Research Article Open Access

Return to Sports and Functional Outcome after Primary Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction in Jamaica

Wayne Palmer1, Ayana Crichlow1 and Akshai Mansingh2*

1Division of Orthopaedics, Department of Surgery, Radiology, Anaesthesia and Intensive Care, The University of the West Indies Mona, Kingston, Jamaica

2Division of Sports Medicine, Faculty of Medical Sciences, The University of the West Indies, Kingston, Jamaica

- *Corresponding Author:

- Mansingh A

Division of Sports Medicine

Faculty of Medical Sciences

The University of the West Indies

Kingston 7, Jamaica, USA

Tel: 1-876-977-6714

Fax: 1-876-977-2289, 1876-977-3470

E-mail: akshai.mansingh@uwimona.edu.jm

Received Date: January 19, 2016; Accepted Date: April 29, 2016; Published Date: May 09, 2016

Citation: Palmer W, Crichlow A, Mansingh A (2016) Return to Sports and Functional Outcome after Primary Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction in Jamaica. Sports Nutr Ther 1: 109. doi: 10.4172/2473-6449.1000109

Copyright: © 2016 Palmer W, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Nutrition Science Research

Abstract

Objective: The aim of this study was to assess the function and number of patients who returned to sports after undergoing primary anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Methods: The study consisted of two arms, a retrospective and a prospective arm. For the retrospective arm, the medical records of patients who underwent primary anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction between January 1, 2005 and December 31, 2010 were reviewed. For the prospective arm: patients seen between January 1st, 2011 and December 31st, 2011 were reviewed. The subjects were then contacted and evaluated by the Tegner-Lysholm Score, the International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) score, clinical knee examination and KT-1000 arthrometer. The patient’s ability to return to sports was documented. The data was analyzed using EXCEL 2008 and SPSS version 20 for Mac. Results: Seventy three (73) patients were identified, of which 46 were included in the study. Thirty two (32) patients participated in competitive sports. Majority of the patients were males (32/46), average age was 27 years (range 16 -51) at the time of surgery. All patients underwent single bundle arthroscopic-assisted anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with ipsilateral patella bone-tendon bone autograft. After surgery 36 (78%) patients returned to sports. The majority of patients had good knee-impairment function. Patients took approximately 9 months (range 2-19) to return to sports. 24 (66%) patients returned to their pre-injury level and 12 (34%) patients returned to a lower level. Ten (10) patients did not return to sports. Fear of re-injury was the most common reason. Conclusion: Despite good short and long-term knee outcome scores, athletes were still fearful of re-injury and this prevented them from returning to their previous level of sports.

Keywords

Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction; Knee; Return to sports; Pre-injury level; Jamaica

Introduction

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is a key knee stabilizer and its main function is to prevent anterior translation of the tibia on the femur [1]. It is one of the more commonly damaged knee ligaments and this occurs mainly while playing pivoting sports such as netball, soccer and hockey.

The anterior cruciate-deficient knee in many patients prevents successful return to sports and their best chance of doing so is by undergoing primary anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. There is also a higher incidence of secondary knee injury to the meniscus if athletes with an anterior cruciate-deficient knee return to sports [2].

Literature review.

ACL injuries remain high in the athletic arena. Orthopaedic Sports Medicine has identified it as the single largest problem affecting our athletes [1]. The true incidence for persons with an ACL injury is not known as some persons who have this diagnosis learn to cope and adjust their daily activities of living and never come to medical attention and others who are diagnosed are undocumented in the literature [3]. However it is estimated that an ACL tear is seen in 1 in every 3500 persons in the general population in U.S.A, approximately 175 000 to 200 000 undergo ACL reconstructions annually [4,5]. The rate of return to sports participation after reconstruction is diminished in elite athletes and sport-specific performance may deteriorate [6-9].

A study conducted by the National Football League during a 4 year period (1994-1998) indicates that an averaging 2100 injuries were reported per year with knee injuries accounting for 20% of all injuries of which 2% were ACL injuries [10]. ACL injury is a non-contact event which occurs more frequent in females than male athletes [11-14]. Female athletes have a rate of two to eight times greater than males which is due to increased knee abduction, generalized joint laxity, smaller ACL size, and hormonal effects of oestrogen on ACL [3,7-9].

Information from the Scandanavian ACL registries shows annual incidences of primary ACL reconstructions in Norway of 34 per 100,000 inhabitants, while in Denmark the incidence was 38 per 100,000 and in Sweden 32 per 100,000 persons in their general population between 2004 and 2007 [15].

The most common arthroscopic finding is ACL injuries, where hemarthrosis was significantly associated with ACL and meniscal tears. When compare sports to recreational injuries, the number of ACL injuries is greater during sports activities [15].

The incidence of ACL injuries in sports is significantly higher during competition than training and this finding is consistent among all sports [16]. Athletes and active individuals are more knowledgeable about ACL injury when compared to the general population [17].

This study was done to assess the number of patients who returned to sports after undergoing primary anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and review their knee function at the University Hospital of the West Indies, Jamaica.

Patients and Methods

Ethical approval was obtained from the University Hospital of the West Indies/The University of the West Indies/ Faculty of Medical Sciences Ethics Committee. Informed consent was obtained from all patients (or had parenteral consent if less than 18 years) prior to participation in the study.

The study consisted of two arms, a retrospective and a prospective arm. Inclusion criteria for both arms included patients who were >16 years old and had sustained an ACL tear requiring primary ACL reconstruction (Retrospective arm: patients seen between January 1st, 2005 and December 31st, 2010; Prospective arm: patients seen between January 1st, 2011 and December 31st, 2011). Patients who had revision ACL surgery or multi-ligament knee injury were excluded. Patients in the prospective arm were examined pre-operatively and reviewed during the following year, at two weeks, six weeks, three, six and twelve months after surgery. All patients received the same rehabilitation protocol and were subjected to the outcomes scores at the time of clinical evaluation.

Information regarding demographics and specific questions regarding knee function and its effect on activity during sports and daily chores was collected. Knee subjective outcome scores used included the Tegner-Lysholm Score and the subjective portion of the revised 2000 International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) score. Clinical knee evaluation was done using the objective IKDC score and the KT- 1000 arthrometer and both knees were examined and compared by a single orthopaedic surgeon who has extensive experience in conducting the testing procedure with the KT-1000 arthrometer.

All patients underwent single bundle arthroscopic-assisted primary anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with ipsilateral patella bonetendon bone autograft. Forty-four patients had tibial interference screw fixation and two had tibial staple fixation. All patients had femoral interference screw fixation. Fifteen patients had associated injuries that required surgical intervention at the time of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and this included twelve meniscal and three osteochondral procedures.

Outcome measures

Tegner activity rating scale: The Tegner activity rating scale assessed the patient’s participation level in sports and is applied before and after surgery to assess if the patient has returned to the same preinjury activity level. In this scale a score of more than 5 was required for participation in this study as this indicated that the patient at least partake in a recreational sport twice a week.

Tegner-Lysholm score: The Tegner-Lysholm Score is a subjective rating scale, which assessed the patient’s activity level before and after surgery. It comprises of eight knee symptoms of which each symptom has a range of function which the patient matches to their level of activity if the symptom occurred. The total score is graded as poor (< 66), fair (66-83), good (84-90) and excellent (> 90).

Revised 2000 International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) score: The revised 2000 International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) score consists of subjective and objective portions. The subjective IKDC score ascertained knee function during daily chores and sports [18]. A score of 100 means that there are no limitations with activities and an asymptomatic knee. The objective IKDC score looks at the worst grade (out of 4) among range of motion, effusion and knee laxity. The subjective and objective IKDC scores are assessed separately and never totaled.

KT-1000 arthrometer: The KT-1000 arthrometer assesses the sideto- side difference in anterior tibial translation between the injured and the uninjured knee at an applied force of 134N and 30 degrees of knee flexion. A difference of 1-3 mm implies that knee stability has been restored after surgery to the injured knee.

The patient’s ability to return to a sport as well as the type of sport(s) played was documented. A sport was defined as all forms of physical activity which, through participation, aim at expressing or improving physical fitness and mental well-being, forming social relationships or obtaining results in competition at all levels [19]. In those persons who failed to return to sports the reasons for no further involvement were reviewed. The level of participation in sports before injury and after surgery was classified as non-sporting, recreational and competitor (local, regional or national elite level). For patients who participated in more than one sport their highest participation level was used and the sport played at this level was recorded. The patient’s return to sports at the same or a lower level of participation before injury and after surgery was analyzed using the above classification and the Tegner Activity Scale. In the patients who were apart of the retrospective arm of the study, the level of participation before surgery, after surgery and at the time of review was compared.

In the prospective arm of the study patients were advised to return to sports after having adequate hamstring and quadriceps strength, knee range of motion, stability and function as compared to the opposite unaffected knee and after successfully undergoing a phase of sportsspecific training (Table 1). Knee stability was clinically assessed using the objective IKDC evaluation components of knee laxity (anterior drawer, Lachman and pivot shift tests), one-leg hop functional test and KT-1000 arthrometer.

| Time to return to sports | 4-6 months |

|---|---|

| Strength | Quadriceps and hamstrings ³90% of normal |

| ROM | Full extension and flexion |

| Function | Complete several functional drill tests (run, jog, move laterally and backwards) |

| Brace | Optional |

Table 1: Patient's criteria for return to sports.

Data Analysis

The data was statistically analyzed using EXCEL 2008 and SPSS version 20 for Mac. Bivariate tests such as paired t-test or chi-square test were used or where necessary the alternate nonparametric tests were employed for analysis.

Results

Seventy three (73) patients underwent primary ACL reconstruction between 2005 and 2011 of which 46 met the inclusion criteria and gave consent. Prior to injury the majority of patients (n = 32), participated in competitive sports and irrespective of their level of participation the most common sports that patients participated in were netball and football .Thirty-two patients were men and the average age was 27.3 years (range 16-51) at the time of surgery.

All patients underwent single bundle arthroscopic-assisted primary ACL reconstruction with ipsilateral patella bone-tendon bone autograft. Forty-four patients had tibial interference screw fixation and two had tibial staple fixation. All patients had femoral interference screw fixation. Fifteen patients had associated injuries that required surgical intervention at the time of ACL reconstruction and this included twelve meniscal and three osteochondral procedures. Of note, two patients underwent two procedures along with primary ACL reconstruction.

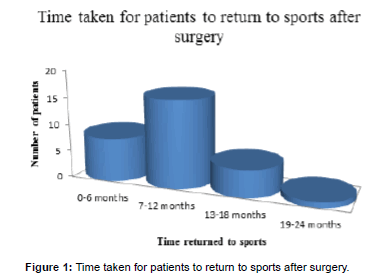

After surgery 36 (78%) patients returned to sports at an average of 9 months (range 2-19). Six persons could not accurately remember when they returned to sports (Figure 1).

Twenty four (66%) patients returned to their pre-injury level (15 competitive and 9 recreational) and 12 (34%) patients returned to a lower level of pre-injury participation. Of the 32 patients who played competitive sports prior to surgery, 15 (47%) returned to this level of participation, which included sports at the local, regional or national stage (Figure 1). Using the Tegner activity level scale, however, only 16 (44%) patients returned to their pre-injury participation level. Ten patients did not return to sports after surgery. Fear of re-injury was the most common reason given. Two patients had medical reasons for not playing sports again, which included postoperative knee instability and foot drop from a common peroneal nerve injury.

On analyzing eight patients with four to six year follow up, seven returned to sports; six to the same pre-injury level of participation (five recreational and one competitive).

In the prospective arm, one year after surgery 69.2% patients had good to excellent Tegner-Lysholm scores as compared to 7.6% good to excellent scores preoperatively. The median subjective IKDC scores improved from 40.2 (range 24.1-77) pre-operatively to 81(range 37-94) one year after surgery. Also, the objective IKDC scores preoperatively were 25% normal or near normal knee function and postoperatively improved to 100% normal or near normal knee function.

Only seven of the 14 prospective patients were evaluated with the KT-1000 machine one year after surgery. All had differences within 1-3 mm of tibial translation when compared to the opposite normal knee.

The knee impairment function scores for patients who returned to sports and those who did not return to sports one year after surgery were compared (Table 2). There were lower Tegner –Lysholm and Subjective IKDC scores noted in the patients who did not return to sports but this was not statistically significant (p > 0.05).

| Outcome measures | Returned to sports | Did not return to sports |

|---|---|---|

| Tegner-Lysholm Score | 89%, good to excellent 11%, fair to poor | 25%, good to excellent 75%, fair to poor |

| Mean 83.8 ± 7 | Mean 60±22.8 | |

| Objective IKDC | 100%, Normal and nearly normal | 100%, normal |

Table 2: Knee function outcome scores in patients who returned and did not return to sports.

Of the eight patients with the long follow up (four to six years), knee-impairment function score, seven good to excellent Tegner- Lysholm scores and the median subjective IKDC score was 91.4. All eight had normal or nearly normal knee objective IKDC function (Table 3). Of note, these results were as good as the outcome scores noted in the patients who were examined one year after surgery.

| Outcome measure | Result |

|---|---|

| Tegner-Lysholm Score | 87.5%,good to excellent 12.5%,poor to fair |

| Subjective IKDC | Median 91.4 (range 73.6-97.7) |

| Objective | 100%,normal or near normal |

Table 3: Knee outcome scores in patients reviewed 4-6 years after surgery.

Discussion

An ACL tear is a common injury, accounting for 40 to 50% of all ligamentous knee injuries, especially in young patients involved in sporting activities [20]. Its incidence in the general population ranges from 1 in 3500 patients in the United States of America (USA) [21,22], to 34, 38 and 32 per 100 000 inhabitants in Norway, Denmark and Sweden respectively [15]. At the University Hospital of the West Indies the first open procedure was done in 1994. By 1998 arthroscopicassisted techniques were introduced and remain today as the gold standard. In this study only 73 patients underwent ACL reconstruction.

All patients underwent a similar surgical procedure whereby patella bone-tendon-bone graft was used exclusively and interference screws were used in all but four patients, who had staples for tibial side of the graft fixation. The graft choice is due to surgeon’s preference, but it is noted that four out of six studies found no statistical difference between patient groups where patella bone-tendon-bone graft was compared to 2- or 4- strand hamstring-tendon graft [23-29]. Controversies still exist as to which graft and surgical technique is superior in ACL reconstruction. When compared to different technologies, patella bone tendon bone autograft has been considered to be gold standard [25-30].

One of the major complaints of patients with chronic anterior cruciate-deficient knees is recurrent episodes of giving away and this causes significant restriction in players’ ability to perform sports that require many cutting and pivoting maneuvres [31]. As a result only 19-82% of these athletes reported to return to their pre-injury activity level and in some ended their sporting career [2,32]. Rehabilitation alone is only supported in those patients who are willing to modify their activity level and avoid pivoting sports [33].

In athletes with ACL tears, primary reconstruction gives the best chance to gain knee stability and allow athletes to return to sports as quickly as possible although reports suggest that even with reconstruction as low as 50% of athletes return to competition [7]. Reconstruction and rehabilitation rather than rehabilitation alone is more effective in achieving this goal [34,35]. Also by performing surgery the risk for further injury of the menisci and cartilage is decreased [31]. Patients opting for rehabilitation alone have up to three year return to pre-injury level [31]. Frobell et al. [36] conducted a randomized trial of treatment for acute ACL tears and concluded that rehabilitation in adjunct with ACL reconstruction in young active adults was not superior to rehabilitation plus delayed ACL reconstruction.

The definition of “return to sport” varies widely. A meta-analysis by Ardern et al. [37] of 5770 participants from 48 studies, noted this definition referred to return-to-any-sport or return-to-pre-injury level or return-to-competitive-sport. These results show that most persons are able to return to sports after surgery, but are less likely to return to their pre-injury level of participation, especially if they are competitive level athletes. Hence patients must be counseled accordingly before surgery. In our study return-to-any-sport was 78%, return-to-preinjury- level was 66% and return-to-competitive-sport was 47%. Similar outcomes were seen in the systematic review by Ardern et al. [37] of 82%, 63% and 44% respectively [37]. Using the Tegner activity scale, 44% of patients returned to their pre-injury level in this study. This is similar to other retrospective studies which range from 33 to 100% [38-44]. In this study the average time to return to sports was 9 months (range 2-19 months). This was longer than anticipated but similar to findings in other study reviews where the average return to sports was 7.3 months (range 2-24 months) [37,45-53].

The average knee functional outcome scores in patients reviewed prospectively one year after surgery were noted to be high. However despite 100% of patients having normal or near normal knees, not all patients returned to sports. Even though this finding occurred in a small study population it follows the general trend in other larger studies where high knee function outcome scores do not necessarily correlate with an athlete returning to sport [37]. Other factors at play in this study that prevented return to sports included fear of re-injury (kinesiophobia), and change in lifestyle. Lack of motivation and sports confidence were cited in other studies [54-56]. As a result consultation with sports psychologists, and use of psychological outcome scores have been implemented to predict and help manage, patient’s likelihood to have fear of re-injury [54].

Those patients who were reviewed four to six years after surgery had good knee outcome scores eight out of nine patients were still playing sports. These 8 patients returned to sports less than one year after surgery (range 4-9 months). This is in contrast to most studies where patients initially returned to their pre-injury level 1-year after surgery but did not continue at this same level of participation [55,57]. The good result in this study may be because the patients were recreational athletes, thus less likely to place high stress on their surgically reconstructed knee as competitive level athletes.

This study had some significant limitations. The retrospective nature of a portion of this study could have led to recall bias. The lack of power due to the small patients’ numbers likely impacted on the lack of statistical significance when comparing outcome variables between patients who returned and did no return to sports. For this same reason further analysis was not done to assess the impact of patient age, gender, the presence of other concomitant intra-articular injuries with their anterior cruciate ligament tear and chronicity of the injury. The use of the Tegner activity scale also had its specific limitations as it lacked sports such as cricket, and not all sports included had slots for both recreational and competitive participation. This may have led to misinterpretation of the patient’s true participation level. This study however marks the beginning of an anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction registry and these issues can be addressed in time to come as more patients undergo surgery.

Conclusion

Reconstruction of ACL is the management of choice for patients who sustain an ACL tear and wish to return to sports. Good short and long-term knee outcome scores were noted in this study, but only 78% returned to any sport with 63% returning to their pre-injury level. This trend, which reflects the international literature results, points to the fact that other factors such as kinesiophobia need to be addressed in order to achieve our goal of returning players to their respective sports.

This study represents the first set of patients that were enrolled in an ACL reconstruction database registry. Further research and analysis will help to address other issues such as the impact of surgical adjunct (meniscal and cartilage) procedures, patient gender and injury chronicity on knee function and patient ability to return to sport.

References

- Woo SL, Wu C, Dede O, Vercillo F, Noorani S (2006) Biomechanics and anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Orthop Surg Res 1: 1-9.

- Myklebust G, Holm I, Maehlum S, Engebretsen L, Bahr R (2003) Clinical, functional, and radiologic outcome in team handball players 6 to 11 years after anterior cruciate ligament injury: a follow-up study. Am J Sports Med 31: 981- 989.

- Griffin LY (2000) Noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injuries: risk factors and prevention strategies. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 8: 141-150.

- Miyasaka KC, Daniel D, Stone ML, Hirshman P (1991) The incidence of knee ligament injuries in the general population. Am J Knee Surg 4: 3-8.

- Paxton ES, Kymes SM, Brophy RH (2010) Cost-effectiveness of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a preliminary comparison of single-bundle and double-bundle techniques. Am J Sports Med 38: 2417-2425.

- Hart AJ, Buscombe J, Malone A, Dowd GS (2005) Assessment of osteoarthritis after reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament: a study using single-photon emission computed tomography at ten years. J Bone Joint Surg Br 87: 1483-1487.

- Swart E, Redler L, Fabricant PD, Mandelbaum BR, Ahmad CS, et al. (2014) Prevention and screening programs for anterior cruciate ligament injuries in young athletes: a cost-effectiveness analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 96: 705-711.

- Sutton KM, Bullock JM (2013) Anterior cruciate ligament rupture: differences between males and females. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 21: 41-50.

- Bradley JP, Klimkiewicz JJ, Rytel MJ, Powell JW (2002) Anterior cruciate ligament injuries in the national football league: epidemiology and current treatment trends among team physicians. Arthroscopy 18: 502-509.

- Hurd WJ, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L (2008) Influence of age, gender, and injury mechanism on the development of dynamic knee stability after acute ACL rupture. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 38: 36-41.

- Ireland M (1999) Anterior cruciate ligament injury in female athletes: epidemiology. Journal of Athletic Training 34: 150-154.

- Arendt E, Dick R (1995) Knee injury patterns among men and women in collegiate basketball and soccer. NCAA data and review of literature. Am J Sports Med 23: 694-701.

- Hutchinson MR, Ireland ML (1995) Knee injuries in female athletes. Sports Med 19: 288-302

- Granan LP, Forssblad M, Lind M, Engebretsen L (2009) The Scandinavian ACL registries 2004-2007: baseline epidemiology. Acta Orthopaedica 80: 563-567.

- Prodromos CC, Han Y, Rogwowski J, Joyce B, Shi K (2007) A meta-analysis of the incidence of anterior cruciate ligament tears as a function of gender, sport, and a knee injury-reduction regimen. Arthroscopy 23: 1320-1325.

- Matava MJ, Howard DR, Polakof L, Brophy RH (2014) Public perception regarding anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 96: e85.

- James I (2012) Summary of clinical outcome measures for sports-related knee injuries. Final report: AOSSM Outcomes Task Force.

- Council of Europe (1993) The European Sports Charter, Brussels: Council of Europe.

- Gianotti SM, Marshall SW, Hume PA, Bunt L (2009) Incidence of anterior cruciate ligament injury and other knee ligament injuries: a national population-based study. J Sci Med Sport 12: 622-627.

- Gordon MD, Steiner ME (2004) Anterior cruciate ligament injuries. In: Garrick JG (ed.) Orthopaedic knowledge update sports medicine. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, Rosemont, USA, pp: 169.

- Albright JC, Carpenter JE, Graf BK, Richmond JC (1999) Knee and leg: soft tissue trauma (6th edn). In: Beaty JH (ed.) Orthopaedic knowledge. American Academy of orthopaedic Surgeons, Rosemont, USA, pp: 533.

- Reinhardt KR, Hetsroni I, Marx RG (2010) Graft selection for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a level I systematic review comparing failure rates and functional outcomes. Orthop Clin North Am 41: 249-262.

- Anderson AF, Snyder RB, Lipscomb AB (2001) Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. A prospective randomized study of three surgical methods. Am J Sports Med 29: 272-279.

- Xiaoyun P, Hong W, Lide W, Tichi G (2012) Bone–patellar tendon–bone autograft versus LARS artificial ligament for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. European Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery & Traumatology 23: 819-823.

- Feller JA, Webster KE (2003) A randomized comparison of patellar tendon and hamstring tendon anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med 31: 564- 573.

- Webster KE, Feller JA, Hameister KA (2001) Bone tunnel enlargement following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a randomized comparison of hamstring and patellar tendon grafts with 2-year follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 9: 86-91.

- Taylor DC, DeBerardino TM, Nelson BJ, Duffey M, Tenuta J, et al. (2009) Patellar tendon versus hamstring tendon autografts for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a randomized controlled trial using similar femoral and tibial fixation methods. Am J Sports Med 37: 1946-1957.

- Maletis GB, Cameron SL, Tengan JJ, Burchette RJ (2007) A prospective randomized study of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a comparison of patellar tendon and quadruple-strand semitendinosus/gracilis tendons fixed with bio absorbable interference screws. Am J Sports Med 35: 384-394

- Chechik O, Amar E, Khashan M, Lador R, Eyal G, et al. (2013) An international survey on anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction practices. Int Orthop 37: 201-206.

- Noyes FR, Mooar PA, Matthews DS, Butler DL (1983) The symptomatic anterior cruciate-deficient knee. Part I: the long-term functional disability in athletically active individuals. J Bone Joint Surg Am 65: 154-162.

- Roos H, Ornell M, Gardsell P, Lohmander LS, Lindstrand A (1995) Soccer after anterior cruciate ligament injury--an incompatible combination? A national survey of incidence and risk factors and a 7-year follow-up of 310 players. Acta Orthop Scand 66: 107-112.

- Kostogiannis I, Ageberg E, Neuman P, Dahlberg LE, Fridén T, et al. (2008) Clinically assessed knee joint laxity as a predictor for reconstruction after an anterior cruciate ligament injury: a prospective study of 100 patients treated with activity modification and rehabilitation. Am J Sports Med 36: 1528-1533.

- Muaidi QI, Nicholson LL, Refshauge KM, Herbert RD, Maher CG (2007) Prognosis of conservatively managed anterior cruciate ligament injury: a systematic review. Sports Med 37: 703-716.

- Kessler MA, Behrend H, Henz S, Stutz G, Rukavina A, et al. (2008) Function, osteoarthritis and activity after ACL-rupture: 11 years follow-up results of conservative versus reconstructive treatment. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 16: 442-448.

- Frobell RB, Roos EM, Roos HP, Ranstam J, Lohmander LS (2010) A randomized trial of treatment for acute anterior cruciate ligament tears. N Engl J MedL 363: 331-342.

- Ardern CL, Webster KE, Taylor NF, Feller JA (2011) Return to sport following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the state of play. Br J Sports Med 45: 596-606.

- Fabbriciani C, Milano G, Mulas PD, Ziranu F, Severini G (2005) Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with doubled semitendinosus and gracilis tendon graft in rugby players. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 13: 2-7.

- Aglietti P, Buzzi R, Menchetti PM, Giron F (1996) Arthroscopically assisted semitendinosus and gracilis tendon graft in reconstruction for acute anterior cruciate ligament injuries in athletes. Am J Sports Med 24: 726-731.

- Jerre R, Ejerhed L, Wallmon A, Kartus J, Brandsson S, et al. (2001) Functional outcome of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in recreational and competitive athletes. Scand J Med Sci Sports 11: 342-346.

- Lee DY, Karim SA, Chang HC (2008) Return to sports after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction - a review of patients with minimum 5-year follow-up. Ann Acad Med Singapore 37: 273-278.

- Gobbi A, Tuy B, Mahajan S, Panuncialman I (2003) Quadrupled bone-semitendinosus anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a clinical investigation in a group of athletes. Arthroscopy 19: 691-699.

- Heijne A,Axelsson K, Werner S, Biguet G (2008) Rehabilitation and recovery after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: patients' experiences. Scand J Med Sci Sports 18: 325-335.

- Hasebe Y (2005) Anterior-cruciate-ligament reconstruction using doubled hamstring-tendon autograft. J Sports Rehabil 14: 279-293.

- Mikkelsen C, Werner S, Eriksson E (2000) Closed kinetic chain alone compared to combined open and closed kinetic chain exercises for quadriceps strengthening after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with respect to return to sports: a prospective matched follow-up study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 8: 337-342.

- Nakayama Y, Shirai Y, Narita T, Mori A, Kobayashi K (2000) Knee functions and a return to sports activity in competitive athletes following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Nippon Med Sch 67: 172-176.

- Middleton KK, Hamilton T, Irrgang JJ, Karlsson J, Harner CD, et al. (2014) Anatomic anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction: a global perspective. Part 1. Knee Surgery Sports Traumatology Arthroscopy 22: 1467-1482.

- Shelbourne KD, Gray T (1997) Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with autogenous patellar tendon graft followed by accelerated rehabilitation. A two- to nine-year followup. Am J Sports Med 25: 786- 795.

- Zaffagnini S, Bruni D, Russo A, Takazawa Y, LoPresti M, et al. (2008) ST/G ACL reconstruction: double strand plus extra-articular sling vs. double bundle, randomized study at 3-year follow-up. Scand J Med Sci Sports 18: 573-581.

- Bak K, Jørgensen U, Ekstrand J, Scavenius M (2001) Reconstruction of anterior cruciate ligament deficient knees in soccer players with an iliotibial band autograft. A prospective study of 132 reconstructed knees followed for 4 (2-7) years. Scand J Med Sci Sports 11: 16-22.

- Colombet P, Allard M, Bousquet V, de Lavigne C, Flurin PH, et al. (2002) Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using four-strand semitendinosus and gracilis tendon grafts and metal interference screw fixation. Arthroscopy 18: 232-237.

- Shelbourne KD, Urch SE (2000) Primary anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using the contralateral autogenous patellar tendon. Am J Sports Med 28: 651- 658.

- Webster KE, Feller JA, Lambros C (2008) Development and preliminary validation of a scale to measure the psychological impact of returning to sport following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery. Phys Ther Sport 9: 9-15.

- Kvist J, Ek A, Sporrstedt K, Good L (2005) Fear of re-injury: a hindrance for returning to sports after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 13: 393-397.

- Ardern CL, Taylor NF, Feller JA, Webster KE (2012) Return-to-sport outcomes at 2 to 7 years after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery. Am J Sports Med 40: 41-48.

- Wiggins AJ, Grandhi RK, Schneider DK, Stanfield D, Webster KE, et al. (2016) Risk of Secondary Injury in Younger Athletes After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med.

- Heijne A, Hagströmer M, Werner S (2015) A two- and five-year follow-up of clinical outcome after ACL reconstruction using BPTB or hamstring tendon grafts: a prospective intervention outcome study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 23: 799-807.

- Brophy RH, Schmitz L, Wright RW, Dunn WR, Parker RD, et al. (2012) Return to Play and Future ACL Injury Risk After ACL Reconstruction in Soccer Athletes From the Multicenter Orthopaedic Outcomes Network (MOON) group. Am J Sports Med 40: 2517-2522.

Relevant Topics

- Aminoacid Suppliments

- Bodybuilding Nutrition

- Clinical Sports Nutrition

- Creatine Sports Nutrition

- Diet

- Fitness Nutrition

- Food and Nutrition

- Gym Suppliments

- Herbal Suppliments

- Micronutrients

- Natural Suppliments

- Nutrition Sport Fitness

- Nutritional Health

- Protein Diet

- Protein Suppliments

- Sports Nutrition Suppliments

- Vitamin Supplement

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 12499

- [From(publication date):

June-2016 - Jul 13, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 11561

- PDF downloads : 938