Newly Prescribed Atypical Antipsychotics in the Hospitalized Elderly and their Continuation on Discharge

Received: 17-Aug-2018 / Accepted Date: 12-Sep-2018 / Published Date: 22-Sep-2018

Keywords: Atypical antipsychotics; Elderly; Discharge communication; Inappropriate medication use; Polypharmacy; Hospital pharmacy

Introduction

Use of a medication is deemed “off-label” when it is used outside of an approved dose, time frame, population or indication as dictated by the product monograph [1]. In Canada, atypical antipsychotics are indicated for treating psychoses in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, and as adjunctive therapy for major depressive disorder [2]. Atypical antipsychotics are also used off-label to control symptoms of delirium, such as agitation [3]. Approximately 8%-17% of elderly patients presenting to the emergency department are diagnosed with delirium [4]. Delirium symptoms should dissipate as the underlying cause resolves and duration of treatment with atypical antipsychotics should be determined by the persistence of harmful symptoms. The use of atypical antipsychotics should be re-evaluated regularly [3,5]. The elderly are particularly vulnerable to adverse drug reactions which often can result in hospital readmission [6]. In a study by Scales et al, older patients and those with longer hospital stays had higher rates of continuation of temporary medications at hospital discharge, including antipsychotics [7-10]. The safety of atypical antipsychotic agents in particular has been of concern since the discovery of a 1.7-fold increase in the relative risk of death when used in elderly patients with dementia in trials with as little as 10 weeks duration [11]. This prompted advisories and warnings for atypical antipsychotics, both in the US and in Canada in 2005 [11]. Furthermore, the use of any antipsychotic, typical or atypical to prevent or treat delirium has not been shown to alter either the duration or severity of delirium symptoms [12]. Data is lacking regarding the proportion of elderly patients who are started on atypical antipsychotics in hospital and subsequently prescribed them on discharge. Our study aimed to determine the proportion of 5 elderly patients newly prescribed an atypical antipsychotic in hospital that is continued after discharge, to describe the presence or absence of a documented follow-up plan in regards to these new agents, and the indications for use of atypical antipsychotics in hospital.

Methods

This retrospective, observational study used electronic patient records stored in the Open Clinical Information System database at our institution. Prior to conducting this study, approval from our institution’s Research Ethics Board was obtained.

Inpatient atypical antipsychotic prescriptions were identified using AHFS code 28:16:08, which includes use of any of the following agents documented on the patient’s electronic pharmacy profile: aripiprazole, asenapine, lurasidone, clozapine, risperidone, paliperidone, quetiapine, ziprasidone or olanzapine.

Patients 65 years and older admitted to an internal or family medicine service within our institution between November 2014 to November 2015 who were newly prescribed an atypical antipsychotic while in hospital were eligible for inclusion. This age group was chosen to identify an elderly population, commonly represented in research as 65 years of age and above [10]. Eligible patients were identified using data generated by our institution’s health records department (Health Records).

One hundred patients were selected randomly, using a column of random numbers generated in Excel, from the list of 1184 potentially eligible patients provided by Health Records. A single investigator (AF) screened patients for eligibility by applying the exclusion criteria sequentially as follows, until 100 patients meeting inclusion criteria were identified: (1) a documented antipsychotic on their best possible medication history 6 (BPMH) indicating a prescription for an antipsychotic prior to admission, (2) death in hospital, or (3) a discharge date outside of the study period.

All data was extracted by a single investigator (AF) into an Excel spreadsheet. Electronic discharge medication reconciliation documents were reviewed to determine whether an atypical antipsychotic was prescribed on discharge. For those prescribed an atypical antipsychotic on discharge, the discharge medication reconciliation and discharge summary documents were reviewed to determine whether a followup plan for the atypical antipsychotic prescription was documented. A documented follow-up plan was required to include instructions for a specified health care professional to monitor or adjust this new medication, documentation that the patient would be followed as an outpatient by an appropriate consult team such as the outpatient geriatric service, or any specific instructions related to the newly prescribed atypical antipsychotic. A comment that the patient should follow-up with their primary care provider within an appropriate amount of time without giving instructions related to this newly prescribed atypical antipsychotic did not qualify as a documented follow-up plan.

Demographic data including birth year/month, sex, admission diagnosis, past medical history, medications prescribed prior to admission and on discharge were also collected.

The indication for initiation of the atypical antipsychotic was determined by reviewing the electronic discharge note, medication administration records, and inpatient progress notes from one day prior to and two days after the initial prescribed date of the atypical antipsychotic. Electronic records were reviewed for presence of consultations to specialty services during the admission, specifically psychiatry, geriatric psychiatry, the geriatric psychiatry behavioural support team or geriatrics [7].

Results

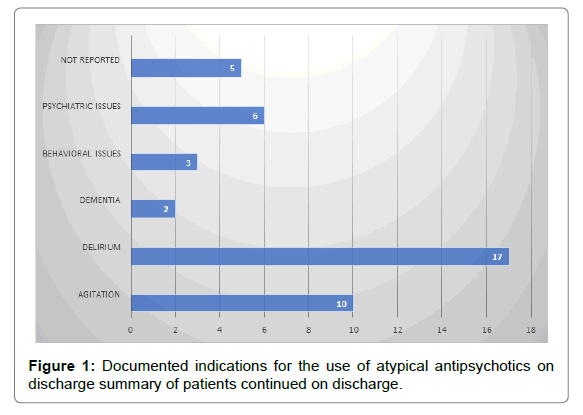

The proportion of patients that received a prescription for an atypical antipsychotic on discharge was 43% (95% confidence interval, 33% to 53%). Of those patients prescribed atypical antipsychotics on discharge, 56% had no documented follow-up plan for monitoring or reassessing this medication. The most common indications noted on the discharge summary for atypical antipsychotics prescribed on discharge were delirium/confusion (40%) and agitation/aggression (23%). For the five patients with no indication noted on the discharge summary, indications noted in additional documentation included agitation (n=3), sleep disturbances (n=1) and anxiety (n=1).

Risperidone, quetiapine and olanzapine represented 51%, 37% and 12%, respectively, of atypical antipsychotic prescriptions at discharge of patients continued on an atypical antipsychotic at discharge, 51% had a consult with the geriatric psychiatry behavioural support team during their admission, as compared to 37% of those patients who were not prescribed an atypical antipsychotic at discharge. A geriatrics service other than the geriatric psychiatry behavioural support team was consulted 17 times in the group continued on an atypical antipsychotic at discharge versus 14 times in those who did not continue at discharge.

The largest proportion of patients, both those continued on an atypical antipsychotic at discharge and those who were not, were discharged from the alternate care medicine service (44% and 35% respectively). This service admits stable patients waiting for long-term care or an organization of increased home care resources.

Discussion

Our study demonstrated that a large proportion of patients who were newly prescribed atypical antipsychotics in hospital were prescribed these medications on discharge. Despite the lack of previous evidence in this patient population, it was hypothesized through clinical experience and observation that a significant proportion of elderly patients would be discharged from hospital with continued prescriptions for newly prescribed atypical antipsychotics. Published literature in a different patient population also supports this hypothesis. In a study by Karalea et al. evaluating the continued use of atypical antipsychotics prescribed for ICU patients experiencing delirium, it was found that 47% of patients continued to receive these agents after discharge from ICU and of these patients, 71.4% continued their atypical antipsychotic medications on discharge from hospital. Our study showed that 43% of elderly patients started on an atypical antipsychotic in hospital were continued on this agent at discharge, consistent with the results seen in patients being discharged from the ICU in the study by Karalea et al.

The majority of atypical antipsychotics in our study were newly prescribed for inpatients to manage symptoms of delirium. The duration of delirium symptoms can vary between patients and should dissipate as the underlying cause resolves, however, symptoms can persist for many weeks [5]. Many of the patients in our study may have had ongoing, though diminished symptoms of delirium at the time of discharge, for which their physicians deemed it appropriate to continue the atypical antipsychotic that had been effective to manage these symptoms in hospital. This could help to explain why a large proportion of these patients were continued on this medication at discharge.

Our study found that risperidone, quetiapine and olanzapine, respectively, were the atypical antipsychotics most frequently continued on discharge from hospital at our institution. Low doses of atypical antipsychotics are commonly used off-label for agitation, anxiety and insomnia [1]. In a study evaluating prescription claims 9 through Veterans Affairs, quetiapine had the largest proportion of off-label use (42.9%), followed by risperidone (21.2%) and olanzapine (7.5%) [9]. The same three atypical antipsychotics stood out in a Canadian study describing the increase in filled prescriptions for antipsychotics. Between 2005 and 2012 the number of quetiapine prescriptions increased by 300%, while prescriptions for both risperidone and olanzapine increased 37.1% [5]. Based on this data, it could be expected that quetiapine would have been the most frequently continued atypical antipsychotic, when in fact risperidone was. This could be explained by local prescribing preferences of geriatric specialists at our institution where low doses of risperidone are preferred over the use of quetiapine.

In our study, consults to the geriatric behavioral support team were more common in the group of patients continuing on atypical antipsychotics after discharge at 51% compared to 37% of those not continuing on these medications at discharge. This could indicate the presence of more complex issues including ongoing symptoms of delirium requiring treatment with atypical antipsychotics in this group of patients.

Of the patients continued on atypical antipsychotics at discharge in our study, the majority did not have a documented follow-up plan regarding these medications included in their discharge summary. This is consistent with published information showing that discharge summaries are often lacking important information in regards to medication changes, expected duration of therapy and indications for newly prescribed medications. A study evaluating the content of discharge summaries showed that critical information such as discharge medications and specific follow-up plans is often missing (Figure 1) [11].

The discharge summary is a vital tool of communication between the hospital physician and the primary care provider in the community, and therefore should contain all necessary information the primary care physician requires to continue caring for the patient. It has been demonstrated that discharge summaries are often 10 received by the primary care provider many days after discharge or in some cases never arrive. When discharge summaries are received it is imperative that they contain pertinent information including the rationale for starting or changing medications, as well as follow-up instructions for the patient and family physician [11]. The community pharmacist is also impacted by the lack of documentation on discharge. Ensuring that the pharmacist is also aware of the rationale for use and intended duration of any new medication on discharge can enable them to determine the most appropriate and effective dose for each patient. The issue remains that a vast majority of the patients in our study who continued on an atypical antipsychotic at discharge did not have a clearly documented plan for an outpatient physician to follow-up with regards to this new medication. Though patients may have valid indications for continuing an atypical antipsychotic after discharge, this medication should be evaluated regularly. If follow-up was not documented on discharge, there is a possibility that these medications could be continued indefinitely (Table 1).

| Characteristics | Patients prescribed an atypical antipsychotic on discharge (n=43) | Patients not prescribed an atypical antipsychotic on discharge (n=57) |

|---|---|---|

| Females (n (%)) | 29 (67%) | 28 (49%) |

| Mean Age (yrs) | 76 | 75 |

| Age 85 years of age and older (n (%)) | 19 (44%) | 24 (42%) |

| Number of consults sent to Geriatric Psychiatry Behavioural Support team (n(%)) | 22 (51%) | 21 (37%) |

| Known history of dementia (any type) unspecified, mixed, vascular, etc. | 16 (37%) | 24 (42%) |

Table 1: Baseline characteristics.

This study has many limitations owing to its reliance on data documented in the patient health record. Follow-up plans for atypical antipsychotic prescriptions may have been communicated to other healthcare providers by means other than the discharge summary. However in observing the usual practice of the medical team, this does not seem to occur often. The online pharmacy records stored on our electronic Health record were used to determine medication use, however it is possible patients prescribed an atypical antipsychotic may not have actually received a dose. Records on O differ from a patient’s medication administration record in that it is compiled from physicians’ orders, not from the record of administration by nursing staff. We deemed this limitation was justified due to the consideration that an atypical antipsychotic included on a patient’s discharge medication reconciliation would increase the chance of receiving it as an outpatient regardless of whether it was administered as an inpatient. If patients receive an atypical antipsychotic as an outpatient that they were not actually administered in hospital, they could be at a higher risk of adverse events than those who continue receiving regular doses. Additionally, indications for use could be inaccurate, as they were [11].

Inferred from the patient health record by a single investigator. For example, if delirium was noted as a diagnosis that presented during hospital stay on the discharge summary, this was presumed to be the indication for the atypical antipsychotic; an explicit statement regarding indication for an atypical antipsychotic was not often noted on the discharge summary.

Conclusion

Despite the known risks, a large proportion of elderly patients newly started on atypical antipsychotics in hospital are being discharged with a prescription for these medications. Indications for prescribed atypical antipsychotics varied, with delirium and agitation being the most common. A follow-up plan for atypical antipsychotic prescriptions was often not documented on the discharge summary. Our study highlights the need for better written communication by healthcare providers at the time of discharge from hospital to ensure that continued use is justified, given the associated risks.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the hospital Research team at the Winchester District Memorial District Hospital for critically reviewing our study protocol.

References

- McKean A, Monasterio E (2012) Off-label use of atypical antipsychotics, cause for concern? CNS Drugs 26: 383-390.

- Heather M (2015) Psychosis. Jovaisas B (ed) Therapeutics Ottawa: Canadian Pharmacists Association.

- Skakum K, Reiss, JP (2015) Acute agitation. In: Jovaisas, Barbara (ed) Therapeutics Ottawa: Canadian Pharmacists Association.

- Inouye SK, Westendorp RGJ, Saczynski JS (2014) Delirium in elderly people. Lancet 383: 911-922.

- Adamis D, Trloar A, Martin FC, MacDonald AJD (2006) Recovery and outcome of delirium in elderly medical inaptients. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 43: 289-298.

- Proulx J (2014) Adverse drug reaction-related hospitalizations among seniors, 2006 to 2011. CIHI 17: A16.

- Scales DC, Fischer HD, Li P, Bierman AS, Fernandes O, et al. (2015) Unintentional continuation of medications intended for acute illness after hospital discharge: A population-based cohort study. J Gen Intern Med 31: 196-202.

- Singh S (2005) Increased mortality among elderly patients with dementia using atypical antipsychotics. CMAJ 173: 252.

- Neufeld KJ, Yue J, Robinson TN, Inouye SK, Needham DM (2016) Antipsychotic medication for prevention and treatment of delirium in hospitalized adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 64: 705-714.

- Sabharwal S, Wilson H, Reilly P, Gupte CM (2015) Heterogeneity of the definition of elderly age in current orthopaedic research. SpringerPlus.

- Kamble P, Sherer J, Chen H, Aparasu R (2010) Off-label use of second-generation antipsychotic agents among elderly nursing home residents. Psychiatric Services 61: 130-136.

- Leslie DL, Mohamed S, Rosenheck RA (2009) Off-label use of antipsychotic medications in the department of veterans affairs health care system. Psychiatric Services 60: 1175-1181.

Citation: Elbeddini A (2018) Newly Prescribed Atypical Antipsychotics in the Hospitalized Elderly and their Continuation on Discharge. J Dement 2: 106.

Copyright: © 2018 Elbeddini A. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Usage

- Total views: 3492

- [From(publication date): 0-2018 - Oct 09, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 2612

- PDF downloads: 880