“Liking” Social Networking Sites – Use of Facebook as a Recruitment Tool in an Outbreak Investigation, The Netherlands, 2012

Received: 09-Apr-2013 / Accepted Date: 13-Jun-2013 / Published Date: 15-Jun-2013 DOI: 10.4172/2161-1165.1000123

Abstract

Social Networking Sites (SNSs) such as Facebook offer health researchers a novel means to reach and engage with the public. Following a mumps outbreak in a Dutch village after a Youth Club party organised via the Facebook Events facility, we used Facebook to recruit attendees to our outbreak investigation. After a poor response using traditional means of publicising the study, we opened a Facebook account under the study name, sent private messages about the study to all individuals invited to the party via the Facebook Event, and regularly posted the questionnaire web-link to the online notice boards (“Wall”) on the Youth Club and our own Facebook accounts. We concurrently incentivised participation using gift vouchers but only directly informed individuals who had responded “Yes” to the Event of the incentive. Participant numbers subsequently increased from ten to 60 (response ~60%). 80% of participants reported hearing about the study via Facebook. Although impossible to disentangle the effects of the active Facebook protocol and the incentive, Facebook offered a means of directly contacting attendees whilst avoiding advertising the incentive to non-attendees. SNSs can potentially make an important contribution to modern health research, and ethical codes of conduct should be updated to encompass their use.

Keywords: Social networks; Outbreaks; Recruitment; Facebook

159776Introduction

Social Networking Sites (SNSs) are web-based services that allow individuals to: (1) construct an online profile representing them, (2) make connections with friends’ profiles, (3) express their preferences for particular activities and (4) view, share, and communicate online material and messages with other network members. As is increasingly recognised, online Social Networking Sites (SNSs) offer great potential for public health professionals to reach out and engage with the community at large for several reasons [1,2]. Firstly, in countries with extensive internet access, SNS use is often widespread and growing in popularity in many countries. In the Netherlands, a country with one of the highest levels of internet access in the world 80% of people aged 18-35 report using a SNS on at least a monthly basis and almost 900,000 new users joined the popular SNS Facebook in the past six months [3-5]. Secondly, SNS users tend to access their accounts frequently. For example, half of Facebook’s users log into their accounts at least daily [6]. This accessibility is increasing with the advent of new technologies such as Smartphones and tablets, as users no longer have to be at a computer to log in to their accounts [7]. In September 2012 alone, Facebook reported 600 million users accessing the SNS using Facebook mobile products [6]. Thirdly, use of SNSs tends to be low-cost or free, offering cost-effective opportunities for public health agencies to set up their own presence on these sites [8].

In recent years, public health institutes and professionals have utilised SNSs for various purposes including health promotion and information distribution intervention delivery decreasing attrition in longitudinal studies and study recruitment through advertisements placed on SNSs [1,2,9-14]. However, the methods with which to use these sites most effectively to engage with the public are not yet well understood and the ways in which public health institutes are employing SNSs in their daily work are under-reported in the scientific literature [1,2,15,16]. There is therefore a need for public health professionals to describe how they have used SNSs in their work so that key factors for success may be identified [2,15]. Nonetheless, evidence is growing that active, two-way communication strategies tailored to the target audience are more effective than passive information distribution [1,2,16].

We recently had the opportunity to explore the use of SNSs in recruitment to an outbreak investigation. In March 2012, a mumps outbreak occurred in a Dutch village after a party at the local Youth Club which was attended by approximately 100 teenagers and young adults. Mumps disease is caused by a paramyxovirus infection and is characterised by acute swelling of the parotid and other salivary glands; although usually mild and self-limiting, severe complications such as orchitis, pancreatitis, meningitis and deafness can occur. Despite vaccination coverage with two doses of the Jeryl Lyn strain Measles- Mumps-Rubella (MMR) vaccine consistently exceeding 93% in the Netherlands several outbreaks in highly vaccinated populations have occurred recently, particularly amongst university students [17-20]. This has prompted a large research programme into the transmission dynamics of mumps in the Netherlands. The outbreak in question offered a unique opportunity to investigate mumps transmission in a somewhat younger population as had been seen in earlier outbreaks. We set out to investigate the outbreak by means of a retrospective cohort study, aiming to identify risk factors for mumps and reasons for vaccine failure. Unfortunately, no guest list was available; The Youth Club did, however, have an active online presence, with its own website and Youth Club-specific Twitter, Facebook and Hyves (a Dutch SNS similar to Facebook) accounts, and the party had been organised using a Facebook Event amongst other communication tools. These online resources provided us with a potential means of reaching and contacting party attendees in order to recruit them to the study. As this was the first time the Municipal Health Service had used SNSs in the context of an outbreak investigation, a specific objective of our investigation was to trial the use of SNSs as a means of study recruitment within this population. This paper reports our experiences of this approach to study recruitment; the results of the epidemiological study are reported elsewhere.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using the online survey tool Questback® to collect data regarding history of illness (to identify mumps cases), demographics and, risk behaviours at the party (to identify potential risk factors for disease), and through which channels participants had heard of the study (to identify what advertising strategies had helped to recruit participants). The questionnaire was accessible on clicking a specific web-link. It did not require a password, and was live between 4 May 2012 and 4 June 2012, 2-3 months after the party. We were advised by the local Medical Ethics Assessment Committee, Nijmegen to consult existing ethical guidelines regarding public health research before conducting the study; these stated that specific ethical clearance was not required for questionnaire surveys investigating infectious disease outbreaks unless the questions were psychologically stressful or tiring; the participants would have to travel in order to participate; or participants would be asked questions on more than one occasion. There were no ethical guidelines regarding the use of social networking sites in health research.

Initial recruitment strategy

The study was advertised and publicised the questionnaire weblink via the following channels:

1) E-mail to Youth Club member list

2) Posting a message with the web-link on the Youth Club’s Facebook page

3) Posting a message with the web-link on the Youth Club’s Hyves page

4) Posting a message on the Youth Club’s own website

5) Tweeting the web-link from the Youth Club’s Twitter account

6) Press release in the local newspaper

7) Posters at the Youth Club

The Youth Club Chair was responsible the first five methods (webbased media) and the Municipal Health Service were responsible for the press release and poster. Only one e-mail was sent and only one Tweet/post placed on Facebook or Hyves, as the Chair had other time pressures and was unable to follow up with a more active campaign of engagement.

Initial response was low (10 participants on the first day of study implementation, followed by no new participants over the next ten days) and it proved difficult to motivate the Youth Club Chair to increase activities to improve recruitment (e.g. send reminder e-mails or re-post messages on SNSs). Therefore we adopted an enhanced recruitment strategy in an effort to increase participation.

Enhanced recruitment strategy

Incentive: Participation was incentivised so that all questionnaire respondents would receive a €10 gift voucher valid in many shops in the Netherlands.

Active facebook protocol

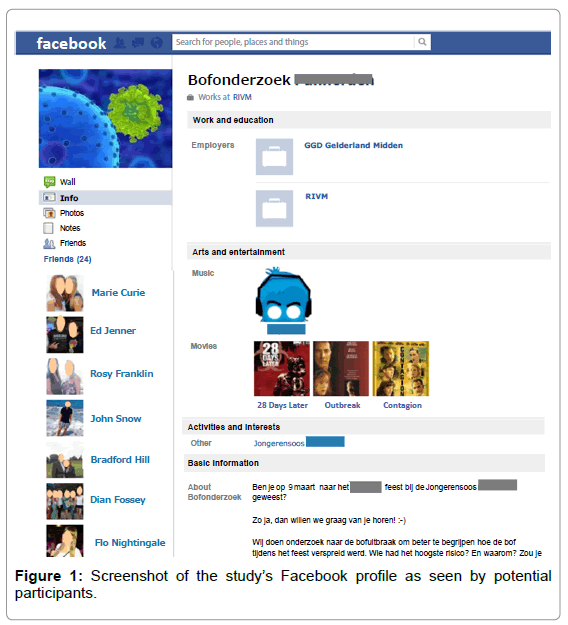

• Creation of account: We opened a Facebook account (“profile”) under the study name and introduced the study, its objectives and the questionnaire web-link in the “Basic Information” section of the account homepage, one of the first sections that a new visitor to the profile would see. In the “Basic Information” section we also directed visitors to two “Notes” pages on our profile, entitled “What is mumps?” and “What is the study about?” for more extensive information. We also invited potential participants to contact us via a specific e-mail address or using the Facebook private messages facility should they require further information. In order to personalise our profile, we uploaded a photo album of the researchers, and listed the following as things we “Liked” on our profile page: the Youth Club Facebook page; the DJ that performed at the party; and popular, mainstream films with an outbreak theme (such as 28 Days Later and Contagion). We set our privacy settings to “Public” so that any Facebook user could view all aspects of our profile. Figure 1 depicts how our profile page looked to a visitor.

• “Wall” posts: We regularly posted public messages about the study to our online notice board (“Wall”) and to the Youth Club’s Wall. These messages included the web-link to the questionnaire.

• Private messages: We sent private messages to all of the people on the Event list who had answered “Yes” or “Maybe” to the Event invitation, or who had not responded to the invitation. We did not send messages to people who had responded “No” to the invitation. These private messages were personalised using the recipient’s first name, and included some background information on the study and the web-link to the questionnaire. Recipients were asked to “Like” or “Share” the web-link or our Wall posts. In order to avoid people who had not attended the party completing the questionnaire purely for the incentive, we only included information about the incentive in the private message if the recipient had replied “Yes” to the Event invitation; otherwise, recipients only found out about the incentive once they had clicked the web-link.

• “Friend Requests”: If a study participant could be traced as a Facebook user (identified by first name and surname), and had given permission in the questionnaire to be contacted later by the researchers, we sent him or her “Friend Request”. This was for three purposes:

1. To Increase Accessibility to the Target Group – some Facebook users have privacy settings so that private messages can only be received from “Friends of Friends”. By “Friending” a study participant, we were consequently able to directly contact each of the participant’s Friends who had such privacy settings and were listed on the Event as invited to the party.

2. To Increase Visibility and Acceptability of the Study – accepting a Friend Request is advertised in a user’s “News Feed”, a running summary of what that user is doing. The News Feed is visible to the user’s Friends. Becoming Friends with a study participant would therefore further advertise the study among their friendship group, and possibly increase acceptability among their peers through publically acknowledging their connection with the study.

3. To Decrease Spam Blocking – as our Facebook profile was new and we were sending similar messages to many people at the same time, initially Facebook would interpret this activity as possible spam and periodically block the account. When other Facebook users accepted our Friend Requests, this verified that they recognised our profile as “real”, decreasing spam problems.

• Language: In order to create an informal and friendly tone appropriate for the SNS setting, we used informal language and terms such as smileys in all our communications. The content of these communications can be found in the Appendix.

Ethics

We were advised by the local Medical Ethics Assessment Committee, Nijmegen to consult existing ethical guidelines regarding public health research before conducting the study; these stated that for all age groups (including those under 18 years), specific ethical clearance was not required for questionnaire surveys investigating infectious disease outbreaks unless the questions were psychologically stressful or tiring; the participants would have to travel in order to participate; or participants would be asked questions on more than one occasion. Considering none of these applied to our intended study we did not pursue obtaining specific ethical clearance [21-23]. There is currently no national ethical guidance on using SNSs for public health research that could be consulted with regards the design and acceptability of the early tweets and posts or the later Active Facebook protocol. Therefore, we consulted with the Chair of the Youth Club board (a voluntary, peer-led organisation), who was enthusiastic about the Active Facebook protocol approach and did not foresee that it would be negatively perceived (indeed, he indicated that a message via Facebook would be perceived as less invasive than an email or telephone call).

Results

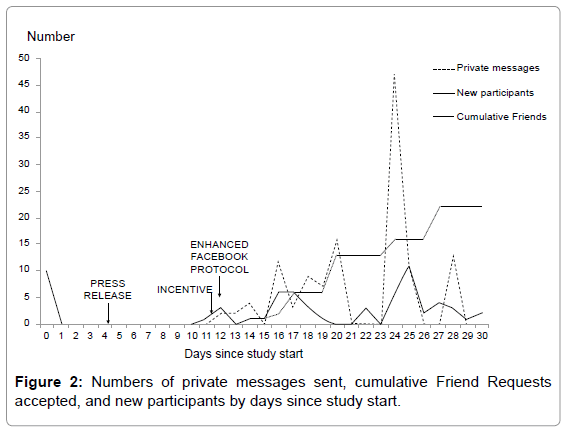

We sent private messages to 133 individuals listed on the Facebook Event invitee list asking them to join the study, with an additional 47 reminder messages. Following adoption of the enhanced recruitment strategy, participation rose from 10 to 60, an overall response rate of approximately 60%, given the estimated 100 people attending the party. Participants were aged 15-25 years, median 18 years, and 52% were male (n=31). Facebook was the most common channel through which participants heard about the study, with 80% of respondents reporting they had heard through the social networking site compared to the next most common channel, word of mouth, at 47% (Table 1). Numbers of new participants broadly mirrored the number of private messages sent out each day, with peaks in participation often seen on the same day as a peak in messaging (Figure 2). We received nine private Facebook messages in relation to the study from individuals contacted, and no e-mails. Of 35 Friend Requests, 22 (63%) were accepted. There were no Likes or shares of our Wall posts.

| Channel | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| 48 | 80 | |

| Word of mouth | 28 | 47 |

| Youth Club website | 14 | 23 |

| 13 | 22 | |

| 10 | 17 | |

| Newspaper | 10 | 17 |

| Hyves | 1 | 2 |

| Poster at Youth Club | 1 | 2 |

| Other | 3 | 5 |

| N=60 |

Table 1: Channels through which participants heard about the study.

Discussion

We report the use of Facebook to recruit participants to a retrospective cohort study aimed at investigating a mumps outbreak following a party. After an initial low response rate, we used the Facebook Event facility to identify members of the cohort, and set up our own Facebook profile to directly contact these individuals. We also introduced a gift voucher incentive for participation. Following the introduction of this active Facebook protocol and incentive, the response rate increased from 10% to 60%, sufficient to conduct an outbreak investigation. The majority of participants reported hearing about the study through Facebook. Potential participants contacted the study team for information via the Facebook private messaging facility rather than by e-mail.

To our knowledge this is the first description of specifically utilising a Facebook Event to recruit people to an outbreak investigation. However, other studies have reported using the Facebook Ads facility to recruit participants to public health research or using the SNS to locate and communicate with research subjects lost to follow-up in longitudinal studies [10-14]. Previous studies have also reported setting up their own study-specific Facebook profiles in order to give their research an online presence in the Facebook sphere [11,13]. Although we initially hoped to recruit participants to our investigation simply by posting generic messages about the study on various SNSs (Facebook, Hyves and Twitter), we found that response only increased after we adopted an active Facebook protocol and introduced an incentive: passive dissemination of the web-link was not sufficient. We opted to open a dedicated “Profile” rather than a Group or Page as it maximised the opportunities for direct communication with our targeted audience, and because we anticipated that a personalised Profile for our small research team would be perceived as less “institutional” and more “approachable” and “friendly” by our target audience, and thus perhaps more likely to increase the response. Our experience adds to growing evidence that the successful use of SNSs in public health requires active effort on the part of agencies and researchers, specifically tailoring messages and content to the intended audience and the SNS being used [1,2,16]. While the use of SNSs by hospitals and public health agencies is growing, the manner in which they are used is often very one-way, with a focus on passive dissemination of information rather than actual engagement [1,15].

Despite our requests, our posts about the study were not Liked or shared by anyone. Therefore, it was down to the researchers to ensure that the study became known to the target group. However, the accepted Friend Requests can be expected to have further publicised the study by appearing in those user’s News Feeds [24]. Although we were initially apprehensive about how potential participants would respond to being directly contacted through Facebook, the high response to Friend Requests suggest a good level of acceptability. Furthermore, the fact that all enquiries we received about the study were through Facebook messages rather than via an institutional e-mail account suggests that our target group was perhaps more comfortable to communicate through a SNS rather than more formal channels. SNSs are now part of many people’s daily reality, especially among younger populations, and similar positive responses amongst adolescents to being contacted through Facebook have been reported elsewhere [10]. As traditional recruitment methods are becoming more difficult and less successful methods to recruit individuals to research should evolve along with their target populations [11,25]. As we demonstrated, SNSs can be an effective platform to recruit participants. However, ethical aspects need consideration. Once a participant accepted our Friend Request, we gained access to a large amount of personal data published on their Facebook profiles. Although it could be argued that participants implicitly gave consent to our having access to personal data by accepting our Friend Request, they may have not fully appreciated that by doing so all their information posted on Facebook became available to the researchers and that by being Friends with our Facebook account, participants’ names were publically linked to the research. To minimise this, we restricted our account’s Privacy settings once the recruitment phase was over so that our account was not publically visible. Once the study was over, we deactivated the account. We recommend that such measures to deal with ethics and privacy issues in research that uses SNSs are written into study protocols prior to the implementation of the research. In addition, there is a need for national institutes to update legislation and guidelines to incorporate the use of the internet, and particularly SNSs, in health research. Currently, Dutch laws and codes of conduct for medical research (the data protection law the medical treatment law and the national Code of Conduct for Health Research [21-23] do not consider the use of SNSs for research purposes, and adaptation would be useful to address the ethical issues that arise. International, freely-available guidance does exist on the use of the internet in health research, such as the Recommendations from the Ethics Working Committee of the Association of Internet Researchers [26]. However, these do not address SNS use directly, and in any case are not bound by Dutch law.

A major limitation of our study is that we cannot disentangle the effect of the active Facebook protocol on increasing participation from the effect of the incentive, as both were introduced at the same time. Had the incentive been available from the outset, the initial response rate may have been far higher. However, Facebook did give us a useful means of only advertising the incentive to people who had very likely been at the party (i.e. those who had answered “Yes” to the Facebook Event invitation). We believe that had we had to announce the incentive globally, e.g. through an e-mail to all Youth Club members, the investigation results may have been disrupted by people who had not been at the party participating in the study purely to obtain the incentive. Therefore, although it is impossible to disentangle the effects of the active Facebook protocol and the incentive with regards the increase in participation, Facebook was a key facilitator in enabling us to offer an incentive in the first instance. A second limitation is that owing to the resources available, we only involved one SNS, Facebook, in the enhanced recruitment protocol. Therefore although Facebook was by far the most frequent channel through which participants heard about the study, no direct comparisons can be made between this and other SNS channels as considerably more effort was invested into Facebook. In future studies it would be of interest to involve all relevant SNSs in an enhanced protocol (e.g. setting up a Twitter account under the study name), in order to test which SNSs might have the widest reach or effectiveness. A third limitation is the relatively long delay (approximately two months) between the party and implementation of the study. This delay may have contributed to the initial low response, as interest in the outbreak may have waned by this point. Lastly, this investigation was amongst a young age-group, so this type of recruitment strategy may currently be less appropriate in older populations who may be less internet-active. Nonetheless, we must remember that this young generation will themselves become older and will in all likelihood continue to remain active SNS users, so that recruiting though SNSs will perhaps become progressively more valid. Furthermore, it is important to note that although SNS use is commonly portrayed as a teenage activity, this is increasingly not the case [27]. Indeed, in the Netherlands, the largest group of Facebook users are aged between 25 and 35 years, and in the past three months, the greatest growth in new users has been seen in those aged 25-54 years [5].

In conclusion, in our study, using Facebook allowed us to identity and directly contacts our target group, and helped to increase the response rate to a sufficient level to successfully conduct an outbreak investigation. As SNSs become ever more popular, providing the opportunity for wide-reach and low-cost engagement with the community, these novel tools should be considered a first-line means of study recruitment in public health practice and research. Although there remains much to learn about how best to use SNSs to engage effectively with the public, our experience adds to growing evidence that passive dissemination of information through SNS channels is insufficient. Instead, researchers should develop a strategic protocol for SNS communication at the outset, specifically tailored to the target audience and focused on engagement rather than information. Such protocols should incorporate advice from existing guidelines (whether national or international) on ethical decision-making in internet research in order to secure and maintain good levels of acceptability by the public.

Acknowledgements

We thank Suzan Trienekens and Jeroen Alblas at the RIVM for their input into developing the Facebook profile. We thank Ioannis Karagiannis of the European Programme for Intervention Epidemiology Training, Marianne van der Sande of the Dutch National Institute of Public Health and the Environment and the two anonymous reviewers for critical review of the manuscript. Finally, we thank all participants, without whom the study would not have been possible. The study was jointly funded by the Dutch National Institute for Public Health and the Environment and the Municipal Health Service Gelderland- Midden.

References

- Thackeray R, Neiger BL, Smith AK, Van Wagenen SB (2012) Adoption and use of social media among public health departments. BMC Public Health 12: 242.

- Gold J, Pedrana AE, Sacks-Davis R, Hellard ME, Chang S, et al. (2011) A systematic examination of the use of online social networking sites for sexual health promotion. BMC Public Health 11: 583.

- van Deursen AJAM, van Dijk JAGM (2010) Trendrapport Computer-en Internetgebruik 2010. Een Nederlands en Europees perspectief. Technical report, University of Twente, the Netherlands.

- Kaplan AM, Haenlein M (2010) Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social Media. Bus Horiz 53: 59-68

- Freeman B, Chapman S (2008) Gone viral? Heard the buzz? A guide for public health practitioners and researchers on how Web 2.0 can subvert advertising restrictions and spread health information. J Epidemiol Community Health 62: 778-782.

- Napolitano MA, Hayes S, Bennett GG, Ives A, Foster GD (2012) Using Facebook and Text Messaging to Deliver a Weight Loss Program to College Students. Obesity 21: 25-31

- Jones L, Saksvig BI, Grieser M, Young DR (2012) Recruiting adolescent girls into a follow-up study: benefits of using a social networking website. Contemp Clin Trials 33: 268-272.

- Mychasiuk R, Benzies K (2012) Facebook: an effective tool for participant retention in longitudinal research. Child Care Health Dev 38: 753-756.

- Ramo DE, Prochaska JJ (2012) Broad reach and targeted recruitment using Facebook for an online survey of young adult substance use. J Med Internet Res 14: e28.

- Richiardi L, Pivetta E, Merletti F (2012) Recruiting study participants through Facebook. Epidemiology 23: 175.

- Fenner Y, Garland SM, Moore EE, Jayasinghe Y, Fletcher A, et al. (2012) Web-based recruiting for health research using a social networking site: an exploratory study. J Med Internet Res 14: e20.

- Van de Belt TH, Berben SA, Samsom M, Engelen LJ, Schoonhoven L (2012) Use of social media by Western European hospitals: longitudinal study. J Med Internet Res 14: e61.

- Bennett GG, Glasgow RE (2009) The delivery of public health interventions via the Internet: actualizing their potential. Annu Rev Public Health 30: 273-292.

- van Lier EA, Oomen PJ, Giesbers H, Drijfhout IH, de Hoogh PAAM, et al. (2011) Vaccinatiegraad Rijksvaccinatieprogramma Nederland. Verslagjaar 2011. Bilthoven: National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM)

- Whelan J, van Binnendijk R, Greenland K, Fanoy E, Khargi M, et al. (2010) Ongoing mumps outbreak in a student population with high vaccination coverage, Netherlands, 2010. Euro Surveill 15.

- Brockhoff HJ, Mollema L, Sonder GJ, Postema CA, van Binnendijk RS, et al. (2010) Mumps outbreak in a highly vaccinated student population, The Netherlands, 2004. Vaccine 28: 2932-2936.

- Greenland K, Whelan J, Fanoy E, Borgert M, Hulshof K, et al. (2012) Mumps outbreak among vaccinated university students associated with a large party, the Netherlands, 2010. Vaccine 30: 4676-4680.

- The Medical Act Behandelingsovereenkomst (Dutch Medical Treatment Act) 1994

- Gedragscode voor gezondheidsonderzoek (Dutch Code of Conduct for Health Research) 2004

- Abdesslem FB, Parris I, Henderson TNH (2010) Mobile experience sampling: Reaching the parts of Facebook other methods cannot reach. Paper presented at 24th BCS Conference on Human Computer Interaction (HCI2010), Dundee, United Kingdom

- Morton LM, Cahill J, Hartge P (2006) Reporting participation in epidemiologic studies: a survey of practice. Am J Epidemiol 163: 197-203.

- Markham A (2012) Ethical decision-making and Internet research: Recommendations from the AOIR ethics working committee

- Corten R (2012) Composition and structure of a large online social network in The Netherlands. PLoS One 7: e34760.

Citation: Ladbury G, Ostendorf S, Waegemaekers T, Hahné S (2013) “Liking” Social Networking Sites – Use of Facebook as a Recruitment Tool in an Outbreak Investigation, The Netherlands, 2012. Epidemiol 3:123. DOI: 10.4172/2161-1165.1000123

Copyright: © 2013 Ladbury G, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 14841

- [From(publication date): 6-2013 - Dec 20, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 10080

- PDF downloads: 4761