A Morphologically Unusual Echinococcus granulosus (G1 Genotype) Cyst in a Cow from Kurdistan - Iraq

Published Date: 30-Sep-2015 DOI: 10.4172/2161-1165.S2-005

Abstract

Cystic (CE) and alveolar (AE) echinococcosis caused by the metacestode larval stage of Echinococcus granulosus sensu lato and Echinococcus multilocularis respectively are globally distributed zoonotic infections of public health importance. Molecular techniques have proven to be invaluable tools in the study of Echinococcus species. However, prior to the advent of DNA approaches and their routine application, morphological identification of E. multilocularis was reported from aberrant intermediate hosts such as cattle from various geographical locations. During a routine veterinary inspection at the Sulaimani Province abattoir (Kurdistan region, Iraq), an unusual echinococcal cyst embedded within a dense stroma resembling an E. multilocularis infection was observed in a cow liver. DNA amplification and analysis of a fragment within the cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (cox 1) mitochondrial gene revealed that the infection was caused by Echinococcus granulosus (G1 genotype). This finding highlights the importance of DNA molecular confirmatory tests to differentiate between cystic and alveolar echinococcosis particularly in areas where the latter disease is rare.

Keywords: Alveolar and cystic hydatidosis; Echinococcus granulosus G1 genotype; Echinococcus multilocularis; Kurdistan-Iraq

167281Introduction

Cystic (CE) and alveolar (AE) echinococcosis caused by the metacestode larval stage of Echinococcusgranulosus sensu lato (s.l.) and Echinococcusmultilocularis respectively are globally distributed zoonotic infections of public health importance [1]. E. granulosus (s.l.) is mainly transmitted within a domestic cycle involving dogs and ungulates as definitive and intermediate hosts, respectively. E. multilocularis is perpetuated within a wildlife cycle utilizing foxes as definitive hosts and small rodents such as voles as intermediate hosts. Molecular techniques have proven to be invaluable tools in the study of Echinococcus species, not least in elucidating phylogenetic relationships. For example the analysis of mitochondrial and nuclear genes have shown E. granulosus (s.l.) to include E. granulosus sensu stricto (s.s.) (G1-G3 genotypes), E. equinus (G4), E. ortleppi (G5) and E. canadensis (G6-G10) [2,3]. In addition, E. felidis which has been shown to be phylogenetically closely related to E. granulosus (s.s.) has been identified as a distinct species [4]. DNA techniques have also included the use of molecular probes for the unambiguous identification of Echinococcus species from both tissue and canid faeces [5]. However, prior to the advent of DNA approaches and their routine application, morphological identification of E. multilocularis was reported from aberrant intermediate hosts from various geographical locations. For instance, a cyst structure resembling that of E. multilocularis was described from cattle liver from Slovenia [6] and Iran [7]. Further to this, 0.05% of cattle and 0.02% of sheep from Romania were reported to harbour E. multilocularis cysts [8]. In addition, E. multilocularis was identified in 0.0015% (3/209,670) of cattle from the Carpathian Mountains in Romania [9]. The cysts were described as consisting of numerous vesicular cauliflower-like formations (0.8-2.5 cm in diameter) with continuous proliferation. In this case report we describe and molecularly analyze the causative agent responsible for an unusual case of hydatidosis in a cow from Kurdistan-Iraq and relate our findings to other unusual CE presentations in livestock animals and humans.

Materials and Methods

During a routine veterinary inspection carried out in June 2014 at the Sulaimani Province abattoir (Kurdistan region, Iraq), an unusual cyst morphologically similar to an E. multilocularis lesion was observed in the liver of a 3 and a half year old cow. Microscopical inspection of the cyst fluid was carried out using published methodology [10]. The inner membrane of this cyst was fixed in 75% (v/v) ethanol and couriered to the European Union Reference Laboratory for Parasites (EURLP, Rome, Italy; http://www.iss.it/crlp/) for further investigations. Genomic DNA was extracted from ethanol-fixed germinal layer in duplicate using the Wizard Magnetic DNA Purification System for Food (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The amplification of a 351 base pair fragment within the cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (cox 1) mitochondrial gene was carried out using published protocols [11,12]. Amplified products were commercially sequenced in both directions (BMRg, Padua, Italy) and the generated sequences were examined using Accelrys Gene 2.5 program (Accelrys, Cambridge, UK) and compared against the NCBI database through the use of BLAST algorithm (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/). Amino-acid sequences were inferred from the nucleotide sequences using the mitochondrial echinoderm and flatworm genetic code [13] using the Accelrys Gene 2.5 program.

Results

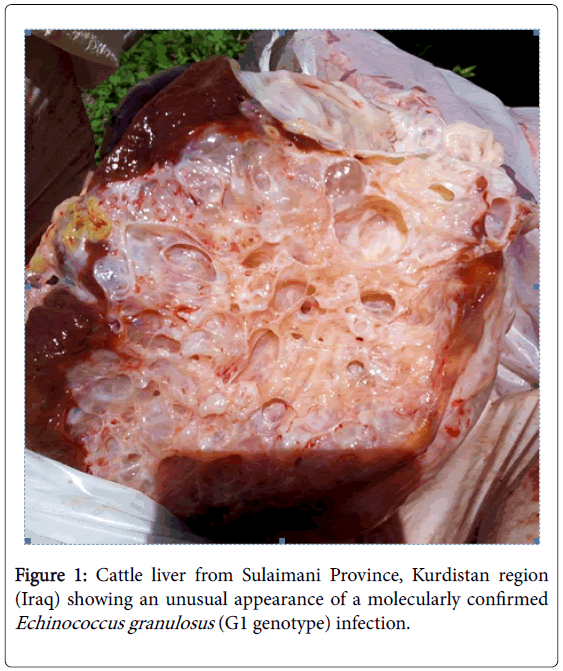

Morphological inspection of the cow liver revealed a hydatid cyst measuring 6 × 8 cm embedded within a dense stroma of thin membranes and somewhat large vesicles (Figure 1) and the examination of the cyst fluid revealed the presence of viable protoscoleces. Nucleotide sequence analysis using BLAST algorithm showed that the DNA extracted from the cow hydatid cyst had a 100% identity with the cox 1 mitochondrial gene of E. granulosus G1 genotype (Accession no. KT254117). The nucleotide sequence generated in this study was deposited in GenBank under accession number KR107135.

Discussion

In this study we reported an unusual presentation of cystic hydatidosis caused by E. granulosus G1 genotype in the liver of a cow from Kurdistan-Iraq. According to information obtained from veterinarians at the Sulaimani Province abattoir, the slaughtered cow had originated from neighboring Iran. Due to the endemicity of hydatidosis in livestock animals in both Iran and Iraq no conclusion could be drawn as to where the hydatid infection in this Kurdistan-Iraqi cow was sustained. Cystic hydatidosis in cattle from Iraq has been reported by several authors, for example prevalence rates of 10.9% and 29.8% cyst fertility have been recorded from Erbil, the regional capital of the Kurdistan autonomous region of Iraq [14].

We speculate that the cyst structure observed in this study may have formed as a result of physical damage that subsequently gave rise to daughter cysts in a similar manner to changes seen to occur in CE2 stage human cysts described in the Informal Working Group on Echinococcosis (WHO-IWGE) standardized classification [15]. A similar hydatid structure to that observed in this study was previously reported from Sichuan, China. Multilocular cysts found in yaks (Bos grunniens) were morphologically characterized as E. multilocularis but subsequent histologic and molecular analysis confirmed that the infection was caused by E. granulosus. The authors concluded that the manifestation of an immune response to E. granulosus was responsible for the laminated and germinal membranes continuing to proliferate without limitations [16]. More recently, multivesicular cysts in 2 cows from Turkey morphologically similar to alveolar echinococcosis lesions were molecularly confirmed to have been caused by E. granulosus G1 genotype [17].

Reports on the occurrence of E. multilocularis cysts in atypical hosts such as bovines that have not been confirmed using molecular DNA investigations are to be viewed with caution particularly in the absence of documented AE cases within the human population and animal intermediate hosts. Necropsy of stray dogs from several Iraqi Provinces have morphologically identified E. granulosus as the sole causative agent of canine echinococcosis in Iraq [14,18-20] and epidemiological studies have described cystic hydatidosis from sheep, goats and cattle from various regions [14,21]. To the best of our knowledge no molecular analysis of Echinococcus adult tapeworms from Iraqi definitive hosts has to date been conducted.

In terms of human infection, the majority of published reports based almost entirely on hospital records have documented the presence of only CE from several regions of Iraq [22-25]. Further, molecular confirmation of E. granulosus G1 genotype has been reported from 12 [26] and 30 [27] surgically confirmed cases from Kurdistan-Iraq as well as from several Iraqi regions, respectively. In contrast, only two human AE cases have been described from Iraq, one from the Zakho district of northern Kurdistan [28] and the other from Basra in the south of the country [29]. Although the presence of E. multilocularis in the mountainous areas of northern Iraq that border with a known AE echinococcosis endemic Turkish region cannot be excluded, yet the diagnosis of AE in a 40 year old female farmer from Zakho district, who had never left the region, was largely based on histologic data. It would be of interest to retrospectively examine pathology blocks of this particular case if this were now possible. However, the second E. multilocularis case is a recent report of the disease from Basra [29], yet surprisingly the authors did not confirm their diagnosis using DNA-based molecular methods. Careful examination of the published computer tomography (CT) image was carried out by experts within the field (Francesca Tamarozzi and Enrico Brunetti, pers. communication) who concluded that the depicted structure appeared to be similar to a CE3b stage (according to WHO-IWGE classification) of cystic echinococcosis.

An accurate diagnosis of Echinococcus at species level in animal hosts is important from an epidemiological point of view. However, misdiagnosis in humans could have an adverse impact on the clinical management of patients. In view of the fact that no DNA-based molecular confirmation was provided, we query whether some of the human AE cases documented outside the distribution range of this disease such as in North Africa [30-32] could be attributed to similar unusual patterns of CE infections.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge funding from the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme under the grant agreement 602051 (Project HERACLES; http://www.heracles-fp7.eu/).

References

- McManus DP, Zhang W, Li J, Bartley PB (2003) Echinococcosis.Lancet 362: 1295-1304.

- Nakao M, McManus DP, Schantz PM, Craig PS, Ito A (2007) A molecular phylogeny of the genus Echinococcus inferred from complete mitochondrial genomes. Parasitology 134: 713-722.

- Thompson RC (2008) The taxonomy, phylogeny and transmission of Echinococcus. ExpParasitol 119: 439-446.

- Hüttner M, Nakao M, Wassermann T, Siefert L, Boomker JD, et al. (2008) Genetic characterization and phylogenetic position of Echinococcusfelidis (Cestoda: Taeniidae) from the African lion. Int J Parasitol 38: 861-868.

- McManus DP (2006) Molecular discrimination of taeniidcestodes. ParasitolInt 55 Suppl: S31-37.

- Senk J, Brglez J (1966) NalazhidatidozeEchinococcusmultilocularisveterinorumkodgoveda (Finding of hydatidosisEchinococcusmultilocularis in cattle). Vet. Glasnik. 6: 429-432.

- Afshar A, Amri A, Sabai M, Naghshineh R (1969) Cysts resembling Echinococcusmultilocularis cysts in a cow in Iran. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 63: 499.

- Olteanu G, Panaitescu D (1984) Echinococcosis-hydatidosis, alveococcosis, coenurosis, cysticercosis and taeniosis in man and animals in Romania. Central Vet. Labor, Bucuresti, pp. 1-26.

- BarabA SS, Bokor E, Feke A, Nemes I, Murai A, et al. (1995) Occurrence and epidemiology of Echinococcusgranulosus and E. multilocularis in the Covasna County, East Carpathian Mountains, Romania. ParasitolHung28: 43-56.

- Smyth JD, Barrett NJ (1980) Procedures for testing the viability of human hydatid cysts following surgical removal, especially after chemotherapy. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 74: 649-652.

- Bowles J, Blair D, McManus DP (1992) Genetic variants within the genus Echinococcus identified by mitochondrial DNA sequencing. MolBiochemParasitol 54: 165-173.

- Casulli A, Interisano M, Sreter T, Chitimia L, Kirkova Z, et al. (2012) Genetic variability of Echinococcusgranulosussensustricto in Europe inferred by mitochondrial DNA sequences. Infect Genet Evol 12: 377-383.

- Nakao M, Sako Y, Yokoyama N, Fukunaga M, Ito A (2000) Mitochondrial genetic code in cestodes. MolBiochemParasitol 111: 415-424.

- Saeed I, Kapel C, Saida LA, Willingham L, Nansen P (2000) Epidemiology of Echinococcusgranulosus in Arbil province, northern Iraq, 1990-1998. J Helminthol 74: 83-88.

- Brunetti E, Kern P, Vuitton DA; Writing Panel for the WHO-IWGE (2010) Expert consensus for the diagnosis and treatment of cystic and alveolar echinococcosis in humans. Acta Trop 114: 1-16.

- Heath DD, Zhang LH, McManus DP (2005) Short report: Inadequacy of yaks as hosts for the sheep dog strain of Echinococcusgranulosus or for E. Multilocularis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 72: 289-290.

- Kul O, Yildiz K (2010) Multivesicular cysts in cattle: characterisation of unusual hydatid cyst morphology caused by Echinococcusgranulosus. Vet Parasitol 170: 162-166.

- Molan AL, Saida LA (1989) Echinococcosis in Iraq: prevalence of Echinococcusgranulosus in stray dogs in Arbil Province. Jpn J Med SciBiol 42: 137-141.

- Molan AL (1993) Epidemiology of hydatidosis and echinococcosis in Theqar Province, southern Iraq. Jpn J Med SciBiol 46: 29-35.

- Abdullah IA, Jarjees MT (2005) Worm burden, dispersion and egg count of Echinococcusgranulosus in stray dogs of Mosul City, Iraq. Raf Jour Sci 16: 8-13.

- Al-Abbassy SN, Altaif KI, Jawad AK, Al-Saqur IM (1980) The prevalence of hydatid cysts in slaughtered animals in Iraq. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 74: 185-187.

- Al-Barwari SE, Saeed IS, Khalid W, Al-Harmni KI (1991) Human Hydatidosis in Arbil, N. Iraq. J Islamic AcadSci 4: 330-335.

- Al-Amran FGY (2008) Surgical experience of 825 patients with thoracic hydatidosis in Iraq. IJTCVS 24: 124-128

- Shehatha J, Alward M, Saxena P, Konstantinov IE (2009) Surgical management of cardiac hydatidosis. Tex Heart Inst J 36: 72-73.

- Elhassani NB, Taha AY (2015) Management of Pulmonary Hydatid Disease: Review of 66 Cases from Iraq. Case Reports in Clinical Medicine 4: 77-84

- Hama AA, Mero WMS, Jubrael JMS (2012) Molecular characterization of E. granulosus, first report of sheep strain in Kurdistan-Iraq. 2nd International Conference on Ecological, Environmental and Biological Sciences (EEBSâ„¢ 2012). Oct. 13-14, Bali, Indonesia.

- Baraak MJM (2014) Molecular study on cystic echinococcosis in some Iraqi patients. PhD thesis, University of Baghdad, Iraq.

- Al-Attar HK, Al-Irhayim B, Al-Habbal MJ (1983) Alveolar hydatid disease of the liver: first case report from man in Iraq. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 77: 595-597.

- Benyan AK, Mahdi NK, Abdul-Amir F, Ubaid O (2013) Second reported case of multilocularhydatid disease in Iraq. Qatar Med J 2013: 28-29.

- Robbana M, Ben Rachid MS, Zitouna MM, Heldt N, Hafsia M (1981) [The first case echinococcusmultilocularis in Tunisia (author's transl)]. Arch AnatCytolPathol 29: 311-312.

- Zitouna MM, Boubaker S, Dellagi K, Ben Safta Z, Hadj Salah H, et al. (1985) [Alveolar echinococcosis in Tunisia. Apropos of 2 cases]. Bull SocPatholExotFiliales 78: 723-728.

- Maliki M, Mansouri F, Bouhamidi B, Nabih N, Bernoussi Z, et al. (2004) [Hepatic alveolar hydatidosis in Morocco]. Med Trop (Mars) 64: 379-380.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 16487

- [From(publication date): 0-2015 - Aug 30, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 11736

- PDF downloads: 4751