A Descriptive Study to Assess Compassion Fatigue among Caregivers of Patients Undergoing Chemotherapy in Selected Tertiary Care Centre

DOI: 10.4172/1522-4821.1000483

Abstract

Diagnosis of cancer almost always creates a situation of crisis for patients and their families. Patients and their loved ones experiences variable degree of fear and anxiety while going through process of cancer treatment. Moreover cancer management involves variety of treatment modalities each of which takes considerable time duration. In such times, family becomes integral part of patient’s support system. Even though the term ‘compassion fatigue used mainly for health care professional but family members may also experience the similar stress while dealing with patient’s diagnosis and it’s long term treatment. Because of minimal knowledge and uncertainty of treatment outcome family members may face tough decision making situations which can be traumatic for them and may result into burn out. Objectives: The study was aimed at assessing the level of compassion fatigue among family caregivers of patients undergoing chemotherapy. The study also had secondary objective of associating the level of compassion fatigue with selected demographic variables. Methods: Exploratory descriptive design was used in study. 80 family care givers were included with non-probability convenience sampling at chemotherapy unit of tertiary care hospital. Data related to compassion fatigue was collected from family care takers of patients visiting for chemotherapy cycles with 27 point rating scale. Results: Mean compassion satisfaction and mean compassion fatigue was 41.16 and 52.35 respectively. Majority of caregivers 41 (51.2%) had average satisfaction level while 39 (48.8%) had high satisfaction level. In case of assessment of level of compassion fatigue, majority of participants 74 (92.5%) had high compassion fatigue and only 6 (7.5%) had moderate compassion fatigue. None of participant reported low compassion fatigue as well as low compassion satisfaction. Monthly income is found significantly associated with level of compassion satisfaction whereas relation with patient found significantly associated with level of compassion fatigue among care givers. Other socio-demographic variables like age, gender, education, occupation & period of care giving are not significantly associated with compassion satisfaction or compassion fatigue. Compassion fatigue and compassion satisfaction is significantly correlated and is inversely proportionate to each other. Conclusion: As a result of increased outpatient services & shorter hospital stay supportive home care has become integral part of patient’s management. Moreover due to improved survival rates and quality of life for cancer patient families have started becoming accommodative towards this trend. But sometimes family member assume role of caregiver under sudden and extreme circumstances. Caring for a family member with cancer can be physically and emotionally very challenging. The findings of the study suggest that compassion fatigue is extremely common experience among caregivers of patient undergoing chemotherapy. Family caregivers being patient’s essential partners in the delivery of complex health care services, their mental health needs should recognised and effective strategies should be planned by health care workers to help them deal with stressful situations.

Keywords: Compassion Fatigue, Chemotherapy, Family Caregiver

Introduction

Harris and Griffin (2015) defined compassion fatigue (CF) as “physical, emotional, and spiritual result of chronic selfsacrifice and/or prolonged exposure to difficult situations that renders a person unable to love, nurture, care for, or empathize with another’s suffering” (Harris & Griffin, 2015). Compassion fatigue, also known as secondary traumatic stress, it is a condition characterized by a gradual lessening of compassion over time (Coroner talk). The term compassion fatigue (CF) was coined to described the phenomenon of stress resulting from exposure to a traumatized individual rather than from exposure to the trauma itself (Figley, 1995). CF is characterized by exhaustion, anger and irritability, negative coping behaviours including alcohol and drug abuse, reduced ability to feel sympathy and empathy, a diminished sense of enjoyment or satisfaction with work, increased absenteeism, and an impaired ability to make decisions and care for patients and/or clients (Mathieu, 2007). This can have detrimental effects on individuals, both professionally and personally, including a decrease in productivity, the inability to focus, and the development of new feelings of incompetency and self-doubt. This selfdoubt can cause problems at work and home, and over time will affect all relationships (Coroner talk).

The term ‘compassion fatigue’ is predominantly used with professional caregivers, such as nurses, doctors and social workers. But it can be seen among any individuals that work directly with trauma victims or constantly deal with people who are in state of crisis (Lynch, & Lobo, 2012). Family caregivers of patients suffering from chronic diseases like cancer is one of the vulnerable group to develop compassion fatigue over period of time especially due to nature of disease & treatment duration and longer survival of patients. The terms family caregiver and informal caregiver refer to an unpaid family member, friend, or neighbour who provides care to an individual who has an acute or chronic condition and needs assistance to manage a variety of tasks, from bathing, dressing, and taking medications to tube feeding and ventilator care (Reinhard et al., 2008).

Participation of family members has become integral part of home care management of chronic disease like cancer. The diagnosis of cancer not only affects individual patient but also affects the lives of other family members, bringing an immense amount of stress and many challenging situations (Woźniak et al., 2014). Due to advancement of treatment strategies, emphasis has increased on use of outpatient care & minimum hospital stay. There is increasing trend of patients opting for home based care in order to stay in familiar environment. It may lead to significant change in daily routine, common activities and distribution of duties of family members. This sudden change may present as crisis to not only patients but their family members. More over most of the families are minimally prepared to face such situations and are prone to develop compassion fatigue over a period of time (Woźniak et al., 2014; Glajchen, 2004). Family care giving has gained attention in the past decade with growing realization that support for family caregivers benefits the caregiver, the patient, and the healthcare team. Even though family involvement is beneficial to patients and as to health care workers, it has brought them closer to stress associated with various treatment strategies and their uncertainty (Glajchen, 2004).

Cancer diagnosis often creates an urgency to start the treatment and even when patients and families receive education, they still might feel unprepared. Chemotherapy forces the patient and family to adhere to schedules of medical appointments or hospitalizations and to reallocate family roles because the patient usually cannot meet obligations because of fatigue or other side effects. Seeing the patient going through pain and discomfort can create distress in family members. Fatigue and irritability experienced by the patient and family can increase the negative impact on the family system (Gorman, 1998). Care givers burnout happens when there is prolong state of stress or distress, which may result in feeling of tension, anger, anxiety, depression irritability, frustration and fearfulness. Family caregivers are expected to provide complex care in the home with little preparation or support. When the demands placed on caregivers exceed their resources, caregivers feel overwhelmed and report high stress. The stress has a negative effect initially on the caregiver’s psychological as well physical well-being (Day & Anderson, 2011). It’s important to stress that the people who care the most are the one who are at risk of compassion fatigue. Secondary stress is the byproduct of being empathetic and caring. The term burn out is more familiar than compassion fatigue. Burnout tends to develop gradually over time and, though a caregiver may feel exhausted, he or she continues to feel empathy and a desire to care for their loved one. In contrast, compassion fatigue often develops suddenly, though most often after a period of burnout. A caregiver who was previously very empathic and caring may feel a lack of empathy or even indifference when it comes to caring for their loved one or patient with cancer (Lynne, 2019).

Need of the Study

Compassion fatigue was introduced to the health care community as a unique form of burnout experienced by those in caring professions, particularly palliative care and oncology nurses (Joinson, 1992). Later, other health care professions such as social work, medicine, and psychology adopted the concept (Figley, 2002; McHolm, 2006; Sabo, 2006). Thus compassion fatigue is well recognized mental health issue for those who work with cancer patients. Burton et al examined the relationships between provision of care by family members and their health behaviors and health maintenance. It was found that family caregivers have high chance of getting inadequate rest, inadequate time for exercise and also may forget to take their own prescription drugs. If caregivers are to continue to be able to provide care, relief from the distress and demands of maintaining the required care must be considered (Burton et al., 1997). Patient is always remain central health care services and caregivers get very little help from health care professionals in managing their tasks and the emotional demands of care giving (Levine, 1998). Even though the importance of care givers role in patient’s recovery is well recognized, health professionals’ invariably fails to give attention to caregivers and their potential problems. Caregivers are hidden patients themselves, with serious adverse physical and mental health consequences from their physically and emotionally demanding work as caregivers and reduced attention to their own health and health care (Schumacher et al., 2008). Caregivers who try to manage their own life activities and responsibilities along with care giving may still feel sense of burden occasionally (Pavalko & Woodbury, 2000; Schumacher et al., 1993; Stephens et al., 2001). Distress may arise from getting involved in high level of care giving but it ,may also be experienced when not been able to engaging valued care giving activities (Cameron et al., 2002). Caregivers who are employed may find it difficult to adapt employment obligations along with role of caregiver. This may affect their financial and professional aspect of life. (Neal et al., 1993) Sometimes work may also act as buffer to stress as they get respite from care give activities (Pinquart & Sörensen, 2003). Clark et al in their study on cancer caregiver fatigue found that caregivers of patients with advanced stage cancer undergoing radiotherapy reported experiencing significant difficulties with fatigue (Clark et al., 2014). During the process of care giving for cancer patients, relatives are affected physiologically, psychologically and socially. They tend to hide their feelings for fear that it might upset patient. They also faced difficulty dealing with patient’s reactions during the treatment process (Serçekuş et al., 2014). Chemotherapy is a treatment strategy which goes on for weeks to months. And majority time patient needs to visit hospital for receiving chemotherapy which may take few hours to full day. Care takers almost always have to accompany the patients which can be become inconvenient to him/her over a period of time. Moreover chemotherapy is associated with variety of acute and late onset side effects which are generally managed at home. Family caregivers, thus has a huge responsibility of patient home management which may result in mental and physical stress.

Issues discussed in the area of psychological health of caregivers include anxiety, worry, burden, depression, and anger. Most of the literature is on anxiety, depression, and burden. Descriptions are beginning to mention compassion fatigue and post-traumatic stress as psychological health concerns for caregivers; especially caregivers of hospice patients (Fletcher et al., 2009). A large number of patients with chronic diseases like, cancer are cared for in homes by the family members in India. The vital role that these family members play as “caregivers” is well recognized; however, the burden on them is poorly understood (Lukhmana et al., 2015).

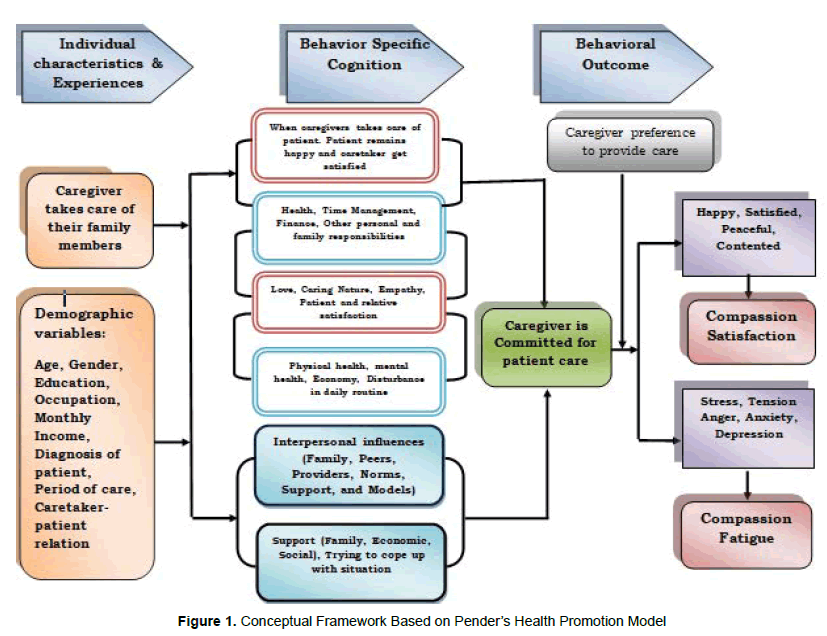

Conceptual Framework

The health promotion model proposed by Nola J Pender (1982; revised, in 1996) was used for this research study (Figure 1). The health promotion model describes the multi-dimensional nature of persons as they interact within their environment to pursue health. The model assumes that the individuals seek to actively regulate their own behaviour. Individuals in all their bio psychosocial complexity interact with the environment, progressively transforming the environment and being transformed over time. This model is chosen for family care giver in this study because it focuses on individual characteristic and experiences, behaviour specific cognition and their affect and behaviour outcome.

Methods

80 family caregivers who accompanied the cancer patients to chemotherapy unit were selected from of Nov 2019 to Jan 2019. They were screened for eligibility to participate in the study with help of inclusion criteria. All family caregivers who fulfilled the following inclusion criteria were invited to participate in study:

Inclusion criteria:

1. Aged 18 and above

2. Primary caregiver of patients undergoing chemotherapy.

3. Caregivers of patients who accompanied patients to chemotherapy unit

4. Caregivers of patients who have completed minimum 3 cycles of chemotherapy

1. Exclusion criteria:

1. Caregivers who are not willing to participate in the study.

2. Caregivers who occasionally involved in patients care.

3. Care takers of in house patients visiting chemotherapy unit

Instrument

Data was collected with help of structured questionnaire to assess demographic variables and rating scale to measure level of compassion fatigue

1. SECTION A: Demographic data of caregivers of patients undergoing chemotherapy. It contained total of 6 items: age, sex, education, monthly income, relation with patient & period of care giving.

2. SECTION B: Rating scale to assess compassion fatigue. Rating scale consisted total of 27 items out of which 13 items were for assessing compassion satisfaction and 14 items were for assessing compassion fatigue. Each items had five opinions i.e. Never, Rarely, Sometimes, Often, Very often. The maximum score of response for compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue were 63 and 58 respectively.

Validity of the rating scale was established in consultation with experts. It was validated by 11 experts in the field of nursing, oncology and statistics. The experts consisted of 9 nursing personnel, 1 Oncologist and 1 statistician. To assess compassion fatigue among caregivers the score of rating scale is grouped into categories like low, average, and high according to tertile range method. The cronbach Alpha test was used to assess the reliability of tool. The reliability of the tool is 0.76 which confirmed the reliability of the tool.

Data Collection

Prior to collection of data, permission was obtained from concern authority of selected tertiary hospital. The data collection process began from 03-11-2019 to 24-02-2020. Each subject was explained about the study and its purpose. Subjects who agreed to join the study were given self structured questionnaire to collect their demographic data and rating scale was used to collect data for measurement of compassion satisfaction & compassion fatigue. They were given adequate time to fill up the data sheet and queries were solved if there was any.

Data Analysis

Statistical package for the social sciences version 17.0 version for windows developed by IBM Corporation was used in data analysis in this study. The ANOVA test & Mann-Whitney test was used to correlate the compassion fatigue and compassion satisfaction with demographic variables. A probability value of 0.05 was accepted as the level of statistical significance. The level of statistical significance for this study was set at 95%

Ethics

1. The proposal of the study was presented to Institutional Ethical Committee. The study commenced after the approval of the said committee.

2. Permission from the concerned authority of the selected hospital was taken

3. Confidentiality of the records is maintained by the researcher. Anonymity was ensured on the instrument

4. Informed consent was taken from the subjects.

5. Subjects were protected from all types of harm.

Results

Section I: Family Caregiver’s Demographics

Table 1: Majority of participants were from age group of 40-49 (37.5%) & 30-39 (32.5%). Majority of the caregivers 42 (52.5%) were males. 34 (42.5%) of participants had higher secondary education & 27 (33.8%) were graduates. 50 (62.5%) caregivers were salaried, with 31 (38.8%) of participants having monthly income between15000-50,000. Majority 34 (42.5%) of caregivers were providing care from 6 months and majority of them were either spouse (36.3%) or children (30%) of patient. As per diagnosis of participants, majority cases were lung cancer (15%), breast cancer (12.5%), oral cancer (12.5%) and others cases were of ca. Stomach, ca. Larynx, ca. Rectum, ca. Tongue, ca. Uterus, leukaemia, ca. Cervix, and ca. Ovary.

| Parameters | No of cases | Percentage (n=80) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Yrs) | 21 – 30 | 16 | 20.0 |

| 31 – 40 | 28 | 35.0 | |

| 41 – 50 | 25 | 31.3 | |

| >50 | 11 | 13.8 | |

| Gender | Male | 42 | 52.5 |

| Female | 38 | 47.5 | |

| Educational status | Illiterate | 3 | 3.8 |

| Primary | 3 | 3.8 | |

| Secondary | 13 | 16.3 | |

| Higher secondary | 34 | 42.5 | |

| Graduate/ PG | 27 | 33.8 | |

| Occupation | Retired | 2 | 2.5 |

| Business | 12 | 15.0 | |

| Salaried | 50 | 62.5 | |

| House maker | 16 | 20.0 | |

| Monthly income (Rs) | No | 19 | 23.8 |

| <15000 | 26 | 32.5 | |

| 15000 – 50000 | 31 | 38.8 | |

| >50000 | 4 | 5.0 | |

| Period of care giving | From 3 months | 19 | 23.8 |

| From 6 months | 34 | 42.5 | |

| From 10 months | 18 | 22.5 | |

| More than 1 year | 9 | 11.3 | |

| Relation with patient | Spouse | 29 | 36.3 |

| Parent | 6 | 7.5 | |

| Child | 24 | 30.0 | |

| Others | 21 | 26.3 |

Table 1 Socio-demographic data of the participants (original)

Section II: Assessment of the Compassion Satisfaction and Compassion Fatigue

(Table 2) Mean compassion satisfaction and mean compassion fatigue was 41.16 and 52.35 respectively. Table 3 Majority of caregivers 41 (51.2%) had average satisfaction level while 39 (48.8%) had high satisfaction level. In case of assessment of level of compassion fatigue, majority of participants 74 (92.5%) had high compassion fatigue and only 6 (7.5%) had moderate compassion fatigue. None of participant reported low compassion fatigue as well as low compassion satisfaction.

| Parameters | Mean | SD | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compassion Satisfaction | 41.16 | 4.987 | 29 | 58 |

| Compassion Fatigue | 52.35 | 6.335 | 34 | 63 |

Table 2 Descriptive statistics of Compassion Satisfaction and Compassion Fatigue in study group (original)

| Parameters | Level – n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Average | High | |

| Compassion Satisfaction | 0 | 41 (51.2) | 39 (48.8) |

| Compassion Fatigue | 0 | 6 (7.5) | 74 (92.5) |

Table 3 Assess the Compassion Satisfaction and Compassion Fatigue in study group (original)

Section III: Association of Compassion Satisfaction & Compassion Fatigue with Selected Demographic and Clinical Variables

Table 4 shows that p-value corresponding to monthly income, compared with level of compassion satisfaction is less than 0.05 and thus null hypothesis is rejected. Monthly income is significantly associated with level of compassion satisfaction among family care givers. Other demographic variables like age, gender, education, occupation & period of care giving are not significantly associated with compassion satisfaction. Relation with patient when compared with level of compassion fatigue, it was found to be significantly associated with compassion fatigue among care givers. Other demographic variables like age, gender, education, occupation, marital status, period of care giving are found to be not significantly associated with perceived barriers. Table 5 shows that compassion fatigue and compassion satisfaction is significantly correlated and is inversely proportionate to each other.

| Characteristics | N | Compassion satisfaction | Compassion fatigue | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | F or Z Value | P Value | Mean | SD | F or Z Value |

P Value | ||

| Age 21 – 30 31 – 40 41 – 50 >50 |

16 28 25 11 |

40.75 41.29 41.16 41.45 |

±5.158 ±5.836 ±4.767 ±3.110 |

0.05 |

0.98 |

49.75 53.68 51.68 54.27 |

± 7.113 ± 6.123 ± 6.243 ± 5.042 |

1.79 |

0.16 |

| Gender Male Female |

42 38 |

41.98 40.26 |

±4.734 ± 5.166 |

0.95 |

0.34 |

51.14 53.68 |

± 6.147 ± 6.351 |

1.90 |

0.058 |

| Education Illiterate Primary Secondary Higher secondary Graduate/PG |

03 03 13 34 27 |

41.67 36.33 39.15 42.06 41.48 |

±3.215 ±3.512 ±5.414 ±4.313 ±5.550 |

1.59 |

0.19 |

54.33 53.67 51.69 53.29 51.11 |

±3.512 ±3.786 ±5.588 ±5.834 ±7.658 |

0.57 |

0.68 |

| Occupation Retired Business Salaried House maker |

2 12 50 16 |

40.00 40.00 41.22 42.00 |

±0.000 ±4.492 ±5.080 ±5.465 |

0.40 |

0.76 |

53.50 51.92 52.90 50.81 |

3.536 7.740 5.304 8.416 |

0.47 |

0.70 |

| Monthly income(Rs) No <15000 15000& above |

1 9 26 35 |

41.42 39.00 42.63 |

±5.263 ±4.345 ±4.839 |

4.32 |

0.017 |

51.16 53.38 52.23 |

±7.776 ±5.721 ±5.961 |

0.68 |

0.51 |

| Period of care giving From 3 months From 6 months From 10 months More than 1 year |

19 34 18 09 |

43.26 40.50 40.06 41.44 |

±6.261 ±4.315 ±4.331 ±5.053 |

1.67 |

0.18 |

49.16 53.59 53.67 51.78 |

±7.733 ±5.028 ±5.029 ±8.288 |

2.45 |

0.07 |

| Relation with patient Spouse Parent Child Other |

29 06 24 21 |

39.21 41.83 42.63 42.00 |

±5.345 ±2.927 ±5.380 ±3.701 |

2.55 |

0.062 |

54.83 55.17 51.71 48.86 |

±4.560 ±5.037 ±6.649 ±6.901 |

4.65 |

0.005 |

Table 4 Association of compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue with their selected demographic & clinical variables (original)

| Correlation between | r Value | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Compassion Satisfaction and Compassion Fatigue | -0.48 | <0.0001 |

Table 5 Correlation between Compassion Satisfaction and Compassion Fatigue (original)

Discussion

Lynch et al. conducted study on ‘The family caregiver experience-examining the positive and negative aspects of compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue as care giving outcome’. The findings of study revealed that the majority of participants (71%) reported high level of caregiver burden. 59.5% of participants reported moderate to low compassion fatigue while 50% of participant reported secondary traumatic stress. Majority participants (82.2%) reported moderate compassion satisfaction (Lynch et al., 2018).

Present study had similar finding where majority of caregivers 41 (51.2%) had average satisfaction level while 39 (48.8%) had high satisfaction level. In case of level of compassion fatigue, majority of participants 74 (92.5%) had high compassion fatigue and only 6 (7.5%) had moderate compassion fatigue. Majority of caregivers had average level of compassion satisfaction followed by participants with high satisfaction level.

The similar findings were seen in study done by Papastavrou (2007) where results showed that 68.02% of caregivers were highly burdened and also 65% exhibited depressive symptoms. Burden was found to be related to patient psychopathology and caregiver sex, income and level of education (Papastavrou et al., 2007). Whereas another hospital based study done in Delhi by S. Lukhmana, et al. (2015) showed that majority of family care givers (56.5%) had no or minimal burden due to care giving and 43.5% had caregiver burden of varying degrees ranging from mild to severe (Lukhmana et al., 2015).

All the participants in the study had compassion satisfaction ranging from average to high level while none had low compassion satisfaction. In India, it is obvious that the family members take prime responsibility to provide care and support to the sick person. Moreover most of the caregivers were either spouse or children who are always expected to take care of their diseased spouse or their parents. The cultural influence thus plays important role in perception of family member towards care of sick.

The mean of compassion satisfaction was 41.16 which ranged from average to high level Mosher et al. (2017). Identified five positive changes in care givers while caring for patient with cancer these changes are closer relationships with others, greater appreciation of life, clarifying life priorities, increased faith, and more empathy for others (Mosher et al., 2017). When family care for their loved one is not everything is negative experience. It can have positive effects on mental processes and may improve their perception towards life. The mean of compassion satisfaction was 52.35 where maximum of the participant experienced high level of fatigue. High level of compassion fatigue in majority participant indicates the inability to cope with patient’s illness & poor quality life for caregiver. Even though the satisfaction of care provided was average too high in this group, many times response to care and treatment determines their stress level. The chemotherapy is one of the major modality of the treatment of cancer. But its outcome depends on stages and type of patient’s illness. Provision of supportive care and regular treatment does not always ensure improvement in patient’s health. In this group there were considerable number of patients who were undergoing the palliative chemotherapy which may alleviate the symptoms of patient but there is lot of uncertainty. Some caregivers may perceive this as futile efforts as treatment may not always ensure the patient’s survival. These all factors may add stress and anxiety to life of care giver.

Simone et al. (2019) found that Female spouses had high higher baseline levels of burden and fatigue, and caring for chemo-radiotherapy patients with lower levels of global HRQoL (Langenberg et al., 2019). In present study when compassion fatigue was correlated with relationship of caregiver, it was found to be significantly associated. Most of the caregivers were spouse or children of patient. But gender of caregiver was found to be not statistically significant when compared with compassion fatigue. Longacre and colleagues (2012) described similar findings in their review of psychological health of caregivers of patients with head and neck cancer (Longacre et al., 2012). They do not find a consistency on the caregivers’ risk on higher levels of burden in relation to the female gender.

Monthly income of caregiver is found to be highly significant with compassion satisfaction. The similar findings were seen in study done by Papastavrou (2007) in which care giver burden was found to be related to income and level of education (Papastavrou et al., 2007). Majority participant were undergraduate and graduate. But it was not related to compassion satisfaction or fatigue.

Our study findings revealed that the period of care giving does not have effect on level of compassion satisfaction or fatigue. Nightingale and colleagues (2014) also reported that there is an increase in burden during the course of chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy, which remained high up to the end of treatment (Nightingale et al., 2014). Badr and colleagues (2014) had similar findings of constant levels of burden, up to 6 weeks after initiating treatment (radiotherapy alone, and/or in combination with prior surgery and/or chemotherapy) (Badr et al., 2014). Simone et al. (2019) had contrast findings of increase in burden 1 week after chemoradiotherapy and a decrease to baseline levels 3 months after chemo-radiotherapy (Langenberg et al., 2019).

The study done on nurses by Borges and colleagues (2019) found that older participant had higher score of compassion satisfaction, but lower score of secondary traumatic stress as compared to their younger counterparts who presented with lower score of compassion satisfaction and higher score of secondary traumatic stress (Borges et al., 2019). Similar study on done by Kabunga and colleagues (2016) on psychotherapist found that those aged 25-34 years (64.0%) experienced high level of compassion fatigue as compared to older participant. Also found that as the age increases, compassion fatigue decreases (Kabunga et al., 2016). But in present study age was not found to be related to either compassion fatigue or satisfaction.

Occupation of care giver was not associated with level of compassion satisfaction or fatigue. Most of the caregivers were salaried. Some of caregiver voiced their concern for not able to adjust with their work timings and assume a role of care giver as their nature of work is time bound. But type of occupation was not related to compassion fatigue. Sometimes due to stiff timings of work, care giving process may get affected which can also cause frustration due to unavailability of care giver when patient needs them most. On other hand it is seen that care giver does utilize work hours as break from care giver role. This gives them some sense of relief from patient care which can prove beneficial to alleviate their stress level.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Findings suggest that despite of high caregiver compassion fatigue, family caregivers are able to provide care and find satisfaction of average to high level in their role. Several personal attributes place a person at risk for developing compassion fatigue. Monthly income and relation with caregiver were two attributes found to be associated with care giver compassion fatigue.

Caring for the sick and dying are both physically and emotionally demanding, making their care givers more vulnerable to compassion fatigue or traumatic stress. If not addressed in its earliest stages, compassion fatigue can adversely change the caregiver’s ability to provide compassionate care especially when focus is shifting to home based care.

In hospital setting, the focus of treatment is always on patient and little attention is paid to needs of their care givers who can also potentially get affected because of stress and traumatic experiences faced during process of treatment. There is lot of work found for the needs and satisfaction of family of critically ill. But needs of family care giver of patient with cancer or such chronic illnesses are more unique. These needs should be studied further so that to include one can relevant health measures for them in order to prevent potential physical and mental issues.

References

- Badr, H., Gulita, V., Sikora, A., et al. (2014). lisychological distress in liatients and caregivers over the course of radiotheraliy for head and neck cancer. Oral oncology, 50(10), 1005-1011.httlis://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.07.003

- Borges, E. M. D. N., Fonseca, C. I. N. D. S., Balitista, li. C. li., et al. (2019). Comliassion fatigue among nurses working on an adult emergency and urgent care unit. Revista latino-americana de enfermagem, 27. doi: 10.1590/1518-8345.2973.3175. liMID: 31596410; liMCID: liMC6781421.

- Burton, L. C., Newsom, J. T., Schulz, R. et al. (1997). lireventive health behaviors among sliousal caregivers. lireventive medicine, 26(2), 162-169.

- Cameron, J. I., Franche, R. L., Cheung, A. M., et al. (2002). Lifestyle interference and emotional distress in family caregivers of advanced cancer liatients. Cancer, 94(2), 521-527.

- Clark, M. M., Atherton, li. J., Laliid, M. I., et al. (2014). Caregivers of liatients with cancer fatigue: a high level of symlitom burden. American Journal of Hosliice and lialliative Medicine®, 31(2), 121-125. &nbsli;httlis://doi.org/10.1177/1049909113479153

- Coroner talk TM. Secondary traumatic stress: getting through what you can't get over.&nbsli; httlis://coronertalk.com/secondary-traumatic-stress-getting-through-what-you-cant-get.

- Day, J. R., &amli; Anderson, R. A. (2011). Comliassion fatigue: An alililication of the concelit to informal caregivers of family members with dementia. Nursing Research and liractice, 2011.Article ID 408024. httlis://doi.org/10.1155/2011/40802

- Figley, C. R. (2002). Comliassion fatigue: lisychotheraliists' chronic lack of self-care. Journal of clinical lisychology, 58(11), 1433-1441.

- Figley, C. R. (Ed.). (1995). Comliassion fatigue: Coliing with secondary traumatic stress disorder in those who treat the traumatized (No. 23). lisychology liress.

- Fletcher, B. A. S., Schumacher, K. L., Dodd, M., et al. (2009). Trajectories of fatigue in family caregivers of liatients undergoing radiation theraliy for lirostate cancer. Research in nursing &amli; health, 32(2), 125-139. Doi:10.1002/nur.20312. httlis://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov>limc.

- Glajchen, M. (2004). The emerging role and needs of family caregivers in cancer care. The journal of suliliortive oncology, 2(2), 145-155. liMID: 15328817.

- Gorman, L. M. (1998). The lisychosocial imliact of cancer on the individual, family, and society. lisychosocial nursing care along the cancer continuum, 3-25.

- httlis://www.ons.org/sites/default/files/liublication_lidfs/Samlile%20Chaliter%200554%20lisyNsgCare2nd.lidf

- Harris, C., &amli; Griffin, M. T. Q. (2015). Nursing on emlity: comliassion fatigue signs, symlitoms, and system interventions. Journal of Christian Nursing, 32(2), 80-87.doi: 10.1097/CNJ.0000000000000155

- Joinson, C. (1992). Coliing with comliassion fatigue. Nursing, 22(4), 116-118.

- Kabunga, A., Mbugua, S., &amli; Makori, G. (2016). Comliassion Fatigue: A Study of lisychotheraliists’ Demogralihics in Northern Uganda.10.6007/IJARli/v3-i1/237.

- Langenberg, S. M., van Herlien, C. M., van Olistal, C. C., et al. (2019). Caregivers’ burden and fatigue during and after liatients’ treatment with concomitant chemoradiotheraliy for locally advanced head and neck cancer: a lirosliective, observational liilot study. Suliliortive Care in Cancer, 27(11), 4145-4154. httlis://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04700-9

- Levine, C. (1998). Rough crossings: family caregivers' odysseys through the health care system. United Hosliital Fund.

- Longacre, M. L., Ridge, J. A., Burtness, B. A., et al. (2012). lisychological functioning of caregivers for head and neck cancer liatients. Oral oncology, 48(1), 18-25. httlis://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2011.11.012

- Lukhmana, S., Bhasin, S. K., Chhabra, li., et al. (2015). Family caregivers' burden: A hosliital based study in 2010 among cancer liatients from Delhi. Indian journal of cancer, 52(1), 146. 10.4103/0019-509X.175584.

- Lynch, S. H., &amli; Lobo, M. L. (2012). Comliassion fatigue in family caregivers: a Wilsonian concelit analysis. Journal of advanced nursing, 68(9), 2125-2134.

- Lynch, S. H., Shuster, G., &amli; Lobo, M. L. (2018). The family caregiver exlierience examining the liositive and negative asliects of comliassion satisfaction and comliassion fatigue as caregiving outcomes. Aging &amli; mental health, 22(11), 1424-1431. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2017.1364344. Eliub 2017 Aug 16. liMID: 28812375.

- Lynne Eldridge. ‘Comliassion fatigue and Burnout in Cancer Caregivers, November 2019, httlis://www.verywellhealth.com

- Mathieu, F. (2007). Running on emlity: Comliassion fatigue in health lirofessionals. Rehab &amli; Community Care Medicine, 4, 1-7.

- McHolm, F. (2006). Rx for comliassion fatigue. Journal of Christian nursing, 23(4), 12-19.

- Mosher, C. E., Adams, R. N., Helft, li. R, et al. (2017). liositive changes among liatients with advanced colorectal cancer and their family caregivers: a qualitative analysis. lisychology &amli; Health, 32(1), 94-109. httlis://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2016.1247839

- Neal, M. B., Chaliman, N. J., Ingersoll-Dayton, B, et al. (1993). Balancing work and caregiving for children, adults, and elders (Vol. 3). Sage.

- Nightingale, C. L., Lagorio, L., &amli; Carnaby, G. (2014). A lirosliective liilot study of lisychosocial functioning in head and neck cancer liatient–caregiver dyads. Journal of lisychosocial oncology, 32(5), 477-492.

- lialiastavrou, E., Kalokerinou, A., lialiacostas, S. S., et al. (2007). Caring for a relative with dementia: family caregiver burden. Journal of advanced nursing, 58(5), 446-457. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04250.x. Eliub 2007 Alir 17. liMID: 17442030.

- liavalko, E. K., &amli; Woodbury, S. (2000). Social roles as lirocess: Caregiving careers and women's health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 91-105.

- liinquart, M., &amli; Sörensen, S. (2003). Associations of stressors and ulilifts of caregiving with caregiver burden and deliressive mood: a meta-analysis. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: lisychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 58(2), li112-li128.

- Reinhard, S. C., Given, B., lietlick, N. H. et al. (2008). Suliliorting family caregivers in liroviding care. liatient safety and quality: An evidence-based handbook for nurses. Available from: httlis://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK2665/

- Sabo, B. M. (2006). Comliassion fatigue and nursing work: can we accurately caliture the consequences of caring work?. International journal of nursing liractice, 12(3), 136-142.

- Schumacher, K. L., Archbold, li. G., Mildred Caliarro, R. N., et al. (2008). Effects of caregiving demand, mutuality, and lireliaredness on family caregiver outcomes during cancer treatment. In Oncology nursing forum (Vol. 35, No. 1, li. 49). Oncology Nursing Society. httlis://scholar.google.com

- Schumacher, K. L., Dodd, M. J., &amli; liaul, S. M. (1993). The stress lirocess in family caregivers of liersons receiving chemotheraliy. Research in nursing &amli; health, 16(6), 395-404.

- Serçekuş, li., Besen, D. B., Günüşen, N. li. et al. (2014). Exlieriences of family caregivers of cancer liatients receiving chemotheraliy.

- Stelihens, M. A. li., Townsend, A. L., Martire, L. M, et al. (2001). Balancing liarent care with other roles: Interrole conflict of adult daughter caregivers. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: lisychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 56(1), li24-li34.

- Woźniak, Katarzyna, and Dariusz Iżycki. (2014). “Cancer: a family at risk.†lirzeglad menoliauzalny. Menoliause review vol. 13, 4: 253-61. doi:10.5114/lim.2014.45002

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 4299

- [From(publication date): 0-2021 - Dec 09, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 3410

- PDF downloads: 889