Review Article Open Access

Viral Haemorrhagic Fever in North Africa; an Evolving Emergency

Mohamed A Daw1,3* and Abdallah El-Bouzedi2In association with Libyan Study Group of Hepatitis & HIV

1Department of Medical Microbiology, Faculty of Medicine, Tripoli, Libya

2Department of Laboratory Medicine, Faculty of Biotechnology, Tripoli, Libya

3Professor of Clinical Microbiology and Microbial Epidemiology, Acting Physician of Internal Medicine, Scientific Coordinator of Libyan National Surveillance Studies of Viral hepatitis & HIV, Tripoli, Libya

- *Corresponding Author:

- Mohamed A Daw

Department of Medical Microbiology, Faculty of Medicine

Tripoli, Libya

Tel: 00218912144972

Fax: 00218213612231

Email: mohamedadaw@gmail.com

Received date: December 11, 2014; Accepted date: February 26, 2015; Published date: February 28, 2015

Citation: Mohamed A Daw and Abdallah El-Bouzedi (2015) Viral Haemorrhagic Fever in North Africa; an Evolving Emergency. J Clin Exp Pathol 5:215. doi:10.4172/2161-0681.1000215

Copyright: © 2015 Daw MA, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Clinical & Experimental Pathology

Abstract

Viral hemorrhagic fever has been associated with high mortality rate which brought serious concern for public health worldwide and prompted a sense of urgency to halt this infection. The clinical symptoms are very general and could be easily missed, consisting of onset of fever, myalgia, and general malaise accompanied by chills. In unstable countries of North Africa with fragile health services complicated with armed conflicts and population displacement, such infections could be easily confused with other local parasitic and viral diseases. Libya has the longest coast in North Africa facing the South European region. Emerging of Viral hemorrhagic fever in this region will pose an evolving risk to the European countries and thus worldwide. An outbreak of unidentified VHFs was reported in June/July 2014 among twenty three African patients from immigrants encamps in North West of Libya, twelve of them reported dead. The clinical and laboratory evidences strongly suggest VHF as the likely cause. Since then no more similar cases were reported till February 2015. With the arrival of viral hemorrhagic fevers in North-West of Libya, the South European countries is now at severe risk, then it is only a matter of time before it becomes apparent in developed countries. This review aims to highlight a recent spread of VHFs in North Africa in the light of political instability associated with massive immigration from the endemic areas of West African countries.

Keywords

Viral hemorrhagic fever; Libya; North Africa; Ebola virus; African immigrants

Introduction

Viral haemorrhagic fevers (VHFs) are severe viral infections capable of causing vital death associated with multi-organ failure resulting in high mortality rates. They cause severe epidemics resulting in a catastrophic situation which can interrupt the normal life, commerce or social structure of a community [1]. This is particularly prevailed among poor African countries, especially the tropical area; the natural niche of such viruses [2]. Nowadays, in Africa many viruses are known to cause haemorrhagic fevers including Ebola, Magdeburg and yellow fever. Although these diseases have genetic and antigenic differences, they will be considered together as they have very similar transmission, clinical presentations and management [3]. The floviruses, Ebola and Marburg, may cause epidemics, with a high case fatality rate, while Lassa has a lower case fatality rate [4,5]. Recently Ebola outbreaks increasingly expand causing widespread concern regarding severe symptoms, high fatality rates and fear of epidemic or pandemic spread associated with massive immigration to non-endemic countries in Africa and Europe [6,7]. WHO however, has reported that over 20000 cases were infected and 7600 were probably dead. Immigration from Africa was influenced by political instability and armed conflicts in North Africa particularly Libya, which resulted in a massive population displacement [8,9]. Such emerging infectious diseases form a major threat of global spread, if it comes out of Africa. Hence then, there is an urgent need to expand surveillance efforts for most of the VHFs in other African countries, particularly those who are at a short distant of the endemic areas and could be easily reached by immigrants [10,11].

Libya is the second largest country in Africa and seventeenth worldwide with the longest coast in the Mediterranean facing the Southern European Countries. This country is known as the ‘gateway to Africa’ bordering six different countries, where infectious diseases are considered to be endemic particularly among the sub-saharan ones. The country has an area of 1,775,500 km2 and a population reported in mid-2006 as 5,323,991, giving a population density of 2.9 persons per km2. It boasts the highest literacy and educational enrolment in North Africa and among the Arab nations [12,13]. Life expectancy (73 years) and health-adjusted life expectancy (64 years) are among the best in the Middle East and North Africa [14]. The great economic visibility and the geographical location of the country has attracted a lot of young people from all over Africa for both work and immigration. This could be reflected immensely on the geoepidemiology of infectious disease particularly among Mediterranean basin countries. In recent years Libya has attracted worldwide attention as many Africans transit through it to enter Southern Europe illegally, with the possibility of transmitting infection in transit, or at the destination [15,16]. After the Libyan armed conflict (February-2011), over 80,000 illegal Africans immigrated annually via the Libyan coast [8,17,18] . Lack of strong central government and the deterioration of the health services make it difficult to guard the long borders of the country and to control any emerging infectious disease [19]. In the summer of 2014, heavy fighting between the two strongest -armed revivals of February revolt has led to immigration of more than half million people from the capital alone. In the north west of the country an unusual emerging vital infectious disease has occurred among African immigrants encamps. The concern has raised the possibility of introduction and transmission of hemorrhagic viruses in Libya and thus EU associated with the ongoing and rapidly evolving outbreaks in Tropical and West African countries.

Viral Hemorrhagic Fevers in Africa

The term “viral hemorrhagic fever”(VHF) is used to describe the spectrum of disease caused by members of four different families of enveloped RNA viruses [20]. Currently, there are over 20 members in this group. However, some of them were associated with high morbidity and mortality particularly in tropical areas worldwide. Primary transmission to human and nonhuman primates remains unclear. Recent outbreaks have been associated with multiple introductions into the population, indicating the circulation of distinct strains that have evolved in reservoir species that occupy different ecological niches [21]. In the endemic areas, they are causing longlasting and slow burning epidemics, which can interrupt the normal life, commerce or social structure of a community [22,23]. In Africa six viral hemorrhagic fevers are known to occur; yellow fever, Rift Valley fever, Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever, Lassa fever, Marburg virus disease, and Ebola hemorrhagic fever. The endemic range of these infections is constrained by the ecological and climatic requirements of their hosts and vectors, so that they exist mainly in predictable geographical areas [24,25]. Table 1 shows the etiological and epidemiological aspects of VHFs in Africa.

| Type of VHFs | Agent | Vector | Epidemiological risk | Geographical location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCHF | Bunyavirus | Hyalomma tick | Farmers In endemic country-Zoonotic | Central and South Africa |

| LASSA | Lassa virus (arenavirus ) | NSK | -Healthcare and Lab workers -Tourist Activities(camping, Hiking) -Food contaminated with rats |

Sub-Saharan westAfrica |

| Ebola | EBOV | NSK | -Contact with infected persons -Health care and Lab workers -Fruit bats -Tourists, Immigration |

West-Central, SouthAfrica |

| Marburg | MARV | uncertain | Uncertain | uncertain |

| Yellow fever (YF) | Favivirus- Aedes | Aedes | mosquitoes-insects | Tropical area, Ivory Coast- PREVENTABLE-vaccines |

| Rift Valley fever (RVF) | phlebovirus | Domestic Livestock | Zoonosis | Kenya |

Table1: Viral hemorrhagic Fevers in Africa; Pathogens and epidemiological consideration.

The regulations of newly emerging African Union allow African people to move and work easily in most of African countries without visa. Citizens can cross several different countries and ecologies in a short time to seek better life and high-quality health services. Families are often dispersed across several countries, including high-risk areas for VHFs and visit between them. Hence, VHFs, can be easily exported along established travel routes to distant countries, where they place great burden on medical and public health services [26,27].

Four main types of African VHFs are of concern to non-epidemiccountries. They also fulfill the definition for hazard Group 4 pathogens and capable of transmission from one person to another [28,29]. These VHFs are: Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever (CCHF), the filovirus haemorrhagic fevers (Marburgand Ebola) and Lassa fever.

Considering the epidemiological risks for VHFs, ebola virus appears to be the most likely one easily transmitted among humans within the neighboring countries in Africa [30]. Ebola was first appeared in 1976 in Sudan and Congo and then spread to the villages surrounding the Ebola river from which the disease takes its name [31]. In community the Ebola spreads through human-to-human transmission, with infection resulting from direct contact (through broken skin or mucous membranes) with the blood, secretions, organs or other bodily fluids of infected people, and indirect contact with environments contaminated with such fluids [32]. Those who recovered from the disease can still transmit the virus through their internal fluids such as semen for up to 61 days after recovery from illness. Since its discovery until 2014 there were 27 recognized EVD outbreaks centered on central and west equatorial Africa totaling around 2,460 documented cases [33]. Nowadays the virus appose special problem for health care workers, tourists, animal lovers and overall immigrants.

During 2014 a major outbreaks occurred in West African countries involving four countries; Guinea, Liberia, Sera Leone and Mali [34]. The hardest-hit countries are among the poorest in the world. They have only recently emerged from years of conflict and civil war that have left their health systems largely destroyed or severely disabled [35]. Immerging of multiple large outbreaks over a short period of time among these countries will be of vital consequence to nonepidemic countries in North Africa. Massive immigration to such wealthy countries will be an important issue in the spread of VHFs. Hence, cross borders transmission should be taken to consideration in preventing such a gargantuan disease.

Libyan Event; Setting and Circumstances

As of June-July, 2014, twenty-three patients with unusual haemorrhagic symptoms from African Immigrant encampments located in North -West of Libya, 60 km west of Tripoli were reported. Detailed clinical evaluations were done for the patients and clinical records were analysed. The clinical definition of VHF used in this epidemiologic survey was based on previous studies carried in West Africa [36]. A recent case of an African person arrived from West Africa with the following symptoms: abdominal pain, nausea, diarrhea, headache, arthralgias, breathing difficulty, severe pain along with unexplained haemorrhage represented by bloody stool, bloody skin spots, a maculopapular rash, epistaxis, and haematemesis [37].

The laboratory diagnosis was carried out using serological tests (multiple sequential blood samples collected from each patient in addition (IF) to urine, stool and sputum) for all patients (n=23). Liver function test, renal function tests and differential-diagnostic tests for parasitic, bacterial and viral infections were determined for blood, stool and urine to exclude malaria, Brucellosis typhoid fever, shigellosis, leptospirosis, rickettsial infections, viral hepatitis, meningococcal infections, gram-negative sepsis [38].

The patients’ ages were between 21 and 42 years (mean=+31.5 years). All of them were males coming from different African countries including; Guinea-7, Liberia-3, Sierra Leone-5, Mali-3, Niger-2, and Ivory-coast 3 persons. The disease onset occurred between June and 21 July, and patients entered the hospital between 18 June and 27 July. All patients were brought from the same immigration encompass. The incubation period could not be determined among the patients and twelve patients died with an overall fatality rate of 52.2% after a mean of 3 days (range 2-7 days) after disease onset, although, 11 survivors were reported. Tests for parasites in blood and stool, blood cultures, and cultures of urine were negative. On the basis of clinical, biologic, and serologic data, a diagnosis of VHF infection was suspected in 15 cases among the hospitalized patients. Although the complete virus could not be isolated, the clinical signs and symptoms of the patients are clearly evident as shown in Table 2. The patients’ conditions deteriorate quickly within two or three days. Patients have an acute bleedings from their gums, respiratory and digestive tracts. Skin bruises, Internal organ involvement and failure are noticeable.

| Clinical Characteristics (symptoms and signs) | Patients (%) with | Patients without | Not reported |

|---|---|---|---|

| A-Clinical symptoms | |||

| Nausea, vomiting and diarrhea | 17 | 04 | 02 |

| Headache | 21 | 02 | 0.0 |

| Abdominal pain | 14 | 04 | 05 |

| Bleeding signs | 17 | 02 | 04 |

| Cough and chest pain | 08 | 06 | 09 |

| Weakness & loss of concentration | 14 | 05 | 04 |

| Joint & muscle pain | 11 | 07 | 05 |

| B-Clinical signs | |||

| Fever | 23 | 00 | 00 |

| Cough and hiccups | 10 | 06 | 07 |

| Breathing disturbance | 08 | 09 | 06 |

| Skin rash | 07 | 11 | 05 |

| Spleen and liver involvement | 09 | 05 | 09 |

| C-Bleeding signs | |||

| Epistaxis & gum bleeding | 17 | 02 | 04 |

| Hematemesis | 14 | 06 | 03 |

| Melena and Hematuria | 10 | 07 | 06 |

Table 2: Signs and symptoms observed in 23 suspected cases of VHF reported in North West of Libya August 2014.

The first suspected case was 27- year-old man arrived from Guinea within two weeks and was planning to immigrate to Europe via professional immigrant-trafficking holders in North-West of Libya. The patient died within two days from fulminant hemorrhagic disease characterized by frank hemorrhage associated skin subcutaneous bleeding, gum bleeding, sever pain and high temperature. The early onset manifestations appeared more suggestive VHF; very pronounced sever sore throat, mucosal and internal bleeding lead to immediate death. The date of disease onset was not easily available for most suspected cases, and it was often disputable. However, the date of death was invariably available and rarely in dispute. However, at that time, many people had fled the area in terror which occurred in west and North west of Libya during the summer of 2014; therefore, it was difficult to conduct any investigation and assess any further exposure within the African immigrants encamps as well as Libyan local population.

Possible Scenarios

VHF has been characterized by clear epidemiological features which allow them to pose additional risks that are difficult to control, particularly within the nearby countries from the endemic areas of Africa. These were clearly mirrored by a highly variable incubation period of one to 25 days and the long positive period of some recovered patients [39]. The spread of the newly emerged infectious diseases are rapidly enhanced by fast population growth, massive migration and easy inter border travelling. In post-conflict settings, severe disruption to health systems invariably leaves populations at higher risk of infectious diseases and in greater need of health provision than more stable resource-poor countries [40]. The spread of VHFs in North-west of Libya could be influenced by such concomitant factors.

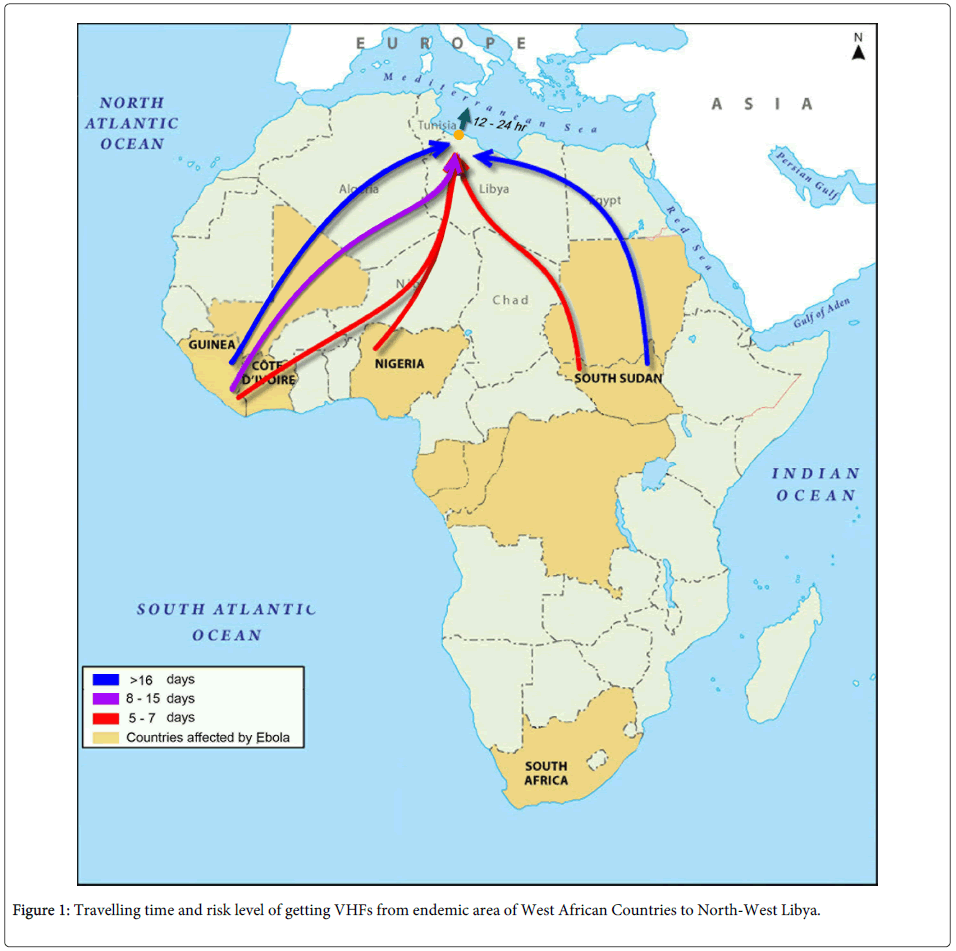

Based on the epidemiological dynamics of VHFs illustrated by case fatality ratio, timing of new outbreaks, and the strength of human-tohuman transmission, the Libyan outbreak goes in concordance with those of West-Africa as shown in Figure 1. Early this year there is an ongoing outbreak of haemorrhagic fever in Guinea, Liberia Sierra Leone and Mali [41].

In Guinea as of 3 June 2014, the Ministry of Health of Guinea has reported 344 cumulative cases, of which 215 have died (CFR=63%). Of these cases, 207 (60%) have been laboratory confirmed, 81 (24%) classified as probable and 56 (16%) as suspected. Countrywide, 987 contacts are currently being followed [42,43]. On 23 May 2014, a suspected case of EVD who had travelled from Sierra Leone to Liberia was admitted to the hospital and as of 4 June 2014, Liberia reported 13 cases [44]. In Sierra Leone as of 5 June 2014, according to WHO, the number of clinical EVD cases has risen to 81 (31 confirmed, three probable and 47 suspected) including six deaths (three confirmed, three probable) [42,45]. In Mali, the Ministry of Health has reported six suspected cases as of 7 April 2014, two of which have tested negative for Ebola virus infection [46]. The typical natural history of the VHF begins with an average incubation period of 1-2 weeks before the appearance of mild symptoms. Lack of hospitalization of these patients will increase the predicted epidemic size of these viruses [47].

Citizens from these Western and Sub-Saharan countries seek Libya not only because of better living conditions but they can easily escape to South Europe within five days from their native country. Such opportunity became easier nowadays as a result of the unstable political situation in Libya. The time needed to be in North West of Libya overlaps evidently with incubation period of VHFs as shown in Table 3. As the epidemic evolved in Guinea and became clearly documented in June 2014. On 23rd May, 2014, a suspected case of VHF who had travelled from Sierra Leone to Liberia resulted in infecting eleven contacts including five health care workers. Furthermore the cases were risen in Liberia to reach 81 by June 2014. The Libyan documented cases were reported among the African encampss coming from these countries by June-July 2014. Epidemic and surveillance evidences highlight the possibility of an unusual hemorrhagic fever in North West of Libya characterized by;

| Country | Guinea | Liberia | Sierra Leone | Mali | Libya |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases of VHF | 344 | 23 | 81 | 07 | 23 |

| Confirmed | 207 | 06 | 31 | 01 | 0 |

| Probable | 81 | 02 | 03 | 00 | 09 |

| Suspected | 56 | 05 | 47 | 06 | 14 |

| Death | 215 | 10 | 06 | 00 | 12 |

| Infection P* | January/July | March/June | May/June | February/April | June/August |

| Overlapping P** | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

Overlapping period**; time (days) needed for Ebola to cause active infection if transmitted to another country (i.e. Libya) via infected people.

Table 3: Epidemiological interaction and overlapping between the out breaks of VHFs in West and North African Countries.

A- Being endemic among immigrant African rather than resident Libyans

B- The timing concordance (overlaps) with the epidemiciy-timing of EHF out breaks in West Africa

C- The clinical symptoms and signs associated deteriorating type of hemorrhage of high mortality rate and high mortality rate highlights the features of VHF

D- Laboratory tests, which indicate the parameters of VHF despite the lack of isolation and the confirmation of the Virus

Although this illustrative scenario is not conclusive, it should be considered as a “best possibility”. The probabilities herein are, based upon the travelling time of an infected patient from the endemic countries to North West of Libya. This confined clearly and evidently with incubation period of the VHF infection.

Threat Assessment

The most important epidemiological quantity to estimate for an infectious disease is typically the basic reproductive ratio, R 0 defined as the expected number of secondary cases produced per primary case early in the epidemic [48]. When R 0 is greater than 1, the expectation is that a new epidemic will eventually infect a significant percentage of the population. Previous attempts to estimate R 0 for VHF viruses have found values between 1.34 and 3.65 by fitting compartmental epidemic models to the incidence over time of the large outbreaks in Western Africa [49,50]. There is a dearth of information on the spread and worldwide destiny of VHFs. In Africa, conflicts, breakdowns in health care systems, and unrestricted people transportation through open borders have promoted the re-emergence of such viruses.

Early this century, different African resident HV tropical viruses have been involved in a major out breaks outside Africa. Dengue out breaks has been reported in Djibouti, Yemen and Saudi Arabia. Now it is a reside endemic in the western and southern regions of Saudi Arabia, with peaks of infection appearing in 2006 and 2008 [51]. Another emerging viral diseases are Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever (CCHF) and Rift Valley fever which reported in Yemen, Saudi Arabia, Oman and lately Iran [52,53]. These recorded outbreaks outside Africa, are an alarming sign of geo-dynamics features of such viruses and thus highlights the need an urgent surveillance programs and international intervention to stop the spread of VHFs. The current situation in North-West of Libya goes parallel to these reported epidemics. The investigation concludes that these African patients has symptoms compatible with Ebola fever and they were at high risk exposure in native affected country in the past 21 days. This indeed highlights the risk of spreading EHF to Northern Africa. The recent increase in the number of the out breaks within the African countries characterized by large number if infected people (>500 case this year (2014), and high mortality rate (up to 85%)) among those infected. This may suggest the difference in the virus reservoir, gene variability, viral mutation; however further studies are needed to highlight such expectation.

The time that the virus may take to reach North Africa is few days and then hours to be in South Italy (If unchecked). If it is spreading outside of Africa, then it is only a matter of time – perhaps several weeks – before it becomes apparent in developed countries. However, immigrants spend a variable lapse of time in the immigration camps in North Africa before embarking for Southern Italy. Hence, the permanence in these camps may affect the threat locally and to the northern side of the Mediterranean Sea. Clearly, newer approaches and strategies that can effectively limit the spread of infections including interventions or chance extinction are needed.

Prevention and Control

Emerging of infectious viral diseases arise without warning, even with global efforts aimed at tracking pathogens early and at the source; a fact most recently evidenced by the current outbreak of Ebola virus affecting multiple West African countries. The arrival of such viruses in non-endemic countries has created much justifiable concern and poses a serious global problem [54]. Lack of information regarding methods of transmission, quick laboratory specific diagnostic tests, and efficient treatment of the VHFs necessitates an efficient preventive and control measures [55,56]. Therefore, efforts and international attempts should be combined to stop the spread of these emerging viral diseases. The most important parameters for the control of these epidemics include; time of intervention, epidemic size, tracing the infected patients, those who are at risk, hospitalization and institution of interceptive measures. The responses to VHFs outbreaks are linked to surveillance and early detection strategies of these viruses which clearly varied from endemic and non-endemic countries as shown in Table 4.

| *Countries Affected - Emergency alert - Behavioral and social interventions - Implementation of National Epidemiological and surveillance programs - Introduction of accurate Laboratory investigation and Clinical management - Quarantine - Treatment and Vaccination [If applicable] *Countries at risk of VHFs - Risk assessment - Tracing - Infection control and Standard precautions - Restrict travel to affected areas - Port of entry control (driving , sea or air) *Global cooperation -Immigration control -Worldwide cooperation to prevent “unprecedented epidemics” of deadly VHFs. - Funded research particularly regarding deforestation, viral mutation, diagnostic tests and treatment -International regulation should be adapted including -[ IHR- International Health Regulations(IHR) 2005, Global Health Security, The Public Health Emergency of International Concern -PHEIC]. |

Table 4: Guide lines and applicable measures to control VHFs.

Countries infected by the virus (endemic areas)

Affected countries, lack the infra-structure health services, well trained health care workers and resources. The poor living conditions and the lack of water and hygiene in the infected countries pose a serious risk that this epidemic will become a crisis. The outbreaks in multiple locations across the country borders made it difficult to control. This was further complicated with social and habitual rituals associated with Funeral practice of infected dead bodies. Hence, emergency measures should be implemented both at national and international levels to contain these outbreaks and prevent further spread of these deadly viruses [57].

Countries at risk (non-endemic areas)

In countries at risk of the introduction or spread of VHFs, national policies for managing cases focus on those infections which are known to be transmissible from person to person and could therefore cause secondary cases or outbreaks. Persons coming from infected area at the time of epidemics should be known to health authority. If a diagnosis cannot be laboratory confirmed in a timely manner, contact tracing should be considered if the clinical and epidemiological picture is strongly suggestive of VHF as the likely diagnosis

Conclusion

The emergence of an unusual haerorrhgic fever in North Africa should be taken with special consideration as the epidemiological emergence; as it will lead to subsequent spread in a new population. Special reference should be pointed to close South European countries and then jumping to other EU countries. We conclude that, although the dynamics of this new invasion remain poorly understood the pathogen emergence is unpredictable. Emerging pathogens tend to share some common traits, and jump from one country to another and pushed greatly by massive population displacement and engulfment of massive immigration. Hence then international efforts should be combined to trace, prevent and tackle the spread of such treats and Global Health Security should be amended and applied particularly among North African countries.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Bannister B (2010) Viral haemorrhagic fevers imported into non-endemic countries: risk assessment and management. Br Med Bull 95: 193-225.

- Li YH, Chen SP (2013) Evolutionary history of Ebola virus. Epidemiol Infect 16:1138-1145.

- Ansari AA (2014) Clinical features and pathobiology of Ebolavirus infection. J Autoimmun55: 1-9.

- Vittecoq M, Thomas F, Jourdain E, Moutou F, Renaud F, et al. (2014) Risks of emerging infectious diseases: evolving threats in a changing area, the mediterranean basin. TransboundEmerg Dis 61: 17-27.

- Jeffs B1 (2006) A clinical guide to viral haemorrhagic fevers: Ebola, Marburg and Lassa. Trop Doct 36: 1-4.

- Tumwine JK (2014) Ebola and other issues in the health sector in Africa. Afr Health Sci 14: i-iii.

- Changula K,Kajihara M, Mweene AS, Takada A (2014) Ebola and Marburg virus diseases in Africa: increased risk of outbreaks in previously unaffected areas? MicrobiolImmunol 58: 483-491.

- Daw MA, El-Bouzedi A, Dau AA (2015) Libyan armed conflict-2011; mortality, injury and population displacement. African Journal of Emergency Medicine.

- Dau AA,Tloba S, Daw MA (2013) Characterization of wound infections among patients injured during the 2011 Libyan conflict. East Mediterr Health J 19: 356-361.

- Parkes-Ratanshi R,Ssekabira U, Crozier I (2014) Ebola in West Africa: be aware and prepare. Intensive Care Med 40: 1742-1745.

- Gostin LO,Lucey D2, Phelan A1 (2014) The Ebola epidemic: a global health emergency. JAMA 312: 1095-1096.

- Hamdy A (2007) Libya Country Report: Survey of ICT andEducation in Africa.

- El Oakley RM,Ghrew MH, Aboutwerat AA, Alageli NA, Neami KA, et al. (2013) Consultation on the Libyan health systems: towards patient-centred services. Libyan J Med 8.

- Clark N (2004) Education in Libya. World Education News and Reviews: World Education Services.

- Daw MA, El-Bouzedi A; In association with Libyan Study Group of Hepatitis & HIV (2014) Prevalence of hepatitis B and hepatitis C infection in Libya: results from a national population based survey. BMC Infect Dis 14: 17.

- Daw MA,Shabash A2, El-Bouzedi A3, Dau AA4; Association with the Libyan Study Group of Hepatitis & HIV (2014) Seroprevalence of HBV, HCV & HIV co-infection and risk factors analysis in Tripoli-Libya. PLoS One 9: e98793.

- Laub K (2011) Libyan estimate: at least 30,000 died in the war. Associated Press (San Francisco Chronicle).

- Levine AC,Shetty P (2012) Managing a front-line field hospital in Libya: Description of case mix and lessons learned for future humanitarian emergencies. African Journal of Emergency Medicine2: 49-52.

- Coutts A,Stuckler D, Batniji R, Ismail S, Maziak W, et al. (2013) The Arab Spring and health: two years on. Int J Health Serv 43: 49-60.

- Bühler S, Roddy P, Nolte E, Borchert M (2014) Clinical documentation and data transfer from Ebola and Marburg virus disease wards in outbreak settings: health care workers' experiences and preferences. Viruses 6:927-937.

- Woolhouse ME, Haydon DT, Antia R (2005) Emerging pathogens: the epidemiology and evolution of species jumps. Trends EcolEvol 20: 238-244.

- Weiss RA, McMichael AJ (2004) Social and environmental risk factors in the emergence of infectious diseases. Nat Med 10: S70-76.

- Leach M (2008)Haemorrhagic fevers in Africa: Narratives, politics and pathways of disease and response. STEPS centre.

- Peterson AT, Bauer JT, Mills JN (2004) Ecologic and geographic distribution of filovirus disease. Emerg Infect Dis 10: 40-47.

- Groseth A,Feldmann H, Strong JE (2007) The ecology of Ebola virus. Trends Microbiol 15: 408-416.

- Gonzalez JP,Herbreteau V, Morvan J, Leroy EM (2005) Ebola virus circulation in Africa: a balance between clinical expression and epidemiological silence. Bull SocPatholExot 98: 210-217.

- Daw MA,Dau AA (2012) Hepatitis C virus in Arab world: a state of concern. ScientificWorldJournal 2012: 719494.

- Isaäcson M (2001) Viral hemorrhagic fever hazards for travelers in Africa. Clin Infect Dis 33: 1707-1712.

- RisiGF, Arminio T (2013) Biosafety Issues and Clinical Management of Hemorrhagic Fever Virus Infections. In: Singh SK, RuzekD (eds) Viral Hemorrhagic Fevers.CRC Press, London.

- Mbonye AK,Wamala JF2, Nanyunja M3, Opio A4, Makumbi I5, et al. (2014) Ebola viral hemorrhagic disease outbreak in West Africa- lessons from Uganda. Afr Health Sci 14: 495-501.

- Baron RC, McCormick JB, Zubeir OA (1983) Ebola virus disease in southern Sudan: hospital dissemination and intrafamilial spread. Bull World Health Organ 61: 997-1003.

- Colebunders R,Borchert M (2000) Ebola haemorrhagic fever--a review. J Infect 40: 16-20.

- Gatherer D1 (2014) The 2014 Ebola virus disease outbreak in West Africa. J Gen Virol 95: 1619-1624.

- Wakil I (2014) Spread of Hemorrhagic/Infectious Diseases. NEWSLETTER 9(4).

- Chan M (2014) Ebola virus disease in West Africa--no early end to the outbreak. N Engl J Med 371: 1183-1185.

- Ksiazek TG, Rollin PE, Williams AJ, Bressler DS, Martin ML, et al. (1999) Clinical virology of Ebola hemorrhagic fever (EHF): virus, virus antigen, and IgG and IgM antibody findings among EHF patients in Kikwit, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 1995. J Infect Dis179: S177-S187.

- Georges AJ, Leroy EM, Renaut AA, Benissan CT, Nabias RJ, et al. (1999) Ebola hemorrhagic fever outbreaks in Gabon, 1994-1997: epidemiologic and health control issues. J Infect Dis 179 Suppl 1: S65-75.

- Kortepeter MG, Bausch DG, Bray M (2011) Basic clinical and laboratory features of filoviral hemorrhagic fever. J Infect Dis 204 Suppl 3: S810-816.

- Muyembe-Tamfum JJ,Mulangu S, Masumu J, Kayembe JM, Kemp A, et al. (2012) Ebola virus outbreaks in Africa: past and present. Onderstepoort J Vet Res 79: 451.

- Roome E, Raven J, Martineau T (2014) Human resource management in post-conflict health systems: review of research and knowledge gaps. Confl Health 8: 18.

- Baize S,Pannetier D, Oestereich L, Rieger T, Koivogui L, et al. (2014) Emergence of Zaire Ebola virus disease in Guinea. N Engl J Med 371: 1418-1425.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (2014) Outbreak of Ebola virus disease in West Africa. Stockholm: ECDC.

- WHO Regional Office for Africa (2014) Ebola virus disease, West Africa (Situation as of 05 June 2014) [internet]. 2014 [cited 2014 Jun 4].

- WHO Regional Office for Africa (2014) Ebola virus disease, West Africa (Situation as of 01 June 2014) [internet]. 2014 [cited 2014 Jun 4].

- UNICEF-Liberia (2014) Ebola virus disease, SitRep#22 (Situation as of 02 June 2014) [internet].2014 [cited 2014 Jun 2].

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (2014) Outbreak of Ebola virus disease in West Africa. Stockholm: ECDC; 2014.

- Umeora OU, Emma-Echiegu NB, Umeora MC, Ajayi N (2014) Ebola viral disease in Nigeria: The panic and cultural threat. African Journal of Medical and Health Sciences 13: 1-5.

- Diekmann O,Heesterbeek JA, Metz JA (1990) On the definition and the computation of the basic reproduction ratio R0 in models for infectious diseases in heterogeneous populations. J Math Biol 28: 365-382.

- Ferrari MJ,Bjørnstad ON, Dobson AP (2005) Estimation and inference of R0 of an infectious pathogen by a removal method. Math Biosci 198: 14-26.

- Legrand J,Grais RF, Boelle PY, Valleron AJ, Flahault A (2007) Understanding the dynamics of Ebola epidemics. Epidemiol Infect 135: 610-621.

- Ahmed MM (2010) Clinical profile of dengue fever infection in King Abdul Aziz University Hospital Saudi Arabia. J Infect DevCtries 4: 503-510.

- Scrimgeour EM, Mehta FR, Suleiman AJ (1999) Infectious and tropical diseases in Oman: a review. Am J Trop Med Hyg 61: 920-925.

- Chinikar S,Ghiasi SM, Moradi M, Goya MM, Reza Shirzadi M, et al. (2010) Phylogenetic analysis in a recent controlled outbreak of Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever in the south of Iran, December 2008. Euro Surveill 15.

- Memish ZA, Al-Tawfiq JA (2014) The Hajj in the time of an Ebola outbreak in West Africa. Travel Med Infect Dis 12: 415-417.

- Martin-Moreno JM,Llinás G2, Hernández JM3 (2014) Is respiratory protection appropriate in the Ebola response? Lancet 384: 856.

- Maurice J (2014) WHO meeting chooses untried interventions to defeat Ebola. Lancet 384:e45-46.

- Vittecoq M, Thomas F, Jourdain E, Moutou F, Renaud F, et al. (2014) Risks of emerging infectious diseases: evolving threats in a changing area, the mediterranean basin. TransboundEmerg Dis 61: 17-27.

Relevant Topics

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 16554

- [From(publication date):

April-2015 - Aug 31, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 11824

- PDF downloads : 4730