Research Article Open Access

Effect of a Web-based Health Risk Assessment with Tailored Feedback on Lifestyle among Voluntary Participating Employees: A Long-term Followup Study

Ersen B Colkesen1,2*, Eva K Laan1,2, Jan GP Tijssen1, Roderik A Kraaijenhagen2, Coenraad K van Kalken2 and Ron JG Peters1

1Department of Cardiology, Academic Medical Center - University of Amsterdam, P.O. Box 22660, 1100 DD, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

2NDDO Institute for Prevention and Early Diagnostics (NIPED), Amsteldijk 194, 1079 LK Amsterdam, The Netherlands

- *Corresponding Author:

- Ersen B Colkesen

Department of Cardiology

Academic Medical Center - University of Amsterdam

P.O. Box 22660, 1100 DD

Amsterdam, The Netherlands

E-mail: b.e.colkesen@amc.uva.nl

Received date March 23, 2013; Accepted date: April 15, 2013; Published date: April 18, 2013

Citation: Colkesen EB, Laan EK, Tijssen JGP, Kraaijenhagen RA, van Kalken CK, et al. (2013) Effect of a Web-based Health Risk Assessment with Tailored Feedback on Lifestyle among Voluntary Participating Employees: A Long-term Follow-up Study. J Community Med Health Educ 3:204. doi:10.4172/2161-0711.1000204

Copyright: © 2013 Colkesen EB, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Community Medicine & Health Education

Abstract

Background: Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD) by means of web-based Health Risk Assessment (HRA) with tailored feedback for individual health promotion is promising. We evaluated the effects on lifestyle of such a HRA program among employees of a Dutch worksite. Methods: We conducted a prospective follow-up study among employees who voluntarily participated in a webbased HRA including tailored feedback, offered to them by their employer. The program includes a multi-component HRA through a web-based electronic questionnaire, biometrics and laboratory evaluation. Results are combined with health behavior change theory to generate tailored motivating and educating health recommendations. Upon request, a health counseling session with the program physician is available. Follow-up data on lifestyle were collected one year after initial participation. Primary outcomes were the changes relative to baseline in proportions meeting recommendations for physical activity, fruit and vegetable intake, smoking and alcohol consumption. We checked for a possible background effect of an increased health consciousness as a consequence of program introduction at the worksite by comparing baseline measurements of early program participants with baseline measurements of participants who completed the program a year later. Results: A total of 142 employees completed follow-up measurements after mean 15 months. The proportion with a total physical activity amount of ≥ 150 minutes/week increased from 46% to 71% (p<0.001). The proportion with a physical activity pattern according to local recommendation (at least 30 minutes of moderate intensity physical activity on at least five days a week) was not increased. No differences were found in the proportions meeting recommendations for daily intake of fruit and vegetables, of moderate alcohol consumption, and smoking cessation. Changes were not explained by additional health counseling or increased health consciousness within the company. Conclusions: Among employees who voluntarily participated in a web-based HRA with tailored feedback the proportion with a total physical activity of ≥ 150 minutes/week increased by 25%. Web-based HRA programs with tailored feedback could help employers to enhance employee physical activity.

Keywords

Moderate intensity; Physical activity; Questionnaire; Biometrics

Background

Physical inactivity, smoking, excessive alcohol intake and unhealthy diet are important contributors to CVD morbidity and mortality risk [1,2]. Much of the CVD burden could be eliminated by primary prevention programs addressing these adverse lifestyles [3]. The Health Risk Assessment (HRA) is one of the most widely used strategies for primary prevention of CVD. The worksite has been proposed as a suitable platform for such programs, with the advantage of cost savings, the creation of a health-conscious environment and easier follow-up of high-risk individuals [4,5].

The traditional HRA predominantly screens for risk factors to produce an individual health risk profile and contains feedback that includes information regarding personal risk factor levels as compared to the general population [6]. However, reviews of the literature did not always support effectiveness of the traditional HRA [6,7]. It was theorized that HRA with feedback that merely contains risk information would be insufficient to promote health [8]. Furthermore, the impact of the traditional HRA remained unsatisfying as a consequence of suboptimal delivery due to resource constraints, limited access to high risk populations and lack in uniformity [6,7]. It was acknowledged that HRA programs could be enhanced to increase awareness of risk and affect health-behavior change, by web-based delivery and with incorporation of tailored health recommendations [8-11].

This study evaluates the long-term effects on lifestyle among employees who voluntarily participated in a web-based HRA including tailored feedback, offered to them by their employer as part of a worksite health management program. The HRA was designed to collect data that are necessary to screen for the risk of a number of preventable diseases, including CVD, and provide tailored feedback to educate, motivate and empower participants in CVD risk reduction. The primary aim was to measure whether lifestyle parameters were improved after participation in the program at a Dutch worksite.

Methods

Study groups and design

This prospective follow-up study was conducted at a single worksite of an information technology company in the Netherlands. During the study 2245 employees were invited to participate in a web-based HRA with tailored feedback. They were informed that their participation was being requested on a voluntary basis, that all personal data and health outcomes would be treated confidentially and that no individual results would be shared with their employer or any other third party.

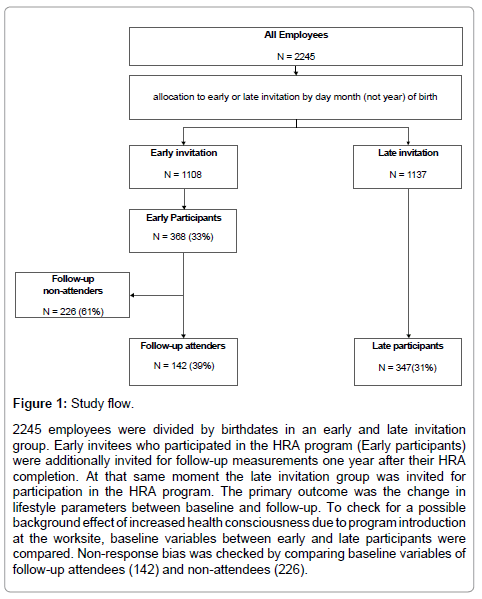

Before invitation employees were divided in an early (n=1108) and late (n=1137) invitation group, based on date (but not year) of birth (Figure 1). The early group was invited immediately to participate in the HRA program. Participants of the early group were re-invited to complete a lifestyle questionnaire one year after completing their initial HRA and receiving their individually tailored health recommendations, for follow-up data on lifestyle. They were not informed about followup until the moment of re-invitation. Employees of the late invitation group were invited one year after the early invitation group. Their baseline measurements were used to assess potential changes in lifestyle and risk factor levels as a consequence of company-wide changes in health-consciousness. If present, these changes would lead to overestimation of the effects of the HRA program. The study was approved as not needing ethics approval by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Academic Medical Center in Amsterdam.

Figure 1: Study flow.

2245 employees were divided by birthdates in an early and late invitation group. Early invitees who participated in the HRA program (Early participants) were additionally invited for follow-up measurements one year after their HRA completion. At that same moment the late invitation group was invited for participation in the HRA program. The primary outcome was the change in lifestyle parameters between baseline and follow-up. To check for a possible background effect of increased health consciousness due to program introduction at the worksite, baseline variables between early and late participants were compared. Non-response bias was checked by comparing baseline variables of follow-up attendees (142) and non-attendees (226).

Study intervention: Web-based health risk assessment with tailored feedback

A more detailed description of the study intervention is given in the Appendix. The studied program consists of 1) a multi-component web-based HRA and 2) individually tailored health recommendations, presented to participants as a web-based health plan. The HRA includes A) a web-based electronic questionnaire, B) biometric evaluation, and C) laboratory evaluation, targeting chronic disease risk, including CVD. Results of the assessment are translated in low, intermediate or highrisk profiles for the targeted disorders. By computer-based combination of the risk profiles with health-behavior concepts, individually tailored health recommendations are generated. Underlying healthbehavior concepts include the transtheoretical model [12], protection motivation theory [13], and social cognitive theory [14]. Generated health recommendations are presented to the participant integrated within a web-based health plan. Lifestyle recommendations within the health plan target physical activity, smoking cessation, dietary habits, stress management and alcohol intake. Upon request all participants can schedule a 30 minute health counseling session with the program physician after receiving their health plan. For participants at highrisk levels the health plans include referral for further evaluation and treatment. Risk factor cut-off values are based on the European and Dutch guidelines for cardiovascular risk management [15,16].

Baseline measurements

All participants completed the web-based electronic questionnaire as part of their HRA program. After accepting invitation they received a personal number for secure access to the questionnaire. The questionnaire included approximately 100 questions covering sociodemographics, family and personal health history, and lifestyle. Physical activity was measured with the Dutch version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) [17]. Both frequency (number of days a week) and duration (minutes) of moderate to vigorous physical activity were measured. In addition to the IPAQ questions, adherence to the Dutch Standard for Healthy Physical Activity was measured with one question on the number of days per week with at least 30 minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity. For adults, the recommendation is at least 30 minutes of moderate intensity physical activity -e.g. brisk walking, cycling, gardening-on at least five days a week, but preferably every day [18]. Dietary habits and alcohol consumption were measured according to the standard nutrition and alcohol consumption questionnaire of the Dutch Municipal Health Service [19]. Smoking behavior was measured with the Dutch Expert Center on Tobacco Control questionnaire [20]. For each lifestyle item the questionnaire collected constructs from the transtheoretical model, protection motivation theory, and social cognitive theory, including stage of change, self-efficacy, and motivation to change [12,21,22].

All early and late program participants visited the worksite occupational health service for measurement of height, weight, waist circumference and blood pressure. During the visit non-fasting blood and urine samples were collected for analysis of total cholesterol, LDLcholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, triglycerides, glucose, creatinin, and urinary albumin to creatinin ratio. All procedures were performed by trained nurses. Biometric and laboratory evaluation were not part of the follow-up measurements.

Follow-up questionnaire

The early participants were re-invited to complete a web-based follow-up lifestyle questionnaire one year after they completed their baseline HRA and received their web-based health plans with individually tailored health recommendations. Invitations were sent by e-mail with one reminder. The follow-up questionnaire assessed, identical to the baseline HRA questionnaire, physical activity, smoking status, alcohol consumption and daily fruit and vegetable intake.

Outcomes and data analysis

Primary outcomes were self-reported changes in lifestyle relative to baseline. For physical activity adherence to the Dutch Standard for Healthy Physical Activity and the total of 150 minutes or more of moderate to intensive physical activity per week (the product of the minimum frequency and duration of physical activity required by the Dutch Standard) were the outcomes. For fruit and vegetable intake outcomes were changes in a daily intake in accordance with the Dutch Health Council recommendations, i.e. at least 2 pieces of fruit and 3 to 4 serving spoons of vegetables daily [23]. For smoking behavior the outcome was the change in smoking status relative to baseline and for alcohol the change in excessive intake according to the Dutch Health Council recommendations, i.e. more than 21 units per week for men and more than 14 units per week for women [23]. McNemar’s test was used for comparison of the proportions showing positive change after participating in the HRA and receiving tailored feedback, compared with proportions showing negative change [24]. In addition, the proportions with positive change in lifestyle parameters were compared between participants who had a voluntary health counseling session additional to their web-based health plan and those who did not, using chi-squared tests.

Non-response bias was checked by comparing differences in baseline values between early participants who attended for followup measurements and those who did not, using unpaired t-test for continuous and chi-squared tests for dichotomous variables. These comparisons were adjusted for age and gender differences by linear and logistic regression analysis for continuous and dichotomous outcomes respectively. Finally, to account for potential changes as a consequence of company-wide changes in health-consciousness after program introduction, baseline values of early and late participants were compared. In these analyses unpaired t-test were used for continuous and chi-squared tests for dichotomous variables. Data were analyzed using SPSS 17 for Windows.

Results

Of the 1108 early invited employees, 368 (33%) participated in the web-based HRA program, compared to 347 (31%) of the 1137 late invited employees. Table 1 summarizes the baseline values of early participants who attended follow-up measurements and those who did not attend. Of the early group of 368 employees who completed the HRA program, 142 (39%) attended for follow-up measurements and 226 (61%) did not. Early participants who attended follow-up were older than those who did not (mean 47 vs. 43 years, p<0.001). There were no differences in physical activity, nutrition, smoking behavior and alcohol intake. Early participants who attended follow-up had a higher mean Framingham CVD risk score (10.7% vs. 7.7%, p<0.001) and had a higher mean systolic blood pressure (135.0 vs. 131.5 mmHg, p=0.04). After adjustment for sex and age, there were no statistically significant differences between early participants who attended for follow-up and those who did not attend.

| Early Participants (n=368) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With follow-up (n=142) | Without follow-up (n=226) | p† unadjusted | p† adjusted | |||

| Mean age (years) | 47 | ± 7.87 | 43 | ± 7.44 | <0.001 | - |

| Male sex | 116 | (82%) | 180 | (80%) | 0.63 | - |

| Education | ||||||

| low | 21 | (15%) | 16 | (7%) | 0.06 | 0.33 |

| midlevel | 38 | (27%) | 56 | (25%) | ||

| high | 83 | (58%) | 154 | (68%) | ||

| History of CVD | 6 | (4%) | 4 | (2%) | 0.16 | 0.39 |

| Current medication therapy for hypertension | 11 | (8%) | 18 | (8%) | 0.94 | 0.36 |

| Current statin use | 7 | (5%) | 12 | (5%) | 0.87 | 0.25 |

| Current diabetes medication | 2 | (1%) | 5 | (2%) | 0.58 | 0.39 |

| Physical activity | ||||||

| Adherence to Adherence to Dutch Standard for Healthy Physical Activity* | 34 | (24%) | 48 | (21%) | 0.54 | 0.95 |

| Total amount of moderate physical activity ≥150 minutes/week | 65 | (46%) | 108 | (48%) | 0.71 | 0.57 |

| Nutrition | ||||||

| Fruit : consumption of ≥ 2 pieces/day | 26 | (18%) | 47 | (21%) | 0.44 | 0.91 |

| Vegetables: consumption of ≥ 3 serving spoons (≥ 150 grams) per day | 61 | (43%) | 96 | (43%) | 0.53 | 0.52 |

| Smoking | ||||||

| Daily tobacco smoking | 23 | (16%) | 36 | (16%) | 0.95 | 0.77 |

| Alcohol consumption | ||||||

| men drinking >21 units/week or women drinking >14 units/week | 8 | (6%) | 17 | (8%) | 0.48 | 0.21 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 25.4 | ± 3.41 | 25.3 | ± 3.61 | 0.85 | 0.83 |

| BMI ≥ 25 | 69 | (49%) | 108 | (48%) | 0.88 | 0.81 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 93.0 | ± 11.01 | 92.5 | ± 10.31 | 0.67 | 0.90 |

| Waist circumference, men >102 cm, women >88 cm | 32 | (23%) | 50 | (22%) | 0.93 | 0.95 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure (mmHg) | 135.0 | ± 17.18 | 131.5 | ± 15.58 | 0.04 | 0.17 |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure (mmHg) | 81.8 | ± 11.05 | 79.7 | ± 10.47 | 0.07 | 0.26 |

| Blood pressure ≥ 140/90 (mmHg) | 55 | (39%) | 66 | (29%) | 0.06 | 0.26 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/l) | 5.7 | ± 1.04 | 5.6 | ± 0.92 | 0.12 | 0.42 |

| HDL (mmol/l) | 1.4 | ± 0.34 | 1.4 | ± 0.37 | 0.48 | 0.29 |

| LDL (mmol/l) | 3.7 | ± 0.90 | 3.5 | ± 0.86 | 0.08 | 0.25 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/l) | 1.6 | ± 0.98 | 1.5 | ± 0.85 | 0.26 | 0.41 |

| Framingham 10 year CVD risk score (%) | 10.7 | ± 8.84 | 7.7 | ± 6.66 | <0.001 | 0.19 |

Table 1: Baseline characteristics of 368 early participants in the HRA program by follow-up status.

*For adults at least half an hour of moderately intensive physical activity on at least five days a week is recommended. p†: P for difference between early participants with follow-up and without follow-up. Analyses for differences in baseline systolic and diastolic blood pressure, body mass index, waist circumference, total cholesterol, HDL, LDL, triglycerides and Framingham scores were adjusted for age and sex, using linear regression with the variable of interest as dependent variable and age, sex and attending for follow-up measurements as covariates. Analyses for differences in history of CVD, current medication for hypertension, current statin use, current diabetes medication, current smoking and blood pressure ≥ 140/90 mmHg were adjusted for age and sex, using logistic regression with the variable of interest as dependent variable and age, sex and attending for follow-up measurements as covariates.

Table 2 shows the change in lifestyle factors relative to baseline. The mean follow-up time was 15 months. The proportion adhering to the Dutch Standard for Healthy Physical Activity increased from 24% to 29% (p=0.25), whereas the proportion with a total amount of physical activity of >150 minutes per week increased from 46% to 71% (p<0.001). The total amount of physical activity increased by 84 minutes per week (95% CI 45 to 122, p<0.001, data not shown). The proportion that complied with the daily fruit intake norm increased from 18% to 25% (p=0.06). There were no changes in the proportions with a daily vegetable intake of 3 or more serving spoons and no or moderate alcohol intake. The proportion of non-smokers decreased due to relapse after quitting in four cases with from 84% to 82% (p=0.38). Forty of the 142 follow-up attendees had a voluntary health counseling session in addition to their web-based health plans. There were no statistically significant differences in the proportions with positive change between these 40 follow-up attendees and the 102 who did not have had a health counseling session in addition to their webbased health plans (data not shown).

| Status at baseline (n=142) | Status at follow-up (n=142) | positive change | negative change | p | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical activity | |||||||||

| Adherence to Dutch Standard for Healthy Physical Activity* | 34 | (24%) | 41 | (29%) | 17 | (12%) | 10 | (7%) | 0.25 |

| Total amount of moderate physical activity ≥150 minutes/week | 65 | (46%) | 101 | (71%) | 49 | (35%) | 13 | (9%) | < 0.001 |

| Nutrition | |||||||||

| Fruit : consumption of ≥2 pieces/day | 26 | (18%) | 36 | (25%) | 17 | (12%) | 7 | (5%) | 0.06 |

| Vegetables: consumption of ≥ 3 serving spoons (≥ 150 grams) per day | 61 | (43%) | 61 | (43%) | 16 | (11%) | 16 | (11%) | 1.00 |

| Tobacco smoking | |||||||||

| Non smokers | 119 | (84%) | 116 | (82%) | 1 | (1%) | 4 | (3%) | 0.38 |

| Alcohol consumption | |||||||||

| No or moderate alcohol consumption† | 134 | (94%) | 134 | (94%) | 3 | (2%) | 3 | (2%) | 1.00 |

Table 2: Changes in lifestyle of 142 early HRA program participants, who attended follow-up measurements at 15 months.

*For adults at least half an hour of moderately intensive physical activity on at least five days a week is recommended. † No or moderate alcohol consumption is defined as: men drinking < 21 units/week or women drinking < 14 units/week p: McNemar for the difference between positive change and negative change.

Table 3 summarizes baseline values between early and late participants. Early and late participants were similar in demographics, lifestyle and health status. Diastolic blood pressure of late participants was 1.8 mmHg lower. Framingham risk scores were however similar between early and late participants. Late participants had a 0.7 kg/m2 greater body mass index and a 2 centimeter greater waist circumference. Furthermore, late participants had 0.3 mmol/l higher total cholesterol, a 0.2 mmol/l higher LDL-cholesterol and 0.1 mmol/l higher triglycerides.

| Early participants (n=368) | Late participants (n=347) | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (years) | 45 | ± 7.79 | 44 | ± 8.12 | 0.30 |

| Male sex | 296 | (80%) | 281 | (81%) | 0.85 |

| Education | |||||

| low | 37 | (10%) | 25 | (7%) | 0.25 |

| midlevel | 94 | (26%) | 84 | (24%) | |

| high | 237 | (64%) | 238 | (69%) | |

| History of CVD | 10 | (3%) | 9 | (3%) | 0.92 |

| Current medication therapy for hypertension | 29 | (8%) | 26 | (7%) | 0.85 |

| Current statin use | 19 | (5%) | 17 | (5%) | 0.87 |

| Current diabetes medication | 7 | (2%) | 4 | (1%) | 0.42 |

| Physical activity | |||||

| Adherence to Dutch Standard for Healthy Physical Activity* | 82 | (22%) | 78 | (23%) | 0.95 |

| Total amount of moderate physical activity ≥150 minutes/week | 173 | (47%) | 168 | (48%) | 0.71 |

| Nutrition | |||||

| Fruit : consumption of ≥ 2 pieces/day | 73 | (20%) | 58 | (17%) | 0.48 |

| Vegetables: consumption of ≥ 3 serving spoons (≥ 150 grams) per day | 157 | (43%) | 132 | (38%) | 0.38 |

| Smoking | |||||

| Daily tobacco smoking | 59 | (16%) | 52 | (15%) | 0.70 |

| Alcohol consumption | |||||

| men drinking >21 units/week or women drinking >14 units/week | 25 | (7%) | 25 | (7%) | 0.43 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 25.3 | ± 3.53 | 26.0 | ± 3.69 | 0.01 |

| BMI ≥ 25 | 177 | (48%) | 192 | (55%) | 0.05 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 92.7 | ± 10.57 | 94.7 | ± 11.69 | 0.02 |

| Waist circumference, men >102 cm, women >88 cm | 82 | (22%) | 102 | (29%) | 0.02 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure (mmHg) | 132.9 | ± 16.29 | 132.9 | ± 15.48 | 0.97 |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure (mmHg) | 80.5 | ± 10.73 | 78.7 | ± 9.68 | 0.02 |

| Blood pressure ≥ 140/90 mmHg | 121 | (33%) | 115 | (33%) | 0.47 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/l) | 5.6 | ± 0.97 | 5.9 | ± 1.04 | <0.001 |

| HDL (mmol/l) | 1.4 | ± 0.36 | 1.5 | ± 0.41 | 0.08 |

| LDL (mmol/l) | 3.6 | ± 0.88 | 3.8 | ± 0.98 | 0.001 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/l) | 1.6 | ± 0.90 | 1.7 | ± 0.95 | 0.04 |

| Framingham 10 year CVD risk score (%) | 9.4 | ± 8.04 | 9.6 | ± 7.29 | 0.73 |

Table 3: Comparison of baseline values between early and late participants in the HRA program.

*For adults at least half an hour of moderately intensive physical activity on at least five days a week is recommended. p: p for difference in baseline value between ‘early participants’ and ‘late participants’ for time trend analysis.

Discussion

This study evaluated the long-term changes in lifestyle among employees at a Dutch worksite, who voluntarily completed a web-based HRA and received tailored health recommendations. We observed a significant increase in the proportion with a total physical activity amount of >150 minutes/week by 25%, whereas the proportion with a physical activity pattern according to the Dutch Standard for Healthy Physical Activity (at least 30 minutes of moderate intensity physical activity on at least five days a week) was not significantly improved. We found no statistically significant changes in other lifestyle parameters no additional benefit of voluntary health counseling in addition to the web-based health recommendations.

Studies focusing on health-behavior change with computerdelivered interventions show great variability due to heterogeneity and complexity of studied programs, as well as their populations and their evaluation [25]. A recent meta-analysis of 75 randomized controlled trials of computer-delivered interventions for health promotion, showed immediate post-intervention improvements in health-related knowledge, attitudes and intentions, but not in behavioral outcomes like physical activity [26]. Included studies, however, insufficiently addressed the effect of tailoring on health-behavior change. Studies on the effectiveness of computer-tailored education have shown that computer-delivered health recommendations that directly matched individual risk, motivation for health-behavior change, and selfefficacy may increase physical activity levels [27]. It is thus important to tailor health recommendations to the unique cognitions, needs, preferences and concerns of the individual, to realize effective health communication [28,29]. In this study the health recommendations were tailored based on an integrated health risk profile. Furthermore, principles from different health behavior theories were used for the content, the structuring and the tailoring of the health recommendations (Appendix I).

Interestingly, we found no additional benefit of voluntary health counseling in addition to the web-based tailored health recommendations. This is in line with a recent cohort-randomized trial that reported favorable changes in CVD risk factors, most of which were achieved with worksite health assessments in the absence of counseling or other interventions [30]. The significance of this finding is that worksites which lack resources to offer additional health counseling may opt for an HRA with tailored health recommendations only program.

The proportion with a total physical activity amount of ≥ 150 minutes/week increased by 25%, whereas the proportion meeting the Dutch guideline requirements (i.e. at least 30 minutes of moderate intensity physical activity on at least five days a week) was improved by 5%, which was not statistically significant. This suggests that participants improved their overall physical activity amount in minutes, but not the frequency over the week. An explanation for this finding could be that improving physical activity over five times a week was not feasible or at least not practical in this population of highly educated employees, and that employees were indeed motivated and improved their physical activity in exercise sessions less than 5 times a week. This finding is addressed in the recent 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, stating that existing scientific evidence does not demonstrate superiority of 30 minutes on 5 days a week compared to an accumulation of 150 minutes over the week, and therefore individuals are allowed to accumulate 150 minutes a week in various ways [31]. A recent consensus statement from the British Association of Sport and Exercise Sciences includes similar conclusions, stating that all healthy adults should aim to take part in at least 150 min of moderate-intensity activity each week, or at least 75 min of vigorousintensity aerobic activity per week, or equivalent combinations of moderate- and vigorous-intensity activities [32]. To stimulate physical activity in general, the current Dutch Standard for Healthy Physical Activity could be reconsidered in this way.

For other lifestyle variables we observed no statistically significant changes. Regarding healthy nutrition, in our study only fruit and vegetable intake were measured for practical reasons, whereas the health recommendations for healthy nutrition in the studied HRA program address the whole nutrition spectrum and provide alternatives for fruit and vegetable intake, e.g. fruit drinks and vitamin preparations. Consequently, participants may have changed their dietary habits in ways that were not measured in this study. Alcohol consumption was not reduced. The proportion that had excessive intake was however small and the need for change consequently limited. The increase in the proportion of daily smokers was due to relapse in four cases after quitting. Although this increase is non-significant the program apparently did not sufficiently motivate these participants to continue quitting.

The design of our study enabled us to check for a possible background effect of an increased health consciousness as a consequence of program introduction at the worksite. We found that mean diastolic blood pressure was lower among late participants when compared to early participants. This suggests a background effect of an increased health consciousness within the company, possibly as a consequence of program introduction. However, the mean overall CVD risk score was the same. Moreover, body mass index, waist circumference and lipid profiles of late participants were higher compared to early participants. Therefore, although we cannot completely rule out a background effect, its magnitude is marginal.

Our study has several limitations. First, participation in the studied HRA program was voluntary, with participation rates of 33% among the early participants and 31% among the late participants. Studies that evaluated HRA or health promotion programs reported participation rates from 20% to 76%, [33,34] with the general impression that females, older employees, and mainly the worried well are attracted [35]. Although the participation rate in this study lies in the range of expected, we cannot rule out that among non-participants in the HRA program there were employees with more or less favorable health characteristics. Furthermore, of the early participants who were eligible for study measurements 39% completed follow-up. However, after adjustment for differences in age and gender, there were no differences between follow-up attendees and non-attendees. Therefore, the outcomes of our study are valid among employees who voluntarily participated in the HRA program. Second, ideally changes in lifestyle parameters in late participants would also have been measured a year before the beginning of their program. In this way their measurements could have served as a rigorous control for early participants. Unfortunately we were not able to do an early measurement in late participants. However, the absence of a clinically relevant background effect support that differences observed among early participants may be attributed to completion of the HRA program. Third, changes in lifestyle were self-reported and consequently prone to social desirability bias. Self-report measures should be interpreted with caution when used to evaluate changes in lifestyle. In this study both baseline and follow-up questionnaires were equally prone to this bias. Therefore observed changes in physical activity may be considered relevant. Finally, participants in the program were pre-dominantly well educated male employees of a single worksite. Therefore our findings may be applicable only to similar populations.

Conclusions

Among employees who voluntarily participated in a web-based HRA with tailored feedback the proportion with a total physical activity of ≥150 minutes/week was increased by 25% at 15 months. The proportion meeting local guideline recommendation of at least 30 minutes of moderate intensity physical activity on at least five days a week did not increase, suggesting that participants tended to increase their total amount of physical activity rather than the physical activity frequency over the week. No differences were found in proportions meeting recommendations on fruit and vegetable consumption, tobacco smoking, and alcohol consumption. Changes were not explained by additional health counseling or increased health consciousness within the company. Web-based HRA programs with tailored feedback could help employers to enhance employee physical activity. Further research with controlled trials is needed to determine whether findings are attributable to the intervention and to determine effect size.

Competing Interests

CVK and RAK are directors and co-owners of NIPED. This institute developed the studied program and currently markets it in the Netherlands. For the present study NIPED provided for a Ph.D. grant for EBC. During the study EKL was an intern at the research department of NIPED, where she worked on the current project as a research trainee. All other authors are employed by the Academic Medical Center at the University of Amsterdam. They received no additional funding for this study and report no competing interests.

Authors’ Contributions

RJP and JGT were the principal investigators of the study. They developed the concept and the design of the study and contributed to the interpretation of data. EBC and EKL carried out the subject recruitment, data collection and data analyses. EBC performed the main writing and statistical analyses. EBC and EKL drafted the manuscript. RAK and CKK participated in coordination of the study. All authors reviewed a previous version of the manuscript and vouch for the accuracy and completeness of the data and analyses.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the scientific advisory board of NIPED for their contribution in the development of the studied HRA program. We further thank all employees of the study worksite for their participation and enthusiasm.

References

- Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, Dans T, Avezum A, et al. (2004) Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet 364: 937-952.

- Preventing chronic diseases: a vital investment (2005): World Health Organization global report.

- Yach D, Hawkes C, Gould CL, Hofman KJ (2004) The global burden of chronic diseases: overcoming impediments to prevention and control. JAMA 291: 2616-2622.

- Carnethon M, Whitsel LP, Franklin BA, Kris-Etherton P, Milani R, et al. (2009) Worksite wellness programs for cardiovascular disease prevention: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 120: 1725-1741.

- Goetzel RZ, Ozminkowski RJ (2008) The health and cost benefits of work site health-promotion programs. Annu Rev Public Health 29: 303-323.

- Soler RE, Leeks KD, Razi S, Hopkins DP, Griffith M, et al. (2010) A systematic review of selected interventions for worksite health promotion. The assessment of health risks with feedback. Am J Prev Med 38: S237-262.

- Anderson DR, Staufacker MJ (1996) The impact of worksite-based health risk appraisal on health-related outcomes: a review of the literature. Am J Health Promot 10: 499-508.

- Cowdery JE, Suggs LS, Parker S (2007) Application of a Web-based tailored health risk assessment in a work-site population. Health Promot Pract 8: 88-95.

- Kreuter MW, Strecher VJ (1996) Do tailored behavior change messages enhance the effectiveness of health risk appraisal? Results from a randomized trial. Health Educ Res 11: 97-105.

- Kreuter MW, Strecher VJ, Glassman B (1999) One size does not fit all: the case for tailoring print materials. Ann Behav Med 21: 276-283.

- Noar SM, Benac CN, Harris MS (2007) Does tailoring matter? Meta-analytic review of tailored print health behavior change interventions. Psychol Bull 133: 673-693.

- Prochaska JO, Velicer WF (1997) The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot 12: 38-48.

- Floyd DL, Prentice-Dunn S, Rogers RW (2000) A Meta-Analysis of Research on Protection Motivation Theory. J Appl Soc Psychol 30: 407-429.

- Bandura A (1986) Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall

- Burgers JS, Simoons ML, Hoes AW, Stehouwer CD, Stalman WA (2007) Guideline 'Cardiovascular Risk Management'. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 151: 1068-1074.

- Graham I, Atar D, Borch-Johnsen K, Boysen G, Burell G, et al. (2007) European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: executive summary: Fourth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (Constituted by representatives of nine societies and by invited experts). Eur Heart J 28: 2375-2414.

- Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjöström M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, et al. (2003) International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc 35: 1381-1395.

- Kemper HCG, Ooijendijk WTM, Stiggelbout M (2000) Consensus regarding the Dutch norm of healthy activity. T Soc Geneesk 78: 180-183.

- Brink CL van den, Ocke MC, Houben AW, Nierop P van, Droomers M (2005) Validation of a Community Health Services food consumption questionnaire in the Netherlands. Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu RIVM. Ref Type: Report

- Mudde AN, Willemsen MC, Kremers S, De Vries H (2000) Meetinstrumenten voor onderzoek naar roken en stoppen met roken. [Measurements for research on smoking and smoking cessation]. Den Haag, STIVORO. Ref Type: Report

- Bandura A (1997) Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York, NY: WH Freeman & Co.

- Prochaska JO, Crimi P, Lapsanski D, Martel L, Reid P (1982) Self-change processes, self-efficacy and self-concept in relapse and maintenance of cessation of smoking. Psychol Rep 51: 983-990.

- Health Council of the Netherlands. Guidelines for a healthy diet 2006. 2006. Health Council of the Netherlands. Ref Type: Report

- Giuliano KK, Scott SS, Elliot S, Giuliano AJ (1999) Temperature measurement in critically ill orally intubated adults: a comparison of pulmonary artery core, tympanic, and oral methods. Crit Care Med 27: 2188-2193.

- Alter DA (2007) Therapeutic lifestyle and disease-management interventions: pushing the scientific envelope. CMAJ 177: 887-889.

- Portnoy DB, Scott-Sheldon LA, Johnson BT, Carey MP (2008) Computer-delivered interventions for health promotion and behavioral risk reduction: a meta-analysis of 75 randomized controlled trials, 1988-2007. Prev Med 47: 3-16.

- Kroeze W, Werkman A, Brug J (2006) A systematic review of randomized trials on the effectiveness of computer-tailored education on physical activity and dietary behaviors. Ann Behav Med 31: 205-223.

- Making Health Communications Work (1989) Washington, DC, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). 89-1493.

- Brug J, Glanz K, Van Assema P, Kok G, van Breukelen GJ (1998) The impact of computer-tailored feedback and iterative feedback on fat, fruit, and vegetable intake. Health Educ Behav 25: 517-531.

- Racette SB, Deusinger SS, Inman CL, Burlis TL, Highstein GR, et al. (2009) Worksite Opportunities for Wellness (WOW): effects on cardiovascular disease risk factors after 1 year. Prev Med 49: 108-114.

- Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans (2008) U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)

- O'Donovan G, Blazevich AJ, Boreham C, Cooper AR, Crank H, et al. (2010) The ABC of Physical Activity for Health: a consensus statement from the British Association of Sport and Exercise Sciences. J Sports Sci 28: 573-591.

- Dobbins TA, Simpson JM, Oldenburg B, Owen N, Harris D (1998) Who comes to a workplace health risk assessment? Int J Behav Med 5: 323-334.

- Robroek SJ, van Lenthe FJ, van Empelen P, Burdorf A (2009) Determinants of participation in worksite health promotion programmes: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 6: 26.

- Lerman Y, Shemer J (1996) Epidemiologic characteristics of participants and nonparticipants in health-promotion programs. J Occup Environ Med 38: 535-538.

Relevant Topics

- Addiction

- Adolescence

- Children Care

- Communicable Diseases

- Community Occupational Medicine

- Disorders and Treatments

- Education

- Infections

- Mental Health Education

- Mortality Rate

- Nutrition Education

- Occupational Therapy Education

- Population Health

- Prevalence

- Sexual Violence

- Social & Preventive Medicine

- Women's Healthcare

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 15607

- [From(publication date):

May-2013 - Dec 22, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 10891

- PDF downloads : 4716