilated contemporary references such as arches by Le Corbusier or Niemeyer (Figure 7) [51].

The Baathists adopted the ideology of Baathism, which was based on pan-Arabism, expansionism, and ethnic nationalism; they followed a systematic assimilation, Arabization, and ethnic cleansing policy against the Kurds in the Kurdish territory” [52]. The notion of expressing cultural identity became influential and social phenomena were supported by leading elites during 1960s-70s, [40].

During this period, since administratively the Kurdistan region was part of central Iraqi region, the architectural strategy of the area, proposed by Iraqi policy, which was radically archetypal to the rest of Iraqi provenance in an attempt to maintain a sense of continuity with Iraq and avoiding the socio-cultural characteristics of Kurdish region, which was totally different in all aspects. Moreover, the notion of visualizing Kurdish memory that can threaten Iraqi identity emerged as one of the most influential policies in Iraq and provided the basis for architectural and political strategy of resistance against the architecture as a Kurdish cultural production. However, the lack of sense of Kurdish identity was the dominant characteristic of the architecture in the Kurdish region and it is constantly being refabricated [47].

One of the important decisions by the central authority since 1930’s was reforming and developing the local architecture by adopting international architecture. Yet, the applied plans and architectural solutions had ignored several important issues including that Iraq is composed of different ethnics with different architectural heritages and local needs [23].

On the other hand, many remaining traces, which are expected to be historical sites of Iraqi Kurdistan, have been destroyed in the last century by the Iraqi regimes [53], in an effort to eradicate the Kurdish identity in the built environment. This can be considered obvious evidence showing that architecture is a weapon of which the regimes are aware.

The Kurds, during this period, though lived in restricted areas of the cities or urban areas, and therefore, a Kurdish architect would have a little opportunity to stage an indirect interplay with the built environment of a Kurdish neighborhood. It has been stated [54] that “for an architect, the chief problem with working for a corrupt, oppressive, or dangerous regime is preserving integrity. That problem, though not easy to solve, is not necessarily insoluble”.

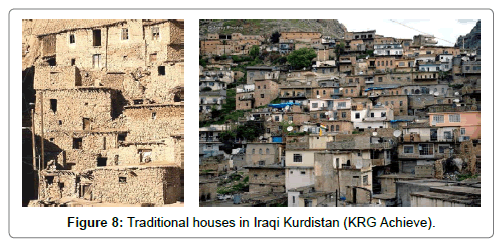

During the mid and late 1970s, the Iraqi regime destroyed around 4,006 Kurdish villages out of the original 4,655 villages and forcibly displaced hundreds of thousands of ethnic Kurds living close to the borders with Iran and Turkey, relocating them in settlements controlled by army [55]. However, the Kurdish villages are a vernacular construction in response to climate of the regions and have an organic interaction with natural environment that have led to construct different patterns of climate-based architecture (Figure 8).

A huge number of neighborhoods were developed at the edge of urban areas of the provinces of (Dohuk, Erbil, and Sulaimania) based on Iraqi principles and depriving the Kurds of cultural, regional and national identity. The most prominent characteristics of such neighborhoods were the dense morphology with minimal access from the outside and the clustering of residential areas. The architecture and planning of repression and replacement reveal plainly the impacts of the elimination of architectural identity as a powerful strategy used by dictatorships to eradicate the identity of a repressed nation.

The most prominent characteristics of the architectural built environment of Southern Kurdistan until the year 1991 was a total reflection of the complex social and political framework that has been the result of the Iraqi state system created after the First World War and the discontinuity of meaning of Kurdish identity and value. The political meaning has a long history of being part of the equation of the built environment and continues right through the present to be a matter for architects and politicians across the world [14].

As a consequence, the architectural heritage of all non-Arabic groups ignored and humiliated. In many cases old cities and built up areas where systematically demolished in order to change its identity. Among these demolishing the old citadel of Kirkuk and relocating hundreds of villages in Kurdistan [23].

Architectural Identity in Kurdistan 1991-2003

Following the 1991 Kurdish exoduses in the Northern Iraq uprising against the regime, a brief period ensured in which semi-autonomy was given to the Kurdish region, with Kurds elected to the state government in 1992 [56]. The Kurdish council of ministries and parliament and other institutions were created by a semi-independent government, at the beginning of Kurdish reconstruction,

Kurdish architectural identity has not been taken as an important component of the development and the advancement of Kurdish culture. This period is considered as an undefined transformation in terms of institutionalizing the new unique form of the built environment of Kurdistan, although, the new political situation provided a great stimulus to accelerate the Kurdish architectural identity, as a recognized medium through which the national value of Kurdish brand (Kurdishness) was to be constructed.

Regional leaders continue embracing the old mode of urban governance, using the same regulations in terms of architectural design and style, despite some of the monumental urbanism aspects having served as propaganda for oppressive Iraqi regimes as ha d been relied on by Napoleon III to Stalin and Mao as “profuse displays of theatricality and excess to uplift and emotionally engage their followers and to legitimize their position as the dominant force in society” [57].

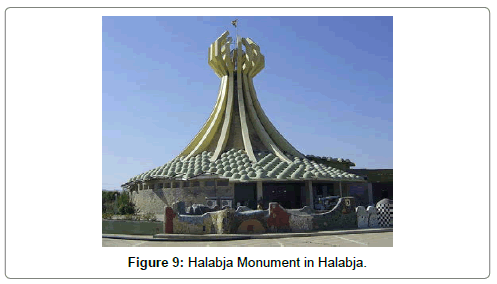

A common theme in these monuments was the Kurdish genocide that served as the myth of the rebirth of the Kurdish nation. Unfortunately, most of these monuments metaphorically represented the essence of Kurdish nation. Thus in terms of expressing the emergence of Kurdish physical memories as a reflection of late twentieth century political changes limited the opportunities to unify the Kurdish society based on cultural references. For example, Halabja Monument of Kurdish Victims of gas massacre 3003 (Figures 9 and 10).

However, on March 16, 2006, the memorial was set on fire, presumably by a thousand of Halabja residents who objected to what they perceived as the lack of sufficient living space and viewed the memorial as a symbol of the government’s persistent inaction, and corruption rather than as a symbol that honors Kurdish tragedy. These debates can be characterized as the contest between political approaches emphasizing an independent society and strategies of resistance versus politics, race, and nationality reflected on the built environment (Figure 11) [58].

Monument of Barzani in Duhok city was constructed in this period adorned by a statue of the leader and the spiritual father of the Kurds, the Immortal Mullah Mustafa Al-Barzani. The main purpose for the park and the statue is to be used to brand the Kurdish identity as been used for ceremonial occasions especially in Nowroz events.

Both monument among many others if, it would represent any of political features it would be corruption and dictatorship. The use of review “monuments as propaganda to unite people under a flag or a statue to present their loyalty leaders have been used in literature Iraq’s most notable tradition was in sculpture” [40].

On another level, during the civil war (1994-1997) between the KDP and PUK, the Kurdish built environment experienced a new phase of urban and architectural change as separate government zones between the two dominant Kurdish political parties. Thus, the architectural production in this period was affiliated to the culture and views of the KDP in Erbil and Dohuk, and to PUK in Sulaymaniyah. The architecture was used to clarify control and power of specific political views that attempted to create challenging realities in one (divided) region space. As stated earlier [59], “Collective identity can equally refer to cities, to regions, or to groups such as political parties or even social movements”.

Within the context of Iraqi Kurdistan, in this period, collective identity referred to political parties rather than a unified region. The weakening of the Kurdish collective identity that has been reconfigured by heterogeneous political concepts controlled architectural planning and development as two different meanings attached to the Kurdish physical form and contributed to construct a sense of political group rather than sense of community and sense of collective identity. The constitution of Kurdish identity in terms of physical space represented complex political meanings and therefore added new challenges to reshape Kurdish national identity (Figure 12).

In addition, Kurdish School of Architecture and Urban Planning (started in 1996) which has to be a focal point had been in its infancy stage of establishment with the first post suppression architects graduated in 2001. The lack of educating Kurdish culture as a base for new design projects to reflect the new phases the region passed through, lack of professional experience among the teaching staff in architectural department on how to deal with the new political situation resulted in problematic skyline that continues today to be on- going issue. Thus, despite the fact that numerous Kurdish architects had gained access to the architecture profession and became directors of urban planning and strategic projects in councils and institutes of the Kurdistan regional environment, the cultural production of two decades is not vital in contributing to the basis of the Kurdistan as the ‘other Iraq’ campaign led by KRG in terms of Kurdish architectural identity.

Architectural Identity in Kurdistan 2003-Present

Politically

Following the Iraqi liberation war and the establishment of an autonomous Kurdistan, The Kurdistan Regional Government makes its own laws, controls its own army and decides its own pace of economic development [43]. On the other hand, since 2006 an economic boom has embarked in Kurdistan due to the oil exploration in addition to, the investment law which permitted allocation of land free of tax for ten years for local, foreign and joint venture investor in several sectors like housing, industry, and truism as main focus for investors. The shared oil revenues have allowed the region to start its reconstruction and development programs much earlier than other regions. That was the result of peaceful situation, economic growth, regional and global changes [60].

The reconstruction of the built environment in Kurdistan has undeniably enjoyed prolonged, rapid growth in many areas of the region during this period. However, it is interesting to note that a high amount of construction of Kurdistan is being done without Kurdish architects, using old adapted projects. In many countries, there is no licensing at all; professionalism itself serves as a license [61].

KRG depends on architectural companies from neighboring countries for most of strategic projects in the region like large-scale governmental buildings, gates, symbols, office buildings, restoration of historical sites, hotels and so on. Understanding the conceptuality of large-scale governmental buildings creates new opportunity to grasp particular aspect of architecture in post semi-independent Iraqi Kurdistan.

Kurdish institutional clients have slipped away from Kurdish architects, opening themselves up to a larger mainstream of international firms. The threat of this strategy, if successful in occupying the region architecturally, would upgrade the opportunity for the region to be segregated more deeply and dependent more realistically on the neighboring countries. In sum, there is no debate that the Kurdish government has certainly stepped forward towards development and reconstruction, with the Kurdish architectural identity in question [47].

Architecturally

The role of architects remained anonymous in reaching toward independence through architectural identity and the physical built environment. In reflecting on the period of suppression in terms of the architectural built environment, it can be concluded that the impact of Kurdish architects in shaping Kurdish identity in architecture to represent a sign of independence among “the architecture of confinement” to act as a form of resistance was invisible. There are a number of common problems that have been linked to the lack of architectural references and architectural identity, which call into question its usefulness as a component of competitiveness, and sustainable national identity. These include foreign domination and dependence on neighboring countries, socioeconomic and spatial loss of national value.

At a turning point in the history of the Kurdish people enjoyed independence since 1991. It is believed that Kurdish independence was a turning point in many ways. However, the political change impacts in architecture had been absent in terms of the loss of collective memories as a main component of social control and identity among communities. Unlike other nations like Israel political change 1948, architecturally, the turning point for Jewish independence is one of the most challenging periods as Israeli architecture has been openly mobilized [62]. It dealt with issues around collective memory, place identity and sense of place by considering the impact of the dialectic of remembering and forgetting the 1948 war on architecture. According to previous study [63] Israeli architecture is considered as a framework differs in intensity (quantity) rather than in essence (quality) from other architectural practices around the world [64].

The dilemma of architecture identity doesn’t accrue only by physical features. But also, by dependency on imported materials rather than developing local materials. One of the reasons real estate is so expensive is due to the economy’s import dependency. There is less predictability in the delivery of imported goods, leading to construction delays. Kurdistan has all the right raw materials,” such as basalt stone (from the mountains), silica sand, and LPG gas, which is produced at crude oil refineries. “The same refineries (and power plants) need lots of insulation. Plus our wool massively reduces energy costs in hot countries like Kurdistan because insulation reduces the work for air conditioners” (Whitcomb, 2014).

Identity as a spirit of the nation, political aim, or the continuity of occupier's identity: The qualitative observation results reveal that the degree of change from the previous periods is very slight in terms of the reflection of Kurdish identity in architecture. The architecture during this period is evidently closer to being thought of as a mere production of the business people and the political elites. The Kurdish identity has seldom been studied through the Kurdish architect's eyes and perspectives. Kurdish identity has always remained invisible in physical design and the Kurdish built environment. In fact, architecture in this context cannot be “color-blind” or culturally neutral [65].

The role of the political system in solidifying architectural identity is distinctive in the governmental building as well as in urban spaces as referred in the literature reviews. the power of architecture is the issue of politicization of spaces at the intersection of the fields of politics, urban planning, art, and architecture, More precisely, the spatial relation of the governmental building to its built (and unbuilt) environment. The selected samples will represent the official buildings that belong to the official government, even though, (some projects sound to be commercial however, the decision belongs to the politics) for the three governorates in Kurdistan. The focus will in Erbil city not only for being the capital of the Kurdistan region in Iraq, But also, due to the historical value of the city for being the main source for Kurdish architectural identity which is recognized by UNESCO as world heritage site since 2014.

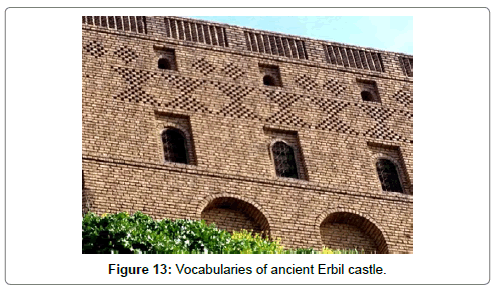

Erbil governorate building

The building has been designed in the Erbil Castle Revival style, which emulated classical Ottoman architecture fused with international style. Although the external architecture of the Erbil new governorate building has been designed to reflect the purpose of the building and to forge the spirit and idea of city identity, searching for a contemporaneous Kurdish architecture and the importance of understanding the value of Kurdish identity in architecture can hardly be perceived. The design of the architectural vocabularies borrowed from ancient Erbil Castle has been fused with the international pattern [60]. This is an example of the post semi-independence architecture and reflects the absence of a sense of independence in architecture. On one hand, political elites have played a crucial role in the formation of this architectural confusion towards both a Kurdish national style and international modernism (Figures 13 and 14).

Residential projects

Since architects has the opportunity “to work more effectively as social reformers and political mediators” [66]. In Iraqi Kurdistan, the visual identity is simply an ill-fitting import from outside and most architectural projects are primarily intended as money-making projects (Figures 15 and 16).

For nations with limited recognition like the Kurds who have struggled towards recognition, using most amicable and non-amicable ways, and have not reached its aim yet, it is possible to view the lack of Kurdish identity in architecture as a relative factor, which potentially has affected such phenomena. Since the relationship between nation image and national identity is longitudinal, an abstraction of both culture and politics [67]. Additionally, as [68] indicates that “country’s image is a reflection, sometimes distorted, of its fundamental being, a measure of its health, and a mirror to its soul” (Figures 17 and 18).

Kurdistan is encountering the physical colonization of the built environment. For example, these projects, which began appearing on the Kurdish scope after the second half of the 2000s, are examples of the aforementioned pluralism in Kurdistan [69-72].

Although developers have already completed work on several projects, the most of these projects lack cultural references and dimensions [73-78]. Actually, the image that Kurdish ruling elites are trying to build is “Kurdistan is another Iraq”. Kurdish political skyline is inversed to the Kurdish physical skyline in terms of basic mechanism of their struggling toward independency and achieving national identity.

Politically, the Kurdish nation is struggling for the liberation of its terrain from neighboring countries occupation. Architecturally, the Kurdish ruling elites offer international companies from the neighboring countries to occupy the region physically by constructing massive and strategic projects, which represent Kurdistan sovereignty with their own architectural identity.

There are great attempts by neighboring countries in particular Turkey to affiliate the region physically through architecture under the pretext of taking part in the process of reconstruction the region and under the economic dimensions of foreign direct investment (FDI) which, is sponsored by Kurdish leading elites [79-82].

Conclusion

Studying architectural identity of different nations through history can provide us with important lessons that can be useful to develop the general knowledge of architecture and practice that make architectural identity a free human right for all nations on this planet. Historical events show that changing the traditional architecture to the modern architecture has been influenced directly by the elites and less by the architecture and local identity. There are no symbolic and aesthetic vocabularies identified to be the main source of inspiration for Kurdish nation. The anarchy use of symbolic element came to be seen as a key in the construction process of some buildings.

The discrimination and the repression practiced by previous regimes helped to explain the marginalization of Kurdish architectural vocabularies and its role in Kurdish identity. However, for the time being fully independent since 1991 it is a kind of hard task to explore the policies that have been approached by quasi- Kurdish government continuing to marginalize efforts to define Kurdish architectural identity. The Kurdish architect professionally experiences the same conspiracy of marginalization by the current government.

It can be concluded that the impact of political system in kurdistan in conserving architectural identity was repressive; in addition to that, the political system diminished Kurdish identity by invading it with the physical elements from foreign countries. In most societies, political changes lead to physical and environmental change. Whither these changes are negative or positive (those represent the leaders). However, in Kurdistan case; following the turning point in the history of Kurds in 1991, the only change is in the wealth of the politics and their allies. Since our cities are lack of basic infrastructure elements etc. electricity, water streets, social welfare and ext. unless a real democratic system developed in Kurdistan, there will be no architectural identity. Continuous ignorance to the Kurdish architectural identity by Kurdish ruling elites and architects has resulted in the current isolation and partisan division of all parts of semi –independent Kurdistan and affected an overall sense of collective identity.

The political impact in shaping architectural identity is undeniable truth. It can be concluded from the study of a literature review that a physical element can perceive the policy-maker’s perception and ambitious. It could be concluded that open policies lead to more identified societies while corrupted governments result in conspiracy.

The radical global changes in many countries including the recent Arabic countries raise the necessity of changing the old established thinking and practice about architectural identity. It will require making architecture a real reflection of people’s culture, needs, and participation. We need adopt new ways of architectural education and practice that will consider the multiethnic realities and will adopt democratic and open decision-making process.

The concept of sustainability can be noticed in the absence of the role of Kurdish architects as cultural producers. The architecture during this period is evidently closer to being thought of as a mere production of the business people and the political elites. During this process, present architectural identity has shifted its meaning from being a reflection of the local milieu to abstract reflections of distinct movements using lines, colors, materials, shapes, forms, and masses as elements to achieve their particular architectural identity. As a consequence, a large number of cities in the world have been transformed into scenes of crowded architectural identities.

The Kurdistan parliament building closed for approximately two years while, the Reichstag building in Germany is the second most visited place in Germany in addition to parliament sessions watched by people with pre-online registration. Democracy and dictator can be perceived by the function of building.

The awareness of architecture’s role in managing our precious natural resources and the responsibility to design the built environment with efficient energy use and conservation in mind are now universal.

Recommendations

The study aims at raising awareness of the value of the cultural heritage on a local scale, and on the other hand, to elaborate negotiation on the cultural heterogeneity in a wider context.

Archaeological site analysis is the necessary starting investigation tool to approach the problem of defining the characteristic of Kurdish identity in architecture in its politicized historical context.

The architectural discipline in the Kurdish region needs a revolution and reconstructing to free Kurdish architects' role from being hidden and anonymous, to reflect positively on the recognition of Kurdish entity and the visibility of Kurdish identity.

The sustained efforts and commitment of professionals and decision makers toward the creation of Kurdish architectural identity can play a key role in the continuation of the sustained and competitive Kurdish identity.

Politicians and architects together can provide visible brand recognition to the Kurdish nation serves as arch-graphical border and can be the national icon of Kurdish history offering “great value” for the Kurds as architecture.

Sustainable local architecture has been widely introduced as criteria in design competitions, both in building project contests as well as for new urban development plans, promoting innovative solutions that integrate architectural design with cultural.

The study through these policies seeks to promote awareness and understanding of the contribution of Kurdish architecture value to the sustainability of the Kurdish national identity. To achieve the national stability, the policy establishes action to construct architecture as a spirit of Kurdish nation shared between Kurdish provinces and areas. The most prominent characteristics of the built environment of Southern Kurdistan will be a total reflection of the complex social and political framework that result from the Kurdish national system and can be realized within the timeframe of the policy and thus, we have to work in several directions to achieve nation architectural identity by working in the following fields:

• Conservation and maintenance of the architectural heritage buildings.

• Build a bridge between architecture and public policy.

• Legislation, guidelines to maintain architectural identity.

• Introduce prizes with architectural identity as criteria in design competitions.

• Inventories of the architectural heritage in all municipalities.

• Web sites dedicated to promoting local architecture.

• Raising public awareness about architectural identity.

• Research on a structural relationship between certain architectural realizations and a democratic consciousness.

References

- Roth LM (1994) Understanding Architecture: Its Elements, History and Meaning. London: Herbert Press.

- Satterfield D (2017) Architectural Propaganda & Leadership. The leader maker.

- Rakic DC (2007) World heritage: exploring the tension between the universal and the national. Journal of Heritage Tourism 145-155.

- Gehry F (2013) What Is ‘Architectural Identity’? Part I. Retrieved from designstudioarchitects.

- Abrams H (1988) Social Identifications: A Social Psychology of Intergroup. London: Routledge.

- Ozaki R (2005) House Design as a Representation Of Values And Lifestyles. England Ashgate Publishing.

- Correa C (1983) Quest for Identity, Exploring Architecture in Islamic Cultures.

- Torab Z (2013) Effective Factors in Shaping the Identity of Architecture. Middle-East Journal of Scientific Research 106-113.

- Peterkova J (2003) European Cultural Identity: The Role of Cultural Heritage in the Process of Mutual Communication and Creation of Consciousness of Common Cultural Identity. European Cultural Identity.

- Hall S (1996) Who Needs Identity? Questions of Cultural Identity. London: Sage. 1-17.

- Tomić DV (2002) Negotiating Cultural Identity through the Architectural Representation Case Study: Foreign Embassy in Belgrade. Architecture and Civil Engineering 113-124.

- Stets JE, Burke PJ (2000) Identity Theory and Social Identity Theory. Social Psychology Quarterly 224-237.

- Abel C, Foster N (2000) Architecture and Identity, responses to culture and technological change. London & New Yourk: Routledge.

- Vale LJ (1992) Architecture power and national identity. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Ghotbi AA (2008) The concept of identity and modern Iranian architecture. Aeiine Khial Journal 10.

- Herrle P, Wegerhoff E (2008). Architecture and Identity. Münster: LIT Verlag Münster.

- Carmen P (2006) Identity, National Identities, Space, Time: Identity pp. 189-206.

- Yasin S (2011) Influence of Modernity versus Continuity of Architectural Identity on House Facade in Erbil City Iraq. Universiti Sains Malaysia.

- Gür E (2007) A Comparative Space Identification Elements Analysis Method for Districts: Maslak & Levent Istanbul. 6th International Space Syntax Symposium.

- Lynch K (1960) The Image of the City Cambridge: Massachusetts MIT Press.

- Tran J (2013) Static Illusions: Architectural Identity Meaning and History. Humanities Graduate Research Conference Curtin University.

- Elkadi H (2005) Glass and Meaningful Place-Making. Journal of Urban Technology 12: 89-106.

- Nooraddin H (2012) Architectural Identity in an Era of Change. Developing Country Studies: 81-96.

- Nnamdi E (2002) Architecture and power in Africa New York. Praeger Publisher.

- Braunfels W (1988) Urban design in Western Europe: Regime and architecture: University of Chicago Press.

- Minkenberg M (2014) Power and Architecture: The Construction of Capitals and the Politic Space New York. Berghahn Books.

- Polo AZ (2008) The Politics of the Envelope. A Political Critique of Materialism 17: 76-105.

- Kulkarni R (2011) Effect of Politics on Architecture. A Simplified History of Architecture.

- Swett R (2000) Design Diplomacy: Architecture's Relationship With Public Policy. DesignIntelligence.

- Castillo G (2010) Cold War on the Home Front. The Soft Power of Midcentury Design Minneapolis University Of Minnesota Press.

- Safa FA (1998) The Finnish Architectural Policy. Arts Council of Finland and Ministry of Education.

- Wikipedia (2017) Architectural Propaganda. Wikipedia the free Encyclopedia.

- Romana C (2009) The Fascinating World of Fascist Architecture. Casa Romana.

- Baker B (2015) Donald Trump has the Design Taste of a Dictator. Politico Magazine.

- Coelho MD (1993) The city's architecture as representation of power. 15th International planning history society conference Brazil.

- Khalil S (1991) The monument : art, vulgarity, and responsibility in Iraq. London.

- Barnstone DA (2005) The Transparent State: Architecture and Politics in Postwar Germany. Routledge London and New York.

- KRG (2008) The Kurdistan region: Invest in the future. Kurdistan Regional Government.

- Ebrary RH (2008) Archaeology as political action. University of California Press Berkeley.

- Ismail S (2006) Stimulating the potential of historic-centers and brown fields within a local context. Sustainable and Integrated Urban renewa Amman University of Dohuk 1: 173.

- Ebraheem S (2013) The impact of architectural identity on nation branding: the case study of iraqi kurdistan. Manchester Metropolitan University.

- Lowenthal D (1985) Past is a Foreign Country. Cambridge University Press.

- Pyla P (2008) Back to the Future: Doxiadis's Plans for Baghdad. journal of Planning History SAGE Publications.

- Mehdi S (2008) Modernism in Baghdad. College of Arts Amman University Jordan.

- Pieri C (2008) Modernity and its Posts in Constructing an Arab Capital: Baghdad's Urban Space and Architecture. Middle East Studies Association Bulletin 32-39.

- CHAK (2007) Anfal: The Iraqi State’s Genocide Against the Kurds. 1-84.

- Romano D (2004) Safe havens as political projects, The case of Iraqi Kurdistan. New York: Palgrave Macmillan Ltd.

- Clwyd A (2007) A Triumph of Determination. Invest in the Future pp. 4-63.

- Broudehoux A (2010) Images of power: Architectures of the integrated spectacle at the Beijing Olympics. Journal of Architectural Education 52-62.

- Amin MH (2003) Il monumento in memoria delle vittime dell'attacco di Halabja. Governo Regionale del Kurdistan Rappresentanza in Italia.

- Eder K (2009) A Theory of Collective Identity Making Sense of the Debate on a European Identity. European Journal of Social Theory 427-447.

- Hassan SY (2010) The Influence of Modernity on Kurdish Architectural Identity. American J. of Engineering and Applied Sciences 552-559.

- Leach N (1999) Architecture and revolution: contemporary perspectives on Central and Eastern Europe. London, Routledge.

- Rieniets PM (2006) City of collision: Jerusalem and the principles of conflict urbanism. Basel: Boston Birkhäuser.

- LeVine SM (2007) Reapproaching borders: New perspectives on the study of Israel-Palestine. Lanham: Md Plymouth, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Segal R (2003) A civilian occupation: The politics of Israeli architecture. Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv, Babel.

- Mann TA (1996) Reconstructing architecture: critical discourses and social practices London. University of Minnesota Press.

- Charlesworth ER (2006) Architects without frontiers: war, reconstruction and design responsibility. Amestrdam London Architectural.

- Kubacki HK (2007) Unravelling the complex relationship between nationhood, national and cultural identity and place branding. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy 305-3016.

- Simonin B (2008) Nation branding and public diplomacy: Challenges and opportunities. The Fletcher Forum of World Affairs, pp: 19-34.

- Adam R (2012) The Role of Place Identity in the Perception, Understanding, and Design of Built Environments. Portugal.

- Hernan Casakin FB (2013) The Role of Place Identity in the Perception, Understanding, and Design of Built Environments. Bentham Science Publishers Purtugal.

- Holland JH (1996) Hidden order: how adaptation builds complexity. Scientific American Incorporated New York.

- Japha V (1991) Identity through detail: Architecture and Cultural Aspiration in montagu. South Africa T0SR 2: 17-33.

- Kajtazi TJ (2014) Architecture as Political Expression. Thesis 2: 139-160.

- Kralova KP (2007) Photogrammetric Documentation and Visualization of Choli Minaret and Great Citadel In Erbil/Iraq.

- Mcmanus D (2013) Iraqi Parliament Development - Design by Assemblage Architects. E-Architect.

- McNeill J (2003) Architecture banal nationalism and re-territorialization. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 738-748.

- Saliya Y (1986) Notes on Architectural Identity in the Cultural Context. The School of Architecture, Institut Teknologi Bandung and partner with the Indonesian.

- Sarup M (1996) Identity, culture and the Postmodern world. Edinburgh University Press.

- Team M (2011) New U.S. Embassy in London. Morphosis Architecture Planning Tangents Research news.

- Woodward K (1997) Concepts of Identity and Difference. London: Sage Publications.

Citation: Othman HA (2018) Architectural Identity Shaped by the Political System, Kurdistan Region Since 1991 as a Case Study. J Archit Eng Tech 7: 216. DOI: 10.4172/2168-9717.1000216

Copyright: © 2018 Othman HA. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 7632

- [From(publication date): 0-2018 - Nov 21, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 6604

- PDF downloads: 1028