Neural Tube Defect and Associated Factors in Bale Zone Hospitals, Southeast Ethiopia

Received: 14-Mar-2019 / Accepted Date: 09-May-2019 / Published Date: 16-May-2019

Abstract

Introduction: Neural Tube Defect (NTD) is related to failure of neural tube closure between 3rd and 4th weeks of embryo development. The cause of NTDs is not clearly stated, however, may factors like radiation, drugs, malnutrition, chemicals, genetic, maternal age, previous history of still birth, lack of Antenatal Care (ANC), consanguinity and any febrile illness during pregnancy were identified as contributing factors for development of NTDs. In spite of deficiency of folic acid in Ethiopia, data on factors of NTD were very limited in Africa in general and Ethiopia in particular, therefore this study was undertaken to identify associated factors with NTDs and provides shadow for future studies.

The objective of the present study is to identify patterns of neural tube defect and associated factors among newborn in four public hospitals in Bale Zone, Southeast Ethiopia.

Methods: Case control study design was conducted in four public hospitals at Bale Zone from October 2017 to February 2018. Total sample of 462 were included and convenience sampling method was implemented. Semi structured and pretested questioner was used to collect data.

Result: Maternal factors significantly associated with increased risk for NTDs were maternal age between 15-24 years (OR=4.78, 95%CI, 1.10-20.66), consanguineous marriage (OR=5.54, 95%CI, 1.47-20.87), being passive smokers (OR=11.08, 95%CI, 1.96-62.69), and Folic acid supplementation (OR=0.095, 95%CI, 0.031-0.285).

Conclusion: In present study, folic acid supplementation was identified as protective factor for NTDs, while, consanguinity, being passive smokers and women between the ages of 15-24 years, were the risk factors associated with NTDs.

Keywords: Neural tube; Defect; Consanguinity; Folic acid

Abbreviations

ANC: Antenatal Care; AOD: Adjusted Odds Ratio; CNS: Central Nervous System; CI: Confidence Interval; EPHI: Ethiopian Public Health Institute; ETB: Ethiopian Birr; IFA: Iron Folic Acid; LBW: Low Birth Weight; LMIC: Low and Middle Income Countries; MMWR: Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report; NNP: National Nutritional Program; NTD: Neural Tube Defect; OR: Odds Ratio; PPIP: Perinatal Problem Identification Program

Introduction

Neural tube defect (NTD) is related to failure of neural tube closure between 3rd and 4th weeks of embryo development [1]. The cause of NTDs is not clearly stated, however, many factors like radiation, drugs, malnutrition, chemicals, genetic, maternal age, previous history of still birth, lack of Antenatal Care (ANC), consanguinity and any febrile illness during pregnancy were identified as contributors for development of NTDs [2-4].

Anatomically, NTD can be classified into cranial and spinal defects. Cranial defects comprised anencephaly, encephalocele, and iniencephaly. On the other hand, spinal defects include meningocele, myelomeningocele and spina bifida occulta [5]. The spina bifida occulta could be due to vertebral column defects while the neural tube is normal in development [6].

Depending on the surface exposure or skin covering, the NTDs can be categorized as opened or closed defects [2]. Opened NTD is characterized by communication of brain and spinal cord or its meningeal covering with the external environment which includes anencephaly, spina bifida, iniencephaly and encephalocele. Nonetheless, in closed NTD there is no communication with external environment which includes spina bifida occulta, lipoma, diastematomyelia, diplomyelia [2,7].

Neural tube defects are characterized by incomplete closure of the spinal column and cranium. When newborns with NTDs survive, they will end up in lifelong disability as well as medical expense for their families [8]. For instance, study done in Florida revealed that about 70 cases of newborn with spina bifida were identified each year with an estimated cost of $44.5 million [9]. Besides, study done in United States the lifetime medical costs involved for each child with spina bifida is estimated at approximately $294,000.00 [10].

People born with spina bifida usually lacks acceptance in their communities. In Kenya stigmatization of neural tube defects has been documented affecting the quality of life of caring families [11].

A severe birth defect that has scientifically been shown to be avoidable is NTD [12]. A considerable number of NTDs occur as a result of insufficient intake of folic acid around the time of conception [9]. Recent study showed that only about 10% of NTDs are being prevented through folic acid fortification worldwide [13]. Despite this fact, nearly two-thirds of Ethiopian women are victim of folic acid deficiency [14].

Worldwide, more than 300,000 babies are born with NTDs each year, serious birth defects of the brain and spine are a significant cause of infant death and lifelong disability [13]. In Africa, it is said to affect approximately 1-3 per 1000 births annually [15]. According to study done in Tanzania NTDs was the highest prevalence form of birth defect (1/1000 births) among the selected external major structural defects [16].

In Ethiopia the prevalence of birth defect is 19 per 1000 births from which 30.87% is attributable to NTDs, which is the second common cause of birth defect [3,17]. According to study done in two teaching hospitals in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, the prevalence of neural tube defect is higher (6.1/1000 births) than reports from different studies in African countries [15,16,18].

In Ethiopia there are limited studies done on factors associated with NTDs, studies indicated regional variation on the occurrence of NTDs and folic acid deficiency [19,20]. Therefore this study was undertaken to identify factors associated with NTDs and provide baseline for future studies.

Methodology

Study design

A case control study design was used conducted among newborn in four public hospitals, in Bale Zone.

Sample size

The total sample size was 462 ( 42 cases and 420 controls) determined with Epi info version 7.1 using prevalence of exposure (alcohol intake of mothers) among control 9.8% OR=3.15 [4]. Convenience sampling method was employed to include all newborns with neural tube defect and ten consecutive newborns without NTDs delivered after each case.

Data collection procedure

Data were collected using structured questionnaire from relevant related studies, which include questions of socio-demographic, obstetric, medical, alcohol intake and smoking history and folic acid supplementation [21-23]. The questionnaire was prepared in English then translated into Amharic and Afan Oromo then back to English for consistence of translation.

Four data collectors (midwives) and four supervisors (head nurses of Maternity and labor ward) were recruited. The supervisors and data collectors were trained for two days on basic principles of data collection and on the questionnaire by the principal investigator [24]. Accordingly, the supervisors continuously followed the data collection process. Moreover, supervisors and investigators reviewed and cross collected data before analysis [25,26]. Finally, it was reported and discussed with the investigator on a daily basis throughout the data collection period.

Data quality assurance

To maintain data quality, data collectors were selected by their educational level and experience of data collection. They were trained about data collection tool and purpose of the study for two days. The questionnaire was developed by the investigator based on questions used in previous peer reviewed published studies [26,27]. Pretest study was conducted at nearby health center to see for the accuracy of responses, language clarity, and appropriateness of the tools. The collected data had been cleared by the investigator and supervisor on daily basis during data collection.

Data management and data analysis

The collected data were coded, manually checked and entered by using Epi-data version 3.1 prior to analysis, the data were exported from Epi-data to SPSS Version 21 and was checked for missing values. Descriptive statistics and numerical summary measures were presented by using frequencies distribution tables and graphs (diagrams). Univariate analysis was employed to examine the relationship between the outcome variable and independent variable. Those variables with (p ≤ 0.2) in the univariate analysis was entered into multivariable logistic regression model by using adjusted odds ratio (AOR) and Confidence Intervals (CI). This helps to identify important determinants by controlling possible confounding effect [28,29]. Variables with p-value<0.05 were considered as statistically significant. Hosmer- Lemeshow goodness of-fit test was used to test the fitness of model.

Ethical consideration

Ethical clearance was obtained from Ethical Review Committee of University of Gondar. Ethical clearance obtained from University of Gondar submitted to Bale Zone Health Office. Bale Zone Health Office was informed about the objectives and support letter from Bale Zone Health Office was submitted to the respective hospital CEOs. Written consent was obtained from each selected mothers to confirm willingness. Each respondent was informed about the aim of the study. They were also informed that all data obtained from them will be kept confidential by using codes instead of any personal identifiers and is meant only for the purpose of the study.

Results

In the present study, a total of 462 newborns delivered from October 2017 to February 2018 in Bale Zone were included. Out of them 42 were newborns with NTD and 420 newborns without NTDs. Maternal age ranges from 16 to 45 years with mean age of 30.29 ± 7.27 year. The mean age of mothers in the control group was 30.83 ± 7.22 year and in case group was 29.86 ± 5.32 year.

Socio-demographic predictors

Univariate analysis of maternal socio-demographic characteristics revealed that, maternal age between 15-24 year of age was significantly associated with increased risk of NTDs (OR=4.78, 95%CI, 1.10-20.66) [30-32]. Attending secondary school was identified to be protective for NTDs both in mothers and their husbands (OR=0.228, 95%CI, 0.096- 0.547) and (OR=0.171, 95%CI, 0.07-0.41), respectively. Regardless of the statistically non-significant difference, the number of mothers attending college and above was slightly higher among controls 118 (28.1%) than mothers of newborns with NTDs 7(16.7%) [33-35]. Marital status, occupational status, monthly family income, religion and ethnicity were not significantly associated with NTDs (Table 1).

| Independent Variables | Dependent Variable | Total | Bivariate Analysis | |||

| Cases (%) | Controls (%) | N (%) | OR (CI) | P value | ||

| Age of mothers in years | = 35 | 23 (54.8) | 224 (53.3) | 247 (53.5) | 1 | - |

| 25-34 | 17 (40.4) | 103 (24.5) | 120 (26.0) | .622 (.319-1.21) | 1.64 | |

| 15-24 | 2 (4.8) | 93 (22.2) | 95 (20.5) | 4.77 (1.10-20.66) | .036* | |

| Educational level of husband | No formal education | 7 (17.1) | 128 (38.2) | 135 (35.9) | 1.25 (.44-3.56) | 0.675 |

| primary school | 6 (14.6) | 40 (12) | 46 (12.2) | .456 (.15-1.39) | .168* | |

| secondary school | 20 (48.8) | 50 (14.9) | 70 (18.6) | .171 (.07-.41) | .000* | |

| college and above | 8 (19.5) | 117 (34.9) | 125 (33.3) | 1 | - | |

| Occupational status of husband | Farmer | 24 (58.5) | 162 (48.4) | 186 (49.5) | .438 (.15-1.31) | .141* |

| Governmental employee | 11 (26.8) | 102 (30.4) | 113 (30.1) | .592 (.181-1.94) | 0.387 | |

| NGO employee | 2 (4.9) | 9 (2.7) | 11 (2.9) | .290 (.046-1.820) | .187* | |

| Private business | 4 (9.8) | 62 (18.5) | 66 (17.5) | 1 | - | |

| Educational status of mothers | No formal education | 0 | 123 (29.3) | 123 (26.6) | - | |

| Primary school | 8 (19.0) | 75 (17.9) | 83 (19.0) | .556 (.194-1.597) | 0.276 | |

| Secondary school | 27 (64.3) | 104 (24.8) | 131 (28.4) | .228 (.096-.547) | .001* | |

| Collage and above | 7 (16.7) | 118 (28.1) | 125 (27.0) | 1 | - | |

| Religion of mothers | Orthodox | 11 (26.2) | 147 (35.0) | 158 (34.2) | 1 | - |

| Muslim | 29 (69.0) | 197 (46.9) | 226 (48.9) | .508 (.246-1.051) | .068* | |

| Ethnicity of mothers | Protestant | 2 (4.8) | 76 (18.1) | 78 (16.9) | 2.844 (.62-13.16) | .181* |

| Oromo | 36 (85.7) | 328 (78.1) | 364 (78.8) | 1 | - | |

| Monthly family income | <810 ETB | 13 (30.9) | 106 (25.2) | 119 (25.8) | 1 | - |

| 810-1620 ETB | 18 (42.9) | 120 (28.6) | 138 (29.9) | .818 (.38-1.748) | 0.603 | |

| >1620 ETB | 11 (26.2) | 194 (43.8) | 205 (42.2) | 2.051 (.89-4.74) | .093* | |

*P-value = 0.2 used to identify candidate variables had been entered into multivariate analysis.

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of mothers of newborn with NTDs and controls in Bale Zone Hospitals, Southeast Ethiopia, 2018.

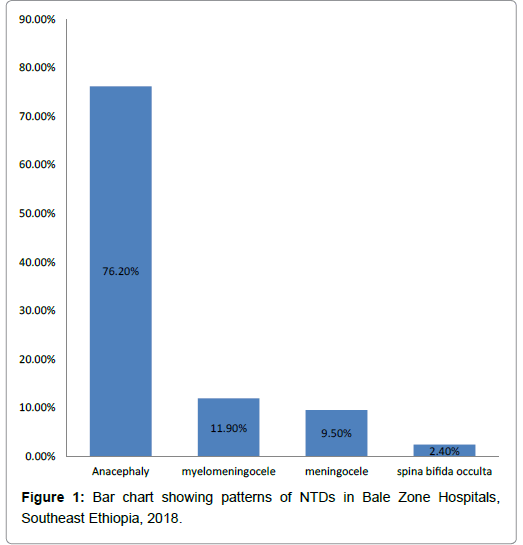

Patterns of neural tube defects

Occurrence patterns of NTDs identified were anencephaly, myelomeningocele, meningocele and spina bifida occulta accounts for (32 (76.2%), 5(11.9%), 4(9.5%) and 1 (2.4%)), respectively (Figure 1).

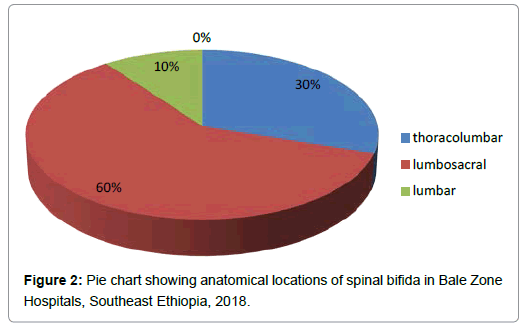

Anatomically, the locations of spina bifida were lumbosacral 6 (60%), thoracolumbar 3 (30%) and lumbar 1 (10%) (Figure 2).

Obstetric history of mothers

This study revealed that higher number of primigravidas give birth to NTD newborns compared to control (35%, 21%, p=0.028), respectively. Primiparous were significantly higher among mothers of newborn with NTD as compared to controls (62.9% and 23.1% p=0.000), respectively [37,38]. There was no significant difference between cases and control mothers on the history of still birth, previous history of child with NTDs and a family history of NTDs (Table 2).

| Independent Variables | Dependent Variable-NTD | Total | Univariate Analysis | |||

| Cases (%) | Controls (%) | N (%) | OR (CI) | P-value | ||

| Gravidity | 1 | 15 (35.7) | 88 (21) | 104 (22.5) | 1 | |

| 02-Apr | 19 (45.2) | 252 (60) | 271 (58.7) | 2.24 (1.09-4.59) | .028* | |

| 05-Oct | 8 (19) | 79 (17.9) | 87 (18) | 1.580 (.635-3.931) | 0.325 | |

| Parity | 1 | 26 (62.9) | 97 (23.1) | 123 (26.6) | 1 | - |

| 02-Apr | 10 (23.8) | 252 (60) | 262 (56.7) | 6.76 (3.14-14.53) | .000* | |

| 05-Oct | 6 (14.3) | 71 (16) | 77 (15.8) | 2.99 (1.17-7.67) | .022* | |

| History of still birth | Yes | 3 (7.1) | 41 (9.8) | 44 (9.5) | 1.406 (.416-4.75) | 0.583 |

| No | 39 (92.9) | 379 (90.2) | 418 (90.5) | 1 | - | |

| History of Abortion | Yes | 20 (47.6) | 42 (10) | 59 (12.8) | .126 (.082-.981) | .123* |

| No | 22 (52.3) | 378 (90) | 403 (87.2) | 1 | - | |

| Previous history of child with NTDs | Yes | 1 (2.4) | 5 (1.2) | 6 (1.3) | .494 (.056-4.330) | 0.524 |

| No | 41 (97.6) | 415 (98.8) | 456 (98.7) | 1 | - | |

| Family history of NTDs | Yes | 5 (11.9) | 21 (5) | 26 (5.6) | .389 (.139-1.093) | .073* |

| No | 37 (88.1) | 399 (95) | 436 (94.4) | 1 | - | |

*P-value = 0.2 used to identify candidate variables had been entered into multivariate analysis.

Table 2: Obstetric history of mothers of NTD newborns and controls in Bale Zone Hospitals, Southeast Ethiopia, 2018.

Exposure of mothers to recognized risk factors

This study indicated that consanguineous marriage and being passive smokers were proven to be risk factors for NTDs (OR=4.9, 95% CI, 1.49- 16.17) and (OR= 6.09, 95% CI, 1.44-25.64), respectively. Maternal history of history of exposure to toxins and radiation were not significantly associated with NTDs [39]. History of medical illness, medical drug use and alcohol intake were not shown to have association with NTDs (Table 3).

| Independent Variables | Dependent Variable-NTD | Total | Univariate Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases (%) | Controls (%) | N (%) | OR (CI) | P-value | ||

| Medical illness | Yes | 10 (23.8) | 101 (24.1) | 111 (24) | 1.01 (.48 - 2.13) | 0.973 |

| No | 32 (76.2) | 319 (75.9) | 351 (76) | 1 | - | |

| Drug uses during pregnancy | Yes | 9 (21.4) | 59 (14) | 68 ( 15) | .589 (.27-1.29) | .188* |

| No | 33 (78.6) | 361 (86) | 394 (85) | 1 | - | |

| Exposure to radiation | Yes | 2 (4.8) | 9 (2.1) | 11 (2.4) | .438 (.09-2.08) | 0.302 |

| No | 40 (95.2) | 411 (97.9) | 451 (97.6) | 1 | - | |

| Exposure to chemicals like pesticides | Yes | 1 (2.4) | 2 (0.5) | 3 (.7) | .196 (.017-2.21) | .187* |

| No | 41 (97.6) | 418 (99.5) | 459 (99.3) | 1 | - | |

| passive smoker | Yes | 2 (4.8) | 98 (23.3) | 100 (21.6) | 6.09 (1.44-25.64) | .014* |

| No | 40 (95.2) | 322 (76.7) | 362 (78.4) | 1 | - | |

| History of alcohol in take | Yes | 6 (14.3) | 49 (11.7) | 55 (11.9) | .792 (.32-1.98) | 0.618 |

| No | 36 (85.7) | 371 ( 88.3) | 407 (88.1) | 1 | - | |

| Consanguinity | Yes | 3 (7.1) | 115 (27.4) | 118 (25.5) | 4.9 (1.49-16.17) | .009* |

| No | 39 (92.9) | 305 (71.6) | 344 (74.5) | 1 | - | |

Mothers history of ANC follow up and folic acid supplementations

As shown in the univariate analysis, mothers supplemented folic acid were 88% less likely to give birth to newborn with NTDs (OR=0.115, 95%CI, 0.044-0.298). Even though, ANC follow up was slightly higher among controls than cases, it was not proved to be protective for NTDs (OR=5.53, 95% CI, 2.64-11.55). Initial time of ANC follow up within the first 6 weeks was higher among control mothers when compared with mothers of newborn with NTDs (13.8% vs 4.8%), respectively. However, the difference was not statistically significant (Table 4).

| Independent Variables | Dependent Variable NTD | Total | Univariate Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases (%) | Controls (%) | N (%) | OR (CI) | p-value | ||

|

ANC follow up |

Yes | 10 (23.8) | 266 (63.3) | 276 (59.7) | 5.53 (2.64-11.55) | .000* |

| No | 32 (76.2) | 154 (36.7) | 186 (40.3) | 1 | - | |

|

Folic acid supplementation |

Yes | 37 (88.1) | 193 (46) | 230 (49.7) | .115 (.044-.298) | .000* |

| No | 5 (11.9) | 227 (54) | 232 (50.3) | 1 | - | |

* P-value = 0.2 used to identify candidate variables had been entered into multivariate analysis.

Table 4: Folic acid supplementations and ANC follow up among mothers newborn with NTDs and controls in Bale Zone Hospitals, Southeast Ethiopia, 2018.

This study revealed that number of male newborns with NTDs were slightly higher than newborns without NTDs (57.1% vs 49.1%, respectively), while duration of pregnancy was shorter (28-35 weeks) in cases than controls (66.7% vs 16.0%) [40]. In spite of this difference both of parameters were not proven to have association with NTDs. Very low birth weight (<1500 mg) was higher among case than in controls (21.4% vs 8.1%, respectively) (Table 5).

| Independent Variables | Dependent Variable-NTD | Total | Univariate Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases (%) | Controls (%) | N (%) | OR (CI) | P-value | ||

| Gestational age | 28-36 | 13 (31) | 94 (22.4) | 107 (35.4) | .873 (.391-1.947) | 0.739 |

| 37-38 | 15 (35.7) | 210 (50) | 225 (79) | 1.69 (.79-3.62) | .178* | |

| 39-42 | 14 (33.3) | 116 (27.4) | 130 (43.6) | 1 | - | |

| Wight of new born | <1500 gm | 9 (21.4) | 34 (8.1) | 43 (9.3) | .391 (.172-.888) | .025* |

| 1500-2499 gm | 1 (2.4) | 77 (18.3) | 78 (16.9) | 7.97 (1.07-59.27) | .042* | |

| >2500 gm | 32 (76.2) | 309 (73.6) | 341 (73.8) | 1 | - | |

| Sex of newborn | Male | 24 (57.1) | 206 (49.1) | 230 (49.8) | .722 (.381-1.37) | 0.319 |

| Female | 18 (42.9) | 214 (50.9) | 232 (50.2) | 1 | - | |

*P-value = 0.2 used to identify candidate variables had been entered into multivariate analysis

Table 5: Neonatal characteristics among mothers of newborn with NTDs and controls in Bale Zone Hospitals, Southeast Ethiopia, 2018.

In general, both bivariate and multivariate analysis demonstrated statistically significant association of NTDs with that of maternal age, passive smokers, consanguineous marriages, supplementation of folic acid and maternal previous history abortion. Folic acid supplementation (OR=0.095, 95%CI, 0.031-0.285) was protective factors for NTDs. While, consanguineous marriage and being passive smoker were risk factors for NTDs (OR=5.54, 95%CI, 1.47- 20.87) and (OR=11.08, 95%CI, 1.96-16.69), respectively. In spite of having significant association maternal previous history of abortion was not proved to be risk for NTDs (OR= 0.072, 95%CI, 0.026-.197) (Table 6).

| Independent variables | Dependent variable-NTD | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases (%) | Controls (%) | N (%) | AOR (CI) | P-value | ||

| Mother age | = 35 | 23 | 224 | 247 | - | - |

| 25-34 | 17 | 103 | 120 | .622 (.319-1.21) | 1.64 | |

| 15-24 | 2 | 93 | 95 | 4.77 (1.10-20.66) | .036* | |

| Religion of mothers | Orthodox | 11 | 147 | 158 | 1 | - |

| Muslim | 29 | 197 | 226 | .39 (.15-.98) | 0.045 | |

| Protestant | 2 | 76 | 78 | 2.00 (.36-11.15) | 0.427 | |

| Consanguinity | Yes | 3 | 115 | 118 | 5.54 (1.47-20.87) | 0.011 |

| No | 39 | 305 | 344 | 1 | - | |

| Drug uses during pregnancy | Yes | 9 | 59 | 68 | .114 (.01-2.60) | 0.174 |

| No | 33 | 361 | 394 | 1 | - | |

| Exposure to toxin and Chemicals | Yes | 1 | 2 | 3 | .450 (.148-1.371) | 0.167 |

| No | 41 | 418 | 459 | 1 | - | |

| Passive smokers | Yes | 2 | 98 | 100 | 11.08 (1.9- 16.6) | 0.007 |

| No | 40 | 322 | 362 | 1 | - | |

| History of abortion | Yes | 20 | 42 | 59 | .0126 (.026-1.2) | 0.123 |

| No | 22 | 378 | 403 | 1 | - | |

| Family history of NTDs | Yes | 5 | 21 | 26 | .330 (.056-1.961) | 0.223 |

| No | 37 | 399 | 436 | 1 | - | |

| ANC follow up | Yes | 10 | 266 | 276 | 1.587 (.42-6.05) | 0.499 |

| No | 32 | 154 | 186 | 1 | - | |

| Folic acid supplementation | No | 37 | 193 | 230 | .095 (.031-.285) | 0 |

| Yes | 5 | 227 | 232 | 1 | - | |

| Weight of new born | <1500 gm | 9 | 34 | 43 | .287 (.101-.812) | 0.019 |

| 1500-2499 gm | 1 | 77 | 78 | 4.16 (.49 - 34.79) | 0.189 | |

| >2500 gm | 32 | 309 | 341 | 1 | - | |

*P-value <= 0.05 is considered to be statistically significant.

Table 6: Multivariate binary logistic regression analysis table in Bale Zone, Southeast Ethiopia, 2018.

Discussion

Our finding indicated that mothers between the ages of 15-24 years were 4.9 times more likely to give birth of newborns with NTDs as compared with those older than or equal to 35 years of age. Similarly study done in Sudan revealed that mothers age less than 25 years were higher among cases of NTDs [5].

Consanguineous marriage found to be significantly associated with NTDs. The finding of this study, was mothers who had history of consanguinity were 6 times more likely to give birth to newborn with NTDs, this finding has agreement with study done in Egyptian, Sudan, Kashmir and Mosul city reported significant association between the consanguinity and NTDs [5,11,20,36]. The possible reason is that consanguinity is associated with genetic mutation caused by inbreeding and cause NTDs.

The result that we found revealed mothers who have previous history of abortion were 93% less likely to give birth of newborn with NTDs, is in contrast with study done in Iran revealed that mothers history of abortion were 5 times more likely to give birth to newborn with NTDs [4].

Folic acid supplementation was found to be protective for NTDs. The finding in the present study revealed mothers who were supplemented with folic acid was 91% less likely to give birth of newborn with NTDs. This in inline with the study conducted in United State and Geneva, Switzerland that reported folic acid supplement taken periconceptionally reduces the risk of NTDs by at least 50% [34,35]. The present study is also in agreement with the study done in Northern Iran revealed that folic acid consumption prior to pregnancy and during early pregnancy reduce risk of NTDs by 70 percent [24].

The finding of Present study indicated that mothers who were exposed to smoker (passive smoking) were 11 times more likely to give birth of child with NTDs as compared with mothers who were not exposed. Which is similar with study done in Italy that showed smoking were significantly associated with NTDs [4].

Patterns of NTDs tend towards more severe and lethal forms with highest being anencephaly 32(76.2%), followed by myelomeningocele 5(11.9). On the other hands, study done in Sudan and Nigeria reported myelomeningocele account (47.7%, 76.9%), followed by anencephaly (17.5% , 15.5%), respectively [41,42]. This difference is probable explained by geographical variation which affects NTD patterns.

Conclusion

This study revealed that consanguinity, maternal age between 15-24 years and passive smoker were risk factors associated NTDs. Therefore health education is mandatory for reproductive age group women on the risks of consanguinity and passive smoking.

Folic acid supplementation was identified to be protective for NTDs, since health facilities needs to consider folic acid supplementation for reproductive age groups women and encourage reproductive age women to have medical consultation prior to pregnancy.

The patterns of NTDs were identified with the majority being of the lethal type anencephaly followed by myelomeningocele.

Declarations

Availability of data and materials: The dataset analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests: We have no competing interests.

Acknowledgements: We would like to be grateful to midwifes and nurses working at Madda Walabu University Goba Referral Hospital, Robe Hospital, Delo Mena Hospital and Gindhir Hospital for their support during data collection period. We would like to thanks medical directors and managers of respective hospitals for their support. We would also like to extend our thanks to all respondents for agreeing to participate in the study. Finally, we want to thanks Madda Walabu University and University of Gondar for their supported.

References

- Sadler TW (2013) Langman’s medical embryology. 13th Edition. Pp: 294-326.

- Behrman RE, Kisman SL, Johnston M (2015) Nelson text book of pediatrics. 20th edition. 2: 2803-2811.

- Kheir A, Eisa WMH (2015) Neural tube defects, clinical patterns, associated risk factors and maternal awareness in Khartoum State, Sudan. J Med Med Res 3: 1-6.

- Marco PD, Merello E, Calevo MG, Mascelli S, Cama A, et al. (2010) Maternal periconceptional factors affect the risk of spina bifida-affected pregnancies: An Italian case-control study. Childs Nerv Syst 27: 1073-1081.

- Elsheikh GEA, Ibrahim SA (2009) Neural tube defects in omdurman maternity hospital, Sudan. Khartoum Med J 2: 185-190.

- Hegazy A (2004) Clinical Embryology for medical students and postgraduate doctors. Lambert Academic Publishing, Berlin.

- Yerby MS (2003) Clinical care of pregnant women with epilepsy: Neural tube defects and folic acid supplementation. Int Leag Againest Epilepsia 44: 33-40.

- Klotz JB, Pyrch LA (1998) A case-control study of neural tube defects and drinking water contaminants Pp: 3-147.

- Black RE, Victora CG, Walker SP, Bhutta ZA, Christian P, et al. (2013) Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Matern Child Nutr 13: 1-8.

- Aguiar MJB, Campos AS, Aguiar RALP, Lana AMA, Magalhães RL, et al. (2003) Neural tube defects and associated factors in liveborn and stillborn infants. J Pediatr 79: 129-134.

- Githuku JN, Azofeifa A, Valencia D, Ao T, Hamner H, et al. (2014) Assessing the prevalence of spina bifida and encephalocele in a Kenyan hospital from 2005-2010: Implications for a neural tube defects surveillance system. Pan Afr Med J 18: 60.

- WHO (2016) Neural tube defects. Departement of Health Information and Research, WHO, Geneva.

- CDC (2012) Neural tube defects by national center on birth defects and developmental disabilities annual report CDC.

- Head J, Getachew B (2014) Technical requirements for the fortification of wheat flour in Ethiopia. Fulbright-Inst Int Educ. Pp: 1-76.

- Alhassan A, Adam A, Nangkuu D (2017) Prevalance of neural tube defect and hydrocephalus in Northern Ghana. J Med Biomed Sci 6: 18-23.

- Kishimba RS, Mpembeni R, Mghamba JM, Goodman D, Valencia D (2015) Birth prevalence of selected external structural birth defects in four hospitals in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. J Glob Health 5: 1-6.

- Taye M, Afework M, Fantaye W, Diro E, Worku A (2016) magnitude of birth defects in central and Northwest Ethiopia from 2010-2014: A descriptive retrospective study. PLoS One 11: 1-12.

- Sorri G, Mesfin E (2015) Patterns of neural tube defect at two teaching hospitals in Addis Ababa. Ethiop Med J 53: 119-126.

- Zaganjor I, Sekkarie A, Tsang BL, Williams J (2016) Describing the prevalence of neural tube defects worldwide: A systematic literature review. PLoS One 11: 1-31.

- Central Statistics Agency (2016) Ethiopia demographic and health survey.

- Laamiri FZ, Elammari L, Mrabet M, Taboz Y, Benkirane H, et al. (2014) Prevalence of neural tube closure defects and oro-facial clefts , during three consecutive years ( 2012-2014 ) in 20 public hospitals in Morocco. Pp: 1-6.

- Mobasheri E, Keshtkar A, Golalipour MJ (2010) Maternal folate and vitamin b 12 status and neural tube defects in Northern Iran: A case control study. Iran J Pediatr 20: 167-173.

- Pocock L, Rezaeian M, Pocock L (2017) Congenital anomalies: Overview and a brief report on promising new research. World Fam Med East J Fam Med 15: 1-7.

- WHO (2010) Community genetics services in low and middle-income countries. Geneva, Swezerland.

- Williams J, Mai CT, Mulinare J (2015) National birth defects prevention month and folic acid awareness week. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 64: 1-1.

- Abdulhadi S (2018) Association between genetic inbreeding and disease mortality and morbidity in Saudi population. J Investig Genomics 5: 1-8.

- Aly EAH, Abd-manaf MH (2013) Prevalence and risk factors for major congenital anomalies among egyptian women: A four-year study. Med J Cario Univ 81: 757-762.

- Taboo ZA (2012) Prevalence and risk factors for congenital anomalies in mosul city. Iraqi Postgrad Med J

- Laharwal MA, Sarmast AH, Ramzan AU, Wani AA, Malik NK, et al. (2016) Epidemiology of the neural tube defects in Kashmir Valley. Surg Neurol Int. 7: 35.

- Motah M, Moumi M, Ndoumbe A, Ntieafac C, Djienctheu VDP (2017) Pattern and management of neural tube defect in Cameroon. Open J Mod Neurosurg 7: 87-102.

- Frey L, Hauser WA (2003) Epidemiology of neural tube defects. Epilepsia 44: 4-13.

- Salbaum1 JM, Kappen C (2010) Neural tube defect genes and maternal diabetes during pregnancy. Birth Defect Reserch Clin Teratol 88: 601-611.

- Chen C (2005) Congenital malformation associated with maternal diabetes. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol 44: 1-7.

- Carmichael SL, Shaw GM, Schaffer DM, Laurent C, Selvin S (2003) Dieting behaviors and risk of neural tube defects. Am J Epidemiol 158: 1127-1131.

- Afshar M, Golalipour MJ, Farhud D (2006) Epidemiologic aspects of neural tube defects in South East Iran. Neurosci 11: 289-292.

- Catherine P, Jane F, Kay E, Bertie L, Judith S, et al. (2010) Termination of fetal abnormality. R Coll Obstet Gynaecol.

- Salih MA, Murshid WR, Mohamed AG, Ignacio LC, de Jesus JE, et al. (2014) Risk factors for neural tube defects in Riyadh City, Saudi Arabia: Case-control study. Sudan J Pediatr 14: 49-60.

- Talebian A, Soltani B, Sehat M, Zahedi A, Noorian ATM (2015) Incidence and risk factors of neural tube defects in Kashan, Central Iran. Iran J Child Neurol 9: 50-56.

- Omer IM, Abdullah OM, Mohammed IN, Abbasher LA (2016) Research: Prevalence of neural tube defects Khartoum, Sudan August 2014-July 2015. BMC Res Notes 9: 16-19.

Citation: Atlaw D, Worku A, Taye M, Woldeyehonis D, Muche A (2019) Neural Tube Defect and Associated Factors in Bale Zone Hospitals, Southeast Ethiopia. J Preg Child Health 6:412.

Copyright: © 2019 Atlaw D, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Usage

- Total views: 5154

- [From(publication date): 0-2019 - Dec 10, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 4064

- PDF downloads: 1090