Establishment of Cellular Quiescence Together with H2AX Downregulation and Genome Stability Maintenance

Received: 15-Jan-2018 / Accepted Date: 18-Jan-2018 / Published Date: 22-Jan-2018 DOI: 10.4172/2161-0681.1000335

Abstract

H2AX is required for genome stability. In response to DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs), H2AX is rapidly phosphorylated to form γH2AX foci, which mediate DNA repair and checkpoint signaling. This process is regulated by modifications and molecular interactions of H2AX. In addition, the rapid stabilization of H2AX in response to DSBs facilitates γH2AX foci formation. Although H2AX is markedly downregulated in many cellular states, γH2AX foci can still efficiently form upon DSB generation. Here, we review the regulation of H2AX in response to DSBs.

Keywords: H2AX; γH2AX; DNA double-strand breaks

Abbreviations

DSB: DNA Double-Strand Break; MEF: Mouse Embryonic Fibroblast

Introduction

H2AX mediates repair of DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs), and hence is required for genome stability. In response to DSBs, H2AX is rapidly phosphorylated at Ser139 by ATM, ATR, or DNA-PK, which leads to the generation of γH2AX foci at DSB sites [1,2]. These foci promote DSB repair by non-homologous end joining and/or homologous recombination [3,4]. MDC1 rapidly binds to γH2AX and promotes recruitment of the MRN (MRE11-Rad50-NBS1) complex and ATM. This leads to enlargement of γH2AX foci and amplification of DNA damage signaling, which usually peaks at 30 min after damage [5]. γH2AX foci serve as a platform for the recruitment of DSB repair factors and chromatin-remodeling complexes [6,7]. Monoubiquitination at K119/K120 [8-12] and poly-ubiquitination at K13/K15 [13,14] are also involved in the effective recruitment of many DNA repair-associated factors, such as BRCA1 [15] and 53BP1 [14].

Transient Upregulation of H2AX Efficiently Induces DSB Repair in Quiescent Cells

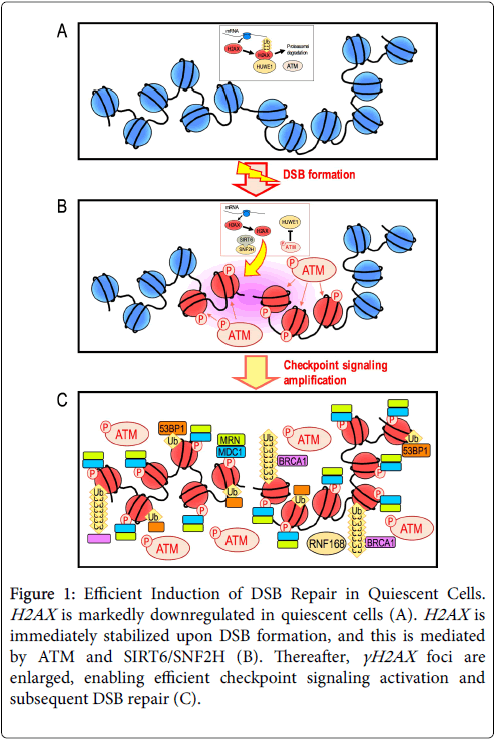

H2AX is a variant of histone H2A. The expression level of H2AX greatly differs between cell types. In particular, H2AX is markedly downregulated in quiescent normal cells [16]. Intriguingly, our recent studies revealed that γH2AX foci efficiently form in response to DSBs even in the H2AX -diminished quiescent state [17]. This is dependent on transient and immediate expression of H2AX upon DSB formation. H2AX is continuously transcribed and translated in non-damaged cells, but undergoes proteasomal degradation mediated by the E3 ubiquitin ligase HUWE1 (Figure 1A) [17]. This proteolytic degradation is immediately blocked after DSB formation and consequently H2AX rapidly accumulates and γH2AX foci efficiently form (Figure 1B).

Figure 1: Efficient Induction of DSB Repair in Quiescent Cells. H2AX is markedly downregulated in quiescent cells (A). H2AX is immediately stabilized upon DSB formation, and this is mediated by ATM and SIRT6/SNF2H (B). Thereafter, γH2AX foci are enlarged, enabling efficient checkpoint signaling activation and subsequent DSB repair (C).

Although the mechanism that regulates this process has not been fully elucidated, it involves SIRT6 and SNF2H for chromatin remodeling and ATM to halt proteasomal degradation [17]. This leads to the recruitment of repair factors in association with additional modifications, including ubiquitination of H2A/H2AX (Figure 1C).

After DSB repair is complete, the cellular H2AX level generally decreases and returns to that observed in the initial quiescent state [17]. Thus, H2AX is markedly downregulated in quiescent cells, but these cells still express H2AX in response to DSBs. However, H2AX is only transiently expressed to efficiently induce DSB repair, and H2AX expression decreases once this repair is complete.

Unlike normal cells, many cancer cells constantly express H2AX , and the H2AX level in these cells is generally 0.1-10% of the total H2A level [2]. However, such cells still demonstrate upregulation of H2AX in response to DSBs in an ATM and a SIRT6/SNF2H-dependent manner [17]. In addition, transient H2AX upregulation is required for efficient DSB repair in H2AX -expressing cancer cells. Thus, transient upregulation of H2AX is a general requirement for the efficient induction of DSB repair [17].

Establishment of Cellular Quiescence with Downregulated H2AX

H2AX is highly expressed in actively growing cells [16], but is usually downregulated in normal cells after serial proliferation. In fact, normal cells generally enter a growth-arrested state with marked downregulation of H2AX in vivo and in vitro [16]. There are several growth-arrested cellular states, including senescence and quiescence, which can be clearly discriminated. The quiescent state is widely established with marked downregulation of H2AX ; H2AX downregulation may directly lead to the acquisition of quiescence because cells enter an identical state upon knockdown of H2AX [16]. In addition, quiescence is associated with organ homeostasis, as demonstrated in normal cells in the liver, spleen and pancreas in vivo [16]. By contrast, senescent cells express some H2AX [16] and contain γH2AX foci, which are usually seen in cells in aging organs and those in a precancerous state [18]. Consistent with these observations in vivo, similar findings were made in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) in vitro . Whereas H2AX is largely downregulated in quiescent MEFs, γH2AX foci form when MEFs become senescent and are subjected to genomic destabilization [16]. Thus, H2AX /γH2AX expression is strongly associated with the establishment of cellular states, i.e., quiescence is established in cells with marked downregulation of H2AX and senescence is established in cells with γH2AX foci.

Importantly, ARF and p53 regulate establishment of the H2AX-downregulated quiescent state [19]. Consequently, this state is abrogated in cells with mutations in ARF or p53, such as cancer cells and immortalized MEFs, in which H2AX expression and growth activity are recovered [19]. Notably, many quiescent cells with downregulated H2AX are protected against transformation. These observations illustrate the importance of the H2AX -diminished cellular state for the protection of cells from the transformation. However, it remains unclear how ARF and p53 regulate the establishment of this state.

Quiescent Cells Are Vulnerable To Replication Stress- Associated DSBs

Quiescent cells can still repair DSBs directly caused by γ-rays via upregulation of H2AX [17], but are vulnerable to replication stressassociated DSBs [20,21]. Replication stress-associated DSBs generally accumulate in quiescent cells exposed to exogenous growth stimuli, and these cells become senescent and often display genomic instability. In addition, senescent MEFs displaying genomic instability further lead to the generation of immortalized MEFs that are mutated in the ARF/p53 module [16,20]. These findings are analogous to cancer development, as cancer development is associated with aging and genomic instability. These results indicate that responses to replication stress-associated DSBs and DSBs directly caused by γ-rays clearly differ; however, the cause of this difference is unknown.

Conclusion

H2AX downregulation is associated with establishment of cellular quiescence, which contributes to homeostasis in many organs. This state is regulated by ARF and p53, and is abrogated by mutation of the ARF/p53 module. Accumulating knowledge illustrates the importance of establishment of the H2AX -downregulated state and maintenance of genome stability in this state. Cells with downregulated H2AX can still repair DSBs directly caused by γ-rays, but are vulnerable to replication stress-associated DSBs caused by continuous exposure to growth stimuli. However, these findings raise a number of further questions. First, what underlies the difference in repair efficiency between DSBs directly caused by γ-rays and DSBs caused by replication stress? Second, how do ARF and p53 regulate establishment of the H2AX -downregulated state? Given that cancers widely develop together with genomic destabilization and mutations in the ARF/p53 module, investigation of these issues may help to prevent cancer.

References

- Stucki M, Jackson SP (2006) gammaH2AX and MDC1: anchoring the DNA-damage- response machinery to broken chromosomes. DNA Repair (Amst) 5: 534-543.

- Bonner WM, Redon CE, Dickey JS, Nakamura AJ, Sedelnikova OA, et al. (2008) GammaH2AX and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 8: 957-967.

- Bassing CH, Alt FW (2004) H2AX may function as an anchor to hold broken chromosomal DNA ends in close proximity. Cell Cycle 3: 149-153.

- Fernandez-Capetillo O, Lee A, Nussenzweig M, Nussenzweig A (2004) H2AX: the histone guardian of the genome. DNA Repair (Amst.) 3: 959-967.

- Rogakou EP, Boon C, Redon C, Bonner WM (1999) Megabase chromatin domains involved in DNA double-strand breaks in vivo. J Cell Biol 146: 905-916.

- Van Attikum H, Gasser SM (2009) Crosstalk between histone modifications during the DNA damage response. Trends Cell Biol 19: 207-217.

- Pinder JB, Attwood KM, Dellaire G (2013) Reading, writing, and repair: the role of ubiquitin and the ubiquitin-like proteins in DNA damage signaling and repair. Front Genet 4: 45.

- Facchino S, Abdouh M, Chatoo W, Bernier G (2010) BMI1 confers radioresistance to normal and cancerous neural stem cells through recruitment of the DNA damage response machinery. J Neurosci 30: 10096-10111.

- Ismail IH, Andrin C, McDonald D, Hendzel MJ (2010) BMI1-mediated histone ubiquitylation promotes DNA double-strand break repair. J Cell Biol 191: 45-60.

- Bentley ML, Corn JE, Dong KC, Phung Q, Cheung TK, et al. (2011) Recognition of UbcH5c and the nucleosome by the Bmi1/Ring1b ubiquitin ligase complex. EMBO J 30: 3285-3297.

- Ginjala V, Nacerddine K, Kulkarni A, Oza J, Hill SJ, et al. (2011) BMI1 is recruited to DNA breaks and contributes to DNA damage-induced H2A ubiquitination and repair. Mol Cell Biol 31: 1972-1982.

- Wu CY, Kang HY, Yang WL, Wu J, Jeong YS, et al. (2011) Critical role of monoubiquitination of histone H2AX protein in histone H2AX phosphorylation and DNA damage response. J Biol Chem 286: 30806-30815.

- Gatti M, Pinato S, Maspero E, Soffientini P, Polo S, et al. (2012) A novel ubiquitin mark at the N-terminal tail of histone H2As targeted by RNF168 ubiquitin ligase. Cell Cycle 11: 2538-2544.

- Mattiroli F, Vissers JH, van Dijk WJ, Ikpa P, Citterio E, et al. (2012) RNF168 ubiquitinates K13-15 on H2A/H2AX to drive DNA damage signaling. Cell 150: 1182-1195.

- Doil C, Mailand N, Bekker-Jensen S, Menard P, Larsen DH, et al. (2009) RNF168 binds and amplifies ubiquitin conjugates on damaged chromosomes to allow accumulation of repair proteins. Cell 136: 435-446.

- Atsumi Y, Fujimori H, Fukuda H, Inase A, Shinohe K, et al. (2011) Onset of Quiescence Following p53 Mediated Down-Regulation of H2AX in Normal Cells. PLoS One 6: e23432.

- Atsumi Y, Minakawa Y, Ono M, Dobashi S, Shinohe K, et al. (2015) ATM and SIRT6/SNF2H Mediate Transient H2AX Stabilization When DSBs Form by Blocking HUWE1 to Allow Efficient γH2AX Foci Formation. Cell Rep 13: 2728-2740.

- Gorgoulis VG, Vassiliou LV, Karakaidos P, Zacharatos P, Kotsinas A, et al. (2005) Activation of the DNA damage checkpoint and genomic instability in human precancerous lesions. Nature 434: 907-913.

- Osawa T, Atsumi Y, Sugihara E, Saya H, Kanno M, et al. (2013) Arf and p53 act as guardians of a quiescent cellular state by protecting against immortalization of cells with stable genomes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 432: 34-39.

- Ichijima Y, Yoshioka K, Yoshioka Y, Shinohe K, Fujimori H, et al. (2010) DNA lesions induced by replication stress trigger mitotic aberration and tetraploidy development. PLoS One 5: e8821.

- Minakawa Y, Atsumi Y, Shinohara A, Murakami Y, Yoshioka K (2016) Gamma-irradiated quiescent cells repair directly induced double-strand breaks but accumulate persistent double-strand breaks during subsequent DNA replication. Genes Cells 21: 789-797.

Citation: Matsuno Y, Torigoe H, Yoshioka K (2018) Establishment of Cellular Quiescence Together with H2AX Downregulation and Genome Stability Maintenance. J Clin Exp Pathol 8: 335. DOI: 10.4172/2161-0681.1000335

Copyright: ©2018 Matsuno Y, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 5867

- [From(publication date): 0-2018 - Nov 27, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 4923

- PDF downloads: 944