Research Article Open Access

Associating Liver Partition and Portal Vein Ligation for Staged Hepatectomy: A Contemporary Surgical Oncology Conundrum

Peteja M1,2, Pelikan A1,2,4*, Vavra P1,2, Lerch M1,2, Ihnat P1,2, Zonca P1,2 and Janout V3

1Surgery Clinic, University Hospital Ostrava, Czech Republic

2Department of Surgical Studies, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ostrava, Czech Republic

3Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ostrava, Czech Republic

4St. Mary‘s Hospital Newport Isle of Wight, UK

- *Corresponding Author:

- Prof. Anton Pelikán MD DSC

University Hospital Ostrava, 17. listopadu 1790

70800 Ostrava, Czech Republic

Tel: 420 59 737 5052

E-mail: anton.pelikan@fno.cz

Received date: May 05, 2015; Accepted date: June 06, 2015; Published date: June 14, 2015

Citation: Peteja M, Pelikan A, Vavra P, Lerch M, Ihnat P, et al. (2015) Associating Liver Partition and Portal Vein Ligation for Staged Hepatectomy: A Contemporary Surgical Oncology Conundrum. J Gastrointest Dig Syst 5:296. doi:10.4172/2161-069X.1000296

Copyright: © 2015 Peteja M, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License; which permits unrestricted use; distribution; and reproduction in any medium; provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Gastrointestinal & Digestive System

Abstract

Aim: The aim of this paper is ongoing evaluation of the Associating Partition Liver and Portal Vein Ligation for Staged Hepatectomy (ALPPS) and present changes in the perception of the use of this method. This paper also includes the case history of the first patient who underwent the operation at the authors' department.

Material and method: A systematic literature review: PubMed database for keywords ALPPS or stage liver resection. The primary aim of the study was to evaluate the potential of this method leading to hypertrophy of liver tissue. Secondary aims included the analysis of morbidity and mortality and the evaluation of technical aspects.

Results: After entering the keywords into the PubMed database, having regard to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, several cohort studies were identified. No prospective randomized study was found. By analysing the results of individual papers we found that hypertrophy of the liver parenchyma ranged from 61% to 93%. Morbidity of the published populations ranged from 9% to 71%, with mortality from 0% to 13%.

Conclusion: Given the high morbidity and mortality, ALPPS is the most discussed modality in hepatobiliary surgery as well as in general surgery. Despite the not-so-flattering results achieved so far, the authors believe that this method has its place in the hepatobiliary surgery to treat liver tumours. However, long-term results are not yet available.

Abstract

Aim: The aim of this paper is ongoing evaluation of the Associating Partition Liver and Portal Vein Ligation for Staged Hepatectomy (ALPPS) and present changes in the perception of the use of this method. This paper also includes the case history of the first patient who underwent the operation at the authors' department.

Material and method: A systematic literature review: PubMed database for keywords ALPPS or stage liver resection. The primary aim of the study was to evaluate the potential of this method leading to hypertrophy of liver tissue. Secondary aims included the analysis of morbidity and mortality and the evaluation of technical aspects.

Results: After entering the keywords into the PubMed database, having regard to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, several cohort studies were identified. No prospective randomized study was found. By analysing the results of individual papers we found that hypertrophy of the liver parenchyma ranged from 61% to 93%. Morbidity of the published populations ranged from 9% to 71%, with mortality from 0% to 13%.

Conclusion: Given the high morbidity and mortality, ALPPS is the most discussed modality in hepatobiliary surgery as well as in general surgery. Despite the not-so-flattering results achieved so far, the authors believe that this method has its place in the hepatobiliary surgery to treat liver tumours. However, long-term results are not yet available.

Keywords

ALPPS; Hepatic hypertrophy; Portal vein ligation; Liver resection; Multiple liver metastases

Abbreviations

PVE: Portal Vein Embolization; PVL: Portal Vein Ligation; ALPPS: Associating Liver Partition and Portal Vein Ligation for Staged Hepatectomy; FLR: Functional Liver Capacity; TLV: Total Liver Volume; KGR: Kinetic Growth Rate; BW: Body Weight; HCC: Hepatocelular Cancer; CCC: Cholangiocelular Cancer; NET: Neuroendocrine Tumor; CRLM: Colorectal Liver Metastasis; GBC: Gallbladder Cancer; USG: Ultrasonography

Introduction

Not so long ago, liver metastases were considered a sign of inoperability of the primary focus. Liver surgery as we know it today dates back to 1967, when Flanagan and Foster first performed a resection of liver metastases. Another significant milestone came at the beginning of the 1980s with the creation of anatomical resection nomenclature and the introduction of intraoperative ultrasound liver scan (Bismuth and Makuuhi) [1]. At that time, Makuuchi et al. performed the first portal vein embolisation (PVE) with the aim to induce compensatory hypertrophy of the contralateral liver lobe in order to allow the resection of multiple metastatic lesions [2]. Roughly a decade later, Adam et al. introduced the two:stage liver resection associated with their regeneration/hypertrophy in the interval between the individual operation steps [3]. Soon thereafter, Jaeck et al. combined the embolisation of the right portal vein branch with the removal of the foci from the left lobe [4]. This approach became the basis for a new strategy combining right PVE with a non:anatomical resection of the left liver lobe [2,5]. The method is currently recommended as the “gold standard” in the case of insufficient FLR; however, it has one serious handicap. Hypertrophy of the liver parenchyma will require a long period of time of up to 8 weeks, during which we can often witness relapses, or tumour progression, which prevents the second resection stage in 19:33% of patients. Another reason for failure is insufficient FLR hypertrophy [6-10]. Abulkhir et al. worked on one of the largest populations, observing 1,088 patients with PVE and finding a 15% failure rate [6,7]. At that time, it became obvious that important factors of liver lesion resectability do not include only the volume of unremoved tissue, but also its quality, which is crucial for functionality. Two:stage resection technique, where the first stage consists in the ligation of the portal branch in the more affected liver lobe and in simultaneous liver splitting, was first described by Schlitt in Regensburg [5,11,12]. It seems that this method, called ALPPS (Associating Liver Partition and Portal Vein Ligation for Staged Hepatectomy) has the potential to offer hope to patients with hepatic tumour which cannot be resected according to the current criteria, as well as to patients after the failure of previous modalities, such as the PVE or PVL. It is a new method, so far with very limited statistical results given the short time period and small populations.

Material and Methodology

When compiling a summary report, we relied on PubMed and Medline an electronic database which, after entering the key words “ALPPS” and “stage liver resection”, “portal vein ligation”, “liver hypertrophy” and “liver metastatic disease” produced a set of papers dealing with this issue. In the data analysis, we excluded individual case histories and only assessed comprehensive patient populations.

Indication and Contraindication

ALPPS indication is a patient with borderline operable/inoperable locally advanced multiple liver tumour of varying etiology, whose FLR/TLV (future liver remnant/total liver volume) index is less than 25:30% for healthy tissue, or 40% for unhealthy liver [5,8-10,13]. After the initial enthusiasm about the suitability of this method for all types of tumours and the majority of patients, we are experiencing the onset of reality where it is time to evaluate indication criteria. In terms of its very nature, we can indicate metastases of colorectal carcinoma, breast carcinoma, Klatskin tumour, gallbladder carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) or neuroendocrine tumour [5,6]. However, past experience shows the best prognosis for patients with metastasis of colorectal carcinoma (mCRC) and patients in the under 60 age group. The ideal combination is a mCRC patient younger than 60 years of age. (Contraindications mainly consist in locally inoperable metastases in the lobe, which should remain after the completion of the second stage resection, inoperable extrahepatic metastases, severe portal hypertension, inoperable primary tumour, high anesthesiology risk together with serious co:morbidities and the impossibility to achieve R0 resection [5,8,14]. There is still ambiguity regarding cholestasis and biliary drainage. Some authors argue that patients after biliary drainage with liver cholestasis and reduced regenerative capacity are contraindicated for ALPPS due to a disproportionately increased risk of bacteremia, which, as evidenced by experience, shows almost no response to antibiotic treatment [5,14]. The indication criteria undergo continuous detailed evaluation based on the experience of various departments in order to select a group of patients for whom this method is beneficial [8-10,15-17].

Preoperative Preparation

Preoperative patient preparation is carried out according to a standard procedure of each liver surgery centre for liver resections. It is necessary to consider both cardiac, as well as respiratory and nefrology risks, the latter not being an absolute contraindication to the operation. In addition to standard laboratory tests, we also test tumour markers: AFP, CEA, CA 19-9. PET-CT is not yet habitually recommended, but should be performed (in addition to primary HCC diagnosis) to exclude extrahepatic metastases [18].

Volumometry and evaluation of the functional liver capacity/FLR/

The specificities of liver surgery obviously include volumometric FLR evaluation and mainly the evaluation of the functional liver parenchyma reserve. In addition to absolute measuring of the FLR and its percentage in relation to the total liver volume, we must also calculate the absolute or relative increase in the volume per day (KGR: kinetic growth rate) [10,19]. Naturally, these methods only provide information about the volume rather than about the regenerative capacity of the liver parenchyma. Unfortunately, most tests evaluate the function of the entire parenchyma, without the FLR specificity [9]. Some authors recommend that a functional intraoperative evaluation using clearance indocyan green be performed [20]. However, so far there has been no unambiguous diagnostic modality to safely evaluate the functional FLR capacity before an extensive liver resection.

Technical ALPPS Aspects and Modification of the Original Operation Procedure

Original operation procedure

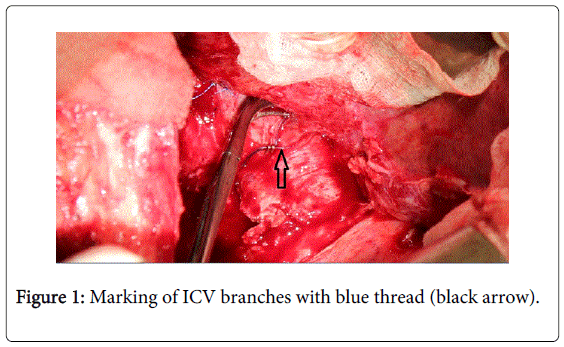

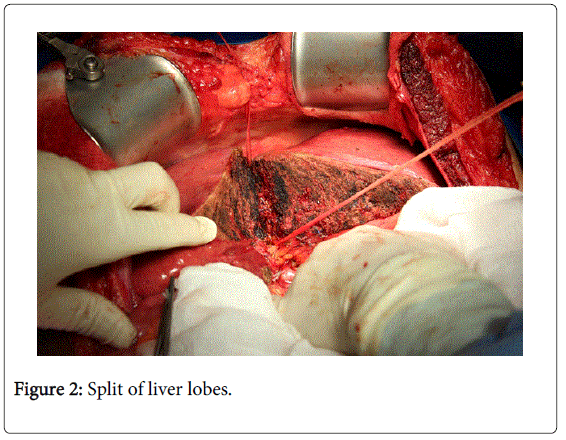

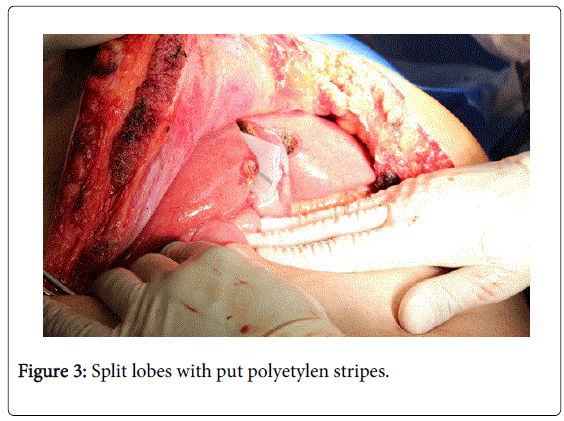

Stage 1: After initial postoperative USG, the operation continues either by performing cholecystectomy [6] or radical lymphadenectomy of the hepatoduodenal ligament and the a. hepatica communis area [5]. Lymphadenectomy is performed both for oncological reasons, and also to clarify anatomical relationships. After fully mobilizing the right liver lobe, the next step is to ligate and interrupt the portal branch for the right lobe and the first segment. Retrohepatic venous connection to v. cava inferior are also ligated and interrupted. Hepatic veins, arteries and bile ducts must be marked with coloured curtains for easier identification in the second stage (Figure 1) [5,6]. During preparation in the liver hilus, it is crucial to avoid injury to the arterial blood supply for the lobe intended for later removal, because after ligatig the portal branch, the artery is the sole source of nutrition and oxygen supply and, as a result, its injury can lead to the necrosis of the entire lobe [6]. The next step is a complete or almost complete liver splitting [9]. The resection line is the right side of ligamentum falciforme. Splitting is performed to the level of inferior vena cava (Figure 2). Most commonly, an ultrasonic dissector (CUSA) is used in combination with coagulation, argon-plasma coagulation or ultrasound (harmonic) scalpel. It is also possible to use WaterJet dissection or bipolar LigaSure:type coagulation [5,6]. It is generally considered that the experience of the surgeon is more important than the type of instrument used [21]. The following step is metastasectomy of the “future liver remnant”: after this stage, some departments insert the removed part of the liver into a bag, to which they insert a drain and tie it. Others only apply polyethylene tapes to the resection line (Figure 3). The bag has an advantage in that it prevents the formation of adhesions and, moreover, in the second stage it can be removed together with the secretion. The disadvantage consists in the fact that it is a foreign material, which creates a predisposition for bacterial colonization [5]. At the end of the first stage, it is advisable to carry out ultrasonic test of portal branches, because in a certain number of cases the rear portal branch is so large that it can imitate the real portal vein. If left unligated, the hypertrophy process would fail. Finally, a leak test of the biliary tree is performed in the resection line by means of a cannula introduced into cystic duct [5,6,8,14]. Drains are inserted into the right subhepatic space and into the liver resection line area [5,6,14]. Several facts are important in terms of the development of technical aspects. During the first stage, it is essential to avoid injury to the right hepatic artery and the bile duct. Although bile duct injury does not lead to hypertrophy failure, it significantly increases the morbidity and mortality of the operation [22]. Another important aspect is the use of a plastic cover of the parenchyma being split. A number of departments use it as a prevention of adhesions, while others reject it due to the potential impossibility to perform second stage with the ensuing problem of foreign material left in the peritoneal cavity, which must be removed.

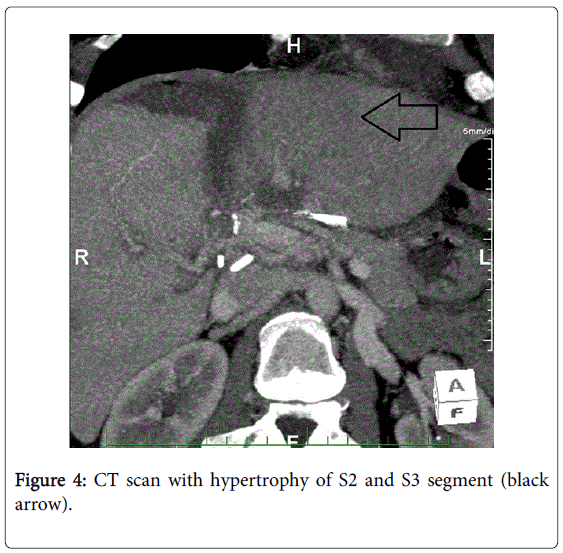

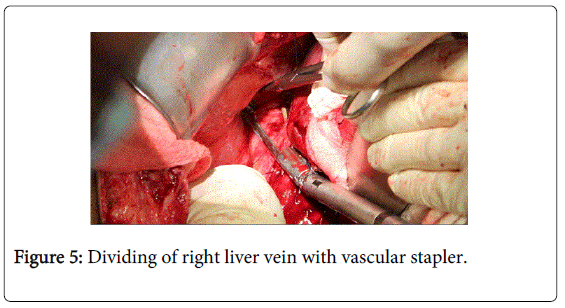

Stage 2: Given the risk of bacterial infection, foreign material in the abdominal cavity as well as ischemic tissue, ATB administration is indicated for the entire time between the first and second stages of the operation. For the second stage, most authors prefer a combination of parenteral and enteral nutrition. After the second stage, they prefer only enteral nutrition as prevention of metabolic liver remnant overload [5]. On the 6th to 7th day after the second stage, volumometry is performed by means of computer tomography or magnetic resonance imaging. If the desired degree of hypertrophy is achieved and the condition of the patient is good, the next step follows (Figure 4). The abdominal cavity is penetrated using the same procedure as in the previous operation. It is advisable to take bacterial swabs. Due to a certain change in the anatomical situation (increasing liver remnant can lead to a non-standard dislocation of other structures), caution should be exercised in the preparation [3]. The affected lobe is removed in its entirety, while most authors recommend that vascular and biliary structures be interrupted with vascular staplers (Figure 5). After removing the lobe, drains are inserted into the same positions as in the first stage-the right space below diaphragm and the resection line area [5,6].

Modification of the original technique

Hepatoduodenal ligament dissection.

At the very beginnings of the ALPPS technique, the majority of publications described a routine dissection of the hepatodudenal ligament both for oncologic radicality, but mainly to improve the identification of the individual structures and to reduce the risk of injury to the bile duct or an artery [9,12,23]. Conversely, other authors warn of an extensive dissection of the ligament due to an increased risk of segment S4 ischaemia and the related complications increasing morbidity and mortality [24].

• In 2013, Gauzolino et al. described three technical variants of the original ALPPS technique.

• Left ALPPS, which consists in ligating the left portal vein and splitting along the main portal fissure line.

• Rescue ALPPS. This is the splitting along the main portal fissure following previous radiological PVE with insufficient hypertrophy; therefore, classical resection cannot be indicated for the patient.

• Right ALPPS. The first stage involves left lateral sectionectomy followed by ligation of the posterolateral branch of the right portal vein with anatomical resection of S5, S8 and caudate lobe [25].

Other ALPPS modifications include RALPP technique, presented by authors from the UK. It consists in portal branch ligation and RFA of the demarcation line instead of splitting [26].

A very interesting technique was presented by Robles et al. in 2013: ALTPS (Associating Liver Tourniquet and Portal Ligation for Staged Hepatectomy). After ligating the portal branch, instead of splitting they used Vicryl ligation in the form of a tourniquet inserted either in Rex:Cantlie line or to the right of ligamentum falciforme. The aforementioned method shortens the operating time of the first stage and decreases morbidity given the simplicity of the invasion in the parenchyma [27].

In addition to the aforementioned techniques, it is necessary to mention the successful laparoscopy ALPPS operation, which reduces the risk of massive adhesions after the first stage. At the very beginnings, laparoscopy was performed only in the first stage, but recently studies dealing with a complete ALPPS laparoscopic procedures have been published [28-30].

The last variant described is monosegmental ALPPS modification, which is defined as an extensive hepatic resection leaving one segment or without S1. Despite a potential division into A and B, segment IV is considered as one [31].

Results

The number of patients who underwent ALPPS reaches a couple hundred cases worldwide. The largest population is that of Schnitzbauer, who aggregated patients from five major German facilities. Regensburg, Tübingen, Mainz, Göttingen and Giessen [12,32], and also that of Clavien of Zurich [2,8] and finally that of de Santibanes of Buenos Aires [2,5,11,33]. The population of Schnitzbauer was the first comprehensive group of patients who underwent ALPPS operations. There were 25 patients, of whom 9 patients with primary liver malignancy (hepatocellular carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma, gallbladder carcinoma, malignant hemangioendothelioma) and 16 patients with secondary, metastatic tumour (colorectal cancer, ovarian cancer and gastric cancer). The preoperative FLR volume fluctuated between 192 to 444 ml (average of 310 ml) and after an average of 9 days (5:28) there was an increase in the volume to 536 ml (273:881 ml), i.e. an increase of 73% (21-192%). Postoperative morbidity stood at 68% and hospital mortality at 12% [12]. The population of de Santibanes consisted of 15 patients who underwent ALPPS. Again, a volume growth of 78.4% is reported, with morbidity at 53% and mortality at 0% [5]. Recently, other populations presented were those of Torres et al., Brasil, consisting of 39 patients [34], Jun Lia, Germany, consisting of 9 patients, and Knoefel, Germany, consisting of 7 patients [6,14]. Proportion of patients files with various tumor types are in Table 1. Preoperative and postoperative values FLR, FLR/TLV, and the percentage increase in volume are in Table 2. The important aspect is a feasibility of ALPPS methods. In the examined files the feasibility of both phases ranged from 95:100% after reaching R0 resection in 86-100% [9]. Oncological viewpoint is yet difficult assessable because the results of recurrence fluctuate between 5-87%. This is probably due to a statistical error of small files and small populations with short follow up period than was initially an inappropriate surgical method. Unfortunately, this inhomogeneous files and long term results are missing, because the method is not used very short time. This inhomogeneous files and long term results are missing unfortunately, because the method is used very short time till now [35].

Our Own Case Report

The first patient, who underwent ALPPS procedure in our Surgery, was a 51 years old man, with the second type of diabetes on insulin therapy and with higher blood pressure too. He underwent laparoscopic sigmoid resection/01/13/: p. histology adenocarcinoma G1T3N1 (26/3) M1: liver. Postoperative course was complicated by a wound abscess with drainage and wound resuture after two weeks (02/13). During two months (04:05/13) started chemotherapy and biologic therapy/six applications of Folfiri+Erbitux/. In June 2013 performed CT: restaging found liver metastases progression in S8 (12 cm3 and 10 cm3) S2 (40 cm3) S7 (9,8 cm3) S5(18,8 cm3 and 3,1 cm3). Subsequent volumometry showed-TLV 2978 ml and FLR 698 ml. The ratio: FLR/TLV was 23%. The patient based on these findings was indicated for ALPPS. The first phase of procedure was performed on August 17, 2013. In the postoperative period for the slow growth FLR observed a dorsal branch of the right portal vein so two weeks later was performed embolization of this the branch. A new CT scan showed 807 ml of FLR and FLR/TLV was 27%. The patient was in good clinical condition so he underwent the second phase of ALPPS on August 31, 2013. Postoperatively found a liver failure, hypoalbuminemia 17.9 g/l, higher level of bilirubin max 61.9 umol/l, and ascites. CT scan revealed abscess foci in the right subphrenic space: solved by puncture aspiration under CT guidance. Further course showed a gradual improvement of liver function. Patient discharged on September 25, 2013 (25 days after II. phase of ALLPS). In the next period (11/13) the rise of markers CA 19-9 to 74 U/ml and CEA 5,6 U/ml, therefore indicated chemotherapy with Xeloda, but terminated after the second cycle for patient´s intolerance. Repeated PET: CT (04/14) was without viable tumor tissue. Approximately 13 months after surgery (09/14) again elevation of CA 19:9 to 110 U/ml and performed PET : CT found a recurrence in an anastomosis after sigmoid resection. It was confirmed by colonoscopy too. The patient was indicated subsequently (10/14) to re:resection of the left colon with double:stapling and protective ileostomy and postoperative radiotherapy 56 Gy. The ileostomy closure was performed on May 7, 2015. Now, during May 2015, the patient was fully clinically stabilized without evidence of metastatic disease.

Discussion

According to the current recommended oncological procedure, the only curative solution to malignant liver tumours is surgical resection [5,8,10,13,17,19,31,36,37]. Unfortunately, upon the diagnosis of the tumour, a large percentage of patients already has multiple foci in both liver lobes [5]. ALPPS method is based on the principle of hepatic parenchyma hypertrophy induced by ligation of the portal branch for the lobe to be removed in the future. This lobe is nourished for several days only by arterial blood and, as a compensation, the other lobe which is to remain becomes hypertrophied. The limiting factors of resection include future liver remnant, because the hardest postoperative complication of liver resection is liver failure with a mortality of about 32% [33]. In terms of assessing the amount of unremoved liver tissue, there are two important indicators: FLR/TLV (total liver volume), which determines the share of unremoved tissue to the total volume of healthy liver, and FLR/BW (body weight) to determine the ratio of unremoved tissue to the patient's body weight. FLR/TLV must be higher than 25:30% in healthy liver, or 35:40% in significantly steatotic liver, liver after chemotherapy or with cholestasis above 50 mmol/L. The FLR/BW index must be at least 0.5 in healthy livers or 0.8 in unhealthy ones [5,6,12,14,18,23,38]. Postoperative volumometry should also be performed with densitometry to distinguish postoperative oedema from the right liver tissue hypertrophy. In the case of an oedema, there is a decrease in density, while existing statistics show that liver splitting leads to an increase in the density of parenchyma in the range of 80:120HU [6]. The timetable for two:stage resection is based on the pathophysiology fact that after in situ liver transection with ligation of portal branches for the unhealthy lobe, the daily gain of parenchyma mass is 22% per day versus 3% per day for PVE [6]. The cause of this phenomenon has not yet been examined or explained in detail; discussion focuses on the possible influence of the following factors: (1) portal branch ligation redistributes hepatotrophic substances into a liver remnant : cytokines, growth factor and hormones [33,39-41], (2) the section of the liver is a major traumatic impulse to increase regenerative activity (3) the influence on portal flow in terms of increased flow through liver remnant branch is an important stimulus. In addition, portal neo:collaterals were identified after PVE growing through to deportalised segments. These neo:collaterals appear to be one of the main causes of hypertrophy failure after PVE or isolated PVL [9], (4) unremoved pathological liver tissue always retains certain metabolic activity, which constitutes an important auxiliary factor in the crucial first week after the first stage of resection until FLR hypertrophies to the required size [5,33]. Although the exact pathophysiological mechanism of hypertrophy has not yet been examined in detail, it has been found that previous radiological embolisation of portal branch also does not lead to the “exhaustion” of the hypertrophic potential of the liver [6]. At first glance, the method of embolisation and ligation are the same, with ALPPS having higher morbidity and mortality. According to the data from literature, ALPPS technique morbidity ranges from 9% to 71%, mortality from 0% to 13% [2,6,12,14,36,42]. Such high morbidity is most often caused by complications caused by laparotomy; other frequent causes of postoperative complications reported in the literature include ascites and biliary leak [11,12]. However, when considering the 30% of patients after embolisation who do not reach the second stage of hepatectomy due to tumour progression during the hypertrophy interval and on the other hand feasibility ALPPS rate of nearly 100% we get a slightly different perspective of the high frequency of postoperative complications [6,43]. Overall, the ALPPS method is based on a two:stage liver resection; however, the portal branch ligation has shortened the time required for hypertrophy to a minimum. The splitting of the liver removes the ligation limitation, the limitation probably being the quite strong creation of intrahepatic porto:portal neo:collaterals, which lower portal ligature efficiency compared with embolisation, where the aforementioned induction is not so pronounced [9,21,43]. In the postoperative period, the patients are given antibiotics and, with regard to the protection of the liver parenchyma, no chemotherapeutic treatment is applied during this period. Ascites is corrected with diuretics and albumin, which is usually substituted in the case of a decrease in plasma albumin levels below 30 g/L. In any case, despite the rapid FLR hypertrophy, the method is so far encumbered with a high percentage of complications [42]. The comparison of the results of individual groups of patients allowed the identification of underlying risk factors that demonstrably increase ALPPS morbidity and mortality. This concerns the above-60 age group, non:colorectal tumour metastases, HCC, cholangiocellular carcinoma and biliary reconstruction during ALPPS [9,12,14,17,44].

Conclusion

The ALPPS is a new, developing method and, as such, it is struggling with enthusiasm and confidence on the one hand, and scepticism and rejection on the other. Undoubtedly, the method offers future promise for a significant percentage of patients with liver cancer. However, the method also exhibits high morbidity and mortality, requiring long:term monitoring and comparison of diagnostic procedures, indications, contraindications, operation strategies and, ultimately, primarily monitoring and evaluation of long-term results of “high-volume centres” worldwide.

References

- Skalicky T (2011) History of liver surgery. Hepato: pankreato: biliárníchirurgie, Praha, Maxdorf , ISBN 78: 80: 7345: 269-8.

- de Santibañes E, Clavien PA (2012) Playing Play-Doh to prevent postoperative liver failure: the "ALPPS" approach.Ann Surg 255: 415-417.

- Adam R, Laurent A, Azoulay D, Castaing D, Bismuth H (2000) Two-stage hepatectomy: A planned strategy to treat irresectable liver tumors.Ann Surg 232: 777-785.

- Jaeck D,Oussoultzoglou E, Rosso E, Greget M, Weber JC, et al. (2004) A two stage hepatectomy procedure combined with portal vein embolization to achieve curative resection for initially unresectable multiple and bilobar colorectal liver metastases. Ann. Surg 240: 1037-1051.

- Alvarez FA, Ardiles V, Sanchez Claria R, Pekolj J, de Santibañes E (2013) Associating liver partition and portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy (ALPPS): tips and tricks.J GastrointestSurg 17: 814-821.

- Knoefel WT, Gabor I, Rehders A, Alexander A, Krausch M, et al. (2013) In situ liver transection with portal vein ligation for rapid growth of the future liver remnant in two-stage liver resection.Br J Surg 100: 388-394.

- Abulkhir A, Limongelli P, Healey AJ, Damrah O, Tait P, et al. (2008) Preoperative portal vein embolization for major liver resection: a meta-analysis.Ann Surg 247: 49-57.

- Zhang, Guan:Qi(2012)Associating liver partition and portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy (ALPPS): A new strategy to increase resectability in liver Sumery.International Journal of Surgery 12: 437-441.

- Bertens KA, Hawel J, Lung K, Buac S, Pineda-Solis K, et al. (2015) ALPPS: challenging the concept of unresectability--a systematic review.Int J Surg 13: 280-287.

- Croome KP, Hernandez-Alejandro R, Parker M, Heimbach J, Rosen C, et al. (2015) Is the liver kinetic growth rate in ALPPS unprecedented when compared with PVE and living donor liver transplant? A multicentre analysis.HPB (Oxford) 17: 477-484.

- www.alpps.net

- Schnitzbauer AA, Lang SA, Goessmann H, Nadalin S, Baumgart J, et al. (2012) Right portal vein ligation combined with in situ splitting induces rapid left lateral liver lobe hypertrophy enabling two:staged extended right hepatic resection in small:for:size settings. Ann. Surg255: 405-414.

- Loos M, Friess H (2012) Is there new hope for patients with marginally resectable liver malignancies.World J GastrointestSurg 4: 163-165.

- Li J, Girotti P, Königsrainer I, Ladurner R, Königsrainer A, et al. (2013) ALPPS in right trisectionectomy: a safe procedure to avoid postoperative liver failure?J GastrointestSurg 17: 956-961.

- Andriani OC (2012) Long:term results with associating liver partition and portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy (ALPPS). Ann. Surg256: e5.

- Narita M, Oussoultzoglou E, Ikai I, Bachellier P, Jaeck D (2012) Right portal vein ligation combined with in situ splitting induces rapid left lateral liver lobe hypertrophy enabling 2:staged extended right hepatic resection in small:for:size settings. Ann Surg 256: e7-8

- Schadde E, Ardiles V, Robles-Campos R, Malago M, Machado M, et al. (2014) Early survival and safety of ALPPS: first report of the International ALPPS Registry.Ann Surg 260: 829-836.

- Primrose JN (2010) Surgery for colorectal liver metastases.Br J Cancer 102: 1313-1318.

- Truant S (2015) e:HPBchir Study Group from the Association de ChirurgieHépato:Biliaire et de Transplantation (ACHBT).:Associating liver partition and portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy (ALPPS): Impact of the inter:stages course on morbi:mortality and implications for management. Eur J SurgOncol 4: 674-682.

- Lau L, Christophi C, Muralidharan(2014) Intraoperative functional liver remnantassessment with indocyanine green clearance: another toehold for climbingthe “ALPPS”, Ann. Surg.

- Jaeck D (2003) One or two:stagehepatectomy combined with portal vein emboilization for initially nonresectable colorectal metastase. Am. Surg 185: 221-229.

- Dokmak S, Belghiti J (2012) Which limits to the "ALPPS" approach?Ann Surg 256: e6.

- Sala S, Ardiles V, Ulla M, Alvarez F, Pekolj J, et al. (2012) Our initial experience with ALPPS technique: encouraging results.Updates Surg 64: 167-172.

- Hernandez-Alejandro R, Bertens KA2, Pineda-Solis K2, Croome KP3 (2015) Can we improve the morbidity and mortality associated with the associating liver partition with portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy (ALPPS) procedure in the management of colorectal liver metastases?Surgery 157: 194-201.

- Gauzolino R, Castagnet M, Blanleuil ML, Richer JP (2013) The ALPPS technique for bilateral colorectal metastases: three "variations on a theme".Updates Surg 65: 141-148.

- Gall TM, Sodergren MH, Frampton AE, Fan R, Spalding DR, et al. (2015) Radio-frequency-assisted Liver Partition with Portal vein ligation (RALPP) for liver regeneration.Ann Surg 261: e45-46.

- Robles Campos R, ParrillaParicio P, LópezConesa A, Brusadín R, LópezLópez V, et al. (2013) [A new surgical technique for extended right hepatectomy: tourniquet in the umbilical fissure and right portal vein occlusion (ALTPS). Clinical case].Cir Esp 91: 633-637.

- Machado MA, Makdissi FF, Surjan RC (2012) Totally laparoscopic ALPPS is feasible and may be worthwhile.Ann Surg 256: e13.

- Conrad C, Shivathirthan N, Camerlo A, Strauss C, Gayet B (2012) Laparoscopic portal vein ligation with in situ liver split for failed portal vein embolization.Ann Surg 256: e14-15.

- Cai X, Peng S, Duan L, Wang Y, Yu H, et al. (2014) Completely laparoscopic ALPPS using round-the-liver ligation to replace parenchymal transection for a patient with multiple right liver cancers complicated with liver cirrhosis.J LaparoendoscAdvSurg Tech A 24: 883-886.

- Schadde E, Malagó M, Hernandez-Alejandro R, Li J, Abdalla E, et al. (2015) Monosegment ALPPS hepatectomy: extending resectability by rapid hypertrophy.Surgery 157: 676-689.

- Aloia TA, Vauthey JN (2012) Associating liver partition and portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy (ALPPS): what is gained and what is lost?Ann Surg 256: e9.

- de Santibañes E, Alvarez FA, Ardiles V (2012) How to avoid postoperative liver failure: a novel method.World J Surg 36: 125-128.

- Torres OJ, Fernandes Ede S, Oliveira CV, Lima CX, Waechter FL, et al. (2013) Associating liver partition and portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy (ALPPS): the Brazilian experience.Arq Bras Cir Dig 26: 40-43.

- Jain HA, Bharathy KG, Negi SS (2012) Associating liver partition and portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy: will the morbidity of an additional surgery be outweighed by better patient outcomes in the long-term?Ann Surg 256: e10.

- Torres OJ, Moraes-Junior JM, Lima e Lima NC, Moraes AM (2012) Associating liver partition and portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy (ALPPS): a new approach in liver resections.Arq Bras Cir Dig 25: 290-292.

- Maroulis I, Karavias DD, Karavias D (2011) General principles of hepatectomy in colorectal liver metastases.Tech Coloproctol 15 Suppl 1: S13-16.

- Cavaness KM, Doyle MB, Lin Y, Maynard E, Chapman WC (2013) Using ALPPS to induce rapid liver hypertrophy in a patient with hepatic fibrosis and portal vein thrombosis.J GastrointestSurg 17: 207-212.

- Yokoyama Y, Nagino M, Nimura Y (2007) Mechanisms of hepatic regeneration following portal vein embolization and partial hepatectomy: a review.World J Surg 31: 367-374.

- Mortensen KE, Revhaug A (2011) Liver regeneration in surgical animal modelsdaistorical perspective and clinical implications, Eur. Surg. Res 46: 1e18.

- Schlegel A, Lesurtel M, Melloul E, Limani P, Tschuor C, et al. (2014) ALPPS: from human to mice highlighting accelerated and novel mechanisms of liver regeneration.Ann Surg 260: 839-846.

- TschuorCh, Sergeant G, Schadde E, Slankamenac K, Clavien PA, et al. (2013) Salvage parenchymal liver transection for patients with insufficient volume increase after portal vein occlusion: An extension of the ALPPS approach. Europ. J. SurgOncol 39: 1230-1235.

- Robles R (2012) Comparative study of right portal vein ligation versus embolisation for induction of hypertrophy in two:stegedhepatectomy for multiple bilateral colorectal liver metastases, Eur J SurgOncol 38: 586-593.

- Nadalin S, Capobianco I, Li J, Girotti P, Königsrainer I, et al. (2014) Indications and limits for associating liver partition and portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy (ALPPS). Lessons Learned from 15 cases at a single centre.Z Gastroenterol 52: 35-42.

Relevant Topics

- Constipation

- Digestive Enzymes

- Endoscopy

- Epigastric Pain

- Gall Bladder

- Gastric Cancer

- Gastrointestinal Bleeding

- Gastrointestinal Hormones

- Gastrointestinal Infections

- Gastrointestinal Inflammation

- Gastrointestinal Pathology

- Gastrointestinal Pharmacology

- Gastrointestinal Radiology

- Gastrointestinal Surgery

- Gastrointestinal Tuberculosis

- GIST Sarcoma

- Intestinal Blockage

- Pancreas

- Salivary Glands

- Stomach Bloating

- Stomach Cramps

- Stomach Disorders

- Stomach Ulcer

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 15549

- [From(publication date):

June-2015 - Aug 15, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 10880

- PDF downloads : 4669