Research Article Open Access

Assessing Climate Change Impacts on Ecosystem Services and Livelihoods in Ghana: Case Study of Communities around Sui Forest Reserve

Emmanuel Boon1* and Albert Ahenkan21Human Ecology Department, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Belgium

2Human Ecology Department, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Belgium

- *Corresponding Author:

- Emmanuel Boon

Professor, Human Ecology Department

Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Belgium

Tel: +32 477 31 43 43

E-mail: eboon@vub.ac.be

Received date: October 31, 2011; Accepted date: April 19, 2012; Published date: April 23, 2012

Citation: Boon E, Ahenkan A (2011) Assessing Climate Change Impacts on Ecosystem Services and Livelihoods in Ghana: Case Study of Communities around Sui Forest Reserve. J Ecosyst Ecogr S3:001. doi:10.4172/2157-7625.S3-001

Copyright: © 2011 Boon E, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Ecosystem & Ecography

Abstract

The link between climate change, ecosystem services and livelihood in developing countries has been well established. Tropical forest ecosystems are particularly of great importance to the livelihood of millions of people. Recent decades of escalating climate change impacts on ecological systems and livelihoods worldwide and the vulnerability of forest dependent communities raise concerns about the consequences of ecosystem changes for human well-being. Applying the human ecological approach, this paper examines climate change impacts on ecosystem services and livelihoods of the communities around the Sui River Forest Reserve (SRFR) in the Sefwi Wiawso District in the Western Region of Ghana, the main drivers of the change, the vulnerabilities and adaptation strategies being used by the communities. The results of the study indicate that climate change impacts are decreasing the capability of the SRFR ecosystem to provide essential services to the communities. The principal livelihood sources affected by the climate change impacts are agriculture, forest resources and water resources. To minimize the impacts of climate change, the communities around the reserve have adopted various adaptation and coping strategies to improve agriculture, biodiversity conservation, and water resources management. The paper also suggests strategies that will enable policy-makers to effectively improve ecosystem services and climate change mitigation and adaptation in Ghana.

Keywords

Climate change; Ecosystem services; Forests; Livelihoods

Introduction

Climate change is arguably the greatest contemporary threat to ecosystems services, biodiversity and livelihood of poor forest fringe communities in developing countries. It is one of the most serious environmental, social and economic threats the world has ever faced [1-5]. It is real and happening faster than we previously thought with serious devastating impacts in developing countries, particularly on the Africa continent [1-3]. Its impacts are expected to deepen poverty, food insecurity, poor livelihoods and unsustainable development [3,6,7]. The poor countries in particular are the most vulnerable because of their high dependence on ecosystem services and their limited capacity to adapt to a changing climate [1,4,7-9].

Africa’s vulnerability to climate change is exacerbated by a number of non-climatic factors, including endemic poverty, hunger, high prevalence of disease, chronic conflicts, low levels of development and low adaptive capacity [9-11]. The most vulnerable sectors include agriculture, biodiversity, water, health, forests and energy. Many of the factors that make climate change unique also make it complex. According to Osbahr [12], it is a multi-scalar environmental and social problem, which affects different sectors. Vulnerability to the adverse impacts of climate change is among the most crucial concerns of many developing countries [13-14]. These impacts are often specific to individual sectors or regions, thus making some sectors and regions more vulnerable than others [7,15-17]. The main cause of climate change is the rising concentration of greenhouse gases (GHGs) in the atmosphere, which stem primarily from both natural and human activities [4]. The main GHGs are carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), principally from the burning of fossil fuels, forest destruction and agriculture and fluorocarbons, (CFCs) used in air conditioners and many industrial processes.

Climate change, ecosystem services and livelihoods

The link between climate change, ecosystems and livelihoods in most African countries has been well established [18-19]. An ecosystem is a complex system of plant, animal, fungal, and microorganism communities and their associated non-living environment interacting as an ecological unit [20,21]. Human well-being and progress towards sustainable development are vitally dependent upon the earth’s ecosystem services. They provide the foundation for all human survival, including a wide range of ecosystem services for improving livelihoods [22,23]. Ecosystems provide the human population a variety of goods and services such as food production, timber production, diseases control, climate change and air quality regulation, carbon sequestration, water quality and flow regulation, protection of habitats and biodiversity, tourism, flood control, cultural services, recreational, and as well as supporting services such as nutrient cycling that maintain the conditions for life on Earth.

In terms of livelihoods, the poor in particular have a unique and special relationship with ecosystems with regard to their livelihoods. Livelihoods involve a whole complex of factors that allow families to sustain themselves materially, emotionally, spiritually, and socially [22]. The declining productivity and deterioration of forest ecosystems is a central concern to millions of people whose livelihoods depend on them. The ability of ecosystem services to sustain agricultural production and improve incomes and food security of farmers is increasingly constrained in developing countries due to climate change impacts. Forest ecosystems particularly provide safety nets to poor communities for with regard to generation of income, food security, improvement of livelihoods and well being. Degradation of these ecosystem services would have adverse impacts on food accessibility, livelihood options and quality of life of local communities. In the absence of supportive mechanisms for acquiring basic needs of life in many developing countries, the degradation of forest ecosystems has often caused periodic phases of hunger and malnutrition.

Ecosystem services may be grouped into four broad categories: provisioning, such as the production of food, fresh water and fiber; regulating services such as biophysical processes that control climate, floods, diseases, air and water quality, and erosion; supporting, such as nutrient cycles and crop pollination; and cultural, such as spiritual and recreational benefits [8]. A change in an ecosystem has consequences for the supply of ecosystem services and livelihoods improvement. It can profoundly affect aspects of human well-being ranging from the rate of economic growth, health, food security, and livelihoods to the prevalence and persistence of poverty. Evidence in recent decades of escalating human impacts on ecological systems worldwide and climate change raise concerns about the consequences of ecosystem changes for human well-being and livelihoods of forest dependent communities [24]. Any progress achieved in addressing the goals of poverty and hunger eradication, improved health, and environmental protection may be unsustainable if most of the ecosystem services on which humanity relies continue to be degraded. Promoting a healthy functioning of ecosystems ensures the resilience of agriculture to meet the stress of growing demands for food production [25].

Overview of climate change and impacts in ghana

On a global scale, Ghana is a very small emitter of Greenhouse Gases (GHG) and will continue to be so compared to other emitters. Until 1996, Ghana was a net greenhouse gas sink with a per capita removal capacity of -2.3x10-4 Gg carbon dioxide (CO2) equivalent [26]. However, the carbon sinks capacity decreased by 400% between 1990 and 1996 [27]. Historical climate data observed by the Ghana Meteorological Agency across the country between 1960 and 2000 shows a progressive and discernible rise in temperature and a concomitant decrease in rainfall in all agro-ecological zones of the country [26-28]. Recorded temperatures rose about 1°C over the last 40 years of the twentieth century, while rainfall and runoff decreased respectively by approximately 20 and 30 percent [26]. Future climate change scenarios developed based on forty years of observed data, also indicate that temperature will continue to rise by about 0.6°C, 2.0°C and 3.9°C on the average by the year 2020, 2050 and 2080 respectively in all agro-ecological zones in Ghana. Rainfall is also predicted to decrease on average by 2.8%, 10.9% and 18.6% by 2020, 2050 and 2080 respectively in all agro-ecological zones [27].

There is enough scientific evidence to prove that the potential negative impacts of climate change are immense. Ghana is particularly vulnerable due to structural difficulties and lack of capacity to introduce adaptive measures to address environmental problems and socioeconomic costs of climate change [26,27]. Ghana is highly vulnerable to the various manifestations of climate change. National vulnerability assessments by EPA [26] have established negative impacts around critical human security sectors such as agriculture, fisheries, water resources, land, health and energy. Kuuzegh [27], notes that areas of the economy and sectors that are particularly important and adversely affected include water resources, especially in internationally-shared basins where there is a potential for conflict and a need for regional co-ordination in water management, threat to energy security through hydropower generation and impacts on fisheries, agriculture, food insecurity resulting from declines in agricultural production because of declining soil fertility, natural resources productivity, biodiversity and water resources that might be irreversibly lost. Also affected are human health due to increased incidences of vector and water and air-borne diseases, especially in communities with inadequate health infrastructure.

Research Problem, Objectives and Guiding Hypothesis

The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2005) reports that 60 to 70% of the world’s ecosystem services are

deteriorating, with dramatic consequences for forest dependent communities. Climate change is projected to exacerbate these threats and the livelihoods of forest dependent communities. In Ghana, the impacts of climate changes are already being experienced by communities around forest ecosystems including the SRFR in the Sefwi Wiawso District in the Western Region. Climate change projections also indicate greater vulnerability of forest communities to changing climate with regard to ecosystem services, livelihoods and access to food [26]. The livelihoods of the communities surrounding the reserve are very intimately linked to the availability of ecosystem services. Ecosystem services provision and other environmental resources such as non-timber forest products (NTFPs) have been the bedrock of livelihoods of the populations around the SRFR.

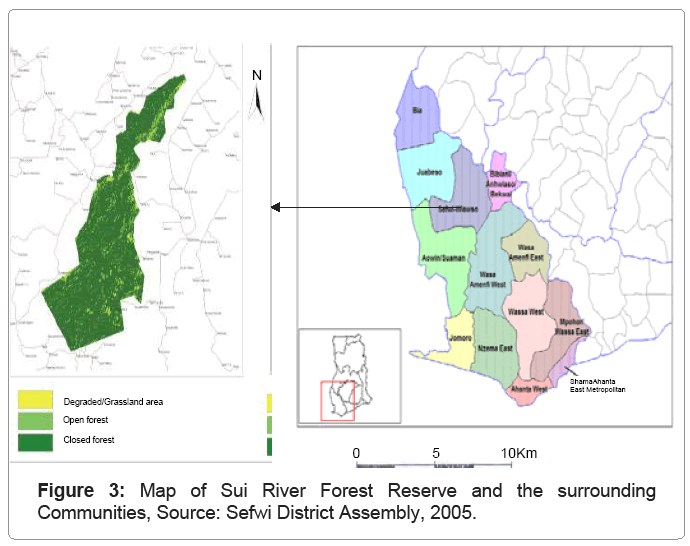

Designated in 1930 with an area of 311.36 km2, SRFR is of great importance to thousands of people in the Sefwi Wiawso District whose livelihoods largely depend on it. The reserve’s ecosystem also regulates the local and the district’s weather through its absorption and creation of rainfall and exchange of atmospheric gases. Unfortunately, climate change impacts triggered by human activities are reducing the capability of the ecosystem to provide ecosystem services to the communities. The reserve is also losing its closed forests at an alarming rate. Deforestation and degradation of SRFR ecosystem services have increased rapidly in the past few decades and is affecting the sources of livelihoods of the communities, especially cash and food crops production and NTFPs. It is estimated that the reserve has been reduced to less than 70% of its original closed forest between 1990 and 2000 Akrasi [29], and continues to reduce at an alarming rate annually.

The communities surrounding the reserve are particularly very vulnerable to the changing climate and ecosystem degradation because of limited capacity to adapt to the impacts of these changes. Experts have predicted that the warming and change in rainfall pattern around the reserve could impact the food production, availability and the livelihoods of the local communities and the district as a whole. While there is some evidence of climate change and its impact in the area, no comprehensive study has yet been conducted to determine the extent of these impacts on the SRFR ecosystem and the livelihoods of the communities, and the adaptation measures practiced by the people around the reserve. To enhance ecosystem services provision and improve the livelihood of the communities around the reserve, this paper has investigated and analysed the impacts of climate change on the ecosystem goods, services and the livelihoods of the communities. It identifies the main drivers of the change and evaluates the mitigating and coping strategies practised by the people around the forest reserve.

Approach and conceptual framework

To ensure a balanced understanding of the complex link between climate change, ecosystem services and livelihoods, the study adopted a Human Ecological Approach (HEA) which refers to the study of the dynamic interrelationships between human populations and the physical, biotic, cultural and social characteristics of their environment and the biosphere [30]. Human ecology is an interdisciplinary subject that integrates concepts across different disciplines and uses a holistic approach to solve problems and enhance the understanding of the complex interaction between human beings and their environments. The link between climate change, ecosystems and livelihood is complex, multifaceted and broader than the realm of any single discipline and can therefore be most effectively examined by using inter-disciplinary and multi-disciplinary frameworks. Knowledge from the disciplines in ecology, forestry, sociology, geography and economics are synthesized to enhance the understanding of this complex issue.

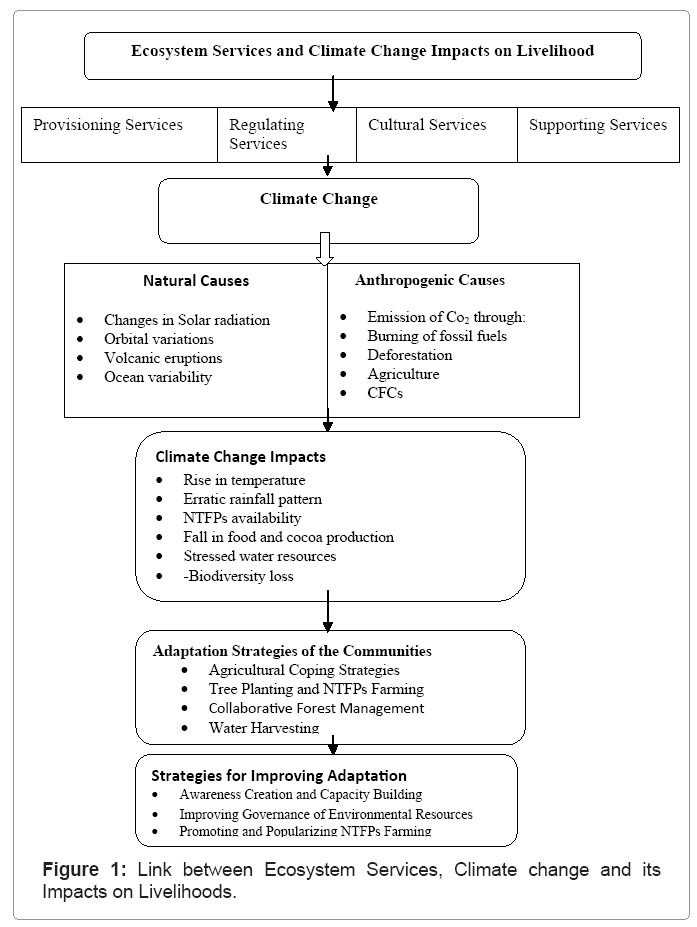

The conceptual framework on which this paper is anchored is the link between ecosystem services and livelihoods of forest dependent communities through their provisioning; regulating; supporting; and cultural and recreational services. The principal premise of the paper is that ecosystem services provide foundation for livelihoods and human wellbeing. A change in an ecosystem therefore, has consequences for the supply of ecosystem services and livelihoods improvement. The direct link between ecosystem services and livelihoods improvement and their role in maintaining and supporting the production of goods and services for human development is illustrated in Figure 1. The figure describes the relationship between various types of ecosystem services, their impact on livelihood improvement and human wellbeing as well as the principal human activities in and around SRFR. It also depicts the linkages between ecosystem services, the principal human activities, and the components of human well-being.

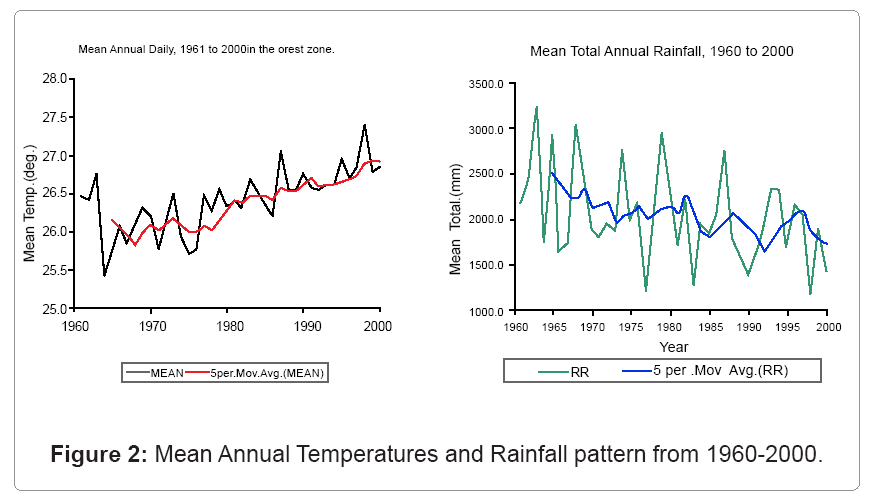

Climate change in the study area

Analysis of the climate data observed by the Ghana Meteorological Agency from 1960 to 2000 show a progressive and discernible rise in temperature and a corresponding decrease in rainfall in the forest zones of Western Region, including the Sefwi Wiawso District as depicted in (Figure 2). Recorded temperatures rose to about 1°C during the last 40 years of the twentieth century, while rainfall and runoff respectively decreased about 20 and 30%.

The data indicate high vulnerability among the most climate sensitive and critical livelihood systems particularly agriculture, human health, fresh water sources and biodiversity. Climate change projections also indicate that temperature will respectively continue to rise on average by about 0.6°C, 2.0°C and 3.9°C by the year 2020, 2050 and 2080 in all agro-ecological zones in Ghana. Rainfall is also predicted to decrease on average by 2.8%, 10.9% and 18.6% by 2020, 2050 and 2080 respectively in all agro-ecological zones. It is clear that the potential negative impacts of these changes will have devastating consequences for food security and livelihoods of the poor forest depeandent communities in the area.

Materials and Methods

Study area and description

The study is located in the Sefwi Wiawso District in the Western Region of Ghana. (Figure 3) shows the Map of Sefwi Wiawso and Sui River Forest Reserve

The vegetation of SRFR consists of the Celtic triplochiton association where some of the trees in the upper and middle layers of the forest shed their leaves usually in the dry season. The Sui River Forest Reserve falls within the tropical rainforest climatic zone, with warm temperatures throughout the year and moderate to heavy rainfall. The rainfall pattern is bimodal with maxima in May-June and September-October. Variation in monthly mean temperature is slight. The mean monthly maximum in the hottest month (February or March) is 31-33°C, and the monthly minimum in the coldest month August is 19-21°C. Since 1998, 105km2 of the forest reserve has been granted on concession to Suhuma Company Ltd for a period of 40 years. The common species in the reserve include: Strombosia glaucescens, Mahogany, Ceiba pentandra, Cylicodiscus gabunensis, Entandrophragma angolense, Copaifera, Antiaris toxicaria, Milicia excelsa, Entandrophragma utileand Triplochiton scleroxylon among others. The population around the reserve is mostly farmers.

Data collection

For this study, a systematic and integrated methodology was used to collect data for analysis. In addition to a comprehensive literature review, both secondary and primary data were collected and analysed. Secondary data on climate data for forty years (1960-2000) were collected from the Ghana Meteorological Agency (GMA). The data was used to examine the changes in the rainfall and temperature variability in the area over the period. In addition, a satellite image of the state of the SRFR reserve for the period (1990 and 2000) was obtained from the Resource Management Services Centre of the Forestry Commission in Kumasi to compare the changes in the Sui River Forest Reserve for the over a period of ten years. Secondary data on climate change, ecosystem services and livelihoods of the population in the district were obtained from the district directorates of Agriculture, Health, and Forestry as well as from the Environmental Protection Agency of Ghana (EPA). Consultations with the district health, agriculture, water and forestry officers also provided very useful information on climate change impacts and the mitigation and adaptation strategies being used by the communities’ around the reserve.

To enhance a broader understanding of the problem, a field survey in the communities surrounding the SRFR was conducted between May 2009 and July 2010. Five participatory and exploratory research methods were used in conducting the field research. These included administration of questionnaires, key informant interviews, focus group discussion, field observations, and experts’ consultations. The questionnaire and the interviews assembled information on the communities’ knowledge and experiences of ecosystem services, awareness of climate change and its impacts, livelihoods, vulnerabilities and coping and adaptation strategies. A total of 240 respondents from eight out of 15 communities around the reserve were selected through purposive sampling technique to participate in the survey. The communities included Sui, Sui Nkwanta, Kama, Nkonya, Ahenbenso, Apratu, Puakrom and Yawkrom. Only community members who were over 30 years and above were interviewed on the assumption that younger people have less experience on climate change impacts. A focus group discussion was organised in May 2010 to gather information about climate change impacts, ecosystem services and vulnerability of the local livelihoods to increased climate variability and change and degradation of ecosystem services. From the focus group discussions and questionnaires, individuals who showed appreciable knowledge of environmental changes around them were selected for in-depth interviews. They were mainly local farmers and key informants who could attest to noticeable changes in rainfall and temperature, and traditional and leaders involved in community decision-making. In addition, data on cocoa production trend between 1990 and 2010 data was collected from the Sui cocoa purchasing station.

Results and Discussion

This section analyses the results of climate change in the area, communities’ knowledge and experiences of ecosystem services, awareness of climate change, impacts on vulnerabilities and livelihoods, biodiversity, water resources and adaptation strategies. As was indicated in section 3.2, a total of 240 respondents participated in the field survey, the age distribution of the respondents ranges between 30 and over 60 years. About 35% of the respondents were between the ages of 30 and 50 years whilst 65% were aged 51 to 60 years. Out of the 240 respondents, 65.5% were married, 21.5% single, 8.5% divorced and 4.5% widowed.

Knowledge and experiences of ecosystem services

Ecosystem goods and services contribute significantly to the daily requirements of the communities either through their direct contact with ecosystem goods and services. The respondents identified some ecosystem goods and services which are very important to the populations as presented in (Table 1).

| Provisioning Goods | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Foods | Medicine | Other Goods | |

| Bush meat | Barks | Woodfuel | |

| Fresh water | Leaves | Timber | |

| Fish | Fruits | Mats | |

| Fruits | Animal products | Wooden trays | |

| Honey | Prepared tonics | Grinders | |

| Mushrooms | Hides | Mortars | |

| Snails | Seed | Pestles | |

| Spices | Roots | Chewing sticks | |

| Cola nuts | Essential oils | ||

| Regulating Services | Cultural | ||

| Air quality regulation | Spiritual and religious values | ||

| Local Climate regulation | Recreation | ||

| Erosion regulation | Libation | ||

| Water purification | Royal burial grounds | ||

| Pest regulation | Habitats for gods | ||

| Pollination | |||

| Food control | |||

Table 1: Ecosystem goods and Services identified by the communities.

With regard to the understanding of the population about ecosystems and their services, 85% of the respondents are aware of ecosystems and the importance of their services to the communities as indicated in (Table 2). Food production was ranked highest (34.5%) as the most important benefits derived from the forest ecosystem services followed by cocoa production (32.5%); NTFPs (15%); climate regulation and protection of river sources (10%), construction materials (7.5%) while eco-tourism was ranked the least important (0.5%).

| Ecosystem Services | % |

|---|---|

| Food production | 34.5 |

| Cocoa production | 32.5 |

| NTFPs | 15.0 |

| Climate regulation and protection of river sources | 10.0 |

| Construction materials | 0.5 |

| Total | 100 |

Table 2: Importance of Ecosystem Services.

Main livelihood activities of the communities: About 80% of the population in the communities surrounding the reserve is involved in agriculture, particularly, cocoa, maize, oil palm, cassava and plantain production. However, cocoa production is dominated by men while 80% of the women are involved in food crop production. Cocoa and food production are important elements of livelihood strategies amongst population in the study area. With the exception of cocoa, most farmers grow crops primarily for home consumption. Although most farmers have diverse sources of food for the households, NTFPs contribute about 35% of food sources. In some instances the cash income from the sale of NTFPs such as honey, nuts, fruits, bush meat, medicinal plants and snails provide them with the only source of personal income.

Awareness of climate change and its impacts: Although most of the farmers do not understand the science of climate change, their observations on the effects of decreasing rainfall, increasing air temperature, increasing sunshine intensity and seasonal changes in rainfall patterns is very impressive. The majority (78%) of the respondents are aware of climate change issues. Climate change is perceived in terms of changes in rainfall pattern and prolonged dry seasons which have characterized the area during the past 20 years. As regards the causes of climate change, 75% cited human activities such as inappropriate farming methods, bushfires and over-logging as the causes of climate change, whiles 25% attributed the phenomenon to natural occurrences, punishment by God for the sins of mankind and a sign of the end of the world as predicted in the bible. In terms of the severity of climate change impacts, agriculture is suffering most followed by forestry, biodiversity and fresh water sources.

Climate change impacts on vulnerabilities and livelihoods of the communities

Many factors underscore the vulnerability of the communities to climate change impacts. One notable result is that the livelihoods of the poor majority in the communities are highly dependent on climate-sensitive sectors such as agriculture, forest and water resources. The communities depend on forests resources, fuelwood, food security, water supply, NTFPs and medicinal plants for their primary healthcare. These livelihoods are also likely to be more vulnerable under the changing climate since both production systems and forests, which are a vitally important part of their livelihoods, are intricately dependent on the climate system. The changing climate has impacted negatively on ecosystem services, vulnerabilities and the livelihoods of the SRFR fringe communities. Perhaps the most affected livelihood sources of the communities is agriculture, particularly cocoa and food crop production, biodiversity and water resources. The most important climatic variable in terms of agricultural production in the study area is rainfall. The amount and distribution of rainfall partly determine which crops can be grown. As indicated earlier, over 80 percent of the population in the area depends on agriculture for their livelihood. Agriculture is mostly subsistence in nature with a high dependence on rainfall. The area has experienced a general reduction of precipitation over the past 30 years; this is attributed to climate change. These changes have had direct and indirect impacts on agriculture productivity in the district as a whole, especially cocoa and food crops production. Statistics collected from the cocoa purchasing station at Sui and consultations with cocoa purchasing clerks in Sui reveal a significant and consistent reduction in the production of cocoa between 1990 and 2009 due to consistent reduction in rainfall pattern and high temperatures and prolong droughts which have caused most cocoa trees to die. (Table 3) depict the trend in cocoa production in the Sui community between 1990 and 2009.

| Year | Tons | Year | Tons |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 118 | 2000 | 109 |

| 1991 | 116 | 2001 | 97 |

| 1992 | 116 | 2002 | 98 |

| 1993 | 112 | 2003 | 97 |

| 1994 | 111 | 2004 | 95 |

| 1995 | 105 | 2005 | 97 |

| 1996 | 109 | 2006 | 72 |

| 1997 | 105 | 2007 | 64 |

| 1998 | 105 | 2008 | 64 |

| 1999 | 105 | 2009 | 62 |

Table 3: Trend of Cocoa Production at Sui (1990-2010).

For instance, in 1990 a total of 118 tons of cocoa were purchased but in 2009 only 62 tons were recorded, implying a reduction of about 50%. Over the last 30 years, cocoa farms around the SRFR area are noted for high incidence of black pod disease which attacks the developing or ripening cocoa pods. This disease is significantly influence by weather and climate variability. For example, it is more prevalent in damp situations and is most destructive in years when the short dry period from July to August is very wet. The period between July and August has been very wet during the past 30 years instead of the hitherto short dry period which enables cocoa pods to develop well. Also, over 50% of cocoa farms in the area are over 40 years and needs replanting. Various attempts to replant most of the farms have failed due to prolonged dry seasons and high cocoa seedling mortality caused by erratic rainfall patterns. Climate change is also altering the stages and rates of development of cocoa pests and pathogens and host resistance and physiology of host-pathogen/pests interaction. High incidences of bushfires due to prolonged drought seasons have also destroyed some cocoa farms in the area. Consultations with five agricultural extension officers in the district corroborated the impact of the changing weather variability on production. An increasing temperature, erratic rainfall and prolonged drought conditions are expected to stretch SRFR ecosystem. This would constitute additional burden on poverty, diseases, weak institutional capacity and poor infrastructure at the district. Improving the adaptive capacity of forest-dependent communities is important in order to reduce their vulnerability to the effects of climate change.

Habitat destruction and biodiversity loss

Climate change is one of the major driver of habitat destruction and biodiversity loss in SRFR as a result of frequent bush fires due to high temperatures and prolong droughts. The problem is compounded by bush fires, illegal and unsustainable logging and hunting practices. The rapid increase in population due to an influx of migrant farmers to the communities is compounding the problem. Bush-meat hunting which is an important source of protein for the rural population in the communities is also one of the greatest threats to biodiversity. Poverty is real menace to biodiversity loss in the district. The continuous degradation of the reserve will result in significant biodiversity loss, including the extinction of many species and the associated loss of ecosystem services provision.

Impact on water resources

Climate change in Sefwi Wiawso District is already affecting water resources in terms of quantity, availability and intensity of precipitation. The most affected are the communities that depend on streams and rivers for their water needs. About 70% of the communities around the SRFR are without pipe borne water and boreholes. Streams and rivers which constitute the principal source of drinking water are unreliable because of less precipitation, deforestation and prolonged dry seasons. Some of the rivers that use to flow throughout the year in the communities get dried up during the dry seasons in recent years. For instance, the Sui River which has been the main source of drinking water to most of the communities around the reserve these days dries up during the dry seasons. The shortage of water resources has compelled some communities to resort to drinking water from polluted sources. The prevalence of diseases such as typhoid and diarrhea in the communities, especially Sui, is a major consequence. In some communities women and children have to travel long distances to fetch water. An analysis of most of these streams by the Community Water and Sanitation Agency indicate they are unsafe for human consumption and account for about 50% of environmental related diseases in the district [31].

Adaptation to climate change impacts and livelihoods improvement strategies

As it has already been emphasized, Sui and the surrounding communities are extremely vulnerable to climate change impacts because the area depends mainly on rain-fed agriculture. The field survey revealed that the communities use various adaptation and coping strategies in agriculture, biodiversity conservation, water resources management to minimize the impact of climate on their livelihoods. These strategies identified by the study are described below.

Agricultural coping strategies

One of the important agricultural coping strategies is the cultivation of crops that have shorter gestation periods and are drought resistant. Interviews with farmers and agricultural extension officers and field observations indicate that farmers are cultivating a variety of improved hybrids of cocoa (Mutant hybrids), maize, cassava and cereals that have shorter gestation periods and thrive well under the current prevailing climatic conditions. The high-yielding and drought resistance maize varieties include (Aburohemaa, Abontem and Enii-pii) whiles cassava varieties include Otuhia, Sika Bankye and Bankye Broni among others).

Tree planting and ntfps farming

Planting of economic trees and adopting sustainable farming systems were also identified as important coping strategies by 42.5% of the farmers. Through capacity building and sensitisation programmes, most farmers have recognised the importance of planting economic trees on their farms to shade their crops and NTFPs from intense sunshine and storms. Farmers are also engaged in planting commercial timber species as a livelihood strategy. Recognizing that the practice of harvesting NTFPs from natural forests is not sustainable since the products are getting depleted from the forest, farmers have started domesticating their production to supplement their incomes and cushion them against poor cocoa harvests in the future. Fifteen percent of the respondents are engaged in the farming of NTFPs such as beekeeping, mushroom production, grass-cutter farming and snail rearing. The cultivation of medicinal plants was also identified as an effective climate change adaptation strategy. These products contribute substantially to improve nutrition and household food security.

Collaborative forest management

Another important adaptation strategy introduced by the government to minimize the impacts of climate change and improve livelihoods in the communities is collaborative forest management (CFM). Until recently, local communities who have direct contact with forests and depend on them for their livelihoods were not involved in their management. Consequently, most local communities were not interested in taking measures to ensure a sustainable management of forest ecosystem. In recent years, the government has realised that climate change adaptation strategies that are based on the principles of sustainable forest management are likely to effectively promote an active participation of local communities in the conservation of environmental resources and improve their livelihoods.

CFM currently being practiced in forest fringe communities is the improved “Taungya System” in which farmers are given parcels of degraded forest reserves to produce food crops and to help establish and maintain timber trees. The objective is to produce a mature crop of commercial timber species in a relatively short time, address the shortage of farmland and poor soils in communities bordering the reserve and mitigate and/or reduce climate change impacts. The benefits of this approach are enormous. For example, food crops such as plantain, cocoyam and vegetables, are inter-planted with specific tree species. The food crops are normally cultivated for three years, after which the shade from the trees impeded further cultivation of the crops. In the improved taungya system, farmers are essentially the owners of forest plantation products, with the Forestry Commission, landowners and forest-adjacent communities as shareholders. They are eligible for 25% share of the benefits accruing from the plantation. The system ensures a continuous flow of benefits to participating farmers after the harvest of food crops at the end of the third year and a bulk payment at the time of harvesting of logs. This approach to forest management has provided sufficient security for farmers to invest in sustainable tree plantations. However, Agyeman [32] note that despite the intent of the strategy, there is the need for legislation to guarantee these rights and to ensure an equitable flow of benefits to landowners and local communities and their active involvement in making decisions to influence sustainable resource utilisation and management. The formation of Land Allocation and Taungya Management Committees at the local community level will also help to ensure that forest officers and farmers consult each other and coordinate their efforts to address the major challenges and impediments to an effective implementation of the system and create a win-win situation.

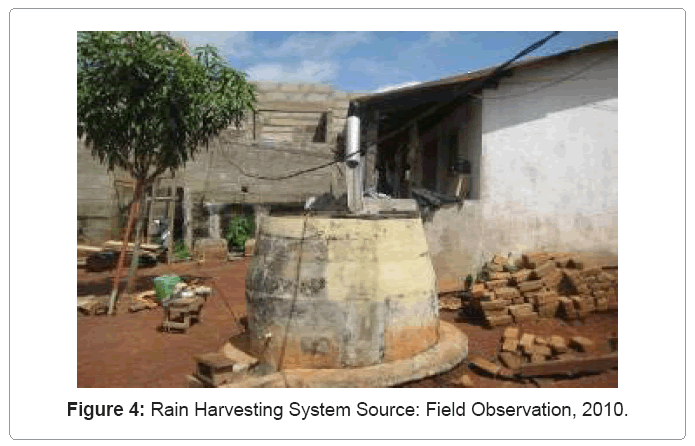

Water harvesting

Traditional water harvesting and treatment is a coping strategy for mitigate the impact of water shortage some communities. Realising that water shortage is a major threat to their survival, some farmers in the surveyed communities have developed several strategies to adapt to the situation by harvesting rainwater using a traditional methods and storing it in big barrels and tanks placed under the roofs of houses. Figure 4 shows rain harvesting technique used in some of the communities. This practice is however inefficient and unsustainable. There is the need to improve the capacity of farmers in modern and sustainable water harvesting and storage techniques.

Strategies for Improving Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation

Adaptation strategies being practised by the communities may however be inadequate to deal with the speed and scale of projected climate change. The following adaptation and mitigation strategies are therefore suggested to mitigate and minimize the impacts of climate change.

Mitigation measures

Climate change mitigation policy formulation: Climate change adaptation calls for comprehensive policy making [33]. Strategies for enhancing ecosystem services and mitigating climate change impacts require a clear climate change policy. Although various climate change protocols have been ratified in Ghana, mainstreaming climate change mitigation and adaptation into the existing decentralized governance system has not been effective. There is a lack of clear government policy on climate change mitigation and adaptation. Specific policies to encourage tree planting and maintenance are not clear and communities are not adequately informed about the rights of and benefits to farmers. Adaptation measures and policies should be developed with the full participation of local communities and other stakeholders to deepen their understanding of the relationship between human beings and the environment.

Afforestation and reforestation: Forest plantation programs focusing on equitable benefit sharing will ultimately help to improve ecosystem services and mitigate the impacts of climate change. Community-based action plans should be prepared on a yearly basis so that local people could initiate environmentally friendly activities and by planting trees in their farms. Forest restoration through re-forestation can help to remove greenhouse gasses from the atmosphere (carbon sequestration) and also promote poverty alleviation, biodiversity conservation and improvement of ecosystem services provision. There is the need to take advantage of initiatives such as payment for ecosystem services (PES) to encourage farmers and community members to plant more trees to enhance ecosystem services so as to mitigate climate change.

Improving climate change impacts adaptation

Awareness creation and capacity building: There is the need for continuous education and awareness creation on climate change mitigation and adaptation mechanisms in the communities surrounding SRFR. Raising awareness and building the capacity of communities around the reserve are vital tools for improving their understanding of the concept of climate change, its impacts and the capacity of the communities to effectively manage forest ecosystems and improve their livelihoods on sustainable basis. The communities’ appreciation of the ecological, economic and cultural values of the reserve will thus be enhanced. Improving human and institutional capacity of forest-sector institutions is crucial to ensuring climate change impacts mitigation and adaptation. To improve community adaptive capacity and resilience building mechanisms, the strategies should be reflected in the development and implementation of district and national climate change adaptation policies and strategies. Local authorities must ensure institutional collaboration and also prioritize adaptation efforts in communities where vulnerabilities are highest and where the need for safety and resilience is greatest so as to protect lives and livelihoods, promote development, improve safety and build adequate resilience.

Improving governance of environmental resources: Improving governance and active participation of local communities in environmental decision making is very important to improve ecosystem services management, improving adaptation and improve livelihoods. Conservation and proper management of forests and ecosystem services is not possible without an active participation by the local communities. Community engagement will contribute to improving climate change policy outcomes by assisting community members to develop informed understanding of climate change trends, impacts, consequences and maximising opportunities for citizens and communities to effectively contribute to public debate on climate change issues and actions. To achieve these goals, the Sefwi Wiawso District Forest Services Division needs to facilitate an active engagement of forest fringe communities in the protection and management of ecosystem services.

Promoting and popularizing ntfps farming: To improve the adaptation, resilience and capacity of forest communities, it is also important that forest stakeholders promote and popularize the domestication of NTFPs amongst forest dependent communities. The impacts of climate change are affecting the availability of these products which serve as safety nets during lean seasons. Enhancing forest-based livelihoods would be better achieved if foresters and policy-makers optimize NTFPs by promoting their domestication. This will significantly help conserve plant and animal species and improve the livelihoods of forest dependent communities.

Conclusion

Climate change is one of the greatest environmental, social and economic threats to the livelihood of forest dependent communities in developing countries. The impacts of climate change on ecosystem services and the livelihood of communities surrounding the SRFR have been identified in this paper. These communities are very vulnerable due to their high dependence on ecosystem services and their low capacity to climate change impacts. Sectors that are adversely affected by climate change include agriculture, biodiversity, and water resources. These impacts are most likely to deepen poverty, food insecurity and the poor livelihoods of the communities. To address these negative impacts, the communities have adapted various adaptation strategies in agriculture, biodiversity conservation, and water resources management to minimize climate change impacts. To improve ecosystem services, adaptation to climate change impacts, the resilience and capacity of the local communities, it is important to put in place appropriate mitigation and adaptation strategies.

References

- United Nations Environment Programme (2009) Environment for development, climate and trade policies in a post-2012 World. United Nations Environment Programme, Geneva, Switzerland.

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (2009) Adapting to climate change: towards a european framework for action. Commission of the European Communities.

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) (2008) Climate Change Mitigation: what do we do? OECD

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2007) Climate change 2007, Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. Contribution of working group II to the fourth assessment report of the IPCC, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK,

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (2006) Background paper on impacts, vulnerability and adaptation to climate change in Africa for the African Workshop on Adaptation Implementation of Decision 1/CP.10 of the UNFCCC, Accra, Ghana.

- Bo L, Erika SS, Ian B, Elizabeth M, Saleemul H (2004) Adaptation Policy Frameworks for Climate Change. Developing Strategies, Policies and Measures. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge, UK.

- 31st Session of the Committee on World Food Security (2005) Impact of climate change, pests and diseases on food security and poverty reduction, Food and Agriculture Organization.

- World Resources Institute (WRI) (2007) Restoring Nature’s Capital: An Action Agenda to Sustain Ecosystem Services. World Resources Institute, Washington DC.

- Desanker PV (2002) Impacts of climate change in Africa. WWF Climate Change Programme, Berlin, Germany.

- Food and Agricultural Organization (2009) Climate change adaptation, FAO, Rome, 1-19.

- United Nations Environment Programme (2002) Africa Environment Outlook: Past, Present and Future Perspectives. United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi, Kenya.

- Fighting climate change:Human solidarity in a divided world (2007) Building resilience: Adaptation mechanisms and mainstreaming for the poor. Human Development Report Office

- Climate Change andDevelopment (2001) Climate change and sustainable development strategies in the making: what should West African countries expect? Environnement et Développement du Tiers Monde.

- Salinger J, Sivakumar MV, Motha RP (2005) Increasing Climate Variability and Change: Reducing the Vulnerability of Agriculture and Forestry. Climatic Change 70: 362

- Climate ChangeRisk and Vulnerability (2005) Promoting an efficient adaptation response in Australia, Australian Greenhouse Office, Department of the Environment and Heritage

- McCarthy JJ, Canziani OF, Leary NA, Dokken DJ, White KS (IPCC) (2001) Climate Change 2001: impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Contribution of working group II to the third assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

- Gregory PJ, Ingram JSI, Brklacich M (2005) Climate change and food security. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 360: 2139-2148.

- United Nations Environment Programme (2006) Africa Environment Outlook 2. Our Environment, Our Wealth. United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi, Kenya.

- Bass S, Roe D, Smith, J (2010) Look both ways: mainstreaming biodiversity and poverty reduction. International Institute for Environment and Development.

- Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) (2009) Sustainable Forest Management, Biodiversity and Livelihoods: A Good Practice Guide. Montreal.

- Bond I, Grieg-Gran M, Wertz-Kanounnikoff S, Hazlewood P, Wunder S, et al. (2009) Incentives to sustain forest ecosystem services: A review and lessons for REDD. International Institute for Environment and Development, London, UK.

- World Resources Institute (2005) The wealth of the poor: managing ecosystem to fight poverty. World Resources Institute, Washington DC USA.

- OECD Workshop on the Benefits of Climate Policy:Improving Information for Policy Makers (2003) Analysing changes in ecosystems for different levels of climate change, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Paris.

- Sokona Y, Denton F (2001) Climate Change Impacts: can Africa cope with the challenges? Climate Policy 1: 117-123.

- Food and Agriculture Organization (2008) Feeding the World. Sustainable Management of Natural Resources. Fact sheets, FAO, City New York.

- Environmental Protection Agency- Ghana (2000) Ghana’s initial national communication under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Accra, Ghana

- Kuuzegh R (2007) Ghana’s Experience at Integrating Climate Change Adaptation into National Planning. Presentation at the UN.

- Anim G J, Frimpong E B (2005) Vulnerability of agriculture to climate change- impact of climate change on cocoa production, Cocoa Research Institute of Ghana, New Tafo Akim 1-31

- Akrasi A (2003) The state of the forests in the Sefwi Wiawso District, paper presented at the forest resources creation capacity building workshop, Sefwi Wiawso 1-15

- Lawrence RJ (2003) Human Ecology and its applications. Landscape and Urban Planning 65: 31-40.

- Boon E, Ahenkan A, Ameyaw DK (2008) Human and environmental health linkages in ghana: a case study of Bibiani-Bekwai and Sefwi Wiawso Districts. GRIN Publishing, Munich

- Agyeman V K, Marfo KA, Kasanga KR, Danso E, Asare AB, et al. (2003) Revising the taungya plantation system: new revenue-sharing proposals from Ghana. FAO, Unasylva 54: 40-43

- Sajid MR, Jahedul H, Gerstrøm A, Manja HA (2010) Understanding climate change from below, addressing barriers from above: Practical experience and learning from a community-based adaptation project in Bangladesh.

Relevant Topics

- Aquatic Ecosystems

- Biodiversity

- Conservation Biology

- Coral Reef Ecology

- Distribution Aggregation

- Ecology and Migration of Animal

- Ecosystem Service

- Ecosystem-Level Measuring

- Endangered Species

- Environmental Tourism

- Forest Biome

- Lake Circulation

- Leaf Morphology

- Marine Conservation

- Marine Ecosystems

- Phytoplankton Abundance

- Population Dyanamics

- Semiarid Ecosystem Soil Properties

- Spatial Distribution

- Species Composition

- Species Rarity

- Sustainability Dynamics

- Sustainable Forest Management

- Tropical Aquaculture

- Tropical Ecosystems

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 23713

- [From(publication date):

June-2013 - Nov 30, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 17900

- PDF downloads : 5813