Research Article Open Access

Late Entry into Antenatal Care in a Southern Rural Area of Vietnam and Related Factors

Ngo Thi-Thuy-Dung1,4*, Nguyen Ha-Duc2, Truong Quang-Dinh2, Nguyen The-Dung1, Philippe Goyens3 and Annie Robert41Pham Ngoc Thach University of Medicine, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

2Pediatric Hospital Number 2, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

3Université Libre de Bruxelles, Nutrition and Métabolisme Unit and Laboratory of Pediatrics, Brussels, Belgium

4Université Catholique de Louvain, Institute of Experimental and Clinical Research, Center for Epidemiology and Biostatistics and Public Health School, Brussels, Belgium

- Corresponding Author:

- Ngo Thi-Thuy-Dung

Pham Ngoc Thach University of Medicine

Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

Tel: 84937157967

E-mail: dungngo.yhcd@gmail.com

Received date: May 22, 2017; Accepted date: June 05, 2017; Published date: June 10, 2017

Citation: Thi-Thuy-Dung N, Ha-Duc N, Quang-Dinh T, The-Dung N, Goyens P, et al. (2017) Late Entry into Antenatal Care in a Southern Rural Area of Vietnam and Related Factors. J Preg Child Health 4: 334. doi:10.4172/2376-127X.1000334

Copyright: © 2017 Thi-Thuy-Dung N, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Pregnancy and Child Health

Abstract

Aim: The aim of this study were to assess the proportion of pregnant women who attended ANC late in pregnancy and to identify factors associated with late entry in communities in South Vietnam. Background: Antenatal care (ANC) in Vietnam remains a problem suboptimal in Vietnam and there is limited information of on late entry into ANC. A study conducted in 2008 in the North of Vietnam showed 2.8% of late entry into ANC in 2.8% of women in an urban area, against versus 30.9% of women in a rural area. The aims of the present study were to assess the proportion of pregnant women attending ANC late in their pregnancy and to identify factors associated with late entry in ANC in rural communities of South Vietnam in 2014. Methods: This community-based study enrolled 1,448 pregnant women who were identified by 72 village health workers in 17 communities. First initiation to ANC after first trimester of pregnancy was considered as a late entry. Related factors were selected and analysed based on the Andersen Health Seeking Behaviour model. Multivariate logistic regression was used to identify independent factors associated with late ANC. Results: The prevalence of late ANC attendance was 8.2%. Having a poverty certificate (26.9%), having a history of abortion (19.4%), living in an ethnic minority community (17.2%) and being a teenager (15.5%) were the factors associated with late entry into ANC for pregnant women. Conclusion: The proportion of pregnant women entering late into ANC in rural Southern Vietnam remains higher than in urban areas (8.2% vs. 2.8%). Health education on the importance of attending ANC early should focus on poor people, on women who have an abortion history, on ethnic minorities, and on teenagers to promote significant early entry into antenatal care, thus improving maternal and child health.

Keywords

Antenatal carep; Late entry; Southern of Vietnam; Health seeking behaviour

Abbreviations

ANC: Antenatal Care; CHS: Commune Health Station

Background

Despite progress and efforts made to reverse the trend, maternal and neonatal mortality and morbidity remain an urgent concern in lowincome countries. Globally, there were an estimated 289,000 maternal deaths in 2013 and the maternal mortality ratio in developing regions was 14 times higher than in developed regions [1]. The proportion of neonatal deaths among under-five year old deaths is rising in every region. In the developing regions, 2.6 million new-borns died within 28 days of birth, accounting for 45% of global under-five deaths in 2015 [2]. Most of these maternal deaths, neonatal deaths, and stillbirths have been proven preventable [3-5].

Research has indicated that antenatal care (ANC) effectively improves pregnancy outcomes through detection and management of pregnancy-related complications [6]. Although ANC in high-income countries has been applied for a long time and has made remarkable achievements, most ANC programs established in low and middleincome countries in Africa and Asia are largely underutilized [6]; the low number of women attending ANC late is still a major concern [7].

Early entry into ANC is an important recommendation for all pregnant women. Determining patients’ medical and obstetric history and certain baseline measurements should be done at an early visit. Such visits enable early identification of women requiring special care [8] and allow for on-time treatment of complications or risk factors that affect the fetus, if possible [9]. Initiation of antenatal care in the first trimester allows for early commencement of health education and counselling on appropriate diet and exercise, for help resisting smoking and alcohol consumption during pregnancy, for preventing certain complications of pregnancy, labor and puerperium, and for further discussions about antenatal screening [8-10]. The optimum time for most screening tests, such as Trisomy 21 (Down’s syndrome), HIV, syphilis and other infectious diseases, is prior to 14 weeks of gestation [11,12], in order to implement appropriate intervention early enough to prevent pathology. Moreover, all pregnant women should be offered an ultrasound scan within the first trimester for accurate assessment of gestational age [13].

However, ANC in Vietnam remains a suboptimal. Although the proportion of women who had at least one ANC visit increased from 71% in 1997 [14] to 93% in 2012 [15], the infant mortality rate dropped only slightly from 17.8 to 15.4 per 1,000 live births. In addition, the maternal mortality ratio has only slowly decreased in recent years [16]. Among maternal deaths, 65% of the mothers did not use any ANC, 22% received one ANC visit, and only 13% received two or more.

Although information regarding reproductive health for Vietnamese women is frequently addressed in routine statistics at the national level, the number of pregnant women starting ANC within first trimester is not frequently reported. In addition, despite some studies with published data on ANC, there is limited information focusing on late entry into ANC.

Studies have shown that factors related to late entry into ANC are age, ethnicity, education, employment status, place of residence, economic status, health insurance, travel time to the ANC center, and parity [17-19]. A widely-used model in numerous studies exploring the usage of health care services is the Andersen Health Seeking Behavior model [20]; it has also been particularly used in several studies on ANC [17,21,22]. Nonetheless, there is limited information on the factors related to late entry into ANC in Vietnam and a theoretical health seeking behavior model as a framework for the analysis of these related factors has not yet been published.

Methods and Materials

Study design and participants

The present study was carried out in the communities of the district of Trang Bom, from June 2014 to November 2014. It was an observational study of ANC utilization and its determinants. It was conducted to gather information at the grassroots level of the health care system.

Trang Bom is a rural area with a population density of 753.5 inhabitants per km2. Although it is a rural district, Trang Bom is located in the province of Dong Nai, which is an industrial and manufacturing area in Vietnam with an advanced roadway system. People living in Trang Bom are able to reach Ho Chi Minh City, which is 50 km south-west, by taking the National Highway. The district of Trang Bom is located on the National Highway 1, at about 50 km northeast of Ho Chi Minh City 1. Trang Bom benefits from the socioeconomic development and healthcare system support of Ho Chi Minh City. The proportion of working-age individuals in the population of Trang Bom is 72%. As part of the whole province of Dong Nai, Trang Bom is a “'new-style rural” area with a median annual income around 1,700 USD/capita, with a large variability.

The socialist government organizes the public healthcare system in Vietnam, including in Trang Bom. Trang Bom has an organizational health care structure of 17 Commune Health Stations (CHS) at the primary health care level. The proportion of CHS reaching national criteria for CHS in Trang Bom is 100%. Some obstetric and mother and maternal and child health care are provided at all CHS [23], but there is less than one physician per CHS, so most antenatal care services are supervised by midwives. Private facilities are also part of the Vietnamese healthcare system. After their working hours in a public health facility, health workers usually work in private facilities, making a very dense network of healthcare facilities, with an average distance to access the nearest facilities for ANC that is less than 2 km.

During the study period, 72 village health workers in 17 communities consecutively identified 1,448 pregnant women by communicating with households in villages.

Assessment of late entry into ANC and data collection

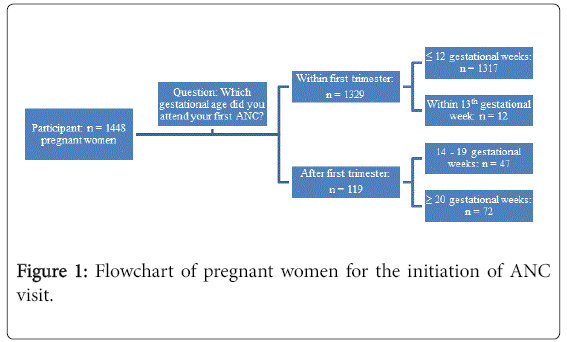

At the first contact with a pregnant woman, the village health worker opened a file for her and recorded her gestational weeks of pregnancy. If a woman was at or less than 13 gestational weeks at the time of detection, the village health workers gave the woman an invitation to go to CHS as soon as possible for ANC visit. The village health worker then came back after 34th gestational week to invite the woman to participate in the research. If a woman was at or greater than 13 gestational weeks at the time of detection, she was invited to participate in the research and was interviewed as soon as possible. In our study, the data regarding the first trimester and the ANC visit were collected at the 14th gestational week or later. A pregnant woman who had never attended ANC was classified as a late ANC attender, according to the Vietnam National Guidelines. The pattern of initiation of an ANC visit according to trimester among pregnant women in this study is described in Figure 1.

To determine the gestational age, the village health workers used the first day of the last normal menstrual period to calculate the weeks of amenorrhea for pregnant mothers who were sure of this date. Confirmation that they were not using contraceptives and that their menses were regular prior to conception was obtained. If pregnant woman who was not sure of the date, the result of the first obstetric ultrasound scan was used to determine gestational age. It should be noted that in Vietnam, when a pregnant woman attends ANC at a health facility, she always receives a booklet or paper with the results of the examination at that time and an appointment for a next ANC visit. In our study, we also verified ANC attendance by checking the ANC booklet, if already opened.

Trained village health workers interviewed the pregnant women using a pre-test questionnaire to obtain information about various factors based on the Andersen Health Seeking Behavior model and information related to their ANC utilization.

Variables based on Andersen health seeking behavior model

To study factors influencing late entry into ANC, we used a number of explanatory variables based on the Andersen Health Seeking Behavior model. This model [24,25] is a multilevel model that incorporates characteristics of individuals, populations, and the surrounding environment as the determinants of health services utilization. When factors other than needs are the dominant driving factors behind health care utilization, then inequality exists. The framework specifies several main components: predisposing characteristics, enabling resources, needs, and personal health care behavior. These characteristics are outline in more detail below.

Predisposing characteristics

Predisposing characteristics are often related to socio-cultural characteristics of individuals existing prior to the illness. These include demographic characteristics, such as age of pregnant women and marital status, and social structure, such as ethnicity, education, and occupation.

Enabling resources

These factors refer to the financial availability of services, which directly impacts the utilization of health services. A poverty certificate and health insurance were considered as enabling factors in this study. A poverty certificate is an official proof given to household or person whose income is lower than 650,000 VND/month (around 30 USD) in a rural area and lower than 850,000 VND/month (around 39 USD) in an urban area, between 2011 and 2015. People who own a poverty certificate have the right to free health insurance and education. In our study, health insurance status was classified into three categories: mandatory insurance, optional insurance, and no health insurance. Having health insurance allows people to utilize health care services free of charge at the primary health care level. In addition, they are reimbursed a part of health care costs when using services at other public levels of the healthcare structure.

Needs

Certain information on obstetric history was considered as a need factor. Relevant information included the number of previous pregnancies, the number of previous abortions, and the number of previous miscarriages, the number of live births and the type of last delivery.

Statistical analysis

Data are reported as mean and standard deviation for continuous variables and as number and proportion for discrete variables. Associations between variables and late entry into ANC were assessed using odds ratio with 95% confidence interval and a chi-square test was used for statistical significance. All tests were two-tailed and a pvalue <0.05 was considered as significant. All variables with a univariate p value <0.05 were entered into a multiple logistic regression model to test for independent associations. In univariate analysis, if a significant variable had more than 2 levels, prevalence was compared between levels. The levels having similar prevalence were pooled to have binary variables. Multivariate logistic regression was then performed in order to emphasize on the independent factors associated with late ANC. Variables with a non-significant contribution to association in the logistic regression model were removed in the building of a final model.

Statistical software

All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS 22.0 statistical software.

Ethical considerations

The Ethical Committee of the Université catholique de Louvain in Belgium approved the present study. The CHS of the district of Trang Bom worked in cooperation with a “health structures” network between Ho Chi Minh City and the province of Dong Nai. The researcher obtained all the necessary permission from the university and the authorities of the district of Trang Bom, in collaboration with the Belgium government. The participants were informed about the purpose of the project and their right to decline participation. A written consent was obtained from all pregnant women.

Results

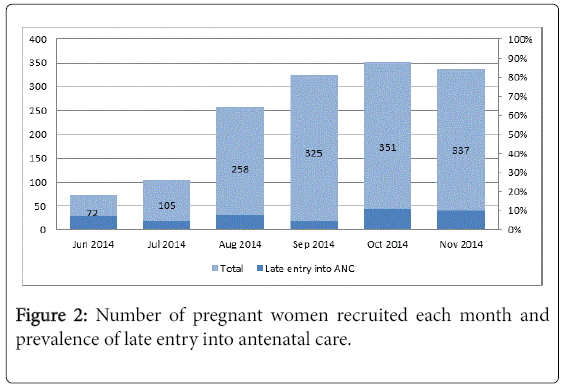

Between June 2014 and November 2014, a total of 1,448 pregnant women were enrolled in the study. The number of women recruited each month is displayed in Figure 2.

None of the pregnant women refused to participate in the study. In June and July, at the beginning of the study, few pregnant women were recruited. The total number of late ANC attenders was 119. In the group of pregnant women initiating ANC visit within first trimester, a majority attended a medical doctors' private consulting office for their first visit (64.6%, 858/1329), while the attendance at the CHS and the District Hospital of Trang Bom accounted for 1.4% and 16.4%, respectively. All distances between a pregnant women’s house and the nearest facility were less than 5 km. Of the 1,448 pregnant women, single pregnant women/mothers accounted for a small proportion (0.4%). The proportion of pregnant women practicing Catholicism/ Protestant, ancestor worship, and Buddhism was 42.5%, 36.7% and 20.8%, respectively. While almost all pregnant women were nonsmokers, 72% were living with a smoker. Only 1.7% of the pregnant women reported drinking any alcohol in the first trimester.

Predisposing characteristics and enabling resources of pregnant women

The socio-demographic characteristics of the 1,448 pregnant women are presented in Table 1. The average age of women was 26.9 ± 9.8 years, 5% were teenagers. The proportion of pregnant women living in an ethnic minority community was 4.4%. About half of the pregnant women had attended secondary school (for which graduation typically occurs at 15 years old) or lower (49.4%) and 48.8% were working in the private sector (48.8%, 706/1448). Nearly one third of pregnant women had no health insurance and the proportion of women who had a poverty certificate was 1.8%.

| n | Late entry into ANC visit | OR (95% CI) # | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All pregnancies predisposing characteristics | 1448 | 119 (8.2%)* | |||

| Age of pregnant women | 0.03 | ||||

| <20 years | 71 | 11 (15.5) | 2.36 (1.07-4.79) | ||

| 20-29 years | 972 | 70 (7.2) | 1 | ||

| ≥ 30 years | 405 | 38 (9.4) | 1.41 (0.90-2.16) | ||

| Ethnic group | 0.02 | ||||

| Minority | 64 | 11 (17.2) | 2.45 (1.24-4.83) | ||

| Kinh or Chinese | 1384 | 108 (7.8) | 1 | ||

| Education group | 0.03 | ||||

| Lower or Secondary | 716 | 70 (9.8) | 1.51 (1.03-2.21) | ||

| High school or upper | 732 | 49 (6.7) | 1 | ||

| Occupation | 0.03 | ||||

| Public worker | 136 | 20 (14.7) | 2.26 (1.23-4.03) | ||

| Private worker | 706 | 50 (7.1) | 1 | ||

| Independent | 281 | 22 (7.8) | 1.11 (0.63-1.92) | ||

| Home worker | 325 | 27 (8.3) | 1.19 (0.70-1.98) | ||

| Enabling resources | |||||

| Poverty certificate | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 26 | 7 (26.9) | 4.31 (1.49-10.97) | ||

| No | 1422 | 112 (7.9) | 1 | ||

| Health insurance | 0.84 | ||||

| No | 428 | 35 (8.2) | 1.06 (0.64-1.75) | ||

| Mandatory | 503 | 44 (8.7) | 1.14 (0.71-1.84) | ||

| Optional | 517 | 40 (7.7) | 1 | ||

Table 1: Univariate association between late entry into antenatal care and socio-demographics of pregnant women (*: Data are number and row percentage; #: Outcome was either entry into ANC early (within first trimester) or late (after first trimester).

Obstetric history and health behaviour characteristics of pregnant women

Table 2 shows obstetric characteristics and behavior characteristics of women who participated in the study. Less than half of women (47.8%) were primiparous. In comparison, 55% (769 women) had at least one previous pregnancy. Of them, the proportion of women reporting a history of abortion or miscarriage was low (54.5% and 13.4%, respectively). About half of women had at least 1 child before (52.2%), while 11.1% had 2 children, 1.7% had 3 and 0.8% had 4 or more. Out of the 769 women with a previous delivery, 18.4% had a caesarean at the last delivery.

| N | Late entry into ANC visit | OR (95% CI) # | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All pregnancies | 1448 | 119 (8.2%) * | |||

| No. of previous pregnancies | 0.42 | ||||

| 0 | 652 | 50 (7.7) | 1 | ||

| 1 | 532 | 42 (7.9) | 1.03 (0.66-1.62) | ||

| ≥ 2 | 264 | 27 (10.2) | 1.37 (0.81-2.30) | ||

| History of abortion | 0.02 | ||||

| No | 760 | 62 (8.2) | 1 | ||

| Yes | 36 | 7 (19.4) | 2.72 (1.14-6.46) | ||

| (First pregnancy) | 652 | - | |||

| History of miscarriage | 0.23 | ||||

| No | 689 | 63 (9.1) | 1 | ||

| Yes | 107 | 6 (5.6) | 0.59 (0.25-1.40) | ||

| (First pregnancy) | 652 | - | |||

| No. of live birth | 0.048 | ||||

| 0 | 692 | 54 (7.8) | 1 | ||

| 1 child | 558 | 40 (7.2) | 0.91 (0.58-1.42) | ||

| ≥ 2 children | 198 | 25 (12.6) | 1.71 (1.00-2.88) | ||

| Last delivery | 0.04 | ||||

| Vaginal | 620 | 60 (9.7) | 1 | ||

| Caesarean | 140 | 6 (4.3) | 0.42 (0.14-0.99) | ||

| (No previous delivery) | 688 | - | |||

Table 2: Univariate association between late entry into antenatal care and obstetrical characteristics of pregnant women (*: Data are number and row percentage; #: Outcome was either entry into ANC early (within first trimester) or late (after first trimester).

Late entry into ANC

Overall, the prevalence of late ANC attendance was 8.2%. The gestational age at first ANC visit was 7.1 ± 1.9 weeks in the group of early attenders. In late attenders, it was 21.2 ± 4.3 weeks. Overall, the median gestation at first visit was 7 weeks, ranging from 5 weeks to 38.5 weeks. In a univariate analysis, the proportion of pregnant women aged less than 20 years who entered late into ANC was 15.5%, whereas there were no cases of women aged over 40 years who entered late into ANC. The other factors significantly associated with late entry into ANC were being from an ethnic minority (17.2%), women having lower or secondary education (9.8%), being a public worker (14.7%), and women with a poverty certificate (26.9%). Pregnant women who had a history of abortion were also more likely to enter late into ANC than others. Pregnant women who previously had a caesarean and women who had less than 2 children, on the other hand, were less likely to enter late into ANC (Table 3).

| Late entry into ANC (%) @ | OR (95% CI) * | p-value* | OR (95% CI) # | p-value # | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <20 years | 0.03 | 0.02 | ||||

| Yes | 15.5 | 2.18 (1.06-4.48) | 2.18 (1.1-4.27) | |||

| No | 7.8 | |||||

| Ethnic group | 0.02 | 0.01 | ||||

| Minority | 17.2 | 2.27 (1.12-4.57) | 2.38 (1.19-4.76) | |||

| Kinh or Chinese | 7.8 | |||||

| Education group | 0.18 | |||||

| Lower or Secondary | 9.8 | 1.31 (0.88-1.96) | ||||

| High school or upper | 6.7 | |||||

| Occupation | 0.72 | |||||

| Public worker | 14.7 | 1.15 (0.53-2.48) | ||||

| Others | 7.5 | |||||

| Poverty certificate | 0.006 | 0.005 | ||||

| Yes | 26.9 | 3.63 (1.47-9.16) | 3.69 (1.47-9.22) | |||

| No | 7.9 | |||||

| History of abortion | 0.03 | 0.01 | ||||

| At least 1 time | 19.4 | 2.63 (1.10-6.29) | 2.93 (1.245-6.91) | |||

| None | 7.9 | |||||

| No of livebirths | 0.14 | |||||

| >=2 children | 12.6 | 1.49 (0.88-2.53) | ||||

| <=1 child | 7.5 | |||||

| Type of last delivery | 0.2 | |||||

| Vaginal | 9.7 | 1.31 (0.86-2.02) | ||||

| Caesarean | 7.1 | |||||

Table 3: Factors associated with late entry into antenatal care using multiple logistic regression model (@: Proportion with this characteristic entering ANC after first trimester; *: Model with 8 variables; #: Model with 4 variables).

Multiple logistic regression model

Using a logistic regression model, factors independently associated with late entry into ANC were as follows: having a poverty certificate, having a history of abortion, living in an ethnic minority community, and being a teenager.

Discussion

This study aimed to estimate the prevalence of late entry into ANC in a rural district of Vietnam in 2014 and to identify related factors.

The number of pregnant women recruited by village health workers was lowest in the first month. Village health workers are members of a village and play an important role in primary health care. Some of them are volunteers, and others are chosen by community members or organizations to connect with villagers. At the beginning of data collection, the village health workers were not previously trained for the task of detecting and interviewing pregnant women. The first two months of the study (June and July) therefore served as a pilot period. The number of cases detected during these months was lower than in the remaining four months due to this accommodation period. However, data from June and July were analyzed once separately and once together with the other cases. The results showed similar proportions, so all pregnant women recruited over the six months were included in the reported results.

Using the official statistics reporting the yearly average number of new-borns in Trang Bom in 2012, the detection rate of pregnant women in our study was estimated around 81.7%. Some pregnant women were immigrant workers who tend to go back to their hometown during pregnancy and for delivery. It is therefore likely that some pregnant women were not identified. However, all the pregnant women detected by village health workers accepted to participate in our study. Such a high participation rate can be explained by different reasons. A Vietnamese pregnant woman usually shows a cooperative attitude, according to Vietnamese Socialist policies, and in line with maternal health campaigns. The campaigns were conducted encourage pregnant women to go to a CHS for check-ups or tetanus vaccination. Another reason is that a pregnant woman is often considered as the guilty party if any problem happens during her pregnancy, especially if she did not attend ANC visit. Social pressure affecting the attendance of ANC can also therefore come from the gender-powered relationship with husbands and family-in-law. In addition, in this study, the village health workers were paid per reported case of participated pregnant woman.

The proportion of women who entered late into ANC in our study was 8.2%. In a study published in 2012, authors reported a proportion of late ANC attenders in 30.9% of women in FilaBavi, a rural health and demographic surveillance site of Hanoi, in the north of Vietnam. The proportion was 2.8% in an urban site of Hanoi [26]. Such a higher value in the North compared to our study, which was also conducted in a rural area, can be explained by different reasons. Firstly, access to CHS can be more difficult in the North than in the South. Northern rural areas are mountainous and transportation can be slow and time consuming, while the district of Trang Bom in our study is a Southeast midland plain. It is located in a convenient position with a quite rapid access to CHS or to upper-level health care facilities within the Province of Dong Nai, as well as with good access to maternities of Ho Chi Minh City. A second reason might be the improvement in Vietnamese healthcare system over the years. That is, the study in FilaBavi was conducted in 2008, when the percentage of CHS having midwives or obstetric assistants was 77.5% in Hanoi, while our study was conducted in 2014, when this percentage was 100% in Trang Bom [23]. A third reason can be a higher proportion of poor people in FilaBavi than in Trang Bom, because both studies showed that living in poor communities was associated with a late attendance in ANC. In the present study, 26.9% of women with a poverty certificate entered late in ANC, not far from the 36.2% reported in FilaBavi. Young age and living in an ethnic minority community were also two independent determinants of late entry in ANC in both studies, even though the definitions were slightly different. That is, a young age for a pregnant woman was <25 years in FilaBavi and it was <20 years in Trang Bom. Nonetheless, in line with the study conducted in FilaBavi in the North, our study highlights the need for targeting minorities, poor people, and young girls when setting up information campaigns for promoting early entry into ANC in Vietnam.

The proportion of late attendance in ANC in our study is also lower than that reported in other low or middle income countries such as Indonesia (21.4%, 2007) and Jordan (9.7%, 2007) [27]. Several reasons might explain such low value. As mentioned above, the easy access to health facilities based on the convenient position of the district of Trang Bom might be the first reason. Secondly, the high density of the healthcare network, including public and private facilities, in Trang Bom can also contribute to a high proportion of women starting ANC within first trimester. Of note, although the overall proportion of late attenders was relatively low in our study, this proportion was quite high among poor pregnant women (26.9%), making this group a target for promoting early entry into ANC.

The median gestational age at first visit in our study was smaller than that reported in some other countries such as Australia (40.6% late attenders and a median gestation of 12 weeks at first visit) [17]. Compared to our study, a research conducted in Belgium showed a similar proportion of late entry into ANC and a similar median gestational age (10.8% of late attenders, 7 weeks of gestation) [28].

In our study, variables independently associated with late entry into ANC were being a teenager, living in an ethnic-minority community group, having a poverty certificate, and having a history of abortion. Analyses based on the behavioral model of Andersen were conducted in other countries such as Australia [17] and Belgium [28]. They reported similar findings.

Being a teenager was a predisposing characteristic related to late entry into ANC. Younger pregnant women, especially teenagers are more likely to have an unintended pregnancy. For this reason, they typically want to hide it from most people. They not only feel shame and guilt but also fear rejection from other people. Because of their relatively young age, they usually also lack information, experience, autonomy and resources to access ANC services. Such findings have been reported in other studies conducted in Ethiopia, Australia, Belgium, and the United States [17,28-30]. Younger pregnant women should be detected in their community and be advised by the health workers. Sexual education, education about pregnancy and about the benefits of antenatal care should be established in schools and communities.

Ethnic minority was another predisposing variable significantly associated with late entry into ANC. The factor of ethnicity was also reported in a study on ethnic disparities in Vietnam [31] and other countries [17,28,32]. People living in minorities may have traditional beliefs that delay the entry into ANC. Moreover, minorities usually have their own languages, which makes it difficult to communicate with health educators, leading to a lack of knowledge about ANC. Educational level was also correlated with the time of first ANC attendance, as observed in other studies in Vietnam [21] and in other countries [19,32,33]. Women with a higher level of education are more likely to appreciate the importance of early entry than the less educated ones. However, this was not significant in the multivariate analysis in our study.

Enabling factors associated with late initiation to ANC include the lack of health insurance and income [28]. Poverty certificate, which attests the low income of a household, were associated with late ANC usage. Low financial resources have been shown to similarly limit ANC usage in other studies [17,34,35]. In order to attend ANC, pregnant women have to pay for several services such as consultation, examination, ultrasound and also transportation to the ANC site. Cost for ANC can negatively affect poor pregnant women to early entry into ANC services. The Vietnamese health insurance is provided gratis to the poor population. Although it gives the poor free health care services, this does not appear to significantly improve the early entry into ANC. Health insurance does not cover the fee for transportation or the daily income that pregnant women lose for the day-off.

Pregnant women reporting a history of abortion came significantly later for ANC in our study. This might imply that they were not aware of possible underlying health issues surrounding their situation and did not perceive the risk for their current pregnancy. This is in agreement with the findings of a study conducted in Uganda [36]. Another study in Ethiopia also reported that pregnant women without a history of abortion were more likely to book ANC earlier [37]. In Vietnam, pre- and post-abortion counseling are not provided properly and routinely [38]. Such counselling usually focuses on the information of family planning and complications after abortion. The importance of early entry into ANC should be emphasized in healthcare education, especially when women have a history of abortion.

Although the district of Trang Bom is not representative of the whole country, it is representative of the urbanized Vietnam. Trang Bom has a good structure of healthcare at all levels. It has a stable socio-economic development, making it a suitable district for implementing research and generalizing some results to other settings.

Limitation

This study was conducted within communities, with the help of village health workers. Although they were trained for interviewing and recording of answers, some answers may have been mistaken at the beginning. Let us also note that the quality/content of first ANC attendance was not investigated in the present paper because it was not our objective. As the study was conducted in the district of Trang Bom, with an advanced roadway system, the generalization of our results to communities living in other settings could depend on their similarities with our research area.

Conclusion and Recommendations

The proportion of pregnant women entering late into ANC in rural areas remains higher than in urban areas. Maternal ethnicity, age, and poverty were associated with late entry into ANC, implying that inequalities still exist between women. On-time health education and the propagation of the importance of attending ANC early should focus on poor people, on women who have a history of abortion, on ethnic minorities, and on teenagers in order to promote significant early entry into antenatal care and therefore to improve maternal-andchild health.

Funding

This study was funded by the Belgian University Cooperation (http://www.ares-ac.be/fr/cooperation-au-developpement/paysprojets/ projets-dans-le-monde) through the PRD2012 collaborative project between Université catholique de Louvain, Université Libre de Bruxelles, Pham Ngoc Thach University of Medicine, Pediatric Hospital Number 2, and the Health Department of the province of Dong Nai.

Authors Contribution

NTTD participated in the design, carried out the study, performed the statistical analyses, and drafted the manuscript. TTT helped in the establishment of the study. NHD, TQD, and PG provided advice on the design of the study and the analytical strategy, and contributed to the manuscript revision. AR and NTD are head of the project; they provided advice on the structure, the data analysis and presentation, and supervised the manuscript redaction. No author has any financial or private interest in this research project. The corresponding author has full access to all the data in the study and has the final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgement

We thank the pregnant women who participated to the study for their time and collaboration. We thank the staff of the Commune Health Station and Health Centre of the District of Trang Bom for their cooperation and assistance during data collection.

References

- WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, The World Bank, Division tUNP (2014) Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2013.

- UNICEF, WHO, World Bank, UN-DESA Population Division (2015) Levels and trends in child mortality.

- Bhutta ZA, Das JK, Bahl R, Lawn JE, Salam RA, et al. (2014) Can available interventions end preventable deaths in mothers, new-born babies and stillbirths and at what cost? Lancet 384: 347-370.

- Carroli G, Rooney C, Villar J (2001) How effective is antenatal care in preventing maternal mortality and serious morbidity? An overview of the evidence. Paediatr Perinatal Epidemiol 15: 1-42.

- Darmstadt GL, Bhutta ZA, Cousens S, Adam T, Walker N, et al. (2005) Evidence-based, cost-effective interventions: How many newborn babies can we save? Lancet 365: 977-988.

- Giovanni Z, Regina M, Guarenti L, Franchi M (2006) Antenatal care in developing countries: The need for a tailored model. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 11: 15-20.

- WHO (2003) Antenatal care in developing countries. Promises, achievements and missed opportunities: An analysis of trends, levels and differentials, 1990-2001.

- Department of Reproductive Health and Research (2001) WHO Antenatal care randomized trial. Manual for the implementation of the new model, p: 42.

- Rosen MG, Merkatz IR, Hill JG (1991) Caring for our future: a report by the expert panel on the content of prenatal care. Obstet Gynecol 77: 782-787.

- National collaborating centre for women's and children's health (2008) Antenatal Care: Routine care for the healthy pregnant woman RCOG press, London.

- Public Health England (2010) Infectious diseases in pregnancy screening: Programme standards.

- Harcombe J, Armstrong V (2008) Antenatal screening. The UK NHS antenatal screening programmes: Policy and practice. InnovAit 1: 579-588.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2008) Antenatal care for uncomplicated pregnancies.

- National Committee for Population and Family Planning (1997) Vietnam demographic and health survey 1997. Hanoi, Vietnam.

- UNFPA (2012) Advocacy brief on MDG5b - Antenatal care in Vietnam. The United Nation, Vietnam.

- General statistic office of Vietnam (2012) Vietnam statistic yearbook. Ministry of health.

- Trinh LT, Rubin G (2006) Late entry to antenatal care in New South Wales, Australia. Reprod Health 3: 8.

- Adekanle DA, Isawumi AI (2008) Late antenatal care booking and its predictors among pregnant women in south-western Nigeria. Online Journal of Health and Allied Science 7: 4.

- Hussen SH, Melese ES, Dembelu MG (2016) Timely initiation of first antenatal care visit of pregnant women attending. J Pregnancy Child Health 5: 6.

- Babitsch B, Gohl D, von Lengerke T (2012) Re-revisiting Andersen’s behavioral model of health services use: A systematic review of studies from 1998–2011. Psycho Soc Med 9: 11.

- Trinh LT, Dibley MJ (2006) Antenatal care adequacy in three provinces of Vietnam: Long An, Ben Tre and Quang Ngai. Public Health Rep 121: 468-475.

- Glei DA, Goldman N, Rodriguez G (2003) Utilization of care during pregnancy in rural Guatemala: Does obstetrical need matter? Soc Sci Med 57: 2447-2463.

- Ministry of Health (2011) Health statistic yearbook. Hanoi, Vietnam, pp: 94-95.

- Andersen RM (1968) A behavioural model of families' use of health services, Center for Health Administration studies, University of Chicago.

- Andersen RM (1995) Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: Does it matter? J Health Soc Behav 36: 1-10.

- Tran TK, Gottvall K, Nguyen HD, Ascher H, Petzold M (2012) Factors associated with antenatal care adequacy in rural and urban contexts-results from two health and demographic surveillance sites in Vietnam. BMC Health Serv Res 12: 40.

- Wang W, Alva S, Wang S, Fort A (2011) Levels and trends in the use of maternal health services in developing countries. DHS comparative reports No 26. ICF Macro, Calverton, Maryland, USA.

- Beeckman K, Louckx F, Putman K (2010) Predisposing, enabling and pregnancy-related determinants of late initiation of prenatal care. Matern Child Health J 15: 1067-1075.

- Alderliesten ME, Vrijkotte TG, Wal MFV, Bonsel GJ (2007) Late start of antenatal care among ethnic minorities in a large cohort of pregnant women. BJOG 114: 1232-1239.

- Teshome A, Abebe A, Balcha B (2016) Assessment of timing of first antenatal care booking and associated factors among pregnant women who attend antenatal care at health facilities in Dilla town, Gedeo zone, southern nations, nationalities and peoples region, Ethiopia, 2014. J Pregnancy Child Health 3: 10.

- Tran TK, Nguyen CT, Nguyen HD, Eriksson B, Bondjers G, et al. (2011) Urban-rural disparities in antenatal care utilization: A study of two cohorts of pregnant women in Vietnam. BMC Health Serv Res 11: 120.

- LaVeist TA, Keith VM, Gutierrez ML (1995) Black/white differences in prenatal care utilization: An assessment of predisposing and enabling factors. Health Serv Res 30:43-58.

- Navaneetham K, Dharmalingam A (2002) Utilization of maternal health care services in Southern India. Soc Sci Med 55: 1849-1869.

- Ali AA, Osman MM, Abbaker AO, Adam I (2010) Use of antenatal care services in Kassala, eastern Sudan. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 10: 67.

- Ye Y, Yoshida Y, Harun-Or-Rashid M, Sakamoto J (2010) Factors affecting the utilization of antenatal care services among women in Kham District, Xiengkhouang province, Lao PDR. Nagoya J Med Sci 72: 23-33.

- Kisuule I, Kaye DK, Najjuka F, Ssematimba SK, Arinda A, et al. (2013) Timing and reasons for coming late for the first antenatal care visit by pregnant women at Mulago hospital, Kampala Uganda. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 13: 121.

- Belayneh T, Adefris M, Andargie G (2014) Previous early antenatal service utilization improves timely booking: Cross-sectional study at University of gondar hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. J Pregnancy, p: 7.

- PATH (2013) Strengthening the quality of abortion services in Vietnam

Relevant Topics

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 5288

- [From(publication date):

June-2017 - Aug 30, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 4119

- PDF downloads : 1169