Research Article Open Access

Domestic Violence as a Risk Factor for Children Ending up Sleeping in the Streets of Post-War South Sudan

Owen Ndoromo, Karin Österman* and Kaj Björkqvist

Department of Social Sciences, Peace and Conflict Research, Developmental Psychology, Åbo Akademi University, P.O.B. 311, 65101 Vasa, Finland

- *Corresponding Author:

- Karin Österman

Department of Social Sciences, Peace and Conflict Research

Developmental Psychology

Åbo Akademi University, P.O.B. 311

65101 Vasa, Finland

Tel: 358-6-3247468

E-mail: karin.osterman@abo.fi

Received Date: Jan 25, 2017; Accepted Date: Feb 17, 2017; Published Date: Feb 23, 2017

Citation: Ndoromo O, Österman K, Björkqvist K (2017) Domestic Violence as a Risk Factor for Children Ending up Sleeping in the Streets of Post-War South Sudan. J Child Adolesc Behav 5: 335. doi:10.4172/2375-4494.1000335

Copyright: © 2017 Ndoromo O, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Child and Adolescent Behavior

Abstract

The study investigated the life of children in the street in post-war South Sudan. A main objective was to examine whether children who slept in the streets although they had parents they could go home to had been victimised more from domestic violence than children working in the street by day but spending the nights at home. A sample of 197 children found in the streets of Juba and Yei, including 8 children who were sex-workers, filled in a questionnaire. In the sample, 43.7% slept in the street. Among children who slept in the street, 81% had one or both parents alive, and among children who had enough food at home, 31.1% anyway chose to sleep in the street. Children who slept in the streets although they had parents had been hit with the hand at home significantly more often, and their mothers had hit their fathers significantly more often in comparison to those who slept at home. Their parents also had significantly more alcohol problems. Of the children who slept in the street, 48% had severe injuries, and 10% had extremely severe injuries. Domestic violence, including physical aggression between parents, and physical punishment of children, as well as alcohol problems of parents were found to be associated with children not only working but also ending up sleeping in the streets of South Sudan.

Keywords

Street children; Sleeping in the streets; Domestic violence; Physical punishment; South Sudan

Introduction

By day, many children work and spend their time in the streets of South Sudan, but not all of them return home in the evening regardless of the risk for violence and exploitation connected with sleeping in streets or market places. A central aim of the study was to examine whether there were children who were not orphans but had parents they could go home to, who did not only work in the streets by day but also remained sleeping there at night. If such children were found, a further aim was to analyse whether they had been victimised more from domestic violence than children who spent the night at home. Other aspects of life in the streets, such as sexual abuse, drugs, and work, were also examined. In South Sudan, like in many other developing countries, children sleeping in the street is a severe problem. Consequences of sleeping in the street are in many cases fatal for the children as they easily become victims of physical violence and sexual abuse. Children also are deprived of a family, which hampers their social development.

Furthermore, sleeping in the street is a human rights issue. The African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights (1998) [1] has strongly condemned all forms of violence against children. The problem is widespread all over the developing world and deserves due attention. Findings from South Sudan might be relevant also for other countries.

Domestic violence associated with children sleeping in the streets

Multiple factors have been considered as contributing to children living in the streets. In a review of studies on street children in the developing world, poverty, and abuse, were related to children choosing to live in the streets [2]. Street children in South Africa have themselves mentioned family violence, alcoholism, and poverty as reasons for leaving their home [3]. It has in fact been pointed out that poverty alone is not the only reason; abuse in the home can be a significant factor [4]. Physical and psychological abuse has been shown to predict running away from home [5-7].

A descriptive epidemiology of the prevalence of street children in the capital Juba has been published by Poni-Gore et al. [8]. They drew the conclusion that among other factors, one of the reasons why the percentage of street girls was lower than that of boys was that girls preferred to endure difficulties of life at home rather than in the streets.

Recently, an increasing number of studies suggest that domestic violence might be one of the decisive factors pushing children to the streets. In a study conducted in Cameroon [9], 61% of the street children mentioned maltreatment by parents or relatives as the reason for deserting their home. The family’s economic situation also contributed, but to a lesser degree. Likewise, in a study of street children in Bangladesh [10], it was shown that a low level of cohesion in the family, and repeated multiple forms of violence inflicted on children by parents were the most important underlying factors. Poverty alone could only partially explain the phenomenon of children migrating to the streets. According to a survey conducted in seven different parts of South Sudan, nearly half of the street children had been driven to the streets as a result of a combination of cruelty, lack of parental care, and poverty [11]. In another study of street living children in Juba, South Sudan [12], the children reported that domestic violence, lack of parental care, and parents’ alcohol problems were more difficult to cope with than life in the street. The same reasons for children to migrate to the street were also identified by adults taking part in the study.

Groenendijk and Veldwijk [13] examined life stories collected among of sex workers in Juba, and found that violence in the family was reported in all the stories. Many girls also stated explicitly that they had run away from their family because of violence committed towards them by fathers or other male relatives. Two other recent studies from South Sudan mention mistreatment or abuse at home among the reasons for children ending up in the streets [14,15].

Furthermore, a survey carried out in Khartoum, Sudan, showed that 27% of street boys and 40% of street girls had been physically abused at home, and that 18% of the boys and 17% of the girls had been thrown out from their family home [16]. Some of the children reported extremely violent physical abuse in their home. Many drawings and stories of street children in the same study were also related to mistreatment at home.

In a study carried out in neighbouring Uganda, it was found that the most common reason for children migrating to the streets (34.6%) was mistreatment by parents or guardians [17].

Children of South Sudan

The historical context of the war and its impact on children has been described in detail by Belay Tefera [18]. The signing of the comprehensive peace agreement of 2005 brought an end to the longest war in Africa, and South Sudan gained its independence in 2011. It has been estimated that the war killed approximately 2.5 million, and displaced 4.5 million people [19]. The long conflict affected children very severely, and many became orphans. Following the peace agreement, many displaced South Sudanese started to return home; among them, children were the largest group [20]. Of the children less than five years of age, 21% were found to be malnourished, and eight percent were affected by severe malnutrition [21]. As a result, many children went to the streets searching for food. According to Safi and Akol [22], the exact number of street children in South Sudan is not known, but efforts are currently being made to establish a database including numbers of street children and orphans [23]. It has been estimated that the number of homeless children in the capital Juba alone rose from 1,200 in 2009 to more than 3,000 in 2013 [24].

Armed conflicts have been associated with an escalation in domestic violence in a country [25,26]. Though the war is over in South Sudan, and the 2008 act of child protection has been adopted, domestic violence and sexual abuse of children are still widespread. Even though the constitution of South Sudan prohibits all kinds of corporal punishment, it is still practiced daily, both in families and schools. Another significant problem facing girls in Muslim families of South Sudan is the practice of female genital mutilation [27], with some girls running away from their parents in order to escape it and ending up living in the street [28].

Methods

Sample

A total of 197 children, 71 girls and 126 boys, between six and 17 years of age, took part in the study conducted in 2014. A questionnaire was filled in by those children who could read and write, the researcher helped the others to fill it in. The children were found in Juba (n=140), the capital of South Sudan, and in the smaller town of Yei (n=57) about 100 miles southwest of Juba. The girls (M=14.6 years, SD=2.0) were significantly older than the boys (M=13.6 years, SD=2.4) [t(195)=2.74, p=0.007]. There was no significant age difference between children from the two cities. Nine of the girls worked in a brothel; their age range was between 13 and 17 years.

Tribal belonging of the children was established by the first author who is of South Sudanese origin. The largest group of children belonged to the Kakwa tribe (51.3%), which originates from the South Western part of South Sudan. The following tribes were also represented: Bari, Pojulu, Latuko, Baka, Mundari, Denka, Avukaya, Murle, Taposa, Nuba, Zande, Murru, Kukku, Mundu, Didinga, Peri, Acholi, Mandi, Lokoya, Balanda, and Ugandan. Tribal belonging of one child could not be established. Of the children, 97% were Christians, and two percent were Muslims.

Instrument

The questionnaire was filled in with each child individually. The following topics were covered: family background and education, daily life in the streets (e.g., work, drugs), injuries, war experiences, victimisation from domestic violence, and expectations for the future. Injuries were rated by the researcher on a four-point scale (no injuries=0, small=1, severe=2, extremely severe=3). Two groups were formed based on the children’s responses to the question “Where do you sleep?” (at home/in the street).

Victimisation from physical punishment at home was measured with three questions: how often has an adult at home (a) pulled your hair, (b) hit you with the hand, and (c) hit you with an object? Witnessing of interpersonal violence between parents was measured with two questions: how often (a) did your father hit your mother, and (b) did your mother hit your father? Responses regarding physical punishment and parental aggressive behaviours were given on a four point scale (never=0, sometimes=1, often=2, very often=3). Questions concerning shortage of food at home, parents’ alcohol problems, and sexual abuse were yes/no answers. Life stories of six randomly chosen children, expectations for the future, and drawings made by the children are presented.

Procedure

A pilot investigation was carried out in 2013, after that the current questionnaire was constructed. The field work in South Sudan was carried out during the period of June ? October 2014. Prior to the study, cooperation had been established with Juba National University. Since research permissions were necessary in order to deal with the security interventions that were expected to take place during the field work, local authorities in the towns Juba and Yei provided written consent for the investigation.

The researcher visited places like Juba market, Konykonyo market, Gumbo market, Gudele market, and Jebel market where street children were expected to be found. First, he observed the children at length, learning their habits. Children in the street commonly form small groups with a leader. The researcher would then established a friendly contact with the leader and ask if he would like to fill in a questionnaire. After that, other group members turned up encouraged by the leader.

The data were collected sitting in the street, in market places, bus stations, or sleeping places of the children (Figure 1) in a way that the conversation could not be overheard by others. The researcher informed them about the study and encouraged them to ask questions about it. The children who volunteered subsequently filled in the questionnaire individually. The researcher filled in the questionnaire for those who could not do it themselves. The questionnaire was in English, the data collection was additionally supported by explanations in seven different Bari-languages, and Arabic.

In the end, the children were presented with paper and pencils, and asked if they would like to make a drawing. When the drawing was finished, the children were asked if they wanted to explain what the drawing was about.

Description of the social setting in the area of data collection>

During day hours, street children could be observed moving around in groups of three to five. Their clothes were dirty and worn out. Many of them sniffed on a yellow rubber solution container that they kept in their mouth, others smoked cigarettes. They clearly feared people and kept at a distance from others. Most of the street children observed in Juba city and Yei were boys. In the evening some children returned home to share what they had earned with their parents, others stayed in the streets. In Juba city, there were girls making their living as sex workers in Jebel market, Konyokonyo market, and Gumbo market. They were sitting by the doors of their shelters, waiting and calling out to men passing by. Most of the sex workers were from other countries, few were South Sudanese. Some were under-aged. In Jebel market, sex with an older girl costed 30 South Sudanese pounds, while sex with an under-aged girl costed 50.

Most of the street children have to work to support themselves, but particularly in Juba city, some of the already grown-up street children are involved in criminal activities. They slept during day time, and sent young street children to steel food and money. In the afternoon, young street children brought to them what they had collected. At night, grown-up street children are sometimes hired to rob, or even kill people. Cases of robbing and killing were common in Juba. This has led to bad relationships between the street children and the police authorities, and also with the rest of the inhabitants.

Ethical considerations

The data collection was made in an environment that was safe and familiar to the children. The children were carefully informed that taking part in the study was completely voluntary and that their identities would not be disclosed at any time.

When under-aged children are filling in questionnaires, written consent from parents is usually a requirement. In this case, written consent from parents or caretakers could not be obtained, since some children where orphans, and in many cases parents were illiterate. Some children had run away from their homes due to abuse from their parents.

Under specific circumstances when parental written consent is not a reasonable requirement, the US Department of Health and Human Services regulation allows for waiving parental permission. A waiver of parental consent regarding research involving minors is applicable according to the US Department of Health and Human Services of the United States under 46.116 if: (a) the research involves minimal risk, (b) the waiver will not adversely affect the rights and welfare of subjects, (c) the research could not practicably be carried out without the waiver, and (d) where appropriate, subjects are provided with additional information [29]. The present study qualifies for all four conditions.

Consequently, children were informed very carefully about the study. Only those who by their own will stated that they wanted to fill in a questionnaire were given one. Verbal consent was given by each child. Otherwise, the research as such does not pose any ethical problem since it only involves filling in anonymous questionnaires. The study was given ethical clearance by the board for research ethics at Åbo Akademi University. The project was carried out in accordance with the Personal Data Act, Ministry of Justice Finland. In addition, Juba National University endorsed the project, and permissions for the research were granted from both the city of Juba and the city of Yei, where the data collections took place.

Results

Of the children in the whole sample, 62.4% (n=123) had both parents alive, 28.9% (n=57) had only one parent alive, and 8.6% (n=17) were orphans. A significantly higher percentage of the girls had lost their mother (23.9% vs. 11.1%) [χ2(1)=5.64, p=0.024]; significantly more girls than boys were orphans (18.3% vs . 3.2%) [χ2(1)=13.19, p<0.001]. Among the eight girls who were sex workers, six had both parents alive, only one was an orphan. Of the children, 60.2% were cleaning restaurants and lodges, 20.9% were selling things in the market, 8.2% were sex workers, 3.6% were pickpockets, and 3.1% had no work (Table 1, Figure 2). School attendance was highest (84.6%) among children who had both parents alive. The percentages were lower for the other groups: for those with only the father alive it was 78.6%, and for those with only the mother alive 62.8%; for orphans, it was 47.1%. Of the children, 24.4% (n=48) had witnessed someone being killed; 65% had a relative who had been killed, 22.3% (n=44) had nightmares about the war, and 90.9% (n=179) were afraid that the war would come back.

| Girls (n) | Boys (n) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cleaning restaurants and lodges | 59.2% (42) | 60.8% (76) | 60.2% |

| Selling things in the market | 18.3% (13) | 22.4% (28) | 20.9% |

| Sex worker | 14.1% (10) | 4.8% (6) | 8.2% |

| Pickpocket | 4.2% (3) | 3.2% (4) | 3.6% |

| No work | 2.8% (2) | 3.2% (4) | 3.1% |

| Shoes shiner | 0.0% | 3.2% (4) | 2.0% |

| Asking money from people | 0.0% | 1.6% (2) | 1.0% |

| Selling tea | 1.4% (1) | 0.8% (1) | 1.0% |

Table 1: Percentages of girls and boys in the sample doing different kinds of work.

Two groups: Children who slept in the streets and children who slept at home.

Children who work in the streets by day but return home in the evening are commonly referred to as children on the street; children who also sleep in the streets are referred to as children of the street. In the sample of this study, 56.3% of the children slept at home, 28.9% slept in a market place, and 10.2% in verandas of shops (Table 2). Among the children who slept in the street, 44.2% had both parents alive, 30.2% had only the mother alive, 7.0% had only the father alive, while 18.6% were orphans. This means that 81.4% of those sleeping in the street were not orphans; they had either one or both parents alive.

| Percentage of Girls (n) | Percentage of Boys (n) | Percentage of All (n) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| At home | 60.6% (43) | 54.0% (68) | 56.3% (111) |

| In the market place | 32.4% (23) | 27.0% (34) | 28.9% (57) |

| Verandas of shops | 4.2% (3) | 13.5% (17) | 10.2% (20) |

| Under bridges | 1.4% (1) | 4.8% (6) | 3.6% (7) |

| In a lodge | 1.4% (1) | 0.8% (1) | 1.0% (2) |

Table 2: Places where the children slept.

Drugs

Drugs were used by 8.5% of the girls and 16.8% of the boys; there was a tendency towards a difference here [χ2(1)=2.66, p =0.076]. Drugs were used by 9.0% of the children who slept at home, and by 20.0% of the children who slept in the streets; the difference was significant [χ2(1)=4.90, p=0.023].

Injuries

Extremely severe injuries were found in 10.5% of the children who slept in the streets; this was significantly more than among the children who slept at home (2.7%) [t(195)=5.43, p ≤0.001]. Of the children who slept in the street, 47.7% had severe injuries, compared to 18.0% of those who slept at home. Injuries of boys were significantly more serious than those of girls [t(195)=3.09, p=0.002]. The injuries were most frequently found on arms or legs and were the result of beatings by parents, other street children, or by a boss at the workplace. No medical assistance was available for the children, and injuries were often badly infected.

Not enough food at home

Of the whole sample, 62.4% (n=123) had not had enough food at home. About one-third of those who had enough food at home (31.1%) (n=23) still slept in the streets. This finding suggests that there may be other factors related to family life besides poverty that discourages children from going home to their parents where there would have food to eat.

Parents’ alcohol problems, and physical violence between parents

Of the total sample, 53.3% of the children reported that their parents had alcohol problems (Figure 3). There was no significant difference between girls and boys. Among children who slept at home, 44.2% reported that their parents had alcohol problems, while among the children who did not sleep at home, 60.4% reported alcohol problems; the difference was significant [χ2(1)=5.09, p =0.017].

The children reported that 84.3% had (or had had) fathers who hit their wife sometimes; 74.6% of the mothers were reported to have hit their husband sometimes (Figure 4). Husbands had hit their wives significantly more often than the wives had hit their husbands [t(195)=3.20, p=0.002].

Physical and sexual abuse of children

In the total sample, 94.4% of the children had been hit with a stick (Figure 5); 19.8% had been hit with the hand, and 4.5% had been hit with a wire. A tendency was found for boys to have been hit with an object more often than girls [t(195)=1.87, p=0.064]. No significant sex difference was found for how often girls and boys had been hair pulled or hit with the hand. Of all the children, 46.2% had been physically abused by their boss at work, 30.5% by their mother, 11.2% by their father, 7.6% by clients, 3.6% by elder street children, and 0.5% by the police. Of the eight children who worked as sex workers, three had been physically abused by their mother, three by their boss, and two by a client.

Among the girls who were not sex workers, 44.4% (n=28) had been forced by their boss at their workplace to do sexual things, and one girl had been forced to do it at home by a parent. Among the boys 29.4% (n=37) had been forced by their boss at their workplace to do sexual things, no boy had been forced to do that at home.

When the 16 sex-workers in the sample were compared to the other children regarding risk factors, no differences were found between the groups for how often they did not have enough food at home, physical aggression between parents, or physical punishment of the child.

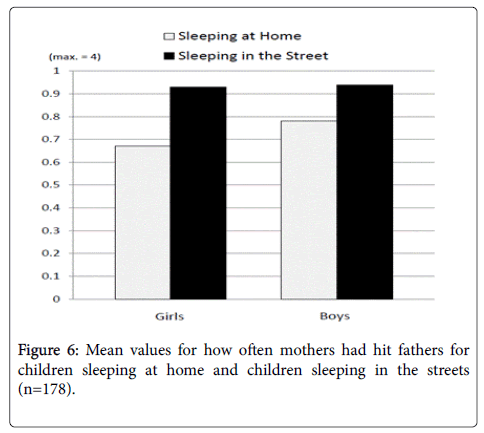

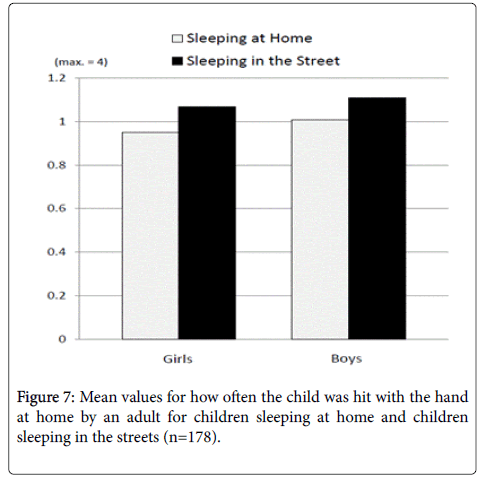

The association between sleeping in the streets and domestic violence

A grouping variable was constructed dividing the children into two groups; those who stated that they slept at home (n=109), and those who slept in the streets (n=69). A multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was conducted including only children who had one or two parents alive, for the sake of compatibility, orphans were not included in this analysis. Children’s group belonging served as independent variable, and three kinds of domestic violence served as dependent variables: father hits mother, mother hits father, and the child gets hit with the hand by adults at home. The multivariate test was significant for group belonging [F(3, 174)=4.47, p =0.005, ηp2=0.072].

The univariate analyses showed a significant difference between children sleeping in the street and children sleeping at home for mother hits father [F(1, 176)=8.69, p =0.004, ηp2=0.047] (Figure 6), and for the child gets hit with the hand [F(1, 176)=5.96, p =0.016, ηp2=0.033] (Figure 7), but not for father hits mother. The fact that husbands hitting wives was very common (in 84% of the cases) probably contributed to the finding that fathers hitting mothers did not account for a significant group difference. Children sleeping in the street also reported that their mothers had hit their fathers significantly more often than did those of the children who stayed in the streets by day but went home to sleep in the night. Children sleeping in the street had also been significantly more often hit with the hand by an adult at home as compared to those going home to sleep.

What will you do when you grow up?

When asked what they will do when they grow up, 25.4% of the girls and 17.5% of the boys said they wanted to become a medical doctor. The second most popular occupation for girls was teacher (16.9%), and for boys, driver (15.1%). Four girls and seven boys wanted to become president.

Drawings

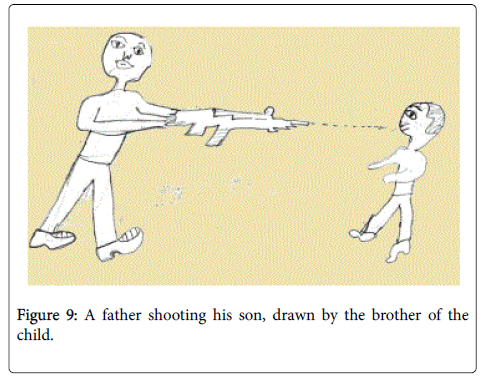

After filling in the questionnaire, each child was offered to draw a picture of something he/she was afraid of, or liked. The most common theme was guns; guns were depicted in 26.9% (n=43) of the drawings, and shooting of people was present in 24.3% (n=39). A man killing his wife was depicted in seven drawings (Figure 8), and in one drawing, a father shot his own son (Figure 9). Altogether, killing and guns made up 56.2% (n=90) of all the drawings. Domestic violence was depicted in 9.4% (n=15) of the drawings. Drawings of guns and of drinking too much alcohol were made more frequently by girls (guns: 26.8% vs. 19.0%¸ and alcohol: 11.3% vs. 2.4%), while boys made more drawings of peace than girls (6.3% vs. 1.4%).

Discussion

Domestic violence as a risk factor for sleeping in the street

Sleeping in the street is dangerous: street children in Juba have reported that night time, when they have to find a safe place to sleep, is the most difficult part of the day [12]. The main objective of the present study was to examine reasons behind why some children, who are not orphans, despite the dangers involved sleep in the streets of cities in South Sudan, while other children who also work in the street return to their homes. The study examined family-related factors associated to some children sleeping in the street.

Although the link between domestic violence and children turning to the streets seems to be quite established in novels, fiction and the media, few scientific studies have so far presented empirical evidence of the connection. Many studies on street children mention domestic violence and abuse as a reason for children moving to the streets, but most of these studies are of a purely qualitative nature.

The present study found that among the children who slept in the streets, 81% had one or both parents alive, and that one in three of children who had enough food at home still continued to sleep in the street. On the other hand, there were also children who stayed with their parents although they starved at home. This suggests that some factors discourage children who have parents from going home for the night. Besides poverty, one reason why children choose not to sleep at home could be domestic violence.

Children who did not sleep at home, although they had parents, were found to have been hit at home significantly more often than those who still went home in the evenings. The mothers of these children were also found to have hit the fathers significantly more often as compared to children who stayed in the streets by day, but went home in the night. Also alcohol problems were found to be significantly more common among the parents of these children, in comparison with those who went home in the evening. Thus, it may be concluded that not only shortage of food at home, but also domestic violence, including both physical violence between parents and physical punishment of children, in addition to parents’ alcohol abuse, were factors associated with children ending up sleeping in the streets of South Sudan.

Methodological issues and limitations of the study

It was found that although the children who took part in the study had no prior experience responding to questionnaires, they did not have difficulties in responding to items with graded response alternatives (e.g., never, seldom, sometimes, often, very often). Domestic violence was measured with variables at interval level.

A limitation of the study was that the question of whether there was enough food at home or not was provided with only “yes” or “no” response alternatives. It could also have been measured with interval level responses.

Due to the extremely difficult circumstances in the country, children were sampled from two cities only. Further research would benefit from including more locations and also a bigger sample. The link between domestic violence and children starting to sleep in the streets should be examined further, also in other countries.

Another variable that could have been studied in more depth is the effect of having a stepmother or a stepfather. The level of domestic violence against children in families were one of the parents is not a biological one has not so far been compared with intact families. Some children also live with other relatives, the risk of being victimised in such a homes might be very high.

The main challenge for the project was the political situation in South Sudan. In January 2014 when the project started, the situation was far from stable. The route between Juba and Yei required six hours driving, the roads were poor, and there was a danger of landmines. Since most children did not go to school during the war, street children only speak their mother tongue. The fact that the main researcher himself was a native South Sudanese having knowledge of the local languages, culture, and customs, enabled him to approach the children in a culturally appropriate manner. The researcher wandered the streets of Juba and Yei, first observing the children, and then making friends with those who were not too shy. This method was crucial for the collecting of the data, since street children are shy and often reluctant to talk to strangers. At later points in time, when the researcher happened to meet the children, they usually greeted him as a friend and protector. Many also asked for his assistance to help them out of the harsh life in the streets.

Implications of the study

Multiple reasons contribute to children living in the street, domestic violence could be one of the major ones, but it has still not been studied in depth. This study suggests that poverty makes children work in the streets by day, but domestic violence makes many of them also sleep there at night.

The authorities of South Sudan, like many international organisations, try to gather the street children and place them in orphanage centers. However, more effort should be made to deal also with the prevalence of domestic violence. In order to reduce the number of children sleeping in the streets, information and awareness training is needed for parents and others involved in child care. If the rate of domestic violence were reduced, the number of children forced to a life in the streets could be expected to decline.

Based on the results of this study, it is recommended that programmes for reducing domestic violence are implemented in order to lessen the steady influx of children to the streets. Non-governmental organisations working in South Sudan might also provide information campaigns about the detrimental effect of domestic violence, and especially about the physical punishment of children.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to show their gratitude to Professor Onesimo Yabang, and Dr. Leben Nelson Moro at the University of Juba, as well as Charles Lumago Peter; without their support the field research in Africa would not have been possible.

Financial support

The study was supported by grants from The Nordic Africa Institute, Uppsala, Sweden, and Högskolestiftelsen i Österbotten, Vasa, Finland.

References

- The African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights (1998) Prevention and eradication of violence against women and children. Addendum to the SADC declaration on gender and development.

- Aptekar L (1994) Street children in the developing world: a review of their condition. Cross-Cultural Res 28: 195-224.

- Le Roux J (1996) Street children in South Africa: Findings from interviews on the background of street children in Pretoria, South Africa. Adolescence 31: 423.

- Lalor KJ (1999) Street children: A comparative perspective. Child Abuse Negl 23: 759-770.

- Kim MJ, Tajima EA, Herrenkohl TI, Huang B (2009) Early child maltreatment, runaway youths, and risk of delinquency and victimization in adolescence: A mediational model. Soc Work Res 33: 19-28.

- Feitel B, Margetson N, Chamas J, Lipman C (1992) Psychosocial background and behavioral and emotional disorders of homeless and runaway youth. Hosp Community Psychiatr 43: 155-159.

- Hammer H, Finkelhor D, Sedlak AJ (2002) Runaway/thrownaway children: National estimates and characteristics. U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

- Poni-Gore R, Loro RL, Oryem E, Iro RE, Reec WB, et al. (2015) Phenomena of street children life in Juba, the capital of South Sudan, a problem attributed to long civil war in Sudan. J Community Med Health Educ 5: 1-8.

- Matchinda B1 (1999) The impact of home background on the decision of children to run away: the case of Yaounde City street children in Cameroon. Child Abuse Negl 23: 245-255.

- Conticini A, Hulme D (2007) Escaping violence, seeking freedom: Why children in Bangladesh migrate to the street. Dev Change 38: 201-227.

- Madut ML (2011) South Sudan: Domestic violence drives children onto the streets. Sudan Tribune.

- Enfants du Monde, Droits de l’Homme (2009) Survey on children in street situation in Juba. EMDH, Paris, France.

- Groenendijk C, Veldwijk J (2011) Behind the papyrus and mabaati: sexual exploitation and abuse in Juba, South Sudan. Confident Children out of Conflict.

- Belay Tefera K (2015b) The situation of street children in selected cities of South Sudan: magnitude, causes, and effects. Eastern Africa Soc Sci Res Rev 31: 63-87.

- Belay Tefera K (2009) The situation of street children in Southern Sudan and educational implications. Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology, the Government of Southern Sudan.

- Plummer ML, Kudrati M, Yousif NDEH (2007) Beginning street life: Factors contributing to children working and living on the streets of Khartoum, Sudan. Child Youth Serv Rev 29: 1520-1536.

- Young L (2004) Journeys to the street: the complex migration geographies of Ugandan street children. Geoforum 35: 471-488.

- Belay Tefera K (2015a) Armed conflict, violation of child rights, and implications for change. J Psychol Psychother 5: 202.

- The International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) (2011) South Sudan. First anniversary of independence. Time to act for peace and human rights protection.

- UN (2011) Building a better future: Education for an independent South Sudan. Education For All Global Monitoring Report Policy Paper. United Nations.

- UNICEF (2012) UNICEF in South Sudan: Unite for children. United Nations International Children’s Emergence Fund.

- Safi M, Akol SM (2013) The problem of street children is a national problem that needs a national solution. Gender Minister.

- Edwards C (2013) South Sudan establishes data base on homeless children. South Sudan News.

- Mogga A (2013) Number of homeless children in Juba up sharply, NGO Says. Voice of America.

- Byrne B, Marcus R, Powers-Stevens T (1996) Gender, conflict and development. Volume II: Case studies: Cambodia; Rwanda; Kosovo; Algeria; Somalia; Guatemala and Eritrea. Ministry of Foreign Affairs, The Netherlands.

- Wilkens A (2010) Links between domestic violence and armed conflict. Report from a field trip in Lebanon, March 7-17. Stockholm, Sweden: Kvinna till Kvinna.

- Islam MM, Uddin MM (2001) Female circumcision in Sudan: future prospects and strategies for eradication. Int Family Planning Perspectives 27: 71-76.

- Merrild I (2011) Female genital mutilation in Sudan: the complexities of eradication. Aguilar MI (Edn) Current Issues in Religion and Politics II. Centre for the Study of Religion and Politics (CSRP) of the University of St. Andrews, Scotland, UK.

- Northwestern University Institutional Review Board (2016) Waiver or alteration of the requirements for obtaining informed consent. Chicago, IL: Northwestern University.

Relevant Topics

- Adolescent Anxiety

- Adult Psychology

- Adult Sexual Behavior

- Anger Management

- Autism

- Behaviour

- Child Anxiety

- Child Health

- Child Mental Health

- Child Psychology

- Children Behavior

- Children Development

- Counselling

- Depression Disorders

- Digital Media Impact

- Eating disorder

- Mental Health Interventions

- Neuroscience

- Obeys Children

- Parental Care

- Risky Behavior

- Social-Emotional Learning (SEL)

- Societal Influence

- Trauma-Informed Care

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 7880

- [From(publication date):

February-2017 - Aug 29, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 6816

- PDF downloads : 1064