A Complicated Case of Diaphragmatic Hernia Combined With Pyothorax

Received: 10-May-2024 / Manuscript No. DPO-24-134673 / Editor assigned: 13-May-2024 / PreQC No. DPO-24-134673 (PQ) / Reviewed: 29-May-2024 / QC No. DPO-24-134673 / Revised: 03-Jul-2025 / Manuscript No. DPO-24-134673 (R) / Published Date: 10-Jul-2025

Abstract

Background: Pyothorax and diaphragmatic hernia are both common and serious diseases, but pyothorax combined with diaphragmatic hernia is rare. Pyothorax can mask the clinical and Computed Tomography (CT) manifestations of diaphragmatic hernia, leading to diagnostic errors and thus delays in diagnosis, which may lead to the patient's death. We report a case of diaphragmatic hernia combined with pyothorax. The patient underwent a complicated treatment and was finally diagnosed and cured by surgery.

Case presentation: A 71-year-old woman who was admitted to the hospital with left-sided chest pain and an outof- hospital diagnosis of left-sided pleural effusion. After admission, she was diagnosed with left-sided pyothorax after Computed Tomography (CT) examination and puncture and tube placement and diaphragmatic hernia with pyothorax was considered after surgical treatment. The patient was cured by surgery and no recurrence was observed during follow-up.

Conclusion: Diaphragmatic hernia combined with pyothorax is an extremely rare and serious disease, even leading to death and early diagnosis is extremely important. Pyothorax masks the clinical and CT manifestations of diaphragmatic hernia, thus complicating the diagnosis. Although we know that it can be cured by surgical treatment, it is difficult to make a correct and risky treatment plan without a clear diagnosis. This type of case is rarely reported and we hope that reflection on this case can further improve the diagnostic ability of clinicians.

Keywords: Diaphragmatic hernia; Pyothorax; Enterococcus faecium; Candida glabrata

Introduction

Diaphragmatic hernias are categorized as congenital and active diaphragmatic hernias. About 70%-95% Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia (CDH) cases are diagnosed in the neonatal period and 5%-45.5% cases are diagnosed later in life. Pleural space infections have a considerable prevalence and remain a life-threatening condition, with up to 15% of patients requiring organ support in critical condition. Cases of diaphragmatic hernia combined with pyothorax are less frequently reported and we report a similar case [1].

Case Presentation

A 71-year-old woman, 10 days ago due to "left anterior thoracic pain with chest tightness after activity" in other hospitals, line fiberoptic bronchoscopy suggests that "the left lower lobe of the outer basal section of the mucous membrane is swollen, hypertrophied, lumen narrowing chest Computed Tomography (CT) showed inflammation of both lungs, medium volume of fluid in the left pleural cavity, cavity formation in the lower lobe of the left lung and the lung abscess was possible. Closed chest drainage of hemorrhagic pleural fluid, relieved after treatment. One day before admission, the patient gradually coughing sputum, white foamy, small amount, with fever, body temperature 37.7 degrees celsius, accompanied by decreased appetite. He was hospitalized in the department of respiratory medicine with a pulmonary infection [2].

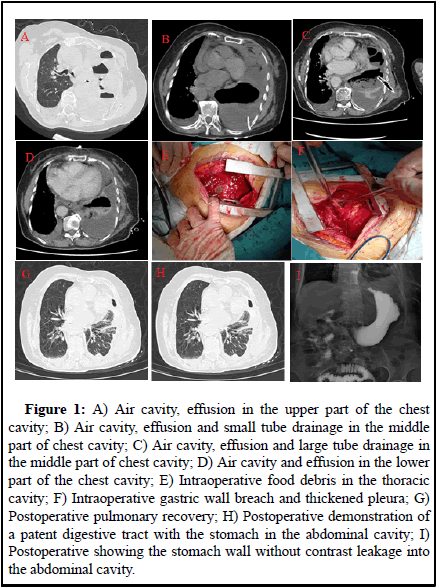

The left lung was turbid by percussion and the chest tube was unavailable. Computed Tomography (CT): Atelectasis of the left lung, structures in the left hilar region was poorly displayed and soft tissue shadows appeared to be seen in the hilar region. There was a large amount of fluid and air in the pleural cavity on the left side, with a drainage tube placed in it and there was a small amount of fluid in the pleural cavity on the right side. Pneumothorax changes on the right side. Small amount of pericardial effusion (Figure 1A, B). Blood count: Leukocytes 16.36 × 10/L, hemoglobin 105 g/L, neutrophil ratio 80.50%, lymphocyte ratio 8.10%, albumin 26.2 g/L, calcitonin 0.569 ngmL [3].

Diagnosis

• Left sided fluid pneumothorax

• Left hilar tumor?

• Pericardial treatment: anti-infection treatment was given after admission, placement of a large tube of closed chest drain (Figure 1C, D), a small amount of yellowish liquid was drained. Pathological diagnosis of pleural fluid: Found most of the inflammatory cells mainly neutrophil, did not see the exact tumour cells [4].

Thoracoscopy was performed, suggesting extensive dense adhesions in the thoracic cavity, which led to the cessation of exploration. The drug sensitivity culture of pleural fluid suggested Enterococcus faecium infection and the patient was transferred to our department. The patient developed hypoproteinemia, nutritional deficiency, anemia, weight loss and other complications. The patient's condition improved after being actively given anti-infective and nutritional supportive treatment. After repeated communication with the patient's family, he was prepared to undergo pyothorax removal with fibrous plate debridement [5].

During surgery, extensive adhesions were found in the right thoracic cavity, with thickening of the dirty pleura and the wall pleura, up to about 1 cm. Food debris was seen in the thoracic cavity (Figure 1E). There were multiple septate and encapsulated pus cavities. The diaphragm showed a 3 × 5 cm fissure and the gastric fundus entered the thoracic cavity and became embedded and ischemic necrosis. There were three necrotic perforations in the gastric wall of about 1 × 1 cm, 3 × 3 cm and 3 × 4 cm respectively (Figure 1F). Surgical method: Lung decortication+diaphragmatic repair+partial gastrectomy. Surgical incision: left posterior lateral sixth intercostal incision of about 20 cm. Chest pus culture showed Candida glabrata. Postoperatively, she was given parenteral nutrition, blood transfusion, anti-infection, correction of liver function, antifungal and symptomatic treatment. After surgery, her heart function failed, with positive treatment, her condition improved. She was discharged from the hospital 2 weeks after the operation (Figure 1G, H, I) [6].

Figure 1: A) Air cavity, effusion in the upper part of the chest cavity; B) Air cavity, effusion and small tube drainage in the middle part of chest cavity; C) Air cavity, effusion and large tube drainage in the middle part of chest cavity; D) Air cavity and effusion in the lower part of the chest cavity; E) Intraoperative food debris in the thoracic cavity; F) Intraoperative gastric wall breach and thickened pleura; G) Postoperative pulmonary recovery; H) Postoperative demonstration of a patent digestive tract with the stomach in the abdominal cavity; I) Postoperative showing the stomach wall without contrast leakage into the abdominal cavity.

Results and Discussion

Diaphragmatic hernia is a type of internal hernia, a disease state in which abdominal organs and other organs move ectopically through the diaphragm into the thoracic cavity. Generally, the protrusion of intra-abdominal organs into the thoracic cavity through a congenital defect of the diaphragm is called congenital diaphragmatic hernia and the entry into the thoracic cavity through an acquired fissure is called acquired diaphragmatic hernia. Pyothorax is an infection of the pleural cavity, which is categorized as acute, subacute or chronic pyothorax based on the duration of its infection. Cases of simple diaphragmatic hernia combined with necrosis have been reported more rarely and necrosis followed by pyothorax are particularly rare. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia causing gastric necrosis in combination with pyothorax has not been reported. Li reported a case of spontaneous septal hernia with gastric necrosis. Kajal reported a misdiagnosed case of advanced congenital diaphragmatic hernia with medical gastric perforation [7].

In our case we are not quite sure about the origin of the pyothorax, which may have resulted from contamination of gastric contents after gastric necrosis or may have been caused by medical gastric rupture after puncture placement. Combined with the relevant postoperative data we have several points to analyze. First, the patient from the clinical symptoms to the surgical treatment is about 17 days, intraoperatively found that the wall pleura thickening to about 1 cm, consider chronic pyothorax. Considering the time, it should be that the patient already had an abscess before he had clinical symptoms. Second, the patient's postoperative culture was considered Candida glabrata [8].

Cases of Candida glabrata leading to pyothorax often require concomitant high risk factors. The identified risk factors for the development of Candida glabrata include elderly age, underlying comorbidities (such as diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, cirrhosis, and malignancies), septic shock, receipt of steroids or chemotherapy, prolonged antibiotic use, ICU stay and intra-abdominal diseases (such as esophageal rupture, complicated surgery, pancreatitis, etc. In this case, the patient's gastric necrotic perforation can be considered as a high-risk factor and the concomitant infection with Enterococcus faecium is also compatible with the conditions of complex flora infection. It seems that it can be interpreted as a pyothorax resulting from the patient's gastric necrotic perforation. However, the time of onset and the clinical symptoms does not seem to be acceptable enough [9].

The patient was not clearly diagnosed preoperatively and several factors were analyzed. First, both pyothorax and septal hernia are common clinical diseases, but pyothorax combined with septal hernia is rare clinically. Secondly, the patient had chest pain, fever and other symptoms and several times CT suggested pleural effusion and pleural drainage tube with pleural fluid drainage and hematological examination of infection index was elevated, which led to the clinical thinking more inclined to the diagnosis of infectious diseases. Third, the patient had no history of trauma, which led to the clinical thinking of the condition without considering trauma-related diseases. Fourth, the preoperative CT image considered the left pleural effusion and gas and the clinic thought more about the septic pneumothorax and did not consider the gas area to be the gastric bubble area, and the chest tube was containing a yellowish liquid and no food residue was elicited. In particular, the patient's imaging images were deceptive and not typical of a gastric bubble image and even if this patient is encountered again clinicians and radiologists may not recognize this as a gastric bubble image. Finally, surgeons are not sufficiently knowledgeable about Enterococcus faecium. Enterococcus faecium is gram-positive, facultative anaerobic cocci that is a commensal gastrointestinal organism and rarely associated with intrapleural infections. Prior reports of Enterococcus faecium empyema have primarily been associated with fistulization between the gastrointestinal system and the pleural space. Brown reported a case of a patient requiring ECMO support after COVID-19 who subsequently developed an E. fecalis intrathoracic abscess. I believe that encountering E. faecium again is something we remember in vivid detail [10].

Conclusion

This case provides clinicians with a new direction to think about when diagnosing pyothorax, particularly pyopneumothorax and to always beware of gastric vesicular images when a gas cavity is present. It is even more important to think deeply about the clinical diagnosis when gastrointestinal bacteria are present to avoid misdiagnosis again.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to disclose.

Authors' Contributions

Gaohua Liu participated in the care of the patient. Gaohua Liu, and Juan Wang performed the literature review and drafted the manuscript. Gaohua Liu, and Yi Yao obtained the image data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

There was no source of funding for our research.

Availability of Data and Materials

Not applicable

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Informed consent for publication was obtained.

References

- Kajal P, Bhutani N, Goyal M, Kamboj P (2017) Iatrogenic gastric perforation in a misdiagnosed case of late presenting congenital diaphragmatic hernia: Report of an avoidable complication. Int J Surg Case Rep 41: 154-157.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hassan M, Patel S, Sadaka AS, Bedawi EO, Corcoran JP, et al. (2021) Recent insights into the management of pleural infection. Int J Gen Med 14: 3415-3429.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li R, Sun M, Zhao M, Lu J (2023) Successful treatment of spontaneous diaphragmatic hernia with gastric necrosis: A case report. Asian J Surg 46: 2590-2591.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kajal P, Bhutani N, Goyal M, Kamboj P (2017) Iatrogenic gastric perforation in a misdiagnosed case of late presenting congenital diaphragmatic hernia: Report of an avoidable complication. Int J Surg Case Rep 41: 154-157.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nigo M, Vial MR, Munita JM, Jiang Y, Tarrand J, et al. (2016) Fungal empyema thoracis in cancer patients. J Infect 72: 615-621.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lin KH, Liu YM, Lin PC, Ho CM, Chou CH, et al. (2014) Report of a 63-case series of Candida empyema thoracis: 9-year experience of two medical centers in central Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 47: 36-41.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ko SC, Chen KY, Hsueh PR, Luh KT, Yang PC (2000) Fungal empyema thoracis. Chest 117: 1672-1678.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Swaminathan N, Anderson K, Nosanchuk JD, Akiyama MJ (2022) Candida glabrata empyema thoracis-A post-COVID-19 complication. J Fungi (Basel) 8: 923.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Meyer CN, Armbruster K, Kemp M, Thomsen TR, Dessau RB (2018) Pleural infection: A retrospective study of clinical outcome and the correlation to known etiology, co-morbidity and treatment factors. BMC Pulm Med 18: 1-8.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lian R, Zhang G, Zhang G (2017) Empyema caused by a colopleural fistula: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 96: e8165.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Citation: Liu G, Yao Y, Wang J (2025) A Complicated Case of Diaphragmatic Hernia Combined with Pyothorax. Diagnos Pathol Open 10: 255.

Copyright: © 2025 Liu G, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Open Access Journals

Article Usage

- Total views: 148

- [From(publication date): 0-0 - Dec 08, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 93

- PDF downloads: 55