A Framework for Ancillary Health Services Provided by Refugee and Immigrant-Run CBOs: Language Assistance, Systems Navigation, and Hands on Support

Received: 08-Aug-2019 / Accepted Date: 11-Sep-2019 / Published Date: 18-Sep-2019

Abstract

Building upon a model for primary health care services for refugee and immigrant communities, this study advances a specific framework for understanding three types of ancillary services: language assistance, systems navigation support, and hands-on support, provided by refugee- and immigrant-run community-based organizations (RI-CBOs). This place-based study allows examining organizational activities in a specific locality where context and structural factors (e.g., the density of health agencies and resources) are relatively similar across participating organizations, focusing on a Midwestern mid-sized U.S. city. Drawing on surveys and interviews with 16 RI-CBOs about healthcare- related activities, analysis entailed summary statistics and thematic analyses to build a synthesizing conceptual framework that incorporates existing literature on refugee/immigrant health with empirical findings. Our findings indicate that RI-CBOs are in a unique position to effectively liaise between the client and health care professional and to improve health education literacy.

Keywords: Health education; Ancillary health services; Refugee

Introduction

Providers call for health care and support systems that are resilient and flexible to be able to meet the unique needs of resettled refugees [1] and immigrants more broadly [2]. Migrants experience health with more time spent in the country of immigration relative to nonimmigrants across various dimensions of health [3]. Resettled refugees particularly experience unique health care challenges, including chronic illness, psychological conditions, infectious disease, and traumaassociated illnesses often attributable to their experiences of violence, torture, traumatic migration, and exposure to disease, compared to the native-born population [1,4]. Models of care that prioritize strong engagement with local communities and partnerships across health and social service organizations have been found to enhance health care [5-16] and health education for refugee and immigrant populations.

Conceptual framework

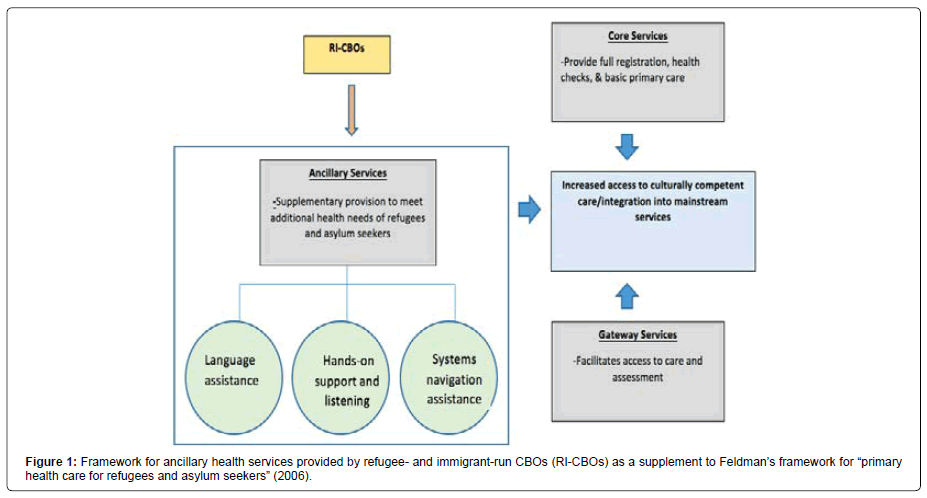

Feldman conceptualized three types of services in “primary health care for refugees and asylum seekers”: (a) gateway services facilitate access and assessment; (b) core services address basic primary care, health checks and registration; and (c) ancillary services “supplement and support core services’ ability to meet the additional health needs.”

Focusing on ancillary services, one key component is “close links with community-based organizations” (CBOs) [6]. Studies have documented how CBOs play a key role in improving health care access, as they understand the barriers the community faces and in turn, help to provide more appropriate, effective, and comprehensive services [5,6,9]. Models of care for immigrants and refugees, including Feldman’s framework, emphasize ongoing, collaborative processes with CBOs and other stakeholders [11] to connect medical providers with end users.

However, CBOs that are run specifically by refugees and immigrants remain unspecified within such frameworks [17]. Studies have examined the general range of activities conducted by refugeeand immigrant-run CBOs (RI-CBOs) [18,19], but their health-related activities specifically are understudied, even as they are considered integral to collaborative and locally based approaches to health care [5] and to understanding migrant health disparities [20]. This study aims to fill that gap in the literature pertaining to health-related activities of RICBOs and how they may fit within existing frameworks of immigrant and refugee health services provision.

Methods

Data collection

This study was conducted in a mid-sized U.S. city in the Midwestern region, considered a “new immigrant destination,” defined as an area that had not been a traditional immigrant gateway but has been seeing a new influx of immigrants [21]. Data were collected through written surveys and semi-structured interviews with leaders of 16 RI-CBOs. The survey pertained to organizational aspects: institutional links; use of spaces and resources; communication; advocacy activities; and range of activities in various domains, including health, immigration, and legal and social assistance. The survey, developed based on findings from a previous qualitative case study, was pilot tested, revised, and tailored to the current study site.

Participants

Inclusion criteria were refugee- and immigrant-serving organizational entities run by first- and second-generation immigrants or refugees. Applying the data collection approach by Gleeson and Bloemraad in their pioneering study of RI-CBOs, recruitment was initiated using the Internal Revenue Service’s database of registered nonprofit organizations and then expanded using snowball sampling. In our sample of 16 RI-CBOs, there were 8 African and 8 Asian RICBOs. Latin American RI-CBOs were excluded because there were very few refugees from that region being resettled in the city of study (Newbold and Danforth 2003) of the 16 RI-CBOs, seven were informal entities that had not filed/registered with official 501C3 nonprofit organization status with the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). Six RICBOs had an annual budget less than $10,000: four of those were not formalized as registered organizations with the IRS. Seven RI-CBOs had an annual budget between $10,000-25,000, and three RI-CBOs had an annual budget of more than $25,000. The number of years in existence ranged from 4 to 40, depending on population arrival (immigration or resettlement) into the city. For example, one RI-CBO that started in 2004 grew over 15 years to have two paid administrators and ten paid workers, while another RI-CBO that initially formed 40 years ago in 1978 still has no paid workers. Nine RI-CBOs were refugee-serving, and seven were largely targeting immigrants or immigrant-serving.

For the 16 RI-CBOs in our sample, there was an average of 35 unpaid volunteer-workers and leaders, ranging from 1–105; only four RI-CBOs had paid staff: 1, 3, 5 and 12 paid staff members. Across all 16 RI-CBOs, a given volunteer-worker provided 1–23 hours of assistance per week, with an average of five hours. One Congolese CBO stands out: even with a budget of less than $5,000 per year and not a formally registered organization, a volunteer- worker provides an average of 15 hours per week of assistance.

Results

Three domains of health-related ancillary services provided by RI-CBOs

Analyses of survey and interview responses found three domains of ancillary services provided by RI-CBOs, summarized in Table 1.

| Domain | Yes* | Specific Assistance | Yes | No |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Language services | 15 | Interpreting during medical appointments | 10 | 6 |

| Translating with medical documentation | 11 | 5 | ||

| Health systems navigation | 15 | Giving information and health-related referrals | 11 | 5 |

| Providing financial help in a crisis | 13 | 3 | ||

| Providing guidance in a crisis | 12 | 4 | ||

| Driving and accompanying to a medical appointment | 12 | 4 | ||

| Listening and hands-on support | 14 | Listening to a person's hardships | 14 | 2 |

| Providing hands-on assistance and helping them think about health-related issues | 12 | 4 | ||

| *Providing at least one of the specific forms of assistance in that domain. | ||||

Table 1: Health-related ancillary services provided by refugee and migrant-run CBOs (N=16).

A. Language assistance: All RI-CBOs serving refugees provided language assistance services, i.e., interpretation at doctors’ offices and translation of medical documents, except for the two organizations that served refugees from English-speaking African countries. A Laotian CBO leader shared:

• “So a lot of people in our community will reach out to us and say ‘I need a translator at the hospital, I need a translator taking me to (doctor), I need a translator for my mom, for an immediate family member.” A pan-African organization leader shared:

• “They meet us at the appointments, they tell us, ‘this is what we are facing, we don’t know the language, we don’t know whom to turn to.’ They always turn to us as an interpreter because we speak the same language and also able to speak English for them, so they come to us to advocate for them.”

B. Health care systems navigation assistance: Health care systems navigation assistance entailed providing information about and referrals for medication, providing guidance and financial help during a crisis, and driving or accompanying community members to medical appointments. All organizations provided at least one type of healthcare systems navigation assistance, except for one RI-CBO, which was a self-defined social-cultural association serving a long-established immigrant community.

We help them navigate the health system,” stated a Congolese CBO leader, and detailed:

• “People have Medicaid, but they are asking and don’t know whether to choose (this or that) health plan. They don’t know which one to take, which one their doctor takes. So we ask, ‘Who’s your primary health care provider?’ ‘I don’t know.’ So, you know, you have to start right there; then okay, let me look up, and then when you call you say ‘which insurance do you take the most?’ okay and then you fill out and you choose (the plan) for the family, put whatever email, and you call the health department, and you update the information. So we do about everything.”

Another interviewee, a Burmese RI-CBO leader, shared a similar account,

• “So for medical, sometimes we go with them to their appointments, sometimes they bring in their paperwork, which we help them fill out, about their health issues. And then, applying for health insurance, we help; (like if) they are not qualified for Medicaid, (health insurance companies) just send them their application like a whole pack, and then they don’t know what to do, and so we have to go online and submit.”

Not knowing how to navigate the health system can have consequences for displaced and migrant communities explained a pan- African CBO leader:

• “If you don’t fill out those applications then they cut off your assistance, and that’s how we help them and we teach them how it’s very important for them to fill out that paperwork because if they don’t, they are going to cut off their assistance, even their Medicaid, which is then going to be a struggle.”

C. “Hands-on support” and “listening” for health/medical issues: All RI-CBOs in the sample, except two, reported having “listened to a person’s hardships” and provided “hands-on support” in at least one health domain: mental health, physical health, or sexual health. The two exception organizations were CBOs run by long-established immigrant communities; one of which identified solely as a social group to promote cultural preservation and dissemination. Hands-on support included education about how to use medications, informal assessments, resources, and informal counseling. One Congolese CBO leader stated,

• “You know, sometimes they give people medications, like a prescription, and people they don’t know how to use medication and the prescription. So, when we have that problem, we call the doctor’s office and ask them for sure what the prescription says. (Also), sometimes they have difficulty finding the pharmacy, and something like that, so we provide those kinds of services.”

After explaining various services, a Liberian organization leader discussed the distinct role his CBO plays:

• “…most of these people would not have had special care and attention in other programs because of the language barrier or because of the cultural differences. So, with our (worker) coming from the same cultural background and used to have the same problem, they know specifically how to train these people and get them assimilated into the community or the healthcare system.”

He also compared supports provided by his CBO with those from mainstream agencies,

• “So if you were going to (programs) where they have a class of 50 students, and most of these students are American students, the instructor don’t have the time to come and spend that extra time with you because, not that you did not know what you were doing, but basically you are not understanding what the instructor was saying because of the pace and the culture.”

Some RI-CBO leaders discussed how they provide space where people can have emotional or mental health supports formally. According to a Laotian CBO leader:

• “When a family reaches out to us, if someone is going through depression…or someone in the family may have committed suicide, our organization provides support and finds medical resources to help them… We have volunteers who pick up the family and take them to the hospital, and translate and share what’s going on with the family.”

While on the surface, this activity involves transportation and linking to resources, it also involves accompaniment and support at a more personal level. Similarly, a Bhutanese CBO leader explained that they listen to people’s struggles, not anything “medically scientific” but more informal and culturally based. Indeed, support from someone who shares and understands one’s culture can be effective, as explained by a Congolese CBO leader:

• “You bring a Congolese family, but you don’t have the culture from the Congo, you don’t have the tradition, you don’t speak the language of the Congo, you don’t know the food we like in the Congo, you don’t know the relationships and the boundaries in terms of, you know, uncle, auntie, mother, son, daughter… You don’t understand all these layers of family interaction and you do it according to your model, and… there are so many things that you miss to understand. But then we will say, if you can bring me in a place where I am (a worker for) resettlement, I will speak to these people, I will explain to them, in my language, in their language, in a way that we understand and we answer their questions, and then the resettlement will be more smooth, more adjustable, more adequate, more healthy.”

Discussion

The language supports provided by RI-CBOs, for translation and interpretation, map directly onto service gaps and challenges specified in existing literature on migrant and refugee health. Health care providers experience difficulties finding and funding trained interpreters who can communicate with their refugee patients [22], creating communication challenges between patient and provider. Poor translation can create misunderstandings about health concerns, which in turn can lead to inappropriate treatment plans and referrals [23]. This is particularly problematic for addressing mental health concerns, as refugees use different words and phrases to describe symptoms of mental health compared to westerners [10]. The RI-CBO volunteers and workers thus function as interpreters and translators and are crucial to improving access to and quality of health care.

The RI-CBOs in our study provided direct one-on-one assistance for navigating the health care system, which has been identified and examined as a challenge in refugee and immigrant health [22]. Specific challenges include limited information on where to find services, lack of information and health education, transportation issues, confusion about the roles of different health professionals, and unfamiliarity with referral procedures [4,22-26]. It is difficult for refugee and immigrant patients to locate facilities and services, fill out medical forms, understand discharge paperwork, make appointments, and understand prescription use [23]. Refugees and immigrants express feeling confused about where to go to for health care services outside of nearby emergency rooms due to unfamiliarity with their neighborhood. Health insurance is a particularly problematic aspect for displaced populations, and one reason for low insurance rates among refugees is difficulty navigating the Medicaid marketplace due to limited English proficiency and/or health literacy [23]. Refugees and immigrants who do have insurance express frustration with the lack of communication between their providers, finding providers who are covered by their insurance, understanding their medical bills, and how to fill their prescriptions [27]. By helping migrants navigate health care and health insurance systems, RI-RCOs thus fill in a key role in improving access to health care. Beyond supports in language and systems navigation, RI-CBOs also provided hands-on support, and such services are culturally relevant and provide an informal, ad-hoc structure that is effective in reaching displaced populations (Gonzalez Benson 2017). Refugees and immigrants often have different beliefs about the role of the doctor; for instance, many refugees and immigrants do not agree with the provider’s treatment plan, as they prefer holistic and traditional healing services over western medicine [23]. Culturally insensitive care and distrust of or unfamiliarity with new or Western medical systems are barriers to health care access for migrant populations [22-25], and findings illustrate that RI-CBOs provide hands-on support that can address such barriers.

The RI-CBOs’ ancillary services fill specific gaps in health care services, but this raises questions of equity and social justice. Social responsibilities of the government in healthcare are thus de facto transferred upon local refugee communities without appropriate resources and supports. Results show that RI-CBOs that are refugeeserving and not registered as an NGO often have an annual budget less than $10,000, providing services voluntarily and communally. Although RI-CBOs’ ancillary services support core and gateway health care provision for refugees and asylum seekers (Feldman), their informality and fluidity contribute to their invisibility vis-à-vis health research, funding opportunities, and participatory/collaborative approaches to health services.

There are three things to consider regarding research limitations and future directions. First, data gained from this study’s survey and interviews provide results about the range of activities that RI CBOs perform, and further research could investigate processes and quality of services delivered. New research on the perspectives of service recipients can complement those of organizational leaders. Second, data analyzed in this study represents a cross-sectional view of organizational activities, and future studies could examine changes in the scope of activities over time to capture the shifting work of RICBOs. Third, findings help open new lines of inquiry pertaining to issues of standards of care, privacy, and confidentiality (Figure 1) [27].

Conclusion

Building upon Feldman’s conceptual framework (2006) for ‘services for primary health care for refugees and asylum seekers,’ our findings offer a more conceptual framework specific to refugee- and migrant-run CBOs. Whereas existing literature has focused on mainstream CBOs as playing key roles in health services for refugees and immigrants, our study contributes new empirical data and extends existing frameworks. Our findings point to RI-CBOs as untapped resources and potential partners for health and medical institutions. This study thus raises questions about the nature and extent of links and collaborations between RI-CBOs and healthcare institutions. Collaborations could include organizational capacity building via training and education for RI-CBOs, and sharing of funding and resources. Such links and collaborations would not only strengthen RI-CBOs’ existing services but also support medical institutions by facilitating care that is culturally competent, accessible, and responsive.

References

- Langlois EV, Haines A, Tomson G, Ghaffar A (2016) Refugees: Towards better access to health-care services. Lancet 387: 319-321.

- The Lancet (2016) Healthy migration needs a long-term plan. Lancet 387: 312.

- Newbold B, Danforth J (2003) Health status and Canada's immigrant population. Soc Sci Med 57: 1981-1995.

- Müller M, Khamis D, Srivastava D, Exadaktylos AK, Pfortmueller CA (2018) Understanding refugees’ health. Semin Neuro 38: 152-162.

- Chaudhary N, Vyas A, Parrish EB (2010) Community based organizations addressing South Asian American health. J Commun Health 35: 384-391.

- Feldman R (2006) Primary health care for refugees and asylum seekers: A review of the literature and a framework for services. Public Health 120: 809-816.

- Griswold KS, Kim I, Scates JM (2016) Building a community of solution with resettled refugees. J Community Med Health Educ 6: 1-5.

- Griswold KS, Pottie K, Kim I, Kim W, Lin L (2018) Strengthening effective preventive services for refugee populations: Toward communities of solution. Public Health Rev 39: 3.

- Haley HL, Walsh M, Maung NHT, Savage CP, Cashman S (2014) Primary prevention for resettled refugees from Burma: Where to begin?. J Community Health 39: 1-10.

- Jorm AF (2012) Mental health literacy: Empowering the community to take action for better mental health. Am Psychol 67: 231-243.

- Nazzal KH, Forghany M, Geevarughese MN, Mahmoodi V, Wong J (2014) An innovative community-oriented approach to prevention and early intervention with refugees in the United States. Psychol Serv 11: 477-485.

- Pottie K, Batista R, Mayhew M, Mota L, Grant K (2014) Improving delivery of primary care for vulnerable migrants: Delphi consensus to prioritize innovative practice strategies. Can Family Physician 60: e32-e40.

- Sackey D, Kay M, Nicholson C, Peterson P (2016) Connecting practice, research and policy to improve refugee health outcomes. Int J Integrated Care 16: A93.

- Shah S, Yun K (2018) Interest in collaborative, practice-based research networks in pediatric refugee health care. J Immigr Minor Health 20: 245-249.

- Suurmond J, Rupp I, Seeleman C, Goosen S, Stronks K (2013) The first contacts between healthcare providers and newly-arrived asylum seekers: A qualitative study about which issues need to be addressed. Public Health 127: 668-673.

- Weine SM (2011) Developing preventive mental health interventions for refugee families in resettlement. Fam Process 50: 410-430.

- Gleeson S, Bloemraad I (2013) Assessing the scope of immigrant organizations. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 42: 346-370.

- Gonzalez Benson O (2017) Refugee community organizations as actors upon resettlement. Forced Migration Review, University of Oxford Press.

- Lacroix M, Baffoe M, Liguori M (2015) Refugee community organizations: From the margins to mainstream? A challenge and opportunity for social workers. Int J Social Welfare 24: 62-72.

- Edberg M, Cleary S, Vyas A (2011) A trajectory model for understanding and assessing health disparities in immigrant/refugee communities. J Immigr Minor Health 13: 576-584.

- Marrow HB (2005) New destinations and immigrant incorporation. Perspectives on Politics 3: 781-799.

- Mirza M, Luna R, Mathews B, Hasnain R, Hebert E, et al. (2014) Barriers to healthcare access among refugees with disabilities and chronic health conditions resettled in the U.S. Midwest. J Immigrant Minority Health 16: 733-742.

- Potocky-Tripodi M (2002) Best Practices for Social Work with Refugees and Immigrants. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Bellamy K, Ostini R, Martini N, Kairuz T (2015) Access to medication and pharmacy services for resettled refugees: A systematic review. Aust J Primary Health 21: 273-278.

- Lawrence J, Kearns R (2005) Exploring the ‘fit’ between people and providers: Refugee health needs and health care services in Mt Roskill, Auckland, New Zealand. Health Soc Care Community 13: 451-461.

- Pottie K, Greenaway C, Feightner J, Welch V, Swinkels H, et al. (2011) Evidence-based clinical guidelines for immigrants and refugees. CMAJ 183: E824-E892.

- Boise L, Tuepker A, Gipson T, Vigmenon Y, Soule I, et al. (2013) African refugee and immigrant health needs: Report from a community-based house meeting project. Prog Community Health Partnersh 7: 369-378.

Citation: Gonzalez Benson O, Pimentel Walker AP, Yoshihama M, Burnett C, Asadi L (2019) A Framework for Ancillary Health Services Provided by Refugee and Immigrant-Run Cbos: Language Assistance, Systems Navigation, and Hands on Support. J Community Med Health Educ 9:665.

Copyright: © 2019 Gonzalez Benson O, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Usage

- Total views: 6225

- [From(publication date): 0-2019 - Dec 21, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 5308

- PDF downloads: 917