Research Article Open Access

Confronting the Forthcoming Death: A Classic Grounded Theory

Carina Werkander Harstäde1* and Anna Sandgren21Post doc., Department of Health and Caring Sciences, Linnaeus University, Växjö, Sweden

2RN, PhD, The Center for Collaborative Palliative Care, Department of Health and Caring Sciences, Linnaeus University, Växjö, Sweden

- *Corresponding Author:

- Carina Werkander Harstäde

Reg. nurse, PhD in Caring Sciences

Lecturer in palliative care, Post doc. Centre for Collaborative Palliative Care,

Department of Health and Caring Sciences

Linnaeus University Växjö, Sweden

Tel: +4673 986 81 58

E-mail: carina.harstade@lnu.se

Received date: October 28, 2016; Accepted date: November 21, 2016; Published date: November 22, 2016

Citation: Harstäde CW, Sandgren A (2016) Confronting the Forthcoming Death: A Classic Grounded Theory. J Palliat Care Med 6:289. doi: 10.4172/2165-7386.1000289

Copyright: © 2016 Harstade CW, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Palliative Care & Medicine

Abstract

Objective: The aim of this study was to develop a classic grounded theory of patients in palliative care. Methods: A classic Grounded Theory methodology was used to conceptualize patterns of human behavior. Twenty-seven interviews with patients in palliative care and two autobiographies written by persons receiving palliative care were analyzed. Result: “Confronting the forthcoming death” emerged as the pattern of behavior through which patients deal with their main concern, living in uncertainty of a death foretold. The theory involves four strategies; Seeking concrete knowledge, Shielding off, Seeing things through, and Embracing life. Holding on to hope and Suffering are also ever present. Conclusion: The theory shows that there is no easy way straight ahead; patients strive to confront the situation as well as they can, both wanting and not wanting to know what lies ahead. For health professionals, knowledge about how patients use different strategies, which can be used in tandem or succession, or shifted back and forth between over time, to confront their imminent deaths, can create an awareness of how to encounter patients in this uncertainty.

Keywords

Grounded theory; Palliative care; Patients’ perspective; Qualitative research

Introduction

The goal of palliative care is to improve the quality of life of both patients and their families as they face life-threatening and life-limiting diseases [1,2]. This is typically done via prevention and relief of suffering through early identification, assessment, and treatment of pain and other problems, whether physical, psychosocial, or spiritual [3].

Entering palliative care is in many ways a sad and overwhelming experience [4]. Knowing that there is no cure for the disease, and that the patient’s time is now much limited, can cause despair and sorrow among patients and family members. At the same time, many individuals strive to cope with this situation and find comfort in the knowledge that they are part of a context (e.g. a family or group) [5]. Patients often try to fight the despair that accompanies their entering into palliative care by maintaining normalcy in their lives [6-8]. Thus, family and friends are important for patients and can often be a central part of their care [9,10]. In particular, being a family caregiver is seen as being at the frontline of care [11] and can encompass significant physical, emotional, and social challenges that are often demanding and exhausting [12,13]. The hardships associated with caring for a family member have been documented in the palliative care literature [14,15]. However, several researchers state that less attention has been given to how patients perceive their own situation in palliative care [16,17]. Several possible reasons for this are the difficulty of recruiting patients at this stage of life [18] and fear of distressing or causing harm to patients when seeking their views [19]. Attempting to circumvent these issues by exploring the perspectives of family caregivers is not a valid path, given evidence for the differing assessments of physical and psychological issues between family caregivers and patients [20]. Given this perspective, it is of importance to comprehensively understand how patients receiving palliative care cope with their situation. The aim of the present study was therefore to develop a grounded theory (GT) of patients receiving palliative care, exploring their main concerns and how they handle this concern.

Method

This study used the classic GT methodology, which aims to conceptualize patterns of human behaviour [21-25]. Data were obtained from interviews and biographical books. Thirteen patients with incurable diseases receiving the services of a palliative home care team in southern Sweden were interviewed. Seven were women and six were men, and their mean age was 68 years (median 65 years). Patients were suffering from cancer, congestive heart failure, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Professionals at the palliative home care team asked patients during a home visit if they would be willing to participate in an interview about their life situation; at this time, they also were given written information about the study.

All interviews were performed in participants’ homes except one, which was performed at the participant’s workplace. The interviews were informal, open-ended conversations and patients were encouraged to speak openly about their situation when living with an incurable disease. The interviewer (first author), who is well experienced in performing qualitative interviews, followed the patients’ stories and was open and sensitive to what they narrated. Open questions were used to encourage the patients to explore the issues further, so a greater depth of understanding was reached.

The interviews lasted for 45–90 minutes and took place during the year 2015. Field notes were written out during and after each interview, and served as the basis for data analysis. Memos were written concurrently with the data collection and the data analysis as a way to keep track of ideas about connections between emerging concepts [22,24].

The field notes were used in the generation of concepts, which began with open coding of the data. Open coding involves analysing the text line by line, as soon as possible after each interview, by asking various questions: What do these data reflect? What category does this incident indicate? What is actually happening in these data? What is the patients’ main concern? How do they continually handle this concern? Asking these questions helped the researcher be theoretically sensitive and avoid mere description of the data. Furthermore, they helped emphasize the properties that repeated themselves in the data instead of focusing on single incidents. The open coding process was accompanied by constant comparison, where initial codes are compared with each other as they emerge, newly generated concepts are compared to new codes, and concepts are compared to other concepts. Theoretical sampling [21,22,24] was used to guide the interviews; in other words, new ideas that emerged during interviews were used to steer subsequent interviews to elucidate those ideas. GT does not give consideration to the representativeness of a sample but instead aims to collect data to refine and elaborate emerging categories and focus on categories related to the core concept and emerging theory [21,22,24].

Following open coding, the process of selective coding was initiated, wherein the collected data and codes were delimited into precise categories and related to the core concept. Concurrent with this coding process, we performed a secondary analysis of nine interviews previously conducted with patient in the late phase of palliative care [26]. Furthermore, further data from five interviews with patients in palliative care, not yet published, were analysed, along with two biographical books [27,28]. The purpose of this secondary analysis was to compare and refine the coding done in the first 13 interviews to ensure full saturation of the concepts. During the analysis, more memos were written and memo sorting was performed. The coding continued until theoretical saturation was reached, which means that no new categories emerged from the analysis of new data [22,24]. To remain on the conceptual level (rather than the descriptive), we continually related the conceptual categories and properties to each other. According to Glaser [25], the theory is not the voice of study participants—rather, it is an abstraction of the actions and meanings of individuals in the research area.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Regional Ethical Board in Linköping, Sweden (2014/304-31). All participants received written and oral information about the aim of the study and the possibility of withdrawing their participation at any time without need to give reasons for doing so. Confidentiality was assured according to ethical research guidelines [29]. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Results

Living in uncertainty of a death foretold emerged as the main concern of patients in palliative care. They are living with incurable disease and are being sure of what the future will bring and at the same time they do not know how and when this will happen. This knowledge makes them live in an involuntary waiting and at the same time trying to live each day in the present. The uncertainty is a frustrating insight that is impossible to eliminate.

Confronting the forthcoming death

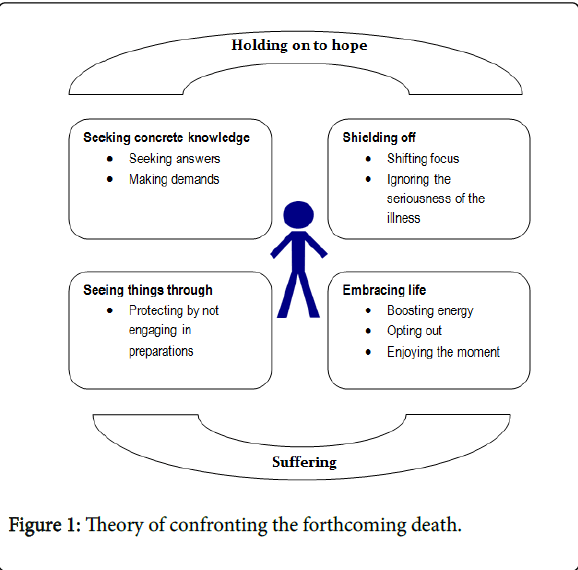

Living in uncertainty of a death foretold is resolved in the process of confronting the forthcoming death, where patients in different ways try to deal with the knowledge that they are going to die (Figure 1).

Confronting the forthcoming death is performed in different ways; Seeking concrete knowledge , Landing in awareness, Accepting with clear insight, Shielding off, Seeing things through, and Embracing life. During the whole process of confronting the forthcoming death, Holding on to hope and Suffering are always present. Living in uncertainty thus is handled in different ways and there is no foregone conclusion that only one way is used. Still there seems to be a start in seeking concrete knowledge from which the patient moves forward and undertakes different ways of handling the situation. Patients can stay in one strategy, different strategies can be used at the same time, and patients can go back and forth between different strategies over time. There are also triggers that can make patients go from one strategy to another, such as: hearing bad/good news, feeling worse/ better in the disease. These triggers can e.g. move the patients back into seeking concrete knowledge once more and from that point start the process again, and move forward into different strategies.

During the whole process of confronting the forthcoming death, the strategy holding on to hope is generally always present. Patients, despite having knowledge of the disease, continue to hope for recovery or at least to obtain more time to be with family and friends. This is a way of ensuring that they do not give in to the disease completely. To continue seeking information about the disease and possible treatments for it, as well as discuss this information with family, friends, physicians, and other health professionals. Part of this strategy involves negotiating where patients deal with the situation of being aware of the forthcoming death by discussing and arguing with oneself, physicians, other health professionals, or God. Such negotiating involves promising to be a better person, to do better, to follow health advice, and to comply with treatments and therapies; in other words, anything that can buy some more time for them.

Another all-encompassing result is suffering. Patients suffer in different ways. For instance, patients might suffer it out (i.e., express their suffering), but this can be difficult because of patients’ fear of saddening their family or friends, who are seen as the most important persons in the patients’ lives; in other words, patients want to spare these individuals from further pain. These cause patients to keep all of their suffering to themselves—namely, to suffer on their own. Although this method can work, occasionally there is no way of hiding it—thus, patients suffer it out. This can be done with family and friends witnessing the suffering without interfering and it can also be done with family/friends who manage to be there with them when they go into suffering. They can cry and curse together. Here there is no need to spare; instead the situation is processed by suffering together. Suffering is impossible to escape and is always present more or less. During the course of the disease patients now and then fall into distress and suffer it in or suffer it out and then try to pull themselves together again. Thus the suffering can be a way of venting frustration and sadness.

Seeking concrete knowledge: It refers to patients’ seeking out confirmation of what is happening in their bodies. Specifically, patients feel that something is wrong and find it difficult to disregard this worry. Thus, they seek explanations in order to understand what is happening to them. Inherent to this strategy is the fear of what will be revealed. Seeking concrete knowledge is done through seeking answers , and making demands.

In seeking answers , patients attempt to find ways of obtaining the relevant knowledge. This process can be long and complicated, depending on how patients’ concerns are met by health professionals. For instance, receiving different answers from different physicians creates insecurity in patients, so that they no longer know what to believe or how to relate to the information. They can remain with this lack of awareness for some time, which is prolonged by their receiving evasive answers and misleading assessments from health care professionals, thus generating feelings of insecurity and frustration. Patients can also receive straight, informative answers that provide them with knowledge about what is happening to them, creating an awareness that is both wanted and not wanted.

Making demands refers to how patients take a stand and insist to be told the truth or to be told what is suspected. This requires that patients believe in their own strength to act. If patients feel that they are not able to achieve this on their own, they might recruit family members or friends to support them in making these demands. These supporters can merely be present or can speak on patients’ behalf. Making demands can also be about urging physicians to try new or different treatments and therapies, and patients occasionally change physicians because they feel that they are not being listened to.

When patients are seeking concrete knowledge and obtaining answers, they move on with this information in different ways. They can be landing in awareness where they have something real to relate to, a knowledge about what is going on. Patients feel that after a period of insecurity, they have something substantial that can lead to thoughts on how to handle the situation. It is easier to decide what to do and what not to do next. However, while the frustration and insecurity of not knowing their situation fades, it can be replaced with similar feelings about the fact that they have an incurable disease. The landing in awareness gives patients a choice: either they can accept the situation or reject it. In accepting with clear insight, patients realize that the disease will ultimately lead to death. This insight gives them opportunities to put their suspicion, fear, and confirmation in order and face what is coming. This can be a way of engaging in more important things instead of nurturing a hope of recovery.

Confronting the forthcoming death can thus result in landing in awareness and accepting with clear insight; moreover holding onto hope and suffering are almost always present. The consequences of holding on to hope and suffering permeate the entire process and can influence how patients move on in their confrontation. Indeed, patients who are landing in awareness might be overwhelmed by their situation, and thus, rather than accepting it, they can turn to the strategy of shielding off . The awareness can also be a trigger to accepting with clear insight and move on to the strategy of seeing things through.

Shielding off: Shedding off occurs when patients find that insight into their forthcoming death is too distressing. As such, they avoid taking this information in and, rather than confronting it, shielding it off in their minds. This strategy can also be employed before patients seek any information at all—obtaining even the slightest suspicion might make them turn away from seeking the truth. In this way, shielding off can appear at different stages on the path to the forthcoming death: It can be a direct answer to a suspicion that something is wrong or a strategy of handling concrete information. Shielding off comprises two sub-strategies: shifting focus and ignoring the seriousness of the illness.

When patients engage in shifting focus, they turn their attention from the forthcoming death towards a situation that is less difficult for them to handle. For example, they might plan and go on a trip or immerse themselves in restoration of the house or apartment. Triggers such as hearing bad news or experiencing a worsening of symptoms can, in particular, divert patients’ strategies for confronting the forthcoming death, causing them to shift focus, more or less consciously, to matters that have nothing to do with the disease.

Ignoring the seriousness of the disease is closely related to shifting focus because it deals with not wanting to understand how grave the situation is. However, it differs in that, even when patients are aware of the seriousness of the disease and treatments that might palliate symptoms or prolong life, they still choose to ignore the situation. Again, it can be done more or less consciously. The metaphor of a curtain is apt—they pretend that what cannot be seen merely does not exist. By drawing this curtain, patients can then turn their attention away from their imminent death less distressing matters and act as if life goes on as normal. While ignoring the seriousness of the disease can be seen as a respite, it can also be a constant reminder that the patients have something they must inevitably confront.

Seeing things through, in contrast, reflects a desire to not leave complicated tasks for loved ones after their death—in other words, a desire to make life easier after the patients have died. It helps patients deal with concerns about how the family will live on. Often, patients will try to quickly make these arrangements because they worry whether or not they will be able to finish these tasks before they die. If they realize that they are not able to finish in time—because of a lack of time or their own strength—they often experience sadness and frustration. In other words, they feel that it is a matter of not living up to what they think and feel they shall accomplish. At the same time, actually making these arrangements brings sorrow because patients realize that the arrangements are all about a preparation for not being here anymore, and that there is no escape from this awareness. When employing this strategy, patients can also be landing in awareness and accepting with clear insight, since their efforts to “see things through” bring even more awareness of what is happening. The increasing awareness can also imply greater acceptance.

One consequence of trying to see things through can be that families have difficulties in coping with patients’ efforts. Indeed, sometimes, family members might try to oppose the efforts. For them, these efforts make the forthcoming death too imminent, and thus too difficult to cope with. These family members want to escape from the reality of their loved one dying. In these situations, patients employ the sub-strategy of protecting by not engaging in preparations, which can be seen as more or less a contradiction of seeing things through. This can lead to frustration because patients feel that they are trapped between making the necessary arrangements for the family and protecting them from the sadness brought on by these arrangements. Thus, regardless of how they handle it, patients experience a great deal of sadness.

If patients are landing in awareness and maybe also accepting their situation this can help them accomplish seeing things through more or less, they have the possibility of employing the strategy of embracing life . In employing this strategy patients understand and accept their forthcoming death, which leads to them placing much more importance on seeking out moments with good, positive energy. This is partly due to a sense of security, as patients know that they have a network of family and friends. However, it also concerns knowledge that they can live a normal life because of the privilege of experiencing yet another day, even when there is not much happening in their lives. Overall, embracing life refers to a search for aspects of life that give energy and an avoidance of so-called “energy thieves.” Such energy helps patients in managing the uncertainty. Embracing life comprises the sub-strategies: boosting energy, opting out, and enjoying the moment .

Boosting energy refers to choosing activities or people that provide energy to patients and can help in adapting to uncertainties brought on by the disease. Having family and friends, pets, nature, and enjoying time on one’s own are examples of how patients spend time in a treasured, energy-boosting way. Such activities are a positive force in motivating patients to try to live a little longer and feel good. Living in uncertainty is considered a heavy load for both the body and soul, and having the ability to see a silver lining in everyday life grants patients a sense of strength. Furthermore, persisting in this way demands the strength to embrace what life brings.

When patients engage in opting out , they remove the influence of energy-exhausting activities or people (i.e., “energy thieves”) from their lives. These can be people seeking acknowledgement for doing a good deed by visiting the patient but only talking about their own ailments and complaints. They can also be meetings that patients do not want to attend or relatives who require constant attention but who give nothing back. Regardless of whether situations or persons create these experiences, patients make a conscious decision to not let themselves be dragged down by these energy thieves and instead simply opting them out.

Finally, when enjoying the moment, patients live in the present and allow themselves to feel good. They rejoice days where they do not experience pain or nausea and savour happy thoughts. Despite being well aware of the situation, they might still feel a temporary spark of hope that life is not so bad for them. This is a way of creating distance from the disease while still not engaging in shielding off. It is reasoning where patients are well aware of the disease, knowing what way it will eventually take but choosing to enjoy the moments of feeling good.

Discussion

Classic GT was chosen for this study to elucidate the main concerns of patients in palliative care. In line with Glaser’s [24] thinking, it is not likely that this could have been done if the focus had been on predefined problems. The theory developed - Confronting the forthcoming death —cannot claim to represent the entire behaviours of patients in palliative care; still, such confrontation strategies employed by patients seemed to be fundamentally present.

According to classic GT the validity is assessed in terms of the criteria of fit, workability, relevance, and modifiability [22]. This GT study was considered to have adequate fit because the categories presented emerged from the data collected, rather than from any preestablished theoretical perspective. Furthermore, constant comparison was used in the process of creating the theory. The study has workability because the theory enables prediction, explanation, and interpretation of how people in palliative care perceive their lives. In other words, the theory could identify and explain what the main concern is for the people involved in the study. Similarly, the core category - confronting the forthcoming death—was the lowest common denominator that sufficiently explained the main concern for the people involved. Further, the theory attempts to explain variations in the ways that the patients resolved the main concern. Relevance was established by showing that the theory was relevant to the studied area. In this sense, the main concern of patients was the focus, and the results will hopefully benefit health professionals working in palliative care. Finally, modifiability means that the theory can be modified if new data are obtained. Glaser [22,23,24] suggests that this means that a GT should be abstracted from the time, place, and persons involved. Although the idea of confronting the forthcoming death is, in many ways, bound to the palliative care field (given the field’s emphasis on awareness of end of life), these confrontational strategies may be useful in handling other circumstances where persons are living in uncertainty. After modification, this theory might contribute to understanding how persons live in uncertainty in various situations and settings.

Living in uncertainty of a death foretold emerged as the main concern. A similar concern was described in past studies among other patients, such as those with HIV [30], chronic heart failure [31], prostate cancer [32], and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [33]. These examples are also involved in the specific context of palliative care. Receiving a diagnosis of an incurable illness can be like entering a world with no future. An earlier study shows how patients who struggle with this awareness can shift their behaviour from being prospective into being perceptually present, allowing them to savour each moment [34]. This acceptance was also seen in Black [35], who showed that approaching the end-of-life often concerns a balance between understanding and acceptance.

Holding on to hope is an overarching strategy used during the confrontation process. It is nearly always present and even when patients are well aware of the seriousness of the disease, they never fully lose hope. Holding on to hope is a well-known strategy identified in nursing research, such as hoping to live longer and/or see a cure for the disease [36], hoping for a miracle [36,37], and hoping to be the one to beat the odds [38]. The findings in this study coincide with those of Benzein, Norberg, and Saveman [39], who showed that holding onto hope was a means of trying to find meaning, picture a better outcome, or make life easier. Holding on to hope can be seen as a tension between two dimensions of hope: namely, to hope for something, which refers to the hope of being cured, and living in hope, which signifies a reconciliation and comfort with life and death [39]. The first dimension pervaded the confrontational strategies identified in the present theory, while the latter was mainly present in embracing life. The patients also demonstrate what might seem to be an unrealistic hope for recovery. However, this, as Fitzgerald Miller [40] suggests, begs the question: do patients with such unrealistic hopes need to be confronted with reality? Can hope lead to pointless therapies that then increase suffering? Cotter and Foxwell [41] suggest that unrealistic hope for recovery or long-term survival can interfere with opportunities to say goodbye to loved ones or obtain emotional support. However, hope can also [42] be a crucial resource for adaption and can be seen as a coping mechanism that helps individuals cope with the forthcoming separation and death. Cotter and Foxwell [41]also point out the importance for patients in palliative care to be able to imagine future moments of happiness and satisfaction. This could be compared to Benzein et al. [39] and Benzein and Berg [43], who suggests that patients in palliative care must dream about their possibilities and envision futures and goals, even if these are unlikely to occur.

Suffering is also present throughout the whole process of confronting the forthcoming death. Even when patients embrace life, the knowledge of their forthcoming death still lingers in their minds, which can make them fall into intermittent periods of suffering. One might argue that suffering is a purely negative means of confronting death, but it has been argued as having some positive outcomes. For instance, Ellis et al. [44] showed how suffering can be defined as a transformation. This coincides with what the present theory refers to with suffering it out . It can lead to an altered view of oneself and how one can live through the suffering, a development of a more coherent self and a sense of meaning.

Landing in awareness is an important part of confronting the forthcoming death. This transition signifies an important tension between the limits of the patient’s body, medicine, and the desires of patient, family, and health professionals. It involves a type of acceptance where the transition from life-prolonging to life-enhancing care is apparent, despite the accompanying difficulty and sadness [45]. Broom, Kirby, and Good [46] showed how acceptance helps to limit decision making in palliative care and thereby produce an interpersonal framework of “good dying.” The present study shows how patients’ acceptance can make them embrace life, suggesting that such acceptance is a reconciliation with the forthcoming death. Gaining knowledge also gives them a platform to continue working and deciding on what to do next. By being active, asking questions, and demanding answers, their situation can be easier to bear. This can be compared to the ways of handling uncertainty described by McKechnie, MacLeod and Keeling [47]. Awareness of the forthcoming death can also help patients begin seeing things through by preparing for the family’s life after their death, similar to what McPherson, Wilson, and Murray [16] called “alleviating burden to others and making preparations.” Importantly, these preparations are not always welcomed by family and friends, which can be frustrating to patients and places them in between the urge to prepare and the desire to protect their loved ones by not preparing; this finding coincides with Raffin et al. [48]. This point is particularly necessary for health professionals to recognize when meeting patients and their families in palliative care.

Shielding off can be interpreted as a method of confrontational coping with negative events that attempts to reduce suffering [49]. It is a method characterized by a profound effort to turn away from the forthcoming death. Notably, it may be difficult sometimes to separate shielding off from embracing life ; however, in embracing life , patients live with the awareness while simultaneously trying to make the most of the here and now. Embracing life show the importance of being with loved ones and enjoying life. Previous findings have similarly emphasized families’ experiences of being present and living in the moment with their loved ones as a way of generating a sense of stability and peace [50]. Other studies pointed out how patients often seize the opportunity to live in the present as a way of “living while dying” and “dying while living” by celebrating life [51].

Seeking out and obtaining information about the seriousness of a disease can be difficult to handle, and patients may confront through suffering ; at the same time, this information can provide a sense of relief in that patients are correct in their suspicions. The frustration and uncertainty of not knowing is replaced by a frustration and uncertainty with the situation. Roberts [52] and Sandgren et al. [53] both showed how patients in palliative care have varied preferences about how and when they want to be informed of the seriousness of their illnesses. Most patients preferred to be told gradually and in a manner personalized to their emotional response, but some never wanted to hear any bad news at all.

Roberts [52] also showed how health professionals can be in a contradictory position in that they must struggle between not lying to patients while also knowing that revealing the possible complications of the disease will heavily burden patients. In contrast, Kirklin [54] pointed out that if health professionals fail to tell patients the whole, unrevised, and often disturbing truth, patients would be denied opportunities to make decisions about how they wish to spend the rest of their lives. Obviously, there is no easy answer as to how health professionals must act in the complicated issue of truth-telling. It is thus of great importance to adopt a patient-centred approach to care, involving viewing every patient as a subjective human being. This involves, as noted by Nyatanga [55] the need to be flexible with care to reflect the personal needs of each patient, something that is even more important in palliative care where there might be only one chance to get things right.

It is of considerable importance that health professionals are aware of how fundamental the experience of living in uncertainty can be in palliative care. Patients know what lies ahead for them, but at the same time, they do not know how and when it will happen. Handling this uncertainty can, as this study shows, be done in a number of different ways and in the directions of accepting the situation and escaping it. Thus, health professionals can meet patients that act in what can be seen as understandable ways where they curse the situation or are filled with sadness. However, they might also meet patients who do not seem to care about the serious condition they are in, who instead seem to be feeling good and enjoying life and do not talk about what lies ahead.

Conclusion and Implications

In conclusion, the theory confronting the forthcoming death involves several strategies that explain patients’ behaviour patterns when living in uncertainty. These strategies can sometime seem contradictory, which may explain how patients behave in palliative care. The theory makes it evident that there is no easy way straight ahead; thus, patients strive to confront the forthcoming death as well as they can from day to day, both wanting and not wanting to know what lies ahead. For health professionals, knowledge about this theory and how patients use different strategies, which can be used in tandem or succession, or shifted back and forth between over time, to confront their imminent deaths, can create an awareness of how to encounter patients in this uncertainty. It can contribute to health professionals being better prepared to respond to the patients’ needs as well as give an insight into the complexity of this kind of caring. Since this theory has emerged from what patients in palliative care see as their main concern, this knowledge can also be of importance in educational settings where person-centred care is emphasized. The theory is also significant to take into account as patients’ experiences can be building blocks in development of good guidelines in palliative care. Nevertheless, further research is necessary concerning how acceptance, submission and reconciliation are experienced by patients in palliative care.

Acknowledgement

A sincere thank you to R.N Jenny-Ann Johansson who was a tremendous help in getting in contact with the patients involved in the study.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

No conflict of interest has been declared by the authors.

Funding

Financial support was received from the Kamprad Family Foundation for Entrepeneurship, Research, & Charity. [Grant number 20152002].

References

- Amorim Mendes A (2014) The time that remains: Self-identity and temporality in cancer and other life-threatening illnesses and in Messianic experience. Palliative and Supportive Care. 12: 165–168.

- Becker R (2009) Palliative care 1: principles of palliative care nursing and end-of-life care. Nursing Times. 105: 14–6.

- World Health Organization (2016) WHO definition of palliative care.

- Lundin T (2005) Den oundvikligasorgen (The inevitable sorrow). I B Beck-Friis, P Strang (eds) Palliative medicine 67-80.

- Rosengren K, Gustafsson I, Jarnevi E (2015) Every second counts: Women’s experience of living with ALS in the end-of-life situations. Hom Health CarManagPrac. 27: 76-82.

- Bruce A, Schreiber R, Petrovskaya O, Boston P (2011) Longing for ground in a ground(less) world: a qualitative inquiry of existential suffering. BMC 10: 1-9.

- Dawson S, Kristjanson L (2003) Mapping the journey: Family carers’ perceptions of issues related to end- stage care of individuals with muscular dystrophy or motor neuron disease. J Palliat Care19: 36-42.

- Houldin AD (2007) A qualitative study of caregivers’ experiences with newly diagnosed advanced colorectal cancer.OncolNurs Forum. 34: 323–330.

- Aoun SM, Kristjanson LJ, Currow DC, Hudson P (2005) Caregiving for the terminally ill: At what cost? Palliat Med19: 551–555.

- Grande G, Ewing G (2008) Death at home unlikely if informal carers prefer otherwise: Implications for policy. Palliat Med 22: 971–972.

- Milligan C (2006) Caring for older people in the 21st century: Notes from a small island. Health Place 12: 320-331.

- Eggenberger SK, Nelms TP (2007) Being family: The family experience when an adult member is hospitalized with a critical illness. J ClinNurs16: 1618–1628.

- Hudson P (2004) Positive aspects and challenges associated with caring for a dying relative at home. Int J PalliatNurs10: 58–65.

- Diwan S, Hougham GW, Sachs GA (2004) Strain experienced by caregivers of dementia patients receiving palliative care: Findings from the Palliative Excellence in Alzheimer Care Efforts (PEACE) program. J Palliat Med 7: 797-807.

- Grunfeld E, Coyle D, Whelan T, Clinch J, Reyno L, et al. (2004) Family caregiver burden: Results of a longitudinal study of breast cancer patients and their principal caregivers. CMAJ 170: 1795-1801.

- McPherson C, Wilson K, Murray M (2007) Feeling like a burden: Exploring the perspectives of patients at the end of life.SocSci Med 64: 417-427.

- Wright D, Hopkinson J, Corner J (2006) How to involve cancer patients at the end of life as co-researchers. Palliat Med 20: 821-827.

- Addington-Hall J (2002) Research sensitivities to palliative care patients. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 11(3): 220-224.

- Hughes N (2006) User involvement in cancer care research. Eur J Palliat Care 13: 248–250.

- Hinton J (1996) How reliable are relatives’ retrospective reports of terminal illness? Patients and relatives’ accounts compared. SocSci Med 43: 1229-1236.

- Glaser B, Strauss A (1967) The discovery of grounded theory. Strategies for qualitative research.

- Glaser B (1978) Advances in methodology of grounded theory - Theoretical sensitivity. Mill Valley, The Sociology Press.

- Glaser B (1992) Basics of grounded theory analysis. Mill Valley, The Sociology Press.

- Glaser B (1998) Doing grounded theory: Issues and discussions. Mill Valley, The Sociology Press.

- Glaser B (2003) The grounded theory perspective II – Description’s remodeling of grounded theory methodology. Mill Valley, The Sociology Press.

- WerkanderHarstäde C, Andershed B (2004) Good palliative care: how and where? The patients’ opinions. J HospPalliatNurs 6: 12.

- Lindquist U-C (2004) Ro utanåror (Row without oars). Stockholm: Nordstedts.

- Noll P (1991) The face of death. London: Penguin Books Ltd.

- Vetenskapsrådet (2011) God Forskningssed (Good research codex). Vetenskapsrådetsrapportserie 1:2011.

- Sajjadi M, Rassouli M, Bahri N, Mohammadipoor F (2015) The correlation between perceived social support and illness uncertainty in people with Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome in Iran. Indian J Palliat Care 21: 231-235.

- Dudas K, Olsson L-E, Wolf A, Swedberg K, Taft C, et al. (2012) Uncertainty in illness among patients with chronic heart failure is less in person-centred care than in usual care. Eur J CardiovascNurs 12: 521-528.

- Bailey D, Wallace M, Mishel M (2007) Watching, waiting and uncertainty in prostate cancer. J ClinNurs16: 734-741.

- King S, Duke M, O’Connor B (2009) Living with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/motor neurone disease (ALS/MND): decision-making about ’ongoing change and adaption’. J ClinNurs 18: 745-754.

- Ellingsen S, Roxberg Å, Kristoffersen K, Rosland JH, Alvsvåg H (2013) Entering a world with no future – A phenomenological study describing the embodied experience of time when living with severe incurable disease.Scand J Caring Sci27: 165-174.

- Black J (2011) What are patients’ priorities when facing the end of life? A critical review. Int J PalliatNurs 17: 294-300.

- Nilmanat K, Promnoi C, PhungrassamiT, Chailungka P, Tulathamkit K, et al. (2015) Moving beyond suffering – The experiences of Thai persons with advanced cancer. Cancer Nurs 38: 224-231.

- Widera E, Rosenfeld K, Fromme E, Sulmasy D, Arnold R (2011) Approaching patients and family members who hope for a miracle. J Pain Symptom Manage 42: 119-125.

- Sterba K, Zapka J, Gore E, Ford M, Ford D, et al. (2013) Exploring dimensions of coping in advanced colorectal cancer: Implications for patient-centered care. J Psycho Oncol31: 517-539.

- Benzein E, Norberg A, Saveman BI (2001) The meaning of the lived experience of hope in patients with cancer in palliative home care. Palliat Med 15: 117-126.

- Fitzgerald Miller J (2007) Hope: A Construct Central to Nursing. Nurs Forum 42: 12-19.

- Cotter V, Foxwell A (2015) The meaning of hope in the dying. In: B Ferrell, N Coyle, J Paice (eds.) Oxford Textbook of palliative nursing (4th Ed.) New York: Oxford University Press, pp: 475-487.

- Coward D, Reed P (1996) Self-transcendence: A resource for healing at the end of life. Issues Ment Health Nurs 17: 257-288.

- Benzein E, Berg A (2005) The level of and relation between hope, hopelessness and fatigue in patients and family members in palliative care. Palliat Med 19: 234-240.

- Ellis J, Cobb M, O’Connor T, Dunn L, Irving G, et al. (2015) The meaning of suffering in patients with advanced progressive cancer. Chronic Illness 11: 198-209.

- MacArtney J, Broom A, Kirby E, Good P, Wootton J, et al. (2015) On resilience and acceptance in the transition to palliative care at the end of life. Health 19: 263-279.

- Broom A, Kirby E, Good P (2012) Specialists’ experiences and perspectives on the timing of referral to palliative care: A qualitative study. J Palliat Med 15: 1248-1253.

- McKechnie R, MacLeod R, Keeling S (2007) Facing uncertainty: The lived experience of palliative care. Palliat Support Care 5: 367-376.

- RaffinBouchal S, Rallison L, Moules N, Sinclair S (2015) Holding on and letting go: Families experiences of anticipatory mourning in terminal cancer. J Death D ying. 72: 42-68.

- Sorato D, Osório F (2015) Coping, psychopathology, and quality of life in cancer patients under palliative care. Palliat Support Care13: 517-525.

- Andersson M,Ekwall A, Hallberg I, Edberg AK (2010) The experiences of being next-of-kin to an older person in the last phase of life. Palliat Support Care 8: 17-26.

- McWilliam C, Ward-Griffin C, Oudshoom A, Krestick E (2008) Living while dying/dying while living: older clients’ sociocultural experiences of home-based palliative care. JHospPalliatNurs. 10: 338-349.

- Roberts H (2008) Patients with terminal illness and their healthcare providers preferred a dosed and gradual process of truth-telling. Evid Based Nurs 11: 128-128.

- Sandgren A, Thulesius H, Peterson K, Fridlund B (2010) Living on hold in palliative cancer care. The Grounded Theory Review. 9: 79-100.

- Kirklin D (2007) Truth telling, autonomy and the role of metaphor. J Med Ethics 33: 11-14.

- Nyatanga B (2013) Palliative care in the community using person-centred care. British Br J Community Nurs 18: 567-568.

Relevant Topics

- Caregiver Support Programs

- End of Life Care

- End-of-Life Communication

- Ethics in Palliative

- Euthanasia

- Family Caregiver

- Geriatric Care

- Holistic Care

- Home Care

- Hospice Care

- Hospice Palliative Care

- Old Age Care

- Palliative Care

- Palliative Care and Euthanasia

- Palliative Care Drugs

- Palliative Care in Oncology

- Palliative Care Medications

- Palliative Care Nursing

- Palliative Medicare

- Palliative Neurology

- Palliative Oncology

- Palliative Psychology

- Palliative Sedation

- Palliative Surgery

- Palliative Treatment

- Pediatric Palliative Care

- Volunteer Palliative Care

Recommended Journals

- Journal of Cardiac and Pulmonary Rehabilitation

- Journal of Community & Public Health Nursing

- Journal of Community & Public Health Nursing

- Journal of Health Care and Prevention

- Journal of Health Care and Prevention

- Journal of Paediatric Medicine & Surgery

- Journal of Paediatric Medicine & Surgery

- Journal of Pain & Relief

- Palliative Care & Medicine

- Journal of Pain & Relief

- Journal of Pediatric Neurological Disorders

- Neonatal and Pediatric Medicine

- Neonatal and Pediatric Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry: Open Access

- OMICS Journal of Radiology

- The Psychiatrist: Clinical and Therapeutic Journal

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 12998

- [From(publication date):

November-2016 - Aug 30, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 12069

- PDF downloads : 929