Research Article

Comparison of Caffeine and d-amphetamine in Cocaine-Dependent Subjects: Differential Outcomes on Subjective and Cardiovascular Effects, Reward Learning, and Salivary Paraxanthine

Scott D Lane1*, Charles E Green1, Joy M Schmitz1, Nuvan Rathnayaka1, Wendy B Fang2, Sergi Ferré3 and Gerard Moeller F41Center for Neurobehavioral Research on Addictions, Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences, University of Texas Health Science Center – Houston, Houston, TX USA

2Center for Human Toxicology, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, USA

3Integrative Neurobiology, Intramural Research Program, National Institute on Drug Abuse, Baltimore, MD, USA

4Division on Addictions, Department of Psychiatry, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, USA

- Corresponding Author:

- Scott D. Lane

Center for Neurobehavioral Research on Addictions

Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences, 1941 East Road

University of Texas Health Science Center – Houston, Houston, TX USA

Tel: (713) 486-2535

E-mail: scott.d.lane@uth.tmc.edu

Received date: January 03, 2014; Accepted date: February 27, 2014; Published date: March 06, 2014

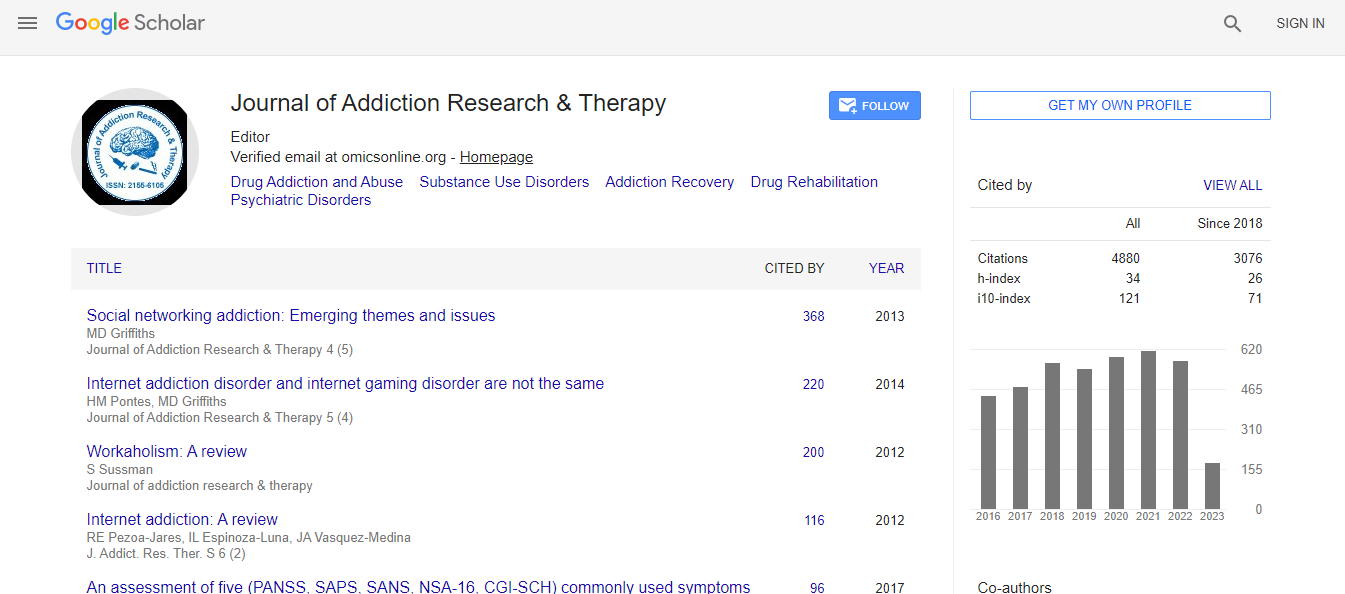

Citation: Lane SD, Green CE, Schmitz JM, Rathnayaka N, Fang WB, et al. (2014) Comparison of Caffeine and d-amphetamine in Cocaine-Dependent Subjects: Differential Outcomes on Subjective and Cardiovascular Effects, Reward Learning, and Salivary Paraxanthine. J Addict Res Ther 5:176. doi:10.4172/2155-6105.1000176Copyright: © 2014 Lane SD, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Due to indirect modulation of dopamine transmission, adenosine receptor antagonists may be useful in either treating cocaine use or improving disrupted cognitive-behavioral functions associated with chronic cocaine use. To compare and contrast the stimulant effects of adenosine antagonism to direct dopamine stimulation, we administered 150 mg and 300 mg caffeine, 20 mg amphetamine, and placebo to cocaine-dependent vs. healthy control subjects, matched on moderate caffeine use. Data were obtained on measures of cardiovascular effects, subjective drug effects (ARCI, VAS, DEQ), and a probabilistic reward-learning task sensitive to dopamine modulation. Levels of salivary caffeine and the primary caffeine metabolite paraxanthine were obtained on placebo and caffeine dosing days. Cardiovascular results revealed main effects of dose for diastolic blood pressure and heart rate; follow up tests showed that controls were most sensitive to 300 mg caffeine and 20 mg amphetamine; cocaine-dependent subjects were sensitive only to 300 mg caffeine. Subjective effects results revealed dose x time and dose x group interactions on the ARCI A, ARCI LSD, and VAS ‘elated’ scales; follow up tests did not show systematic differences between groups with regard to caffeine or d-amphetamine. Large between-group differences in salivary paraxanthine (but not salivary caffeine) levels were obtained under both caffeine doses. The cocainedependent group expressed significantly higher paraxanthine levels than controls under 150 mg and 3-4 fold greater levels under 300 mg at 90 min and 150 min post caffeine dose. However, these differences also covaried with cigarette smoking status (not balanced between groups), and nicotine smoking is known to alter caffeine/ paraxanthine metabolism via cytochrome P450 enzymes. These preliminary data raise the possibility that adenosine antagonists may affect cocaine-dependent and non-dependent subjects differently. In conjunction with previous preclinical and human studies, the data suggest that adenosine 2A modulating drugs may have value in the treatment of stimulant use disorders.

Spanish

Spanish  Chinese

Chinese  Russian

Russian  German

German  French

French  Japanese

Japanese  Portuguese

Portuguese  Hindi

Hindi