Incidence of Child Homicide in the Transkei Sub-Region of South Africa (1996-2014)

Received: 05-May-2018 / Accepted Date: 25-Jun-2018 / Published Date: 30-Jun-2018 DOI: 10.4172/2161-1165.1000345

Abstract

Background: The incidence of child homicide varies from country to country, and also from region to region within the same country. It is always under-researched, therefore under-estimated and under-reported, especially in the rural parts of South Africa.

Objective: To study the incidence of child homicide in the Transkei sub-region of South Africa from 1996 to 2014.

Method: An autopsy record review study at the Forensic Pathology Laboratory at Mthatha for a period of 19 years (1996-2014).

Results: Between 1996 and 2014, over a period of 19 years, 4,713 unnatural deaths were registered in the Transkei sub-region. The average rate of child homicide was 30 per 100,000 of the population of children. The rate of child homicide decreased from 31.8 per 100,000 in 1996 to 23.1 per 100,000 in 2014. The commonest method of homicide was stabbing, with an average rate of 12/100,000. Male child homicide occurred at an average rate of 21/100,000, and female child homicide at an average rate of 9/100,000. The male-to-female ratio is therefore 2.33:1 in this study.

Conclusion: The incidence of child homicide in the Transkei sub-region of South Africa is high. It is a serious matter of concern.

Keywords: Homicide; Murder; Stab injury; Assault; Gunshot

Introduction

Homicide of children is a worldwide problem [1]. Global mortality trends among children and young people have been little studied, even though more than two fifths of the world’s population is aged 5-24 years [2]. About 700 million children are robbed of their lives globally every year [3]. In 1999, about 1,800 juveniles (a rate of 2.6 per 100,000) were victims of homicide in the United States. The rate is substantially higher than that of any other developed country [4]. In 2002, an estimated 53,000 child homicides took place in the world and the highest child homicide rates were observed in sub-Saharan Africa [2].

Violence is widespread in South African society and it has been stated that the prevalence of violence and violence-related injury in the country is among the highest in the world [5]. Homicide rates for South African children were estimated at double the global average in 2000 [6]. A study by the National Injury Mortality Surveillance System (NIMSS) in South Africa, between 2001 and 2005 the child homicide rate in four metropolitan cities was calculated. It showed that the homicide rates were similar to the global pattern, with higher rates for boys and among children aged 0-4 years than for older children [6]. A homicide study in Dar-es-Salaam, in the United Republic of Tanzania, showed a very high rate of early infanticide (27.7 per 100,000 infants less than one week old) but an overall homicide rate among children younger than 15 years of 0.54 per 100,000 [7]. The child homicide rate in South Africa in 2009 was 5.5 per 100,000 children under the age of 18 years, which is double the World Health Organization’s estimated global rate of 2.4 per 100,000, but resembles its estimate for the African region, which is 5.6 per 100,000 of the population of children [8]. A study exploring urban-rural variations in terms of the magnitude and patterns of fatal injuries in South Africa has shown that homicide death rates were significantly higher in urban provinces, while transport-related injury mortality rates were significantly higher in rural provinces [9].

Mortality trends observed in 50 countries in all income categories over a 50-year period (1955 to 2004) clearly point to a progressive rise in violent deaths among young men, a trend that is expected to continue in developing countries [2]. Children may become victims of violence not only because of the use of alcohol and drugs by those within their own homes, but also through the use of such substances by individuals within their social environments, such as parents or peers [10]. Save the Children South Africa released a costing study that showed violence against children in South Africa cost the economy close to R238 billion in gross domestic product in 2015 [11]. Insufficient published literature is available on child homicide, and what is available is old and consequently of little relevance to this study and it offers no opportunity either to compare or contrast information. Therefore, in order to fill this void of information, the purpose of this article is to report findings from a study of the incidence of child homicide in the Transkei sub-region of South Africa and to relate this with age and sex.

Method

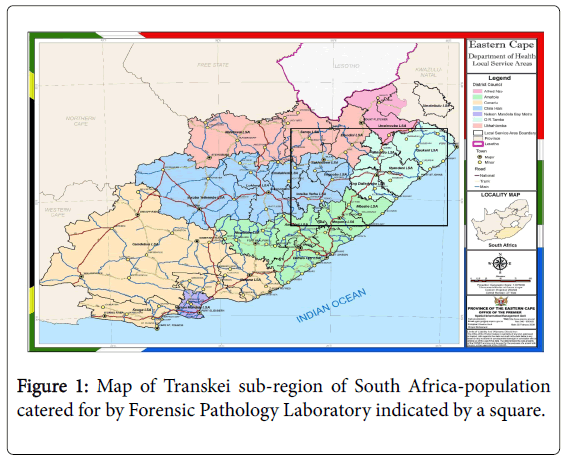

Mthatha Forensic pathology laboratory is the only laboratory in this region catering for more than half a million of the population in the region of Mthatha. Fourteen forensic officers are engaged in collecting corpses round the clock from 17 different police stations in four municipalities in the area, namely OR Tambo, Mhlontlo, Chris Hani and Mbashe municipal area, covering about 200 square kilometers (Figure 1). The OR Tambo municipality is the largest, and covered fully by 10 police stations. Mhlontlo municipality has four police stations, Chris Hani two and Mbashe municipality one.

The laboratory is attached to the Nelson Mandela Academic Hospital, which is the only teaching hospital in this province. This again is attached to Walter Sisulu University Medical School. All medico-legal cases in this region of South Africa are dealt with at this laboratory. In total 23,170 autopsies were conducted there between 1996 and 2014. Details of names, addresses, age, gender, date of autopsy and cause of death were recorded in the post-mortem register.

The child population in the area was 175,636 in 1996, which was 40% of the combined population of 439,091. It has been increasing at an average of 3% annually, reaching 375,933 in 2014. In 2005 there were only five police stations serving the area of this study. The current 14 police stations are an indication of the increase in the population. Population statistics were calculated with the help of the South African Statistics Department in Mthatha. The child population was calculated from the combined population with the help of Statistics of South Africa. According to the records of Statistics South Africa, around 40% of the population in this region are children. It was assumed that the number of children in the combined population would also have shown an annual increase of 3%. All children of 18 and below were included in this study. The autopsy records included 79 children for whom no age was given or the cause of death could not be determined. They were excluded from this study. Only cases of stab injury, blunt trauma (assault) and firearm (gunshot) wounds were taken into account in this study. These three external causes of homicide were combined from 1996 to 2014 and the rate per 100,000 of the population was calculated. Data were collected on a paper sheet designed to reflect the post mortem examination number, year, gender, and cause of death. These data were transfer to an Excel computer program, and analyzed using the SPSS computer program.

Results

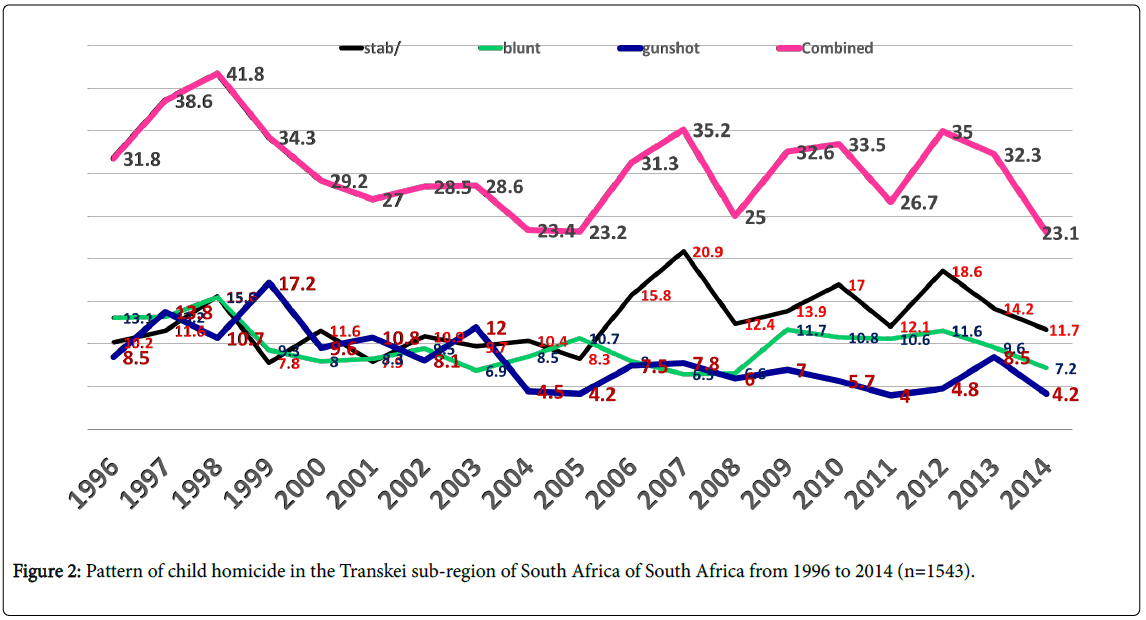

Between 1996 and 2014, a period of 19 years, 4,713 unnatural deaths were registered in the Transkei sub-region (Table 1). The average rate of child homicide in that time was 30 per 100,000 of the population of children (Table 2). The rate of child homicide decreased from 31.8 per 100,000 in 1996 to 23.1 per 100,000 in 2014. The highest rate (41.8/100,000) of homicide was recorded in 1998, and the lowest (23.1/100,000) in 2014. The commonest method of homicide was stabbing, with an average rate of 12/100,000 followed by blunt force trauma at an average of 10/100,000 and gunshot wounds at an average rate of 8/100,000 of the population of children in this study. The rate of murder by stabbing increased from 10.2/100,000 in 1996 to 11.7/100,000 in 2014, with the highest rate of death (20.9/100,000) recorded in 2007 and the lowest (7.8/100,000) in 1999 in this study. Death as a result of blunt force trauma decreased from 13.1 to 7.2 per 100,000 of the population over the period of 19 years (Table 2 and Figure 2). The number of gunshot injury deaths decreased from 8.5/100,000 in 1996 to 4.2/100,000 in 2014. The highest rate of gunshot-related homicide was 17.2/100,000 which was recorded in 1999, and the lowest was 4/100,000 which was recorded in 2011 (Table 2 and Figure 2).

| Ranks | Cause of deaths | 1-5 year (%) | 6-10 year (%) | 11-15 year (%) | 16-18 year (%) | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MVA | 271 (5.75) | 372 (7.9) | 295 (6.26) | 311(6.6) | 1249 (26.52) |

| 2 | Stab | 39 (0.82) | 26 (0.55) | 130 (2.71) | 476 (10.11) | 671 (14.20) |

| 3 | drowning | 185 (3.92) | 191(4.05) | 156 (3.31) | 78 (1.65) | 610 (12.95) |

| 4 | Blunt trauma | 38 (0.80) | 30 (0.63) | 111 (2.35) | 308 (6.52) | 487 (10.32) |

| 5 | Gunshot | 26 (0.55) | 39 (0.82) | 111 (2.35) | 209 (4.39) | 385 (8.13) |

| 6 | Hanging | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 107 (2.27) | 148 (3.14) | 255 (5.41) |

| 7 | Lightning | 27 (0.57) | 40 (0.84) | 68 (1.44) | 74 (1.57) | 209 (4.43) |

| 8 | burns | 100 (2.12) | 35 (0.74) | 26 (0.55) | 35 (0.74) | 196 (4.16) |

| 9 | Fell | 40 (0.84) | 32 (0.67) | 54 (1.14) | 30 (0.63) | 156 (3.31) |

| 10 | poisoning | 46 (0.97) | 15 (0.31) | 74 (1.57) | 135 (2.86) | 270 (5.73) |

| 11 | Collapse | 35 (0.74) | 23 (0.48) | 39 (0.82) | 58 (1.23) | 155 (3.29) |

| 12 | Decomposition | 16 (0.33) | 4 (0.08) | 6 (0.12) | 9 (0.19) | 35 (0.74) |

| 13 | Gas | 17 (0.36) | 5 (0.10) | 3 (0.06) | 10 (0.21) | 35 (0.74) |

| All | All causes of death | 849 (18.03) | 823 (17.48) | 1158 (24.59) | 1883 (39.9) | 4713 (100) |

Table 1: Percentage of cause of death among both genders in different age groups in the Transkei sub-region of South Africa (1996-2014).

| Year | Children population |

Stab injury (n=671) | Stab/100,000 | Blunt trauma (n=487) | Blunt/100,000 | Gunshot (n=385) | Gunshot/100,000 | Both Sex child homicide (n=1543) | Both sex child homicide per 100,000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996 | 175636 | 18 | 10.2 | 23 | 13.1 | 15 | 8.5 | 56 | 31.8 |

| 1997 | 180905 | 21 | 11.6 | 24 | 13.2 | 25 | 13.8 | 70 | 38.6 |

| 1998 | 186332 | 29 | 15.6 | 29 | 15.5 | 20 | 10.7 | 78 | 41.8 |

| 1999 | 191922 | 15 | 7.8 | 18 | 9.3 | 33 | 17.2 | 66 | 34.3 |

| 2000 | 197680 | 23 | 11.6 | 16 | 8 | 19 | 9.6 | 58 | 29.2 |

| 2001 | 203610 | 16 | 7.9 | 17 | 8.3 | 22 | 10.8 | 55 | 27 |

| 2002 | 209719 | 23 | 10.9 | 20 | 9.5 | 17 | 8.1 | 60 | 28.5 |

| 2003 | 216010 | 21 | 9.7 | 15 | 6.9 | 26 | 12 | 62 | 28.6 |

| 2004 | 222490 | 23 | 10.4 | 19 | 8.5 | 10 | 4.5 | 52 | 23.4 |

| 2005 | 288121 | 24 | 8.3 | 31 | 10.7 | 12 | 4.2 | 67 | 23.2 |

| 2006 | 296765 | 47 | 15.8 | 24 | 8 | 22 | 7.5 | 93 | 31.3 |

| 2007 | 305668 | 64 | 20.9 | 20 | 6.5 | 24 | 7.8 | 108 | 35.2 |

| 2008 | 314838 | 39 | 12.4 | 21 | 6.6 | 19 | 6 | 79 | 25 |

| 2009 | 324283 | 45 | 13.9 | 38 | 11.7 | 23 | 7 | 106 | 32.6 |

| 2010 | 334012 | 57 | 17 | 36 | 10.8 | 19 | 5.7 | 112 | 33.5 |

| 2011 | 344032 | 42 | 12.1 | 36 | 10.6 | 14 | 4 | 92 | 26.7 |

| 2012 | 354353 | 67 | 18.6 | 39 | 11.6 | 17 | 4.8 | 123 | 35 |

| 2013 | 364984 | 53 | 14.2 | 34 | 9.6 | 32 | 8.5 | 119 | 32.3 |

| 2014 | 375933 | 44 | 11.7 | 27 | 7.2 | 16 | 4.2 | 87 | 23.1 |

| Mean | 267752 | 35 | 12 | 26 | 10 | 20 | 8 | 81 | 30 |

Table 2: Incidence of MVA in the Mthatha area of South Africa by gender (1993–2015) (n=6 620).

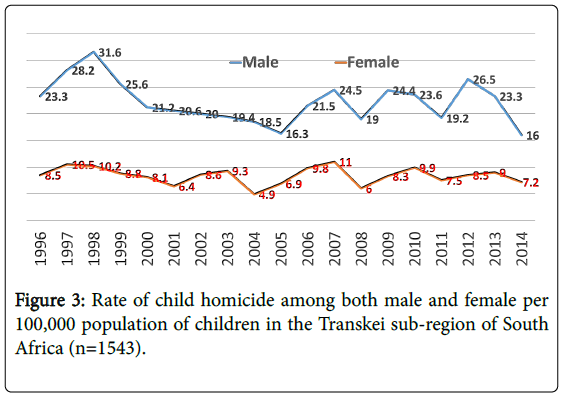

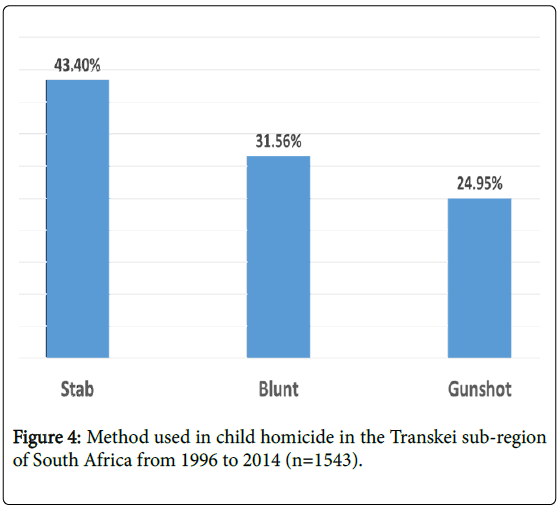

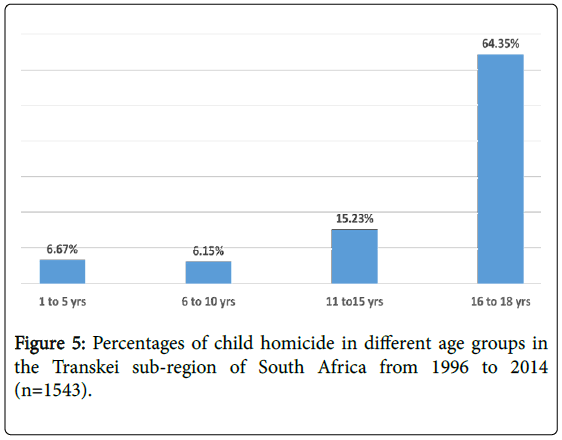

Male child homicide occurred at an average rate of 21/100,000 and female child homicide at an average rate of 9/100,000 (Table 3 and Figure 3). The male-to-female ratio is therefore 2.33:1 in this study. There has been a decrease in male child homicide from 23.3/100,000 to 16/100,000 and in female child homicide from 8.5 to 7.2 per 100,000 (Table 3 and Figure 3). Stabbing accounted for 43.4% of cases, followed by blunt trauma at 31.56%, and gunshot wounds at 24.95% (Table 4 and Figure 4). The age group affected most often was 16 to 18 years of age in 64.35% of cases, followed by the group between 11 and 15 years in 15.23%, the one between 6 and 10 years in 6.15% and the one between 1 and 5 years in 6.67% of cases (Table 4 and Figure 5).

| Year | Children population | No. male children (n=1118) | Male child homicide /100,000 | No. Female children (n=425) | Female child homicide/100,000 | Total number of children (n=1543) | Total child homicide/100,000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996 | 175636 | 41 | 23.3 | 15 | 8.5 | 56 | 31.9 |

| 1997 | 180905 | 51 | 28.2 | 19 | 10.5 | 70 | 38.7 |

| 1998 | 186332 | 59 | 31.6 | 19 | 10.2 | 78 | 41.8 |

| 1999 | 191922 | 49 | 25.6 | 17 | 8.8 | 66 | 34.4 |

| 2000 | 197680 | 42 | 21.2 | 16 | 8.1 | 58 | 29.3 |

| 2001 | 203610 | 42 | 20.6 | 13 | 6.4 | 55 | 27 |

| 2002 | 209719 | 42 | 20 | 18 | 8.6 | 60 | 28.6 |

| 2003 | 216010 | 42 | 19.4 | 20 | 9.3 | 62 | 28.7 |

| 2004 | 222490 | 41 | 18.5 | 11 | 4.9 | 52 | 23.4 |

| 2005 | 288121 | 47 | 16.3 | 20 | 6.9 | 67 | 23.2 |

| 2006 | 296765 | 64 | 21.5 | 29 | 9.8 | 93 | 31.3 |

| 2007 | 305668 | 75 | 24.5 | 33 | 11 | 108 | 35.3 |

| 2008 | 314838 | 60 | 19 | 19 | 6 | 79 | 25 |

| 2009 | 324283 | 79 | 24.4 | 27 | 8.3 | 106 | 32.7 |

| 2010 | 334012 | 79 | 23.6 | 33 | 9.9 | 112 | 33.5 |

| 2011 | 344032 | 66 | 19.2 | 26 | 7.5 | 92 | 26.7 |

| 2012 | 354353 | 94 | 26.5 | 30 | 8.5 | 124 | 35 |

| 2013 | 364984 | 85 | 23.3 | 33 | 9 | 118 | 32.3 |

| 2014 | 375933 | 60 | 16 | 27 | 7.2 | 87 | 23.2 |

| average | 267752 | 58.84 | 21 | 22.36 | 9 | 81.2 | 30 |

Table 3: Incidence of child homicide in both sex in the Transkei sub-region of South Africa from 1996 to 2014 (n=1543).

| Cause of child homicide | 1-5 years (%) | 6-10 years (%) | 11-15 years (%) | 16-18 years (%) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stab | 39 (2.52) | 26(1.68%) | 130(8.42) | 476 (30.84) | 671 (43.4%) |

| Blunt trauma | 38 (2.46) | 30 (1.94) | 111(7.19) | 308(19.96) | 487(31.56) |

| Gunshot | 26(1.68) | 39(2.52) | 111(7.19) | 209(13.54) | 385 (24.95) |

| All causes of homicide | 103(6.67) | 95(6.15) | 235 (15.23) | 993 (64.35) | 1543 (100) |

Table 4: Child homicide in different age groups with different type of methods used from 1996 to 2014 in the Transkei region of South Africa (n=1543).

Discussion

Child homicide is under-investigated and therefore under-reported. Only one third of all child deaths resulting from child abuse are classified as homicides [12]. This is probably the first rural-based study in South Africa with such a large sample size and covering a period of 19 years, that addresses the problem of child homicide in the country. There is hardly any effort to stop these killing in most countries, especially in developing countries.8 Thousands of children are victims of homicide annually, despite the right to protection and care afforded under the United Nations Convention on the Right of the Child [8].

Out of 13 causes of death among children in this region, except for drowning, the first five were related with trauma (Table 1). More than one fourth (26.5%) of children died as a result of motor vehicle accidents (Table 1). About one-third (32.7%) of all the unnatural deaths of children in the Transkei sub-region of South Africa (Table 1) were child homicides. The number of child homicide cases UNICEF documented in South Africa were 965 in 2009, 906 in 2010 and 793 in 2011.10 Based on this report, child homicide in the Transkei subregion is estimated as representing 10% (2009), 12% (2010) and 11.6% (2011) of all South African homicide in the respective years, according to a UNICEF report10 published in 2012 (Table 2). This region, which was in many ways separated from the rest of the country during the apartheid years, does not seem to value human life highly. The people in the region engage in elaborate funeral rituals on the death of a child, without paying much attention to the manner of death. The annual rate of child homicide of 30 per 100,000 of the child population is not even prevalent in countries where serious war is going on, such as Iraq, Afghanistan and Syria, despite the fact that the Transkei is not declared as a war zone (Table 2 and Figure 2). In total 1,159 children were killed between January and June 2017 in a population of 19 million in Syria. This means that a child homicide rate of 12.2 per 100,000 could be estimated in Syria, where fierce fighting has been going on for the last seven years [13]. It means the rate of child homicide in the Transkei sub-region is more than twice as high as the death rate of children in Syria (Table 2 and Figure 2). The rate of child homicide in this study is more than five times the African estimate of child homicide in 2009, which was 5.6 per 100,000 children under the age of 18 years.8 The global rate of child homicide is 2.4 per 100,000 of the population of children, which is far less than the rate in the Transkei sub-region of South Africa [8].

There has been a significant (31.8 vs. 23.1/100,000) decrease in the child homicide rate over a period of 19 years (1996-2014) (Table 2 and Figure 2), probably because of the implementation of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child [8]. The drop in the number of deaths as a result of gunshot injuries and blunt force trauma has contributed most to this decrease (Table 2 and Figure 2). The number of deaths caused by gunshot injuries has reduced by more than half, i.e. from 8.5 to 4.2 per 100,000, and those caused by blunt force trauma from 13.1 to 7.2 per 100,000 of the child population (Table 2 and Figure 2). In a recent publication titled ‘Where have all the guns gone?’ Matzopoulos et al. (2016) pointed out the effect of the implementation of the Gun Control Act of 2002. There has been a steadily decreasing trend in gunshot-related death, a decrease of 60% from the peak of 2000 [14]. Three million firearm owners are registered in South Africa. The number of illegal firearms has been reduced by at least 24% since the Firearm Control Act was implemented in 2004 [15].

However, child homicide as a result of penetrating injuries caused by sharp objects neutralized this positive gain to certain extent, since the number of such injuries increased in the same period, from 10.2 to 11.7 per 100,000 of the population of children (Table 2 and Figure 2). This shows the mindset of the Transkeian people. There is a culture of violence in this region. It is difficult to understand the factors that propagate this culture. Poverty is commonly blamed for this violence, but it is not the sole reason for the high violence. It may contribute in violence significantly, although there is no evidence to claim as hardly any study conducted on economic impact and crime. Most (46.6%) black Africans live in poverty. The poorest of the poor currently live on R531 per month and spend nearly 30 percent of this amount on food every month [16].

Among male children the homicide rate is more than twice (21 per 100,000) higher than among female children (9/100,000) in this study (Table 3 and Figure 3). The rate of homicide is always distinctly different in males and females especially on deaths as a result of trauma. A recent (2017) study carried out by the author on unnatural deaths in the Transkei showed similar figures, i.e. the rate of death was 160 per 100,000 among males and 44 per 100,000 among females [17]. Teenage boys were victims of homicide five times more often than teenage girls [18]. Among male children the rate of homicide decreased significantly, i.e. from 23.3/100,000 to 16/100,000, while among females it fell only very marginally, i.e. from 8.5/100,000 to 7.2/100,000 over a period of 19 years (Table 3 and Figure 3). There is no explanation for the fall among males but practically constant rate among females in this study (Table 3 and Figure 3).

The most common weapon used is a sharp object, as more than two fifths (43.4%) of the children who were killed were stabbed to death. About one third (31.56%) were killed by blunt force trauma (Table 4 and Figure 4). There is a custom in the Xhosa culture to give a boy a knife after the circumcision ceremony, when a child is circumcised and achieves adulthood through a knife. This was traditionally used for cutting pieces of meat in a gathering, but nowadays the children are using the knives for stabbing one another. Most of children undergo circumcision when they are younger than 18 years [19].

Blunt force trauma deaths of children is another matter of concern. Blunt objects are easily available, such as stones, bricks, iron rods, etc. The children are the unprotected victims of their alcoholic or drugaddicted fathers or guardians or any other adults, who often hit them over the head. Children whose paternity is disputed are commonly victims of such homicide. Sexual promiscuity has not only increased the risk of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections, but also the risk of illegitimate pregnancy [20]. These illegitimate children are often either the perpetrators or the victims of homicide. Only 33% of children in South Africa live with both parents [21]. Many of them are orphans, and these are the children at greater risk of being murdered. In a normal society these children would be either in school or at home with their mothers or other caregivers.

In this study, more than three-fifths (64.35%) of children who were killed were in the age group of 17 to 18 years old (Table 4 and Figure 5). It is understandable that older children of 16 and above are more prone to risk-taking behavior. A study carried out by Krug et al. (2002) showed increasing evidence that homicides contribute substantially to the burden of premature death among males between the ages of 15 and 24 years [22]. Children between 11 and 15 years are teenagers, and a sizeable percentage of 15.23% of them were also victims of homicide in this study (Table 4 and Figure 5). Young children are at greater risk of being killed as a result of child abuse than adolescents, who are most commonly killed during episodes of interpersonal violence [2]. The age group between 6 and 10 seemed to have more survival skills than the children of five or younger in this study (Table 4 and Figure 5). Again the reason is not known, but according to a study conducted in Dar-es- Salaam that reported a very high rate of early infanticide, it is possible that a high number of infants could be killed in this region as well [7]. Infants are more vulnerable to homicide than older children. A study conducted by Brown et al. (1995) showed that children in the first year of life are most vulnerable to becoming victims of homicide [23]. In 2000, there were 654 homicides of children younger than five years, representing an estimated 0.6% of all child deaths in that year in South Africa [24]. The findings in this study are contrary to those of the study carried out by Sherriff et al in 2015 in Mpumalanga province, where it was claimed that homicide occurs less often in rural regions than in urban areas in South Africa [9].

Excessive use of alcohol occurs among black Africans in this region. Alcohol and violence can be linked ritualistically as part of youth gang cultures [25]. Globally, across all age groups, alcohol is estimated to be responsible for 26% and 16% of years of life lost through homicide among males and females’ respectively [26]. Poor people indulge in alcohol or drug use to forget their sorrow. Low socio-economic conditions are an important cause of the high level of child homicide. The Transkei region is a third world region within South Africa where people are extremely poor [27]. When there is extreme poverty, children tend to be vulnerable just by virtue of experiences such as growing up without a father, poor parenting, family violence, neglect and abuse during childhood and living in poverty and in a context of social inequality are all pathways for violence [28].

Limitation

The population estimate has been obtained from the South African statistics department, but it is an approximation. It does not allow accurate calculation of the population in each police station’s area. A lot of migration takes place from this under-resourced region to wealthier regions of South Africa. However, population numbers could not have varied by more than 10% during the study period. The author was careful in collecting data but being a retrospective study, it has some limitation as data could be omitted during counting.

Ethical Issues

The author has ethical permission for collecting data and publication (approved project No. 4114/1999) from the Ethical Committee of the University of Transkei.

Conclusion

The average rate of child homicide was high in the Transkei region of South Africa. It is more than 12 times higher than in the world average, and also more than five times higher than in the rest of South Africa. Males were the victims of child homicide more than twice as often as females in this region of Transkei. About four-fifths of child homicides were recorded in the age group between 11 and 18 years, and about one-eighth of the children under the age of 10 were victims of homicide. The government will have to make concerted attempts to reduce the killing of children in the Transkei region of South Africa by improving socio-economic conditions and by educating the population.

Acknowledgment

The author would like to thank all staff members of the Forensic Pathology Laboratory for helping to collect data and providing information on police stations in this region. The author would also like to thank the South African statistics department at Mthatha for providing a population estimate of all the police stations.

References

- Abrahams N, Mathews S, Martin LJ, Lombard C, Nannan N, et al. (2016) Gender differences in homicide of neonates, infants, and children under 5 years in South Africa: Results from the Cross-sectional 2009 National Child Homicide Study. PLoS Med 13: e1002003.

- Viner RM, Coffey C, Mathers C, Bloem P, Costello A, et al. (2011) 50-years mortality trends in children and young people: a study of 50 low-income, and high-income countries. Lancet 377: 1162-1174.

- Nuno SA (2017) First ten countries with highest child homicide rates are in Latin America. NBC Universal.

- Finkelhor D, Ormrod R (2001) Homicides of Children and Youth. Juvenile Justice Bulletin.

- Matzopoulos R, Norman R, Bradshaw D (2004) The burden of injury in South Africa: Fatal injury trends and international comparisons. In: Suffla S, Van Niekerk A, Duncan N (editors). Crime, violence and injury prevention in South Africa: development and challenges. Tygerberg: MRC-UNISA Crime, Violence and Injury Lead Programme pp: 9-12.

- Prinsloo M, Laubscher R, Neethling I, Bradshaw D (2012) Fatal violence among children under 15 years in four cities of South Africa, 2001-2005. Int Inj Contr Saf Promot 19: 181-184.

- Outwater AH, Mgaya E, Campbell JC, Becker S, Kinabo L, et al. (2010) Homicide of Children in Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania. East Afr J Public Health 7: 345-349.

- Pinheiro P (2017) World report on violence against children. Geneva: United Nations.

- Sherriff B, Mackenzie S, Swart LA, Seedat MA, Bangdiwala SI, et al. (2007) A comparison of urban-rural injury mortality rates across two South African provinces. Int Inj Contr Saf Promot 22: 75-85.

- Save children (2012) Preventing child homicide after the recent death of a 5-year-old in Soweto.

- Gilbert R, Widom CS, Browne K, Fergusson D, Webb E, et al. (2009) Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. Lancet 373: 68-81.

- Matzopoulos R, Groenewald P, Abrahams N, Bradshaw D (2016) Where have all the guns gone? SAMJ 106: 589-591.

- Gun free South Africa (2015) Research shows South Africa’s gun law has saved lives, made country safer. GFSA.

- South African News (2017) Thirty million South Africans living in poverty. eNCA.

- Meel BL (2017) Incidence of unnatural deaths in Transkei sub-region of South Africa (1996-2015). S Afr Fam Pract 59: 138-142.

- Mathews S, Abrahams N, Jewkes R, Martin LJ, Lombard C (2013) The epidemiology of child homicides in South Africa. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 91: 562-568.

- Meel BL (2005) Community perception of traditional circumcision in a sub-region of the Transkei, Eastern Cape, South Africa. S Fam Pract 47: 58-59.

- Leclerc-Madlala S (2013) Why young women in Southern Africa are going for riskier older men. Exchange on HIV/AIDS Sexuality and Gender 4: 5-8.

- Ndebele B (2017) Only 33% of children in South Africa live with both parents. News24.

- Krug EG, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi AB, Lozano R (2002) World report on violence and health. World Health Organization.

- Browne K, Lynch M (1995) The nature and extent of child homicide and fatal abuse. Child Abuse Rev 4: 309-316.

- Bradshaw D, Bourne D, Nannan N (2003) What are the leading causes of death among South African children? MRC Policy Brief, No. 3, 2003 Tygerberg: Medical Research Council.

- Ohene S, Ireland M, Blum RW (2005) The clustering of risk behaviours among Caribbean youth. Maternal and Child Health Journal 9: 91-100.

- Abbey A, Zawacki T, Buck PO, Clinton M, McAuslan P (2001) Alcohol and sexual assault. Alcohol Research & Health 25: 43-51.

- Westaway A (2012) Rural poverty in Eastern Cape Province: Legacy of apartheid or consequence of contemporary segregationism? Development Southern Africa 29: 115-125.

- Mathew S, Jewkes R, Abrahams A (2011) ‘I had a hard life’: exploring childhood adversity in the shaping of masculinities among men who killed an intimate partner in South Africa. Br J Criminol 51: 960-977.

Citation: Meel B (2018) Incidence of Child Homicide in the Transkei Sub-Region of South Africa (1996-2014). Epidemiology (Sunnyvale) 8: 345. DOI: 10.4172/2161-1165.1000345

Copyright: © 2018 Meel B. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 5779

- [From(publication date): 0-2018 - Nov 25, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 4837

- PDF downloads: 942