Case Report Open Access

Chediak-Higashi Syndrome with Novel Gene Mutation

Mostafa Helmi Abdulaziz*Department of Endocrinology, Dubai Hospital, Alkhaleej, Dubai, UAE

- *Corresponding Author:

- Mostafa Helmi Abdulaziz

Department of Endocrinology, Dubai Hospital, Alkhaleej, Dubai, UAE

Tel: +00971507889196

E-mail: mailto:mhAbdulAziz@dha.gov.ae

Received date: June 8, 2016; Accepted date: July 28, 2016; Published date: August 5, 2016

Citation: Abdulaziz MH (2016) Chediak-Higashi Syndrome with Novel Gene Mutation. J Gastrointest Dig Syst 6:463. doi:10.4172/2161-069X.1000463

Copyright: © 2016 Abdulaziz MH, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Gastrointestinal & Digestive System

Abstract

Chediak-Higashi syndrome (CHS) is a rare disorder of immune deficiency with autosomal recessive inheritance. This syndrome is caused by mutations in the CHS1/LYST gene located on chromosome 1. It leads to abnormal intracellular protein transport and alters lysosomes granules function and morphology. Herein, we report a case of CHS. This two-and-half-years-old boy presented with pneumonia. Genetic evaluation revealed novel mutations in the CHS1 gene: c.6159_6160del (p.Met2053Ilefs*31) variant, which has not previously described in any literature. To date less than 75 mutations have been described for this syndrome. This case is reported for its novel mutation and absent accelerated phase to date. Awareness, early recognition, and management of the condition may prevent the preterm morbidity associated.

Keywords

Chediak-Higashi; Immune deficiency; Gene mutation; Lysosome

Introduction

Chediak-Higashi Syndrome (CHS) is a rare autosomal recessive immune disease characterized by oculocutaneous albinism, a predisposition for infections, coagulopathies, neurological dysfunction, and large granules in many cell types [1]. CHS caused by homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations of the CHS1 gene. This gene, which was originally called (LYST), a lysosomal trafficking regulatory gene, is mapped to chromosomal locus 1q42.1-q42.2 [2,3].

The syndrome is categorized into classic and atypical (mild) forms. Children with the classic form of the disease are at risk for developing the accelerated phase. The accelerated phase of CHS is termed hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) [4], presented in almost 85% of patients. This phase is a form of lymphoproliferative infiltration of bone marrow and reticuloendothelial system. Nevertheless, in the atypical form, the accelerated phase has a later onset, a history of unusual or severe infections is absent and neurological impairment is more prominent.

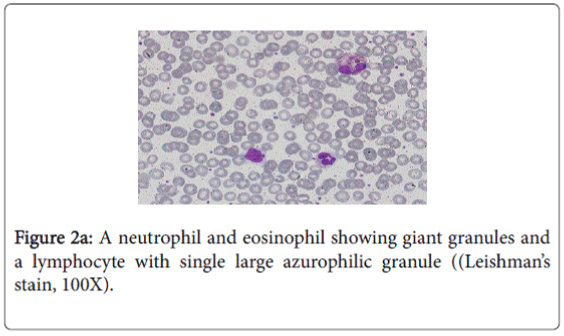

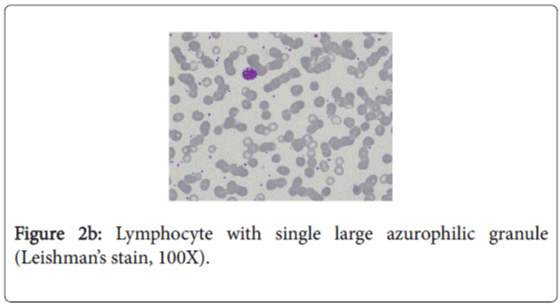

The diagnosis of CHS is usually made by the presence of ‘giant granules’ in microscopic analysis of white blood cells.

In this report, our patient was presented with atypical mild form of CHS, diagnosed by the presence of large granules in the cytoplasm of neutrophils, eosinophils, and in few lymphocytes in blood film. The genotype of our patient identified the causative mutation in LYST. We found a homozygous c.6159_6160del (p.Met2053Ilefs*31) variant which is most likely a disease-causing mutation. Yet it was not reported previously.

Case Presentation

A two year and six months old boy, admitted with right sided pneumonia, which did not improve on antibiotics. Prior to admission, the child had a history of fever and poor appetite of 2 weeks duration. He has no cough, sweating, vomiting, diarrhea, urinary symptoms. The child had history of recurrent wheezing which was managed by nebulized bronchodilators. Moreover, there was a history of skin discoloration and weight loss for the last 8 months. The child gave history of infantile eczema. One year back, he attended the ED with his parent, with scalp abscess which was resolved by oral antibiotics. The child was born term by LSCS (Lower segment Caesarean section) due to previous LSCS and Placenta previa. His mother had Gestational Diabetes. He had an uneventful prenatal, natal and postnatal history. His birth weight was 3 Kg. He was born to consanguineous parents; his parents are cousins. He has two healthy elder brothers and a sister. His vaccination schedule was up to date. There was a history of contact with caregiver, who had old treated tuberculosis.

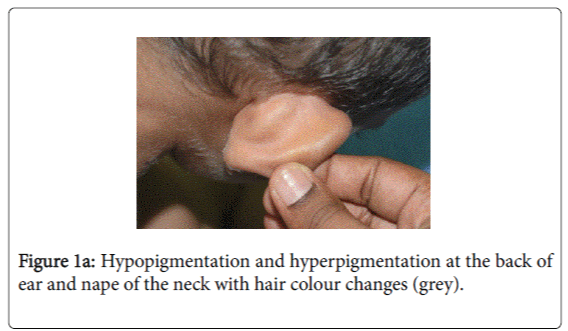

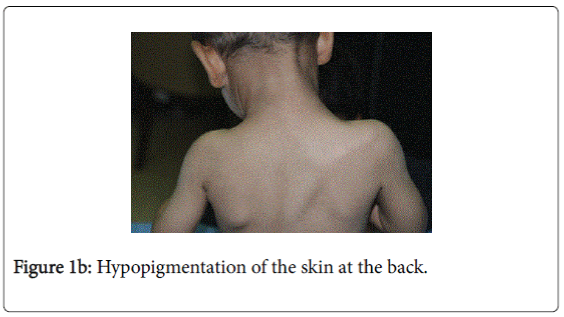

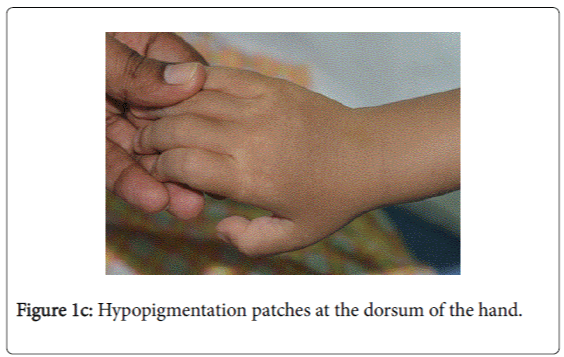

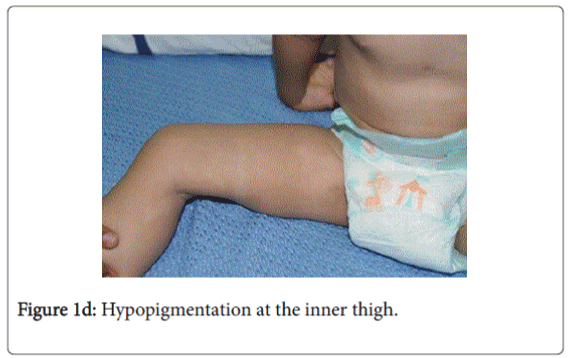

On examination, he was afebrile with normal vital signs. His general condition was good apart from pallor with good nutritional status. No lymph nodes were palpable. He has greyish short sparse hair. There was hyper-pigmented area at the forehead with other hypo-pigmented patches on the face, behind the ear (Figure 1a), at trunk, the scapular area (Figure 1b), dorsum of the hand (Figure 1c), extremities especially dorsum of the foot and upper inner thighs (Figure 1d). The scrotum, flexural areas, creases were spared. No joint swelling or tenderness. His weight was between 3rd and 10th centile, and his height was between 50th and 75th centile. Systemic examination was normal apart from reduced air entry on the right side, mainly the posterior lower zone of the chest. There was no hepatosplenomegaly, bleeding tendency or neurologic or developmental impairment.

A thorough look to the history and examination, raise the possibility of the coexistence of other pathology other than the pneumonia especially that the child remained afebrile despite the worsening chest X-ray. Therefore, prompt investigations were ordered.

Preliminary investigation revealed anemia with elevated acute phase reactant. The relevant hematological findings were hemoglobin of 8.8 gm%, total white cell count was within normal range of healthy population with no leucopenia, neutropenia or lymphopenia. The total leucocyte count (TLC) 11900/μl, platelet count 531000/μl. Differential leucocyte counts showed 60% lymphocytes, 26% neutrophils, 10% monocytes and eosinophils 4%. C-reactive protein (CRP): 12 mg/l.

T-Spot Tuberculosis test: non-reactive. Acid fast bacilli (AFB) Smear only: AFB not seen. AFB culture and sensitivity (gastric aspirate): not seen.

X-ray chest showed right middle lobe consolidation. Repeated chest X-ray after one week revealed patchy opacities, noted in the Right lung and Left lower lobe suggestive of progressive pneumonic consolidation.

Immune status screen showed nonspecific reactive picture. Immunoglobulins assay showed elevated immunoglobulin E (IgE) 2680.0 KU/L (N: 0-64). Liver and renal function test were normal.

The characteristic feature in the peripheral blood film was the existence of several abnormal large granules in the cytoplasm of neutrophils and eosinophilis (Figure 2a). Large round to oval azurophilic cytoplasmic granule in few lymphocytes was observed (Figure 2b). Platelets show mild reactive thrombocytosis. WBCs morphology is highly suggestive of Chediak-Higashi Syndrome.

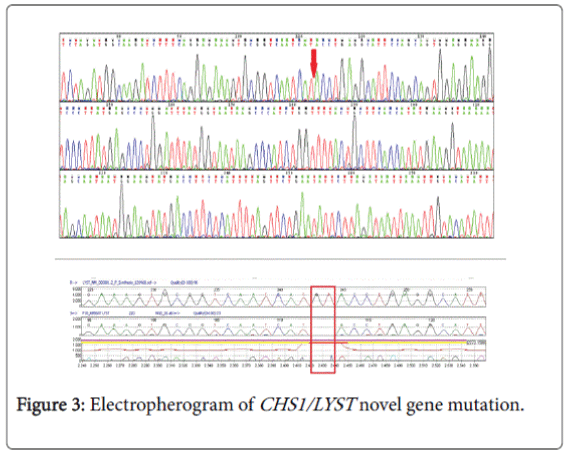

Genetic study (CHS1/LYST gene) (Figure 3) was done by the following method: the coding regions and intronic flanking regions (±8 bp) of the LYST gene (NM_000081.3; chr.1) were completely sequenced in this test. The test is performed by oligonucleotide-based target capture (QXT, Agilent Technologies) followed by next generation sequencing (MiSeq, Illumina). Alignment and variant calls were generated using the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA, MiSeq reporter) followed by NextGENe (Soft Genetics) analysis. Where necessary, Sanger sequencing was used to provide data for bases with insufficient coverage (mean coverage under 100X and/or minimum coverage of less than 20X). Independent Sanger sequencing confirmed all clinically significant and novel variants.

Normal variants (polymorphisms) previously reported in the literature and/or listed on dbSNP and found on this test are not reported. The gene study showed an apparently homozygous c. 6159_6160del (p.Met2053Ilefs*31) variant was detected in the LYST gene. This result confirms the clinical diagnosis of Chediak-Higashi syndrome caused by mutations in the LYST gene. This novel variant has not been previously described in the literature. However, since it is predicted to create a premature stop codon (p.Met2053Ilefs*31), and therefore to produce a truncated LYST protein, it is most likely a disease-causing mutation.

The child was started on empirical antibiotic until the results of sputum culture, which showed Hemophilus influenza and Pseudomonas aeruginosa , so the child was treated according to culture sensitivity

Parents were instructed about the important measures to prevent routine infections including meticulous attention to oral and dental care, and skin protection and sunglasses to prevent sunburn.

The child remained stable, repeated CXR showed possible cavity on the right lower lobe, advised for CT scan but his father disagreed. The child was discharged prematurely against medical advice. On receiving the report of gene testing, the parents were advised to do testing for homozygosity. Genetic counselling for patient/parents and at-risk relatives was recommended.

Human leucocytic antigen (HLA) testing was done for the parents and siblings for possible bone marrow transplantation.

Discussion

Chediak-Higashi syndrome is a disease of infancy and early childhood. CHS is a rare autosomal recessive disorder characterized by oculocutaneous albinism of variable degrees, recurrent pyogenic infections, a tendency for mild bleeding, and neurologic dysfunction which appears later in life.

Our patient presented with pneumonia. An interesting aspect of our patient was the absence of recurrent infections or any other clinical stigmata apart from eczema and anemia. Our patient cannot be considered as partial albinism, he had scattered areas of hypo and hyperpigmentation. It was previously reported by Fukai et al. [5], a case with CHS with hyperpigmentation area on the face. This finding could be attributed to failure of degradation of melanosomes or melanosomes complexes. Moreover, this finding might be due to constitutional increase in tyrosinase activity in dark skin population which led to increase pigmentation of exposed areas [6]. On the contrary, our patient, his parents and siblings were not of the dark skin population.

The presence of right lobe pneumonia with loss of weight according to the mother, in addition to the history of exposure to house cleaner with old Tuberculosis made us to consider possible tuberculosis which became remote possibility by the negative tuberculin , negative T-spot test , AFB Smear only and negative AFB culture and sensitivity (gastric aspirate). The presence of hypopigmentation and hyperpigmentation with skin eczema raised the possibility of xeroderma pigmentosa where the child develops freckling of the skin in the sun exposed. On the contrary, our child’ skin color was medium fair with areas of hyperpigmentation on the forehead and hypopigmentated macules; behind the ear on the chest wall, at the scapular area and dorsum of the hand and foot. The possibility of immune deficiency was considered since the child remained afebrile with worsening of the chest x-ray and presence of pseudomonas aeuroginosa in the sputum culture. This organism has become an important cause of infection in immunocompromised hosts. Immune status and immunoglobulins as well as Band T lymphocytes were all normal. The differentials of CHS, namely Griscelli syndrome type 2, Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome type 2 were excluded by the presence of abnormal azurophilic granules in neutrophilis, eosinophilis and lymphocytes, which is hallmark of CHS.

The most striking abnormality in our case was azurophilic granules in neutrophils, eosinophils and lymphocytes, which is a characteristic of CHS. On the other hand, peripheral blood examination for both parents and siblings revealed no similar granules.

In 1996, the genetic defect that results in CHS was recorded [2,3], and mapped to human chromosome 1q42–44. The human gene, CHS1 , for lysosomal trafficking regulator gene was previously called LYST (LYST, OMIM #606897).

The mutation of murine gene for beige, is about 87.9% homologus with LYST in human CHS mouse model [2,7]. The gene which includes 53 exons (51 coding) with a reading open frame of 11,406 bp, and encodes for a 3801 amino acid protein, is CHS1. The CHS1 protein is a highly conserved, large cytosolic protein of approximately 430 kDa. Several ARM/HEAT α-helix repeats of N-terminal extreme followed by a BEACH domain and a C-terminal domain of seven WD40 repeats. To date, the CHS1 exact function is still unknown. It is anticipated to have a role in regulating size, fission, and secretion of lysosome-related organelle [8].

Molecular diagnosis is challenging and cumbersome because of the sheer size of the gene. In our case the genetic (CHS1/LYST gene); testing revealed homozygous c.6159_6160 del (p.Met2053Ilefs*31) variant in the LYST gene. This is a novel variant genotype of CHS which was not reported in any literature till date. Clinical CHS phenotypes correlate with molecular genotypes. CHS patients with deletions in the LYST gene usually present with a fulminant accelerated phase early in life, whereas, those with missense mutations have a better prognosis, characterized by the absence of an accelerated phase and no neurological involvement [9]. It is critical to differentiate patients who present with the mild form of disease to enroll them into a transplantation protocol, which is the only curative treatment.

The parents were explained about the importance of testing for homozygosity. Genetic counselling for patient/parents and at-risk relatives was recommended. Parents and siblings were subjected for Human leucocytic antigen (HLA) testing for possible bone marrow transplantation.

References

- Kaplan J, De Domenico I, Ward DM (2008)Chediak-Higashi syndrome. Current Opinion in Hematology 15: 22-29.

- Barbosa MD, Nguyen QA, Tchernev VT, Ashley JA, Detter JC, et al. (1996) Identification of the homologous beige and chediakhigashi syndrome genes Nature 382: 262-265.

- Nagle DL, Karim MA, Woolf EA, Holmgren L, Bork P, et al. (1996) Identification and mutation analysis of the complete gene for Chediak-Higashi syndrome Nat Genet 14:307-311.

- Janka GE (2012) Familial and acquired hemophagocyticlymphohistiocytosis. Eur J Pediatr 166:95-109.

- Fukai K, Ishii M, Kadoya A, Chanoki M, Hamada T (1993) Chediak-Higashi syndrome: report of a case and review of the Japanese literature. J Dermatol20: 231-237.

- Singh A, Bryan MM, Roney JC, Cullinane AR, Gahl WA, et al. (2015) A clinical report of Chediak–Higashi syndrome in infancy with a novel genotype from the Indian subcontinent. Int J Dermatol 55: 317-321.

- Perou CM, Moore KJ, Nagle DL, Misumi DJ, Woolf EA, et al. (1996) Identification of the murine beige gene by YAC complementation and positional cloning. Nat Genet 13:303-308.

- Durchfort N, Verhoef S, Vaughn MB, Shrestha R, Adam D, et al. (2012) The enlarged lysosomes in beige j cells result from decreased lysosome fission and not increased lysosome fusion. Traffic 13:108-119.

- Westbroek W, Adams D, Huizing M, Koshoffer A, Dorward H et al. (2007) The severity of cellular defects in Chediak–Higashi syndrome correlate with the molecular genotype and clinical phenotype. Invest Dermatol127: 2674-2677.

Relevant Topics

- Constipation

- Digestive Enzymes

- Endoscopy

- Epigastric Pain

- Gall Bladder

- Gastric Cancer

- Gastrointestinal Bleeding

- Gastrointestinal Hormones

- Gastrointestinal Infections

- Gastrointestinal Inflammation

- Gastrointestinal Pathology

- Gastrointestinal Pharmacology

- Gastrointestinal Radiology

- Gastrointestinal Surgery

- Gastrointestinal Tuberculosis

- GIST Sarcoma

- Intestinal Blockage

- Pancreas

- Salivary Glands

- Stomach Bloating

- Stomach Cramps

- Stomach Disorders

- Stomach Ulcer

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 11960

- [From(publication date):

August-2016 - Aug 19, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 11041

- PDF downloads : 919