The Effect of Ignoring Statistical Interactions in Regression Analyses Conducted in Epidemiologic Studies: An Example with Survival Analysis Using Cox Proportional Hazards Regression Model

Received: 07-Dec-2015 / Accepted Date: 31-Dec-2015 / Published Date: 15-Jan-2015 DOI: 10.4172/2161-1165.1000216

Abstract

Objective: To demonstrate the adverse impact of ignoring statistical interactions in regression models used in epidemiologic studies.

Study design and setting: Based on different scenarios that involved known values for coefficient of the interaction term in Cox regression models we generated 1000 samples of size 600 each. The simulated samples and a real life data set from the Cameron County Hispanic Cohort were used to evaluate the effect of ignoring statistical interactions in these models.

Results: Compared to correctly specified Cox regression models with interaction terms, misspecified models without interaction terms resulted in up to 8.95 fold bias in estimated regression coefficients. Whereas when data were generated from a perfect additive Cox proportional hazards regression model the inclusion of the interaction between the two covariates resulted in only 2% estimated bias in main effect regression coefficients estimates, but did not alter the main findings of no significant interactions.

Conclusions: When the effects are synergic, the failure to account for an interaction effect could lead to bias and misinterpretation of the results, and in some instances to incorrect policy decisions. Best practices in regression analysis must include identification of interactions, including for analysis of data from epidemiologic studies.

Keywords: Effect modification; Cox proportional hazards model; Regression analysis; Simulation; Statistical interaction; Type 2 diabetes

163735Introduction

The terms interaction effect and effect modification, or effectmeasure modification are often used interchangeably, particularly for health related research in epidemiology [1]. From an epidemiologic prospective effect modification refers to a situation where the effect of one predictor variable (e.g., exposure) on the outcome is dependent on the values of some other covariates [1,2]. From a statistical prospective, an interactive multivariable regression model could be fit by including the product of two or more predictor variables along with their corresponding individual variables in regression models [1].

Identification of statistical interactions in a regression model is important because this could lead to significant public health implications. For example, using data from an Epidemiologic Study on the Insulin Resistance Syndrome (DESIR) cohort, Gautier A. et al. (2010) found significant interactions between baseline BMI categories and higher waist circumference in relation to progression to type 2 diabetes using a logistic regression model [3]. Based on their findings the authors concluded that for reducing incidence of type 2 diabetes in their study population, it is important to monitor and prevent increases in waist circumference, particularly for those with BMI <25 kg/m2. Similarly, Hanai K. et al. examined whether obesity modifies the association of serum leptin levels with the progression of diabetic kidney disease by including an interaction term between the obesity and leptin in a Cox proportional hazards regression model [4]. The authors found a significant interaction between leptin levels and obesity, hence concluded that obesity modifies the effect of leptin on kidney function decline in patients with type 2 diabetes. On the other hand, in an Iranian sex-stratified cohort study which was conducted to investigate risk factors for incidence of type 2 diabetes using Cox proportional hazards regression model [5], the authors recommended different preventive strategies by sex because of their findings that along with central adiposity in women and general adiposity in men, a lower education level conferred a higher risk for incidence of diabetes among men. Using data from Second Manifestations of Arterial Disease (SMART) study, Verhagen S. N. et al. investigated the relation between high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) levels and the incidence of type 2 diabetes in patients with manifest arterial disease or any cardiovascular risk factors [6]. The authors found a significant interaction between gender and hsCRP in relation to incidence of type 2 diabetes in a Cox proportional hazards model. They concluded that manifest arterial disease patients with high hsCRP plasma levels are at increased risk to develop type 2 diabetes and this risk is more pronounced in female than male patients.

While some epidemiologic studies investigated and found significant interactions or effect modifications, in a majority of epidemiologic studies the interactions or effect modifications are not explored. We estimated the relative frequency of lack of exploring potential interactions in regression analyses by conducting a nonsystematic search in PubMed for the period, January 2004 to December 2013. Since interactions and effect modifications are usually explored via multivariable regression models and different terms such as “multivariable regression” or “multiple regressions” or “regression” are used in regression analysis [7], we restricted our search only to “multivariable regression” and “multiple regression”, which are often used interchangeably by epidemiologists. Next, among papers using the terms “multivariable regression”, “multiple regression” or “regression”, we searched for the terms “statistical interaction”, “effect modifier”, “effect modification”, or “heterogeneity of effect”. The result revealed that 4.4% of the published studies in PubMed that used terms “multivariable regression” (or “multiple regression”) have used terms related to interactions, effect modifications, or heterogeneity of effects in their publications.

Although some of the publications may not be related to epidemiologic studies, or the terms interaction or heterogeneity may be used under different context, our search revealed that a majority of investigators may not explore interactions or effect modifications when conducting regression analysis.

The aim of this study is to demonstrate the adverse effects of ignoring interactions in regression models by conducting simulation studies in different scenarios. Specifically, we study the effect of ignoring interactions in a Cox proportional hazards regression model. In addition, to demonstrate the importance of including interactions in regression models in real life epidemiologic studies, we compared results from additive and interactive models using data from the Cameron County Hispanic Cohort (CCHC) [8]. For this we specifically focused on investigating the role of peripheral white blood cells (WBC) counts, WBC differential counts and BMI in association with the time to incidence of type 2 diabetes while controlling for the effect of other known type 2 diabetes risk factors.

Materials and Methods

Simulation study for investigating interactive effects

Dataset generation: To assess the impact of ignoring the interactive effects, we simulated data from two fully specified Cox proportional hazards regression models h(t|x)=h0(t)exp(β′x) where h(t|x) is the hazard rate at time t for an individual with risk vector x, β is the vector of regression coefficients, and h0(t) is the baseline hazard, with two predictor variables that had only additive or interactive effects. In addition different magnitudes for the coefficient of the interaction term were considered. All Cox proportional hazards regression models that were used for simulation are presented in Table 1. For each of four scenarios 1000 replications, with sample sizes of 600 each, were generated in a manner that are described in the following.

| Scenario | Cox proportional hazards regression model* |

|---|---|

| 1 | h(t/ x)=h0 (t) exp (2x1+x2) |

| 2 | h(t/ x)=h0 (t) exp (2x1+x2+0.5x1 x2) |

| 3 | h(t/ x)=h0 (t) exp (2x1+x2+x1 x2) |

| 4 | h(t/ x)=h0 (t) exp (2x1+x2+1.5x1 x2) |

Table 1: Cox proportional hazards regression models used for different scenarios of the simulation study

In order to simulate data from the underlying Cox models, the effect of the covariates have to be translated from the hazard functions to the survival times, as documented in the literature [9,10]. It can be shown that the survival time for exponential survival random variable could be written as T=-In[S(t)]/[λexp(β′x)] , where S(t) is the probability of surviving beyond time t and λ>0 is the scale parameter of the exponential distribution. When S(T) has a uniform distribution between 0 and 1 (i.e., S(T)~U(0,1)) then-In[S(T)] is exponentially distributed with parameter 1, and T is exponentially distributed with parameter λ′ (x)=λexp(β′x). To create survival time data we generated exponentially distributed survival times T with scale parameters λ′ (x)=λexp(β′x) with an arbitrarily chosen constant baseline hazard rate λ=h0(t) [9,10]. Next, we generated exponentially distributed censoring time c with arbitrary chosen constant baseline censoring rate λ1 [10]. To generate right-censored survival time data the observed time to event was defined as minimum of the survival T and censoring variable C. That is generated observed time to events were (time to event=T when T<C), where the censoring status variable had a value of 1 if the time to event is censored (C>T) or 0 otherwise [11,12]. The parameters of the exponential distribution were determined by several iterations such that the censoring rate in each simulated dataset was higher than 30%. While in Cox proportional hazards regression model the predictor variables are not required to be normally distributed, for this simulation study the pre-specified continuous variable x1 was generated from normal distribution with mean 6.4 and variance 2.25 that represents the distribution of WBC counts observed in the CCHC data. The pre-specified binary variable x2 was generated as Bernoulli random variable with probability of success p=0.5, that closely represents the distribution of obese status of individuals in the CCHC subset. The regression coefficients in all scenarios were arbitrarily set to β1=2 and β2=1.

Model comparisons: Using the simulated datasets Cox models with and without interaction terms were fitted under each of the scenarios. To summarize the simulation results, estimates for each regression coefficient and the corresponding standard errors from the 1000 replications were averaged for each of the scenarios.

For comparing coefficient estimates between correctly specified and misspecified Cox regression models percentage of bias was calculated using  ,where

,where  is the average of the estimated regression coefficient

is the average of the estimated regression coefficient  over 1000 replications and β is the true value of the regression coefficient. Overall accuracy of the estimates was assessed by mean squared error (MSE) which is the sum of the variance of the estimator and the squared bias

over 1000 replications and β is the true value of the regression coefficient. Overall accuracy of the estimates was assessed by mean squared error (MSE) which is the sum of the variance of the estimator and the squared bias

All simulations were performed with Stata 12 [13] using survsim module [14,15] and the statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 [16].

Empirical example for demonstrating interaction effects using Cameron County Hispanic Cohort Data

To demonstrate the importance of identifying interactions in epidemiologic studies, in this section we referred to an earlier finding from analyses of CCHC data with Cox proportional hazards regression model [8]. Briefly, using data from 636 participants in the CCHC, this study assessed crude and adjusted effects of total and differential WBC counts (lymphocytes, monocytes, and granulocytes), C-reactive protein (CRP), and Body Mass Index (BMI) in relation to time to progression to type 2 diabetes in Mexican Americans. All participants without any evidence of type 2 diabetes after the baseline visit, death or lost-tofollow up were considered as censored at their last observation dates. Other covariates, such as age at the time of the event or censoring, gender, family history of diabetes, pre-diabetes status, smoking, and triglycerides were also included in the regression analysis. The effect modification of continuous BMI and BMI levels (e.g., BMI<25 (normal), 25 ≤ BMI<30 (overweight), and BMI ≥30 (obese)) on total and differential WBC counts were evaluated. In this study, the presence of the interactions was tested by including the product of the dichotomized BMI as BMI ≥35 and BMI <35 with total or differential WBC counts in the models [17] and by using a likelihood ratio test for the nested models with and without an interaction term. Also, we conducted multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models stratified analyses by BMI categories to compare stratum specific hazard ratios with those obtained from our final interactive Cox proportional hazards regression models.

Cox proportional hazards regression model assumptions for the functional form of the continuous covariates (e.g., the linear relationship between log cumulative hazard and a covariate) and proportionality assumption of the hazards of all covariates were evaluated before and after including the interaction term in the model. Our result indicated that family diabetes history and pre-diabetes status did not satisfy the proportional hazards assumption; hence all models that included these two variables were stratified by these variables by including strata statement in SAS Proc Phreg [18]. Details regarding the model development are described elsewhere [8].

Calculation of hazard ratios in the presence of interactive effects

The calculations of Hazard Ratios (HRs) from an interactive Cox proportional hazards model is different from the calculations of HRs from an additive model. For example in the following interactive Cox proportional hazards model.

(1)

(1)

Where x1 is a continuous variable and x2is a dichotomous variable with values 1 or 0, the HRs for x1 by the levels of variable x2in (1) can be written as HR=exp (x1 (β1 + 0β3))=exp (x1β1) when x2=0, and the HR for x1 is HR=exp (x1 (β1 + 0β3)) when x2=1.

In contrast in an additive Cox proportional hazards regression model.

(2)

(2)

the HR for x1 is exp (x1β1) adjusted for the effect of the covariate x2.

Results

Simulation study

Table 2 shows the results of the analysis of simulated data with Cox proportional hazards regression model (1) without the interaction term. The coefficient estimate for variable x1 in the correctly specified (model with no interaction term) and misspecified model (model with interaction term) had the same percentage of bias (0.5%) and MSE (0.01). However the estimate for coefficient of variable x2in the misspecified model was more biased (2%) and less accurate (MSE=0.72) compared to the correctly specified model (bias=0%, MSE=0.02). As expected the estimate for coefficient of the interaction term in the misspecified regression model (i.e., true model was additive but we fitted an interactive model) was very small and negligible which led to very similar estimates of 2.013 for the true coefficient of variable x1 that was 2. The estimated coefficient of variable x1 was 2.01 when adjusted for the effect of variable x2 in the correctly specified model. As expected the model with interaction term did not impact x1 or x2 estimates significantly. In addition based on the interactive (misspecified) model when x2=0 the HR for x1 is 7.49 and when x2=1 the HR for x1 is 7.46. Whereas based on the additive (correct) model the HR for x1 is 7.46, adjusted for the effect of x2. This illustrates that in the case of a perfect additive Cox proportional hazards regression model the inclusion of the interaction of the covariates does not have a significant impact on main effect regression coefficients estimates, hence on the estimated hazard ratios.

| Parameter estimates | Correct Model† | Misspecified Model‡ |

|---|---|---|

| Estimated coefficient of x1 ± SE | 2.01 ± 0.09 | 2.01 ± 0.11 |

| %bias in estimated coefficient of x1 | 0.50% | 0.50% |

| MSE* | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Estimated coefficient of x2 ± SE | 1 ± 0.12 | 0.98 ± 0.85 |

| %bias in estimated coefficient | 0.00% | -2.00% |

| MSE* | 0.02 | 0.72 |

| Estimated coefficient of x1*x2 (1 vs. 0) ± SE | - | 0.003 ± 0.11 |

Table 2: Findings from multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression model fitted using generated data in scenario 1.

Table 3 shows the results of the analyses on simulated data with Cox proportional hazards models with interaction term under scenarios (2), (3) and (4). Compared to the correctly specified models, the regression coefficient estimates for variables x1 and x2 in the misspecified models in all scenarios were more biased and less accurate as the magnitude of the coefficient of the interaction term increased [10]. Specifically, the bias increased from 352% to 894% and MSE increased from 12.43 to 80.18, as the magnitude of the coefficient of the interaction term increased from 0.5 to 1.5.

| Parameter estimates | Data generated with b3=0.5 (Model 2) | Data generated with b3=1.0 (Model 3) | Data generated with b3=1.5 (Model 4) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Misspecified Model† | Correct Model‡ | Misspecified Model† | Correct Model‡ | Misspecified Model† | Correct Model‡ | |

| Estimated coefficient of | 2.26 ± 0.09 | 2.01 ± 0.11 | 2.42 ± 0.09 | 2.01 ± 0.11 | 2.52 ± 0.1 | 2.01 ± 0.12 |

| X1 ± SE | ||||||

| %bias in estimated coefficient | 13.00% | 0.50% | 21.00% | 0.50% | 26.00% | 0.50% |

| MSE* | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.19 | 0.01 | 0.29 | 0.01 |

| Estimated coefficient of X2 ± SE | 4.52 ± 0.21 | 1 ± 0.83 | 7.51 ± 0.3 | 1.04 ± 0.91 | 9.94 ± 0.39 | 1.03 ± 1.01 |

| %bias in estimated coefficient | 352.00% | 0.00% | 651.00% | 4.00% | 894.00% | 3.00% |

| MSE* | 12.43 | 0.7 | 42.49 | 0.85 | 80.18 | 1.03 |

| Estimated coefficient of X1*X2 ± SE |

- | 0.5 ± 0.12 | - | 1 ± 0.14 | - | 1.5 ± 0.16 |

| %bias in estimated coefficient | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | |||

| MSE* | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | |||

‡Correct model is the model with interaction term X1*X2 as well as the main effects of X1 and X2

*Mean squared error is defined as the sum of the variance of the estimator and the squared bias

Table 3: Findings from multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models fitted using generated data in scenarios 2, 3 and 4.

Findings from the empirical study

The results from the analyses of CCHC data are presented in Tables 4 and 5 including estimates for the coefficients and their standard errors. In our final models we identified significant interactions between dichotomous BMI (i.e., obese categories) and total WBC (p-value=0.0137), granulocytes (p-value=0.0291), and lymphocytes (p-value=0.0478) after adjusting for the effect of age at the time of the event or censoring, gender, smoking, and triglycerides and stratified for family history of diabetes and pre-diabetes status by including strata statement in SAS Proc Phreg. Because of the significant interaction between dichotomous BMI and total WBC, granulocytes, and lymphocyte, we calculated estimated adjusted hazard ratios for WBC counts, granulocytes, and lymphocyte by different levels of the interacting variable BMI.

| Variables | Unadjusted models* | Adjusted models* |

|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | |

| Models with total WBC count x109/L: Hazard ratio for WBC by the level of the interacting variable BMI | ||

| WBC in BMI≥35 | 1.29 (1.07-1.55) | 1.49 (1.20-1.85) |

| WBC in BMI<35 | 1.09 (0.97-1.23) | 1.09 (0.97-1.85) |

| Models with Lymphocytes x109/L: Hazard ratio for Lymphocytes by the level of the interacting variable BMI | ||

| Lymphocytes in BMI≥35 | 2.60 (1.49-4.53) | 2.95 (1.57-5.52) |

| Lymphocytes in BMI<35 | 1.45 (0.98-2.12) | 1.43 (0.98-2.09) |

| Models with Monocytes x109/L: Hazard ratio for Monocytes by the level of the interacting variable BMI | ||

| Monocytes in BMI≥35 | 3.36 (0.46-24.64) | 3.71 (0.44-31.19) |

| Monocytes in BMI<35 | 1.88 (0.41-8.68) | 1.73 (0.40-7.42) |

| Models with Granulocytes x109/L: Hazard ratio for Granulocytes by the level of the interacting variable BMI | ||

| Granulocytes in BMI≥35 | 1.26 (1.00-1.60) | 1.49 (1.14-1.94) |

| Granulocytes in BMI<35 | 1.06 (0.92-1.22) | 1.07 (0.92-1.23) |

| Models with Granulocytes x109/L and Lymphocytes x109/L: Hazard ratio for Granulocytes by the level of the interacting variable BMI | ||

| Granulocytes in BMI≥35 | 1.2 (0.95-1.52) | 1.46 (1.19-1.92) |

| Granulocytes in BMI<35 | 1.02 (0.88-1.20) | 1.02 (0.86-1.20) |

Table 4: Findings (SI units) from interactive multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models of time to first type 2 diabetes using Cameron County Hispanic Cohort data, 2003-2014.

| Variables | BMI groups | |

|---|---|---|

| BMI<35 | BMI≥35 | |

| HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | |

| Models with total WBC count x109/L | ||

| WBC | 1.10 (0.97, 1.24) | 1.47 (1.14, 1.89) |

| Models with Lymphocytes x109/L | ||

| Lymphocytes | 1.43 (0.98, 2.1) | 3.25 (1.58, 6.7) |

| Models with Monocytes x109/L | ||

| Monocytes | 1.80 (0.43, 7.55) | 3.13 (0.38, 26) |

| Models with Granulocytes x109/L | ||

| Granulocytes | 1.07 (0.92, 1.24) | 1.42 (1.06, 1.9) |

| Models with Granulocytes x109/L and Lymphocytes x109/L | ||

| Granulocytes | 1.04 (0.89, 1.22) | 1.36 (1.002, 1.83) |

Table 5: Findings (SI units) from multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models* for time to first type 2 diabetes among participants in BMI stratified Cameron County Hispanic Cohort, 2003-2014.

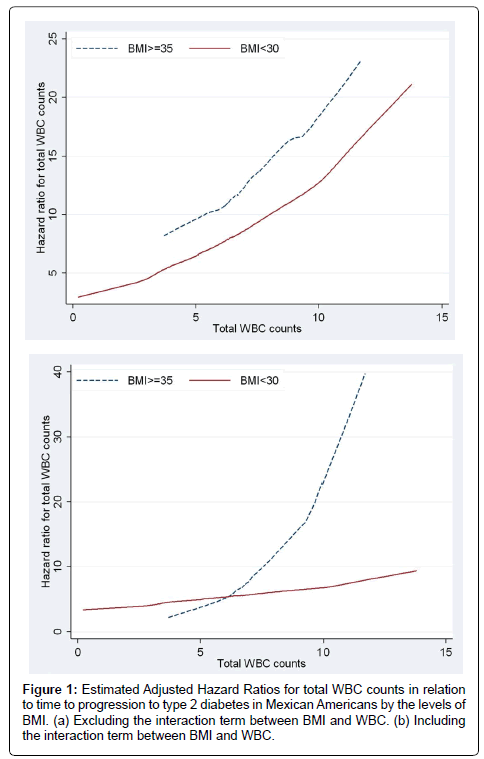

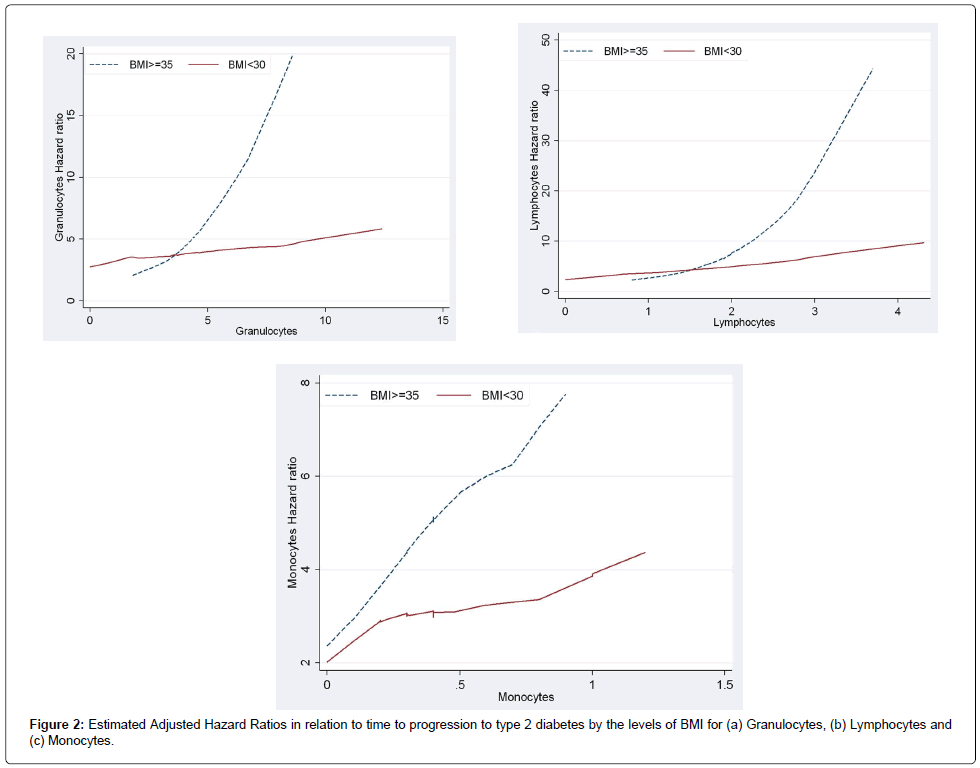

Figure 1a and 1b present the plots of estimated adjusted hazard ratios for total WBC counts for BMI ≥35 and BMI<35 under a model with no interaction and a model including interaction term between BMI and total WBC counts. Under the additive model (i.e., with no interactions) the lines for the hazard ratios were somewhat parallel and the vertical distance between them represented the BMI adjusted hazard ratio for WBC counts (Figure 1a). The plot based on the interactive model (Figure 1b) shows departure from being parallel (i.e., constant adjusted Hazard Ratio) which was confirmed with the significant interaction between BMI levels and WBC (p-value=0.0137). The fact that the line for BMI ≥35 lies above the line for BMI<35 showed that the adjusted HR for BMI≥35 was greater than the adjusted HR for BMI<35 and this was confirmed for total WBC counts of greater than 5. The estimated adjusted HR for WBC in the model with no interaction after adjusting for the effect of BMI and the other diabetes risk factors was 1.09 [95% CI (0.97, 1.24)]. In the interactive model WBC was associated with progression to diabetes in participants with BMI ≥35 and the estimated adjusted HR was 1.49 [95%CI (1.20, 1.85)] while WBC was not significantly associated with progression to diabetes in participants with BMI<35 and the estimated adjusted HR was 1.09 [95%CI (0.97, 1.85)]. Similarly, Figure 2a and 2b with two non-parallel lines present the HRs of granulocytes and lymphocytes respectively by the levels of BMI under the models with interaction, adjusting for the effect of age at the time of the event or censoring, gender, smoking, and triglycerides and stratified by family history of diabetes and pre-diabetes status by including strata statement in SAS Proc Phreg. Finally, Figure 2c presents the interaction effect between monocytes and BMI in relation to time to progression to type 2 diabetes and it shows that when monocytes were between 0 and 0.4, and 0.8 and 1.1 the HR lines for BMI≥35 and BMI<35 are approximately parallel, and the interaction effect between the two variables was not statistically significant (p-value=0.16).

The results from stratified analyses with multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models by BMI categories are reported in Table 5 which, are similar to those of the adjusted interactive models in Table 4. The results in Table 5 reconfirm that the significant associations of total WBC counts, lymphocytes and granulocytes with progression to type 2 diabetes were only among participants with BMI≥35. Furthermore, the stratum specific HR estimates for each of the variables in Table 5 were not similar indicating the presence of interaction effects of BMI with total WBC counts, lymphocytes and granulocytes.

Discussion

In this paper we have demonstrated that a majority of epidemiologist and scientists do not report whether they have explored potential interactive effects when reporting their findings in publications that involve regression analysis. We have also examined the adverse effects of ignoring interactions when using a Cox proportional hazards regression model. We used simulation studies and data from the Cameron County Hispanic Cohort, to demonstrate detection, calculation of effects based on interactive models, and graphical presentation of interactive effects. The approach for the simulation studies was to first generate data from an additive model with known distributions and apply an additive (without their product term) Cox proportional hazards regression model with two covariates x1 and x2 to estimate the regression parameters. In this scenario the relationship between the variable x1 and the time to event did not depend on the values of variable x2. Therefore in the perfect additive Cox proportional hazards regression model the inclusion of the interaction of the two covariates did not have a significant impact on main effects of regression coefficients estimates, hence on the estimated hazard ratios and their interpretation. In the second scenario data were generated using Cox proportional hazards regression model with two covariates x1 and x2 and their product term (Model 2). The analyses demonstrated that the misspecified models with no interaction term resulted with biased regression coefficient estimates, hence erroneous interpretations. In the interactive model the effect of x1 on time to event was dependent on the levels of variable x2 and we demonstrated how to calculate the adjusted HRs in the presence of interactions between x1 and x2.

Since this study focused on recognition of statistical interaction in regression analysis, in this paper we do not fully discus the findings from the CCHC data. However, the results from the CCHC prospective cohort study demonstrated with real life variables the difference between models with and without interaction term, more specifically the improvement of the inferences for hazard ratios for total WBC counts, granulocytes and lymphocytes after testing and identifying their interaction with dichotomous BMI ( BMI≥35 vs. BMI<35). The models with interaction terms revealed that WBC counts, lymphocyte and granulocyte were significant risk factors in the subjects with BMI ≥35. The presence of the interaction effects and the positive statistical association between total WBC counts, granulocytes and lymphocytes and progression to diabetes in individuals with BMI≥35 were confirmed when Cox proportional hazards regression models fitted separately in the BMI strata. Stratification is not only a technique to evaluate the presence of possible confounding but also allows for an evaluation of possible presence of interaction effect [1,2].

A key underlying assumption (assumption of proportional hazards) of the Cox proportional hazards model is that the hazard ratio is constant over time [1,18]. In our simulation studies and in the CCHC study the interactive variables met the proportional hazards assumption. However, stratification by the variable where this assumption does not hold is a popular solution to the problem by including strata statement in SAS Proc Phreg.

Strengths and Limitations

With the analyses of the simulated datasets and CCHC data we highlighted that failure to test for interaction effects in a regression analysis does lead to a significant bias in parameter estimates due to unaccounted interaction effect when it actually exists. We have also demonstrated calculation and interpretation of effects based on parameters estimates in a Cox regression models with a significant interactive effect. Statistical guidelines for best practices recommend assessment of interactions as one of the steps during the model building process [17,19]. Although the work presented here is based on Cox regression models, the findings from this study are generalizable to other regression models including linear, logistic, Poisson, and Negative binomial regression models.

Our studies have some limitations. These studies illustrated a two-way interaction effect between a continuous and a dichotomous variable. However in practice interaction effect may occur between continuous or categorical variables and it may even be represented by a higher order product terms. In addition in the Cox regression models to handle non-proportional hazards we used stratification in the variable where non-proportional hazards assumption was not met. However another method to handle non-proportional hazards is adding an interaction term between some function of time variable and the covariate which takes into consideration the non-constant influence of covariate on the hazard [20].

Since the main purpose of the study was to demonstrate the adverse effects of ignoring statistical interactions in regression models used in epidemiologic studies we did not use the developed sampling weights from the CCHC which were created to account for imbalances in the distribution of sex and age due to unequal participation of household members in the census tracts and to scale the sample to the population [21].

Conclusions

Our findings from a non-systematic review for this study revealed that a majority of published literature on epidemiologic studies that used multivariable regression models have not mentioned anything related to testing for statistical interactions, effect modification, or heterogeneity of effect. Although calculation and interpretation of interactive effects are more difficult these are essential if the effects are interactive or synergic. We recommend inclusion of interaction terms that are clinically significant even if the interaction effects are not statistically significant. The failure to identify interactive effects in regression models could lead to significant bias, misinterpretation of the results, and in some instances to incorrect public health interventions with potential adverse implications.

Acknowledgments

Part of this work was supported by the Center for Clinical and Translational Sciences, which is funded by National institutes of Health Clinical and Translational Award UL1 TR000371 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences or the National Institutes of Health.

Acknowledgements

Research idea and study design: KPV, MHR, JBM; data acquisition: JBM; statistical analysis/interpretation: KPV; wrote the manuscript: KPV; reviewed/edited manuscript: MHR, ML, JBM. Each author: provided intellectual content; contributed significantly to the preparation and/or revision of the manuscript; and approved the final version of the manuscript. KPV takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

References

- Kleinbaum DG, Kupper LL, Nizam A, Muller KE (2008) Applied Regression Analysis and Other Multivariable Methods. (4thedn), Duxbury Press.

- Szklo M, Nieto F (2007) Epidemiology: Beyond the Basics (2ndedn), Jones and Bartlett Publishers, Sudbury, MA.

- Gautier A, Roussel R (2010) Increases in Waist circumference and weight as predictors of type 2 diabetes in individuals with impaired fasting glucose: influence of baseline BMI. Diabetes care 33: 1850–1852.

- Hanai K, Babazono T, Takagi M, Yoshida N, Nyumura I et al. (2014) Obesity as an effect modifier of the association between leptin and diabetic kidney disease. J Diabetes Investig 5: 213-220.

- Derakhshan A, Sardarinia M, Khalili D, Momenan AA, Azizi F et al. (2014) Sex specific incidence rates of type 2 diabetes and its risk factors over 9 years of follow-up: Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study. PLoS One 9: e102563.

- Verhagen SN, Wassink AM, van der Graaf Y, Visseren FL, SMART Study Group (2013) C-reactive protein and incident diabetes in patients with arterial disease. Eur J Clin Invest 43: 1052-1059.

- Peters TJ (2008) Multifarious terminology: multivariable or multivariate? univariable or univariate?. PaediatrPerinatEpidemiol 22: 506.

- Vatcheva KP, Fisher-Hoch SP, Rahbar MH, Lee M, Olvera RL et al. (2015) Association of total and differential white blood cell counts to development of type 2 diabetes in Mexican Americans in Cameron County Hispanic Cohort. Diabetes Res Open J 1: 103-112.

- Bender R, Augustin T, Blettner M (2005) Generating survival times to simulate Cox proportional hazards models. Statistics in Medicine 24: 1713–1723.

- Burton A, Altman DG, Royston P, Holder RL (2006) The design of simulation studies in medical statistics. Statist Med 25: 4279-4292.

- Wicklin R Simulating data with SAS (2013) SAS Institute Inc., Cary NC, USA.

- Kleinman K, Horton JN (2014) SAS and R data management, statistical analysis and Grpahs. (2ndedn) Taylor&Francis Group, LLC.

- STATA. StataCorp. (2011) Stata Statistical Software: Release 12. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP.

- Crowther MJ, Lambert PC (2012) Simulating complex survival data. The Stata Journal 12: 674–687.

- Crowther MJ (2011) SURVSIM: Stata Module to Simulate Complex Survival Data, Statistical Software Components. Boston College Department of Economics: Boston.

- Allison PD (1977) Testing for Interaction in Multiple Regression. American Journal of Sociology 83: 144-153.

- Hosmer D, Lemeshow S (1999) Applied survival analysis. Regression modeling time to event data, New York.

- Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S (2000) Applied logistic regression. (2ndedn), John Wiley& Sons, Inc.

- Fisher-Hoch SP, Rentfro AR, Salinas J, Perez A, Brown HS, et al. (2010) Socioeconomic status and prevalence of obesity and diabetes in a Mexican American community, Cameron County, Texas, 2004-2007. Prev Chronic Dis 7: A53.

- Hansen T, Ahlström H, Söderberg S, Hulthe J, Wikström J, et al. (2009)

Citation: Vatcheva KP, Lee M, McCormick JB, Rahbar MH (2016) The Effect of Ignoring Statistical Interactions in Regression Analyses Conducted in Epidemiologic Studies: An Example with Survival Analysis Using Cox Proportional Hazards Regression Model. Epidemiol 6: 216. DOI: 10.4172/2161-1165.1000216

Copyright: © 2016 Vatcheva KP, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 14932

- [From(publication date): 2-2016 - Aug 25, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 13818

- PDF downloads: 1114