Body Mass Index Differences and Parities on Knowledge of Myocardial Infarction among Public and Outpatients in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Cross-Sectional Study in Greater Gaborone, Botswana

Received: 29-Apr-2024 / Manuscript No. JOWT-24-133433 / Editor assigned: 01-May-2024 / PreQC No. JOWT-24-133433 (PQ) / Reviewed: 15-May-2024 / QC No. JOWT-24-133433 / Revised: 22-May-2024 / Manuscript No. JOWT-24-133433 (R) / Published Date: 29-May-2024

Abstract

Objective: In this questionnaire-based study from Botswana, we assessed knowledge of Myocardial Infarction (MI) symptoms and risk factors among the general public and outpatients with MI risk factors based on Body Mass Index (BMI), in addition to assessing associations with sociodemographic and MI risk factors.

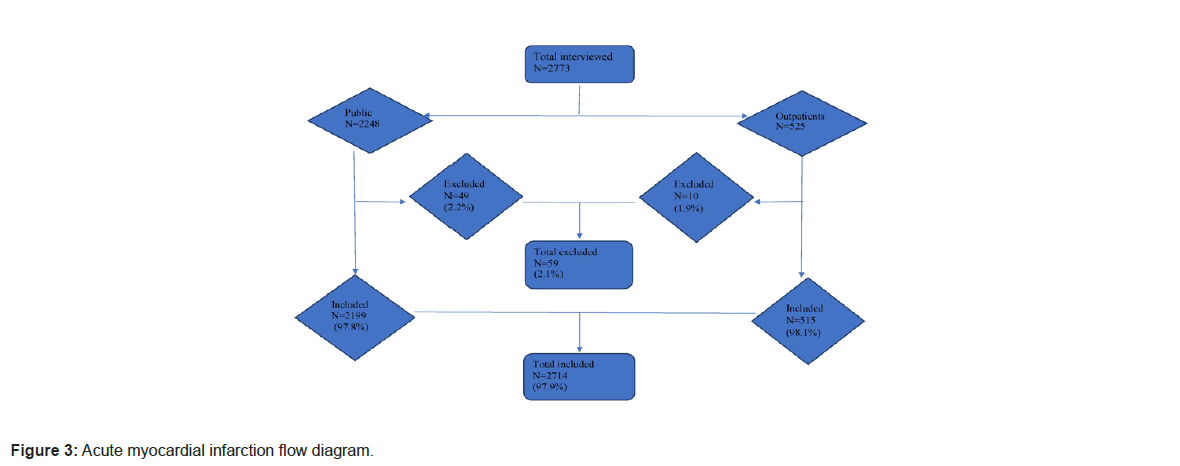

Method: The questionnaires comprised of open-ended questionnaires: 8 MI symptoms and 10 risk factors. They were administered by research assistants to a representative selection of 525 outpatients and 2248 public respondents. BMI was calculated after measuring weight and height in all respondents. Comparison of knowledge scores between the two groups was performed. We investigated whether BMI adjusted sociodemographic and MI risk factors had influence on the scores.

Results: The valid response rates were as follows: 2199 for public respondents (97.8%) and 515 for outpatients (98.1%). Public respondents had mean age (± SD) 35.2 ± 12.3 years while outpatients had 38.5 ± 12.6 years. The public and outpatients consisted of 43.1% and 45.4% males respectively.

In general, outpatients had higher knowledge of MI symptoms than the public among those with normal BMI, mean scores (95% CI) of 3.79 (3.47-4.10) vs. 2.95 (2.70-3.10). Outpatients also had higher knowledge score of MI risk factors than the public among those with normal BMI, 5.52 (5.16-5.89) vs. 3.96 (3.78-4.15), overweight, 5.40 (4.82-5.99) vs. 3.94 (3.70-4.18), and obesity, 4.56 (3.87-5.25) vs. 3.27 (2.99-3.55). For MI symptoms, outpatients had higher awareness than the public for chest pains among those overweight.

Among those with normal BMI and overweight for both outpatients and public, lower knowledge of MI symptoms was associated with not residing/working together. Among those with normal BMI for both outpatients and public, lower knowledge of MI symptoms was associated with primary education, and no family history of stroke/heart diseases. Among those overweight and obese for both outpatients and public, lower knowledge of symptoms was associated with family history of heart diseases, while among obese was also with history of hypertension. There were variations and parities on MI knowledge among respondents with various BMIs.

Conclusion: Results call for urgent educational campaigns based on BMI for MI awareness and knowledge.

Keywords: Myocardial infarction; Body mass index; Knowledge; Awareness; Symptoms; Public; Risk factors; Outpatients

Introduction

Ischemic Heart Disease (IHD) is increasing and remains the leading cause of all health loss worldwide including each and every region of the world with 110.6 and 197 million prevalent cases, and about 8.9 and 9.14 million deaths in 2015 and 2019 respectively [1,2]. This has led to the increment of total number of Disability-Adjusted Life-Years (DALYs) since 1990, reaching 182 million DALYs, [1]. IHD is the principal cause of death in developed countries and is one of the leading causes of disease burden in developing countries [3]. In Botswana, IHD was the second leading cause of mortality after HIV/ AIDS from 2005-2016, with an increment of 9.2% according to the Global Burden of Diseases 2016 (GBD 2016) study [4-8]. Early contact with a hospital when developing acute MI symptoms factors lead to better optimal acute treatment of acute MI (thrombolytic therapy and/or Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI)) while management of MI risk factors to better prevention strategies [9,10]. This depends on patients, their families, and general populations knowledge of acute MI. Globally, some community-based studies have been carried out to investigate public awareness of acute MI risk factors, warning signs, and perceived intentions to take when acute MI is suspected [11-22], but only a few have been carried out in Sub-Saharan Africa, including one in Botswana [23].

Worldwide, about 2.5 billion adults (i.e., 43% of men and 44% of women) were overweight, of which 890 million adults were obese in 2022 [24,25]. The worldwide prevalence of obesity more than doubled between 1990 and 2022 [25]. Obesity is associated with risk for AMI [26-28], and a higher prevalence of co-morbidities of MI risk factors like diabetes, insulin resistance, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension [29,30]. In addition, underweight patients have been shown to have a higher risk of cardiovascular events (cerebrovascular accidents and AMI) [31,32].

There is a meagre of open-ended studies that have been carried out globally to assess awareness of MI symptoms [10,21,22,33-35] in comparison to closed-ended studies [33,36-48]. We found only one previous open-ended MI risk factors study [23]. They have been shown higher knowledge/awareness of MI among closed-ended studies compared to open-ended ones. This is because closed-ended questions overestimate the real level of awareness and knowledge, as demonstrated in some previous studies [33,49]. According to our knowledge, there are also no Body Mass Index (BMI) based studies on MI knowledge/ awareness worldwide, including Sub-Saharan Africa.

Objectives

1) To investigate knowledge of myocardial infarction symptoms and risk factors among the public and outpatients based on body mass index in Botswana, 2) To determine if respondents’ BMI adjusted sociodemographic and myocardial infarction risk factors are associated with MI knowledge.

Materials and Methods

Study design

We performed a cross-sectional study, and participants were recruited from greater Gaborone, Botswana, as demonstrated in the previous study [23]. We sampled two (2) groups of participants: The general public and outpatients. For more information, see below methods from the previous study [23].

Study methods

Study design and setting: There were two (2) types of respondents: General public with or without MI risk factors that were recruited from their homes or workplaces in both rural and urban areas. The second type were outpatients who are patients with at least one MI risk factor, recruited from both primary and secondary healthcare facilities while waiting in a queue for or after consultation. Recruiting of respondents from the public and outpatients from healthcare facilities were done concurrently so as to avoid the bias of respondents being interviewed twice. This was clarified by asking the respondents if they have recently participated in a stroke study this year. If the answer was yes, they would not be recruited.

Trained research assistants interviewed respondents verbatim. Each interviewer conducted a standardized, structured, one-to-one interview, according to a multi-sectioned questionnaire designed to guide the interview and avoid bias. The interviewer intervened only if asked to clarify any question, without giving correct answers. Respondents were verbally informed about the study and written consent solicited prior to participation.

Sampling of study places and population: All names of the four(4) districts in Greater Gaborone except Gaborone City and Lobatse town were put in a box, and two (2) names were blindly selected from the box as study places in addition to Gaborone city and Lobatse town. This applied also to healthcare facilities and communities in the selected districts.

For Gaborone city, all areas were categorized into three socio- economic groups i.e., low, middle and high income. Names of more than three (3) areas with similar socio-economic category were put in a box and three (3) names were blindly selected to represent that specific category. If they were only two areas in the same category, they were both included. This included Phakalane and Extension (high income), Blocks and Broadhurst (middle income), Old Naledi, Bontleng, and Tsolamosese (low income).

Respondents from the general public were recruited from their homes or workplaces in both rural and urban areas. Rural areas included Molepolole in the Kweneng, Mathubudukwane and Mochudi in Kgatleng, while urban areas included the capital city, Gaborone. For the general public in each selected area, we selected households or companies with odd numbers. No more than two respondents from the same family/compound/company were interviewed.

For outpatients, they were interviewed while waiting in a queue for or after consultation, and only odd numbers were interviewed. Outpatients were recruited from both primary and secondary healthcare facilities. They were screened by a healthcare facility nurse/ doctor for eligibility before informed consent was given. Primary healthcare refers to first line of healthcare, included medical health clinics for outpatients where there are nurses and/or medical doctors which can refer patients to district hospitals. Public health clinics in all districts are run by District Health Management Team (DHMT). Primary healthcare included two out of six DHMTs in greater Gaborone (Nkoyaphiri clinic and Phuthadikobo clinic in Kweneng, and Phaphane clinic and Mathubudukwane clinic in Kgatleng). Secondary healthcare refers to where primary healthcare refers to, consists of hospital healthcare staff (general doctors and some specialists (internal medicine, general surgery), nurses, laboratory technicians, etc.), and is capable of admitting patients. Secondary healthcare included district hospitals (Scottish Livingstone hospital in Kweneng, and Deborah Retief Memorial Hospital in Kgatleng), and the only tertiary referral psychiatric hospital in the country (Sbrana Psychiatric Referral hospital in Lobatse).

Sample size: We have calculated sample size based on the finite formula below, using 5% as margin of error, 95% confidence interval, 50% population proportion, and population size of 2 million for Botswana regarding the general public, while for outpatients we used based on 1/4 of the general population.

Unlimited population:

Finite population:

Where z is the z score, ε is the margin of error, N is the population size, and p̂ is the population proportion.

For the public, it gave us 385 as the sample size. Since we had 15 characteristics or subgroups classified into 3 categories (sociodemographic, self-reported stroke risk factors, and calculated stroke risk factors). Dividing 15 by 3 gave us 5. Therefore, we multiplied sample size 385 by 5 which gave 1925 as the sample size. For outpatient population size, we calculated 1/4 of the general population sample size which gave 481.

Pilot study: This was performed on the 10th-13th April 2018 in Southeast District, Otse village, where 36 respondents comprising general public and outpatients were interviewed.

Inclusion criteria

Among the general public, residents or workers in study region with/out MI risk factors were recruited. Outpatients with at least one MI risk factor visiting healthcare facilities in Greater Gaborone during study period, but were not admitted. No more than two (2) respondents from same family, compound or company were included. Participants who could consent, understood English or local language, Setswana, and >18 years old were recruited. Only participants from the randomly selected study places were included.

Exclusion criteria

Those with reduced/loss of cognitive/speech functions or from pilot place.

Data collection instrument

The study instruments were adapted from some study surveys [11,22,33,35,36,51] and were modified to resonate with guidelines for Centres for Diseases Control and Prevention (CDC), World Health Organization (WHO), and European Society of Cardiology [52-54]. The questionnaire was pilot-tested with a sample of 36 participants and some modifications were made based on the results. The questionnaire instruments were anonymous, electronic-based using tablets (Samsung Galaxy Tab 3 Lite, 7.0 Android, South Korea), standardized, written, and administered in English or local language (Setswana). They were open-ended in nature, and categorized into 4 sections, as shown in one previous study [23]. Section 1 covered sociodemographic factors, section 2-awareness of MI symptoms, section 3-awareness of MI risk factors, while section 4-self-reported and calculated MI risk factors (BMI). They were analyzed as in the previous study [23].

BMI was calculated, and classified as defined by the WHO and National Institutes of Health (NIH) i.e., underweight as BMI2, normal BMI 18.5-2, overweight 25-2, and obesity as ≥ 30 kg/m2 [55-56]. These calculated BMIs were used to stratify awareness and were also adjusted for knowledge of MI symptoms and risk factors.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as means ± Standard Deviation (SD) or 95% Confidence Interval (CI) while categorical/ ordinal variables as frequency (n) and proportion (%) of the overall sample. MI symptoms and risk factors awareness were stratified by BMI. Chi-squared was used to compare awareness rates of outpatients and the public.

We utilized two-way ANOVA to assess BMI-adjusted sociodemographic and MI risk factors’ association with MI knowledge scores if the data was normally distributed. If not normally distributed, non-parametric analysis would be used. Bonferroni analysis was preferred to correct for multiple comparisons. Statistical tests were two-tailed and reported statistically significant at p

Results

In the period from June to October 2019, 2773 respondents were interviewed. Fifty-nine (59) participants were excluded because of missing substantial information necessary for the study. The valid response was 97.9% (2714 respondents), comprising 97.8% of the public (2199) and 98.1% of outpatients (515). Public respondents had a mean age of 35.2 ± 12.3 years, and age range 18-82 years while outpatients had 38.5 ± 12.6 years, and age range 18-78 years. Public and outpatients comprised 43.1% and 45.4% males respectively. Among the public, 47% (1033) were overweight of which 18.4% were obese while among outpatients, 39.8% (205) were overweight of which 17.7% were obese. For more information, refer to Table 1.

|

|

Total n=2715 | Public n=2199 | Outpatients n=515 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Sociodemographic factors | ||||

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 1532 (56.4) | 1251 (56.9) | 281 (54.6) | 0.338 |

| Male | 1182 (43.6) | 948 (43.1) | 234 (45.4) | - |

| Age category (years) | ||||

| 18-34 | 1447 (53.3) | 1238 (56.3) | 209 (40.6) | <0.001 |

| 35-49 | 894 (32.9) | 683 (31.1) | 211 (41.0) | - |

| >50 | 373 (13.7) | 278 (12.6) | 95 (18.4) | - |

| Education level | ||||

| Primary, or unknown | 307 (11.3) | 255 (11.6) | 52 (10.1) | 0.486 |

| Secondary | 1311 (48.3) | 1052 (47.8) | 259 (50.3) | - |

| Tertiary | 1096 (40.4) | 892 (40.6) | 204 (39.6) | - |

| Medical insurance | ||||

| Yes | 373 (13.7) | 274 (12.5) | 99 (19.2) | <0.001 |

| No, unknown | 2341 (86.3) | 1925 (87.5) | 416 (80.8) | - |

| Residing/working together | ||||

| Yes | 857 (31.6) | 673 (30.6) | 184 (35.7) | 0.024 |

| No | 1857 (68.4) | 1526 (69.4) | 331 (64.3) | - |

| Self-reported risk factors | ||||

| History of hypertension | ||||

| Yes | 258 (9.5) | 161 (7.3) | 97 (18.8) | <0.001 |

| No, unknown | 2456 (90.5) | 2038 (92.7) | 418 (81.2) | - |

| History of CVDS | ||||

| Yes | 131 (4.8) | 70 (3.2) | 61 (11.8) | <0.001 |

| No | 2583 (95.2) | 2129 (96.8) | 454 (88.2) | - |

| Family history of stroke/heart diseases | ||||

| None | 760 (28.0) | 711 (32.3) | 49 (9.5) | <0.001 |

| Both heart diseases and stroke | 739 (27.2) | 566 (25.7) | 173 (33.6) | - |

| Heart diseases | 851 (31.4) | 649 (29.5) | 202 (39.2) | - |

| Stroke | 364 (13.4) | 273 (12.4) | 91 (17.7) | - |

| BMI | ||||

| Underweight | 95 (3.5) | 78 (3.5) | 17 (3.3) | 0.006 |

| Normal, unknown | 2048 (75.5) | 1651 (75.1) | 397 (77.1) | - |

| Overweight | 539 (19.9) | 451 (20.5) | 88 (17.1) | - |

| Obesity | 32 (1.2) | 19 (0.9) | 13 (2.5) | - |

| Healthy dietary status | ||||

| No, unknown | 1039 (38.3) | 909 (41.3) | 130 (25.2) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 1675 (61.7) | 1290 (58.7) | 385 (74.8) | - |

| Alcohol consumption | ||||

| No, unknown | 1907 (70.3) | 1559 (70.9) | 348 (67.6) | 0.003 |

| Current | 730 (26.9) | 589 (26.8) | 141 (27.4) | - |

| Former | 77 (2.8) | 51 (2.3) | 26 (5.0) | - |

| Smoking status | ||||

| No, unknown | 2297 (84.6) | 1888 (85.9) | 409 (79.4) | <0.001 |

| Current | 355 (13.1) | 271 (12.3) | 84 (16.3) | - |

| Former | 62 (2.3) | 40 (1.8) | 22 (4.3) | - |

| Intensity of physical activity | ||||

| None, unknown | 1860 (68.5) | 1534 (69.8) | 326 (63.3) | 0.004 |

| Light | 225 (8.3) | 174 (7.9) | 51 (9.9) | - |

| Moderate | 507 (18.7) | 387 (17.6) | 120 (23.3) | - |

| High | 122 (4.5) | 104 (4.7) | 18 (3.5) | - |

| History of HIV/AIDS | ||||

| Yes | 491 (18.1) | 277 (12.6) | 214 (41.6) | <0.001 |

| No, unknown | 2223 (81.9) | 1922 (87.4) | 301 (58.4) | - |

| History of psychiatric diseases | ||||

| Yes | 90 (3.3) | 0 (0) | 90 (17.5) | <0.001 |

| No | 2624 (96.7) | 2199 (100.0) | 425 (82.5) | - |

| Calculated risk factors | ||||

| BMI | ||||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 99 (3.6) | 87 (4.0) | 12 (2.3) | 0.001 |

| Normal (18.5<25), unknown | 1377 (50.7) | 1079 (49.1) | 298 (57.9) | - |

| Overweight (25<30) | 742 (27.3) | 628 (28.6) | 114 (22.1) | - |

| Obesity (>30) | 496 (18.3) | 405 (18.4) | 91 (17.7) | - |

Note: NA: Not Applicable; CVDS: Cardiovascular Risk factors (diabetes, dyslipidemia, stroke, or heart diseases); Psychiatric diseases: depression or anxiety; BMI: Body Mass Index.

Table 1: Sociodemographic and myocardial infarction risk factors among respondents.

Awareness of MI symptoms stratified by BMI

Among those with normal BMI, outpatient had higher awareness than the public for central chest pains, arm pain/numbness and neck/ jaw pain radiating from chest as acute MI symptoms while among those overweight, outpatients had higher awareness than the public for central chest pain as an acute MI symptom (p<0.05) (Table 2). Among those underweight and obese, there were no awareness differences between outpatients and the public. For all BMI subgroups among both outpatients and the public, highest spontaneously recalled acute MI symptoms were central chest pains, shortness of breath and fainting/ dizziness while lowest recalled was nausea.

| Normal BMI | Public aware (%) n=1079 | Outpatients aware (%) n=298 | p* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shortness of breath | 722 (66.9) | 198 (66.4) | 0.95 |

| Central chest pain | 478 (44.3) | 228 (76.5) | <0.001 |

| Fainting/ dizziness | 600 (55.6) | 192 (64.4) | 0.218 |

| Arm pain/ numbness | 288 (26.7) | 120 (40.3) | 0.011 |

| Feeling sick or looking pallor on the skin | 354 (32.8) | 119 (39.9) | 0.202 |

| Sweating and clammy skin | 316 (29.3) | 100 (33.6) | 0.409 |

| Neck/ jaw pain radiating from chest | 298 (27.6) | 119 (39.9) | 0.021 |

| Nausea | 122 (11.3) | 52 (17.4) | 0.08 |

| Underweight | n=87 | n=12 | |

| Shortness of breath | 51 (58.6) | 8 (66.7) | 0.826 |

| Central chest pain | 39 (44.8) | 8 (66.7) | 0.501 |

| Fainting/ dizziness | 45 (51.7) | 8 (66.7) | 0.65 |

| Arm pain/ numbness | 17 (19.5) | 5 (41.7) | 0.361 |

| Feeling sick or looking pallor on the skin | 23 (26.4) | 6 (50.0) | 0.375 |

| Sweating and clammy skin | 27 (31.0) | 5 (41.7) | 0.691 |

| Neck/ jaw pain radiating from chest | 23 (26.4) | 6 (50.0) | 0.375 |

| Nausea | 12 (13.8) | 3 (25.0) | 0.55 |

| Overweight | n=628 | n=114 | |

| Shortness of breath | 435 (69.3) | 72 (63.2) | 0.602 |

| Central chest pain | 262 (41.7) | 71 (62.3) | 0.047 |

| Fainting/ dizziness | 353 (56.2) | 71 (62.3) | 0.581 |

| Arm pain/ numbness | 158 (25.2) | 43 (37.7) | 0.119 |

| Feeling sick or looking pallor on the skin | 178 (28.3) | 37 (32.5) | 0.601 |

| Sweating and clammy skin | 191 (30.4) | 42 (36.8) | 0.441 |

| Neck/ jaw pain radiating from chest | 164 (26.1) | 36 (31.6) | 0.477 |

| Nausea | 64 (10.2) | 13 (11.4) | 0.792 |

| Obesity | n=405 | n=91 | |

| Shortness of breath | 231 (57.0) | 42 (46.2) | 0.355 |

| Central chest pain | 142 (35.1) | 42 (46.2) | 0.291 |

| Fainting/ dizziness | 193 (47.7) | 39 (42.9) | 0.661 |

| Arm pain/ numbness | 92 (22.7) | 29 (31.9) | 0.284 |

| Feeling sick or looking pallor on the skin | 85 (21.0) | 22 (24.2) | 0.678 |

| Sweating and clammy skin | 93 (23.0) | 24 (26.4) | 0.68 |

| Neck/ jaw pain radiating from chest | 84 (20.7) | 26 (28.6) | 0.337 |

| Nausea | 26 (6.4) | 9 (9.9) | 0.453 |

Note: P*: Calculated using chi-squared; BMI: Body Mass Index.

Table 2: Awareness of acute myocardial infarction symptoms between public and outpatients stratified by BMI.

Awareness of MI risk factors stratified by BMI

Among those with normal BMI, overweight and obesity, outpatients had higher awareness than the public for smoking (p<0.05) (Table 3). Among those with normal BMI and overweight, outpatients had higher awareness than the public for diabetes as a risk factor while among those with normal BMI, outpatients had higher awareness than the public for hypertension, dyslipidemia, heavy alcohol intake, previous stroke, and family history of stroke/heart diseases. For all BMI subgroups among both outpatients and public, highest spontaneously recalled MI risk factors were hypertension and obesity, except among underweight where outpatients recalled dyslipidemia instead of obesity. For all BMI subgroups among both outpatients and public, family history of stroke/ heart diseases was the least spontaneously recalled risk factor.

| Public aware (%) | Outpatients aware (%) | p* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal BMI | n=1079 | n=298 | |

| Hypertension | 652 (60.4) | 240 (80.5) | 0.009 |

| Dyslipidemia | 262 (24.3) | 132 (44.3) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 412 (38.2) | 181 (60.7) | <0.001 |

| Sedentary lifestyle | 429 (39.8) | 131 (44.0) | 0.483 |

| Heavy alcohol intake | 414 (38.4) | 162 (54.4) | 0.011 |

| Previous stroke | 296 (27.4) | 119 (39.9) | 0.02 |

| Heart diseases | 442 (41.0) | 151 (50.7) | 0.12 |

| Family history of stroke/ heart diseases | 171 (15.8) | 83 (27.9) | 0.005 |

| Obesity | 721 (66.8) | 240 (80.5) | 0.084 |

| Smoking | 479 (44.4) | 207 (69.5) | <0.001 |

| Underweight | n=87 | n=12 | |

| Hypertension | 46 (52.9) | 10 (83.3) | 0.397 |

| Dyslipidemia | 18 (20.7) | 8 (66.7) | 0.105 |

| Diabetes | 26 (29.9) | 5 (41.7) | 0.662 |

| Sedentary lifestyle | 37 (42.5) | 5 (41.7) | 0.973 |

| Heavy alcohol intake | 31 (35.6) | 7 (58.3) | 0.444 |

| Previous stroke | 28 (32.2) | 7 (58.3) | 0.361 |

| Heart diseases | 41 (47.1) | 6 (50.0) | 0.925 |

| Family history of stroke/ heart diseases | 14 (16.1) | 4 (33.3) | 0.427 |

| Obesity | 56 (64.4) | 7 (58.3) | 0.867 |

| Smoking | 32 (36.8) | 7 (58.3) | 0.466 |

| Overweight | n=628 | n=114 | |

| Hypertension | 375 (59.7) | 92 (80.7) | 0.081 |

| Dyslipidemia | 158 (25.2) | 40 (35.1) | 0.207 |

| Diabetes | 229 (36.5) | 67 (58.8) | 0.024 |

| Sedentary lifestyle | 258 (41.1) | 56 (49.1) | 0.403 |

| Heavy alcohol intake | 224 (35.7) | 61 (53.5) | 0.063 |

| Previous stroke | 162 (25.8) | 43 (37.7) | 0.141 |

| Heart diseases | 257 (40.9) | 56 (49.1) | 0.396 |

| Family history of stroke/ heart diseases | 90 (14.3) | 29 (25.4) | 0.082 |

| Obesity | 442 (70.4) | 92 (80.7) | 0.407 |

| Smoking | 278 (44.3) | 80 (70.2) | 0.017 |

| Obesity | n=405 | n=91 | |

| Hypertension | 218 (53.8) | 69 (75.8) | 0.096 |

| Dyslipidemia | 82 (20.2) | 29 (31.9) | 0.165 |

| Diabetes | 112 (27.7) | 38 (41.8) | 0.142 |

| Sedentary lifestyle | 160 (39.5) | 51 (56.0) | 0.143 |

| Heavy alcohol intake | 112 (27.7) | 34 (37.4) | 0.229 |

| Previous stroke | 65 (16.0) | 24 (26.4) | 0.168 |

| Heart diseases | 139 (34.3) | 30 (33.0) | 0.888 |

| Family history of stroke/ heart diseases | 46 (11.4) | 21 (23.1) | 0.082 |

| Obesity | 252 (62.2) | 61 (67.0) | 0.713 |

| Smoking | 138 (34.1) | 58 (63.7) | 0.009 |

Note: p*: Calculated using chi-squared; BMI: Body Mass Index.

Table 3: Awareness of myocardial infarction risk factors between public and outpatients stratified by BMI.

BMI based knowledge scores of MI symptoms and risk factors

There were disparities for MI symptoms, with more outpatients than the public spontaneously recalling all 8 symptoms among those with normal BMI (15.4% vs. 8.5%), underweight (25% vs. 5.7%), overweight (8.8% vs. 6.5%), and obesity (9.9% vs. 4.2%) (Figures 1 and 2). Still more outpatients than the public spontaneously recalled at least one symptom among those with normal BMI (86.6% vs. 78.0%), and underweight (75.0% vs. 71.3%) while higher number of the public did than outpatients among those overweight (82.6% vs. 74.6%), and obese (72.6% vs. 64.8%). Outpatients had significantly higher mean knowledge score (95% CI) than the public among those with normal BMI, 3.79 (3.47-4.10) vs. 2.95 (2.70-3.10). Other mean knowledge scores of outpatients vs. public were as follow: Among those with underweight, 4.08 (1.96-6.21) vs. 2.72 (2.17-3.28), overweight 3.38 (2.85-3.90) vs. 2.87 (2.68-3.06), and obesity 2.56 (1.97-3.15) vs. 2.34 (2.11-2.56).

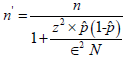

There were variations for MI risk factors knowledge. For those who recalled all 10 risk factors, outpatients were more aware than the public among those with normal BMI (16.8% vs. 7.9%), underweight (25.0% vs. 6.9%), overweight (14.9% vs. 6.1%), and obesity (15.4% vs. 4.2%) (Figures 3 and 4). Still more outpatients than the public spontaneously recalled at least one risk factor among those with normal BMI (95.0% vs. 86.4%), underweight (91.7% vs. 79.3%), overweight (91.2% vs. 89.0%), and obesity (86.8% vs. 82.2%). Regarding MI risk factors, outpatients had significantly higher mean scores (95% CI) than the public among those with normal BMI, 5.52 (5.16-5.89) vs. 3.96 (3.78- 4.15), overweight, 5.40 (4.82-5.99) vs. 3.94 (3.70-4.18), and obesity, 4.56 (3.87-5.25) vs. 3.27 (2.99-3.55). Among those underweight, outpatients score was 5.50 (3.04-7.96) vs. public 3.78 (3.06-4.50) (Figure 5).

Body Mass Index (BMI) association with MI knowledge scores

For both outpatients and public, lower knowledge of MI symptoms was associated with not residing/working together among those with normal BMI and overweight; with primary education, and no family history of stroke/heart diseases among those with normal BMI; with family history of heart diseases among those overweight and obese, while with history of hypertension among those obese (Supplementary Table 1).

For the public among those underweight, lower knowledge of symptoms was associated with male gender, no medical insurance, not residing/working together, and no family history of stroke/ heart diseases, while for outpatients’ counterparts, it was secondary education, low intensity physical activity and no history of HIV/AIDS. For the public among those with normal BMI, it was associated with age 35-49 years, >50 years, history of hypertension, no physical activity, low intensity physical activity, current smokers, non-smokers, and current drinkers while for their outpatient’s counterparts, it was age 18-34 years, secondary education, no medical insurance, not married, moderate intensity physical activity, no history of HIV/AIDS, history of psychiatric diseases, and family history of heart diseases.

For the public among those overweight, lower knowledge was associated with no healthy diet, and no family history of stroke/heart diseases while for outpatients, it was history of hypertension, history of CVDS, no history of HIV/AIDS, and history of psychiatric diseases. For the public among those obese, it was associated with primary education, not residing/working together, and no family history of stroke/heart diseases while for outpatients with history of CVDS, non- smokers, non-drinkers, and no history of HIV/AIDS.

For both outpatients and the public among those with normal BMI, overweight and obesity, lower knowledge of MI risk factors was associated with no family history of stroke/heart diseases with primary education, and no history of HIV/AIDS among those with normal BMI, while with no history of HIV/AIDS among those overweight (Supplementary Table 1).

For the public among those underweight, lower knowledge of MI risk factors was associated with age >50 years, male gender, no medical insurance, not residing/working together, no family history of stroke/ heart diseases while for outpatients, it was no history of HIV/AIDS. For the public among those with normal BMI, it was age >50 years, not residing/working together, no physical activity, current smokers, and current drinkers while for outpatients, it was age 18-34 years, secondary education, no medical insurance, not married, moderate intensity physical activity, history of psychiatric diseases, and family history of heart diseases.

For the public among those overweight, lower knowledge of risk factors was associated with primary education, not residing/working together, and no healthy diet while for outpatients, it was history of hypertension, history of CVDS, history of psychiatric diseases, and family history of heart diseases. For the public among those obese, it was with primary education, secondary education, and no physical activity while for outpatients, it was history of hypertension, history of CVDS, non-smokers, non-drinkers, no history of HIV/AIDS, history of psychiatric diseases, and family history of heart diseases.

Discussion

Our study showed that for the general public, 47% were overweight of which 18.4% were obese. This is in line with other global reporting for overweight while for obesity, ours was underrepresented [24-25]. For MI symptoms, outpatients had higher awareness than the public for central chest pain among those with normal BMI and overweight,while, higher awareness for arm pain/numbness and neck/jaw pain radiating from chest among those with normal BMI and higher awareness for central chest pain among those overweight. Concerning MI risk factors, outpatients had higher awareness than the public for smoking among those with normal BMI, overweight and obesity, while higher awareness for diabetes among those with normal BMI and overweight. Outpatients still had higher awareness than the public for hypertension, dyslipidemia, heavy alcohol intake, previous stroke, and family history of stroke/heart diseases among those with normal BMI. This could be due to frequent visits to healthcare clinics by outpatients, and having more knowledge interest in their comorbidities. There were disparities and parities regarding MI knowledge among respondents with different BMIs. For both outpatients and the public among those with normal BMI and overweight, lower knowledge of MI symptoms was associated with not residing/working together while, it was family history of heart diseases among those with overweight and obesity. For those obese, they had also in addition history of hypertension while for those with normal BMI, had in addition primary education, and no family history of stroke/heart diseases. Residing/working together seems to be crucial in having better knowledge may be due to that people discuss important healthy issues with their colleagues at work and home. Those with hypertension among obese, family history of stroke/heart diseases among overweight and obese, and primary education among normal BMI are unaware of these as risk factors because they already have other risk factors like obesity/overweight to contemplate with and due to low education level. Regarding MI risk factors, for both public and outpatients among those with normal BMI, overweight and obesity, lower knowledge was associated with no family history of stroke/heart diseases while among those with normal BMI, it was associated with primary education, and no history of HIV/AIDS, and among overweight with no history of HIV/AIDS. It is a concern that high-risk participants were associated with lower knowledge. Therefore, these subgroups need to be targeted if we are to reduce MI burden (disability and mortality) in Sub-Saharan Africa. Our study demonstrated that having normal BMI with lower MI knowledge was not associated with fewer number of MI risk factors.

In this study, for all BMI subgroups among outpatients, the most frequently recalled MI symptoms were central chest pain (46.2%- 76.5%), shortness of breath (46.2%-66.7%), and fainting/dizziness (42.9%-66.7%) while lowest recalled was nausea (9.9%-25.0%). It is consistent with some studies [23,34,35] that had central chest pain (67.8-92%) and shortness of breath (39-62.1%) as the most frequently recalled symptoms even though they were not BMI stratified. It is in line also with other studies [19,23] that demonstrated shortness of breath as the most frequently recalled symptom among those aged 65-years and >50-years respectively even though ours was not age stratified.

Among the public for all BMI subgroups, the most frequently recalled MI symptoms were central chest pain (35.1%-44.8%), shortness of breath (57.0%-69.3%) and fainting/dizziness (47.7%-56.2%) while lowest recalled was nausea (6.4%-13.8%). This resonates with some studies that showed shortness of breath, and central chest pain, as the most frequently recalled symptoms even though they were not BMI stratified. It is also consistent with one that demonstrated arm pain/numbness at the one of the least recalled [10,21-23,57]. Our study contradicts other studies that found arm pain/numbness [10,21] as most frequently recalled, while fainting/dizziness was one of the lowest [37]. The differences in these studies could be attributed to no BMI-stratification and differences in the study populations.

Regarding MI symptoms, outpatients demonstrated higher mean knowledge score (95% CI) than the public among those with normal BMI 3.79 (3.47-4.10) vs. 2.95 (2.70-3.10), and more outpatients than the public spontaneously recalled all 8 symptoms among those with normal BMI (15.4% vs. 8.5%), underweight (25% vs. 5.7%), overweight (8.8% vs. 6.5%), and obesity (9.9% vs. 4.2%) Regarding MI risk factors, outpatients had higher mean scores (95% CI) than the public among those with normal BMI, 5.52 (5.16-5.89) vs. 3.96 (3.78-4.15), overweight, 5.40 (4.82-5.99) vs. 3.94 (3.70-4.18), and obesity, 4.56 (3.87- 5.25) vs. 3.27 (2.99-3.55). In addition, more outpatients than the public recalled all-10 risk factors among those with normal BMI (16.8% vs. 7.9%), underweight (25.0% vs. 6.9%), overweight (14.9% vs. 6.1%), and obesity (15.4% vs. 4.2%). This could be attributed to outpatients’ experience, eagerness to learn about diseases, and education from healthcare professionals about MI knowledge.

For normal BMI among public, lower knowledge of MI symptoms was associated with age >35 years, while among outpatients, it was age 18-34 years. It contrasts with other public studies that did not show any association with age [21,22]. This partly resonates with another public study that showed an association with middle-aged persons [10]. It also partly resonates with another study that demonstrated an association of higher knowledge of MI symptoms with age 18-49 years among the public [23]. For those underweight among public, lower knowledge of symptoms was associated with male gender. This contradicts public and outpatients’ studies that did not show any association with gender [21,23]. In our study, for normal BMI among both outpatients and public, lower knowledge of MI symptoms was associated with primary education. In addition, for those obese among public, it was also associated with primary education. This is in line with one study that showed lower knowledge of MI symptoms was associated with low education level among both public and outpatients, and also among those with one lifestyle behaviour [23]. In addition, in our study, for normal BMI and underweight among outpatients, lower knowledge of MI symptoms was associated with secondary education. Our findings contradict one study from Tanzania that found no such association [22].

For those overweight and obese among outpatients, lower knowledge of MI symptoms was associated with a history of CVDS. This is in line with one study that demonstrated association of lower knowledge of MI symptoms with a history of CVDS among outpatients in general and those outpatients with non-healthy lifestyle behaviour [23]. It contrasts some studies that demonstrated higher knowledge among respondents with previous CVDS (heart attack) [10,21,34]. For normal BMI among both outpatients and public, those underweight, overweight and obese among public, lower knowledge of MI symptoms was associated with no family history of stroke/heart diseases. This resonates with one study, that showed lower knowledge of MI symptoms was associated with no family history of stroke/heart diseases among the public with none or one healthy lifestyle behaviour [23]. For those overweight and obese among both outpatients and public, and those with normal BMI among outpatients, lower knowledge of symptoms was associated with family history of heart diseases. This contrasts with one study that demonstrated higher knowledge with respondents who had relatives with heart attack [21]. For those obese among both outpatients and public, overweight among outpatients, and normal BMI among public, lower knowledge of symptoms was associated with history of hypertension. This resonates with one study that demonstrated lower knowledge was associated with history of hypertension for both outpatients and the public with 0-1 healthy lifestyle behaviours, in addition to outpatients with also >2 healthy lifestyle behaviours [23]. For those underweight, normal BMI, overweight and obese among outpatients, it was no history of HIV/ AIDS. This is in line with same study that demonstrated lower knowledge of MI symptoms was associated with no history of HIV/AIDS among outpatients [23]. For those underweight among outpatients, lower knowledge was associated with low intensity physical activity, while for those with normal BMI among public, it was associated with no physical activity, and low intensity physical activity. For normal BMI among public, it was associated with current smokers, and current drinkers. For those overweight among public, lower knowledge was associated with no healthy diet while among outpatients, it was history of psychiatric diseases. This shows that those at high risk with poor lifestyle behaviours have lower knowledge just as demonstrated in one previous study [23]. Therefore, they need to be targeted as well for education campaigns. Most of the variations with previous studies could be attributed to differences in the study population, how age was defined and if they were adjusted for BMI, year of research study and place.

There was only one previous open-ended study on MI risk factors found for comparison with our study. For those underweight among public, lower knowledge of MI risk factors was associated with male gender. Several studies have also demonstrated gender differences in the pathophysiology of atherosclerosis, cardiovascular risk factors, diagnosis of coronary artery diseases and valvular heart disease, and management and outcomes after acute coronary syndromes and valvular repair [58]. This contrasts with one study that did not show any gender associations [23]. For those underweight and with normal BMI among public, lower knowledge of MI risk factors was associated with age >50 years. This is in line with one study that demonstrated that among public with non-healthy lifestyle behaviours, lower knowledge was associated with age ≥ 50 years [23]. But contradicts same study that also showed that among public with non-healthy lifestyle behaviours, lower knowledge of MI risk factors was associated with age 35-49 years while among public with >2 healthy lifestyle behaviours, it was associated with age 18-34 years [23]. For those with normal BMI among outpatients, it was age 18-34 years. This contrasts same study that showed that among outpatients with non-healthy lifestyle behaviours, lower knowledge of MI risk factors was associated with age ≥ 50 years [23]. For normal BMI among both outpatients and public, overweight and obese among public, lower knowledge of MI risk factors was associated with primary education. This is consistent with one study that showed that among both public and outpatients with non-healthy lifestyle behaviours, and among the public with >2 healthy lifestyle behaviours, lower knowledge was associated with primary education [23]. It contradicts the same study that also demonstrated that among public with non-healthy lifestyle behaviours, lower knowledge was associated with secondary education [23]. For those with normal BMI among outpatients and obese among public, it was secondary education. This is in line with this study that showed that among outpatients, lower knowledge of MI risk factors was associated with secondary education [23]. Differences in study’s findings could be due to that one was not adjusted for BMI but for healthy lifestyle behaviours. For those with normal BMI among public, lower knowledge of risk factors was associated with no physical activity, current smokers, and current drinkers while for those obese among public, it was no physical activity. This resonates with that study that showed some of the similar associations among the public [23]. For those with normal BMI, overweight and obese among outpatients, it was history of psychiatric diseases, and family history of heart diseases which resonates with same study [23], except that those obese among outpatients, had also associations with good lifestyle interventions such as non-smoking and non-drinking.

Conclusion

Most of awareness rates and knowledge scores were insufficient even though outpatients had higher awareness and knowledge and MI than the public based on BMI. Results call for more and strategized campaigns targeting the population based on BMI.

However, not all MI symptoms and risk factors included in this study should be weighted equally because some are easily identifiable and more common than others. Other studies have measured knowledge/awareness differently, whereas we used lowest or highest mean score. Some subgroups had small samples, which reduced the knowledge of MI risk factors was associated with age 35-49 years while statistical power to calculate differences. Self-reported information is subject to bias. Finally, there may be differences in demographic factors between responders and non-responders that we cannot elucidate.

Strengths and Limitations

Information in our study was obtained by an open-ended questionnaire among public and outpatients simultaneously. A very high response was obtained and therefore these results represent current knowledge among the two groups in the country. All information contained in the questionnaires was collected through standardized face-to-face interviews. We compared our results with mostly previous open-ended studies for the respective groups.

Ethical Statement

Approval of this study was done by the Ethics Committee of University of Botswana, Ministry of Health and Wellness in Botswana, Health Research and Development Division (ref. no. HPDME: 13/18/1) together with the Regional Ethics Committee, South East, section C (ref. 2018/1121/REK sør-øst A), Norway. The study has been reported according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in cross sectional survey (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the hospitals and DHMTs management, and their staff in greater Gaborone, in addition to the funders for this research study.

Funding

Botswana and Norway governments’ collaboration in the health sector. The funders had no influence in the study methodology, data analysis and interpretation, and producing the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to disclose regarding the content of this article.

Availability of Data and Materials

The datasets used in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for Publication

All authors have read and approved the manuscript for submission.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed substantially in producing this study.

References

- Roth GA, Mensah GA, Johnson CO, Addolorato G, Ammirati E, et al. (2020) Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk factors, 1990-2019: Update from the GBD 2019 study. J Am Coll Cardiol 76:2982-3021. [ Crossref]

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Roth GA, Johnson C, Abajobir A, Abd-Allah F, Abera SF, et al. (2017) Global, regional, and national burden of cardiovascular diseases for 10 causes, 1990 to 2015. J Am Coll Cardiol 70:1–25.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gouda HN, Charlson F, Sorsdahl K, Ahmadzada S, Ferrari AJ, et al. (2019) Burden of non-communicable diseases in sub-Saharan Africa, 1990-2017: Results from the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet Global Health 7:1375-1387.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Institute of health metrics and evaluation. (2021).

- GBD. Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. (2017) Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990-2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 390:1211-1259.

- GBD. DALYs and HALE Collaborators. (2017) Global, regional, and national Disability-Adjusted Life-Years (DALYs) for 333 diseases and injuries and Healthy Life Expectancy (HALE) for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2016: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet390:1260-344.

- GBD Risk Factors Collaborators. (2017) Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990-2016: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet 390:1343-1420.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kumar PJ, Clark ML (2005) Clinical medicine 6th ed. W.B. Saunders.

- Grech ED, Ramsdale DR (2003) Acute coronary syndrome: ST segment elevation myocardial infarction. BMJ 326:1378-1381.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Goff DC, Sellers DE, McGovern PG, Meischke H, Goldberg RJ, et al. (1998) Knowledge of heart attack symptoms in a population survey in the United States: The REACT trial. Arch Intern Med 158:2329-2338.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Donohoe RT, Haefeli K, Moore F (2006) Public perceptions and experiences of myocardial infarction, cardiac arrest and CPR in London. Resuscitation 71:70-79.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bury G, Murphy AW, Power R, Daly S, Mehigan C, et al. (1992) Awareness of heart attack signals and cardiac risk factors among the general public in Dublin. Ir Med J 85:96-97.

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang QT, Hu DY, Yang JG, Zhang SY, Zhang XQ, et al. (2007) Public knowledge of heart attack symptoms in Beijing residents. Chin Med J 120:1587-1591.

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Khan MS, Jafary FH, Faruqui AM, Rasool SI, Hatcher J, et al. (2007) High prevalence of lack of knowledge of symptoms of acute myocardial infarction in Pakistan and its contribution to delayed presentation to the hospital. BMC Public Health 7:284.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Limbu YR, Malla R, Regmi SR, Dahal R, Nakarmi HL, et al. (2006) Public knowledge of heart attack in a Nepalese population survey. Heart Lung 35:164-169.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lutfiyya MN, Lipsky MS, Bales RW, Cha I, McGrath C (2008) Disparities in knowledge of heart attack and stroke symptoms among adult men: An analysis of behavioral risk factor surveillance survey data. J Natl Med Assoc 100:1116-1124.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Greenlund KJ, Keenan NL, Giles WH, Zheng ZJ, Neff L, et al. (2004) Public recognition of major signs and symptoms of heart attack: Seventeen states and the US Virgin Islands, 2001. Am Heart J 147:1010-1016.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fang J, Keenan N, Dai S, Denny C (2008) Disparities in adult awareness of heart attack warning signs and symptoms-14 States 2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 57:175-179.

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tullmann DF, Dracup K (2005) Knowledge of heart attack symptoms in older men and women at risk for acute myocardial infarction. J Cardiopulm Rehabil 25:33-39

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Henriksson C, Larsson M, Arnetz J, Berglin-Jarlov M, Herlitz J, Karlsson JE, et al. (2011) Knowledge and attitudes toward seeking medical care for AMI-symptoms. Int J Cardiol 147:224-227.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Whitaker S, Baldwin T, Tahir M, Choudhry O, Senior A, et al. (2012) Public knowledge of the symptoms of myocardial infarction: A street survey in Birmingham, England. Fam Pract 29:168-173.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hertz JT, Madut DB, Tesha RA, William G, Simmons RA, Galson SW, et al. (2019) Knowledge of myocardial infarction symptoms and perceptions of self-risk in Tanzania. Am Heart J 210:69-74.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ookeditse O, Ookeditse KK, Motswakadikgwa TR, Masilo G, Bogatsu Y, et al. (2024) Age and healthy lifestyle behavior’s disparities and similarities on knowledge of myocardial infarction symptoms and risk factors among public and outpatients in a resource-limited setting, cross-sectional study in greater Gaborone, Botswana. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 24:140.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Obesity and overweight-World Health Organization (WHO).

- Collaborators GB, Arnlov J (2020) Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet 396:1223-1249.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kim DW, Her SH, Park HW, Park MW, Chang K, et al. (2019) Association between body mass index and 1-year outcome after acute myocardial infarction. PloS one 14:217525.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alhuneafat L, Jabri A, Abu Omar Y, Margaria B, Al-Abdouh A, et al. (2022) Relationship between body mass index and outcomes in acute myocardial infarction. J Clin Med Res 14:458-465.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhu J, Su X, Li G, Chen J, Tang B, et al. (2014) The incidence of acute myocardial infarction in relation to overweight and obesity: A meta-analysis. Arch Med Sci 10:855-862.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Matinrazm S, Ladejobi A, Pasupula DK, Javed A, Durrani A, et al. (2018) Effect of body mass index on survival after sudden cardiac arrest. Clin Cardiol 41:46-50.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Aune D, Schlesinger S, Norat T, Riboli E (2018) Body mass index, abdominal fatness, and the risk of sudden cardiac death: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur J Epidemiol 33:711-722.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bucholz EM, Rathore SS, Reid KJ, Jones PG, Chan PS, et al. Body mass index and mortality in acute myocardial infarction patients. Am J Med 125:796-803.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Niedziela J, Hudzik B, Niedziela N, Gasior M, Gierlotka M, et al. (2014) The obesity paradox in acute coronary syndrome: A meta-analysis. Eur J Epidemiol 29:801-812.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Birnbach B, Höpner J, Mikolajczyk R (2020) Cardiac symptom attribution and knowledge of the symptoms of acute myocardial infarction: A systematic review. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 20:445

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gill R, Chow CM (2010) Knowledge of heart disease and stroke among cardiology inpatients and outpatients in a Canadian inner-city urban hospital. Can J Cardiol 26:537-541.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gallagher R, Roach K, Belshaw J, Kirkness A, Warrington D (2013) A pre-test post-test study of a brief educational intervention demonstrates improved knowledge of potential acute myocardial infarction symptoms and appropriate responses in cardiac rehabilitation patients. Aust Crit Care 26:49-54.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mata J, Frank R, Gigerenzer G (2014) Symptom recognition of heart attack and stroke in nine European countries: A representative survey. Health Expect 17:376-387.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McGruder HF, Greenlund KJ, Malarcher AM, Antoine TL, Croft JB, et al. (2008) Racial and ethnic disparities associated with knowledge of symptoms of heart attack and use of 911: National Health Interview Survey, 2001. Ethn Dis 18:192-197.

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fang J, Gillespie C, Keenan NL, Greenlund KJ (2011) Awareness of heart attack symptoms among US adults in 2007, and changes in awareness from 2001 to 2007. Futur Cardiol 7:311-320.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Intas G, Tsolakoglou J, Stergiannis P, Chalari E, Eleni C, et al. (2015) Do Greek citizens have minimum knowledge about heart attack? A Survey. Health Sci J 9:1-6.

- Kim HS, Lee H, Kim K, Park JK, Park KS, et al. (2016) The general public's awareness of early symptoms of and emergency responses to acute myocardial infarction and related factors in South Korea: A national public telephone survey. J Epidemiol 26:233-241.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Quah JLJ, Yap S, Cheah SO, Ng YY, Goh ES, Doctor N, et al. (2014) Knowledge of signs and symptoms of heart attack and stroke among Singapore residents. Biomed Res Int 572425.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Noureddine S, Froelicher ES, Sibai AM, Dakik H (2010) Response to a cardiac event in relation to cardiac knowledge and risk perception in a Lebanese sample: A cross sectional survey. Int J Nurs Stud 47:332-341.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Banharak S, Zahrli T, Matsuo H (2018) Public knowledge about risk factors, symptoms, and first decision-making in response to symptoms of heart attack among lay people. Pacific Rim Int J Nurs Res 22:18-29.

- Song L, Yan HB, Yang JG, Sun YH, Hu DY (2010) Impact of patients' symptom interpretation on care-seeking behaviors of patients with acute myocardial infarction. Chin Med J 123:1840-1845.

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pearlman D, Affleck P, Goldman D (2011) Disparities in awareness of the warning signs and symptoms of a heart attack and stroke among Rhode Island adults. Med Health Rhode Island 94:183-185.

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gao Y, Zhang HJ (2013) The effect of symptoms on prehospital delay time in patients with acute myocardial infarction. J Int Med Res 41:1724-1731.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Abed MA, Ali RMA, Abu Ras MM, Hamdallah FO, Khalil AA, et al. (2015) Symptoms of acute myocardial infarction: A correlational study of the discrepancy between patients' expectations and experiences. IntJ Nurs Stud 52:1591-1599.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Albarqouni L, Smenes K, Meinertz T, Schunkert H, Fang X, et al. (2016) Patients’ knowledge about symptoms and adequate behaviour during acute myocardial infarction and its impact on delay time: Findings from the multicentre MEDEA study. Patient Educ Couns 99:1845-1851.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nicol MB, Thrift AG (2005) Knowledge of risk factors and warning signs of stroke. Vasc Health Risk Manag 1:137-147.

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Groves T (2008) Enhancing the quality and transparency of health research. BMJ 337:718.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Peters RJG, Mehta S, Yusau S (2017) Acute coronary syndromes without ST segment elevation. BMJ 334:1265-1269.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Centre for Diseases Control and Prevention. (2024).

- World Health Organization. www.who.int. (2021).

- Goudevenos JA, Halvorsen S, Hindricks G, Kastrati A, Lenzen MJ, et al. (2018) 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 39:119-177.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Consultation WH (2000) Obesity: Preventing and managing the global epidemic. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 894:1-253.

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- National Institutes of Health (1998) Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults-the evidence report. National Institutes of Health. Obes Res 6:51S-209S.

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gupta V, Dhawan N, Saeed O, Bhoi S (2011) Knowledge of myocardial infarction in sample populations: A comparison of a developed and a developing nation. Trop Med Int Health 16:327.

- Calabrò P, Niccoli G, Gragnano F, Grove EL, Vergallo R, et al. (2019) Are we ready for a gender-specific approach in interventional cardiology? Int J Cardiol 286:226-233.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Citation: Ookeditse O, Ookeditse KK, Motswakadikgwa TR, Masilo G, Bogatsu Y, et al. (2024) Body Mass Index Differences and Parities on Knowledge of Myocardial Infarction among Public and Outpatients in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Cross-Sectional Study in Greater Gaborone, Botswana. J Obes Weight Loss Ther S8:002.

Copyright: © 2024 Ookeditse O, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Usage

- Total views: 777

- [From(publication date): 0-2024 - Dec 20, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 522

- PDF downloads: 255

.png)

): Normal BMI; (

): Normal BMI; ( ): Underweight; (

): Underweight; ( ): Overweight; (

): Overweight; ( ): Obesity.

): Obesity..png)