Epidemiology of the Diabetic Foot Infection in a Tertiary Care Hospital in the Lebanon: A Retrospective Study between 2000 and 2011

Received: 20-Sep-2018 / Accepted Date: 01-Oct-2018 / Published Date: 15-Oct-2018 DOI: 10.4172/2332-0877.1000381

Keywords: Diabetes mellitus; Infection; Epidemiology

Introduction

Diabetic foot infection (DFI) is a serious public health concern complicated by a high rate of amputation and long hospitalization stay, even in high-income countries [1]. Causing high morbidity and deterioration in fragile diabetic patients, DFI are nowadays the leading cause of hospital bed occupancy in diabetic population. The severity of these cases is due to altered immune response, advanced peripheral arteriopathy and neuropathy along with altered foot anatomy attenuating the pain protective reflex and the local immunity favoring the dissemination of the infection [2]. The infection complicates a foot chronic ulcer worsening its management especially when combined with osteitis and arteriopathy raising the risk of amputation with severe prognosis [3,4]. Furthermore, the DFI represent an increasing financial burden due to the rising number of infected patients [5]. This study is one of the few analyses in Lebanon and the Middle East region looking into the epidemiologic aspects of the DFI in the Lebanese society: Demographics, clinical presentation, microbiology and resistance pattern of the infection and its management.

Materials and Method

This is a retrospective monocentric epidemiological study of DFIs done in a tertiary care hospital in Beyrouth between November 2010 and April 2011. Data were obtained from the hospital charts of DFI admitted to our tertiary care hospital from January 2000 to Mars 2011. The inclusion criteria were: diabetic patients, age ≥ 18 years and grade 2 to 4 DFI (IDSA classification). A total of 167 patients were eligible to this study.

Data collection

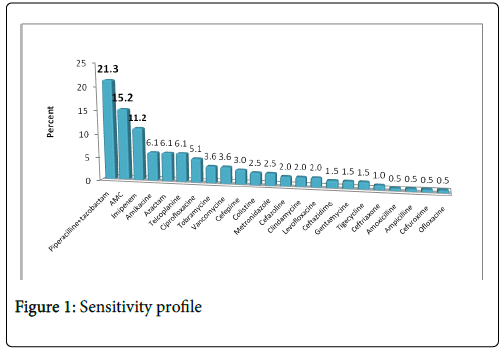

The studied population characteristics combined the following: patients demographics, clinical features (comorbidities, history of amputation and diabetes mellitus complications), infections characteristics (microorganisms, sensitivity profile (Figure 1) and presence of osteitis) and treatment features (antibiotherapy, debridement surgery, arterial bypass and amputation).

Statistical analysis

Data were collected on Excel 2007 and analyzed using SPSS and XLSTAT versions. Descriptive analysis of the population is given as median with standard deviation and in percentage. Pearson's chisquared test (χ2 ) and comparison of two independent variables. P value of <0.05 is considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient’s demographics (Table 1)

The median age of DFI patients admitted to our tertiary care facility is 66 years. The prevalence of foot ulcerations rises with age with a maximal incidence between 70 and 75 years. The sex ratio M/F is 3/1. Male median age is 65 years with 2 young patients of 35 years admitted for foot ulcers. As to female patients, DFIs appear later on in life (69 years).

| Patients demographics | Patients (n [%]) | Median ± SD (interval) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 66.41 ± 12.07 [35-92] | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 123 (73.65) | |

| Female | 44 (26.35) | |

| Diabetes mellitus (DM) duration | 19.62 ± 10.03 [0.083-50] | |

| HbA1C | ||

| <7%: Good glycemic control | 33 (20.75) | |

| >7%: Bad glycemic control | 126 (79.25) | |

| Type of DM | ||

| Type 1 | 3 (1.89) | |

| Type 2 | 153 (96.22) | |

| Others | 3 (1.89) | |

| DM complications | ||

| Peripheral neuropathy* | 94 (72.3)/36 (27.69) | |

| Peripheral arteriopathy* | 120 (73.17)/44 (26.83) | |

| Coronary heart diseases* | 79 (49.69)/80 (50.31) | |

| Retinopathy* | 73 (48.67)/77 (51.33) | |

| Nephropathy* | 71 (47.65)/78 (52.35) | |

| Co-morbidities | ||

| Arterial hypertension* | 96 (60.38)/63 (39.62) | |

| Dyslipidemia* | 77 (48.73)/71 (51.25) | |

| Tobacco smoking | ||

| Actual smoker | 49 (32.45) | |

| Ex-smoker | 43 (28.48) | |

| Nonsmoker | 59 (39.07) | |

| Previous amputations* | 73 (47.79)/83 (53.21) | |

Table 1: Hospitalized DFI patient demographics.

Clinical features

As for diabetes mellitus, DFI seem to develop in Lebanese patients after 20 years of progression of DM approximately (19.61 ± 1.87) with extremes of 1 month and 50 years of DM diagnosis. HbA1C>7% is found in 79% of patients with DFI indicating a poor diabetic control. 96% pf the patients are of type II DM 28.9% are treated with oral antidiabetic medication (ADM), 51.56% with insulin alone (long acting insulin in 37.7%) and 15.54% treated with a combination of oral ADM and insulin. Among those treated with oral ADM, 50% had an association of sulfamides with metformin. Lower limbs arteriopathy was the most frequent risk factor associated with DFI present in 73.2% of cases. 31% of patients had already undergone an arterial bypass surgery. Peripheral neuropathy is present in 72.8% of DFIs cases clinically presenting as numbness, paraesthesia to severe pain, burning sensation or electrical sensations. Coronaropathy is present in 49.7% of DFI patients clinically presenting as heart failure or myocardial infarcts among which 34% had undertaken a coronary angioplasty or coronary artery bypass surgery. Retinal arteriopathy is present in 47.7% of patients with cases of blindness. Finally, 47.7% had nephropathy sometimes with end stage renal disease.

Comorbidities

Arterial hypertension is found in 60.4% of Lebanese patients with DFI and dyslipidaemia in 48.7%. Tobacco smoking does not seem to be correlated to the development of DFI: 32.5% of DFI patient smoke, 28.5% stopped smoking since >2 years and 39.1% do not smoke.

Amputations

47.79% of hospitalized DFI patients had one or more minor or major foot amputations in their past medical history.

Microbiology of infection (Table 2)

Cellulitis is the most described clinical feature. Radiological findings for osteitis are simultaneous revealed in 31.7%. We describe 11 cases of sepsis, 2 septic shocks necessitating intensive care admissions with one fatal outcome.

| Microorganism | Isolate number | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 45 | 19.15 |

| Escherichia coli | 28 | 11.91 |

| Staphyloccocus aureus | 26 | 11.06 |

| Enteroccocus fecalis | 26 | 11.06 |

| Proteus mirabilis | 20 | 8.51 |

| Group B Beta-Hemolytic Streptococcus | 15 | 6.38 |

| Enterobacter cloacae | 11 | 4.68 |

| Morganella morganii | 9 | 3.83 |

| Citrobacter freundii | 8 | 3.4 |

| Enteroccocus faecium | 5 | 2.13 |

| Klebsiella oxytoca | 5 | 2.13 |

| Enterobacter aerogenes | 4 | 1.7 |

| Klebsiella pneumonia | 4 | 1.7 |

| Pseudomonas spp | 4 | 1.7 |

| Non typable Streptococcus | 4 | 1.7 |

| Citrobacter diversus/amalonaticus | 3 | 1.28 |

| Polymicrobial culture | 3 | 1.28 |

| Serratia marcesens | 3 | 1.28 |

| Staphyloccocus coagulase negative | 3 | 1.28 |

| Candida | 2 | 0.85 |

| Providencia rettgeri | 2 | 0.85 |

| Acinetobacter baumanii | 1 | 0.43 |

| Citrobacter koseri | 1 | 0.43 |

| Enterobacter Sakazakii | 1 | 0.43 |

| Serratia liquefaciens | 1 | 0.43 |

| Group C Beta-Hemolytic Streptococcus | 1 | 0.43 |

Table 2: Microbiology of the DFI population study.

In almost half of the cases (54.26%), the infection was plurimicrobial. The distribution of the causative microorganisms is listed in table 2. Most frequent microorganisms are: Gram negative bacilli: P. aeruginosa (119%), E. coli (12%) and P. mirabilis (9%) and Gram-positive cocci: S. aureus (11%) and E. fecalis (11%).

Resistance patterns (Table 3)

| Beta laclams | Quinolones* | TMPSX * | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitive | Penicillinase | Cephalosporinase | IRT1 | ESBL2 | |||

| Escherichia coli | 2 (7.1) | 9 (37.5) | 5 (21.4) | 2 (7.1) | 8 (28.6) | 6 (21.4)/20 (78.6) | 9 (35.7)/ 17 (64.3) |

| Proteus mirabilis | 9 (42.9) | 6 (28.6) | 4 (21.4) | 1 (7.1) | 0 | 17 (85.7)/3 (14.3) | 10 (50)/ 10 (50) |

| Enterobacter | 1 (9.1) | 0 | 11 (72.7) | 0 | 3 (18.2) | 15 (100)/0 | 12 (81.8)/ 3 (18.2) |

| Citrobacter freundii | 0 | 3 (27.3) | 6 (54.5) | 0 | 2 (18.2) | 9 (81.8)/2 (18.2) | 8 (72.7)/ 3 (27.3) |

| Morganella morganii | 0 | 0 | 9 (100) | 0 | 0 | 2 (75)/ 7 (25) | 0/ 9 (100) |

| Klebsiella | 0 | 6 (80) | 0 | 0 | 2 (20) | 5 (60)/3 (40) | 5 (60)/ 3 (40) |

| Serratia marcesens | 0 | 0 | 3 (100) | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.67)/ 1 (0.33) | 2 (0.67)/ 1 (0.33) |

| Global resistance | - | 24 (26.09) | 38 (41.3) | 3 (3.26) | 15 (16.3) | 36 (39.13) | 44 (47.83) |

Table 3: Betalactam, trimrthoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMPSX) and quinolone sensitivity profile of the enterobateriacae of DFIs in the Lebanese diabetic population.

Isolated enterobacteriacae showed resistance to one or more betalactamin molecule in 86.96% of cases, to quinolones in 39.13% and to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in 47.83%. 16.3% of Enterobacteriacae secrete an extended spectrum beta-lactamase.

6 among 42 isolated pseudomonas multi MDR isolates were still sensitive to colistin as shown in Table 4.

| Piperacilline | Aztreonam | Cefepime | Imipenem | Fluoroquinolones |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 (22.2%) | 16 (37%) | 13 (30.8%) | 11 (25.9%) | 7 (37%) |

Table 4: DFIs pseudomonas isolates sensitivity profile (isolates total number=42).

Seven out of 25 isolates (29.4%) of staphylococcus were methicillin resistant (MRSA). Table 5 shows the enterococci sensitivity pattern to aminoglycosides.

| Low level of resistance | High level of resistance to kanamycine | High level of resistance to streptomycine | High level of resistance to gentamicine | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enteroccocus fecalis | 8 (28%) | 10 (36%) | 8 (26%) | 2 (8%) |

| Enteroccocus faecium | 3 (37.5%) | 2 (25%) | 2 (25%) | 1 (12.5%) |

Table 5: Enterococcus fecalis and fecium resistance profile to aminoglycosides (total number of E. fecalis isolates=26 and E. faecium =5)

Management of the DFI (Graphic 1)

Empirical antibiotherapy later adjusted according to the sensitivity profile is initially instituted (Graphic 1). The most commonly used molecules were: piperacillin-tazobactam (21%), amoxicillineclavulanate (15.2%) and imipenem (11.3%).

Surgical debridement is done in 59.6% and arterial bypass in 26.3%. Amputation rate in this cohort of DFI reached 36.3% going from simple procedure (toe resection) to major amputations (foot or leg or lower limb amputations). Risk factors for amputation include previous amputations (p=0.0059) and arteriopathy (p=0.039)

Discussion

The demographics of the Lebanese diabetic patients admitted for management of DFIs appear like those described in the European [6,7] and American [8] studies. As to the Arab countries, the rare data show DFI appearing early in the course of the disease: Median of 50.5 ± 10.9 years [9] in Egypt and 57.3 ± 6.32 [10] in Bahrain. Only Kuwaiti data were close to Lebanese ones with 61 ± 1.7 years [11]. The maximal hospitalization prevalence was for those patients aging between 70 and 75 years. The rate of the feet ulcers prevalence increases with age with a maximal prevalence after 75 years [12]. Men are infected more frequently and earlier than women who develop DFI later in their lives and less frequently. This later finding was confirmed by Reiber et al showing a male predominance of 75% of the total cases and by Lavery’s case-control study [13]. DFI appears approximately after 20 years of the initial diagnosis of DM in the Lebanese population. This finding is comparable to the results in the French OPIDIA study where diabetic patients were hospitalized for DFI after 17.5 ± 11.1 years of diabetes mellitus. HbA1C levels >7% in the Lebanese general diabetic population (79%) is higher than that of the study population (68.8%). In addition, this study confirms that DFI result from many physiopathologic mechanisms mainly 2 major factors: Peripheral arteriopathy (PA) and neuropathy. PA is widely detected in the Lebanese diabetic population (73.2%), which is higher than international data (46% according to Lavery and 46.1% according to the OPIDIA study). Microbiology of DFI in this study revealed different results than the published data affirming the gram-positive predominance mainly S. aureus [3,14-19]. In fact, we found P. aeruginosa to be the most frequent microorganism isolated from the deep cultures, followed by E. coli then S. aureus and E. fecalis . Therefore, aerobic gram-negative bacteria are the most frequent bacteria in this cohort of Lebanese DFIs. Pseudomonas was also frequently isolated in studies from Malaysia and Nepal. A retrospective analysis of clinical specimens taken from 194 Malaysian patients with diabetic foot infections over a 12-month period from July 1, 2004 to June 30, 2005. 287 pathogens were isolated from 194 patients, an average of 1.47 organisms per lesion: The most frequently isolated pathogens were Gram-negative bacteria (52%), including Proteus spp . (28%), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (25%), Klebsiellapneumoniae (15%) and Escherichia coli (9%). Gram-positive bacteria accounted for 45% of all bacterial isolates. Staphylococcus aureus was predominant (44%) followed by Group B streptococci (25%) and Enterococcus spp. (9%) [20]. In Nepal, diabetic polyneuropathy was found to be common in (51.1%) in patients with DFIs and the most frequent bacterial isolate were Staphylococcus aureus (38.4%), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (17.5%), and Proteus (14%) [21].

Conclusion

DFI in the Lebanese population is a disease of male prevalence in their sixties (median 66 years of age). Women are affected less frequently, and diabetic complications appear lately in their lives. DFI develops nearly 20 years of diabetes progression and is closely related to a bad glycemic control. Risk factors include frequently the classical triad of neuropathy, arteriopathy and minor traumas that causes ulcerations leading to the DFI. PA is a major factor of the complications of DFI having a detrimental effect in the genesis of infection and severe prognosis. Neuropathy and the loss of the protective reflexes and pain play a crucial role in the development of the foot ulcer. DFIs is commonly seen with other diabetes mellitus complications as retinopathy, nephropathy and coronary heart disease. As to the comorbidities, arterial hypertension seems very frequent (60.4%) followed by dyslipidemia (48.7%) in the Lebanese diabetic population. Tobacco smoking strangely doesn’t seem to be related to DFI. Microbiologically, gram negative bacteria were the first two most frequent cause of DFI: P. aeruginosa grew in 19% of the cases followed by E. coli at 12%. S. aureus , the leading bacteria in the international literature, grew only in 11% of the cultures similar to E. fecalis followed by P. mirabilis at 9%. Osteitis is found in 31.2% of patients. Management of DFIs was multidisciplinary associating IV antibiotherapy, surgical debridement and arterial bypass surgeries when indicated. The most prescribed antibacterial molecule was: Piperacillin-tazobactam and amoxicillin-clavulanic acid and imipenem. Amputations were performed in 36.6% of patients driven mainly by the severity of the infection, the advanced arteriopathy and history of prior amputations.

References

- Boulton AJM, Vileikyte L, Ragnarson-Tennvall G, Apelqvist J (2005) The global burden of diabetic foot disease. Lancet 366: 1719-1724.

- Ha Van G, Heurtier A, Bourgeon M, Marty L, Menou P, et al. (2000) Pied diabétique. Encycl Méd Chir (Éditions Scientifiques et Médicales Elsevier SAS, Paris, tous droits réservés), Podologie 27: 16.

- Recommandations pour la pratique clinique. Prise en charge du pied diabétique infecté. Texte long. Médecine et maladies infectieuses 37 (2007) 26-50.

- Malgrange D (2008) Physiopathology of the diabetic foot. La revue de médecine interne 29: S231-S237.

- Keith Bowering C (2001) Diabetic foot ulcers. Can Fam Physician 47: 1007-1016.

- Prompers L, Huijberts M, Apelqvist J,Jude E, Piaggesi A, Bakker K, et al. (2007) High prevalence of ischaemia, infection and serious comorbidity in patients with diabetic foot disease in Europe. Baseline results from the Eurodiale study. Diabetologia 50: 18-25.

- Gershater MA, Löndahl M, Nyberg P, Larsson J, Thörne J, et al. (2009) Complexity of factors related to outcome of neuropathic and neuroischaemic/ischaemic diabetic foot ulcers: a cohort study. Diabetologia 52: 398-407.

- Lavery LA, Armstrong DG, Wunderlich RP, Tredwell J, Boulton AJ (2003) Diabetic Foot Syndrome: Evaluating the prevalence and incidence of foot pathology in Mexican Americans and non-Hispanic whites from a diabetes disease management cohort. Diabetes Care 26: 1435-1438.

- El-Nahas MR, Gawish HMS, Tarshoby MM, State OI, Boulton AJM (2008) The prevalence of risk factors for foot ulceration in Egyptian diabetic patients. Pract. Diabetes Int 25: 362–366

- Al-Mahroos F, Al-Roomi K (2007) Diabetic neuropathy, foot ulceration, peripheral vascular disease and potential risk factors among patients with diabetes in Bahrain: A nationwide primary care diabetes clinic-based study. Ann Saudi Med 27: 25-31.

- Abdulrazak A, Bitar ZI, Al-Shamali AA, Mobasher LA (2005) Bacteriological study of diabetic foot infections. J Diabetes Complications 19:3 138-141.

- Richard JL, Schuldiner S (2008) Épidémiologie du pied diabétique. Rev Med Interne Suppl 2: S222-S230.

- Lavery LA, Armstrong DG, Vela SA, Quebedeaux TL, Fleischli JG (1998) Practical criteria for screening patients at high risk for diabetic foot ulceration. Arch Intern Med 158: 157-162.

- Richard JL, Lavigne JP, Got I, Hartemann A, Malgrange D, et al. (2010) Management of patients hospitalized for diabetic foot infection: Results of the French OPIDIA study. Diabetes Metab 37: 208-215.

- Lipsky BA, Berendt AR, Deery HG, Embil HNM, Joseph WS, et al. (2004) Diagnosis and treatment of diabetic foot infection. Clin Infect Dis 39: 885-910.

- Esposito S, Leone S, Noviello S, Fiore M, Ianniello I, et al. (2008) Foot infections in diabetes (DFIs) in the outpatient setting: an Italian multicentre observational survey. Diabet Med 25: 979-984.

- Candel González FJ, Alramadan M, Matesanz M, Diaz A, González-Romo F, et al. (2003) Infections in diabetic foot ulcers. Eur J Intern Med 14: 341-343.

- Ge Y, MacDonald D, Hait H, Lipsky B, Zasloff M, et al. (2002) Microbiological profile of infected diabetic foot ulcers. Diabet Med 19: 1032-1035.

- Citron DM, Goldstein EJC, Merriam CV, Lipsky BA, Abramson BA (2007) Bacteriology of moderate to severe diabetic foot infections and in vitro activity of antimicrobial agents. J Clin Microbiol 45: 2819–2828.

- Raja NS (2007) Microbiology of diabetic foot infections in a teaching hospital in Malaysia: A retrospective study of 194 cases. J MicrobiolImmunol infect 40: 39-44.

- Sharma VK, Khadka PB, Joshi A, Sharma R (2006) Common pathogens isolated in diabetic foot infection in Bir Hospital. Kathmandu Univ Med J 4: 295-301.

Citation: Choucair J, Saliba G, Chehata N, Nasnas R, Saad NR (2018) Epidemiology of the Diabetic Foot Infection in a Tertiary Care Hospital in the Lebanon: A Retrospective Study between 2000 and 2011. J Infect Dis Ther 6: 382. DOI: 10.4172/2332-0877.1000381

Copyright: © 2018 Choucair J, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 4088

- [From(publication date): 0-2018 - Dec 11, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 3218

- PDF downloads: 870