Turnover Intention of Health Workers in Public-Private Mix Partnership Health Facilities: A Case of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Received: 07-May-2019 / Accepted Date: 29-May-2019 / Published Date: 07-Jun-2019 DOI: 10.4172/2161-1165.1000374

Abstract

Background: Turnover intention is defined as a conscious and deliberate willingness to leave an organization. Employees who are committed to an organization internalize the organizational goals. The purpose of this study was to determine the magnitude of staff turnover and assess the relationships among organizational commitment, turnover intention and job satisfaction of health workers engaged in Public Private Mix health facilities.

Method: This research employed a cross-sectional study design. The study population of this study was all health workers employed in private health facilities in Addis Ababa, capital city of Ethiopia. To this end, four hundred forty-seven record reviewed and one hundred health professionals which participated in the study, were selected from forty-five health facilities using simple random sampling technique. The researcher collected the relevant data from health workers using Brayfield and Rothe’s index of job satisfaction survey tools and Meyer and Allen’s items of Affective. Continuance and Normative organizational commitment and intention to quit current job were measured using three items Lance inventory. The researchers analyzed the data using mean, standard deviation, correlation, linear regression and Analysis of Variance (one-way ANOVA).

Results: In forty-five PPM surveyed health facilities, out of 474 employees the magnitude of staff turnover was 24 percent. Moreover, almost half of them, (46%) want to leave their current job. The results showed that there was evidence of positive correlation between health workers’ job satisfaction and their organizational (r=0.574, p<0.01) affective commitment (r=0.596, p<0.01), normative commitment (r=0.504, p<0.01), continuance commitment (r =0.204, p<0.05). Likewise, there is a positive relation between turnover intention and continuance commitment (r=0.376, p<0.01). However, turnover intention is negatively correlated with job satisfaction (r=-0.328, p<0.01), marital status (r=-0.332, p<0.01), and age (r=-0.268, p<0.01). Similarly, gender is negatively correlated with age (r=-338, p<0.01), and level of education (r=-0.331, p<0.01). In this study, the researcher found no statistical significant variation in turnover intention between males and females (p>0.05). The mean score of turnover intensions were computed against mean score of job satisfaction and organizational commitment. The results showed that, beta (β) coefficient from the general linear regression, adjusted models an increase in mean turnover intention score per unit increase in continuance commitment score at β 0.432 (0.197, 0.500), p<0.05. While, an increase in mean turnover intention score per unit decreases in job satisfaction and affective commitment score β -0.318(-0.399, -0.100) and β -0.467(-0.477, -0.215), p<0.05, respectively.

Conclusions: Consequently, per this finding it was concluded that there is high staff turnover and intention to turnover in public private mix health facilities and the level of health professionals’ organizational commitment can be enhanced by creating a more satisfying working environment. Therefore, the public health sector should strive to improve the work environment of the private sector and work closely with the private sector on staff retention mechanisms.

Keywords: Turnover intention; Organizational commitment; Job satisfaction; Public private mix; Ethiopia

Abbreviations

AC: Affective Commitment; ANOVA: Analysis of Variance; CC: Continuance Commitment; FMHACA: Food, Medicine, and Health Care Authority; NC: Normative Commitment; PPM: Public Private Mix; FMOH: Federal Ministry of Health; PHSP: Private Health Sector Program; SSA: Sub Saharan Africa; WHO: World Health Organization

Introduction

A World Health Organization (WHO) report published in 2006, drew global attention to the Human Resources for Health (HRH) crisis, manifested by shortages and imbalances in the health workforce undermining the performance of health systems and exercising adverse impacts on the ability of many countries to promote and enhance the health of their population [1]. The global crisis on HRH challenges almost all developing countries to meet their commitment to create access to effective public health interventions [2].

According to the WHO estimates, globally, there is a shortage of 2.4 million health workforce (doctors, nurses and midwives) in 57 countries. Out of these countries, the majority, 36 Sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries shoulder critical shortage of health workforce [1]. Healthcare service is vital, and critical to saving lives around the world. WHO estimates state that a desired HRH threshold ratio is 2.28 health workers per 1000 population [1]. Among SSA countries, Ethiopia is far below the threshold with an estimated ratio of 0.246 health workers per 1000 population [3].

Ethiopia's gains in the health sector in the past few years have earned the country global recognition. In recognition of the complexity of challenges in the context of the rapidly increasing demand for healthcare services, the Ethiopian government is committed to engaging the private health sector in creating productive public-private partnerships and harnessing the sector to meet its ambitious health goal of creating essential healthcare service to its citizens. In its effort to enhance the engagement of the private health sector in addressing high impact public health challenges, the Ethiopian ministry of health enacted a strategic framework in 2013 [4]. The framework highlights and underlines the important role and contribution of the private sector in health development and defines an institutional framework within which to coordinate, implement, monitor, evaluate and enrich the public-private partnership, and address public-private partnership in health concerns by taking policy decisions. By partnering and collaborating with the private sector, the government envisages leveraging resources to improve health outcomes in the country in terms of accessibility, efficiency, equity, sustainability and quality of health sector investment [4].

Healthcare can be provided through public and private providers. Public healthcare is usually provided by governments through national healthcare systems while private healthcare can be provided through 'for profit', self-employed practitioners and 'not for profit', nongovernment providers, including faith-based organizations [4].

The rising magnitude of healthcare workers’ turnover has a negative impact on the sector, the providers and the community. Retention of healthcare workers in private health facilities is challenging as the supply of experienced workforce is scarce, learning and training costs are high as well as various other related factors. Retention of experienced and trained staff should be among the priority tasks for the private health sector. Therefore, interruption of quality assured services will be a challenge for the customers, the private sector, the public sector and the community at large.

There are 62 public and 608 private facilities in Addis Ababa City, with high potential health services coverage [5]. In the last decade, private health facilities are talking share of providing users fee exempt public health services through the established public-private mix partnership. There are 45 PPM Private-Public Mix (PPM) facilities committed to providing Tuberculosis (TB) and Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) services in the city [6]. Among developing countries, Addis Ababa is a capital city where private health sector flourishing, and thousands of healthcare workers are engaged in the sector. Staff turnover is a major challenge facing both the private and public health sectors. There is also little information about the private sector employees' organizational commitment, job satisfaction and their intention to turnover.

Therefore, the objective of this study is to determine the magnitude of staff turnover, satisfaction and organizational commitment. In addition, the study aims to identify factors influencing intention to turnover of staff.

Concept of turnover, job satisfaction and organizational commitment

Health workers are the central element in the health system and engage in various important responsibilities. The overall performance of health facilities depends upon health professionals and ultimately their level of commitment and job satisfaction. Understanding behaviors and attitudes of staff in these organizations, therefore, needs attention [7]. The study of behaviors within the organizational setting has highlighted critical variables that are supportive or detrimental to the performance of the workforce. This notion holds true while focusing on quality of human resources that is the major factor which contributes significantly to the organizational success [8].

Job satisfaction is a crucial issue for all organizations whether public or private, or working in advanced or underdeveloped countries [9]. Job satisfaction affects the health of staff, their efficiencies, labour relationships in the organization and the organization ’ s overall efficiency. Job satisfaction has individual, organizational and social outcomes. According to Brown and Sargeant, these outcomes may sometimes be positive or negative [10]. For example, they may represent more negative effects such as low efficiency, work stoppage, absenteeism, tardiness or theft. On the contrary, they may present more positively via high efficiency, loyalty, punctuality, self-devotion and commitment.

Job satisfaction amongst health workers is a multifaceted construct which is imperative for the retention of these professionals and is a significant determinant of their commitment as well as a contributor to health facilities’ effectiveness. Research, however, has revealed a wide range of differences contributing to job satisfaction amongst health workers [9]. In the process of development of any health system around the world, job satisfaction is vital.

There are several factors affecting organizational commitment, however, it is possible to classify these as an individual, organizational and non-organizational (environmental) factors. Individual factors often include job expectations, physiological contracts and personal characteristics (gender, marital status, seniority, position, education, race, and social culture).

Literature suggests that individuals become committed to organizations for a variety of reasons, including an affective attachment to the values of the organization, a realization of the costs involved with leaving the organization, and a sense of obligation to the organization [11]. Research recommends that establishing a higher level of organizational commitment can lower degrees of both absence and turnover [12]. Organizational commitment is partially the effect of intrinsic personal characteristics and partially the consequence of how people understand the institution and their instant job function [13].

The three-component model of commitment developed by Meyer and Allen arguably dominates organizational commitment research [11]. They discuss organizational commitment as emotional, continuity and normative responses. Affective commitment refers to an employee ’ s emotional attachment to identification with and involvement in a particular organization. Workers stay with an establishment because they need to. The employee develops with the organization primarily via positive work experiences. Continuance commitment refers to commitment based on the costs that the employee associates with leaving the organization. Normative commitment refers to the employee’s feelings of obligation to stay with the organization [14].

The foundation of job satisfaction theory was introduced by Maslow [15,16] with a five-stage hierarchy of human needs, now recognized as the deprivation proposition. However, much of the job satisfaction research has focused on employees in the public sector. The motivation to investigate the degree of job satisfaction arises from the fact that a better understanding of employee satisfaction is desirable to achieve a higher level of motivation that is directly associated with patient satisfaction.

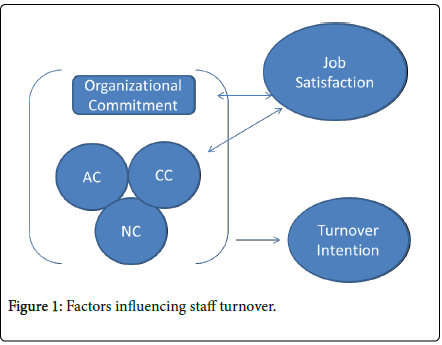

Organizations’ efficiency depends to a large extent on the morale of its employees. Behavioral and social science research suggests that job satisfaction and job performance are correlated. Job satisfaction and morale among medical practitioners is a current concern worldwide. Poor job satisfaction leads to increased turnover of health workers, adversely affecting medical care job satisfaction. Consequently, by creating an environment that promotes job satisfaction, a health-care manager can develop employees who are motivated, productive, and fulfilled. This, in turn, will contribute to higher quality patient care and patient satisfaction (Figure 1).

Ajayi as cited in Geleto et al. [17,18] confers human factor is the most critical resource for any organization. It organizes and utilizes other resources for the production of the intended outputs. For the optimum performance, the workforce needs to be regularly motivated through either financial or non-financial incentives to get satisfied with their work. Several reasons have been attributed to the health workforce crisis in Sub-Sahara Africa (SSA). These include poor work environment; a work environment comprises the physical geographical location, physical surroundings and conditions of service, management style, chemical and biological environment among other things.

Impacts of staff turnover

Retention of workers versus turnover of workers is an issue in any industry today. Lack of advancement, poor salary, and work overload, staff shortages, organizational culture and nature of work are considered as the major challenges faced by healthcare workers in general. There are four types of turnovers. These are voluntary, involuntary, functional and dysfunctional [19]. If an employer is said to have a high turnover rate relative to its competitors, it means that employees of that company have a shorter average tenure than those of other companies in the same industry. High turnover may be harmful to a company’s productivity if skilled workers are leaving frequently and the workers' population contains a high percentage of novices.

Employees are important in any running of a business; without them, the business would be unsuccessful. Providing a stimulating workplace environment which fosters happy, motivated and empowered individuals, lowers employee turnover and absence rates. Promoting a work environment that fosters personal and professional growth promotes harmony and encouragement on all levels, so the effects are felt company wide.

Research Methodology

Research design

This research employed a cross-sectional study design and data was collected from January–March 2017.

Study setting

Addis Ababa is the Capital city of Ethiopia. It has ten sub cities and one hundred and sixteen woredas. There are 62 public and 608 private health facilities with almost 100 percent potential health service coverage. There are 45 private health facilities engaged in providing public health services (tuberculosis diagnosis and treatment, HIV test and chronic care and family planning services in the city [5,6]. All public-private partner facilities have trained health care providers.

Target population

The target groups were all healthcare workers employed in targeted private health facilities. Consisting of nurses, public health officers, laboratory personnel and pharmacy personnel.

Sampling size and sampling procedure

All forty-five private health facilities working through public-private mix approaches for public health services were selected for this study. From these health facilities, one hundred employees were selected by simple random sampling technique. The questionnaires were administered in the form of one to one interviewer data collection method.

The sample size was all 474 Personnel files and 100 healthcare workers, which were allocated to each professional category based on population proportion to size. Due to time and financial constraints the sample size was restricted to 100. Study participants were selected using simple random sampling techniques after employing the payroll as a sampling frame.

Data collection method

Comprehensive research instruments were developed in English. The tools were pre-tested in a similar setup in Addis Ababa. Amendments of the tools were made before data collection started.

Primary data: To determine the intention to staff turnover and identify factors influencing it, primary data were collected through a questionnaire. The data collection tools were adapted for this study from published scientific literatures [11,20,21]. The questionnaire addressed variables related to employees’ attitudes, their perception of organizational commitment and intention to quit their current job. The data collection tools were administered to the various groups of employees of the organizations.

Secondary data: Before collecting primary data, managers of each organization were interviewed to ascertain the average number of staff employed who attended training to facilitate public health programs. Data abstraction forms were used to collect data on average number of employees and numbers of health care workers who left their job in one year.

Data interpretation and analysis

In order to ensure logical completeness and consistency of responses, data editing was carried out each day by the researcher. Identified mistakes and data gaps were rectified as soon as possible. Once editing is done, data entry followed using computer database with statistical software for social science (SPSS IBM Version 20). Descriptive analysis using frequencies, percentages, tables and graphs was conducted to determine the proportion of respondents who left their job in the previous twelve months and various responses were measured.

Cross-tabulations and univariable logistic regression were analyzed to determine the significant relationship and its strength using Crude Odds Ratios (COR), and chi-square (X2) test employed for categorical variables. In uni-variable logistics regression analysis those variable with p-value <0.25 considered as a nominee variable to develop a model for multivariable logistic regression. Statistical test results were reported using Adjusted Odds Ratios (AOR) with 95% Confidence Interval (CI). Statistical significance tests, the cut-off value set is p<0.05 as this is the accepted statistically significant.

To measure the overall satisfaction of health care providers who are working in public-private partnership facilities, data were collected using the five items of Brayfield and Rothe index of job satisfaction [20]. In addition, organizational culture was measured by collecting data on 12 items of Mayer and Allen [11] affective, continuance and normative organizational commitment. Furthermore, intention to quit current job was measured using three items Lance inventory. All the questions were developed based on a five-point Likert scale ranging from very unlikely or strongly disagree (1) to certainly or strongly agree (5). The overall scores for each category were added up and those scored above the mean values were labeled as satisfied, had high organizational commitment and low turnover intention, otherwise, they were classified as dissatisfied, had low organizational commitment and high turnover intention [22].

Reliability

The tool was piloted using the result of 10 (5 Males and 5 Females) employees of public-private mix private health facilities in Addis Ababa. The responses of each participant were scored, and the reliability of the tool was determined using Cronbach ’ s Alpha. According to the alpha, value of more than 0.6, shows that the scale can be considered reliable [23]. The tool has twenty questions i.e. 12 questions for organizational commitment, 5 questions for job satisfaction and 3 questions for turnover intention. The result shows that the Cronbach’s alpha ranges from 0.730 to 0.890 which show the scale is reliable.

Ethical consideration

Ethical clearance was sought and obtained from Indra Gandhi National Open University Institutional Review Board (IRB) and research ethics committee. Owners and head of private health facilities; they are informed about the purpose of the research. The full consent of participants was sought. Participants were informed that their participation is based on their free will, moreover, they are informed about as it is their right to terminate anytime or skip some questions. The result will benefit health care workers, private health facilities owners and policymakers.

Results

A total of 474 health workers were employed in forty-five surveyed PPM facilities in Addis Ababa City. Of the surveyed facilities one was MCH speciality center, five (11.11%) were medium clinics; nine (20.0%) were faith-based organizations Health Centers, and 30 (66.66%) were higher clinics. The above number of staff availability in surveyed facilities is in line with FMHACA recommendations for each level of health facilities. Description of research participants using biodemographic characteristics i.e. marital status educational achievements, profession and current work assignment in the facilities are presented below: Slightly higher than one third (35 %) of respondents were falling in the age category between 28 and 35 years, followed by (30%) between 20 and 27 years (Table 1).

| Variable | Characteristics | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 37 | 37 | |

| Married | 59 | 59 | |

| Widowed | 2 | 2 | |

| Divorced | 2 | 2 | |

| Educational status | |||

| Certificate | 4 | 4 | |

| Diploma | 40 | 40 | |

| BSc | 39 | 39 | |

| MSc | 17 | 17 | |

| Profession | |||

| Nurse | 47 | 47 | |

| Health Officer | 39 | 39 | |

| Medical Doctor | 8 | 8 | |

| Laboratory Technician | 2 | 2 | |

| Other | 4 | 4 | |

| Department | |||

| Emergency | 14 | 14 | |

| Outpatients | 42 | 42 | |

| Inpatients | 16 | 16 | |

Table 1: Background characteristics of respondents.

Studies revealed that the presence of the leadership between the demographic variable like marital status and intention to leave [23]. In this study, close to two-thirds (59%) of study participants are married which has a positive predictive value to staff retention while one-third are single with higher level of intention to turnover. With regards to the educational status, slightly lower than two-thirds (56%) of participants were achieved BSc degree or more. On the other hand, a little lower than (44%) of the study participants were achieved diploma level education, this might be one of the factors for staff turnover either looking better earnings or pursuing educational career.

Job satisfaction

| Question | Strongly disagree | Disagree | No opinion | Agree | Strongly agree | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freq (%) | Freq (%) | Freq (%) | Freq (%) | Freq (%) | Mean | SD | |

| I feel fairly satisfied with my present job | 20 (20) | 21 (21) | 17 (17) | 39 (39) | 3 (3) | 2.84 | 1.22 |

| Most days I am enthusiastic about my work | 19 (19) | 24 (24) | 23 (23) | 32 (32) | 2 (2) | 2.74 | 1.16 |

| Each day of work seems like it will never end | 16 (16) | 19 (19) | 26 (26) | 35 (35) | 4 (4) | 2.92 | 1.16 |

| I find real enjoyment in my work. | 17 (17) | 26 (26) | 16 (16) | 33 (33) | 8 (8) | 2.89 | 1.26 |

| I consider my job rather Unpleasant | 9 (9) | 24 (24) | 17 (17) | 40 (40) | 10 (10) | 3.18 | 1.17 |

| Overall Job Satisfaction | 2.95 | 0.84 | |||||

Table 2: Respondents’ assessment of their level of job satisfaction, Addis Ababa 2017.

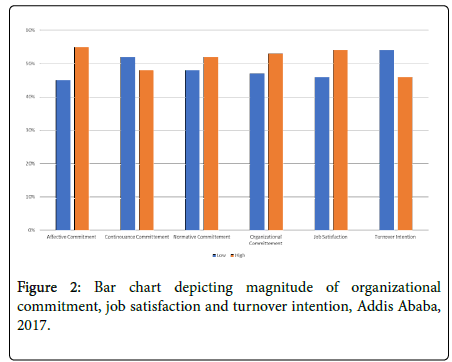

As Presented in Table 2, employees were asked about their job satisfaction and the weighted average score was: 1) Employ assessment on their feeling as there were fairly well satisfied with their present job (2.84); 2) They were enthusiastic about their work (2.74); 3) Employ were felt as each day will never end (2.92); 4) Employ feel as they were enjoying their work (2.89); and 5) Employ were considered their job rather unpleasant (3.18). Based on the result, from one- third to half (31% to 50%) respondents were satisfied with their current job. The overall magnitude of job satisfaction was 54% (Figure 2). This showed that slightly higher than half of respondents scored above the mean satisfaction score.

Organizational commitment

Employs were asked about their organizational commitment with three domains i.e. affective commitment, continuance commitment and normative commitment (Table 3). With regards to weighted average score of four categories of affective commitment was: 1) Employs who are happy to spend the rest of their carrier in the current organization (2.46); 2) Employs who feel their organization problems as their own (2.49); 3) Employs who are feeling “part of the family” in the organization (2.49); and 4) Employs who feel “ emotionally attached” to the current employer organization (2.50). The overall average affective commitment score was 2.48 and 55% of the research participants had a higher score than the reported average score.

| Question | Strongly disagree | Disagree | No opinion | Agree | Strongly agree | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freq (%) | Freq (%) | Freq (%) | Freq (%) | Freq (%) | Mean | SD | |

| I would be very happy to spend the rest of my career with this organization | 30 (30) | 25 (25) | 17 (17) | 25 (25) | 3 (3) | 2.46 | 1.24 |

| I really feel as if this organization's problems are my own | 22 (22) | 37 (37) | 19 (19) | 14 (14) | 8 (8) | 2.49 | 1.22 |

| I feel like a part of the family at my organization | 32 (32) | 23 (23) | 17 (17) | 20 (20) | 8 (8) | 2.49 | 1.33 |

| I feel emotionally attached to this organization | 26 (26) | 34 (34) | 13 (13) | 18 (18) | 9 (9) | 2.5 | 1.29 |

| Overall Affective Commitment | 2.48 | 1,09 | |||||

| Right now, staying with my organization is a matter of necessity as much as a desire | 8 (8) | 16 (16) | 15 (15) | 47 (47) | 14 (14) | 3.43 | 1.15 |

| It would be very hard for me to leave my organization right now, even if I wanted to | 16 (16) | 19 (19) | 17 (17) | 34 (34) | 14 (14) | 3.11 | 1.31 |

| Too much of my life would be disrupted if I decided I wanted to leave my organization | 18 (18) | 22 (22) | 18 (18) | 31 (31) | 11 (11) | 2.95 | 1.3 |

| One of the few negative consequences of leaving this organization would be the scarcity of available alternatives | 13 (13) | 15 (15) | 21 (21) | 43 (43) | 8 (8) | 3.18 | 1.18 |

| Overall Continuance Commitment | 3.28 | 1.62 | |||||

| Even it was to my advantage, I do not feel it would be right to leave my organization now | 14 (14) | 35 (35) | 22 (22) | 25 (25) | 4 (4) | 2.7 | 1.11 |

| I would not leave my organization right now because I have a sense of obligation to the people in it | 21 (21) | 29 (29) | 16 (16) | 27 (27) | 7 (7) | 2.7 | 1.6 |

| I owe a great deal to my organization | 20 (20) | 27 (27) | 16 (16) | 32 (32) | 5 (5) | 2.75 | 1.24 |

| I would feel guilty if I left my organization now | 22 (22) | 34 (34) | 18 (18) | 19 (19) | 7 (7) | 2.55 | 1.22 |

| Overall Normative Commitment | 2.67 | 1.03 | |||||

| Overall Organizational Commitment | 2.81 | 0.92 | |||||

Table 3: Respondents’ assessment of their affective, continuance and normative commitment Addis Ababa, 2017.

Continuance commitment had four items. The weighted average score was: 1) Employs feel staying with the current employers as a matter of necessity (3.43); 2) Employs who feel it is hard to leave their current employer right now (3.11); 3) Employs who feel their life would be disrupted if they decided their organization (2.95); and 4) Employs who feel the negative consequences of leaving the organization organizations due to the scarcity of available alternatives (3.18). The overall average continuance commitment score was 3.28 and 48% of the research participants had a higher score than the reported average score.

The third organizational commitment with four items is normative commitment. The weighted average was: 1) Employs who feel despite they gain advantage, they would stay with their current employer (2.70); 2) Employs who feel to stay with the current organization for sense of obligation (2.70); 3) Employs who fell they owe a great deal to their organization (2.75); and 4) Employs who would feel guilty if they left the current organization (2.55). The overall average normative commitment score was 2.67 and 52% of the research participants had a higher score than this average score.

The organizational commitment of research participants was determined using all the twelve items. The average organizational commitment score was 2.81 and 53% of the research participants had a higher score than the reported average score.

Turnover intention

Employees were asked about their turnover intention as depicted in (Table 4). Employees which intended to leave their current organization (3.28); putting in genuine effort to find another job over the coming few months (3.27) and employees that think about quitting their job (3.15). Fifty-one percent of respondents had the intention to leave their current job. With regards to the intention to turnover, close to half, (48%-51%) are intending to leave their employers. The overall average turnover intention score was 3.23 and 46 percent of the research participants had a higher score than the reported average score. Therefore, studying the relationship between intention to turnover, job satisfaction, demographic factors and organizational commitment will help relevant parties and health facility owners design interventions.

| Question | Very unlikely | Unlikely | Neither | Likely | Very likely | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freq (%) | Freq (%) | Freq (%) | Freq (%) | Freq (%) | Mean | SD | |

| I intend to leave the organization | 10 (10) | 17 (17) | 22 (22) | 37 (37) | 14 (14) | 3.28 | 1.19 |

| I intend to make a genuine effort to find another job over the next few months | 11 (11) | 17 (17) | 21 (21) | 36 (36) | 15 (15) | 3.27 | 1.22 |

| I often think about quitting | 16 (16) | 16 (16) | 20 (20) | 33 (33) | 15 (15) | 3.15 | 1.31 |

| Overall Turnover Intention | 3.23 | 1.07 | |||||

Table 4: Respondents’ assessment of their level of turnover intention, Addis Ababa 2017.

As depicted below in Table 5, the mean score of turnover intention was compared and there is statically different mean score of turnover intention across: age (F (12,87)=2.196, p<0.05); marital status (F (12,87)=2.482, p<0.05); job satisfaction (F (12,87)=1.982, p<0.05); affective commitment (F (12,87)=3.199, p<0.05) and continuance commitment (F (12,87)=2.538, p<0.05).

| Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sigma | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender of participant | Between Groups | 4.492 | 12 | 0.374 | 1.589 | 0.11 |

| Within Groups | 20.498 | 87 | 0.236 | |||

| Total | 24.99 | 99 | - | |||

| Age in five categories | Between Groups | 26.961 | 12 | 2.247 | 2.195 | 0.019 |

| Within Groups | 89.039 | 87 | 1.023 | |||

| Total | 116 | 99 | - | |||

| Marital status of participant | Between Groups | 9.534 | 12 | 0.795 | 2.482 | 0.008 |

| Within Groups | 27.856 | 87 | 0.32 | |||

| Total | 37.39 | 99 | - | |||

| Level of education | Between Groups | 11.742 | 12 | 0.979 | 1.648 | 0.093 |

| Within Groups | 51.648 | 87 | 0.594 | |||

| Total | 63.39 | 99 | - | |||

| Field of study | Between Groups | 13.031 | 12 | 1.086 | 1.171 | 0.317 |

| Within Groups | 80.679 | 87 | 0.927 | |||

| Total | 93.71 | 99 | - | |||

| Service area | Between Groups | 18.759 | 12 | 1.563 | 1.518 | 0.133 |

| Within Groups | 89.601 | 87 | 1.03 | |||

| Total | 108.36 | 99 | - | |||

| Job satisfaction | Between Groups | 361.214 | 12 | 30.101 | 1.982 | 0.035 |

| Within Groups | 1321.296 | 87 | 15.187 | |||

| Total | 1682.51 | 99 | - | |||

| Affective commitment | Between Groups | 580.97 | 12 | 48.414 | 3.199 | 0.001 |

| Within Groups | 1316.67 | 87 | 15.134 | |||

| Total | 1897.64 | 99 | - | |||

| Continuance commitment | Between Groups | 413.397 | 12 | 34.45 | 2.538 | 0.006 |

| Within Groups | 1180.713 | 87 | 13.571 | |||

| Total | 1594.11 | 99 | - | |||

| Normative commitment | Between Groups | 264.126 | 12 | 22.011 | 1.336 | 0.213 |

| Within Groups | 1432.874 | 87 | 16.47 | |||

| Total | 1697 | 99 | - | |||

Table 5: Analysis of Variance (one-way ANOVA) between intentions to turnover and socio-economic, job satisfaction and organizational commitment.

The Table 6 below shows the correlation matrix illustrate that the presence of temporal relationship among variables of the study. Pearson ’ s correlation coefficient was determined to evaluate the relationship of the study variables. Job satisfaction was positively correlated with organizational commitment (r=0.574, p<0.01), affective commitment (r=0.596, p<0.01), normative commitment (r=0.504, p<0.01), and continuance commitment (r=0.204, p<0.05). Likewise, there is a positive relation between turnover intention and continuance commitment (r=0.376, p<0.01). This means that as health workers ’ job satisfaction increases, so does their organizational commitment. Similarly, there is a statistically significant positive relationship between health workers’ job satisfaction and the three domains of organizational commitment. However, turnover intention is negatively correlated with job satisfaction (r=-0.328, p<0.01), marital status (r=-0.332, p<0.01), and age (r=-0.268, p<0.01). Similarly, gender is negatively correlated with age (r=-338, p<0.01), and level of education (r=-0.331, p<0.01). This means that as level of health workers’ job satisfaction decreases, age decreases as well.

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 1 | |||||||||

| Age in five Categories | -0.338** | 1 | ||||||||

| Marital Status | 0.059 | 0.337** | 1 | |||||||

| Level of Education | -0.331** | 0.329** | 0.111 | 1 | ||||||

| Job Satisfaction | 0.083 | 0.094 | 0.102 | 0.088 | 1 | |||||

| Turnover Intention | 0.008 | -0.268** | -0.332** | -0.122 | -0.318** | 1 | ||||

| Organizational Commitment | 0.212* | 0.001 | 0.148 | -0.171 | 0.574** | -0.142 | 1 | |||

| Affective Commitment | 0.124 | 0.041 | 0.275** | -0.132 | 0.596** | -0.467** | 0.777** | 1 | ||

| Continuance Commitment | 0.210* | -0.106 | -0.152 | -0.142 | 0.204* | 0.376** | 0.602** | 0.037 | 1 | |

| Normative Commitment | 0.157 | 0.061 | 0.201* | -0.12 | 0.504** | -0.198* | 0.916** | 0.710** | 0.387** | 1 |

| **Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed), *Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed). • Perfect: If the value is near ± 1, then it said to be a perfect correlation: as one variable increases, the other variable tends to also increase (if positive) or decrease (if negative). • High degree: If the coefficient value lies between ±0.50 and ±1, then it is said to be a strong correlation. • Moderate degree: If the value lies between ±0.30 and ±0.49, then it is said to be a medium correlation. • Low degree: When the value lies below + 0.29, then it is said to be a small correlation. • No correlation: When the value is zero. |

||||||||||

Table 6: Correlation matrix of study variables.

As presented below (Table 7), the effect of job satisfaction and organizational commitment on turnover intention of the study subjects. The beta (β) coefficient from the general linear models, unadjusted score for job satisfaction with 95 percent Confidence Interval (CI) was β -0.318 (-0.399, -0.100); affective commitment was β -0.467 (-0.477, -0.215); continuance commitment was β 0.376 (0.153, 0.453); and normative commitment was β -0.198 (-0.309, -0.001). In the adjusted models the β value for Affective commitment -0.365 (-0.468, -0.072) and Continuance commitment was 0.432 (0.197, 0.500). The relationship was found statistically significant at p<0.05.

| Dimension of job satisfaction & organizational commitment | Unadjusted | Adjusted |

p-value |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ß | 95%CI | ß | 95%CI | ||

| Job satisfaction | -0.318 | -0.399, -0.100 | -0.181 | -0.301, 0.017 | 0.08 |

| Affective commitment | -0.467 | -0.477, -0.215 | -0.365 | -0.468, -0.072 | 0.008 |

| Continuance commitment | 0.376 | 0.153, 0.453 | 0.432 | 0.197, 0.500 | 0 |

| Normative commitment | -0.198 | -0.309, -0.001 | -0.015 | -0.217, 0.193 | 0.909 |

| Constant | 10.162 | 7.867, 12.458 | 0 | ||

Table 7: Unadjusted and adjusted linear regression coefficients for a mean score of employees’ turnover intention by job satisfaction and organizational commitment.

Discussion

Health workers are the most important building blocks of the health system [22] without which the other five building blocks, namely services; leadership and governance; finance; information; and supplies, technologies and pharmaceuticals could not achieve quality public health services for needy community members [24,25]. The aim of this research was to determine the magnitude of turnover and identify factors associated with turnover intention among health workers employed in PPM health facilities. Therefore, in this study, the direct effect of organizational commitment of employees of PPM facilities, job satisfaction and turnover intension was examined.

Close to two third of the research participants were aged less than 35 years. Almost half to the employees that participated in this research are female. However, the study found variability in gender participation as females were less represented than males (X2=11.045, p<0.001). The higher proportion of female employment might be explained by the higher number of female nurses which participated in this research, where private healthcare services demands caring, respectful and responsive behavior of health workers. Furthermore, an independent t-test was computed, and the researcher found statistically significant difference in mean score between males and females on measurements of overall organizational commitment and specifically in continuance commitment categories. Despite this, there was no statistical significant differences between males and females in terms of job satisfaction, turnover intention, affective and normative commitment domains. This finding was in line with Asegid et al. report no statistically significant difference between turnover intention by socio-demographic characteristics like age, sex, educational qualification benefit and salary [26].

In forty-five PPM surveyed health facilities, out of 474 employees, the magnitude of staff turnover was 24 percent. Moreover, slightly lower than half of the respondents (46%) want to leave their current job in the coming one year. This finding was consistent with the magnitude of turnover intention reported in Ethiopia, (50%) in Sidama [26]; and Gondar (52.5%) [27]. However, there was also a high magnitude of turnover intention reported (63.7%) in Jimma [28] and (59.4%) in East Gojjam zones [29]. These differences could be attributed with the differences in the target population. This study is concerned with public private mix health facilities, while the other studies focus on public health sector employees. Findings showed that unless the public and the private sector works together on retention mechanisms, the quality of initiated PPM for public health programs will be seriously affected [30].

Organizational commitment is defined as the individual ’ s psychological attachment to their organization. The basis behind many of these studies was to find ways to improve how workers feel about their jobs so that they would become more committed to their organizations. Organizational commitment predicts work variables such as turnover, organizational citizenship behavior, and job performance. Some of the factors such as role stress, empowerment, job insecurity and employability, and distribution of leadership have been shown to be connected to a worker's sense of organizational commitment that can cause employees to experience a 'sense of oneness' with their organization.

Job satisfaction has been explained as employees’ level of fondness for their job. Spector also explained that how people feel about the job to the extent of which people like or dislike their job and job satisfaction has a direct relationship with their health, productivity and attrition. In this study, slightly higher than half (54%) of the research participates were satisfied with their job. This finding was much lower than (63%) [22] of health workers which were satisfied in North Shoa zone of Ethiopia. Getahun et al. attests that the effect of job satisfaction varied form individual, organizational and social outcomes. On the one hand, the Person correlation test revealed a positive relationship between job satisfaction and organizational commitments [31]. On the other hand, job satisfaction has shown to have a negative correlation with health workers’ intention to quit their job. This finding was in agreement with Getahun et al. report as primary school teachers job satisfaction was positively correlated with organizational commitment [31]. Similarly, Bratton and Gold stated that jobs involving caring for people score highest in job satisfaction [32]. Form demographic variables gender (t (98)=-0.82, p=0.41) has no statistical difference in job satisfaction but it has a positive correlation with marital status and level of education. The result was not consistent with Getahun et al. [31] where they did find a significant correlation with the demographic variable.

In this study, the researcher found no statistical significant variation in turnover intention between males and females (p>0.05). However, employees with high score in affective commitment items will less likely have higher turnover intention. This finding was consistent with Chughtai and Zafar [33] documented in Pakistan among university teachers, that those who have more organizational commitment are less likely quit their job. Similarly, Jonathan et al. [34,35] in their study in Tanzania, revealed that teachers had low affective commitment, moderate continuance commitment, very low normative commitment and high intention to leave which may be executed into actual behavior next year. Higher score on organizational commitment dimensions had a significant negative relationship with intention to leave.

This research identifies factors associated with mean measurement difference of turnover intention with and between socio-demographic variables. There were statistically significant differences in average score of turnover intention by: age (p<0.05) in that younger age employees intend to leave their current employer than older age categories; single employees had a significantly more intention to turnover than married (p<0.05); and employs with lower education achievements were higher significantly in wanting to leave their current organization (p<0.05).

Limitations of the study

Due to time and financial constraints, the sample size was restricted to 100. In addition, private health facilities were selected with purposive sampling method.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Conclusion

One fourth of healthcare providers working in public private mix health facilities left their job within the previous year. In addition, almost half of currently employed healthcare providers had intension to turnover. After controlling the confounding variables, factors associated with intention to the turnover of health workers are directly related to organizational commitment. On the one hand, the higher organizational commitment with continuance commitment category staff will stay with their current employers. On the other hand, those with higher scores of organizational commitment on affective domain are prone to higher staff turnover. These findings clearly showed that only staff who felt working with the current employer is a matter of necessity will stay on at their job.

Recommendations

Based on the result of the study the following recommendations are forwarded to public and private health sectors and health workers.

Recommendation for the public health sector: To assure access and use of key public health services across the country and meet its national health goals, the FMOH in collaboration with all other stakeholders should work hard to deliver quality public health services, positive interventions that include support and coordination with private health facilities. It is clear that improving access to quality service for the community is the responsibility of the public health sector. Therefore, to ensure the sustainability and uninterrupted public health services through private sector, the public health sector should strive to improve the work environment of private sectors and closely work with private sectors on staff retention mechanisms.

Recommendation for the private health sector: The private health sector is regarded as having quality services as well as skilled and experienced staff. Therefore, the sector should fulfill the common interest among staff of creating motivation and long-term career development. Owners and managers are expected to build a functional team both in healthcare services and in personal relationships among staff. Efforts should reduce the turnover and considerable attention should be given to human resource development and staff benefits through revising promotion tools by evaluating the external market. The sector should give due emphasis to employee treatment, better payment and promotion mechanisms for better accomplishments and staff retention.

Recommendation for health workers: Health workers should take the lead in developing their careers by providing caring, respectful and companionate healthcare services. In this modern and competent world, professionals should update their knowledge with everchanging findings and developments in each field. As health-related scientific developments are enormous, professionals engaged in the health sector service must follow new updates and upgrade their capacity in order to deliver advanced services to clients and assist their supervisors by delivering the best service.

Declarations

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Public Private Mix health facilities, and Indra Gandhi National Open University for their support during the survey. We would like to thank all data collectors who invested their time and skill in collecting data in a professional manner. All respondents, managers of the health facilities deserve sincere appreciation for their participation in the study. The authors indebted to Heran Demisse for her English Language edition.

Funding

None. MDA, and BFD receive salary support for JSI Research & Training Institute, Inc.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors’ contribution

The authors of this manuscript are: WMD, WM, MDA, BFD, AYD.

All authors equally contributed the conception, designing of the study, fieldwork, data cleaning. Analysis and drafting the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final document. MDA: the corresponding author submitted the manuscript for publication.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The research protocol of was reviewed by Indra Gandhi National Open University Institutional Review Board (IRB) and research ethics committee. Oral consent was obtained from all research participants. The study had no known risk and no payment was made to participants.

References

- WHO (2006) The world health report 2006: working together for health. World Health Organization, Geneva.

- Atnafu K, Tiruneh G, Ejigu T (2013) Magnitude and associated factors of health professionals’ attrition from public health sectors in Bahir Dar city, Ethiopia. Health 5: 1109-1916.

- The Work Bank Group (2005) Ethiopia a Country Status Report on Health and Poverty. World Bank: Washington, DC.

- Ethiopian Federal Ministry of Health (2013) Public private partnership in Health: strategic framework for Ethiopia.

- Federal Ministry of Health (2012) Health and health related indicators of Ethiopia for the Year 2011/2012.

- Private Health Sector Program (2015) End of Project Report. Abt Associates Inc. Bethesda.

- Tsui KT, Cheng YC (1999) School organizational health and teacher commitment: a contingency study with multi-level analysis. Educational Research and Evaluation 5: 249-268.

- Hassi A, Storti G (2011) Organizational training across cultures: variations in practices and attitudes. Journal of European Industrial Training 35: 45-70.

- Dinham S, Scott C (1998) A three domain model of teacher and school executive career satisfaction. Journal of Educational Administration 36: 362-378.

- Brown D, Sargeant MA (2007) Job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and religious commitment of full-time university employees. Journal of Research on Christian Education 16: 211-241.

- Meyer J, Allen N, Gellatly I (1990) Affective and continuance commitment to the organization: Evaluation of concurrent and time-lagged relations. Journal of Applied Psychology 75: 710-720.

- Culibrk J, Delic M, Mitrovic S, Culibrk D (2012) Job Satisfaction, Organizational Commitment and Job Involvement: The Mediating Role of Job Involvement. Front Psychol.

- Lawrence A, Lawrence P (2009) Values congruence and organizational commitment: P-O fit in higher education institutions. Journal of Academic Ethics 7: 297-314.

- Maslow AH (1943) A Theory of Human Motivation. Psychological Review 50: 370-396.

- Fallatah RHM, Syed J (2018) A Critical Review of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. InEmployee Motivation in Saudi Arabia. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham.

- Geleto A, Baraki N, Atomsa GE, Dessie Y (2015) Job satisfaction and associated factors among health care providers at public health institutions in Harari region, eastern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study.BMC Res Notes8: 394.

- Ajayi K (2004) Leadership, Motivation, team work and information management for organizational efficiency. Niger J Soc Sci 74: 1-16.

- Campion MA (1991) Meaning and measurement of turnover: Comparison of alternative measures and recommendations for research. J Appl Psychol 76: 199-212.

- Brayfield AH, Rothe HF (1951) An Index of Job Satisfaction. J Appl Psychol 35(5), 307-311.

- Buchan J (2010) Reviewing the benefits of health workforce stability. Hum Resour Health 8: 29.

- Lance CE, Lautenschlager GT, Sloan CE, Varca PE (1989) A comparison between bottom-up, top-down and bi-directional models of relationships between global and life facet satisfaction. Journal of Personality 57: 601-624.

- Ferede A, Kibret GD, Million Y, Simeneh MM, Belay YA, et al. (2018) Magnitude of Turnover Intention and Associated Factors among Health Professionals Working in Public Health Institutions of North Shoa Zone, Amhara Region, Ethiopia.Bio Med Research International.

- Hales LD (1986) Training: a product of business planning. Training & Development Journal 40: 65-66.

- Naseem BY, Khan I, Khan F, Khan H, Nawaz A, et al. (2013) Determining the demographic impacts on the organisational commitment of academicians in the HEIs of DCs like Pakistan. European Journal of Sustainable Development 2: 117-130.

- World Health Organization (2007) Everybody's business--strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes: WHO's framework for action.

- Asegid A, Belachew T, Yimam E (2014) Factors influencing job satisfaction and anticipated turnover among nurses in Sidama zone public health facilities, South Ethiopia.Nursing Research and Practice.

- Abera E, Yitayal M, Gebreslassie M (2014) Turnover Intention and Associated Factors Among Health Professionals in University of Gondar Referral Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. Int J Econ Manag Sci 3: 196.

- Kalifa T, Ololo S, Tafese F (2016) Intention to leave and associated factors among health professionals in jimma zone public health centers, Southwest Ethiopia.Open Journal of Preventive Medicine6: 31-41.

- Getie GA, Betre ET, Hareri HA (2015) Assessment of factors affecting turnover intention among nurses working at governmental health care institutions in East Gojjam, Amhara Region, Ethiopia, 2013.American Journal of Nursing Science4: 107-112.

- Spector PE (1997)Job satisfaction: Application, assessment, causes, and consequences. Sage publications.

- Getahun T, Tefera BF, Burichew AH (2016) Teacher’s Job Satisfaction and Its Relationship with Organizational Commitment In Ethiopian Primary Schools: Focus On Primary Schools Of Bonga Town. European Scientific Journal 12: 380- 401.

- Bratton J, Gold J (1999)Human resource management: theory and practice. Macmillan.

- Chughtai AA, Zafar S (2006) Antecedents and consequences of organizational commitment among Pakistani university teachers. Applied H.R.M. Research 11: 39-64.

- Jonathan H, Thibeli M, Darroux C (2013) Impact investigation of organizational commitment on intention to leave of public secondary school teachers in Tanzania. Developing Country Studies 3: 78-91.

Citation: Dado WM, Mekonnen W, Aragw MD, Desta BF, Desal AY (2019) Turnover Intention of Health Workers in Public-Private Mix Partnership Health Facilities: A Case of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia . Epidemiology (Sunnyvale) 9:374. DOI: 10.4172/2161-1165.1000374

Copyright: © 2019 Dado WM, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 4451

- [From(publication date): 0-2019 - Dec 20, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 3543

- PDF downloads: 908