Review on Treatment of Substance Use Disorders

Received: 10-Nov-2017 / Accepted Date: 27-Nov-2017 / Published Date: 04-Dec-2017 DOI: 10.4172/2155-6105.1000353

Abstract

Services for mental and substance use disorders have typically been neglected, and in many countries segregated from mainstream health care with resources allocated not commensurate with the burden. The attention given to mental and substance use disorders cannot be compared to other diseases such as HIV/AIDS, Malaria, Cancer, and Diabetes among others. Mental and substance use disorders account to about 7.4% of disease burden worldwide. These disorders are responsible for more of the global burden than HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis, diabetes, or transport injuries. The increasing number of cases of SUDs globally presents a public health challenge that requires effective evidence based interventions. One of the major challenges is inadequate treatment for SUDs which mostly plague developing countries. It may be difficult to measure the efficacy of treatment as a result of unique patient characteristics that contribute to person’s treatment experience. Care factors such as duration of treatment and length of stay have been studied as having influence on the outcome of treatment. Others include patient and environmental factors. Globally, poor treatment outcomes mostly reported include dropout rates as high as 90%; relapse rates as high as 91% and high after treatment mortality rates. Research findings have identified many evidence-based treatment strategies for managing substance use disorders, nevertheless there is a gap that continues to exist, that of a lack of success of effective interventions to be spread and implemented so as to improve the lives of those affected. Other studies have also reported these differences in the outcomes and effectiveness of treatment of substance use disorders. There is need for enhanced interventional research that aims at providing an overview of conceptual issues relating to factors that influence treatment outcomes and identifying gaps and directions for improving treatment and treatment outcomes. The fundamental objective of enhanced research in substance use treatment is to reduce the increasing prevalence rates of substance use disorders.

Keywords: Acquired immune deficiency syndrome; Interpersonal therapy; Trans-theoretical model; Substance use

Abbreviations

AIDS: Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome; APA: American Psychiatric Association; ASAM: American Society for Addiction Medicine; CBT: Cognitive Behavior Therapy; HIV: Human Immune-Suppression Virus; IPT: Interpersonal Therapy; MET: Motivational Enhancement Therapy; MMT: Methadone Maintenance Treatment; SUDs: Substance Use Disorders; TSF: The 12-Step Facilitation; TTM: Trans-Theoretical Model; US: United States; UN: United Nations; UNODC: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime; WHO: World Health Organization; UKDPC: United Kingdom Drug Policy Commission

Introduction

Mental and substance use disorders will be the leading cause of disability worldwide by the year 2020 [1]. In recent years, the prevalence of mental and substance use disorders (SUDs) has been reported to be on the increase around the world. An increase of 37.6% in the global burden of diseases was reported between 1990 and 2010 [2].

Using a risk factors approach to the global burden of diseases, the proportion of the total global burden of disease attributable to specific SUDs has increased by 57% for illicit drug use (cannabis, opioids, amphetamines, and injection drug use), 32% for alcohol use, and 3% for tobacco use [3].

The UN World Drug Report [4] indicates that 230 million people use alcohol and other substances at least once a year while 27 million people are addicted; the report further indicates that substance abuse attributes to more than 0.2 million deaths every year and moderate to severe disability of 11.8 million people.

To counteract the global challenge of substance use disorders, different addiction treatment models continue to be developed. However, there is a gap between research, innovations and their adoption and implementation. This gap is wider in low-and-middle income countries especially in Africa, due to limited access to empirically supported treatments and a shortage of trained health workers to deliver evidence-based interventions [5,6].

Substance use disorders have been recognized as an escalating problem mostly affecting developing countries [7]. However, the exact prevalence of substance use disorders is difficult to attain, generally due to the developing countries limited capacity to conduct national surveys [8]. The strengthening of the prevention and treatment of substance abuse, including narcotic drug abuse is target 3.5 of the sustainable development goals. Therefore, prevention, treatment, care, recovery, rehabilitation and social reintegration measures and programmes all play a role in addressing the problem of drug use and reducing the negative health impact on society [9].

Walker describes treatment of substance use disorders as a focused change process [10], targeting the reduction of substance use, sustained abstinence, prevention of relapse (frequency and severity) and enhancing adaptive functioning. Treatment is delivered in various settings, lasting from a few months to several years depending on an individual’s needs and resources available [11]. Cases that are severe and intractable are the ones that enter treatment [12] with many cases accessing treatment during a crisis, such as acute intoxication or overdose, an accident or acute exacerbation of another health condition that is caused by substance use [13].

Interventions are often ineffective with poor treatment outcomes ranging from relapses, readmissions, drop outs and mortalities. Relapse rates as high as 90% have been reported in different countries [12,14,15]. Progress of most cases experience cycles of repeated treatments, relapses and recovery that may span for years which may lead to stable recovery, permanent disability or death [16-26].

Treatment of substance use disorders in most developing countries is often limited in nature and lack the follow-up and support that are crucial in assuring lasting sobriety. Most treatment and rehabilitation centers in these countries focus solely on detoxifying the patient and nothing else. Most of them lack the safeguards that facilities in developed countries such as US provide. In general, mental health care is limited in developing countries where substance use disorders are still not considered to be linked to mental illness [27].

Discussion

The trans-theoretical model

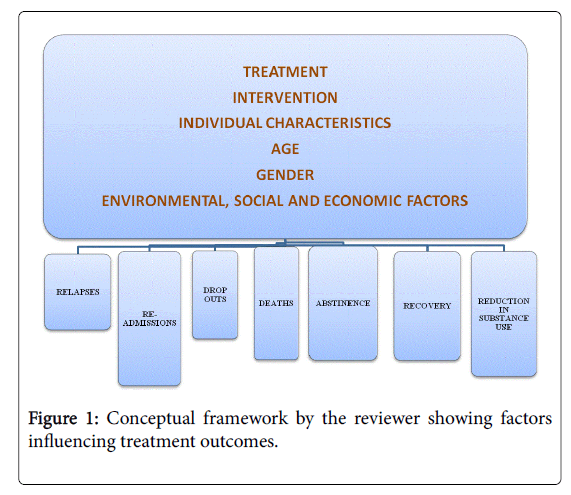

The trans-theoretical model (TTM) illustrates how alcohol and substance addiction treatment models, addicts’ individual characteristics, age and gender as well as environmental, social and economic factors impact on treatment outcomes. This model was proposed by Prochaska and DiClemente in 1983 [28]. This is a stages of change model adopted as a guideline for clinical interventions [29]. The model outlines the behavior change process especially in addictive behaviors [30,31]. It is based on experimental data from individuals with nicotine dependence that attained smoking cessation without enrolling for treatment [31,32].

It emphasizes the importance of a broader picture of an individual, allowing a more accurate evaluation of the patient condition. This is can be compared to the historic conception that success or failure in changing addictive behavior is a function of denial [31,32].

It describes behavior change by understanding the factors that distinguish between success and failure: at every step of change, success is linked to accomplishment of a task, translating to better engagement with targets in the next step.

Intentional behavior change refers to alterations in addictive behavior linked to substance use disorders. Change of behavior is critical for the success of treatment. Intentional change is not instant; depending on the dynamic changes presented by an individual over time in relation to motivational stage. It comprises of four perspectives: stage; processes; context; and signs of change [31,33,34]. Movements are cyclic rather than linear, and individuals can transit into and out of earlier or later stages until achieving behavioral consistency and stability.

Pre-contemplation: An individual shows no intention to change for about six months. An individual is still in denial that the behavior is a problem, or the problem has subsided so that the individual avoids facing any need to change. If the individual requests for treatment, it is usually as a result of external motivation, which may result in temporary changes in behavior. At this stage, the main task is to become conscious of the existence of a problem and of the need to change addictive behavior. The best techniques are psycho-educational, with individualized information and feedback.

Contemplation: This stage is characterized with consideration for change, but without a commitment to action. Ambivalence is a relevant characteristic at this stage. The benefits to be achieved must exceed the benefits of the negative behavior, be sufficient, according to the individual, to justify the changes and expected losses from the change of behavior that will determine progression to the subsequent level. The first strategy aims at motivating the individual to act on their choice and the positive benefits that will result from the change and allow for self-evaluation, analysis of the individual context as well as the strengthening of self-efficacy.

Preparation: The patient shows commitment to action. The task to be accomplished at this level is to strengthen the commitment and determine an action plan in relation to the individual context. The interventions might be directed towards the creation of this plan, considering a number of alternatives raised during the therapy process, so that the individuals select the alternative that is best for them and consequently commit to their decision.

Action: This is the first step towards changing the previous patterns whereby the individual is engaged adopting a new attitude. New behavior patterns may be established in about three to six months, modified and discontinued. The task in focus is to implement the necessary changes in as per the action plan. Significant interventions may consider regular review of the plan or re-establish the commitment to change [31].

Maintenance: Sustaining and integrating new habits. The aim is to avoid relapses and consolidate the gains made in the previous stage. A behavior is considered stable when it is automatically executed without the need to expend excessive energy or effort in order to maintain it. Maintenance is not a static stage but a continuous process that lasts for about six months and may go for a longer time.

Relapse: Characterized by regression in behavior change with individuals going back and forth the stages. It is usually unexpected with individuals oscillating through the stages [31,34]. The focus of the intervention in this case should be to re-establish the plan, the reinforcement of self-efficacy and renewing of confidence [31]. A spiral shape is the preferable visual description of the transformation.

After relapse, the patient oscillates through each phase before consolidating the gains in behavior change, not changing but continuing to ascend the spiral [35].

This model is fluid in nature since behavior change is a process, with individuals shifting through abstinence and relapse. There is learning and personal growth before attaining stable abstinence. Based on the current specific stages, an individual’s readiness to change can be derived at any point in time (Figure 1).

There are inconsistencies in research findings that show a relationship of motivation to change to treatment outcome. Other research findings show treatment outcome as a prediction of the TTM and readiness to change upon starting treatment [36,37]. Conversely, behavior change is not related to motivation [38,39].

Substance use disorders

A substance use disorder is characterized by the inability to have voluntary control over substance use as well as health and social impairments [40]. Substance use disorders are in three levels of severity: mild, moderate, and severe [41].

SUDs are in two forms: Dependence (chronicity) and abuse or hazardous use. The symptoms range from increased tolerance for the substance, inability to abstain, replacement of healthy activities with substance use, and continued use despite medical or psychological problems which have been present for longer than 12 mths and are likely to persist if left untreated. Substance abuse is effective when people do not meet the dependence criteria reporting at least one moderately severe substance-related symptom putting them at high risk of developing dependence or harming themselves or others. Dependence requires treatment, while abuse results in referral to brief intervention or treatment [42].

Neuro-imaging studies have ascertained that a physiological basis underlies the clinical experience of SUD chronicity [43]. The findings have proved that cravings, cue reactivity, tolerance, and withdrawal can be seen in the brain; influencing brain development especially for adolescents; responding to medications as well as social and physical environment; and that chronic substance use is associated with physical changes in the brain that have an impact on brain functioning and emotional states [44-47].

Epidemiological data affirm that SUDs follow a chronic course; they emerge during adolescence and often progress in severity and complexity with continued substance misuse [48,49]. About 90 percent of individuals with dependence commence use of drugs before the age of 18, with half of them beginning before the age of 15.

Treatment of substance use disorders

Substance use disorders are treatable but challenged by increasing rates of relapse, readmissions, drop outs and mortality [12,14]. Somal and George [13] noted that most individuals with SUD access treatment during a crisis. The following factors were considered most important in a 30year systematic study of substance use disorders treatment.

• Readiness by an individual to commit to treatment

• Perceived and experienced social support

• An individual’s clinical profile

• An individual’s self-efficacy

• Treatment results and satisfaction

• An individual’s perception of life, its meaning and search for it

Pharmacological treatments

Pharmacological treatments are beneficial for selected patients with specific substance use disorders [50]. The categories of pharmacological treatments are:

1. Agonist maintenance therapies

2. Antagonist therapies

3. Abstinence-promoting and relapse prevention therapies

4. Drugs to treat intoxication and withdrawal states

5. Drugs to treat comorbid psychiatric conditions

6. Drugs to decrease the reinforcing effects of abused substances

Two main pharmaco-therapies are recommended for use among people with substance dependence: Methadone Maintenance Treatment (MMT) and buprenorphine [51]. Other forms of pharmacological treatment for substance dependence include naltrexone, Varenicline [52]. Of these, MMT is the most thoroughly studied and widely used treatment [53].

Psychosocial treatments

A comprehensive treatment program includes the psychosocial treatments as an essential component [50]. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments include cognitive-behavioral therapies (CBT), motivational enhancement therapy (MET), behavioral therapies (e.g., community reinforcement, contingency management), the 12-step facilitation (TSF), psychodynamic therapy/interpersonal therapy (IPT), self-help manuals, behavioral self-control, brief interventions, case management, and group, marital, and family therapies. There is evidence to support the efficacy of integrated treatment for patients with a co-occurring substance use and psychiatric disorder; such treatment includes blending psychosocial therapies used to treat specific substance use disorders with psychosocial treatment approaches for other psychiatric diagnoses (e.g. CBT for depression).

A study reported MET produced greater reductions in marijuana use over the 15-month follow-up. It was not more effective in a large scale study of alcoholics [54].

CBT reduces illicit drug use among individuals on a methadone maintenance program [55]. CBT and motivational interviewing also improves the adherence and efficacy of MMT [56]. Some studies have found it more effective [57] and others have reported outcomes equivalent to IT and TST [58,59].

The 12-step treatment (TST) contains limited published literature on efficacy. One study found TST to be more effective than clinical management for cocaine and alcohol [60].

In comparison, intensive inpatient programs are not more effective than weekly psychosocial treatment as an adjunct to MMT [56].

Motivational interviewing (MI) is client-centered targeting a person’s ambivalence to change. Adopting a counseling style, a counselor uses a conversational approach to help their client discover their interest in changing their substance using behavior. The objective is to examine and resolve ambivalence [61]. MI has been reported to produce lower rates of cocaine positive urines in relapse prevention after detoxification [62].

E-treatments

The treatment of substance use disorders is fast adopting electronic systems improving the quality and efficiency as well as reducing treatment gaps. It is cost effective and useful for remote areas. It based on technology as an add-on, substitute, and replacement for standard care. Technology-enhanced treatment interventions are mainly Webbased versions of evidence-based, in-person treatment components such as CBT and MET [63].

Research studies on the effectiveness of substance use disorder treatment approaches that incorporate Web and telephone-based technology. A study on the effect of daily self-monitoring calls in an interactive voice response technology system with personalized feedback compared it to standard motivational enhancement practice. Those who received the intervention decreased the number of drinks they had on the days they drink [64].

Treatment outcomes

A favorable treatment outcome is heavily dependent on completion of treatment [65]. Studies have explored the interaction of specific factors and treatment outcomes including readiness for therapy, selfefficacy [66,67] treatment outcome expectations and perceived social support [68] as directly linked to positive outcomes in treatment.

Studies have demonstrated that severe substance use often comprise a chronic condition marked by cycles of recovery, relapse and repeated treatments stretching many years before arriving at either a stable recovery, permanent disability or death [12]. Majority of people with lifetime substance dependence enter sustained recovery, though most have to take part in repeated treatment [14].

Longitudinal treatment studies have reported that most participants achieve stable recovery after 3 to 4 episodes of treatment over some years [14,15]. Dennis et al. [14] reported 27 years as the median time from first use to a year of abstinence while the median time from first treatment to a year of abstinence was 9 years with 3 to 4 treatment interludes.

Scott et al. studied the frequency and direction of transitions between points in the relapse, treatment re-entry, and recovery cycle over 2 years. About 33% moved from one point in the cycle to another each quarter; 82% transitioned at least once; and 62% transitioned multiple times [22].

There are impractical expectations that all patients entering addiction treatment have to maintain lifelong abstinence following a single episode of specialized treatment. However, most persons resume substance use after leaving treatment in the first year following treatment, mostly within the first 30-90 days ([15,22-24].

Positive outcomes

Abstinence and reduction of substance use: Abstinence depends heavily on treatment completion [11]. It can take a year of abstinence before an individual can be said to be in remission [69].

On average, individuals reach sustained abstinence after three to four episodes of different types of treatment over a couple of years [14,15,19,22,23].

A longitudinal study with 1,271 patients, 27 years was the estimated median time from first use to at least 1 drug-free year, and the median time from first treatment to 1 alcohol and drug-free year was 9 years with three to four sessions of treatment [14].

The length of time it takes an individual to reach at least 1 year of alcohol and drug abstinence is linked to the age of first substance use and the duration of use before starting treatment [22].

Another study by Scott et al., found the median time of use being significantly longer for people who started before age 15 than for those who started after age 20 [23]. In comparison, patients who commenced treatment within 10 years of their initial drug use achieved a year or more of abstinence after an average of 15 years, while those who entered treatment after 20 or more years of use achieved after an average of 35 or more years. These results show the need for early diagnosis and intervention ideally during the first decade of substance use.

Recovery: Recovery is the voluntarily sustained control over substance use, which maximizes health and wellbeing and participation in the rights, roles and responsibilities of society.

Most individuals with substance use disorders eventually enter sustained recovery, having no symptoms for a year; however, most do so after participating in multiple sessions of treatment [14]. Continuing care following discharge from an inpatient facility is associated with improved substance use outcomes [70].

A 12 year follow-up of persons treated for cocaine dependence found 52% in stable recovery [71] and a follow-up of clients treated for methamphetamine dependence showed a recovery rate similar to those of clients treated for heroin or cocaine dependence [72,73].

A review by Sheedy and Whitter indicated that on average 58% of individuals with chronic substance dependence attained sustained recovery with rates ranging from 30-72%. A later study by White et al. established an average recovery rate at 47.6% [74].

Individuals with higher substance use severity and environmental obstacles to recovery are not likely to transition from to recovery [22,75].

In another study, Scott et al. reported active participation in treatment as a primary correlate of the transition from use to recovery [23]. Among patients who started the year in recovery, the major predictor of whether patients maintained abstinence is not treatment, but their degree of self-help group participation.

Negative outcomes

Relapse: A relapse indicates that treatment needs to be reinstated or adjusted or that another treatment should be tried. Relapse rates for individuals with substance use disorders are similar to those of other chronic illnesses [21]. A large proportion of individuals who have been treated for substance use disorders are likely to relapse soon after treatment [76,77]. Relapse to substance abuse after treatment reaches 75% in the 3 to 6 month period following treatment [78].

In a ten year longitudinal study, about one-third of individuals in full remission relapsed in the first year, while two thirds relapsed within the follow-up period [77]. 71% of patients on outpatient treatment for marijuana dependence having achieved 2 weeks of continuous abstinence relapsed to marijuana use within 6 months [79]. Smyth et al. [80] reported 91% relapse rate; provision of a formal program of continuing care following discharge from a detoxification unit, results in low relapse rates [81].

Various causes for relapses have been cited such as depression, adverse life events, social pressure, stress, anxiety, positive mood, work stress, family dysfunction, marital conflict, and a low level of social support mostly cited [82,83]. Other factors include environmental cues, including the availability and accessibility to drugs and peer pressure, as part of the recovering individual’s environment [84,85].

Re-admission: Literature is inadequate on data for readmissions. Readmission rates are increasingly being used as an outcome measure in health services research and as a quality benchmark for health systems. Studies have reported that those completing treatment have significant low risks for readmissions. Females and those arrested in the year prior to treatment had increased risks of readmission, while males and those receiving a combination of inpatient and outpatient treatments had lower risks of readmission [86].

Beynon et al. [87] in the United Kingdom found that the trend towards shorter lengths of stay was associated with increasing rates of continued drug use at discharge and readmission within the year.

Drop outs from treatment interventions: Failure to complete treatment is often referred to as drop-out. Most patients drop out of treatment as compared to those that complete [65]. It has been identified as a major mental health services challenge [88].

Recent studies report drop-out rates ranging from 21.5-43% in detoxification [89,90] outpatient treatment 23-50% [91,92], inpatient treatment 17-57% [93] and substitution treatment 32-67.7% [94,95]. A meta-analysis of psychotherapy found a dropout rate between 19 and 47% [96]. A systematic review by Brorson et al. reported dropout rates from SUD treatment up to 90% [65].

The reasons for high dropout rates are poorly understood [97-100]. Ball et al. [101] and Palmer et al. [102] found that the most commonly reported reasons for drop-out were individual or personal factors rather than program related factors.

Previous studies have shown female gender as a significant predictor of drop-out, with only 39% (11/28) of women on treatment fully engaged compared to 74% (51/69) of the men [103-105]. The high odds of females failing to fully engage in treatment is as a result of several factors including history of trauma, stress and mood related factors [106,107].

High treatment drop outs has been associated with younger age and cognitive deficits [108-111]. Proactive engagement services result in individuals remaining engaged through the treatment process [112,113]. High drop-out rates come with a high cost to society in terms of increased prevalence, rise in crime and spread of HIV [4] and causing a great deal of pain to loved ones [65].

Mortality: Individuals with alcohol and substance use disorders seeking help have lower mortality rates compared to those that do not seek help [114]. Among age-matched populations high mortality rates of 1.6 to 4.7 greater have been reported among individuals as compared to those without the disorders [115]. Post-treatment deaths are associated with post-treatment relapse [116] and are products of poisoning and overdose, cancer, liver disease, suicide, cardiovascular disease, AIDS, or homicide [20].

Mortality rates are generally high for tobacco smokers [117], for those with co-occurring psychiatric illnesses [118] and for those who concurrently consume alcohol and/or other drugs following treatment [119].

Some studies indicate that those who enter treatment sooner and stay on treatment longer are at a lower risk of mortality [22,23,71]. Studies on mortality rates following discharge from methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) reported an 8% death rate within one year of discharge from MMT in the first study [120] and a 5% death rate at six months following MMT in the second study [121]. The increased mortality rate following cessation of opiate detoxification and drug-free treatment is linked directly to the loss of drug tolerance [122].

Conclusion

There is a general lack of comprehensive data on outcomes of treatment and rehabilitation services for SUDs. Most research in this area has largely applied observational approaches. Studies shy away from interventional studies which give more practical and evidence based findings.

Most important is the need to study available and effective intervention strategies for treating substance use disorders. Continued research into effective and feasible treatment options and interventions is therefore important to inform on how to bridge the treatmentoutcome gap.

References

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2008) Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health: Commission on social determinants of health final report. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Degenhardt L, Whiteford H, Hall W, Vos T (2009) Estimating the burden of disease attributable to illicit drug use and mental disorders: what is ‘Global burden of disease 2005’ and why does it matter? Addiction 104: 1466-1471.

- Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD (2012) A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: A systematic analysis for the Global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet 380: 2224-2260.

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, UNODC (2012) World Drug Report 2012.

- Myers B, Louw J, Fakier N (2008) Alcohol and drug abuse: Removing structural barriers to treatment for historically disadvantaged communities in Cape Town. Int J Soc Welf 17: 156-165.

- Pasche S, Kleintjes S, Wilson D, Stein DJ, Myers B (2015) Improving addiction care in South Africa: Development and challenges to implementing training in addictions care at the University of Cape Town. Int J Ment Health Ad 13: 322-332.

- Saxena S (2006) Conclusion In: Disease control priorities related to mental, neurological, developmental and substance abuse disorders 10. Geneva: World Health Organization, pp: 101-103.

- Degenhardt L, Bucello C, Calabria B (2011) What data are available on the extent of illicit drug use and dependence globally? Results of four systematic reviews. Drug Alcohol Depend 117: 85-101.

- United Nations office on drugs and crime, UNODC (2016) World Drug Report 2016.

- Walker MA (2009) Program characteristics and the length of time clients are in substance abuse treatment. J Behav Health Serv Res 36: 330-343.

- Kleber HD, Weiss RD, Anton RF Jr, George TP, Greenfield SF, et al. (2007) Treatment of patients with substance use disorders, second edition. American Psychiatric Association. Am J Psychiatry 164: 5-123.

- Dennis M, Scott CK (2007) Managing addiction as a chronic condition. Addict Sci Clin Pract 4: 45-55.

- Somal K, George T (2013) Referral strategies for patients with co-occurring substance use and psychiatric disorders. Psychiatric Times.

- Dennis ML, Scott CK, Funk R, Foss MA (2005) The duration and correlates of addiction and treatment careers. J Subst Abuse Treat 28: S51-S62.

- Hser YI, Grella CE, Chou CP, Anglin MD (1998) Relationships between drug treatment careers and outcomes: Findings from the National drug abuse treatment outcome study. Eval Rev 22: 496-519.

- Anglin MD (2001) Drug treatment careers: Conceptual overview and clinical, research, and policy applications. In: Tims F, Leukefeld C, Platt J, editors. Relapse and recovery in addictions. New Haven, Yale University press, pp: 18-39.

- Anglin MD, Hser YI, Grella CE (1997) Drug addiction and treatment careers among clients in the drug abuse treatment outcome study (DATOS). Psychol Addict Behav 11: 308-323.

- Dennis ML, Scott CK, Funk R (2003) An experimental evaluation of recovery management checkups (RMC) for people with chronic substance use disorders. Eval Program Plann 26: 339-352.

- Hser YI, Anglin C, Grella D, Longshore, Prendergast ML (1997) Drug treatment careers: A conceptual framework and existing research findings. J Subst Abuse Treat 14: 543-58.

- Hser, YI, Evans E, Huang D and Anglin, MD (2001) Relationship between drug treatment services, retention and outcomes. Psychiatr Serv 55: 767.

- McLellan AT, Lewis DC, O’Brien CP, Kleber HD (2000) Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: Implications for treatment, insurance and outcomes evaluation. JAMA 284: 1689-1695.

- Scott CK, Foss MA, Dennis ML (2005) Pathways in the relapse-treatment-recovery cycle over 3 years. J Subst Abuse Treat 28 Suppl 1: S63-72.

- Scott CK, Foss MA, Dennis ML (2005) Utilizing recovery management checkups to shorten the cycle of relapse, treatment re-entry and recovery. Drug Alcohol Depend 78: 325-338.

- Simpson DD, Joe GW, Broome KM (2002) A national 5 year follow-up of treatment outcomes for cocaine dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry 59: 538-544.

- Weisner C (2004) Report of the blue ribbon task force on health services research at the National institute on drug abuse. Rockville, MD: National institute on drug abuse.

- White WL (1996) Pathways from the culture of addiction to the culture of recovery: A travel guide for addiction professionals. Center City, MN: Hazelden.

- Saxena S, Thornicroft G, Knapp M, Whiteford H (2007) Resources for mental health: Scarcity, inequity, and inefficiency. Lancet 370: 878-889.

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC (1983) Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: toward an integrative model of change. J Consult Clin Psychol 51: 390-395.

- Migneault JP (2005) Application of the trans-theoretical model to substance abuse: Historical development and future directions. Drug Alcohol Rev 24: 437-448.

- Callaghan RC (2005) Does stage of change predict dropout in culturally diverse sample of adolescents admitted to inpatient substance abuse treatment? A test of the trans-theoretical model. Addict Behav 30: 1834-1847.

- DiClemente CC (2006) Addiction and change: How addictions develop and addicted people recover. New York: Guilford Press.

- DiClemente CC, Schlundt D, Gemmell L (2004) Readiness and stages of change in addiction treatment. Am J Addict 13: 103-119.

- Littell JH, Girvin H (2002) Stages of change. A critique. Behav Modif 26: 223-273.

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Norcross JC (1992) In search of how people change. Applications to addictive behaviors. Am Psychol 47: 1102-1114.

- DiClemente CC (1991) The process of smoking cessation: An analysis of pre-contemplation, contemplation, and preparation stages of change. J Consult Clin Psychol 59: 295-304.

- Demmel R, Beck B, Richter D, Reker T (2004) Readiness to change in a clinical sample of problem drinkers: relation to alcohol use, self-efficacy, and treatment outcome. Eur Addict Res 10: 133-138.

- Freyer-Adam J, Coder B, Ottersbach C, Tonigan JS, Rumpf HJ, et al. (2009) The performance of two motivation measures and outcome after alcohol detoxification. Alcohol Alcohol 44: 77-83.

- Field CA, Adinoff B, Harris TR, Ball SA, Carroll KM (2009) Construct concurrent and predictive validity of the URICA: Data from two multi-site clinical trials. Drug Alcohol Depend 101: 115-123.

- Borsari B, Murphy JG, Carey KB (2009) Readiness to change in brief motivational interventions: A requisite condition for drinking reductions? Addict Behav 34: 232-235.

- Medina KL, Shear PK, Corcoran K (2005) Ecstasy (MDMA) exposure and neuropsychological functioning: A polydrug perspective. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 11: 1-13.

- Medina J (2015) Symptoms of substance use disorders (Revised for DSM-5).

- American psychiatric association (2000) Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder (revision). Am J Psychiatry 157: 1-45.

- Fowler JS, Volkow ND, Kassed CA, Chang L (2007) Imaging the addicted human brain. Sci Pract Perspect 3: 4-16.

- Kufahl PR (2005) Neural responses to acute cocaine administration in the human brain detected by fMRI. Neuroimage 28: 904-914.

- Paulus MP, Tapert SF, Schuckit MA (2005) Neural activation patterns of methamphetamine dependent subjects during decision making predict relapse. Arch Gen Psychiatry 62: 761-768.

- Risinger RC, Salmeron BJ, Ross TJ, Amen SL, Sanfilipo M, et al. (2005) Neural correlates of high and craving during cocaine self-administration using BOLD fMRI. Neuroimage 26: 1097-1108.

- Schlaepfer TE (2006) Decreased frontal white matter volume in chronic substance abuse. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 9: 147-153.

- Compton WM, Thomas, YF, Stinson FS, Grant, BF (2007) Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV drug abuse and dependence in the United States: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry 64: 566-576.

- Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Ogburn E, Grant BF (2007) Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States: Results from the National epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry 64: 830-842.

- Wutzke SE, Conigrave KM, Saunders JB, Hall WD (2002) The long-term effectiveness of brief interventions for unsafe alcohol consumption: A 10 year follow-up. Addiction 97: 665-675.

- Ritter AJ (2002) Naltrexone in the treatment of heroin dependence: Relationship with depression and risk of overdose. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 36: 224-228.

- Coe JW (2005) Varenicline: An alpha4beta2 nicotinic receptor partial agonist for smoking cessation. J Med Chem 48: 3474-3477.

- Mattick RP (2003) Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2: CD002207

- UK alcohol treatment trial (UKATT) Research Team (2005) Effectiveness of treatment for alcohol problems: Findings of the randomized UK alcohol treatment trial (UKATT). BMJ 331: 541-547.

- Teesson M (2000) Alcohol and drug-use disorders in Australia: Implications of the National survey of mental health and wellbeing. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 34: 206-213.

- Goving L (2001) Evidence supporting treatment: The effectiveness of interventions for illicit drug use. Australian National Council on Drugs: Woden, ACT.

- Balldin J, Berglund M, Borge S, Mansson M, Bendtsen P, et al. (2003) A 6 month controlled naltrexone study: Combined effect with cognitive behavioral therapy in outpatient treatment of alcohol dependence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 27: 1142-1149.

- McKay JR, Lynch KG, Shepard DS, Ratichek S, Morrison R, et al. (2004) The effectiveness of telephone based continuing care in the clinical management of alcohol and cocaine use disorders: 12 month outcomes. J Consult Clin Psychol 72: 967-79.

- McKay JR, Foltz C, Leahy P, Stephens R, Orwin RG, et al. (2004) Step down continuing care in the treatment of substance abuse: Correlates of participation and outcome effects. Eval Program Plann 27: 321-331.

- Carroll KM, Nich C, Ball SA, McCance E, Rounsavile BJ (1998) Treatment of cocaine and alcohol dependence with psychotherapy and disulfiram. Addiction 93: 713-727.

- Miller WR, Rollnick S (2011) Motivational interviewing: Helping people change. New York, Guilford Press.

- Stotts AL, Schmitz JM, Rhoades HM, Grabowski HG (2001) Motivational interviewing with cocaine-dependent patients: A pilot study. J Consult Clin Psychol 69: 858-862.

- Rosa C, Campbell AN, Miele GM, Brunner M, Winstanley EL (2015) Using e-technologies in clinical trials. Contemp Clin Trials 45: 41-54.

- Hasin DS, Aharonovich E, O’Leary A, Greenstein E, Pavlicova M, et al. (2013) Reducing heavy drinking in HIV primary care: A randomized trial of brief intervention, with and without technological enhancement. Addiction 108: 1230-1240.

- Brorson HH, Arnevik EA, Rand-Hendriksen K, Duckert F (2013) Drop-out from addiction treatment: A systematic review of risk factors. Clin Psychol Rev 33: 1010-1024.

- Kadden, RM, Litt MD (2011) The role of self efficacy in the treatment of substance use disorders. Addict Behav 36: 1120-1126.

- Burleson JA, Kaminer Y (2005) Self-efficacy as a predictor of treatment outcome in adolescent substance use disorders. Addict Behav 30: 1751-1764.

- Ellis B, Bernichon T, Yu Ping, Roberts T, Herrell JM (2004) Effect of social support on substance abuse relapse in a residential treatment setting for women. Eval Program Plann 27: 213-221.

- American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

- American psychiatric association (2006) Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with substance use disorders. Am J Psychiatry 163: S1-S82.

- Hser YI, Stark ME, Paredes A, Huang D, Anglin MD, et al. (2006) A 12-year follow-up of a treated cocaine dependent sample. J Subst Abuse Treat 30: 219-226.

- Callaghan R, Taylor L, Victor JC, Lentz T (2007) A case-matched comparison of readmission patterns between primary methamphetamine-using and primary cocaine-using adolescents engaged in inpatient substance-abuse treatment. Addict Behav 32: 3101-3106.

- Luchansky B, Krupski A, Stark K (2007) Treatment response by primary drug of abuse: Does methamphetamine make a difference? J Subst Abuse Treat 232: 89-96.

- White WL (2012) Recovery/remission from substance use disorders: An analysis of reported outcomes in 415 scientific reports, 1868-2011. Philadelphia, PA: Philadelphia Department of behavioral health and intellectual disability services.

- White W (2009) Long term strategies to reduce the stigma attached to addiction, treatment and recovery within the city of Philadelphia (with particular reference to medication-assisted treatment and recovery). Philadelphia: Department of behavioral health and mental retardation services.

- Walton MA, Blow FC, Bingham CR, Chermack ST (2003) Individual and social environmental predictors of alcohol and drug use 2 years following substance abuse treatment. Addict Behav 28: 627-642.

- Xie H, McHugo GJ, Fox MB, Drake RE (2005) Substance abuse relapse in a ten-year prospective follow-up of clients with mental and substance use disorders. Psychiatr Serv 56: 1282-1287.

- Adinoff B, Talmadge C, Williams MJ, Schreffler E, Jackley PK, et al. (2010) Time to relapse questionnaire (TRQ): A measure of sudden relapse in substance dependence. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 36: 140-149.

- Moore D, Guthmann D, Roger N, Fraker S, Embree J (2009) E-therapy as a means for addressing barriers to substance use disorder treatment for persons who are deaf. J Sociol Soc Welf 36: 75-92.

- Smyth BP, Barry J, Keenan E, Ducray K (2010) Lapse and relapse following inpatient treatment of opiate dependence. Ir Med J 103: 176-179.

- Marsh A (2006) Addiction counselling: Content and process. Melbourne: IP Communications.

- Sinha R (2001) How does stress increase risk of drug abuse and relapse? Psychopharmacology (Berl) 158: 343-359.

- Mattoo SK, Chakrabarti S, Anjaiah M (2009) Psychosocial factors associated with relapse in men with alcohol or opioid dependence. Indian J Med Res 130: 702-708.

- Barone SH, Roy CL, Frederickson KC (2011) Instruments used in Roy adaptation model-based research: Review, critique, and future directions. Nurs Sci Q 21: 353-362.

- Wadhwa S (2009) Relapse. In: Fisher, G.L. and Roget, N.A. Encyclopedia of substance abuse prevention, treatment and recovery 2: 772-778.

- Luchansky B (2000) Predicting readmission to substance abuse treatment using state information systems: The impact of client and treatment characteristics. J Subst Abuse 12: 255-270.

- Beynon CM, Bellis MA, McVeigh J (2006) Trends in drop-out, drug free discharge and rates of representation: A retrospective cohort study of drug treatment clients in the North West of England. BMC Public Health 6: 205.

- Simon GE, Imel ZE, Ludman EJ (2012) Is dropout after a first psychotherapy visit always a bad outcome? Psychiatr Serv 63: 705-707.

- Gilchrist G, Langohr K, Fonsecal F, Muga R, Torrens M (2012) Factors associated with discharge against medical advice from an alcohol and drug inpatient detoxification unit in Barcelona between 1993 and 2006. Heroin Addict Relat Clin Probl 14: 35-44.

- Specka M, Buchholz A, Kuhlmann, T, Rist F, Scherbaum N (2011) Prediction of the outcome of inpatient opiate detoxification treatment: Results from a multicentre study. Eur Addict Res 17: 178- 184.

- McHugh RK, Whitton SW, Peckham AD, Welge JA, Otto MW (2013) Patient preference for psychological vs pharmacologic treatment of psychiatric disorders: A meta-analytic review. J Clin Psychiatry 74: 595-602.

- Gómez FJS, Hervás ES, Villa RS, Romaguera FZ, RodrÃguez OG, et al. (2010) Pretreatment characteristics as predictors of retention in cocaine dependent outpatients. Addict Disord Their Treat 9: 93-98.

- Deane FP, Wootton DJ, Hsu Ching-I, Kelly PJ (2012) Predicting dropout in the first 3 months of 12-step residential drug and alcohol treatment in an Australian sample. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 73: 216-225.

- Lin HC, Chen KY, Wang PW, Yen CF, Wu HC, et al. (2013) Predictors for dropping-out from methadone maintenance therapy programs among heroin users in southern Taiwan. Subst Use Misuse 48: 181-191.

- Smyth BP, Fagan J, Kernan K (2012) Outcome of heroin-dependent adolescents presenting for opiate substitution treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat 42: 35-44.

- Swift JK, Greenberg RP (2012) Premature discontinuation in adult psychotherapy: A meta-analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol 80: 547-559.

- Braune NJ, Schroder J, Gruschka P, Daecke K, Pantel J (2008) Determinants of unplanned discharge from in-patient drug and alcohol detoxification: A retrospective analysis of 239 admissions. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr 76: 217-224.

- Callaghan RC, Cunningham JA (2002) Gender differences in detoxification: Predictors of completion and re-admission. J Subst Abuse Treat 23: 399-407.

- Martinez-Raga J, Marshall EJ, Keaney F, Ball D, Strang J (2002) Unplanned versus planned discharges from in-patient alcohol detoxification: Retrospective analysis of 470 first-episode admissions. Alcohol Alcohol 37: 277-281.

- Reker T, Richter D, Batz B, Luedtke U, Koritsch HD, et al. (2004) Short-term effects of acute inpatient treatment of alcoholics. A prospective, multicenter evaluation study. Der Nervenarzt 75: 234-241.

- Ball SA, Carroll KM, Canning-Ball M, Rounsaville BJ (2006) Reasons for dropout from drug abuse treatment: Symptoms, personality and motivation. Addict Behav 31: 320-330.

- Palmer RS, Murphy KM, Piselli, Ball SA (2009) Substance abuse treatment drop-out from client and clinician perspectives. Subst Use Misuse 44: 1021-1038.

- Arfken CL, Klein C, di Menza S, Schuster CR (2001) Gender differences in problem severity at assessment and treatment retention. J Subst Abuse Treat 20: 53-57.

- McCaul ME, Svikis DS, Moore RD (2001) Predictors of outpatient treatment retention: Patient versus substance use characteristics. Drug Alcohol Depend 62: 9-17.

- King AC, Canada SA (2004) Client-related predictors of early treatment drop-out in a substance abuse clinic exclusively employing individual therapy. J Subst Abuse Treat 26: 189-195.

- Miller BA, Wilsnack SC, Cunradi CB (2000) Family violence and victimization: Treatment issues for women with alcohol problems. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 24: 1287-1297.

- King, AC, Bernardy, NC, Hauner, K (2003) Stressful events, personality, and mood disturbance: Gender differences in alcoholics and problem drinkers. Addict Behav 28: 171-187.

- Aharonovich E, Amrhein, PC, Bisaga A, Nunes EV, Hasin DS (2008) Cognition, commitment language, and behavioral change among cocaine-dependent patients. Psychol Addict Behav 22: 557-562.

- Thompson-schill SL, Ramscar M, Chrysikou EG (2009) Cognition without control when a little frontal lobe goes a long way. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 18: 259-263.

- Romer D (2010) Adolescent risk taking, impulsivity and brain development: Implications for prevention. Dev Psychobiol 52: 263-276.

- Stevens L, Verdejo-GarcÃa A, Goudriaan AE, Roeyers H, Dom G, et al. (2014) Impulsivity as a vulnerability factor for poor addiction treatment outcomes: A review of neuro-cognitive findings among individuals with substance use disorders. J Subst Abuse Treat 47: 58-72.

- Messina N, Grella CE, Cartier J, Torres S (2010) A randomized experimental study of gender-responsive substance abuse treatment for women in prison. J Subst Abuse Treat 38: 97-107.

- Prendergast ML, Messina NP, Hall EA, Warda US (2011) The relative effectiveness of women-only and mixed-gender treatment for substance-abusing women. J Subst Abuse Treat 40: 336-348.

- Timko C, DeBenedetti A, Moos BS, Moos RH (2006) Predictors of 16-year mortality among individuals initiating help-seeking for an alcoholic use disorder. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 30: 1711-1720.

- Degenhardt L, Randell D, Hall W, Law M, Butler T, et al. (2009) Mortality among clients of a state-wide opioid pharmacotherapy program over 20 years: Risk factors and lives saved. Drug Alcohol Depend 105: 9-15.

- Mann K, Schäfer DR, Längle G, Ackermann K, Croissant B (2005) The long-term course of alcoholism 5, 10 and 16 years after treatment. Addiction 100: 797-805.

- Vaillant GE (1996) A long-term follow-up of male alcohol abuse. Arch Gen Psychiatry 53: 243-249.

- Fridell M, Hesse M (2006) Psychiatric severity and mortality in substance abusers: A 15-year follow-up of drug users. Addict Behav 31: 559-565.

- Gossop M, Stewart D, Treacy S, Marsden J (2002) A prospective study of mortality among drug misusers during a 4 year period after seeking treatment. Addiction 97: 39-47.

- Zanis DA, Woody GE (1998) One-year mortality rates following methadone treatment discharge. Drug Alcohol Depend 52: 257-260.

- Coviello DM, Zanis, DA, Wesnoski SA, Alterman AI (2006) The effectiveness of outreach case management in re-enrolling discharged methadone patients. Drug Alcohol Depend 85: 56- 65.

- Strang J, McCambridge J, Best D, Beswick T, Bearn J, et al. (2003) Loss of tolerance and overdose mortality after inpatient opiate detoxification: Follow up study. BMJ 26: 959-960.

Citation: Njoroge MW (2017) Review on Treatment of Substance Use Disorders. J Addict Res Ther 8: 353. DOI: 10.4172/2155-6105.1000353

Copyright: © 2017 Njoroge MW. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 9724

- [From(publication date): 0-2018 - Dec 06, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 8575

- PDF downloads: 1149