Determination of Oviposition Preference and Infestation Level of Tuta absoluta on Major Solanaceae Crops Under Glasshouse Conditions in Ethiopia

Received: 13-Nov-2017 / Accepted Date: 27-Nov-2017 / Published Date: 30-Nov-2017 DOI: 10.4172/2329-8863.1000322

Abstract

Tuta absoluta (Meyrick) is a very destructive insect pest with a strong preference for tomato plants. It originates from South America where it has been considered a key pest since the 1980s. It can also attack the aerial parts of tomato, potato, tobacco and some solanaceous weeds. Based on the leaf and fruit-infestation data, four genotypes of tomato (Coshoro, Roman-VF, Galila and Local var.), showed susceptible responses; four genotypes of potato (Jalane, Menagesha, Tolcha and Local var.) showed a tolerant trend and four pepper genotypes (M. Awaze, M. Fana, M. Zala and Local var.), with non-infestation and high resistant, were resulted during 2015-2017. Significant differences were observed, among the genotypes, regarding to the oviposition, in number of eggs/plant. Tomato, showed a maximum oviposition of 62.38%/plant on upper leaf followed by lower leaf 35.72%/plant; while minimum oviposition was recorded to be on flower 0.37% and stem 0.53% per plant, respectively. In contrast, on potato genotypes the maximum ovipostion was recorded on lower leaf as an average 79.63%/plant and 15.11% was recorded on upper leaf; while minimum oviposition were recorded on stem of potato genotypes as an average 1.93%/plant and on all pepper genotype no oviposition was recorded in both years. Variations were found to be significant among dates of observation, regarding to the larval-population and infestation-percentage of the leaf and fruits, during both the study years. There were no significant (P>0.05) differences among each crop varieties. Hence, these present findings are suggest that T. absoluta oviposition behavior is dependent on the host plant preferences among major solanaceae crops and not on varieties of each crop.

Keywords: Infestation; Genotype; Host preferences; Oviposition; Pepper; Potato; Resistant; Susceptible; Tolerance; Tomato; Tuta absoluta

Introduction

Insect pests can reduce vegetable crop yields, increase the costs of their management, and lead to the use of pesticides which ultimately lead to the disruption of existing Integrated Pest Management (IPM) systems [1]. Among the invasive pests, the tomato leafminer, Tuta absoluta (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae), is a devastating pest that develops principally on solanaceous plants throughout South and Central America and Europe [2]. It is a very destructive and an oligophagous pest with a strong preference for tomato; it can also attack the aerial parts of potato, eggplant, tobacco and some solanaceous weeds [3]. It is a multivoltine species, which rapidly develops in favorable environmental conditions, with overlapping life cycles [4]. The tomato leafminer, T. absoluta is one of the most devastating pests of tomato in Ethiopia. This pest was initially reported in Eastern Shawa of Ethiopia in early 2012 [5], and has subsequently spread throughout the country. Since the time of its initial detection, the pest has caused serious damages to tomato in invaded areas, and it is currently considered a key tomato threat to Ethiopia tomato production areas.

The management option of T. absoluta in most South American countries used as chemical insecticides, which was Organophosphates were used at the first time to control T. absoluta [6]. To minimize the use of chemical insecticides modern high resistant cultivars have greater capacity than traditional ones for compensation from insect pest damage, consequently suffering less yield loss. For improved control decisions, farmers thus need to assess the compensatory ability of the crop and severity of crop stress acting on it [7]. However, intensive tomato production with excessive pesticide use has created several pest and environmental problems, as a result, the concept of integrated pest management (IPM) has gained importance over the years. Sources of resistance in the form of resistant cultivars, landraces, accessions, or wild relatives of crop species have been identified for virtually all major pests of all major crops when screenings of sufficient scale have been conducted [8].

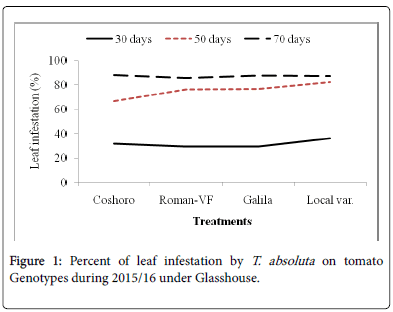

Resistant cultivars paved the way for implementing IPM in many countries [9]. Host-plant resistance is compatible with cultural, biological and chemical control, which can make the IPM system more effective and sustainable [10,11]. IPM programmes have been developed in Ethiopia using resistant cultivars against T. absoluta. Therefore, the present studies were to determine oviposition of T. absoluta and evaluated the infestation level of major solanaceae crop varieties against T. absoluta under glasshouse conditions (Figure 1).

Materials and Methods

Description of the study area

The research was conducted for two consecutive years under glasshouse conditions at Ambo University glasshouse (Figure 2). Ambo is at a geographical coordinate of 8°59'N latitude and 37.85°E longitude with an altitude of 2100 meter above sea level [12]. The temperature of the glasshouse during the study period was 32 ± 2°C.

Experimental design

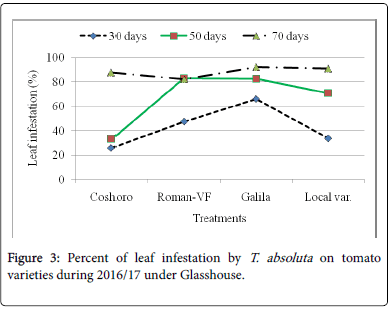

The present study was carried out for two consecutive years using three major Solanaceae crops (tomato, potato and pepper) genotypes against T. absoluta . Seeds of the genotypes were obtained from Melkasa Agricultural Research Centers. The experiment was laid out in Randomized Complete Block Design (RCBD) with three replications (Figure 3). The plants were transplanted into the experimental glasshouse after 40 days. The experimental pots, 20 cm diameters and 25 cm height totally 36 pots were prepared and filled with compost, loam soil and sand soil in the ratio of 1:1:2, respectively. All agronomic practices were performed as required and recommended.

Data collection

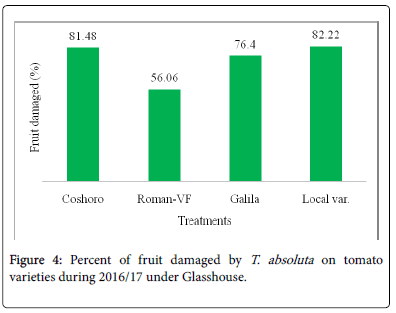

In this study, different parameters were evaluated on sample plants in each treatment. Data were collected randomly from each variety/ line of each replication (Figure 4). Morphological characters such as plant number of leaves per plant, fruit number per plant were recorded at 30, 50 and 70 days after transplanting [13]. Total number of infested leaf, healthy leaf and fruits were counted and percent infestations of T. absoluta was calculated and graded from the mean percentages according to the method of Mukhopadhyay and Mandal [14].

Data analysis

Mean values of each entry from different date after transplanting were analyzed statistically using SAS version 9.1 package computer programme [15].

Results and Discussion

Oviposition of T. absoluta on major solanaceae crops

The present studies, showed that tomato was the primary host for T. absoluta in both 2015/2016 and 2016/2017 (Table 1). On tomato plant, more T. absoluta eggs were laid rather than potato and pepper during the study periods. Eggs were almost found to be laid singly on the upper and lower side of the leaf of tomato and potato crops. On tomato varieties percent oviposition on upper leaves ranged from 62.23 to 67.24% and on lower leaves ranged from 32.01 to 36.80% were recorded during 2015/16 while during 2016/17 it was observed that on upper leaves of all varieties of tomato ranged from 63.96 to 68.09% and on lower leaves from 30.82 to 34.50% were recorded. On the other hands, percent ovipostion of T. absoluta on potato showed on Table 1, it was recorded that from 23.33 to 35.15% on upper leaves and 63.69 to 75.75% on lower leaves during 2015/16 and ranged from 23.21 to 40.08% on upper leaves and 56.49 to 76.80% on lower leaves of all varieties of potato crops. Very few numbers of eggs were laid on stem, buds, flowers and calyxes of the fruits of all varieties of tomato. Larvae were generally found feeding on leaves, creating wide mines giving it a papery appearance and tunneling through the fruits. They were also found boring into the apical buds and the stems. Infested fruits had the small hole closer to the calyxes all varieties of tomato. Finally, we observed that T. absoluta oviposition preferentially occurs on the upper leaf of tomato and lower leaf of potato plants where highest densities of trichomes are found.

| Eggs laid by females/plant | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015/16 | 2016/17 | |||||||

| Treatments | Upper leaf (%) | Lower leaf (%) | Stem (%) |

Flower (%) |

Upper leaf (%) | Lower leaf (%) | Stem (%) | Flower (%) |

| Coshoro | 62.23bc | 36.80c | 0.48 | 0.5 | 67.35a | 31.93c | 0.33 | 0.33 |

| VF-Roman | 66.39ab | 35.97c | 0.49 | 0.23 | 63.96a | 34.35c | 0.53 | 2.17 |

| Galila | 60.88c | 35.41c | 0.27 | 0.68 | 68.09a | 30.82c | 1.09 | 0 |

| Local var. | 67.24a | 32.01c | 0.36 | 0.36 | 64.51a | 34.50c | 1 | 0 |

| Jalane | 23.33e | 73.89a | 2.78 | 0 | 31.75d | 56.49b | 1.75 | 0 |

| Tolcha | 26.84e | 71.31a | 1.85 | 0 | 37.11c | 57.48b | 5.41 | 0 |

| Menagesha | 35.15d | 63.69b | 1.15 | 0 | 40.08c | 59.92b | 0 | 0 |

| Local var. | 23.96e | 75.75a | 0 | 0 | 23.21e | 76.80a | 0 | 0 |

| M. Awaze | 0.0f | 0.0d | 0 | 0 | 0.0f | 0.0d | 0 | 0 |

| M. Fana | 0.0f | 0.0d | 0 | 0 | 0.0f | 0.0d | 0 | 0 |

| M. Zala | 0.0f | 0.0d | 0 | 0 | 0.0f | 0.0d | 0 | 0 |

| Local var. | 0.0f | 0.0d | 0 | 0 | 0.0f | 0.0d | ||

| LSD | 4.9 | 5.73 | 6.44 | 11.91 | ||||

| SE± | 2.89 | 3.39 | 3.8 | 7.03 | ||||

| CV (%) | 9.48 | 9.56 | 11.38 | 21.8 | ||||

Table 1: Mean oviposition preference of T. absoluta on major Solanaceae crops during 2015-2017. Note: Means with the same letter(s) in rows are not significantly different for each other. All treatment effects were highly significant at p

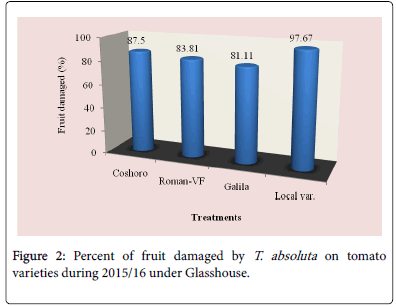

Host plant susceptibility and infestation level

The data presented in Table 2 regarding to the larval population of leaf infestation per plant on major solanaceae crop genotypes of tomato, potato and pepper. The data, on the larval population per plant, leaf infestation and fruit damaged were recorded. The analysis of variance revealed that a significant (P<0.05) differences among the crops and non-significant (P>0.05) differences were observed among varieties of each crops. The results indicated that the maximum leaf infestation was recorded to be 88.14% per plant during 2015/16 and 92.08% during 2016/17 were observed on tomato varieties. As regarding to fruit damaged also no significance differences were recorded among each variety. They were recorded 81.11 to 97.67% during 2015/17 and 56.06 to 82.22% during 2015/17 (Table 1).

| Year I (2015/16) | Year I (2016/17) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trts | Leaf infested (%) | Fruit damaged (%) | Leaf infested (%) | Fruit damaged (%) | ||||

| 30 days | 50 days | 70 days | 90 days | 30 days | 50 days | 70 days | 90 days | |

| Coshoro | 31.88b | 66.62b | 88.14a | 87.50a | 25.98d | 33.29c | 87.68a | 81.48a |

| Roman-VF | 29.53b | 76.20b | 85.75a | 83.81a | 47.60b | 82.14a | 82.96a | 56.06a |

| Galila | 29.53a | 76.40b | 87.78a | 81.11a | 66.09a | 82.55a | 92.08a | 76.40a |

| Local var. | 36.13a | 82.18a | 87.15a | 97.67a | 33.82c | 70.74b | 90.82a | 82.22a |

| Jalane | 9.23c | 21.24c | 24.19b | - | 7.73ef | 19.33c | 24.25b | - |

| Tolcha | 14.42c | 21.94c | 23.87b | - | 8.89ef | 18.62d | 23.50b | - |

| Menagesha | 9.87c | 17.12c | 22.80b | - | 6.35f | 15.27d | 24.43b | - |

| Local var. | 12.14c | 16.06c | 16.17b | - | 12.97e | 17.0d | 20.12b | - |

| M. Awaze | 0.0d | 0.0d | 0.0c | - | 0.0g | 0.0e | 0.0c | - |

| M. Fana | 0.0d | 0.0d | 0.0c | - | 0.0g | 0.0e | 0.0c | - |

| M. Zala | 0.0d | 0.0d | 0.0c | - | 0.0g | 0.0e | 0.0c | - |

| Local var. | 0.0d | 0.0d | 0.0c | - | 0.0g | 0.0e | 0.0c | - |

| LSD | 5.34 | 13.03 | 9.13 | 35.86 | 5.31 | 9.37 | 13.86 | 35.29 |

| SE± | 3.15 | 7.69 | 5.39 | 17.95 | 3.14 | 5.53 | 8.18 | 17.66 |

| CV (%) | 21.9 | 24.43 | 14.84 | 20.87 | 17.97 | 19.54 | 22.07 | 23.85 |

Table 2: Infestation level of T. absoluta on different days of observation on major Solanaceae crop varieties during 2015-2017 under glasshouse conditions. Note: Means with the same letter(s) in rows are not significantly different for each other. All treatment effects were highly significant at p

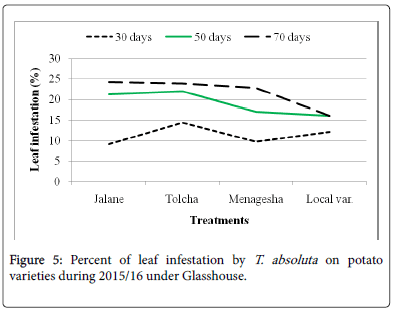

On potato varieties, Jalane, Menagesha, Tolcha and Local var. were found to have tolerance response and did not show significant (P>0.05) differences with one another (Figure 5). The results indicated that the leaf infestation percentage ranging from 16.17% to 24.25% for both years (Table 1). The later mentioned on the pepper cultivars showed non leaf and fruit infestation and non-significant differences with those of pepper cultivars.

Mean population trends at various dates of observations

In both years, the mean population tendencies of T. absoluta on tomato crops were observed. The egg populations were low during the early months of December 15th and high during the end of February. Then it becomes decline gradually starting from the end of February to early march. Again at mid of March it becomes gradually increased till mid-April and then decline slowly to at the end of May it becomes very low. In contrast, the population tendencies of T. absoluta on potato varieties increase gradually from mid-January till at the end of May 29th. These results indicated that during mid-months of December the tomato plants were at vegetative and flowering stages and then matured the ovipositions were declined and the insects were move to potato plants. Non significance differences were found among each tomato and potato varieties. On the other hands, T. absoluta larva did not prefer all pepper varieties (Tables 1-3).

| Mean number of T. absoluta population tendency on different stages at different Months of Observation on major solanaceae crops | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Months | Stages | Coshoro | VF- Roman | Galila | Local var. | Jalane | Tolcha | Menagesha | Local var. | M. Awaze |

M. Fana | M. Zala |

Local var. |

| December | E | 1.75 | 3.25 | 8.75 | 5.25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 15th | L | 1.25 | 3 | 6.25 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| P | 1 | 2.5 | 5.75 | 2.75 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| December | E | 8.25 | 10.75 | 19.25 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 30th | L | 6.75 | 9.25 | 15.25 | 9.25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| P | 5.25 | 7.25 | 11.25 | 5.75 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| January 14th | E | 19.5 | 26.5 | 33.75 | 29.25 | 3.75 | 2.5 | 5.25 | 2.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| L | 17.25 | 20.25 | 22.5 | 20.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| P | 14.25 | 13.25 | 12.75 | 16.25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| January 29th | E | 22.5 | 25.25 | 19.75 | 32 | 2.25 | 6 | 4.25 | 8.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| L | 14.25 | 17.75 | 13.5 | 26.25 | 2 | 5 | 3.25 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| P | 10.25 | 9.75 | 11 | 19.75 | 0 | 3.75 | 2.75 | 2.25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| February 13th | E | 20.67 | 28.5 | 23.25 | 24.25 | 8.25 | 12.5 | 13.25 | 10.75 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| L | 13 | 18.25 | 14.75 | 20.25 | 3.75 | 5.75 | 7.25 | 6.75 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| P | 10.75 | 10 | 7.25 | 13.75 | 1.25 | 2.5 | 3.75 | 3.25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| February 28th | E | 24.25 | 32.25 | 35 | 27.25 | 10.75 | 15.25 | 8.5 | 16.25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| L | 14.75 | 18.25 | 18.25 | 22 | 7 | 9.5 | 3.25 | 9.25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| P | 6.5 | 8.75 | 7.5 | 14.75 | 3.25 | 4.75 | 1.25 | 4.75 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| March | E | 8.25 | 9.75 | 13.25 | 12.75 | 7.25 | 19.5 | 14.25 | 10.75 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 15th | L | 11.75 | 18.25 | 22.25 | 18.25 | 12.5 | 8.25 | 9.5 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| P | 6.5 | 11.5 | 14.5 | 12 | 5.75 | 4.25 | 6.25 | 4.75 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| March 30th | E | 16.25 | 22.75 | 18.25 | 19 | 26.25 | 32.25 | 29.5 | 25.75 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| L | 9.25 | 14.5 | 10 | 13.5 | 14.25 | 17.25 | 20.25 | 21 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| P | 5.5 | 4.75 | 5.25 | 9.75 | 9 | 8.5 | 10 | 14.25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| E | 26.75 | 28.25 | 21.5 | 27.25 | 32.5 | 40.5 | 37.25 | 29 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| April 14th | L | 14 | 15.75 | 17 | 22.5 | 14.25 | 24.25 | 18.25 | 25.75 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| P | 6 | 9 | 12.25 | 10 | 12.25 | 12.25 | 8.5 | 18.75 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| E | 17.25 | 19.75 | 13.25 | 16.25 | 38 | 37.75 | 42.5 | 35.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| April 29th | L | 14.75 | 13.75 | 8.25 | 11.75 | 16.75 | 21.5 | 18.25 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| P | 8.75 | 6 | 5.75 | 6.25 | 6 | 15 | 8.25 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| E | 3.75 | 6.25 | 5.5 | 7.25 | 47.25 | 31.5 | 29.5 | 40.25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| May 14th | L | 0 | 2.5 | 3 | 3.25 | 21.75 | 15.5 | 17.25 | 33.25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| P | 0 | 0 | 1.25 | 2.75 | 14.25 | 8.25 | 11.5 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| May 29th | E | 2.25 | 4.5 | 0 | 3 | 40.75 | 36.25 | 31.75 | 48 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| L | 1.75 | 0 | 2. 50 | 2.25 | 28.25 | 19.75 | 22.25 | 22.25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| P | 1 | 0 | 1.25 | 0 | 14.75 | 11.25 | 16.25 | 14.75 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

Table 3: Mean population tendency on major solanaceae crops at different Months of observation during 2015-2017 under glasshouse. Note: E=No of eggs/plant L=No of larvae/plant P=No of pupae/plant.

Discussion

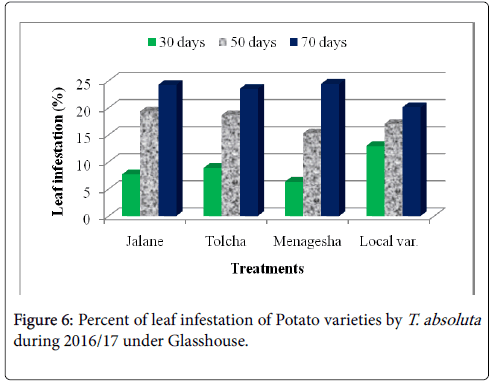

This finding shows that the oviposition site choice by female T. absoluta is likely to be dependent on the highest densities of trichomes and infestation level. A good assumption could be that tomato leafminer infestation could be resulted in a high favorable and susceptible hosts of tomato varieties rather than potato and pepper and compared to the non-infested pepper genotypes sites are unlikely to support the growth and development of a newly laid egg because of very less trichomes are observed (Figure 6). Our result was disagreed with the previous work of Muniappan [16], he was stated that Capsicum annum (Pepper) was host preference by T. absoluta . Though, high larvae density and infestation level of T. absoluta on tomato plants were observed. Indeed, the number of larvae and infestation level on the potato plant were lower as compared with the infestation levels in tomato plants. Therefore, female egg laying preferences are restricted to the least infested plant and oviposition seems to be stimulated at a certain density of trichomes, as the number of eggs was found to be statistically similar between each plant varieties.

Under similar conditions, tomato leafminer females may have developed a system of host plant assessment manifested by moderate oviposition level on varieties of potato, increased infestation level during the maturity of tomato varieties and also, gradually increased infestation level in the absence of all tomato varieties. But T. absoluta was non-preferentially oviposited of any pepper genotypes during the glasshouse study even no host chooses. However, many insect species mark the host patch during egg lay to regulate the oviposition site selection [17]. Our findings confirm the laboratory studies of Thomas et al. [2] they suggest that female oviposition response could be more sophisticated than would be expected from a simple intraspecific competition model based on the detection of previous infestation. It is generally assumed that larval survivability depends on the female’s oviposition choice because most lepidopteran larvae are unable to move to an alternative food source [18,19]. We found differences in terms of total number of eggs laid on tomato varieties, but no difference in terms each crop varieties. It is also true that similar trends were observed among potato varieties. Considering T. absoluta antagonists may provide more explanations about this behavior according to Thomas et al. [2]. In their natural environment, Zappala et al. [20] reported that solanaceous leafminers are significantly affected by many factors that keep them at endemic levels. In contrast, tomato leafminer are not easily affected by many factors because of high generation and host specificity.

Conclusions and Recommendations

This finding suggests that T. absoluta oviposition behavior is dependent on the host plant preferences and did not on varieties of each crop. The other factors like densities of trichomes may have played a vital role in the tomato leafminer oviposition behavior. Maximum larval population per plant and percent infestation of the leaf and fruits, were observed on tomato varieties; while, the minimum larval population and leaf infestation were found on potato varieties and non-infestation was found on pepper varieties, as such to be comparatively susceptible, tolerance and resistant, respectively. These results provide useful information on integrated pest management strategies of T. absoluta . Further studies are needed on more solanaceae crops and effect of trichomes on oviposition under field condition.

References

- Thomas MB (1999) Ecological approaches and the development of ‘truly integrated’ pest management. Proc Natl Acad Sci 96: 5944-5951.

- Thomas B, Lara DB, David D, Pauline L, Rudy C, et al. (2014) Infestation Level Influences Oviposition Site Selection in the Tomato Leafminer Tuta absoluta (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae). J of Insects 5: 877-884.

- Notz AP (1992) Distribution of eggs and larvae of Scrobipalpula absoluta in potato plants. Magazine of the Faculty of Agronomy (Maracay) 18: 425-432.

- Guenaoui Y, Bensaad F, Ouezzani K (2010) First experiences in managing tomato leaf miner Tuta absoluta Meyrick (Lepidoptera:Gelechiidae) in the Northwest area of the country. Preliminary studies in biological control by use of indigenous natural enemies. Phytoma Espana 217: 112-113.

- Gashawbeza A, Abiy F (2013) Occurrence of a new leaf mining and fruit boring moth of tomato, Tuta absoluta (Meyric) (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) in Ethiopia. Pest Management J of Ethiopia 16: 57-61.

- Lietti MM, Botto E, Alzogaray RA (2005) Insecticide Resistance in Argentine Populations of Tuta absoluta (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae). Neotropical Entomology 34: 113-119.

- Litsinger JA (2009) When is a rice insect a pest: yield loss and the green revolution. In: Peshin R, Dhawan AK (eds.), Integrated Pest Management: Innovation-Development Process. Springer Science & Business Media, Dordrecht, Netherlands, pp: 391-498.

- Kennedy GG, Barbour JD (1992) Resistance variation in natural and managed systems. In: Fritz RS, Simms EL (eds.), Plant Resistance to Herbivores and Pathogens: Ecology, Evolution, and Genetics. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp: 13-41.

- Panda N (2003) Host plant resistance and insect pest management. In: Subrahmanyam B, Ramamurthy VV, Singh VS (eds.), Frontier Areas of Entomological Research. Entomological Society.

- Wilde G (2002) Arthopod host plant resistant crops. In:Â Pimentel D (ed.), Encyclopedia of Pest Management. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, pp: 33-35.

- Wiseman BR (1994) Plant resistance to insects in integrated pest management. Plant Dis 12: 927-932.

- Briggs P, Blatt B (2012) Ethiopia: Bradt Travel Guides. Guilford, Connecticut: The Globe Pequot Press Inc.

- Khanan UKS, Hossain M, Ahmed N, Uddin MM, Hossain MS (2003) Varietal Screening of Tomato to Tomato Fruit borer, Helicoverpa armigera (Hub.) and Associated Tomato Plant Characterstics. Pak J Biol Sci 6: 421-413.

- Mukhoppardhay A, Mandal A (1994) Screening of brinjal (Solanum melongena) for resistance to Major insect pests. Indian J Agril Sci 64: 798-803.

- SAS (2009) Statistical Analysis System Software. Ver 9.1. SAS Institute InC., Carry. NC.

- Renwick JAA (1989) Chemical ecology of oviposition in phytophagous insects. Experientia 45: 223-228.

- Awmack CS, Leather SR (2002) Host plant quality and fecundity in herbivorous insects. Ann Rev Entomol 47:Â 817-844.

- Gripenberg S, Mayhew PJ, Parnell M, Roslin T (2010) A meta-analysis of preference-performance relationships in phytophagous insects. Ecol Lett 13: 383-393.

- Zappalà L, Biondi A, Alma A, Al-Jboory IJ, Arnò J, et al. (2013) Natural enemies of the South American moth, Tuta absoluta, in Europe, North Africa and Middle-East, and their potential use in pest control strategies. J Pest Sci 86: 635-647.

Citation: Shiberu T, Getu E (2017) Determination of Oviposition Preference and Infestation Level of Tuta absoluta on Major Solanaceae Crops Under Glasshouse Conditions in Ethiopia. Adv Crop Sci Tech 5:322. DOI: 10.4172/2329-8863.1000322

Copyright: © 2017 Shiberu T, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 6242

- [From(publication date): 0-2017 - Dec 06, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 5224

- PDF downloads: 1018