Case Report Open Access

A Case Study "A Life with and beyond Cancer"

Jan Sitvast*University of Applied Sciences, Hogeschool Utrecht, Faculty of Health, Heidelberglaan 7, Utrecht, 3584CS, Netherlands

- *Corresponding Author:

- Sitvast J

Researcher, University of Applied Science, Hogeschool Utrecht, Faculty of Health

Heidelberglaan 7, Utrecht, 3584CS, Netherlands

Tel: 0031614328220

E-mail: Jan.sitvast@hu.nl

Received date: May 23, 2016; Accepted date: May 30, 2016; Published date: May 31, 2016

Citation: Sitvast J (2016) A Case Study "A Life with and beyond Cancer". J Palliat Care Med 6: 266. doi:10.4172/2165-7386.1000266

Copyright: © 2016 Sitvast J. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Palliative Care & Medicine

Abstract

Purpose: Developing an intervention with photography to support patients in their search for a meaningful and valued life with their disease.

Method: Pilot-testing a prototype of an intervention that had been developed for another target group. The research approach is a prototypical case study.

Results: Being photographed and being able to direct the kind of photographs helped the patient to reflect on her life with cancer, but also on her life beyond the disease.

Conclusions: The photographs mediated the patient’s story where otherwise words alone might not have been able to make sense of confused feelings. Nurses can look for creative ways to involve the patient and relevant others in the process of meaning giving as a first step in coping with the disease and its consequences.

Keywords

Hermeneutic photography; Meaning giving; coping; Psychosocial approach; Recovery

Introduction

The following report is a case study based on a pilot to test a new intervention for psychosocial recovery from cancer. The case report tells the story of one cancer patient and how she experienced the intervention. The setting is a hospital in a small provincial town in the eastern part of the Netherlands.

Recovering from a serious and potentially invalidating disease means to patients more than a physical process of cure alone. The impact of the disease on the daily life is often huge. Daily routines turn out not to be as self-evident as they seemed to be. Someone’s roles as a father/mother, brother/sister, and son/daughter assume a different quality in the light of the shown vulnerability. In the first place this is caused by the (temporarily) changed perspective on the future, but also through the care and concern from others. For the patient it is sometimes difficult to find her own way in these entangled feelings. It is a process in which she must give new meaning to her life. Going through a process of a disease leads often to moments of reflection, and arriving at a crossing point in life from where, after crises and desperation, one must find the way up again.

Background

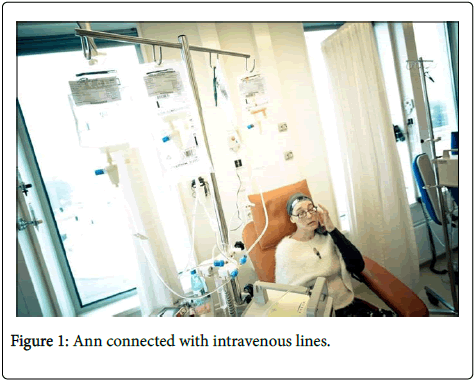

Notwithstanding the fact that in recent years treatment methods have enormously improved and with it the prognosis for survival, cancer is still seen as a life threatening disease and is associated with decay, suffering and death (Figure 1).

Patients notice that in their contacts with others. In the worst case contact with the patient is shunned. The most painful moment that this happens, is when the patient loses his/her hair because of the chemo treatment. The bald head signifies the cancer patient and is like a stigma that sets him/her apart from the other people who are not sick [1,2]. In the contact with other people this is a direct confrontation with the disease, in the first place for the patient him/herself when he looks into the mirror or when he/she sees the reaction in the eyes of the others. The other person cannot but react. Loss of hair cannot be overlooked neither looked away from. Hair has a great symbolical meaning and stands for youth, vitality and energy. In the biblical story of Samsom his long hair gave him extraordinary strength with which he terrorized the Jewish people. Delila found out his secret and cut his hair while he was asleep. Samsom then lost his powers and was conquered, so the story has it. The parallel with cancer may be that because of the chemo treatment patients lose their hair and feel vulnerable, being depleted of energy and being often very tired. Facing the disease they may feel powerless and afraid that it will overwhelm them.

That’s why we (the Sitvast and members of the project team) developed an intervention (with photography playing an important role in it) to support patients in their search for a meaningful and valued life with their disease. This use of the medium of photography is called ‘hermeneutic photography’ [3-6] which is part of a growing interest in how to apply photographs as a therapeutic intervention [7].

By chance we came into contact with Ann (pseudonym), who was a patient at the local hospital and, with a good prognosis, recovering from breast cancer. She approached the photographer in the project team and they agreed that he would follow her and photograph her during her recovery and treatment. We were invited to work together with her and see how her photographs could help her to tell her story. We modelled the intervention after a similar intervention in mental health care [8] and called the newly developed intervention: ‘Just Look At Her/Hair! (in Dutch her and hair have an identical spelling: Haar) A life with and beyond cancer’ referring to the person (her) and to hair.

Purpose of the Case Study

Our intention was to pilot-test the intervention before it comes available for other patients with cancer who also receive a treatment from an oncology department or clinic in a hospital. By photographing them we want to portray and support them in their search for what they consider valuable in their lives, that what inspires them and gives them joy of living and eventually the strength to recover from their disease (not necessarily synonym to cure). This is a therapeutic goal, but we also aim at a better understanding from the general public. In this way it will contribute to a more sensitive communication between the ill and the healthy, leading may-be to a situation that patients receive more comprehension and support.

Methods

Case studies are often used as a research strategy in a process of designing new interventions and policy measures [8]. They are then called prototypical case studies. Case studies are done in fundamental academic research as well as in practice oriented research. The latter is the case with the study in this article. The most important criterion to distinguish practice oriented research from fundamental research can be found in the utility of its findings for future users of the intervention. In this respect the case serves us to provide insight into an issue. The issue involved here is the question: does the intervention help patients to find meaning and strength to recover from their disease? The case study is instrumental to that aim. Having formulated a topical concern, the researcher may pose “foreshadowed problems” [9] that will also be studied in the case. These are the (sub) themes or issues that have been translated into research questions. They are formulated here.

Themes or issues and their related research questions

Photography is deployed in the search for meaning. Meaning giving is not only a cognitive activity, but much more an expression of vitality, as ‘having (again) a mind/fancy for’, so being able to enjoy, experience happiness and satisfaction. Remembering and becoming aware of important values in life and pleasant things to do will contribute to more resilience and eventually facilitate the process of recovery from cancer. During the photography sessions the search for inspiration will be carried out as the patient goes along. We assume that the action of making photographs and the pictures themselves are building stones in a trajectory during which the patient reflects on his life with cancer, but also on his life beyond the disease. The photographs facilitate a conversation that the patient has with him/herself.

Research question: Do the photographs facilitate this process of reflection and value finding?

Learning to deal with different self-portraits can help someone to accept that our experiences are often complex and multi-layered. Instead of only being able to see ‘faults’ and ‘the thing that went wrong’ (wronging ourselves unnecessarily) it is possible to reconciliate ourselves with the different aspects that make up the whole of the persons who we are and which can be told by photo portraits. This ‘wholeness’ is a visual thing to a large degree and therefore can be expressed and experienced in self-portraits. Being able to experience the good about oneself as reflected in the photo portrait makes it easier to face also the ‘broken’ and ‘wounded’ facets of oneself [5,10,11] as for instance the bald head due to the chemo, the breast amputation by surgery or the stoma after an intestinal operation. The ultimate aim of the interaction between the photographer, the patient and others is to strengthen the self-image of the patient.

Research question: Does the intervention help Ann to accept what has happened to her (having had cancer) and give it a place in her life?

The patient is invited to reflect on how he/she wants to be photographed, where and when. He/she has the direction, though within the boundaries of a dialogue with next of kin, sometimes a buddy and the photographer. The choice how the self-portrait will look like is the result of this dialogue or multilogue. In this way the reflection on ‘how do I want to be photographed?’ does not remain limited to the interaction photographer-patient, but encompasses also the significant others in the direct environment of the patient: family members, may-be caregivers and even fellow patients. When the photographs are ready for showing then again there is this sharing of feelings and thoughts triggered by the image. The photographs picture a story that the patient is stimulated to tell and which is co-created by the response of others (the public of the story).

Research question: Did Ann experience partnership and was the outcome the result of a dialogue/multilogue?

Data collection and analysis

Data were collected from conversations with Ann in which we reflected with her on the process she went through. The interpretation we made were shared among the members of the project(peer review) and put forward to Ann for member check. Supplementary questions were asked at 3 years after she has been photographed, when we were writing this article, we again checked our findings with her and asked her comment.

Case selection

Due to Ann’s initiative in asking the photographer to collaborate, we think this is an example of convenience sampling. As we were still in the phase of having a prototype only and had no formal organisation to back-up our project we were glad to have the opportunity to make a start without too much bureaucratic bother.

The self-selection of Ann means that there was a risk of our findings being biased. But she was also presenting a case that promised rich data, because besides being a patient she was and is also working as a fysiotherapist employed in the same hospital where she had been treated for cancer (Figure 2).

As Stake [9] formulated it:

“The researcher examines various interests in the phenomenon, selecting a case of some typicality, but leaning toward those cases that seem to offer opportunity to learn. My choice would be to examine that case from which we can learn the most [...] Potential for learning is a different and sometimes superior criterion to representativeness.”

Ethical and related issues

No permission from an Institutional Review or Ethical Board was needed to do the case study and publish our findings.

The case report: the story of Ann

Research questions:

-do the photographs facilitate this process of reflection and value finding?

-does the intervention help Ann to accept what has happened to her (having had

cancer) and give it a place in her life?

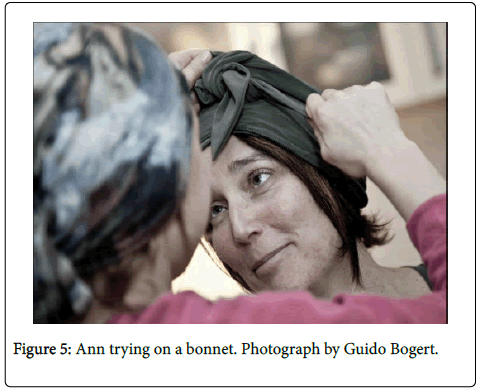

We asked Ann (in several ways and framing it in various different formulations) what the distinguishing aspect was of living with cancer (and beyond), inviting her to show it to us in real life situations. We tried to record these crucial moments in photographs that have punctum (that is: have a stingy aspect about them that makes them linger in the mind and make you wonder what their message is). Often this punctum was found in the changes in how Ann looked at herself and her wondering whether she was still the same person. At her request we focused on the moment of transition when she had her hair shaved, had a wig measured and had to wear a bonnet to hide her bald head.

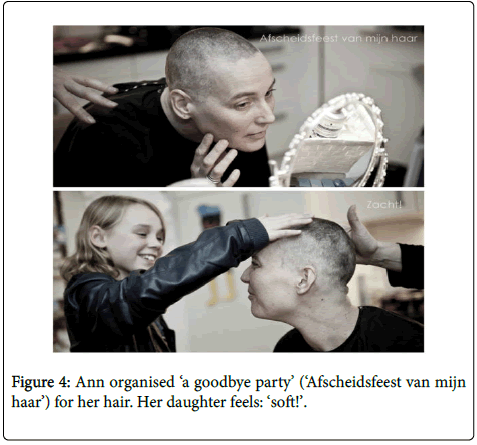

Having a bald head because of the chemo became a point of crystallization that put her self-image acutely in question (Figure 3). Ann was confronted with the question ‘who am I? What makes my life still worth living?’. Looking into a mirror started her off on a trajectory of reconciliating herself with the (self-) image in the pictures and redefining her identity (Figures 4,5).

This was the starting point: the confrontation with the physical and outward consequences of the disease, e.g. the loss of (cranial) hair. Her hair been shaved off, Ann wondered who she really was ‘underneath’. This supported her in becoming aware of what the important, enjoyable and nice things are in her life, besides being a mother. She came up with a creative talent she had: working with textiles and see whether she could design and make ‘comforting cushions’. We accompanied her when she went on a search for suitable textiles and together with her we explored the possibilities of setting herself up in business. We asked students/volunteers from a business school to make a business plan for her. When setting herself up in business seemed not to be feasible she decided to give a course in baby massage and how to use shawls (wraps) in which a baby can be carried. “Take your life in hand again and set goals for yourself. That is what came from the project” (communication by Ann). This involved a form of reminiscing and re-integrating in consciousness of what has been part of her life story may-be for a longer time, but that lay slumbering and was hidden as a dream, a wish or as a talent. Some people (not Ann) need extra imagination exercises here to access these deeper images.

During the trajectory there were 3 photo sessions, which were meant to support the self-expression. They also lend the process momentum. The process of appropriation (re-integrating insight) by the patient of the important things in life is visualized in photographs and therefore more recognizable. The photos and accompanying text showed the kind of person Ann is, the things she likes and the values she believes in. May-be she is a cancer patient in the photograph where she is connected with intravenous lines (Figure 1), but in most of the other photographs she is not a cancer patient, but a person with cancer.

Research question: Did Ann experience partnership and was the outcome the result of a dialogue/multilogue?

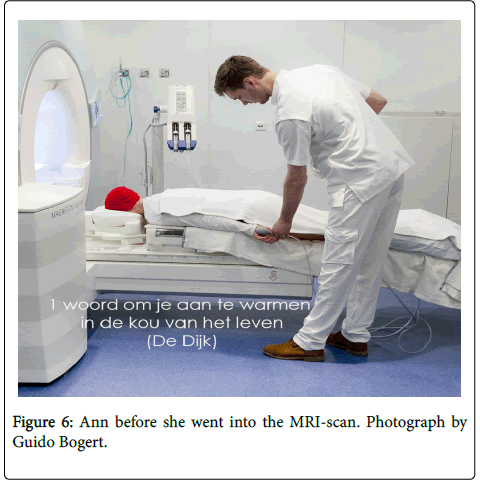

A meaningful encounter between the patient, others (relatives; caregivers) and the photographer took place. The photographer and caregiver were witness to the fact that Ann is more than a patient and consumer of care. Ann emphasized this by giving as comment to the photograph of her lying on a bed just before she will get a MRI-scan (Figure 6): “One word to warm yourself in the cold of life.” Also the acknowledgement by caregivers and relatives of the authenticity of the photo-story is important. Their response to the vulnerable process that Ann went through was of crucial interest. “I experienced that their looking after me was well-meant and that they saw me as patient and a human being. It was not a kind of routine that was performed. They really departed from what I needed.” (Ann).

We know that the support of others is important, when we realize that the reflection and/or re-integration by the patient can be a painful process during which experiences of loss can come to the surface: loss of functionality or of energy to undertake activities, loss of friends and relations or more generally loss of perspective in life and hope. Sometimes this trajectory is too painful to share with others. Still the sharing of experiences and feelings with others can confirm someone that he/she is worthy as a person, even in his vulnerability. In the case of Ann a photo-album facilitated the sharing of feelings and experiences with caregivers, family and important others.

Photography here is at the service of a therapeutic aim: enlargement of self-esteem, the reflection on a valued life and the facing up one’s losses, in order to make better choices how to continue life and be motivated for the (self) management of one’s situation and health condition. The therapeutic working operates upon the interplay of reflection (triggered by photographs), the making visible (palpable and concrete) of what is otherwise often diffuse and difficult to verbalize and the sharing with others (photographs are shown) followed by feedback and response. Looking back on the experience three years later Ann confirmed how she had felt supported at the time.

Discussion

Cancer affects deeply the way how people experience their bodies. When a tumor festers in your body then you become extremely aware of the fact that besides you are a body you also have a body. A body that has betrayed you. There is a war going on inside between the immune system and the cancer cells. The outcome is not sure on beforehand. May-be you are marked by death. May-be you will come out of this struggle as winner. But then you may be battered, for instance when one of the breasts had to be amputated. That part of your body that makes out your feminity has been disfigured, even when breast reconstruction has taken place and plastic surgery. How amputation does affect the self-image? How does it feel to lose your hair in the spur of the ‘struggle’ as the chemo fights the cancer cells? How do you look upon your body when you have become dependent on a stoma due to cancer? For many patients life it will be a matter of life and death. Surviving is the first priority. This will colour everything and also influence how your reactions are on others. However on these moments it is important to keep an eye on the life after and beyond the cancer to retain hope and find strength in it. Otherwise the disease threatens to overwhelm you. Therefore it is important to support the patient in the process of meaning giving. Photography used in an empowering way can do this.

From a literature review by Dwarswaard et al. [12] we know that others are important in the struggle to live a good life with and beyond the disease. A severe disease like cancer is not only an individual experience, but is ‘embedded’ in an environment of the family, the community and larger society, circles that also influence the choices patients (can) make [13]. Fellow patients too are often an important source of support, for instance through the sharing of experiences with the disease (peer contact). In the end the photo portraits and the photo story will make this sharing easier and may render the acknowledgement of its significance into a testimony.

Caregivers can play an instrumental role in facilitating this empowerment, when they realize that partnership is wanted and an attitude of sympathy and commitment. Partnership is in line with the idea of patients participating in treatment matters on an equal footing and caregivers inviting patients to a ‘collaborative’ communication [14] which are mentioned as conditions for a successful self-management in many research findings and policy reports [15]. As yet selfmanagement interventions are too often focused on the individual alone [13]. The act of making photographs is essentially a social event and therefore involves relevant others in the process. The case of Ann demonstrates that there is a need for sharing crucial moments in life and have others testify to you being a valuable person and that this believing in who you are must be made concrete and visible. This confirmed earlier research by Sitvast [5,10,11]. Helping Ann to realize her ambitions was one way to do that and photographing her (when she needed it most) another. The implication for nursing is that nurses must look for creative ways to involve the patient and relevant others in the process of meaning giving as a first step in coping with the disease and its consequences.

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

The pilot testing of the intervention gave us rich data, although this concerns only one patient. Due to self-selection of the participant findings may be biased. The self-directed trajectory is a strong aspect because it put the patient in the lead. At the same time it is a limitation where the patient chose not to explore some topics that might have shone a new light on her role as mother while coping with cancer. We will look into this matter when planning new runs of the interventions. Beside the further development of the intervention new research is necessary, for instance a multi-case study, to understand better how picturizing experiences triggers reflection on deeper felt values and wishes.

Conclusion

Ann showed us that she used the medium of photography to tell her story and found strength in it to go on with her life and find new goals to go for. She used the fact that she was photographed to play with images of herself, showing that she was still the same person. My hair is just hair, she seems to communicate by her photographs, and you can do without it, so why not organise a goodbye party for it and have your new looks admired by your children? The photographs mediated her story where otherwise words alone might not have been able to make sense of confused feelings.

Acknowledgement

I thank members of the project team: Ingrid Bogert and Guido Bogert, who made all photographs. I want to thank Ann, for her openess and her willingness to share her thoughts and feelings with us and I thank the members of the project team: Ingrid Bogert and Guido Bogert, who made all photographs.

References

- Hurk van den CJ, Breed WP, Nortier JW, Coebergh JW (2011) Increase of scalp cooling chemotherapy to prevent hair loss in the Netherlands. Dutch J of Oncol8:256-263.

- Mols F, Van den Hurk CJG, Vingerhoets AJJM, Breed WPM (2010) Scalp cooling to prevent chemotherapy-induced hair loss: Practical and clinical implications. Support Care Cancer 17: 181-189.

- Frith H, Harcourt D (2007) Using photography to capture women’s experiences of chemotherapy: reflecting on the method. Qual Health Res 17: 1340-1350.

- Hagedorn MI (1996) Photography: an aesthetic technique for nursing inquiry. Issues Ment Health Nurs 17:517-527.

- Sitvast J (2014) Hermeneutic Photography. An innovative intervention in psychiatric rehabilitation founded on concepts from Ricoeur. (Turkish) Journal of Psychiatric Nursing 5:17-24

- Ziller KC (1990) Photographing the self. Methods for observing personal orientations.

- Sage Publications. Newbury Park/London/New Delhi.

- Weiser J (1993) Phototherapy Techniques. Exploring the secrets of personal snapshots and family albums.Jossey-Bass Publishers San Francisco.

- Swanborn PG (2010) Case Study Research What, Why and How? Thousand Oaks/London/New Delhi: Sage Publications.

- Stake RE (2001) Case studies. In: NK Denzin, YS Lincoln (eds). Handbook of Qualitative Research (2ndedn.). Thousand Oaks/London/New Delhi: Sage Publications.

- Sitvast J (2008) Photo-stories, Ricoeur and Experiences from practice: a hermeneutic dialogue. ANS AdvNursSci 31:268-279.

- Sitvast J (2013) Self-management and Representation of Reality in Photo-Stories. ANS AdvNursSci 36: 1-15.

- Dwarswaard J, Bakker EJM, Van Staa A, Boeije H (2015) Self-management support from the perspective of patients with a chronic condition: a thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Health Expect 19: 194-208.

- Thirsk LM, Clarke AM (2014) What is the ‘self’ in chronic disease self-management? IntJ of Nurs Stud 51: 691-693.

- Lindenmeyer A, Whitlock S, Sturt J, Griffiths F (2010) Patient engagement with a diabetes self-management intervention. Chronic Illn6: 306-316.

- Van Spil JA, Van Muilekom HAM, Van deWalle-Van de Geijn BFH (2013) Oncology Handbook for nurses and other care providers . Houten ( The Netherlands ) : Bohn Stafleu Van Loghum .

Relevant Topics

- Caregiver Support Programs

- End of Life Care

- End-of-Life Communication

- Ethics in Palliative

- Euthanasia

- Family Caregiver

- Geriatric Care

- Holistic Care

- Home Care

- Hospice Care

- Hospice Palliative Care

- Old Age Care

- Palliative Care

- Palliative Care and Euthanasia

- Palliative Care Drugs

- Palliative Care in Oncology

- Palliative Care Medications

- Palliative Care Nursing

- Palliative Medicare

- Palliative Neurology

- Palliative Oncology

- Palliative Psychology

- Palliative Sedation

- Palliative Surgery

- Palliative Treatment

- Pediatric Palliative Care

- Volunteer Palliative Care

Recommended Journals

- Journal of Cardiac and Pulmonary Rehabilitation

- Journal of Community & Public Health Nursing

- Journal of Community & Public Health Nursing

- Journal of Health Care and Prevention

- Journal of Health Care and Prevention

- Journal of Paediatric Medicine & Surgery

- Journal of Paediatric Medicine & Surgery

- Journal of Pain & Relief

- Palliative Care & Medicine

- Journal of Pain & Relief

- Journal of Pediatric Neurological Disorders

- Neonatal and Pediatric Medicine

- Neonatal and Pediatric Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry: Open Access

- OMICS Journal of Radiology

- The Psychiatrist: Clinical and Therapeutic Journal

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 12930

- [From(publication date):

May-2016 - Aug 29, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 11895

- PDF downloads : 1035