Vascular Anatomy of Little's Area in Children with Epistaxis

Received: 16-May-2013 / Accepted Date: 25-Jul-2013 / Published Date: 01-Aug-2013 DOI: 10.4172/2161-119X.1000136

Abstract

Epistaxis in children in more than 90% of the cases from the anterior nasal cavity. In the majority of the paediatric population Epistaxis is due to trauma (accidents, manipulation, secondary hemorrhages after surgery), bleeding disorders (v.-Willebrand´s disease, side-effects of medication), dry climate (low humidity, heating period), rhinitis, vascular abnormities and rarely it is due to hereditary syndromes. In contrast to Epistaxis in adults, blood pressure changes play no essential role in paediatric nosebleeds. The present publication analyses the vascular anatomy of the anterior nasal septum (Little´s area) based on video endoscopic findings in affected children. Video endoscopies of 16 children could be analysed for the study. Twelve of 16 children had a prominent vessel shining through the mucosa at the anterior or lower edge of the nasal septum and teleangiectic vessels appeared in 4/16 cases. The endoscopic examinations showed that the dominant vessels for the anterior septum were emerging from the floor of the nose, making a 90° cranial direction turn towards Little’s area. In contrast to most descriptions in literature, anastomoses with vessels coming from the cranial parts of the nose, deriving from the anterior ethmoidal artery, could not be found. According to the findings of the present analysis, Little’s area therefore is predominantely supplied by the septal branch of the superior labial artery and inferior septal branches of the sphenopalatine artery. Results in Epistaxis therapy might be improved, if the respective terminal branches of these vessels can be obliterated succesfully.

Keywords: Epistaxis, Telangiectases, Videoendoscopies

253825Introduction

Epistaxis is a frequent event among children. About 9% of all children and teenagers suffer from nosebleeds during their childhood or adolescene [1]. Peak incidences can be found in the age range between 2 and 11 years [2]. Boys are more often affected than girls, the male:female ratio ranges from 1.15-1.4:1 [3,4]. Despite sufficient therapy 28% of the paediatric nosebleed patients suffer from recurrent bleeding [5]. This observation prompted us to initiate this investigation to learn more about the vascular anatomy of the nose. A targeted therapy of the responsible vessels might then help to improve the results.

Patients and Methods

Patient´s inclusion criteria were the following: recurrent Epistaxis as chief complaint, paediatric age group, complete medical history, recorded video endoscopy. The exclusion criteria were: evidence of systemic disease (e.g. haematologic disorder, coagulation disorder), history of prior surgery on the nasal septum and history of recent nasal trauma.

Sixteen children and adolescents in an age range of 4 months-16 years could be identified, where the vascular anatomy of the nose had been documented by video endoscopy. Video endoscopy had been performed prior to Nd:YAG laser therapy for recurrent Epistaxis. In the initial examination the nose was assessed by anterior rhinoscopy after decongestion of the nose (Xylometazolin, 0.05%) to identify the source of bleeding. A detachable video camera (Endovision Telecam, Karl Storz Co., Tuttlingen, Germany) was mounted to a 0°-degree endoscope (Hopkins Rod Lense, Karl Storz Co., Tuttlingen, Germany) and digital images of the anterior nasal cavity were shot and stored on the AIDA system (Karl Storz Co., Tuttlingen, Germany). The images were then analysed for any pathologic findings (prominent vessels, telangiectasies, signs of inflammation, septal deviations, foreign bodies, turbinate pathology, polyps etc.). Findings were correlated with the clinical recordings to allow a better characterisation of Epistaxis (frequency, duration, intensity, blood pressure, risk factors, and medication).

Results

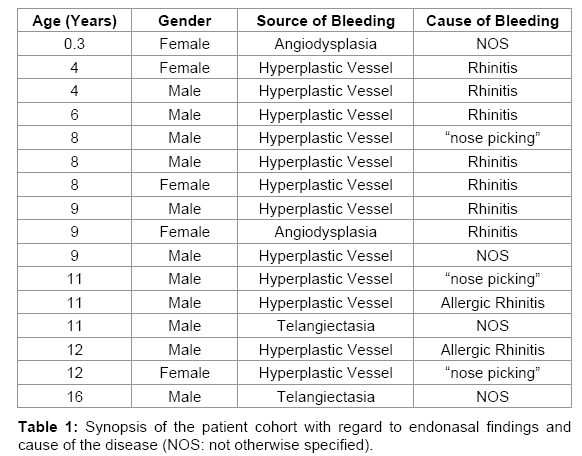

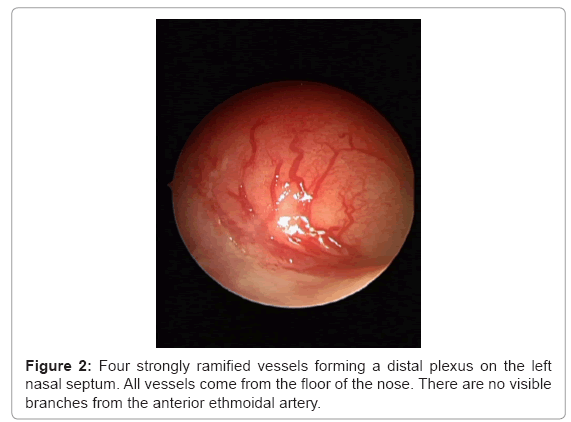

Video endoscopies and patients charts of 16 children in an age rage between 0.3-16 years (mean value: 8.9 years) were analysed for this investigation. The patient group consisted of 11 boys (68.7%) and 5 girls (31.3%). All 16 patients showed vascular pathologies on Little´s area, prominent vascular trees were evident in 12 cases and vascular malformations were observed in 4 cases. Thus the patients could be divided into two groups. The first group showed hyperplastic vessels with a clearly identifiable stem and branches (12 patients). The second group exhibited vascular malformations on the nasal septum (telangiectasia: 2 patients; angiodysplasia: 2 patients). Hypertonic or hypotonic blood pressure levels were noted only during emergency treatments as a transient phenomenon, all control measurements in follow-up showed normal blood pressure levels. Six children had been treated with non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs prior to the bleeding event and 5 children admitted to have used decongestant nosedrops before the bleeding had started. Seven patients suffered nosebleeds secondary to “common cold”–rhinitis, three patients admitted to bleedings secondary to nose picking. Allergic rhinitis was evident in 2 children. Four children suffered nosebleeds for no specific reasons (Table 1). Patients were seen for follow-up on 2nd post-op day, 14 days post-op and 3 months post-op.

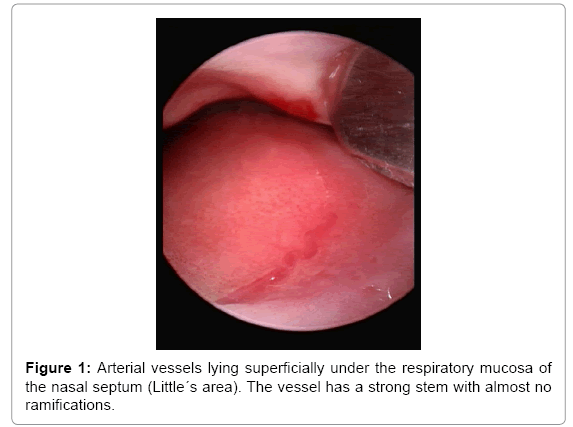

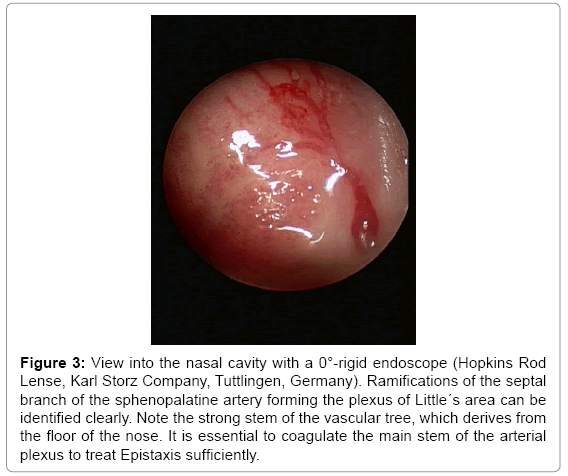

The shape of the vascular tree varied from a single main stem with only a few branches (Figure 1) to several stems with multipe branches (Figure 2). A uniform finding however was all vessels derived from the floor of the nose or the caudal septum (Figure 3). The main stem could be identified as the vessel with the strongest diameter. The vessel with the strongest diameter was always in the caudal zone of the septum, the branches were decreasing in diameter in cranial direction until they faded from the macroscopically identifiable size into the capillary size. Anastomoses with vessels deriving from the cranial area of the nose (i.e. the anterior ethmoidal artery) were not observed. According to these findings Little´s area is basically supplied by the septal branch of the superior labial artery and the inferior septal ramus of the sphenopalatine artery.

Figure 3: View into the nasal cavity with a 0°-rigid endoscope (Hopkins Rod Lense, Karl Storz Company, Tuttlingen, Germany). Ramifications of the septal branch of the sphenopalatine artery forming the plexus of Little´s area can be identified clearly. Note the strong stem of the vascular tree, which derives from the floor of the nose. It is essential to coagulate the main stem of the arterial plexus to treat Epistaxis sufficiently.

There was no correlation between frequency of hemorraghes and the finding “prominent vessel”. Patients with telangiectases on the other hand had weekly, sometimes daily periods of bleeding. Intensity of hemorrhages was increased in patients with prominent vessels, patients reported on bleeding episodes, which lasted for one hour and even longer. Half of the patients had bilateral bleedings, but one side tended to bleed more often. The only significant secondary findings were signs of rhinitis and crusting in 1/3 of the cases. Patients were treated by Nd:YAG laser therapy (8-12 W, cw-mode, 600 μm fiber) under microscopic control in general anaesthesia. The branches of the vascular tree were photocoagulated until a blanching effect could be noted. Postoperatively the nasal mucosa was treated with lubricants. Half of the patients were free of symptoms after one session, 1/3 reported persistent bleedings on the side of the septum, which had not been treated. In all cases intensity and frequency of bleedings was sigificantly reduced. No further bleedings lasting longer than 10 minutes were observed. One third of the patients requested repeated therapy, in the respective cases the stem of the remaining vessels was coagulated by bipolar cautery. No further hemorrhages were evident after this treatment. No undesired side effects apart from delayed wound healing, local irritations and crusting were observed. All problems resolved under intensified local care with lubricants.

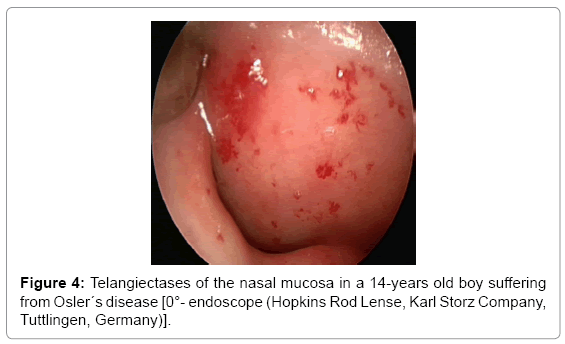

Four patients suffered from dysplastic vessels within the mucosa on the anterior nasal septum. In two of these cases Rendu-Osler-Weber- Syndroms was diagnosed according to the criteria of the Scientific Advisory Board of the HHT Foundation International (positive family history, recurrent Epistaxis, telangiectases, visceral arteriovenous malformations). Interestingly these patients showed multiple telangiectases (Figure 4), but no main vascular stem, which could be identified as the feeding vessel. Therapy was similar to the cases mentioned above, but all patients needed bilateral therapy, which was performed after a three month interval. The Osler patients were treated as inpatients and a comprehensive screening for visceral arteriovenous vascular malformations was performed. These visceral vascular malformations can be found in more than 1/3 of all Osler patients and some can be treated preventively. Luckily screening detected no hidden vascular malformations. Treatment results were very encouraging; both patients had no significant bleeding after 26 months follow-up, results which are clearly superior to laser therapy in adult Osler patients. The two remaining patients with nasal telangiectases did not qualify for the diagnosis of Osler´s disease. Nosebleeds however could be stopped successfully by laser therapy and nasal lubrication.

Discussion

In more than 90% of the cases paediatric Epistaxis derives from the anterior nasal cavity [6]. The combination of superficially situated vessels on Little´s area with rhinitis, a dry climate and eventually nose picking can cause impressive nose bleeds [5]. Clotting disorders like v.-Willebrands disease may also play a part in paediatric Epistaxis, the incidences vary between 12-30% of the respective investigated groups [5,7]. Vascular anatomy however plays the key role in paediatric Epistaxis. Textbooks and scientific publications generally describe the anatomy of Little´s area as a vascular network, which is formed by vessels deriving from the sphenopalatine artery, the superior labial artery and vessels from the anterior ethmoid artery [8]. The present investigation gave some new insights into this field. On videoendoscopy only vessels on the caudal septum could be seen regularly. Septal branches of the superior labial artery and the sphenopalatine artery are the main feeding vessels; clinically there are no significant contributions of the anterior ethmoidal arteries evident.

The vessels at Little´s area have been noted by others but, to the best of our knowledge, a video endoscopic study has not been performed before. Most studies on the vascular anatomy of the nose have either been performed by Anatomists or by Radiologists [6-10]. In anatomic studies bodies of donors are usually dissected. Body donors are usually senior adults. Vascular anatomy is subject to changes during life. An explanation for our observation of missing feeding branches from the anterior ethmoidal arteries in a paediatric patient group could be explained by the fact, that these vessels develop later in life, or that they might remain dormant in childhood and youth and only become clinically identifiable later in life. Methodical problems might also help to explain our findings. In anatomic studies major arteries of the body are usually injected with dyed gelatinous substances or synthetic material. Sometimes contrast media are added [8]. The vascular trees can then be studied either radiologically or by anatomic dissection [8,10]. Peripheral and very thin vessels can rarely be visualized satisfactorily by these methods unless the feeding vessels have been punctured and injected superselectively. This may explain why the vessels of the Kiesselbach plexus can hardly be visualized by general injection studies. Histological sectioning of the respective anatomical region on the other hand gives good information on vessel diameters and the structure of the vessel walls, but it is a poor technique to give a survey of the architecture of a vessel [11]. These facts may explain the discrepancies between the findings of our study and the depiction of Little´s area in the textbooks. Radiologic studies also either rely on angiographies or on CT scanning [10]. Both techniques give little information on peripheral vessels of almost capillary diameter unless the respective areas are studied selectively. Studies on general angiographies of the head might therefore give little information on the septal branches of the superior labial artery, if it is not injected selectively. Video endoscopy on the other hand is an “in vivo”-method, which allows to investigate the pathologic anatomy in a living patient and to analyse the findings later in the media lab.

Johansson et al. investigated these vessels histologically and macroscopically [12]. According to Johansson the wall of the respective vessels is very thin and consists mostly of endothelium with no sufficient muscular insulation. Once the vessel bursts it is not capable to contract and stop the bleeding by vascular hemostasis. This observation is consistent with the finding of the present study, which showed that bleeding episodes from prominent vessels at Little´s area were characterised by prolongued hemorrhage. Epistaxis with more than one hour of duration is possible. Longlasting and intense nasal bleedings are often the main cause for the children and their parents to seek medical advice. The characteristics of nasal hemorrhages in children with endonasal telangiectases are different. Bleeding episodes are more frequent, sometimes the children suffer from Epistaxis every day. Frequency of Epistaxis is high but the duration of bleeding rarely exceeds 20 minutes. Basically telangiectases are a rather rare finding and they are almost pathognomonic for Osler´s disease. M. Rendu- Osler-Weber (M. ROW), also known as Hereditary Hemorrhagic Teleangiectasia (HHT), is a disease which is inherited in an autosomaldominant trait. For many years it was thought that recurrent Epistaxis, the key symptom in HHT, manifests itself after puberty [13]. Recent investigations showed that recurrent Epistaxis in HHT occurs already in childhood in 2/3 of the cases [14]. HHT-related Epistaxis has different characteristics than uncomplicated paediatric Epistaxis. It is of special significance because it is the index symptom of the disease, which can help to make the diagnosis at an early age, based on clinical criteria. It is beyond the scope of this communication to discuss HHTrelated Epistaxis. The implication of HHT-related Epistaxis in children and adolescents is that of a warning sign. It offers the chance to perform a screening for visceral arteriovenous malformations in the affected children before they become symptomatic. In some cases this offers the chance to treat the vascular malformations before they cause any health problems [15]. Interestingly it seems that children with HHT respond better to endoscopically guided laser therapy of nasal telangiectases than adults [14].

Therapy of paediatric Epistaxis should start with conservative treatment. London and Lindsey were able to successfully treat 89% of their patients by simply prescribing lubricants [16]. Lubrication of the nose with ointments is a convincing therapy, not only in children. Apart from potentially unpleasant odours there are hardly any side-effects of this therapy, thus the compliance in children is high [17]. More invasive forms of therapy are coagulation and occlusion of bleeding vessels [18,19]. Link et al. favour chemical cautery with silver nitrate, which is reported to have a 93% success rate [20]. In the present study Nd:YAG laser therapy and bipolar cautery was used [21]. In the authors point of view targeted therapy under microscopic or endoscopic controls allows selective therapy of pathologic vessels with the least damage to surrounding tissues. This goal is difficult to achieve by chemical cautery. If necessary, stronger vessels can be cauterised with a bipolar forceps in addition to laser therapy. In every case it is essential to keep the collateral thermal damage to the mucosa as minimal as possible. The strategy was very efficient, by Nd:YAG laser therapy combined with targeted bipolar cautery all bleedings could be stopped, if the main stem of the feeding vessels was occluded at the floor of the nose. A disadvantage is, of course, the fact that this therapy should be administered in general anaesthesia, a child should be at least seven years of age, if the procedure should be performed in local anaesthesia.

Conclusion

Paediatric Epistaxis originates in more than 90% of the cases in the anterior nasal cavity, almost exclusively from Little’s area. Through the analysis of videoendoscopies it could be shown that the vascular anatomy of the anterior nasal septum is different from most of the descriptions, which have been published in the scientific literature so far. Feeding arteries of the respective vascular plexus derive from the septal branch of the superior labial artery and the inferior septal branches of the sphenopalatine artery. There were no visible branches from the anterior ethmoidal artery in paediatric patients.

References

- Rodeghiero P, Castaman G, Dini E (1987) Epidemiological investigation of the prevalence of Von Willebrand’s disease. Blood 69: 454-459

- Culbertson MC, Manning S (1990) Epistaxis, in: Paediatric Otolaryngology 2nd ed., Bluestone/Stool, Philadelphia, London, Toronto, Mexico City, Rio de Janeiro, Sydney, Tokyo.

- Sandoval C, Dong S, Visintainer P, Ozkaynak MF, Jayabose S (2002) Clinical and laboratory features of 178 children with recurrent epistaxis, J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 24: 47-49

- Kubba H, MacAndie C, Botma M, Robison J, O'Donnell M, et al. (2001) A prospective, single-blind, randomized controlled trial of antiseptic cream for recurrent epistaxis in childhood, Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci, 26: 465-468

- Kiley V, Stuart JJ, Johnson CA (1982) Coagulation studies in children with isolated recurrent epistaxis. J Pediatr 100: 579-581

- Tillmann B (1997) Farbatlas der Anatomie. 1st. Ed Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart.

- Koh E, Frazzini VI, Kagetsu NJ (2000) Epistaxis-Vascular Anatomy, Origins and Endovascular Treatment. AJR Am J Roentgenology 174: 845-851

- Grevers G, Heinzmann U (1988) Scanning electron microscopic studies oft he nasal blood vessels. Arch Otorhinolaryngol 244: 363-366

- Johansson BR, Beran M, Petrusson B (1985) Light and electron microscopy of varicose vessels and telangiomas in the nasal mucosa of habitual nosebleeders. Acta Otolaryngol 99: 620-629

- Plauchu H, de Chadarevian JP, Bideau A, Robert JM (1989) Age-related clinical profile of hereditary hemorrhagic teleangiectasia in an epidemiologically recruited population. Am J Med Genet 32: 291-297

- Folz BJ, Zoll B, Alfke H, Toussaint A, Maier RF, et al. (2006) Manifestations of hereditary hemorrhagic teleangiectasia in children and adolescents. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 263: 53-61

- Folz BJ, Wollstein AC, Alfke H, Dünne AA, Lippert BM, (2004) The value of screening for multiple arterio-venous malformations in hereditary hemorrhagic teleangiectasia: A diagnostic study. Eur Arch Otolaryngol 261: 509-516

- London SD, Lindsey WH (1999) A reliable medical treatment for recurrent mild anterior epistaxis. Laryngoscope 109: 1535-1537

- Ruddy J, Proops DW, Pearman K, Ruddy H (1991) Managment of epistaxis in children, Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 21: 139-142

- Padgham N (1990) Epistaxis: anatomical and clinical correlates. J Laryngol Otol 104: 308-311.

- Toner JG, Walby AP (1990) Comparison of electro and chemical cautery in the treatment of anterior epistaxis. J Laryngol Otol 104: 617-618

- Link TR, Conley SF, Flanary V, Kerschner JE (2006) Bilateral epistaxis in children: efficacy of bilateral septal cauterization with silver nitrate, Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 70: 1439-1442.

- Werner JA, Rudert H (1992) Der Einsatz des Nd:YAG-Lasers in der Hals-, Nasen-, Ohrenheilkunde HNO, 40: 248-258

Citation: Folz BJ, Harlfinger M, Werner JA (2013) Vascular Anatomy of Little´s Area in Children with Epistaxis. Otolaryngology 3:136. DOI: 10.4172/2161-119X.1000136

Copyright: © 2013 Folz BJ, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 23285

- [From(publication date): 9-2013 - Dec 22, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 18359

- PDF downloads: 4926