Canine Transmissible Venereal Tumor: A Review

Received: 20-Mar-2024 / Manuscript No. JVMH-24-130130 / Editor assigned: 25-Mar-2024 / PreQC No. JVMH-24-130130 (PQ) / Reviewed: 10-Apr-2024 / QC No. JVMH-24-130130 / Revised: 07-Mar-2025 / Manuscript No. JVMH-24-130130 (R) / Published Date: 14-Mar-2025

Abstract

Canine Transmissible Venereal Tumor (CTVT) is a neoplasm transmitted by the physical transfer of viable tumor cells by direct contact with injured skin and/or mucous tissue, as well as in stray and feral dogs that engage in unrestricted sexual behavior. CTVT also known as infectious sarcoma, venereal granuloma, transmissible lymphosarcoma or Sticker´s sarcoma, is a benign reticuloendothelial tumor of the dog that mainly affects the external genitalia and occasionally the internal genitalia. As it is usually transmitted during coitus, it mainly occurs in young, sexually mature animals. The altered tumor cell is the primary cause of CTVT, an uncommon, naturally transmissible and contagious tumor that spreads throughout the host like a parasite allograft. In immunocompetent adults, CTVT progresses in a unique way because it follows a regular growth pattern that comprises progressive, stable and regression phases while metastasis occurs in puppies and immunosuppressed dogs. The animal shows a tumorous mass in the penis and foreskin and a hard, painless subcutaneous mass, without disruption of structural integrity in the head. Gross findings of small nodule-like lesions which are hyperemic and they range in size from a small nodule (5 mm) to a large mass (>10 cm) that is firm, though friable on the external genitalia of both sexes of dog is the most consistent clinical finding. The surface is often ulcerated and inflamed and bleeds easily. The tumor does not often metastasize except in puppies and immune compromised dogs. Smears made from the tumor reveal round cells with vacuoles and mitotic figures. Histologically, CTVT cells exhibit radially arranged around blood and lymphatic vessels and have a high nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio around a nucleus. Three weekly intravenous injections of vincristine sulfate given in conjunction with ivermectin can cure the majority of cases. Because of the role that stray and wild dogs play in spreading the disease, it is necessary to treat afflicted dogs promptly and provide longterm animal birth control in stray dogs.

Keywords

Canine transmissible venereal tumor; Contagious; Dogs; Morphology; Sticker's sarcoma; Vincristine

Abbreviations

CTVT: Canine Transmissible Venereal Tumor; MHC: Major Histocompatibility Complex; TILs: Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes

Introduction

Cancer arises when a single cell lineage obtains somatic mutations that promote it toward a program of continued proliferation. Natural selection favors the most prolific subclones, often steering cancer toward a more aggressive phenotype. By its nature, cancer is counters elective and often lethal to its host and thus cancer is usually an ultimately short-lived and self-destructive entity [1].

Canine transmissible venereal tumor, which is the most common of genital tract tumors of canine species, is also known as canine Sticker’s sarcoma, venereal granuloma, contagiosum venereal sarcoma, contagiosum lymphosarcoma, canine condyloma, contagiosum lymphoma and infectious sarcoma. It has a relatively high incidence rate among all tumor types. It is a sexually transmissible, contagious, reticuloendothelial tumor of the dog that mainly affects the external genitalia and occasionally the internal genitalia. The tumor occurs naturally on the genitals of both male and female dogs. In male dogs, it is located on the penis or praeputium and in females is present on the vagina or labia [2]. CTVT is a tumor that may also occur in extra-genital areas, especially in the conjunctiva mucosae, such as the oral cavity and nasal.

Metastasis of CTVT is uncommon, only occurring in puppies and immunocompromised dogs. Most of the reported metastasis cases are mechanical extensions of growth or transplantation. Metastasis occurs in less than 5% of cases, being observed in lymph nodes, spleen, skin and subcutaneous regions. Its surface is often with erosions, ulcers and inflamated. Also, this tumor could be solitary or multiple, but always is located on the external genitalia [3]. It is transmitted from animal to animal during copulation. The tumor does not often metastasize except in puppies and immunocompromised dogs. Some invasive agents (such as leischmaniasis) which reduce the immune response of the host could cause the persistence of the lesions.

Literature Review

CTVT is a contagious cancer that is transmitted along with viable cells and fails to cross the barriers of the major histocompatibility complex between dogs and between family members in the Canidae family such as foxes, coyotes and jackals. CTVT was first described by Novinsky in 1876, which showed that the tumor could be transplanted from one susceptible host to another by inoculation of tumor cells. The transmissible agent causing Canine Transmissible Venereal Tumor (CTVT) is thought to be the tumor cell itself. Numerous cases of CTVT in the free dog populations of Romania have favored the spread of tumors and transmission of chemotherapy resistance from one dog to another [4]. It usually responds very well to polychemotherapy, although there are areas with small populations that show satisfactory results to monochemotherapy.

This tumor is unique in oncology because it was the first tumor to be transmitted experimentally, this being achieved by the Russian veterinarian Nowinsky in 1876. This stimulated a lively interest among scientists and became a new starting point for the study of oncology. Due to the unique nature of transmission by sexual contact, naturally occurring CTVT generally develops in the external genitalia. Less commonly, the tumor may also be transmitted to the nasal or oral cavities, skin and conjunctive and the rectum by sniffing or licking.

Although TVT has a cosmopolitan distribution, it is most frequently encountered in tropical and subtropical zones. Dogs of any breed, age or sex are susceptible. Young dogs, stray dogs and sexually active dogs are most frequently affected by this neoplasm. It has a worldwide distribution and the incidence in highest in tropical and subtropical regions. This tumor affects dogs (Canis familiaris) and can also infect other canids, such as foxes, coyotes and wolves. Although dogs over one year of age are at high risk in endemic areas, most common in dogs 2 to 5 years old [5].

Diagnosis of CTVT depends on anamnesis, clinical symptoms, cytology and histopathological results. It has a cauliflower-like shape and it could be pendular, nodous, papilar or multilobular and we can observe the drainage of a serosanguinous secretion, foul smell, licking of the affected region, dysuria, ulceration and necrosis. In diagnostic cytology, CTVTs are observed as big, round, discrete cells with a large nucleus and distinct intra-cytoplasmic vacuoles. There are vacuoles and a big nucleus in those cells. A dark-colored nucleolus appears in the nucleus.

The goal of CTVT treatment is a complete elimination of tumor cells by surgery, radiotherapy, immunotherapy and/or chemotherapy. Surgical methods are not successful enough in 50%-68% of CTVT cases due to an invasive and big tumoral tissue structure. However, chemotherapy is a considerably efficient method of treatment. Chemotherapy with vincristine sulfate is the first choice of treatment for CTVT and it has shown to be efficient. Its dose can vary from 0.50 mg/m² to 0.75 mg/m², applied weekly for four to six weeks [6].

Discussion

Cytogenic feature and origin of canine transmissible venereal tumor

The transmissible venereal tumor is a contagious and sexually transmissible neoplasia of unknown origin and in natural conditions, only affects dogs and experimentally, other species. Even though the exact cytogenic origin of CTVT is unknown, reports have supported the hypothesis of histocytic (reticuloendothelial) origin [7]. Its histological origin has yet to be established, none the less, histochemical studies have pointed to a histiocytic type of cell origin. It was first studied in 1876 by Novinsky and later by Smith and Washbourn. CTVT was first described as a transmissible and transplantable tumor and has been transplantable since the first description, over 100 years ago.

CTVT cells can be derived following mutations induced by viruses, chemicals or radiation of lymphohistiocytic cells and these clones of tumor cells can then be disseminated by allogeneic transplantation. The microsatellites were used to determine the timing of the origin of CTVT indicating that CTVT probably arose from a single wolf approximately 7,800 to 78,000 years ago. More recently, a single clone became dominant and then divided into two groups with worldwide distribution. This indicates that CTVT is the oldest transplantable somatic cell clone known. The normal diploid number of chromosomes in the somatic cell of the dog (Canis familiaris) is 78 and 76 of these, the autosomal chromosomes are acrocentric, while two, the sex chromosomes are metacentric [8].

There is a remarkable aberration in the numbers and morphology of the chromosomes of the constituent cells of CTVT. All dog chromosomes except X and Y are acrocentric; having acentromere very near to the end of the chromosome, while many of the CTVT chromosomes are metacetric or submetacentric, having a centromere nearer to the middle. Transmissible venereal tumor cells contain an abnormal number of chromosomes ranging from 57 to 64 and averaging 59, in contrast to the normal 78 of the species. Surface antigen characteristics suggest that all TVTs arose from a single original canine tumor [9]. The karyotypes of CTVTs from different geographical regions are similar suggesting that CTVT is transferred from one animal to another by transplantation of viable cells.

Etiopathogenesis

CTVT is usually transmitted to genital organs during sexual intercourse but can affect the skin via the direct implantation of tumor cells during contact between skin and tumor masses. CTVT transmission may be enhanced both by the extended period of canine sexual intercourse, which involves the mates being ‘tied’ due to the expansion of the penis within the female genital tract and by the injuries to the genital mucosa that are frequently incurred as mates attempt to separate. However, a unique case of CTVT in a sexually immature, 11-month-old, virgin bitch showing entirely cutaneous lesions without any mucosal involvement, is also suggestive of transmission from the dam to the pup during social interactions such as grooming and other maternal behavior. Transplantation occurs when intact host tumor cells lose the expression of Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) class I and II molecules, enabling transposition of the tissue to a healthy animal by contact between skin and damaged mucosa.

Experimentally transferred CTVT tumors have three distinct phases of growth, described as progressive, stable and regressive. Tumors generally become palpable 10 to 20 days following experimental transfer. The initial progressive phase, which generally lasts for a few weeks, is characterized by a rapid increase in tumor volume with a doubling time of between 4 and 7 days and an estimated loss of 50% of cells. During the subsequent stable phase, there is markedly slower tumor growth with a doubling time of approximately 20 days and an estimated cell loss of 80 to 90%. Following the stable phase, which can last from weeks to months to indefinitely, up to 80% of CTVT tumors enter a regressive phase during which the tumor shrinks and eventually disappears. The regressive phase generally lasts between 2 and 12 weeks, during which time tumors as large as 100 centimeters cubic can disappear completely. Alternatively, rather than entering the regressive phase, between 1 and 20% of transplanted tumors enter a second phase of rapid growth which progresses to metastasis. Spontaneous regression of the tumor can occur, probably due to a response from the immune system.

Gross and microscopic characteristics

Small pink to red, 1 mm to 3 mm diameter nodules can be observed 2 or 3 weeks after transplantation of tumor cells. Initial lesions are superficial dermoepidermal or pedunculated. Then, multiple nodules fuse forming larger, red, hemorrhagic, cauliflower-like, friable masses. The masses can be 5 cm to 7 cm in diameter and then progress deeper into the mucosa as multi-lobular subcutaneous lesions with diameters that can exceed 10 cm-15 cm. Tumors bleed easily and while becoming larger, normally ulcerate and become contaminated. Cytological examination reveals the typical round to slightly polyhedral cells, with rather eosinophilic vacuolated thin cytoplasm and a round hyperchromatic nucleus with a nucleolus and a moderate number of mitotic figures. Histologically, CTVTs are made up of a homogenous tissue with a compact mass of cells that are mesenchymal in origin and the borders of which cannot easily be differentiated. There is frequently an infiltration of lymphocytes, plasma cells and macrophages.

Epidemiology of canine transmissible venereal tumor

Incidence: In many countries of the world, CTVT is observed in both sexes except in Antarctica. Female dogs are contaminated with CTVT more than males because only one infected male often mates with numerous females. It is rare in home-kept dogs. Although the low frequency of the tumor depends on the development level of the countries, it is commonly observed in young and sexually active stray dogs in urban areas where mating is not under control. CTVT is distributed in all continents of the world except Antarctica. CTVT is more common in tropical and subtropical regions, particularly in the southern United States, Central and South America, south-east Europe, Ireland, China, the Far East, the Middle-East and parts of Africa. There is a homogeneous distribution of the neoplasm across varying geo-climatic zones in India.

Risk factor for canine transmissible venereal tumor: Although dogs over one year are at high risk in endemic areas, CTVT is most common in dogs 2 to 5 years old. The mean ages (and ranges) of affected dogs are 3.9 (1-13) years. This type of tumor is more frequently found in females and is transmitted by coitus or by experimental transplant. It has been observed that the majority of afflicted animals are sexually active adults. Females (64.5%) are infected more often than males (35.5%) because one infected male often mates with numerous females, in free range or stray groups and also in kennels. Based on social behavior, the high-risk groups include habitually yard-escaping dogs (75.5%), guard dogs (41.3%) and hunting dogs (41.5); CTVT is rare in well-supervised home-kept companion animals (4%), occurring only after an escape eventuating into an unwanted copulation event.

Breeding and general management of kennels are considered to be playing a very important role here in the spread of this disease. Factors such as the purpose of dog keeping, red vulvar discharge as the sole breeding indicator, knowing the difference between normal red discharge and clotted blood and type of breeding partner were showing significant differences. The purpose of dog keeping is included in the final multivariable model that resulted in a higher risk of contracting disease. Guard dogs are also considered prone to the risk of getting CTVT. In canine breeding, red vulvar discharge in female dogs is considered a good indication of approaching oestrus but it should be further confirmed with vaginal cytology. Owners considering red vulvar discharge as the sole breeding indicator were posing their dogs to contract and spread this disease to other dogs.

Pathological characteristics

Clinico-pathological characteristics: The tumor may be solitary or multiple and is almost always located on the external genitalia, although it may occur in adjacent skin and oral, nasal and conjunctival mucosae. Incidence varies from relatively high in some parts of the body to rare in others. The tumor may arise deep in the prepuce or vagina and be difficult to see. This may lead to misdiagnosis if bleeding is confounded with estrus, urethritis, cystitis or prostatitis.

In female dogs, the neoplastic lesions are frequently located at vestibule (95.6%) and less often at the vagina (44.5%) or invading the vulvar lips (18.6%). Main lesions are almost always present at the ejection of the vestibule and vagina, perhaps because of the high pressure exerted on this area during the mating performance. In male dogs, neoplastic lesions are located on the more caudal part and less often on the shaft (parslongaglandis, 25.9%) or the tip (9.9%) of the glans penis. Initially, the tumor grows rapidly presenting a brightly sanguine coloration, commonly associated with the oozing of a hemorrhagic fluid (94.6%), to be followed by protrusion of the neoplastic lesions (31.3%) and deformation of the external genitalia (30.4%). The peculiar odor of the neoplastic lesions discharge (27.2%), which after secondary bacterial infection becomes particularly unpleasant and the excessive licking (5.8%) of the genitalia are also commonly noticed. Less commonly observed symptoms include dysuria (5.4%), weakness (4.6%), ulcers in the perineum area (2.1%), anorexia (1.7%), constipation (0.8%), paraphimosis (0.8%), mating refusal (0.4%) and weight loss (0.4%).

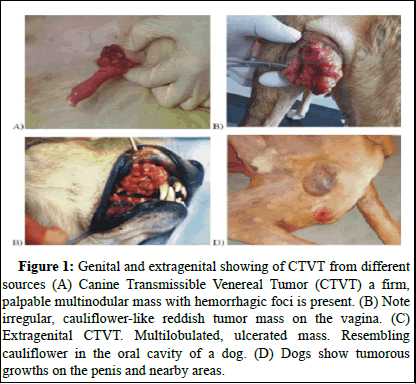

Primary genital tumor: In the bitch, the neoplasm is usually found in the posterior part of the vagina, often at the junction of the vestibule and the vagina. It sometimes surrounds the urethral orifice and if it is just within the vagina, it may protrude from the vulva. Tumors on the external genitalia of both sexes appear initially as small hyperaemic papules that later progress to nodular, papillary multilobulated, cauli£ower-like or pedunculated proliferations measuring up to 15 cm in diameter. The mass is firm but friable and the superficial part is commonly ulcerated and inflamed. CTVT is observed both at genital and extragenital areas (Figure 1).

Metastatic lesion: CTVT had extragenital lesions either by metastasis from a primary genital lesion or through implantation following a social behavior. But metastasis of CTVT from primary genital sites is uncommon. Metastasis occasionally occurs in the inguinal lymph nodes and the external iliac lymph nodes. Orbital growth of the tumor may cause blindness. Metastasis develops in less than 5%. Other sites of metastasis include skin, subcutaneous, distant lymph nodes, brain, eyes, spleen, liver, testicles, musculature, lungs, kidneys, anus, bones and mammary glands. Metastasis is rarely seen in internal genital organs like the uterus and ovaries. Swelling of the penis from preputial sheath having a large, friable, bloody, cauliflower-like mass in the region of bulbus glandis (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Genital and extragenital showing of CTVT from different sources (A) Canine Transmissible Venereal Tumor (CTVT) a firm, palpable multinodular mass with hemorrhagic foci is present. (B) Note irregular, cauliflower-like reddish tumor mass on the vagina. (C) Extragenital CTVT. Multilobulated, ulcerated mass. Resembling cauliflower in the oral cavity of a dog. (D) Dogs show tumorous growths on the penis and nearby areas.

Figure 2: Extrusion of the penis from preputial sheath revealing a large, friable, bloody, cauliflower-like mass in the region of bulbus glandis.

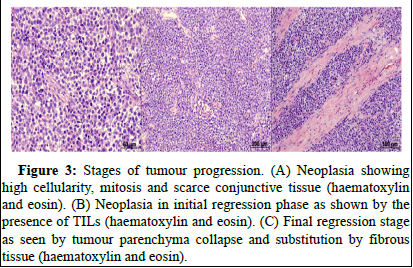

Histopathological characteristics: Histology of CTVT shows round cells, arranged or grouped in cords, interspersed with delicate conjunctival stroma when stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The tumor cells are usually arranged radially around blood and lymphatic vessels and have a high nucleus: Cytoplasm ratio with a round nucleus and chromatin ranging from delicate to coarse and prominent nucleoli.

Tumor cells contain a large quantity of cytoplasm that is slightly acidophilic with poorly defined limits. The tumor can be classified into progression and initial and final regression phases according to developmental stages (Figure 3). The progression phase presents as round cells arranged diffusely, interspersed by delicate conjunctival stroma and the frequent presence of mitotic structures. In the initial phase of regression, Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes (TILs) appear and are widely distributed or associated with the conjunctival stroma.

Figure 3: Stages of tumour progression. (A) Neoplasia showing high cellularity, mitosis and scarce conjunctive tissue (haematoxylin and eosin). (B) Neoplasia in initial regression phase as shown by the presence of TILs (haematoxylin and eosin). (C) Final regression stage as seen by tumour parenchyma collapse and substitution by fibrous tissue (haematoxylin and eosin).

Cytopathological characteristics: Both genital and extra-genital neoplasias present characteristic round cells with distinct cytoplasmic borders with Romanovisky staining. The nuclei are oval or round and centrally-located, with delicate chromatin and large nucleoli; the cytoplasm is slightly acidophilic and contains finely granular, delicate vacuoles and cells do not display anisokaryosis, anisocytosis, hyperchromasia or nuclear macrokaryosis. Mitoses are frequent, may be typical or atypical and are indicative of proliferation of tumor cells. Inflammatory cells such as lymphocytes, plasma cells, macrophages and neutrophils are observed regardless of the stage of neoplastic development.

Cytopathological characteristics: Both genital and extra-genital neoplasias present characteristic round cells with distinct cytoplasmic borders with Romanovisky staining. The nuclei are oval or round and centrally-located, with delicate chromatin and large nucleoli; the cytoplasm is slightly acidophilic and contains finely granular, delicate vacuoles and cells do not display anisokaryosis, anisocytosis, hyperchromasia or nuclear macrokaryosis. Mitoses are frequent, may be typical or atypical and are indicative of proliferation of tumor cells. Inflammatory cells such as lymphocytes, plasma cells, macrophages and neutrophils are observed regardless of the stage of neoplastic development.

Diagnostic method

CTVT is diagnosed based on the environmental history, clinical and cytological findings. Biopsy for histological examination is the most reliable method for diagnosis. Many of the diagnostic difficulties previously faced by pathologists have, however, been eased by the introduction of novel techniques such as immunohistochemistry and or immunocytochemistry and molecular biology.

Clinical and cytological diagnosis of canine transmissible venereal tumor: Definitive diagnosis of CTVT is based on physical examination and cytological findings typical of TVT in exfoliated cells obtained by swabs, fine needle aspirations or imprints of tumors. Clinical signs vary according to the localization of tumors. Dogs with genital localization have hemorrhagic discharge. In males, lesions usually localize cranially on the glans penis, on preputial mucosa or on the bulbus glandis. Tumoral masses often protrude from the prepuce and phimosis can be a complication. The discharge can be confused with urethritis, cystitis or prostatitis. A considerable hemorrhagic vulvar discharge may occur and can cause anemia if it persists. In cases with extra genital localization of the TVT, clinical diagnosis is usually more difficult because TVTs cause a variety of signs depending on the anatomical localization of the tumor, e.g., sneezing, epistaxis, epiphora, halitosis and tooth loss, exophthalmos, skin bumps, facial or oral deformation along with regional lymph node enlargement.

The cytological examination is a quick, efficient, inexpensive and relatively simple tool for the diagnosis of CTVT. Most of the morphologic aspects of diagnostic opinion come from individual cell morphology, which is clearer with the use of the imprint method. CTVT cells are large round cells with round nuclei, coarse chromatin, one to two prominent nucleoli, abundant and lightly basophilic cytoplasm and multiple punctate vacuoles.

The tumor cells displayed many hallmarks of malignancy, including pleomorphism, anisocytosis, anisocytosis, nuclear criteria of malignancy, coarsely aggregated chromatin, typically structured in a cord-like pattern and the majority of them contained numerous, clearly visible, big basophilic nucleoli. CTVT tumor is a mixed type, because it contains both lymphocytoid and plasmacytoid cells, with neither type exceeding 59% of total cells.

Cytological evaluation is essential for diagnosis the of tumors of the genital tract in dogs. Canine histiocytoma shows three cell types: The first are oval or polygonal histiocytic cells with slightly acidophilic and occasionally vacuolated cytoplasm; the second type are plump spindle-shaped fi fibroblast-like cells; and the third type are multinucleated giant cells containing 2 to 35 nuclei and abundant cytoplasm. The mastocytoma tumor cells are medium in size, oval and polygonal in shape, with a centrally located nucleus and the cytoplasm is pale stained with eosin. B-cell lymphomas consist of large round cells, with nuclear polymorphism and variable amount of eosinophilic cytoplasm. Neoplastic plasma cells resemble very much CTVT cells, i.e., they are round to oval cells with predominantly round nuclei, coarsely clumped chromatin and variable amounts of pale basophilic cytoplasm, but they manifest low to moderate mitotic activity.

Hemato-biochemical diagnosis of canine transmissible venereal tumor: Hemato-biochemical shows this neoplasm is markedly elevated with neutrophilia, lymphopenia and thrombocytopenia. Serum chemistry is indicative of hypoproteinemia, hypoalbuminemia, hypoglobulinemia with higher levels of blood urea nitrogen and creatinine. Increased activities of alanine aminotransferase and alkaline phosphatase were also observed probably due to metastasis to these organs affecting the organ function.

Free radicals are highly reactive molecules produced during normal metabolism in the body, or after exposure to environmental factors, which are kept in equilibrium by the body through endogenous antioxidant defense mechanisms (Comprising of Superoxide Dismutase (SOD), Catalase (CAT), glutathione peroxidase, glutathione reductase and glutathione etc. If this balance is disturbed, it may result in oxidative stress, leading to enhanced lipid peroxidation, DNA strand breaks and protein damage. The role of oxidative stress in carcinogenesis is delineated in dogs with lymphoma. The hemato-biochemical study revealed a marked increase in the level of lipid peroxidation, a decreased level of reduced glutathione and reduced activities of superoxide dismutase and catalase. These alterations in oxidant-antioxidant status might be due to direct injury by tumor cells or inflammation and/or necrosis which needs further validation in similar types of cases.

Immunohistochemical diagnosis of canine transmissible venereal tumor: Most canine round cell tumors are immune-characterized using several tumor markers making it easy for accurate diagnosis and classification. Although CTVT is subjected to immunohistochemical studies with several tumor markers, its origin and the immunophenotype remain uncertain. However, immunohistochemical studies with a panel of several antibodies have managed to rule out some of the early suggestions.

For the diagnosis of TVT by immunohistochemistry a panel of antibodies is required. The tumors stain with antibodies against vimentin, lysozyme, α-1-antitrypsin and glial fibrillary acidic protein and are negative for keratins, S100 and muscle markers. CTVT cells are negative for keratins, -smooth muscle actin, desmin, CD3 and immunoglobulins G and M and this means that an epithelial, smooth muscle and T and B lymphocyte origin can be ruled out. Antibodies against CD3, surface immunoglobulins G and M are useful for differentiating CTVT from lymphomas and plasma cell tumors. Lysozyme and Alpha Antitrypsin (AAT) have been considered good markers for benign and malignant histiocytes and these antigens are not expressed by other mesenchymal cells.

Molecular diagnosis of canine transmissible venereal tumor: Molecular biology can also be useful in the diagnosis of canine TVT. It is identifying and characterizing a 70 kDa, temperature and pH labile TVT-specific antigen. A TVT-associated antigen from the sera of affected dogs. The c-myc oncogene is re-arranged in this tumor by insertion of a 1.5 kbp transposable sequence, known as the Long-Interspersed Element (LINE), 5’ to the first exon. Analysis of TVT samples from around the world has revealed that in all tumors the insertion of the same LINE occurs in the vicinity of the c-myc gene and a PCR amplification of the DNA segment covering the mutation area is of diagnostic importance. Heat Shock Proteins (HSPs) 60 and 70 are potential markers for TVT and HSP 60 appears to be involved in CTVT regression. A point mutation of the tumor suppressor protein p53 (T963C) resulted in the change of amino acid (Phe-Ser) in TVT cases. This mutation did not participate in the clonal origin of the tumor but was acquired at a later stage. Further, TVT tissue from bitches lacks surface estrogen receptor-α expression.

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnoses for CTVT included lymphoma, canine cutaneous histiocytoma, anaplastic mast cell tumor, amelanotic melanoma and poorly differentiated. The negative reactivity to CD3 and CD79 used as markers for T and B lymphocytes contributed to the differentiation of TVT from lymphoma, which was further supported by positive staining against vimentin. Positive staining for vimentin also excluded undifferentiated carcinoma, which was corroborated by the negative staining for cytokeratin. Negative S-100 protein allowed differentiation of CTVT from amelanotic melanoma. The neoplastic cells did not have metachromatic granules when stained with toluidine blue, which excluded anaplastic mast cell tumor. The possibility of canine cutaneous histiocytoma was excluded based on the anatomical location of the tumors and the cytologic features.

Immune response to canine transmissible venereal tumor

The development of CTVT is mediated by the immune system, where the outbreak of disease represents the success of the neoplasia in overcoming the host immune system. Puppies born to females exposed to CTVT are less likely to contract this cancer. In immunocompromised animals experimentally infected with viable CTVT cells, disease progression and metastasis are observed; however, those dogs who quickly recovered acquired immunity against subsequent implantations.

In healthy animals, CTVT regresses spontaneously. Regression is associated with the infiltration of lymphocytes and plasma cells and with necrosis and apoptosis. The transition between the progression and regression phases of CTVT is accompanied by a significant increase in the infiltration of TILs. The Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) class I and II molecules are either not expressed or are present on only a small subset of neoplastic cells during the progressive phase. Interestingly, a significantly greater proportion of CTVT cells express MHC class I and II in the regression phase.

Cytokines are also thought to play a role. Higher concentrations of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IFN-c are detected in ex vivo cultures of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes from regressing tumors compared with growing tumors and the presence of these cytokines increases the cytotoxicity of NK cells to CTVT cells in vitro. CTVT cells produce Transforming Growth Factor b1 (TGF) and showed that this cytokine inhibited NK cell activity, as well as tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte cytotoxicity. The suppressive effects of TGF b1 on NK cell-killing activity could be counteracted by the proinflammatory cytokine interleukin-6 (IL6), which is secreted by tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes.

Peripheral Blood Lymphocytes (PBL) of dogs in which Peripheral Blood Lymphocytes (PBL) of dogs in which CTVT had regressed, are cytotoxic to the tumor cells in contrast to PBL of normal dogs and animals during progressive tumor growth (Figure 4). The proportion of B lymphocytes in the peripheral blood decreased dramatically with CTVT growth. The destruction of B lymphocytes is caused by substances released by the tumor cells, such as cytotoxic proteins and other circulating substances. These cytotoxic substances cause B lymphocyte apoptosis during the neoplastic progression phase. Tumors are frequently infiltrated by T-lymphocyte and Natural Killer (NK) cells. Increased numbers of Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes (TILs), particularly T-lymphocytes, are associated with tumor regression in CTVT. The T-cell cytotoxicity is believed to be associated with apoptosis and apoptosis is increased in regressing CTVTs.

Figure 4: Model for canine transmissible venereal tumor immune evasion. CTVT has distinct phases of growth, progressive and regressive. During the progressive phase, the tumor cells do not express MHC class I or class II and the tumor secretes Transforming Growth Factor- 1 (TGF 1), a cytokine that inhibits tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (Including natural killer cell) cytotoxicity. Tumor cells may also inhibit some types of antigen-presenting cells. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes are present in low numbers. During the regressive phase, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes increase in number and their secretion of IFN and Interleukin-6 (IL6) counteract the repressive effects of tumor-derived TGF 1 and induces MHC class I and class II expression in tumor cells. MHC expression reveals CTVT as an allograft and it is rejected by both antibody-dependent and -independent cytotoxic processes.

Treatment

A high rate of spontaneous regression warrants proper caution in the evaluation of the success achieved with different therapeutic approaches. There are several options for treatment. Firstly, surgery, after surgery most tumors recur. Secondly radiotherapy: CTVT is sensitive to radiotherapy; however, radiotherapy is not available everywhere. Thirdly chemotherapy; is considered the treatment of choice for inoperable CTVT. A variety of single-agent and combination multi-agent protocols employing cyclophosphamide, vinblastine, methotrexate and prednisolone are frequently used, but none has demonstrated superiority to employing intravenous chemotherapy with vincristine alone. A fourth option is immunotherapy. Local therapy with IL2 is usually very effective; this is in contrast to systemic IL2 therapy.

Chemotherapy: A variety of single-agent and combination multi-agent protocols employing cyclophosphamide, vinblastine, methotrexate and prednisolone are frequently used, but intravenous chemotherapy with vincristine is mostly effective. Weekly intravenous administration of vincristine is presently the most effective and practical chemotherapy. The most frequent complication of vincristine therapy is the occurrence of local tissue lesions caused by extravasation of the drug during intravenous application, resulting in the development of necrotic lesions with crusts in non-tumorous tissue. The most effective, safe and convenient therapy in clinical practice is the use of vincristine as a single agent, but its extensive use in the CTVT treatments, combined with the existence of malignant neoplasm characteristics, has increased the number of applications of the drug. The use of vincristine in resistance is correlated with the overexpression of a protein molecule of the plasma membrane, called P-glycoprotein. The molecule is expressed in various tissues such as the kidney, liver, colon, brain, lung, peripheral blood and normal bone marrow. Tumors derived from tissues expressing high amounts of P-glycoprotein exhibit intrinsic resistance to chemotherapy, since this molecule acts as a carrier of the membrane, functioning as an efflux pump dependent on the energy generated by ATP hydrolysis, resulting in a range transport of drug into the extracellular medium, thus reducing its concentration to levels just lethal.

Some studies have shown that the combination of vincristine sulfate with ivermectin has shown beneficial, since this antiparasitic used as substrate the P-glycoprotein and thereby decrease the amount of the molecule in the tissue, thereby potentiating the antitumor treatment and slowing treatment resistance. Vincristine as a single agent application being performed weekly for six weeks, which is not suitable, since this drug is neurotoxic and cause gastrointestinal lesions, myelosuppression and lesions at the site of application. The antiparasitic uses the P-glycoprotein as a substrate for metabolism, these being excreted by kidney, biliary and intestinal route. Thus, the protocol used in the case of vincristine, association with ivermectin is effective in eliminating cancer of the penis and prepuce the animal since the amount of the chemotherapeutic applications is reduced to four weeks, a significant finding because promoted a decrease the number of administrations, faster recovery patient and reduced cost of treatment.

Although chemotherapy is effective in curing tumors in the genital region of the dog, on the other hand it is not effective in eliminating the CTVT subcutaneous head. The non-primary tumor masses have higher expression of P-glycoprotein. It is believed that for this reason, the subcutaneous tumor is more resistant to treatment with chemotherapeutic associated with ivermectin. In this case, we opted for surgical resection, followed by sessions with chemotherapy and immunomodulators.

Spermatogenesis can be temporarilly or permanently altered by the administration of cytotoxic drugs. Studies in laboratory animals have shown that vincristine damages the DNA of germ cells thereby reducing the rate of development of these cells. Vincristine can cause cytoplasmic protein precipitation, which in turn interferes with microtubule formation. Little information is available on the long-term effects of vincristine on male dog fertility and most of the studies only have described semen quality during treatment.

Surgical excision: Electrosurgical removal is widely used in veterinary clinics and provides improved hemostasis. However, it leads to greater postoperative pain due to the thermal injury. Cryosurgery can be used to reduce tumour recurrence, as it induces direct cellular death and vascular collapse, leading to tumour elimination. The recurrence rate after surgery and the difficulty in obtaining a complete excision in some locations, surgery becomes a bad option in many cases. In the case of CTVT metastatic, the surgery is useless, besides being an invasive and traumatic procedure with high risk of scar deformation (mainly electro dissection). The use of chemotherapy after surgical resection of the tumor is indicated in an attempt to prevent the recurrence of neoplastic tissue.

Immunotherapy: Immunotherapy is adopted in the case of immunosuppressed animals, using substances that act on the immune system. Local therapy with IL2 is usually very effective; this in contrast to systemic IL2 therapy. Local (intratumora) IL2 is therapeutically-effective against bovine ocular squamous cell carcinoma, canine mastocytoma, human nasopharyngeal carcinoma and recently it showed that CTVT is also sensitive to local IL2 therapy.

Radiotherapy: CTVT has already been proven to be highly sensitive to irradiation from the last century. Solacroup proposed radiation therapy for CTVT in Europe in 1950, which has been employed since, mainly in France resulting in a sufficient reduction of CTVT cases. Dosage recommendations range from 1500 to 2500 rads divided in sessions of 400–500 rads over a period of 1-2 weeks, or a single dose of 1000 rads which, if not curative, can safely be repeated one to four times. However, radiotherapy requires trained personnel, specialized equipment, high expenses, and, also, the foregoing necessity to chemically immobilize the dog. Therefore, its use is recommended only in cases where other treatments fail.

Prognosis

The prognosis for total remission is good unless metastatic involvement of the central nervous system or eye is present. CTVT is antigenic in the dog and the course of the disease is markedly influenced by the immune status of the dog. In healthy, immuno-competent, adult dogs, the tumor regresses spontaneously after a period of logarithmic growth, and the development of tumor immunity prevents successive occurrences. The chances of self-regression in tumors over 9 months of age were remote.

Conclusion

Since the beginning of civilization, dogs have been considered as the most trusted companion animal and nowadays dogs are the modern status symbol of society. Owners take pride and pleasure in flaunting them. Also, man adopts dog breeding as a source of income; CTVT is a great threat to this. CTVT is the most prevalent neoplasia of the external genitalia of the dog in tropical and sub-tropical areas. The tumor is transplanted from site to site and from dog to dog by direct contact with the mass and during coitus. Metastasis is uncommon (5%) and when it occurs, it is usually to the regional lymph nodes, but the kidney, spleen, eye, brain, pituitary, skin and subcutis, mesenteric lymph nodes and peritoneum may also be sites. Diagnosis is based on typical physical, cytological, histochemical and molecular findings. CTVT is curable in almost all cases with three cycles of vincristine sulphate intravenous injection at the dose rate of 0.025 mgkg−1 body weight. The general health status of animals should be ensured during the course of therapy.

Declaration

I declare that this review is an original report of my work, has been written by me, and has not been submitted for any previous degree. The work is almost entirely my labor; the collaborative contributions have been indicated clearly and acknowledged.

Consent for Publication

I, the undersigned, give my consent for the publication of identifiable details, which can include figures and/or details within the text to be published in the above Journal and Article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Dagne Tsegaye Leta (DVM, Ass. Prof. of Veterinary Pathology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Haramaya University, Ethiopia) for his constructive idea on the manuscript in advance.

Author Contribution

Elias Gezaw Anbu prepares, writes and edits the manuscript file.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

'Not applicable' for this review.

Funding

'Not applicable' for this review.

References

- Abuom TO, Mande JD (2006) Transmissible venereal tumor with subcutaneous and bone metastasis. Kenya Veterinary 30: 10-12.

- Alfred C (2013) Genital and extragenital canine transmissible venereal tumor in Dogs Greneda, West Indies. Vet J 3: 111-114.

- Amaral AS, Sandra BS, Isabelle F, Fonseca LS, Andrade FH, et al. (2007) Cytomorphological characterization of transmissible canine venereal tumor. RPCV 102: 253-260.

- Amariglio EN, Hakim I, Brok-Simoni F, Grossman Z, Katzir N, et al. (1991) Identity of rearranged LINE/c-MYC junction sequences specific for the canine transmissible venereal tumour. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 88: 8136–8139.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Andrade SF, Sanches OC, Gervazoni ER, Lapa FAS, Kaneko VM, et al. (2009) Comparison between two treatment protocols for transmissible venereal tumor in dogs. Veterinary Clinic 14: 56-62.

- Aprea AN, Allende MG, Idiard R (1994) Intrauterine transmissible venereal tumor: Case description. Vet Argentina XI 103: 192-194.

- Ayyappan S, Suresh Kumar R, Ganesh TN, Archibald David WP (1994) Metastatic transmissible venereal tumour in a dog. A case reports. Indian Vet J 71: 265-266.

- Bastan A, Duygu B, Mehmet C (20008) Uterine and ovarian metastasis of transmissible venereal tumor in a bitch. Turk J Vet Anim Sci 32: 65-66.

- Batamuzi EK, Kassuku AA, Agger JF (1992) Risk factors associated with canine transmissible venereal tumour in Tanzania. Prev Vet Med 13: 13- 17.

Citation: Anbu EG (2025) Canine Transmissible Venereal Tumor: A Review. J Vet Med Health 9: 284.

Copyright: © 2025 Anbu EG. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Usage

- Total views: 106

- [From(publication date): 0-0 - Oct 25, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 69

- PDF downloads: 37