Degrees of Recommendations and Levels of Evidence: What you Need to Know?

Received: 05-Nov-2015 / Accepted Date: 19-Jan-2016 / Published Date: 26-Jan-2016 DOI: 10.4172/2471-9919.1000101

Abstract

Clinical practice guidelines and other recommendations need to be used based on how much confidence can be placed in its recommendations. Systematic and explicit methods to make judgments can reduce errors and improve communication. In this article we present a summary of the practice approach to medicine based on evidence through the degrees of evidence and recommendation levels.

Keywords: Evidence based medicine; Degrees of recommendations; Levels of evidence

41668Introduction

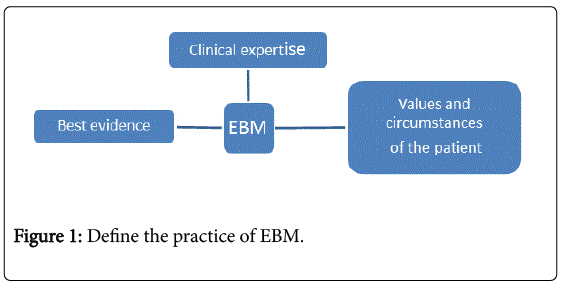

We can define the practice of Evidence-Based Medicine (EBM) as the conscientious, explicit and judicious of the best available evidence in making decisions about care of a patient that requires integration of best evidence with clinical expertise and the values and circumstances of the patient (Figure 1). EBM requires new skills of the clinician, including efficient literature searching, and the application of formal rules of evidence in evaluating the clinical literature [1-16].

This practice basically comprises five steps: A1. Converting the need for information in a question structured; A2. Pursue the best clinical evidence to answer this question; A3. Critically evaluate this evidence with respect to its validity, importance and applicability; A4. Integrate critical appraisal with clinical expertise and with the values and circumstances of the patient; A5. Assess the effectiveness and efficiency in performing the steps above. Steps the EBM processes are presented in Table 1.

| Table 1 | Steps the EBM Process |

|---|---|

| ASSESS the patient | Start with the patient - a clinical problem or question arises from the care of the patient |

| ASK the question | Construct a well-built clinical question derived from the case |

| ACQUIRE the evidence | Select the appropriate resource(s) and conduct a search |

| APPRAISE the evidence | Appraise that evidence for its validity (closeness to the truth) and applicability (usefulness in clinical practice) |

| APPLY talk with the patient | Return to the patient - integrate that evidence with clinical expertise, patient preferences and apply it to practice |

Table 1: Steps in the EBM process.

The classification of the grade of recommendation corresponds to the strength of scientific evidence of the work and its main objectives: to provide transparency to the origin of the information, stimulate the search for scientific evidence of force majeure, introduce a didactic and simple way to help critical evaluation of the player, who bears the responsibility for making the decisions the patient being treated [2]. The degrees of recommendations are shown in Table 2.

| Table 2 | Grades of Recommendation |

|---|---|

| A | Directly based on Level I evidence |

| B | Directly based on Level II evidence or extrapolated recommendations from Level I evidence |

| C | Directly based on Level III evidence or extrapolated recommendations from Level I or II evidence |

| D | Directly based on Level IV evidence or extrapolated recommendations from Level I, II, or III evidence |

Table 2: The degrees of recommendations. Data extrapolation can use in a situation that is potentially clinically important differences than the original study situation.

Levels of Evidence

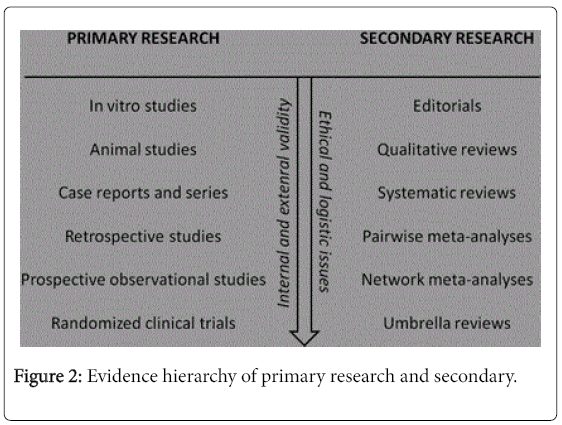

Guidelines can deal with clinical issues such as diagnosis, prognosis, intervention, etiology and tracking. With this different research projects are developed, and consequently requires different hierarchies of evidence that recognize the importance of research designs relevant to the purpose of the guideline. Levels of evidence are presented in Figure 2 [2,16-22].

Clinical trials are given to evaluate the safety and efficacy:

(1) A new product

(2) A new formulation of the same product or combination of products already in use

(3) A new clinical indication for a product already approved.

The assays can evaluate the therapeutic or prophylactic effect. Studies on the etiology are used in order to analyse the probable causes of the various types of diseases. When the perpetrators are discovered (or cause) of a specific disease, these are called "etiologic agents," precisely because they are the bodies responsible for development of a given pathology. Studies of harm are used to verify the effects of harmful agents on the important outcomes for patients [2].

| Table 3 | TPEH |

|---|---|

| IA | Systematic reviews (with homogeneity) of randomized controlled trials. |

| IB | Individual randomized controlled trials (with narrow confidence interval). |

| IC | All or none randomized controlled trials. |

| IIA | Systematic reviews (with homogeneity) of cohort studies |

| IIB | Individual cohort study or low quality randomized controlled trials (e.g. <85% follow-up). |

| IIC | "Outcomes" Research; ecological studies. |

| IIIA | Systematic review (with homogeneity) of case-control studies. |

| IIIB | Case-control study. |

| IV | Case-series (and poor quality cohort and case-control studies) |

| V | Expert opinion without explicit critical appraisal, or based on physiology, bench research or “first principles” |

Table 3: Levels of evidence for therapy, prevention, etiology and harm.

Diagnostic tests are invaluable tools used to distinguish between patients having a disease and those who have not. It is essential to be able to critically appraise published articles on a diagnostic test. The list of questions below can help you better appreciate and understand the diagnostic studies better [2]. Table 4 describes the levels of evidence for diagnosis.

| Table 4 | Diagnosis |

|---|---|

| IA | Systematic review (with homogeneity) of Level 1 diagnostic studies; or a clinical decision rule with 1b studies from different clinical centers. |

| IB | Validating cohort study with good reference standards; or clinical decision rule tested within one clinical center |

| IC | Absolute SpPins And SnNouts (An Absolute SpPin is a diagnostic finding whose Specificity is so high that a Positive result rules-in the diagnosis. An Absolute SnNout is a diagnostic finding whose Sensitivity is so high that a Negative result rules-out the diagnosis). |

| IIA | Systematic review (with homogeneity) of Level>2 diagnostic studies |

| IIB | Exploratory cohort study with good reference standards; clinical decision rule after derivation, or validated only on split-sample or databases |

| IIIA | Systematic review (with homogeneity) of 3b and better studies |

| IIIB | Non-consecutive study; or without consistently applied reference standards |

| IV | Case-control study, poor or non-independent reference standard |

| V | Expert opinion without explicit critical appraisal, or based on physiology, bench research or "first principles" |

Table 4: Levels of evidence.

Prognosis can be defined as the prediction of the future course of a disease after its installation. Patient groups are listed accompanied in time to measure their clinical outcomes [2]. Table 5 describes the levels of evidence for Prognosis.

| Table 5 | Prognosis |

|---|---|

| IA | Systematic review (with homogeneity) of inception cohort studies; or a clinical decision rule validated in different populations |

| IB | Individual inception cohort study with > 80% follow-up; or a clinical decision rule validated on a single population |

| IC | All or none case-series |

| IIA | Systematic review (with homogeneity) of either retrospective cohort studies or untreated control groups in randomized controlled trials. |

| IIB | Retrospective cohort study or follow-up of untreated control patients in a randomized controlled trial; or derivation of a clinical decision rule or validated on split-sample only |

| IV | "Outcomes" research |

| V | Expert opinion without explicit critical appraisal, or based on physiology, bench research or "first principles" |

Table 5: Levels of evidence for prognosis.

Studies on the differential diagnosis are used in patients with a particular clinical presentation to set the frequency of adjacent disturbances [2]. Table 6 describes the levels of evidence for differential diagnosis / symptom prevalence study.

| Table 6 | Differential diagnosis / symptom prevalence study |

|---|---|

| IA | Systematic reviews (with homogeneity) of prospective cohort studies |

| IB | Prospective cohort study with good follow-up |

| IC | All or none randomized controlled trials. |

| IIA | Systematic reviews (with homogeneity) of 2b and better studies |

| IIB | Retrospective cohort study or poor follow-up. |

| IIC | Ecological studies. |

| IIIA | Systematic review (with homogeneity) of 3b and better studies |

| IIIB | Non-consecutive cohort study, or very limited population |

| IV | Case-series or superseded reference standards |

| V | Expert opinion without explicit critical appraisal, or based on physiology, bench research or “first principles”. |

Table 6: Levels of evidence for differential diagnosis / symptom prevalence study.

Economic analysis is a systematic and comparative assessment of the costs and consequences of two or more alternative treatments or programs of action for the promotion and health care. The basic function of an economic analysis is to identify, quantify, assess and compare the costs and consequences of alternatives considered for promotion and health care. The decision analysis to compare two or more decision options and this process involves identifying all available management options, and potential outcomes of each of a series of decisions that have to be made about patient care [2]. Table 7 describes the levels of evidence for Economic and decision analyses.

| Table 7 | Economic and Decision Analysis |

|---|---|

| IA | Systematic reviews (with homogeneity) of Level 1 economic studies |

| IB | Analysis based on clinically sensible costs or alternatives; systematic review(s) of the evidence; and including multi-way sensitivity analyses |

| IC | Absolute better-value or worse-value analyses |

| IIA | Systematic reviews (with homogeneity) of Level >2 economic |

| IIB | Analysis based on clinically sensible costs or alternatives; limited review(s) of the evidence, or single studies; and including multi-way sensitivity analyses |

| IIC | Audit or outcomes research |

| IIIA | Systematic review (with homogeneity) of 3b and better studies |

| IIIB | Analysis based on limited alternatives or costs, poor quality estimates of data, but including sensitivity analyses incorporating clinically sensible |

| IV | Analysis with no sensitivity analysis |

| V | Expert opinion without explicit critical appraisal, or based on economic theory or “first principles” |

Table 7: Levels of evidence for economic and decision analyses.

In conclusion, the conscious use of specific best evidence in making decisions, and the use of levels of evidence and grades of recommendations can benefit the patient and improve their clinical practice.

References

- Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group (1992) Evidence-based medicine. A new approach to teaching the practice of medicine. JAMA 268: 2420-2425.

- Guyatt G, Meade MO, Cook DJ, Rennie D (2014) Users' Guides to the Medical Literature: A Manual for Evidence-based Clinical Practice, Third edition. New York.

- Sackett DL, Richardson WS, Rosemberg WS, Rosenberg W, Haynes BR (1997) Evidence-Based Medicine: how to practice and teach EBM. Churchill Livingstone.

- Bligh J (1995) Problem-based learning in medicine: an introduction. Postgrad Med J 71: 323-326.

- Guyatt GH, Sackett DL, Cook DJ (1993) Users' guides to the medical literature. II. How to use an article about therapy or prevention. A. Are the results of the study valid? Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA 270: 2598-2601.

- Guyatt GH, Sackett DL, Cook DJ (1994) Users' guides to the medical literature. II. How to use an article about therapy or prevention. B. What were the results and will they help me in caring for my patients? Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA 271: 59-63.

- Jaeschke R, Guyatt G, Sackett DL (1994) Users’ guides to the medical literature. III. How to use an article about a diagnostic test. A. Are the results of the study valid? JAMA 271: 389-391.

- Jaeschke R, Guyatt GH, Sackett DL (1994) Users' guides to the medical literature. III. How to use an article about a diagnostic test. B. What are the results and will they help me in caring for my patients? The Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA 271: 703-707.

- Levine M, Walter S, Lee H, Haines T, Holbrook A, et al. (1994) Users' guides to the medical literature. IV. How to use an article about harm. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA 271: 1615-1619.

- Laupacis A, Wells G, Richardson WS, Tugwell P (1994) Users’ guides to the medical literature. V. How to use an article about prognosis. JAMA 272: 234-237

- MI (1996) EpidemiologiaClÃnica: ElementosEssenciais. Porto Alegre, ArtesMédicas.

- Friedland DJ (1998) Evidence-Based Medicine: A Framework for Clinical Practice, Appleton & Lange, Stanford, CT.

- Sackett DL, Richardson WS, Rosemberg WS, Rosenberg W, Haynes BR (2005) Evidence-Based Medicine: how to practice and teach EBM. Churchill Livingstone.

- Garg AX, Adhikari NK, McDonald H, Rosas-Arellano MP, Devereaux PJ, et al. (2005) Effects of computerized clinical decision support systems on practitioner performance and patient outcomes: a systematic review. JAMA 293: 1223-1238.

- Guyatt G, Rennie D, Meade MO, Cook DJ (2008) Users´Guides to the Medical Literature.

- Wyer P, Hatala R, Guyatt G (2005) Challenges of teaching EBM. CMAJ. 172: 1424-1425.

- Burns PB, Rohrich RJ, Chung KC (2011) The levels of evidence and their role in evidence-based medicine. PlastReconstr Surg. 128: 305-310.

- Greco T, Biondi-Zoccai G, Saleh O, Pasin L, Cabrini L, et al. (2015) The attractiveness of network meta-analysis: a comprehensive systematic and narrative review. Heart Lung Vessel 7: 133-142.

- Biondi-Zoccai G (2014) Network Meta-analysis: Evidence Synthesis with Mixed Treatment Comparison. Nova Science Publishers, Hauppauge, NY.

- Biondi-Zoccai G, Abbate A , Benedetto U , Palmerini T , D'Ascenzo F, et al. (2015) Network meta-analysis for evidence synthesis: What is it and why is it posed to dominate cardiovascular decision making? International Journal of Cardiology 182: 309–314

Citation: Roever L, Resende ES, Biondi-Zoccai G, Borges ASR (2016) Degrees of Recommendations and Levels of Evidence: What you Need to Know? Evidence Based Medicine and Practice 1: 101. DOI: 10.4172/2471-9919.1000101

Copyright: © 2016 Roever L, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 18949

- [From(publication date): 4-2016 - Jul 09, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 17709

- PDF downloads: 1240