Research Article Open Access

Uterine Cavity Assessment and Endometrial Hormonal Receptors in Women with Peri and Post Menopausal Bleeding

Ahmed M Maged*, Ahmed L Aboul Nasr, Mostafa A Selem, Sherine H Gad Allah and Ahmed A Wali

Obstetrics and Gynecology Department, Kasr Aini Hospital, Cairo University, Egypt

- *Corresponding Author:

- Ahmed Mohamed Maged

135 King Faisal Street Haram Giza, Egypt

Tel: 0105227404

E-mail: prof.ahmedmaged@gmail.com

Received date: February 15, 2016; Accepted date: June 07, 2016; Published date: June 11, 2016

Citation: Maged AM, Nasr ALA, Selem MA, Allah SHG, Wali AA (2016) Uterine Cavity Assessment and Endometrial Hormonal Receptors in Women with Peri and Post Menopausal Bleeding. Trends Gynecol Oncol 1:105. doi:10.4172/ctgo.1000105

Copyright: © 2016 Maged AM, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Insights in Gynecologic Oncology

Abstract

Objectives: To compare the accuracy of 2D-Transvagfinal ultrasound (TVUS), saline infused sonohysterography (SIS) and hysteroscopy (DH) in assessment of the uterine cavity in women with peri- and postmenopausal bleeding and to study the expression of endometrial estrogen receptors (ER) and progesterone receptors (PR) in them. Study design: 100 women with abnormal uterine bleeding (peri and postmenopausal) were subjected to TVUS, SIS and DH and fractional curettage followed by histopathological examination and immunohistochemical analysis for ER and PR. Results: Measurement of endometrial thickness by TVUS showed a significant difference between normal and atrophic endometrium and between atrophic endometrium and endometrial polyp (P value 0.004 and 0.001 respectively) DH had the best sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV as a diagnostic procedure followed by SIS then TVUS (97.7, 100,100,99.4 % vs. 74,91.2,67.3,93.5 and 52.9,89.4,56.3, 88.1 respectively) Both ER and PR scoring among glands and stroma showed a significant difference between normal and abnormal endometrium. ER expression in glands showed a significant difference between endometrial polyp and surrounding endometrium (P value 0.006) Conclusions: Sonohysterography is superior to ultrasound and very close to hysteroscopy, especially with intra-cavitary lesions. Hysteroscopy remains the gold standard for uterine cavity assessment, but cannot replace the histopathology. The expression of endometrial steroid receptors is important in the pathogenesis of endometrial polyps and endometrial hyperplasia.

Keywords

Perimenopausal bleeding; Postmenopausal bleeding; Transvaginal ultrasound; Sonohysterography; Hysteroscopy; Estrogen receptors; Progesterone receptors; Endometrial polyp

Introduction

Abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) is the cause of many gynecological visits in pre and postmenopausal and can be due to the presence of either benign conditions or the presence of endometrial cancer [1]. Dilatation and curettage (D&C) is the currently accepted method for diagnosing diffused endometrial conditions as endometrial cancer and hyperplasia. However, when focal endometrial conditions (as endometrial polyps and eiomyomas) or myometrial conditions (such as adenomyosis) are present, D&C is not capable of diagnosing them [2].

Transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) is a method routinely used for differentiating between the causes of AUB. However, in TVUS images it is difficult to distinguish between a thickened endometrial lining and other diffuse or focal endometrial abnormalities [3]. An improved TVUS method is saline infused sonohysterography (SIS) which allows uterine abnormalities to be seen more clearly by pushing apart the walls of the uterine cavity with saline infused into the cavity [4]. Hysteroscopy (DH) with biopsy has become the gold standard for evaluation of the uterine cavity, as a reliable and safe method in routine outpatient settings [5].

Studying the immunohistochemical reactivity of the postmenopausal endometrium using monoclonal antibodies against ERs (estrogen receptors) and PRs (progesterone receptors) showed thicker endometrium in menopausal women for 1 to 10 years than in those who were menopausal for more than 10 years. Within the glands +ve ER was found in 26/33 and +ve PR was found in 18/33 of cases [6].

Endometrial polyps (EP) are a frequent cause of AUB, but their pathogenesis is poorly understood. EP may result from a decrease in ER and PR expression in stromal cells [7]. The aim of this study is to compare the accuracy of both 2D TVUS and SIS in relation to DH in assessment of uterine cavity and to detect ER and PR in endometrium and their association with endometrial polyps in women with peri and postmenopausal bleeding.

Material and Methods

The present prospective study included 100 patients with AUB who attended the outpatient gynecology clinic at Kasr El-Aini Hospital in Cairo, Egypt, between June 1, 2011, and October 31, 2014. The study was approved by the local Ethics Committee and informed consents about the study and expected value and outcome were obtained from all participants.

The 100 women included in our study were older than 45 years with AUB for more than 3 months duration. Of these women 50 had postmenopausal bleeding, 10 had premenopausal menorrhagia, 4 had premenopausal metrorrhagia and 36 had premenopausal menometrorrhagia Exclusion criteria included history of hormonal treatment or hormonal contraception within the last 6 months. Women who had used IUD or those had hystroscopy or fractional curettage done within the last 6 months were also excluded.

All the patients were subjected to Full history, clinical examination including general, abdominal and pelvic examination and Laboratory investigations as complete blood count, coagulation profile, fasting and post-prandial blood sugar, liver and kidney functions and pregnancy test (for the premenopausal women).

Conventional TVUS was done to all participants to measure the uterine size and endometrial thickness and other pathology. TVUS was done with an empty bladder in the lithotomy position using the Sonoace-X6 (Medison Co. Ltd., Korea) ultrasound machine, with an endovaginal curved linear probe (EV 4-9/10 ED) with frequency 4-9 MHz. SIS was performed for all patients at the same setting of TVUS. With the patient in the lithotomy position, a speculum was inserted into the vaginal introitus. The cervical os was localized and cleaned with a povidone-iodine solution. A 6 or 8 French Foley’s catheter was inserted through the external cervical os into the cervical canal. Its balloon tip was inflated with 2-3 mL of saline, depending on patient comfort, to help hold it in place. The speculum was then removed.

The vaginal probe was then reinserted and a 5-10 mL syringe filled with sterile saline was attached to the catheter. Fluid was instilled while the transducer was moved from side to side (cornua to cornua) in a long-axis projection then the transducer was rotated 90° into an axial plane. More fluid was instilled while fanning down toward the endocervical canal and up toward the uterine fundus to obtain a detailed survey of the endometrium. Every portion of the uterine cavity should be imaged, to exclude any focal abnormality as polyps, myomas, hyperplasia, and carcinoma. Any detected intrauterine pathology is described; including its shape, size and site.

The hysteroscope used in this study was Karl Storz (Germany). It is a rigid continuous flow panoramic hysteroscope, 25 cm in length, 4 mm in diameter with an outer sheath 5 mm diameter and 30° fibrooptic lens. The light source used in this study was a metal halide automatic light source from Circon ACMI G71A (Germany) with a 150 Watt lamp, connected to the hysteroscope through a fibro-optic cable.

The technique used to provide constant uterine distention was by attaching plastic bags of saline. Infusion pressure was elevated by pneumatic cuff under manometric control at a pressure of 100-120 mmHg. The procedure was monitored using a single chip video and the image is displayed on a monitor visible to the operator. The camera was Karl Storz (Germany) with a focal length varying from f 70 to f 140.

Detailed hysteroscopic examination was performed under general anesthesia with the patient in the lithotomy position, cleaning the area around the vulva, vagina and the cervix with a nonfoaming aseptic solution, Emptying the bladder by a metal catheter, Bimanual examination, Introduction of a vaginal retractor into the vagina to expose the cervix and a multiple toothed volsellum was applied to the anterior lip of the cervix, The endocervical canal was curetted before introduction of the telescope, Dilatation of the cervix was needed –in some cases– up to Hegar no. 6; but it was better to be avoided as the tight cervical os avoids loss of the distending medium, The telescope was introduced through the external cervical os under direct vision, Once the cavity was entered, a panoramic view of the uterine cavity then systematic; first the fundus, then anterior, posterior and lateral walls of the uterus consecutively, ending by visualization of the utero-tubal junctions, The thickness, colour, aspect and vasculature of the mucous membrane lining the uterine cavity was observed and recorded. If there was any intrauterine pathology detected; the shape, size and site were estimated. If an endometrial polyp was found it was removed using a ring forceps. At the end of the procedure, the hysteroscope was slowly withdrawn through the cervical canal to visualize it.

Endometrial curettage was done to all patients, and specimens were fixed in Formalin 10% solution for histopathological examination. Patients in whom endometrial polyps were found by hysteroscopy, had polypectomy performed before curettage. The first sample was taken from the endocervical canal before hysteroscopy or cervical dilatation. Following diagnostic hysteroscopy, cervical dilatation up to Hegar no. 7 or 8 was done. A sharp curette was introduced into the uterine cavity, and curettage was done starting with the fundus then posterior, anterior, right and left lateral walls consecutively.

Histopathological examination, all curettage and polypectomy specimens were embedded in paraffin wax, then slides were prepared to be stained by the conventional Haematoxylin and Eosin (H & E) stain.

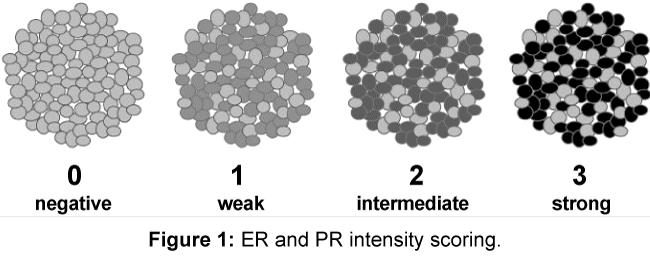

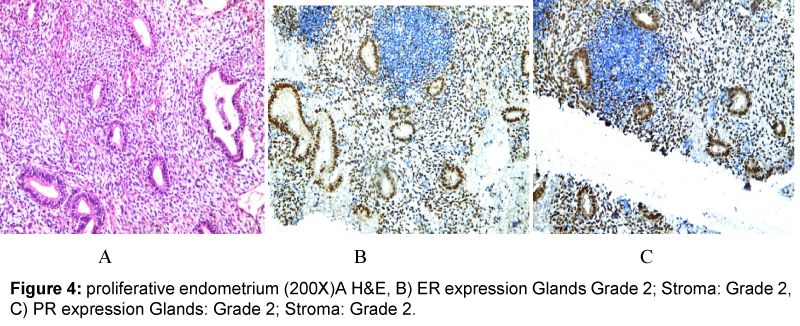

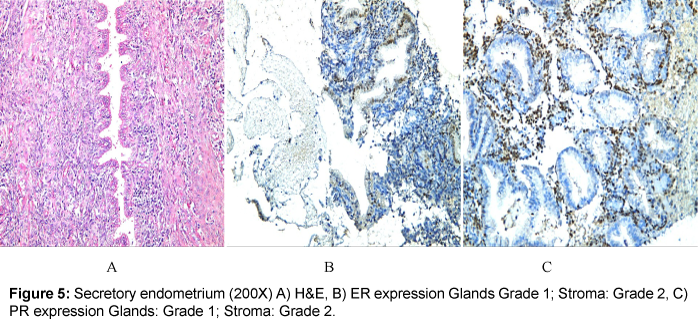

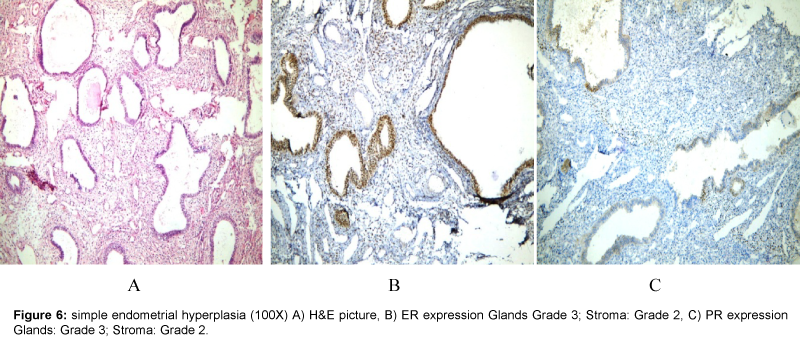

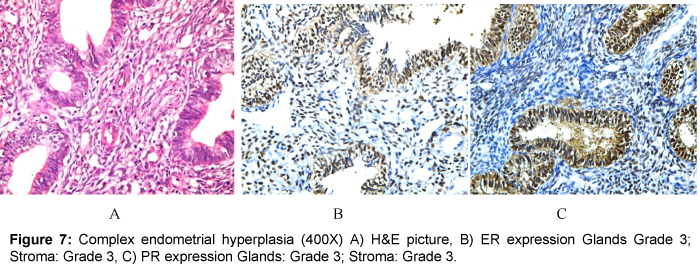

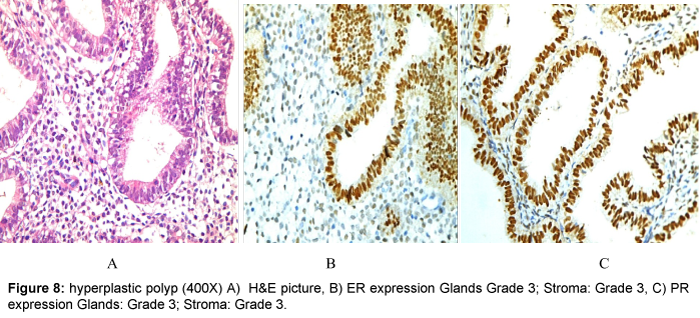

Detection of estrogen and progesterone receptors in the specimens (formalin-fixed, paraffin wax-embedded) using immunohistochemical staining which was carried out by using the Dako ER/PR pharmDx™ Kit which specifically detects the ERα protein as well as the PR-A protein located in the cell nuclei of ER and PR expressing cells, respectively. An intensity score is assigned according to the estimated average staining intensity of ER or PR positive cells, as follows: Grade 0 negative, Grade 1 weak, Grade 2 intermediate and Grade 3 strong (Figure 1).

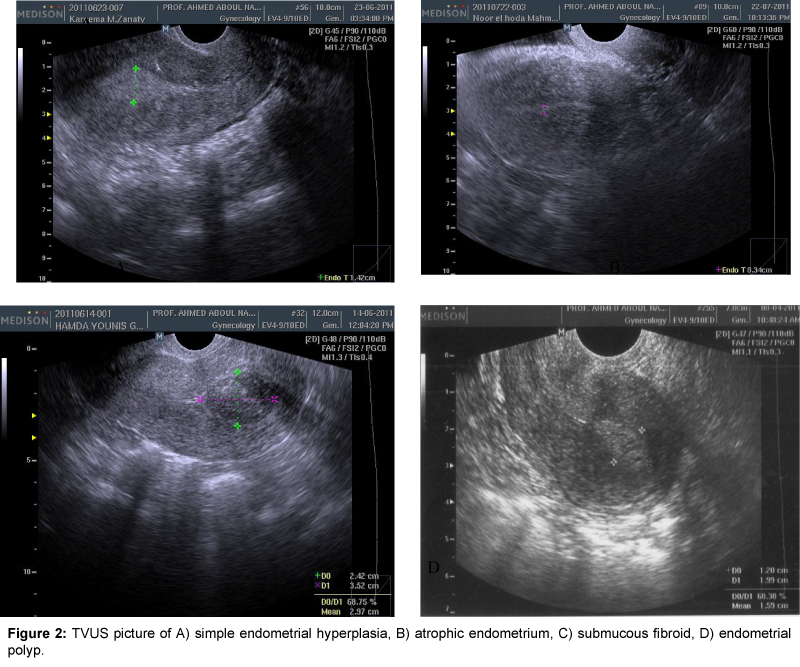

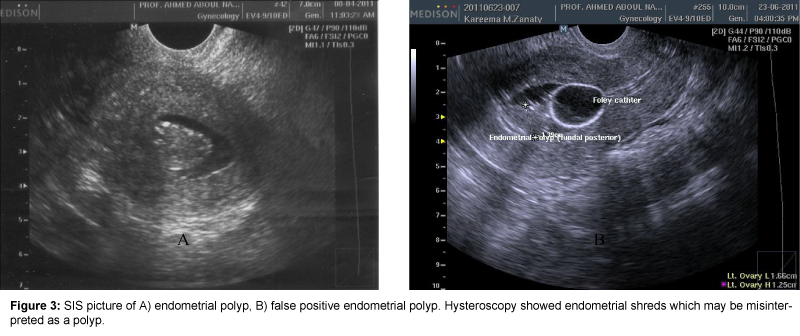

Data was statistically represented in terms of mean, standard deviation and percentages. Comparison was done using Two-tail Student t test for parametric data. For comparing non-parametric data, Chi-Square (x2) test was performed. A probability value (P value) less than 0.05 was considered significant (Figures 2-8).

All statistical calculations were done using computer programs Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, NY, USA) and SPSS (Statistical package for the social science) statistical programs (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

The main characteristics of the study group including age, parity and diagnosis of lesion were shown in Table 1. There was no relation between either age or parity to diagnosis (Table 1). TVUS could detect all cases with submucus myoma (SMF), half of cases with endometrial polyps and endometrial atrophy, only 2/16 of women with normal endometrium and over diagnosis of endometrial hyperplasia (Table 2). SIS could detect all cases with SMF, most cases with endometrial polyp and endometrial hyperplasia, 10/16 of cases with endometrial atrophy and normal endometrium (Table 2).

| Age (50.52± 6.31) | Parity (5.20± 2.59) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number and percentage | Mean ± SD | P value | Mean ± SD | P value | |

| Endometrial polyp | 32 | 51.44 ± 6.84 | 0.35 NS |

5.31 ± 2.11 | 0.295 NS |

| Endometrial hyperplasia | 22 | 52.09 ± 8.30 | 5.73 ± 2.26 | ||

| Endometrial atrophy | 16 | 51.88 ± 5.21 | 4.25 ± 2.59 | ||

| Normal endometrium (DUB) | 16 | 48.25 ± 2.39 | 6.38 ± 3.71 | ||

| Submucous fibroid | 14 | 47.00 ± 2.45 | 3.86 ± 1.25 | ||

Table 1: Relation of age and parity to different diagnoses.

| TVUS | SIS | DH | Diagnosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endometrial polyp | 16 | 32(1) | 32 | 32 |

| Endometrial hyperplasia | 24 | 18(2) | 16 | 18 |

| Endometrial atrophy | 8 | 10 | 16 | 16 |

| Normal endometrium | 2 | 10 | 16 | 16 |

| Submucous fibroid | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 |

(1) With endometrial polyps, SIS had 2 false negative result by missing one case, and 2 false positive result by diagnosing a case of 2 endometrial hyperplasia as polypi.

(2) With hyperplasia, SIS had 6 false negative results (by missing 6 cases), and 6 false positive results (2 cases was found to have polypi and 4 cases were normal).

Table 2: Comparison of diagnoses using different uterine assessment modalities with the actual diagnosis.

DH could detect all cases with endometrial polyp, endometrial atrophy, normal endometrium and 16/18 of cases with endometrial hyperplasia (Table 2).

Measurement of endometrial thickness by TVUS showed a significant difference between normal and atrophic endometrium and between atrophic endometrium and endometrial polyp and a non significant difference between normal endometrium and endometrial polyp, normal endometrium and endometrial hyperplasia, atrophic endometrium and endometrial hyperplasia, endometrial polyp and endometrial hyperplasia (Table 3).

| Mean Endometrial Thickness | ||

|---|---|---|

| Normal endometrium | 12.38 ± 5.80 mm | |

| Endometrial atrophy | 4.88 ± 2.30 mm | |

| Endometrial polyp | 16.56 ± 11.30 mm | |

| Endometrial hyperplasia | 8.89 ± 5.37 mm | |

| P value | Significance | |

| Normal/Atrophy | 0.004 | Significant |

| Normal/Polyp | 0.339 | Non-significant |

| Normal/Hyperplasia | 0.218 | Non-significant |

| Atrophy/Polyp | 0.001 | Significant |

| Atrophy/Hyperplasia | 0.066 | Non-significant |

| Polyp/Hyperplasia | 0.069 | Non-significant |

Table 3: Endometrial thickness by 2D-TVUS in different diagnoses.

DH had the best sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV as a diagnostic procedure followed by SIS then TVUS (Table 4).

| Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | |||||

| TVUS | 52.9% | 89.4% | 56.3% | 88.1% | |

| SIS | 74.0% | 91.2% | 67.3% | 93.5% | |

| DH | 97.7% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 99.4% | |

| Endometrial polyp | |||||

| TVUS | 50.0% | 94.1% | 80.0% | 80.0% | |

| SIS | 87.5% | 94.1% | 87.5% | 94.1% | |

| DH | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | |

| Endometrial hyperplasia | |||||

| TVUS | 63.6% | 71.8% | 38.9% | 87.5% | |

| SIS | 54.5% | 94.9% | 75.0% | 88.1% | |

| DH | 90.9% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 97.5% | |

| Endometrial atrophy | |||||

| TVUS | 50.0% | 95.3% | 66.7% | 90.9% | |

| SIS | 62.5% | 95.3% | 71.4% | 93.0% | |

| DH | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | |

| Submucous fibroid | |||||

| TVUS | 87.5% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 97.7% | |

| SIS | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | |

| DH | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | |

Table 4: Comparison of sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values of TVUS, SIS & DH in assessment of uterine lesions.

ER scoring among glands showed a significant difference between normal and atrophic endometrium, normal and endometrial polyp, atrophic endometrium and endometrial polyp, atrophic endometrium and endometrial hyperplasia (Table 5).

| Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | |||||

| TVUS | 52.9% | 89.4% | 56.3% | 88.1% | |

| SIS | 74.0% | 91.2% | 67.3% | 93.5% | |

| DH | 97.7% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 99.4% | |

| Endometrial polyp | |||||

| TVUS | 50.0% | 94.1% | 80.0% | 80.0% | |

| SIS | 87.5% | 94.1% | 87.5% | 94.1% | |

| DH | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | |

| Endometrial hyperplasia | |||||

| TVUS | 63.6% | 71.8% | 38.9% | 87.5% | |

| SIS | 54.5% | 94.9% | 75.0% | 88.1% | |

| DH | 90.9% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 97.5% | |

| Endometrial atrophy | |||||

| TVUS | 50.0% | 95.3% | 66.7% | 90.9% | |

| SIS | 62.5% | 95.3% | 71.4% | 93.0% | |

| DH | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | |

| Submucous fibroid | |||||

| TVUS | 87.5% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 97.7% | |

| SIS | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | |

| DH | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | |

Table 5: ER and PR scoring (of both endometrial glandular cells and stromal cells) in different uterine lesions.

ER scoring among stroma showed a significant difference between normal and endometrial polyp, normal and endometrial hyperplasia, atrophic endometrium and endometrial polyp, atrophic endometrium and endometrial hyperplasia (Table 5).

PR scoring among glands showed a significant difference between normal and atrophic endometrium, atrophic endometrium and endometrial polyp, atrophic endometrium and endometrial hyperplasia (Table 5).

PR scoring among stroma showed a significant difference between normal and atrophic endometrium, normal and endometrial polyp, atrophic endometrium and endometrial polyp, atrophic endometrium and endometrial hyperplasia (Table 5).

ER expression in glands showed a significant difference while ER expression among stroma and PR expression among both glands and stroma showed a nonsignificant difference between endometrial polyp and surrounding endometrium (Table 6).

| P value | Significance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polyp/Surrounding Endometrium | ER | Glands | 0.006 | Significant |

| Stroma | 0.610 | Non | ||

| PR | Glands | 0.131 | Non | |

| Stroma | 0.792 | Non | ||

Table 6: Difference in expression of ER and PR between endometrial polyps and the surrounding endometrium of the same cases.

Discussion

Our study concluded that measurement of endometrial thickness using TVUS has limited value in differentiation of causes of thickened endometrium and SIS is superior in assessment of the uterine cavity. It can be used as the primary method for the detection of the uterine cavity among women with AUB. SIS improves the efficiency of TVUS as a diagnostic tool, especially with intra-cavitary lesions as endometrial polyps and SMF. DH remains the gold standard for assessment of the uterine cavity, but cannot replace the histopathology.

Our study found that the expression of ER and PR plays an important role in the pathogenesis of endometrial polyps and endometrial hyperplasia.

In our study endometrial polyp (32%) was the commonest endometrial lesion followed by endometrial hyperplasia (22%). Bingol et al. stated that 38% of patients with AUB had endometrial polyps and 28% had hyperplasia [8].

The diagnostic accuracy of DH was almost 100% in our study for all lesions, and gave just 2 false negative result by missing two cases of simple endometrial hyperplasia. The high accuracy of DH (approaching almost 100%) is in line with other studies [8-10].

SIS had high accuracy in diagnosis of intra-cavitary lesions, such as polyps and SMF. Regarding endometrial polyps, SIS had 2 false negative and 2 false positive (diagnosing a case of endometrial hyperplasia as a polyp due to the presence of intra-uterine debris (confirmed by hysteroscopy) [11].

However; SIS was less accurate in endometrial hyperplasia by giving 6 false negative and 6 false positive results (1 case was found to have a polyp and 2 cases were normal). This agrees with other study [12]. Most studies proved the high accuracy of SID with intra-cavitary lesions –mainly polyps and SMF [8,10,12].

TVUS missed half the polyps and had 24 false positive results of endometrial hyperplasia and failed to differentiate whether the thickened endometrium was due to an endometrial polyp, endometrial hyperplasia or even a normally thickened endometrium. That was similar to other studies [8,12].

We found that endometrial thickness was statistically significant only in cases of endometrial atrophy (thinner when compared to normal endometrium). It was not reliable in cases of endometrial polyps and endometrial hyperplasia. This is supported by Bingol et al. [8].

TVUS, SIS and DH all had 100% accuracy in diagnosing SMF. However; SIS and DH showed better description of the exact site and estimation of the percentage circumference projecting into the endometrial cavity, compared to TVUS. That was similar to other studies [11,13,14].

Overall sensitivity rates were 52.9% for TVUS, 74% for SIS and 97.7% for DH; while overall specificity rates were 89.4%, 91.2% and 100%, respectively. Overall PPV were 56.3%, 67.3% and 100% for TVUS,

SIS and DH respectively. Meanwhile, overall NPV were 88.1%, 93.5% and 99.4% respectively. Our study found that cases of endometrial atrophy showed significant (P value < 0.05) decreased expression of ER

in the glandular cells, and decreased PR expression in both glands and stroma; when compared to the normal endometrium [15].

Cases of endometrial hyperplasia showed significant (P value< 0.05) over-expression of ER in both glands and stroma; when compared to the normal endometrium. That was similar to other studies [16,17].

Cases of endometrial polyps showed significant (P value < 0.05) over-expression of ER in both glands and stroma and over-expression of PR in stromal cells when compared to the normal endometrium. These findings are similar to the results of other studies [18-20].

Antunes and colleagues studied ER and PR expression in the glandular epithelium and stroma of benign and malignant endometrial polyps of 390 postmenopausal with endometrial polyps who underwent surgical

hysteroscopy.

They concluded that polyps in postmenopausal patients have high ER expression in the stroma and glandular epithelium. However, this expression is lower in premalignant /malignant polyps compared with benign polyps. These results indicate that lower ER expression may be one more risk factor for the malignancy potential of polyps in postmenopausal females [21,22].

We recommend that SIS should be used as an initial routine investigation instead of TVUS in cases of AUB.

Authors’ Contribution

Ahmed L Aboul Nasr: Protocol/project development, Mostafa A Salem: Protocol/ project development, Sherine H Gad Allah: Data collection or management, Data analysis, Ahmed A Wali: Data collection or management, Data analysis, Ahmed M Maged: Manuscript writing/editing.

References

- AscherSM, Reinhold C (2002) Imaging of cancer of the endometrium. RadiolClin North Am 40: 563-576.

- Hatasaka H (2005) The evaluation of abnormal uterine bleeding. ClinObstetGynecol 48: 258-273.

- Davis PC, O'Neill MJ, Yoder IC, Lee SI, Mueller PR (2002) Sonohysterographic findings of endometrial and subendometrial conditions. Radiographics 22: 803-816.

- Parsons AK (2001) Saline infusion sonohysterography. Medica Mundi 45: 29-41.

- Emanuel MH, Verdel MJ, Wamsteker K,Lammes FB (1995)A prospective comparison of transvaginal ultrasonography and diagnostic hysteroscopy in the evaluation of patients with abnormal uterine bleeding: clinical implications. The American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 172:547-552.

- Koshiyama M, Yoshida M, Takemura M, Yura Y, Matsushita K, et al. (1996) Immunohistochemical analysis of distribution of estrogen receptors and progesterone receptors in the postmenopausal endometrium. ActaObstetGynecolScand 75: 702-706.

- Mittal K, Schwartz L, Goswami S, Demopoulos R (1996) Estrogen and progesterone receptor expression in endometrial polyps. International Journal of Gynecological pathology 15:345-348.

- Bingol B, Gunenc MZ, Gedikbasi A, Guner H, Tasdemir S, et al. (2011) Comparison of diagnostic accuracy of saline infusion sonohysterography,transvaginalsonography and hysteroscopy in postmenopausal bleeding. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics284:111-117.

- Buyukbayrak EE, KarageyimKarsidag AY, Kars B, Balcik O, Pirimoglu M, et al. (2010) Effectiveness of short-term maintenance treatment with cabergoline in microadenoma-related and idiopathic hyperprolactinemia. Arch GynecolObstet 282: 561-566.

- Karsidag AYK, Buyukbayrak EE, Kars B, Unal O, Turan MC (2010) Transvaginalsonography, sonohysterography, and hysteroscopy for investigation of focal intrauterine lesions in women with recurrent postmenopausal bleeding after dilatation & curettage. Arch GynecolObstet 281: 637-643.

- Kelekci S, Kaya E, Alan M, Alan Y, Bilge U, et al. (2005) Comparison of transvaginalsonography, saline infusion sonography, and office hysteroscopy in reproductive-aged women with or without abnormal uterine bleeding. FertilSteril 84: 682-686.

- Allison SJ, Horrow MM, Lev-Toaff AS.(2010) Pearls and Pitfalls in Sonohysterography. Ultrasound Clinics 5:195-207.

- Grimbizis GF, Tsolakidis D, Mikos T, Anagnostou E, Asimakopoulos E, et al. (2010) A prospective comparison of transvaginal ultrasound, sonohysterography and diagnostic hysteroscopy in the evaluation of endometrial pathology. Fertility and Sterility 94:2720-2725.

- Elsayes KM,Pandya A, Platt JF, Bude RO(2009) Technique and diagnostic utility of saline infusion sonohysterography. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 105: 5-9.

- Mavrelos D, Naftalin J, Hoo W, Ben-Nagi J, Holland T (2011) Preoperative assessment of submucous fibroids by three-dimensional saline contrast sonohysterography. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 38:350-354.

- Mylonas I, Jeschke U, Shabani N, Kuhn C, Kunze S, et al. (2007) Steroid receptors ERalpha, ERbeta, PR-A and PR-B are differentially expressed in normal and atrophic human endometrium. Histology and Histopathology. 22:169-176.

- Orejuela FJ, Ramondetta LM, Smith J, Brown J, Lemos LB, et al. (2005) Estrogen and progesterone receptors and cyclooxygenase-2 expression in endometrial cancer, endometrial hyperplasia, and normal endometrium. Gynecological Oncology97:483-488.

- Pungal A, Balan R, Cotutiu C (2010) Hormone receptors and markers in endometrial hyperplasia. Immunohistochemical study. [Article in Romanian] Revista medico-chirurgicala a Societatii de Medici siNaturalisti din Iasi [Medical and Surgical Journal of the Society of Physicians and Naturalists of Iasi] 114:180-184.

- Sant’Ana de Almeida EC, Nogueira AA, Candido dos Reis FJ, ZambelliRamalho LN, Zucoloto S (2004)Immunohistochemical expression of estrogen and progesterone receptors in endometrial polyps and adjacent endometrium in postmenopausal women. Maturitas49:229-233.

- Inceboz US, Nese N, Uyar Y, Ozcakir HT, Kurtul O, et al. (2005) Hormone receptor expressions and proliferation markers in postmenopausal endometrial polyps. Gynecologic and Obstetric Investigation 61: 24-28.

- Lopes RG, Baracat EC, de Albuquerque Neto LC, Ramos JF, Yatabe S, et al. (2007) Analysis of estrogen- and progesterone-receptor expression in endometrial polyps. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 14: 300-303.

- Antunes A Jr, Vassallo J, Pinheiro A, Leão R, Neto AM, et al. (2014) Immunohistochemical expression of estrogen and progesterone receptors in endometrial polyps: A comparison between benign and malignant polyps in postmenopausal patients. OncolLett 7: 1944-1950.

Relevant Topics

- Advanced Endometrial Ablation Techniques

- Biomarkers and Molecular Diagnosis of all Gynaecologic Cancers

- Cervical Erosin

- Clinical Gynecologic Oncology

- Cysts and Ovaries

- Epidemiology of Gynecologic Cancers

- Fallopian Tube Cancer

- Gestational Trophoplastic Tumors

- Gynecological Oncology

- Neuroblastoma Cancer

- Omentum Cancer

- Oncofertility

- Ovarian Cancer

- Ovarian Cancer Prognosis

- Ovarian Tumors

- Pathological aspects and molecular pathology of all Gynecologic Cancers

- Premature Ovarian Failure

- Primary Peritoneal Cancer

- Quality of Life of Patients with Gynecologic Cancers

- Reproductive Cancer

- Socio- Psychological Aspects of Gynecological Cancers

- Targeted Molecular Therapy for all Gynaecologic Cancers

- Uterine Cancer

- Vaginal Cancer

- Vulva Cancer

- Womb Cancer

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 14430

- [From(publication date):

July-2016 - Aug 28, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 13449

- PDF downloads : 981