Review Article Open Access

"From Quality to Access to Justice: Improving the Functioning of European Judicial Systems"

Nadia Carboni*IRSIG-CNR (National Research Council of Italy) 00393473090107, Italy

- *Corresponding Author:

- Nadia Carboni

IRSIG-CNR (National Research Council of Italy)

00393473090107, Italy

E-mail: nadia.carboni@irsig.cnr.it

Received Date: June 24, 2014; Accepted Date: September 23, 2014; Published Date: September 29, 2014

Citation: Carboni N (2014) “From Quality to Access to Justice: Improving the Functioning of European Judicial Systems”. J Civil Legal Sci 3:131. doi:10.4172/2169-0170.1000131

Copyright: © 2014 Carboni N. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Civil & Legal Sciences

Abstract

The articles researches on policies and measures to improve access to justice and, as a consequence, the quality and functioning of the European judicial systems. By depicting the main policy reform trajectories related to the citizens’ access to justice across Europe, the paper deals with the participative experiences in Sweden; the alternative dispute resolution mechanisms in the gender equality and antidiscrimination law, and the ICTs support to access to justice at the European level.

Keywords

Access to justice; E-justice; Citizens; Gender equality; Quality of justice

Introduction

The most recent comparative studies in the public administration field [1-4] highlight a deep transformation of the public sector in Western democracies during the last three decades. The introduction and the adoption of the private sector assumptions, rationality, procedures and tools according to the New Public Management (NPM) and post-NPM paradigms have increasingly changed public organizations [5]. These paradigms have also been embraced in the administration of justice, inspiring a number of attempts to evaluate and improve the functioning of courts [6-8].

However, the design principles advanced by NPM have been criticized by the public value school [9,10] that highlighted the contrasts between the NPM principles and the values that a public administration should support. This argument can be retrieved in the justice system evaluation literature where some authors [11] highlighted the frictions between the efficacy-oriented tenets of the NPM School and the values that justice systems should support as the equal “access to justice”. As an example, the introduction of ICT in the justice systems, as the NPM approach argues, may translate in a disparity of accessibility between the more and less technologically literated users.

Within the public value perspective, a special attention is given to access to justice, as one of the key indicators of quality of justice. The citizens’ access to justice is a tricky issue for improving individuals and business’ rights to a fair trial. At the EU level, and more specifically at the level of trans-border cases, the lack of statistics available and the difficulty to provide up-to-dated information to citizens about their own rights is a serious problem and needs to be solved in order to give better services in the justice field.

The paper investigates the extent to which judicial reforms have affected (and are affecting) the level of citizens’ access to justice, by empirical accounts of the main changes to judicial systems across Europe. The role of European networks (i.e. CEPEJ, CCJE, ENCJ, etc.) has been especially active to make courts more effective and accountable to European citizens.

The paper focuses also on the participation of citizens and principal users to the decisions that affect the service provided by Courts. The participative experiences that foresee the involvement of Court staff at any level together with main court users as lawyers and citizens will be taken into account. An example of this approach, are the participative experiences implemented in some Swedish courts [12]. These can be considered best practices of modernization and improvement of service through deliberation, improvement of the access of citizens to the organization of courts and judicial proceedings, inclusiveness [13,14] and involvement of all actors at any level.

The paper is structured as follows. The first part deals with the concept and the definition of access to justice by focusing on the information side: more information to citizens equally means more and better access. The second part faces with the main policy reform trajectories related to the citizens’ access to justice across Europe; best practices are sorted out in order to identify guidelines for improving access to justice, as final result of case studies analysis.

Definition of Access to Justice: More Information, Better Access

“Access to justice” has come increasingly to the fore in the last decades, becoming indeed, the leitmotiv of the recent wave of judicial reforms all over the world. Such a concept is usually associated with human rights: “access to justice is a basic human right as well as an indispensable means to combat poverty, prevent and resolve conflicts” [15]. “Access to justice” refers to the right of an individual to seek (both substantially and procedurally) an unbiased remedy within the judicial system. There are strong links between establishing democratic governance, reducing poverty and securing access to justice [15]. Democratic governance is undermined where access to justice for all citizens (irrespective of gender, race, religion, age, class or creed) is absent. Lack of access to justice limits the effectiveness of poverty reduction and democratic governance programs by undermining participation, transparency and accountability.

Within the justice administration discourse, access to court relates to easiness to find the courthouse and specific offices or courtrooms within it, opening hours, the presence of physical and language barriers, attention of the personnel to the court user needs, availability of forms to be filled [16].

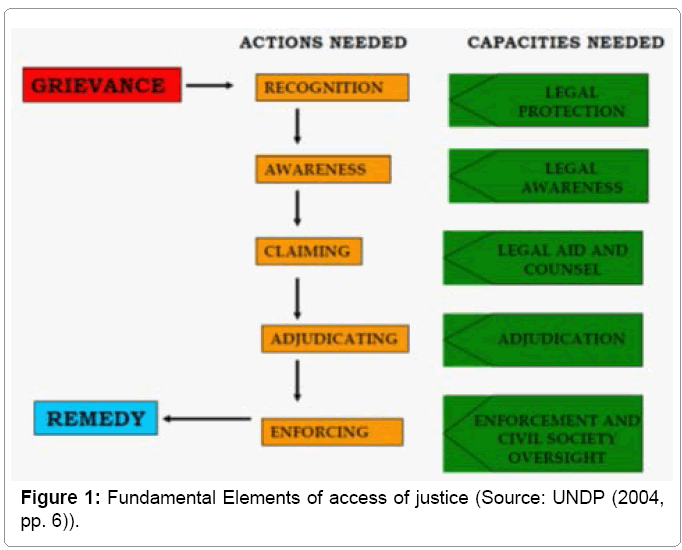

However, access to justice through courts is a much broader concept, which involves more than just court access. It relates to the problem of allowing the claim-holders to be able to claim their rights in court and receive a judicial decision which is fair and of good quality, within a reasonable time and at a reasonable cost. While alternative actions to the access to court (such as marches, pacific protests, media and political mobilization) may result in positive outcomes, they indeed may lead to an erosion of public trust and confidence in the justice system. It is therefore imperative for courts and justice systems to address access to justice in order to improve it. In order to investigate how, it can help to reflect on the barriers that potential and actual court users must confront to get access to justice. The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) practice note on “Access to Justice” identifies a number of barriers to access to justice. From the user’s perspective, the justice system is frequently weakened by [15]:

1. Long delays; prohibitive costs of using the system; lack of available and affordable legal representation, that is reliable and has integrity; abuse of authority and powers, resulting in unlawful searches, seizures, detention and imprisonment; and weak enforcement of laws and implementation of orders and decrees.

2. Severe limitations in existing remedies provided either by law or in practice. Most legal systems fail to provide remedies that are preventive, timely, non-discriminatory, adequate, just and deterrent.

3. Gender bias and other barriers in the law and legal systems: inadequacies in existing laws effectively fail to protect women, children, poor and other disadvantaged people, including those with disabilities and low levels of literacy.

4. Lack of de facto protection, especially for women, children, and men in prisons or centres of detention.

5. Lack of adequate information about what is supposed to exist under the law, what prevails in practice, and limited popular knowledge of rights.

6. Lack of adequate legal aid systems.

7. Limited public participation in reform programs.

8. Excessive number of laws.

9. Formalistic and expensive legal procedures (in criminal and civil litigation and in administrative board procedures).

10. Avoidance of the legal system due to economic reasons, fear, or a sense of futility of purpose (Figure 1).

Among the main obstacles to access to justice, the “legal awareness”, that is the access to understandable rules, is of major importance. The first way to make judicial institutions more accessible is to introduce general measures to inform the public about court’s activities [17]. The lack of statistics available to the public and the lack of information provided to citizens about their own rights is a serious problem.

Above all, citizens should receive appropriate info on the organization of public authorities and the conditions in which the laws are drafted. It is just as important for citizens to know how judicial institutions work. Access to justice perceived as the access to information played a pivotal role in the judicial policy reforms. The failure of a public authority to respond to a request for information is common in many countries. Denying access to information impacts upon an essential aspect of participatory democracy. When public authorities hold information and do not provide it upon request, they disregard not only the information principle, but also the participation principle. Lack of access to information is a considerable obstacle to effective public participation. Needless to say, the premise is straightforward: the access to understandable rules is conceived as the condicio sine qua non for access to justice [18]. This element entails both a procedural and a substantive side. Indeed, on the one hand, the capacity-building part consists of the creation of instruments (usually related to ICT) in order to improve the actual accessibility of data. On the other hand, rules have been revised, harmonised and categorised in order to be more understandable to stakeholders, especially to nonpractitioners. Under this light, in the last decades several reforms have been carried out both at the national and the supra-national level.

Policies on Access to Justice

The policy reforms on access to justice have been developed according to three key dimensions.

ICTs support to access to justice

The regular reports issued by EU monitor the introduction of systems of external audit (such as statistics, surveys, etc.) and encourage member states to introduce legal databases accessible to the public also thanks to ICTs, which allow citizens to interact directly with the courts.

Since its very beginning, the EU has been equipped with a website comprising an up to date legislation database called Eur-lex (which substituted the previous version, i.e. Celex), which goes far beyond a simple online official journal. Indeed, advanced research tools are available to search for results within a database of 2 815 000 documents (e.g. treaties, legislative acts, preparatory works, case studies etc.) with texts dating back to 1951. It is updated on an annual basis and it is available in the 23 official EU languages [18].

With the deepening of the European integration, also the (procedural) approach to access to justice enlarged its scope. After judicial cooperation in civil matters was included in the European Community aims by the Amsterdam Treaty, ICT technologies have been bolstered by the use of hard law in order to effectively implement them: member states and national courts are legally bound to supply information via the Internet. According to this line, two networks have been established [19]: the European Judicial Training Network (EJTN) and the European Judicial Network (EJN). The former was set up in 2000 by a Belgian law as an informal network of national judicial training agencies with the task of spreading data and exchanging practices through its website. The EJN favours cooperation in criminal matters by pooling together national authorities in charge of international judicial cooperation and by diffusing information through its website

A forward step is the Multi-Annual European e-Justice Action Plan 2009-2013. The Commission started a comprehensive e-reform by issuing the 2008 Communication, urging for a European strategy for e-justice. Such a preparatory work, strongly supported by the European Parliament (EP), gives priority to the operational side of access to justice by emphasizing the prominent role ICT should play: e-justice became the leitmotiv of the Community approach to access to justice. Its primary goal is conceived by the Commission as “to help justice to be administered more effectively throughout Europe, for the benefit of citizens. The first hallmark of priority projects should be that they help legal professionals to work more effectively and citizens to obtain justice more easily. They must also contribute to the implementation of existing European instruments in the field of justice and, potentially, involve all or a large majority of Member States” [20].

Furthermore, international e-justice initiatives may prove to be a relevant platform where practitioners share and spread ideas and ‘good practices’ related to the challenges they face.

The users’ perspective, satisfaction, participation

Contemporary issues concerning access to justice are concerned with the system’s ability to involve users actively in the proceedings.

For users, winning the case is only one of the factors that will influence the image they have of the justice system. If the codes of justice remain a mystery to them and its formality constantly seems strange, if they do not really understand the roles of the various people involved and cannot make an informed assessment of the merits of the actions they undertake, the rights and channels open to them will remain sources of suspicion and uncertainty. Ultimately, the degree of understanding they achieve will enable them to assume their role as actors and handle their contact with the judicial system more effectively, from the earliest stages of access to justice.

Furthermore, the participation of citizens in thinking about the future and role of the justice system is a form of access to justice. Civil society could and should play a role in improving the administration of justice. For this purpose, it could be involved in consultative bodies to which key proposals concerning the functioning of the system would be submitted.

Only a few cases for example provide with the participation of citizens in juries or in committees of evaluation of courts’ performances [11].

The introduction of standards of societal accountability represents a step forward in the direction of a client-oriented judiciary [21]. In order to make a judiciary accountable to civil society it is necessary for the judiciary to be transparent toward the public. Since 2003, when CEPEJ was created, the COE started to monitor the societal accountability according to the following dimensions:

1. Relations with the public and the educational role of the courts in democracy.

2. Relations with all those involved in court proceedings.

3. Accessibility, simplification and clarity of the language used by the court in proceedings and decisions.

So far, the CCJE (2007) defined European standards of societal accountability to be applied to EU judicial systems, such as:

Transparency: front office; systems of e-filing.

- Public communication: websites of judicial institutions; broad and free availability of info about rights of citizens.

- Openess: info about the development of judicial procedures.

- Trust: statistics and surveys available to public.

Alternative dispute resolution mechanism

Massive procedural and substantive reforms of the judicial systems of states have been carried out in the last ten years. Among the former noteworthy reforms is the introduction of alternative dispute resolution (ADR) mechanisms. The extra-judicial or alternative dispute settlement mechanisms include the typical methods falling short of litigation, such as negotiation, mediation, conciliation and arbitration. These mechanisms could provide complainants with the advantages of a swifter and cheaper access to redress.

These out-of-court mechanisms cover schemes that lead to the settling of a dispute through the intervention of a third party, such as an arbitrator, a mediator or an ombudsman. This third party can propose or impose a solution, or, in other cases, can merely bring the parties together and assist them in finding a solution.

As an example, mediation is now more than a distinct process for settling cases and tends to be an adjunct to the traditional judicial system in Europe, working with it interdependently. The emergence of this idea probably indicates a growth in the role of mediation in many member states. From the qualitative point of view, mediation often makes it possible for user needs to be better taken into account, particularly in criminal matters, where it may give victims a voice. It also offers access to a new, less confrontational approach to dispute settlement that strives to calm down tensions after redress has been provided and to foster the reintegration of the offender in criminal cases. From the quantitative point of view, the results are more qualified: civil and family mediation reduce the workload of the judicial system, making judges more available and therefore more accessible to the users [22].

Furthermore, within this field, an active role could be played by equality bodies, NGOs, trade unions and other associations which offer an alternative course of action to that provided by the general courts and often use ADR tools themselves.

In the next paragraph, best or good practices of a more concrete nature related to the above policy streams are sorted out, in order to identify concrete measures to improve both information and access to justice for citizens.

Best or Good Practices on Access to Justice

The european e-justice portal

The European e-Justice portal is one of the most challenging and innovative initiatives recently taken by the European Union to promote the harmonization of rules in several fields, in order to improve access to justice. Officially launched in 2010 within the Multi- Annual European e-Justice Action Plan 2009-2013, the e-justice portal is supposed to be the one-stop-shop website for e-justice in Europe and the main source of information for European citizens on the European justice. It aims at providing judicial support to 22 language speaking stakeholders with its 12000 pages of contents [23].

This is to play a three-fold task. First of all, the portal - as a kind of ‘judicial tourist guide’ for EU citizens in another country - will provide access to relevant information to European citizens regarding: a) victims’ rights and in general citizens’ rights in criminal proceedings; b) guidelines to initiate and manage proceedings in another member state. Secondly, the European e-Justice portal will be at the centre of a network consisting of the already functioning legislation databases, such as Eur-lex. Finally, in the long run such a portal will become an e-justice tool in the proper sense, envisioning not only consultation of data, but also more complex functionalities and services [18].

As far as now, this portal already supplies citizens, judicial practitioners and businesses with helpful and practical information. Not only may citizens deepen their knowledge on other member states’ judicial system, but they are also provided with information on facts related to real-life events, which may occur in another country: how to find a specific practitioner, how to use ADR mechanisms etc. Practitioners have the opportunity to access legislation databases and to create a sort of judicial community using this platform. On their part, businesses are able to consult insolvency and property registers in other member state [23].

Since the beginning of 2011 the European e-Justice Portal made facts about defendants’ rights available: now a citizen is able to know road traffic offences fees in other member state [23]. In the future, it will also be possible to pay fees issued in another member states via an online transfer mechanisms hosted by such a portal.

Furthermore, the e-justice portal is going to include the Judicial Atlas [24], the tool enacted by the European Commission in order to provide a user-friendly access to information relevant for judicial cooperation in civil matters. Atlas aims to help individuals and businesses to identify the competent courts or authorities to which one may apply for certain purposes.

Challenges

The e-justice portal is an access to justice issue in order to support and develop free market within the EU, so technically everyone should be able to use it [25]. However, language, semantic and technical barriers have been experienced during these procedures, from filling out the form to filing it at court. Recent studies [26] have demonstrated that e-services such as the European Payment Order and the Small Claim Procedure need a high level of interoperability among the actors involved in their application. First of all, these procedures entail forms of cooperation at vertical level between national authorities and users and between European institutions and member states. For example member states should provide the European commission with all the relevant information for the practical application of these rules in the national courts in order for the latter to create a common platform of exchange of information, such as the European judicial Atlas in civil matters.

Furthermore, these procedures entail important levels of horizontal interoperability that is mechanisms of cooperation between member states and their national authorities. Interoperability needs for the exchange of information between the national competent authorities (seized courts, judicial functionaries, etc…) concerning international civil cases.

Both vertical and horizontal level of interoperability should work efficiently so as to contribute to the good functioning of the European procedures in civil justice [27]. The construction of a European judiciary space does not only depend on setting common rules but also on the functioning of common mechanisms of interoperability. All the actors involved in the procedure should cooperate and dialogue to avoid the failure of these European procedures, due to their high complexity and their distance from the national users.

The Participative Experiences in Sweden

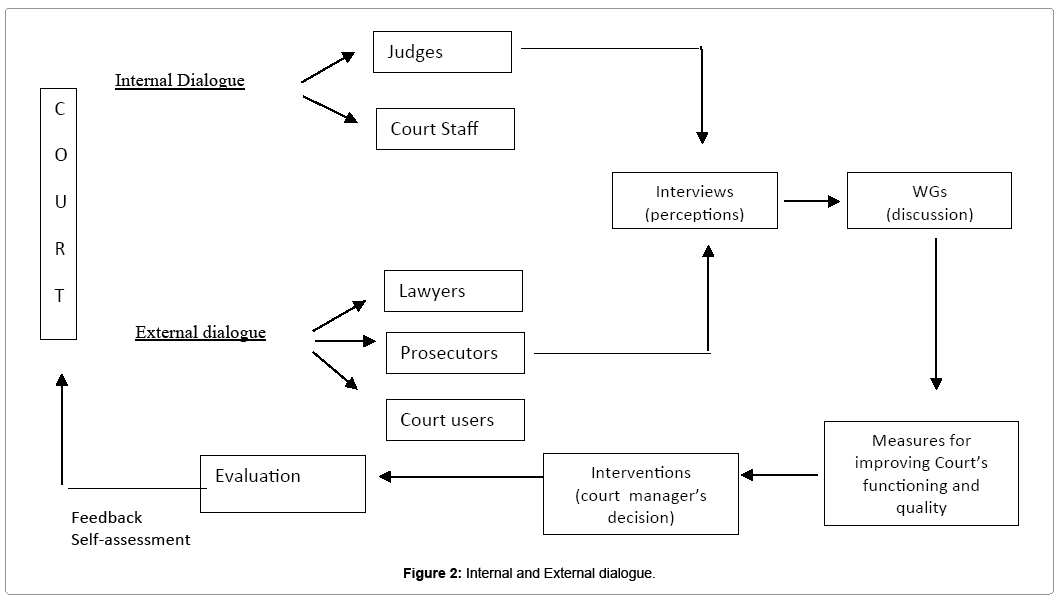

The Sweden case-study refers to a peculiar methodology for Quality Court Management implemented since 2003 in the Swedish courts that had positive effects in terms of citizens’ access to information and access to justice [12]. The projects are based on the use of internal and external dialogue for identifying positive or negative aspects that regard the court’s day-to-day functioning and gather proposals for improving court’s functioning and service. On the one hand, the internal dialogue experience consisted in gathering judges’ and court staff’s opinion on the court’s management and on the policies that can be implemented to improve court’s activities. On the other hand, through the external dialogue, also lawyers, prosecutors, external users as witnesses or defendants have been involved in the process. The elaboration of quality policies has been based on the use of surveys, questionnaires and discussions in small groups. The suggestions gathered during this processes have been discussed by judges and in most of the cases put in practice.

The Method

The method has been used in the Court of Appeal of Western Sweden since 2003 and is now used in six other Swedish courts: Court of Appeal of Skåne and Blekinge, Administrative Court of Appeal of Stockholm, District Court of Hässleholm, District Court of Borås, District Court of Vänersborg and District Court of Göteborg.

On one hand, internal dialogue with all judges and other staff results in a decision by the court manager of what areas that should be chosen for quality work and what measures that should be taken to improve the functioning of the court in these areas. On other hand, external dialogue with lawyers and prosecutors give further suggestions for measures in the areas that the court is already working with as well as suggestions for new areas for the quality work of the court. The external suggestions are discussed internally and decisions are made about further measures and new areas for the quality work of the court. Furthermore, external dialogue with the users of the court (plaintiffs, defendants and witnesses) about the information, treatment and service to the users of the court gives suggestions for measures to improve the functioning of the court in those areas. Moreover, both internal and external dialogue is used as a method for self-assessment and feed-back [28].

The result of the quality work at the Court of Appeal of Western Sweden shows that internal and external dialogue is a good method for quality work in courts. Since the work of improving the handling of civil cases started, the time for handling and passing sentences in civil cases has been cut. The Court of Appeal has now taken the lead among the six courts of appeals in Sweden when it comes to short turnaround time for civil cases (Figure 2) (sentences are passed within 7 months in 75 % of the civil cases) [28].

Finland, Denmark and the Netherlands also have good experiences of the method of a dialogue between judges and interested parties as a tool for improving the functioning of the courts there.

In Finland the Rovaniemi Court of Appeal Jurisdiction and the Court of Appeal meet every year to discuss and decide issues for the quality work of the courts for the following year. After deciding on the themes, judges form working groups with lawyers and prosecutors and sometimes police to work out a proposal for better routines and practices. The proposals are discussed by all judges at the end of the year and then implemented as recommendations for all judges to follow.

In Denmark judges in the Copenhagen area have agreed to work together to improve the written sentences and the treatment of the users during court proceedings. Judges have read each other’s sentences and watched each other’s treatment of the parties and witnesses during court proceedings. They have then entered in a dialogue with each other on how to improve their work.

In the Netherlands systematic quality work is presently managed in all courts of the country. That work was initiated by a several years long period of internal dialogue among judges where the majority of judges eventually agreed on 13 areas where improvements were needed in order to achieve a better functioning of the courts. Within these 13 areas projects were started, where judges took part in suggesting measures to improve the functioning of the Dutch courts [28].

The ADR Mechanisms in the Gender Equality and Antidiscrimination Law

The principle of access to justice is of fundamental importance for victims of discrimination seeking redress. An effective access to justice is a precondition to obtain an effective remedy.

A number of procedural guarantees have been developed by EU legislators and the Court of Justice to ensure effective access to justice in discrimination and gender equality cases. Directives 2000/43/ EC, 2000/78/EC, 2004/113/EC and 2006/54/EC reflect much of the Court of Justice case-law and establish a number of key principles as regards access to justice including provisions on defence of rights, the reversal of the burden of proof and the requirement for an effective, proportionate and dissuasive remedy.

Alleged victims of discrimination may seek redress through the general judicial mechanisms and in accordance with the general national procedural rules. Labour courts or employment tribunals also play an important role in access to justice for victims of discrimination in the field of employment. It is noteworthy that the existence of courts specifically set up to deal with discrimination or fundamental rights cases is extremely rare. To mention, the Equality Tribunal in Ireland which is a specialist body established to deal with discrimination cases and the Spanish law on Integrated Protection Measures against Gender Violence which creates specific courts dealing with violence against women, as well as any related civil causes.

In addition, a number of extra-judicial or alternative dispute settlement mechanisms are available in the EU Member States and in the EFTA/EEA countries. These include the typical methods falling short of litigation, such as negotiation, mediation, conciliation and arbitration, which could provide complainants with the advantages of a swifter and cheaper access to redress. Ombudsmen and equality bodies may also provide an alternative to the general courts. Associations, organisations or other legal entities can also play a significant role in the defence of rights on behalf of or in support of the complainant. Whilst in some countries equality bodies have legal standing and can bring a case to court, in others, they can only provide assistance to the claimant, or provide observations to the court.

Based on a comparative study [29] regarding the 27 EU member States and the EFTA/EEA countries (Iceland, Liechstenstein and Norway) as regards access to justice in cases of discrimination on grounds of gender, race or ethnic origin, religion or belief, disability, age and sexual orientation, examples of alternative dispute resolution mechanisms have been selected as follows:

- In the Czech Republic, independent mediators are available in discrimination cases if agreed to by both parties;

- In Italy, equality advisors, trade unions and associations provide conciliation with an aim to end the discrimination. If conciliation leads to an agreement, the agreement can be enforced;

- The National Office for Conciliation in Luxembourg, formed of representatives of employers‘and trade union organizations as well as representatives of the employers and the employees of the undertakings involved, assesses industrial disputes in the private sector and votes on a decision. If the conciliation process is unsuccessful, the parties can refer the dispute to an arbitration panel.

- Independent mediation centres are available in Slovakia if mediation is agreed to by both parties;

- The Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service are the most well-known alternative dispute resolution provider in the UK. It is involved in conciliation in collective disputes, providing facilities for settling existing or anticipated trade disputes by conciliation. It is also involved in conciliation in individual cases.

Other options are institutions such as the office of the Ombudsman. In some countries, the Ombudsman‘s competence is specifically focused on the protection of fundamental rights; in others, it is a more general entity dedicated to the review of administrative actions. The equality bodies also play a role in assisting victims of discrimination seeking access to justice. Some of the common functions performed by national level bodies such as equality bodies and Ombudsmen are a) providing information on the legal situation; b) receiving, investigating and examining complaints; c) providing advice, assistance and support to victims of discrimination; d) providing conciliation, mediation or negotiation between the parties; e) monitoring the implementation of anti-discrimination legislation [29].

These bodies offer an alternative course of action to that provided by the general courts and often use alternative dispute resolution tools themselves. For example:

- The Federal Ombudsman on Equal Treatment and the Federal Equal Treatment Commission in Austria and the Equal Treatment Commission in the Netherlands provide conciliation and mediation services;

- Equal Opportunities Flanders in Belgium finances contact points whose mission is to find negotiated solutions in cases of discrimination;

- The Estonian Chancellor of Justice and the National Council for Combating Discrimination in Romania mediate disputes between private persons in regard to discrimination on several grounds;

- In Liechtenstein there is a mandatory, free of cost mediation body for discrimination cases whereby an appointed judge advises the parties and settles the dispute.

- The Equality and Human Rights Commission in the UK provides a conciliation service as an alternative route to court action. If a complaint is resolved during the conciliation, it can result in a binding settlement. If it is not resolved, the complainant still has the option of taking the action to court.

In practice, equality bodies can be divided into two basic idealtypes: promotional and quasi-judicial bodies [30]. EU member states have one or the other, or both. Promotion-type equality bodies favor good practices in organizations, raise awareness of rights, develop a knowledge base related to equality and non-discrimination, and provide legal advice and assistance to individual victims of discrimination. Quasi-judicial type equality bodies focus their actions on hearing, investigating and deciding on individual cases of discrimination. Some equality bodies also combine these two models, while some states have both types of bodies.

Let’s See Three Representative Cases for Each Ideal Type

Bulgaria

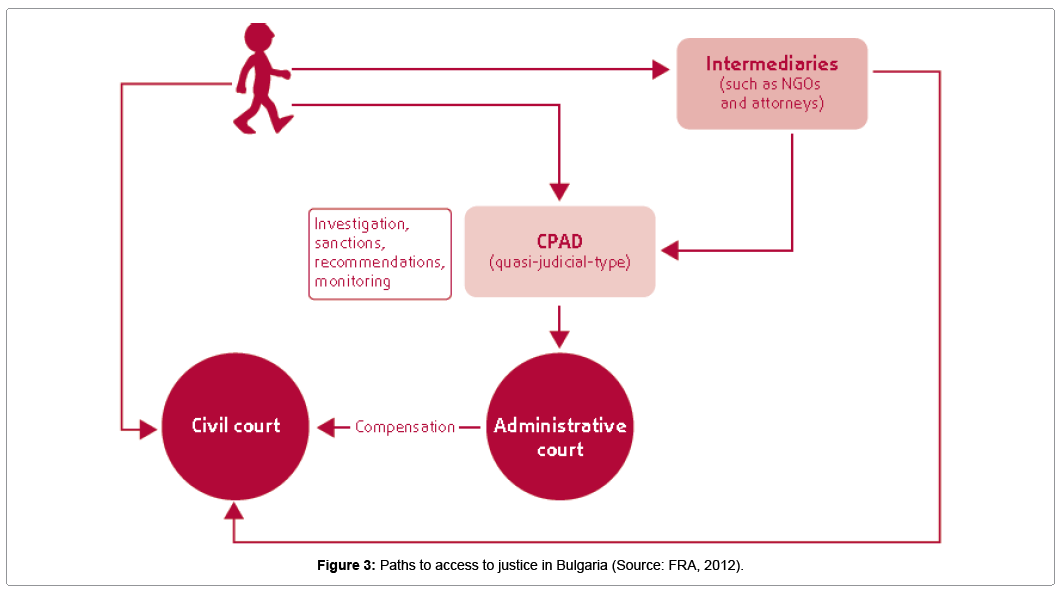

In 2004 Bulgaria released the Protection against Discrimination Act and settled up in 2005 the Commission for Protection against Discrimination (CPAD), a quasi-judicial type equality body. It has the task to hear and investigate complaints from victims of discrimination and to start proceedings on its own initiative. CPAD issues legally binding decisions and mandatory instructions for remedial or preventive redress. It can make recommendations to public authorities, including for legislative change, and can assist victims of discrimination. CPAD may also carry out independent research and publish reports. When a complaint is filed, CPAD initiates proceedings. Admissible cases begin with a fact-finding stage and, after a public hearing, CPAD decides on the merits of the case. CPAD cannot, however, award compensation; courts alone can do this.

Complainants can approach courts (after an administrative court decision, a civil court must be approached) either initially or following a CPAD decision in order to claim compensation. NGOs offer guidance, financial assistance, and other kinds of support to complainants before CPAD and the courts. Some NGOs also act on behalf of complainants or intervene as a third party in proceedings (Figure 3).

Italy

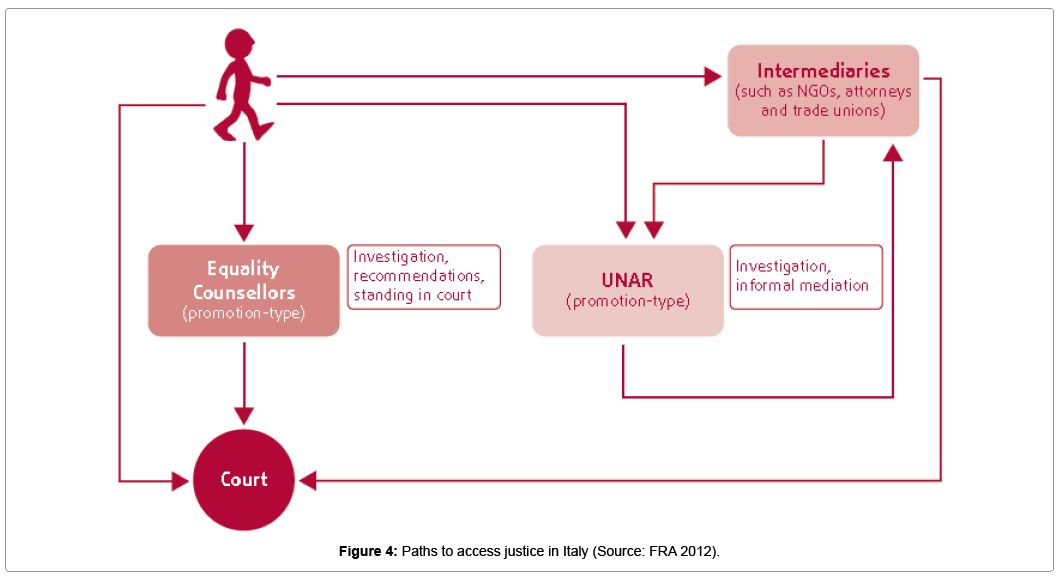

Italy has two main non-discrimination laws, both dating from 2003. Institutional assistance is provided for the grounds of sex and ethnic origin or race. The Minister of Labour in consultation with the Minister for Equal Opportunities appoints Equality Counsellors (Consigliere/i di parità) at provincial, regional and national level with the mandate for issues of equal treatment of men and women in the labour market. The National Office Against Racial Discrimination (Ufficio Nazionale Antidiscriminazione Razziale, UNAR), a promotion-type equality body, was established in 2003. Its task involves the prevention and elimination of discrimination on grounds of race or ethnic origin, the promotion of positive action and the undertaking of studies and research, including awareness-raising activities such as information on discrimination on grounds of age, disability, sexual orientation, ‘transgenderism’, religion and belief. At the level of the provinces and regions, UNAR has established non-discrimination offices and focal points in some locations in cooperation with local authorities and NGOs. These provide first-stage legal advice, counselling and mediation. Equality Counsellors, for the ground of sex, exist at national and regional levels, and are mandated to receive complaints, provide counselling and offer mediation services.

The Equality counsellors cooperate with Labour inspectors (Ispettorati del lavoro) who have investigative powers to establish facts in discrimination cases. The Equality counsellors also have legal standing in court cases with collective impact if no individual victim can be identified. Cases of discrimination on grounds of race or ethnic origin can be referred to UNAR, which initiates investigation procedures and offers informal mediation procedures. UNAR has no legal standing in court, but it can refer victims of discrimination to NGOs and other legal entities listed in a national register of organisations which are entitled to provide legal representation and take action in the general interest of a group (Figure 4).

Regular courts alone can make decisions about the discriminatory content of an action, regulation or other matter, by following the general rules of civil procedures.

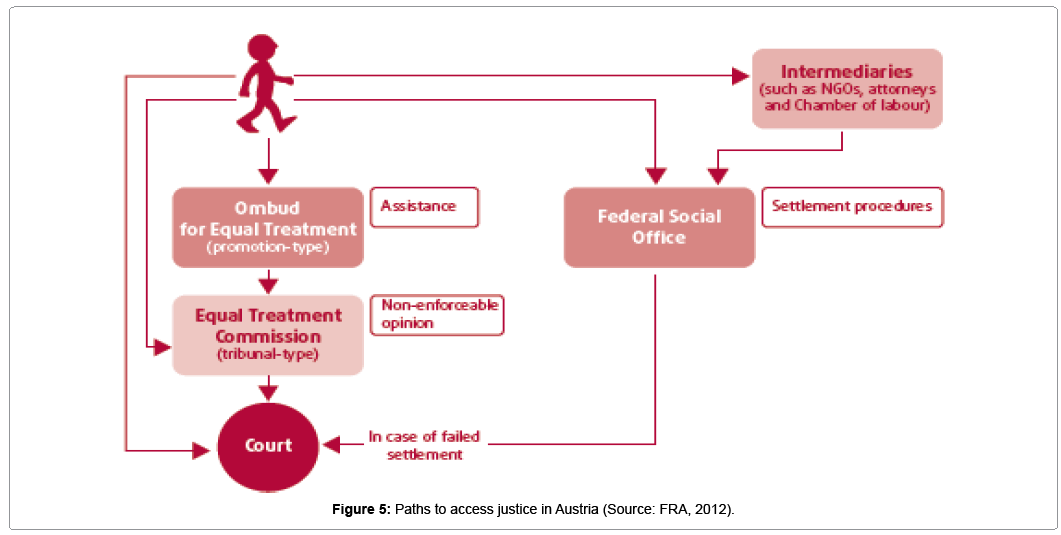

Austria

In Austria, the 2004 Equal Treatment Act ensures the transposition of the EU equality directives. Two equality bodies, the Ombud for Equal Treatment (Gleichbehandlungsanwaltschaft), a promotion-type equality body, and the Equal Treatment Commission (Gleichbehandlungskommission), a quasi-judicial-type equality body, have the mandate to handle issues of equal treatment in the labour market, on the grounds of ethnic origin, religion or belief, sexual orientation or age.

In most instances complainants have two choices. They can bring their case before the Equal Treatment Commission, which can issue a legally non-binding decision on whether or not the treatment in question was discriminatory. Alternatively, they can go to the competent civil, labour or social welfare court and claim damages. Victims of sexual harassment can go directly to criminal court. Complainants can obtain assistance from the Ombud for Equal Treatment, NGOs or, in employment cases, the Chamber of Labour. In cases of discrimination on the ground of disability, the complainant must contact the Federal Social Office (Bundessozialamt) before filing a claim with a court. The Federal Social Office is obliged to initiate a settlement procedure, which must be attempted before a claim can be filed (Figure 5).

The number of bodies and channels through which disputes can be settled shows the complexity of accessing justice for victims of discrimination. Although the existence of specific structures dealing with discrimination is a positive fact that benefits alleged victims, it is crucial that the proliferation of these mechanisms is accompanied by effective dissemination of information about their availability [29].

Conclusions

From our study, three key important factors emerge in order to improve access to justice and, as a consequence, the quality and functioning of the European judicial systems.

a) The ICT as enabler/facilitator: The use of ICTs related to e-justice can play a key role in improving access to justice, especially in the proceedings concerning cross border judicial disputes. The e-justice portal could provide European citizens with the tools to solve the increasing number of cross border disputes. Technology is a tool that, if rightly used, can enhance and support democratic processes. E-justice is an opportunity, enabler and facilitator for increased citizens participation, improved functioning and quality of European judicial systems. It is about offering access to more information, closely linked to the concepts of transparency and accountability, and of good governance. However, there are no ‘one size fits all tools available’. Citizens/users need to be trained to the ICTs use and instructions should be comprehensive as much as possible, by avoiding language barriers. It means that the e-justice platform needs to be made interoperable on a technological, organizational and institutional dimension. The challenge is to develop systems that balance between procedural simplicity and minimal complexity requirements compatible with functionality and legal fairness, and at the same time capable of evolving and adapting to changing circumstances.

b) The judicial actors involvement: The focus on the Swedish participative experience is interesting because refers to techniques of citizens’ involvement on the decisions affecting their courts.

The method of an internal and external dialogue has shown to be a critical factor in improving the quality and functioning of courts, especially related to the access to justice. By involving court’s staff and users (lawyers, citizens, etc.) in a broad dialogue of what needs to be improved – a bottom-up approach - leads to greater improvements in the functioning of an organisation than a traditional top-down approach.

The techniques implemented by some Swedish courts can be considered a version of ‘deliberative forums’ applied to justice. The citizens’ and external users’ involvement and the tools that favour dialogue (for instance the fact that heads of court do not actively participate in focus groups where court staff or external users are involved in order to foster participation to discussion), are typical characteristics of deliberative projects implemented in several other contexts. This has a twofold implication on the access to justice issue. On the one hand, deliberation and participation procedures are accompanied by cognitive processes; the deliberation brings about an exchange of information between participants (in this case, external users and court staff). On the other hand, citizens empowerment in the decisions regarding their court, give them the opportunity to propose policies for both access to justice and judicial systems functioning improvement.

c) The key role of equality bodies and administrative/judicial institutions: ADR mechanisms enhance access to justice, providing a cheap and expeditious alternative to court dispute resolutions. ADR schemes aim to settle disputes in an amicable way, and are more flexible than ordinary court procedures.

The ADR case in the gender equality and anti-discrimination law shows a wide range of different approaches, including arbitration, ombudsmen, mediation and conciliation schemes. All EU Member States have transposed the EU equal treatment directives into national law and designated a body or bodies to ensure access to justice in discrimination cases. Given the institutional autonomy of the Member States within the EU, the directives do not prescribe a specific structure. There are consequently many differences in the structures established. The justice systems in discrimination cases in EU Member States can be characterised by three different types: quasi-judicial-type equality bodies and courts, promotion-type equality bodies and courts and hybrid systems with both promotion-type and quasi-judicial-type equality bodies and courts. Even within these three categories, equality bodies play a range of roles and offer a variety of paths to access justice. The paths available depend on the national context as well as on the type of case and ground of discrimination.

Furthermore, the impact of the decisions adopted by ADR schemes also differ: some are merely non-binding opinions, whereas others are binding on the parties, if the complainants accept the final decision taken by the equality body.

Last, but not least, a recurring issue raised by the EU level associations is that whilst there is progress in terms of awareness and promotion of fundamental rights, this is not matched by an equivalent level of awareness of, and accessibility to, remedies for these rights. Often, victims of discrimination are not aware of the legal remedies available and do not know how to access courts or alternative mechanisms for defending their rights.

Nevertheless, equality bodies and administrative/judicial institutions play an important role in improving access to justice, with promotion-type bodies facilitating access to the courts or other institutions that hear cases and with quasi-judicial-type bodies hearing cases themselves in less formal procedures. Equality bodies may also process or assist in a number of cases.

References

- Page EC, Wright V (1999) (eds), Bureaucratic Élites in Western European States, Oxford, Oxford University Press, USA.

- Page EC, Wright V (2007) (eds), From the Active to the Enabling State: the Changing Role of Top Officials in European Nations, Palgrave, Macmillan.

- Peters BG, Pierre J (2001) Politicians, Bureaucrats and Administrative Reform, London, Routledge, UK.

- Pollit C, Bouckaert G (2004) Public Management Reform, Oxford Press, Oxford, New York, USA.

- Carboni N (2010) Professional Autonomy vs. Political Control: how to deal with the dilemma. Some evidence from the Italian core executive. Public Policy and Administration 25: 1-22.

- Carnevali D, Contini F (2010) the quality of justice: from conflicts to politics, in Coman, R. and C. Dallara (eds), Handbook of Judicial Politics, European Institute Editions, Iasi.

- Carboni N (2012) Il New Public Management nel settore giudiziario.

- Carboni N, Velicogna M (2012) Electronic Data Exchange within European Justice: e-CODEX Challenges, Threats and Opportunities. International Journal For Court Administration: 1-17.

- Antonio C, Carla BM (2012) A public value perspective for ICT enabled public sector reforms: a theoretical reflection. Government information quarterly 29: 512-520.

- Antonio C, Leslie W (2012) Government policy, public value and IT outsourcing: the strategic case of ASPIRE. The journal of strategic information systems.

- Contini F, Mohr R (2007) Reconciling Independence and Accountability in Judicial Systems. Utrecht Law Review 3: 26-43.

- Contini F (2010) The reflective court: dialogue as key for “quality work” in the Swedish judiciary. In Quality management in courts, ed. P Langbroek. Strasbourg: CEPEJ.

- Fung A (2003) Deepening Democracy: Institutional Innovations in Empowered Participatory Governance . London, UK.

- Carson L, Hartz-Karp J (2005) Adapting and Combining Deliberative Designs: Juries, Polls, and Forums. J Gastil and P Levine (a cura di): 120-138.

- UNDP (2004), Access to Justice: Practice Note.

- Velicogna M (2011) Electronic Access to Justice: From Theory to Practice and Back. Droit et Cultures 61: 71-117.

- CCJE (2007) Opinion n. 10, Strasbourg 2007.

- Vannoni, M. (2011), Access to data as the condicio sine qua non of access to justice: the European e-Justice Strategy, Effectius Newsletter, Issue 15, (2011).

- Storskrubb (2008) Civil Procedure and EU Law A Policy Area Uncovered, Oxford: Oxford University Press, New York, USA.

- CEC (2008) Proposal for regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council regarding public access to European Parliament, Council and Commission documents, Commission of the European Communities, CEC.

- Piana D (2010) Judicial accountabilities in new Europe: from rule of law to quality of justice, Farnham, UK.

- CEPEJ (2010) Access to justice in Europe.

- EUROPA Press Release, 2010. European e-Justice internet portal offers quick answers to citizens’ legal questions.

- COE (2012) Implementation of the European e-Justice action plan - State of play of the revised roadmap, Council of the European Union.

- Ng G (2013) Experimenting with European Payment Order and of European Small Claims Procedure, in Contini, F. and G. Lanzara (2013), Building Interoperability for European Civil Procedings online, CLUEB Bologna.

- Contini F, Lanzara G (2013) Building Interoperability for European Civil Procedings online, CLUEB Bologna.

- Mellone M (2013) Legal Interoperabilit: the case of European Payment Order and of European Small Claims Procedure, in Contini, F. and G. Lanzara (2013), Building Interoperability for European Civil Procedings online, CLUEB Bologna.

- Hasgard MB (2012) Internal and External dialogue: a method for quality management in courts.

- Milieu LTD (2011) Comparative study on access to justice in gender equality and anti-discrimination law.

- European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) (2012)Access to justice in cases of discrimination in the EU. Steps to further equality, Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Relevant Topics

- Civil and Political Rights

- Common Law and Equity

- Conflict of Laws

- Constitutional Rights

- Corporate Law

- Criminal Law

- Cyber Law

- Human Rights Law

- Intellectual Property Law

- International public law

- Judicial Activism

- Jurisprudence

- Justice Studies

- Law

- Law and the Humanities

- Legal Philosophy

- Legal Rights

- Social and Cultural Rights

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 16075

- [From(publication date):

November-2014 - Aug 19, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 11356

- PDF downloads : 4719