Morphological Aspect of Oral Lichen Planus Lesions Depending on Infection with Hepatitis C Virus and Functional Hepatic Tests

Received: 11-May-2017 / Accepted Date: 07-Jun-2017 / Published Date: 09-Jun-2017 DOI: 10.4172/2161-0681.1000309

Abstract

Introduction: Due to its spread and implications, oral lichen planus has attracted particular attention from the medical world. Despite efforts, the etiology of oral lichen planus is currently incompletely understood. Establishing significant associations between oral lichen planus and hepatitis viruses helps to identify the population that requires screening for the markers of these viruses and implicitly, to diagnose these hepatitis cases.

Aims: To determine the frequency of association of oral lichen planus with HCV infection and to establish a correlation between the severity of hepatic involvement and that of lichen planus lesions.

Material and methods: Included 80 patients with oral lichen planus. All patients included in the study underwent biochemical liver function tests. Statistical analysis of clinical and para-clinical parameters was performed.

Results: The group of HCV-positive patients with oral lichen planus represented 42.5% of the study group. It was found that oral lichen planus with reticular lesions was the predominant clinical form. Regarding the relationship between the severity of oral lichen planus lesions and that of hepatic involvement, no correlation could be established between the degree of alteration of liver function tests and the severity of oral lesions. Thus, patients with high transaminase values had non-extensive lesions and mild, non-painful reticular forms, while other patients with normal or slightly changed liver function test values had extensive, particularly painful erosive lesions, with an altered general status.

Conclusions: There is no significant correlation between the degree of alteration of liver function tests and the severity of oral lesions. Oral erosive lesions had a significantly higher incidence in patients with at least one changed liver function test.

Keywords: Lichen planus lesion; Hepatitis C virus; Hepatic involvement; Correlation

315739Introduction

Due to its spread and implications, oral lichen planus has attracted particular attention from the medical world. Lichen planus is a chronic papulo-squamous disease with uncertain etiology and characteristic cutaneous and/or mucous manifestations [1]. Oral lichen planus lesions are characterized by polymorphism and dynamism, which often makes diagnosis difficult and raises differential diagnosis problems [1-12].

Despite efforts, the etiology of oral lichen planus is currently incompletely understood; a multitude of systemic and local factors are supposed to be involved in the development and maintenance of the disease: infection (mainly viral), metabolic disorders (diabetes mellitus), psychological factors (stress, depression, anxiety, etc.), hypertension, various chronic liver diseases, viral hepatitis B and C, etc. The last mentioned are severe diseases, with a wide distribution in the population. Of major interest is the association of oral lichen planus with viral hepatitis C [1,2,6,7,13-18]. Hepatitis C virus infection is considered to be a major public health problem worldwide, being responsible for 20% of acute hepatitis cases, 80% of chronic hepatitis cases, 40% of cirrhosis cases, 70% of hepatocellular carcinomas and 30% of liver transplantations. Globally, about 170 million persons, representing 3% of the world’s population, are infected with hepatitis C virus, and 3-4 million new cases are annually reported throughout the world [4-7]. On the other hand, the dentist can be the first medical practitioner who comes into contact with a patient infected with hepatitis C virus, due to oral lesions that are nothing else but extrahepatic manifestations of these infections. Establishing significant associations between oral lichen planus and hepatitis viruses helps to identify the population that requires screening for the markers of these viruses and implicitly, to diagnose these hepatitis cases.

Aims of the Study

• To determine the frequency of association of oral lichen planus with HCV infection.

• To establish a correlation between the severity of hepatic involvement and that of lichen planus lesions.

Materials and Methods

The study group was selected from patients who attended the Ambulatory Service of the Clinic of Odontology-Periodontology for a dental examination, or the Diagnosis and Treatment Center Cluj- Napoca for a dermatological examination and were subsequently referred to the above mentioned service, and included 80 patients with oral lichen planus (men and women). Diagnosis was made based on characteristic clinical manifestations, and in cases with uncertain diagnosis, histopathological examination was performed.

All patients with oral lichen planus underwent thorough history taking, and their demographic data (age at the time of examination, age at the time of presentation and at the disease onset, sex) were recorded, as well as the reasons for their presentation to the doctor, possible events linking patients to the development of lesions (use of certain oral hygiene or food products, drug treatments, stressful incidents, dental treatments for various dental restorations, etc.), personal pathological history (with emphasis on history of allergy and hepatitis C virus, patients with known allergies or chronic viral hepatitis C at the time of examination being recorded). The following were noted: the year of diagnosis of hepatitis, chronic alcohol consumption (more than 50 ml concentrated alcohol/day), the clinical and topographic form of lichen planus lesions, the degree of pain intensity, the extension and severity of lesions.

All patients included in the study underwent biopsy and biochemical liver function tests (ASAT, ALAT, alkaline phosphatase, bilirubin, γGT). HCV marker testing was carried out for 56 patients.

Biochemical liver function tests were performed in the serum, with an autoanalyzer (HITACHI 911), under standardized conditions, using kinetic methods. HCVAb were determined by the MONOLISA anti- HCV Plus immunoenzymatic reaction.

All patients were informed about the study and gave their consent for participation.

Statistical analysis of clinical and paraclinical parameters was performed: demographic data, psychological tests, hepatitis C and B virus markers, liver function tests, clinical lichen planus forms, lesion severity score, response to various treatments.

The statistical analysis was performed on groups of patients having more than 30 individuals. The student test was used for a comparison of independent samples. Pearson correlation factor was used for establishing a correlation between two numerical variables. For statistical processing of the results, SPSS 10.0, EPIINFO 2000 and Microsoft Office 2000 EXCEL software were used. The significance threshold for the tests employed was α=0.05.

Results

The total group of 80 cases (mean age 52.5 years) included 52 women (65%) and 28 men (35%), aged at the time of examination between 24-81 years, with a mean age of 51.61 years and 58 years, respectively. There was a predominance of the female sex, the female to male ratio being 52/28=1.86.

Of the group of 80 patients, 56 were tested for HCV markers and biopsies. The tests were reactive in 34 cases (60.71%) and negative in 22 cases (39.28%). In 23 of the 34 positive cases, positivity was detected starting from the dental examination.

For women, the age at the examination moment was between 24-81 years old, with an average of 52.04 years old. Men had 36-77 years old at the examination moment, with an average of 56.95 years old. When the OLP started the women had 24-81 years old with an average of 50.63, while the men had 36-70 years old with the average of 55.52 years old (Table 1).

| Age | Min | Max | Average | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age when the examination was performed | 24 | 81 | 54 | 1344 |

| Age when OLP began | 24 | 81 | 52 | 1288 |

Table 1: The age of patients at consultation and OLP time.

In the group of HCV-positive patients with oral lichen planus (34 patients, representing 42.5% of the study group), there were 21 women and 13 men. The proportion of women in the group was 61.77%, and that of men 38.24%; the involvement rate was 21/13=1.62 in favor of the female sex. The average age at the examination moment was 59.15 years old for men, 50.76 for women and 53.97 for the entire group.

In the group of HCV-negative patients with oral lichen planus (27.5%), there were 12 women (54.55%) and 10 men (45.46%). The involvement rate was 12/10=1.2 in favor of the female sex.

A predominance of the female sex in both groups was observed (without significant differences between the two groups). The average age at the examination moment was 58.20 years old for men, 55.08 for women and 56.50 for the entire group (Table 2).

| Sex | Age at examination moment | Age at the OLP beginning | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | Min | Max | Standard deviation | Median | Average | Min | Max | Standard deviation | Median | |

| Men | 57 | 36 | 77 | 12.02 | 60 | 56 | 36 | 70 | 13,59 | 60 |

| Women | 52 | 24 | 81 | 13.91 | 50.5 | 51 | 24 | 81 | 10,92 | 49 |

Table 2: The age of patients at examination and OLP time.

The comparison between the HCV positive and HCV negative groups show no statistical significant differences (p>0.05), therefore the virus having no influence over the age when the oral lesions appeared (Table 3).

| Age | HCV | Nr. of cases | Average age | p value | Standard deviation | Standard error |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at the examination moment | positive | 34 | 53,97 | NS | 13,31 | 2,28 |

| negative | 22 | 56,50 | 12,56 | 2,68 |

Table 3: Average age at the examination moment for the HCV positive and negative.

A demographic analysis, depending on HCV, of different groups of age showed no significant differences among groups (Table 4).

| Age | HCV | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | ||||||

| Feminine | Masculine | Total HCV+ | Feminine | Masculine | Total HCV- | ||

| 20-40 | 5 (100%) | - | 5 (71.4%) | 1 (50%) | 1 (50%) | 2 (28.6%) | 7 |

| 41-60 | 10 (66.7%) | 5 (33.3%) | 15 (62.5%) | 5 (55.6%) | 4 (44.4%) | 9 (37.5%) | 24 |

| 61-81 | 6 (42.9%) | 8 (57.1%) | 14 (56%) | 6 (54.6%) | 5 (45.4%) | 11 (44%) | 25 |

| Total | 21 (61.8%) | 13 (38.2%) | 34 (60.7%) | 12 (54.6%) | 10 (45.4%) | 22 (39.3%) | 56 |

Table 4: HCV prevalence detailed on different age groups.

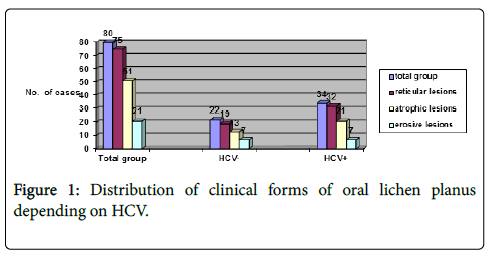

In the total group of patients included in the study (80 cases), the distribution of cases depending on the clinical form of oral lichen planus was the following Figures 1 and 2:

▪ reticular lesions 75 (93.75%)

▪ atrophic lesions 51 (63.75%)

▪ erosive lesions 21 (26.25%)

The group of 34 HCV+ patients with OLP had:

▪ reticular lesions 32 (94.11%)

▪ atrophic lesions 21 (61.76%)

▪ erosive lesions 7 (20.58%)

The group of 22 HCV- patients with OLP had:

▪ reticular lesions 19 (86.36%)

▪ atrophic lesions 13 (59.09%)

▪ erosive lesions 7 (31.81%)

It can be seen that oral lichen planus with reticular lesions was the predominant clinical form in all three groups.

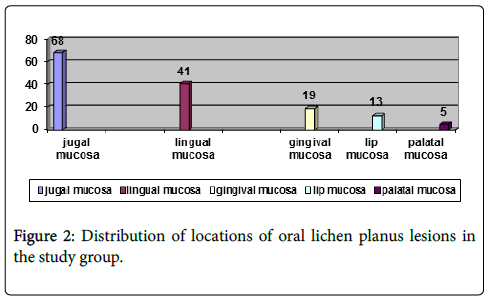

Clinical examination evidenced the following locations of oral lichen planus lesions:

▪ jugal mucosa: 68 cases (85%)

▪ lingual mucosa: 41 cases (51.25%)

▪ gingival mucosa: 19 cases (23.75%)

▪ lip mucosa: 13 cases (16.25%)

▪ palatal mucosa: 5 cases (6.25%)

Liver function tests

Liver function tests were performed in all studied patients (ASAT, ALAT, γGT, alkaline phosphatase, bilirubin). The total group of 80 patients included 29 (36.25%) cases with at least one changed liver test. In the group of 34 HCV-positive patients with lichen planus, the number of cases with at least one changed liver function test was 11 (32.35%), and in the group of 22 HCV-negative patients with lichen planus, this was 7 (31.81%). No statistically significant difference was observed between the two groups.

Based on history taking, the number of chronic alcohol users was established. Their proportion was 17.85% in the total group, 27.27% in the HCV-negative group compared to 11.76% in the HCV-positive group.

The clinical form of oral lichen planus

The patients included in the study had oral lesions (reticular 93.75%, atrophic 65%, and erosive 27.5%) and cutaneous lesions (37.5% of cases).

Among patients with liver function tests within normal limits (63.75% of the patients included in the study), 96.07% had reticular lesions (49 patients), while in the group of patients with at least one changed liver function test, reticular lesions were present in a proportion of 89.65% (26 patients). The incidence of atrophic lesions was similar in the two groups: 64.7% (33 patients) and 65.51% (19 patients), respectively. However, great differences in the incidence of erosive lichen planus lesions were found, incidence being 55.17% (16 patients) in patients with at least one changed liver function test and 11.76% (6 patients) in those with liver function tests within normal limits.

No correlation could be established between the degree of alteration of liver function tests and the severity of oral lesions, patients with high transaminase values having non-extensive lesions and mild reticular clinical forms, while other patients with normal or slightly altered liver function test values had severe erosive lesions.

Discussions

The proportion of HCV positivity found in this study (42.5%) is in the range of high values reported by the literature [1-7]. This figure is significant through both the great number of patients included in the study and the relatively high number of cases for which HCV testing was performed.

An important aspect is the high number of patients in whom the presence of HCV was detected starting from the presence of lichen planus lesions, i.e., 23 of the tested subjects. Those patients were not known to have chronic hepatitis and had no symptoms suggesting liver disease. This aspect is significant, emphasizing the role of the dentist in detecting a severe gastrointestinal disease-viral hepatitis C [4,7].

In the presence of oral lichen planus, liver function tests and HCV marker testing are recommended. Also, it is recommended to monitor patients and repeat the tests in case of non-reactive markers, given that between the infecting time and the development of anti-HCV antibody positivity there is a long time period of 10 up to 16 weeks.

The statistical comparison of the frequency of cases with altered liver tests between the HCV-positive group, the HCV-negative group and the total group of patients with lichen planus showed no statistically significant differences between them which is in agreement with other studies [1-7]. Also, the frequency of cases with changed liver function tests in the group of HCV-positive patients with lichen planus was only 32.35%. These aspects show the fact that liver function tests cannot be a sufficient guiding criterion for the selection of cases that require HCV marker testing. Oral lichen planus can be associated with other liver diseases [1-7]. We also mention the high degree of association of changed liver function tests with chronic alcohol consumption in HCV-negative patients with oral lichen planus (27.27%).

Regarding the relationship between the severity of oral lichen planus lesions and that of hepatic involvement, no correlation could be established between the degree of alteration of liver function tests and the severity of oral lesions similar with other studies [4-7]. Thus, patients with high transaminase values had non-extensive lesions and mild, non-painful reticular forms, while other patients with normal or slightly changed liver function test values had extensive, particularly painful erosive lesions, with an altered general status [6,7].

In this study, we observed a significantly higher incidence of erosive lesions (55.17%) in patients with at least one changed liver function test compared to patients with tests within normal limits (11.74%). Our findings are in agreement with De Carli's [4] and Tovaru's [7] findings.

Conclusions

Lichen planus has a multi-factorial etiology, which is also correlated with hepatitis C virus infection.

The alteration of liver function tests cannot be the only criterion for patient selection regarding the need to assess hepatitis C virus markers.

It is indicated to determine hepatitis C virus markers in all patients with lichen planus.

Between the infecting time and the development of viral hepatitis marker positivity there is a long time period (10-16 weeks), which requires further follow-up of cases in which markers were not reactive, by repeating the tests.

There is no significant correlation between the degree of alteration of liver function tests and the severity of oral lesions.

Oral erosive lesions had a significantly higher incidence in patients with at least one changed liver function test.

References

- Vanzela TN, Almeida IP, Bueno Filho R, Roselino AM (2017) Mucosal erosive lichen planus is associated with hepatitis C virus: analysis of 104 patients with lichen planus in two decades. Int J Dermatol 56: e143-e144.

- Yoshikawa A, Terashita K, Morikawa K, Matsuda S, Yamamura T, et al. (2017) Interferon-free therapy with sofosbuvir plus ribavirin for successful treatment of genotype 2 hepatitis C virus with lichen planus: a case report. Clin J Gastroenterol 10: 270-273.

- Nagao Y, Kimura K, Kawahigashi Y, Sata M (2016) Successful Treatment of Hepatitis C Virus-associated Oral Lichen Planus by Interferon-free Therapy with Direct-acting Antivirals. Clin Transl Gastroenterol 7: e179.

- De Carli JP, Linden MS, da Silva SO, Trentin MS, Matos Fde S, et al. (2016) Hepatitis C and Oral Lichen Planus: Evaluation of their Correlation and Risk Factors in a Longitudinal Clinical Study. J Contemp Dent Pract 17: 27-31.

- Gheorghe C, Mihai L, Parlatescu I, Tovaru S (2014) Association of oral lichen planus with chronic C hepatitis. Review of the data in literature. Maedica (Buchar) 9: 98-103.

- Barbosa NG, Silveira ÉJ, Lima EN, Oliveira PT, Soares MS, et al. (2015) Factors associated with clinical characteristics and symptoms in a case series of oral lichen planus. Int J Dermatol 54: e1-6.

- Tovaru S, Parlatescu I, Gheorghe C, Tovaru M, Costache M, et al. (2013) Oral lichen planus: a retrospective study of 633 patients from Bucharest, Romania. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 8: e201-e206.

- Maier N, Maier C, Folescu F (1999) Dermatologie-Venerologie şi patologia mucoasei bucale. Arad: “Vasile Goldiş†University Press. 179-182.

- Setterfield JF, Black MM, Challacombe SJ (2000) The management of oral lichen planus. Clin Exp Dermatol 25: 176-182.

- Pambuccian Gr (1987) Morfopatologie stomatologică. Bucureşti, Editura Medicală 215-221.

- Pop A (1997) Patologia mucoasei orale. Partea I. Cluj-Napoca: Editura Dacia pp: 98-102.

- Protocol clinic naÅ£ional “Hepatita virală C acută la adultâ€(2008) ChiÅŸinău. Rep Moldova.

- Greenberg MS (2002) Ulcerative, vesicular, and bullous lesions. In: Greenberg MS, Glick M, editors. Burket’s Oral Medicine Hamilton Ontario, USA. pp: 51-84.

- Gimez-Garcia R, Pérez-Castrillón JL (2003) Lichen planus and hepatitis C virus infection. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venerol 17: 291-298.

- Nagao Y, Sats M, Abe K, Tanikawa K, Tameyama T (1997) Immunological evaluation in oral lichen planus with chronic hepatitis C. J Gastroenterol 32: 324-329.

- Brunk D (2002) Watch for the skin signs of hepatitis C infection. Skin and Allergy News 33: 22.

- Rebora A (2002) Erosive lichen planus: what is this? Dermatology 205: 226-228.

- Nagao Y, Sata M, Ide T, Suzuki H, Tanikawa K, et al. (1996) Development and exacerbation of oral lichen planus during and after interferon therapy for hepatitis C. Eur J Clin Invest 26: 1171-1174.

Citation: Rotaru DI, Moga RA, Avram R (2017) Morphological Aspect of Oral Lichen Planus Lesions Depending on Infection with Hepatitis C Virus and Functional Hepatic Tests. J Clin Exp Pathol 7:309. DOI: 10.4172/2161-0681.1000309

Copyright: © 2017 Rotaru DI, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 4348

- [From(publication date): 0-2017 - Aug 19, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 3422

- PDF downloads: 926